Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Gluten Free Crackers

2.3. Projective Mapping

2.4. Modified Flash Profiling

2.5. Descriptive Analysis

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

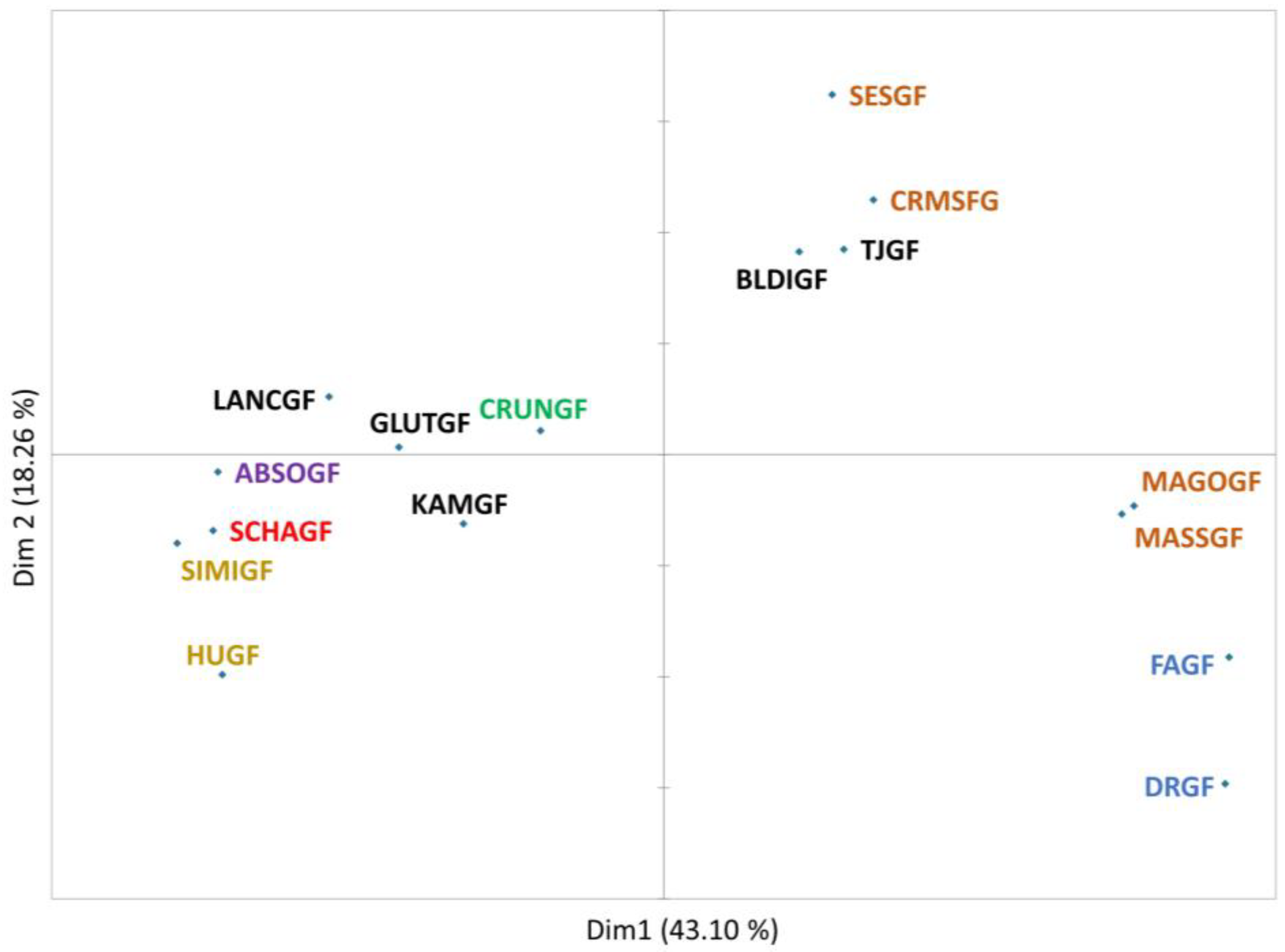

3.1. Projective Mapping

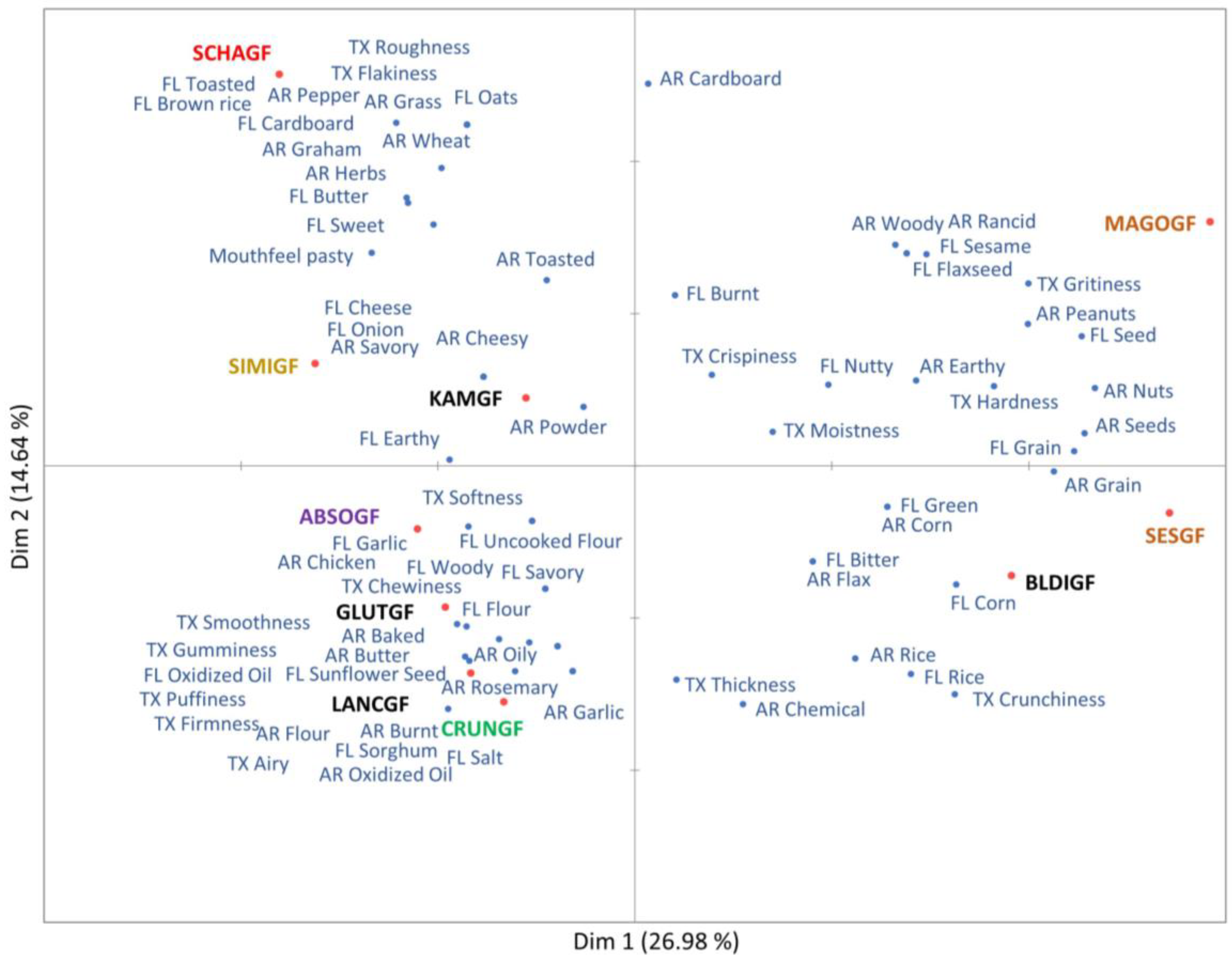

3.2. Modified Flash Profiling

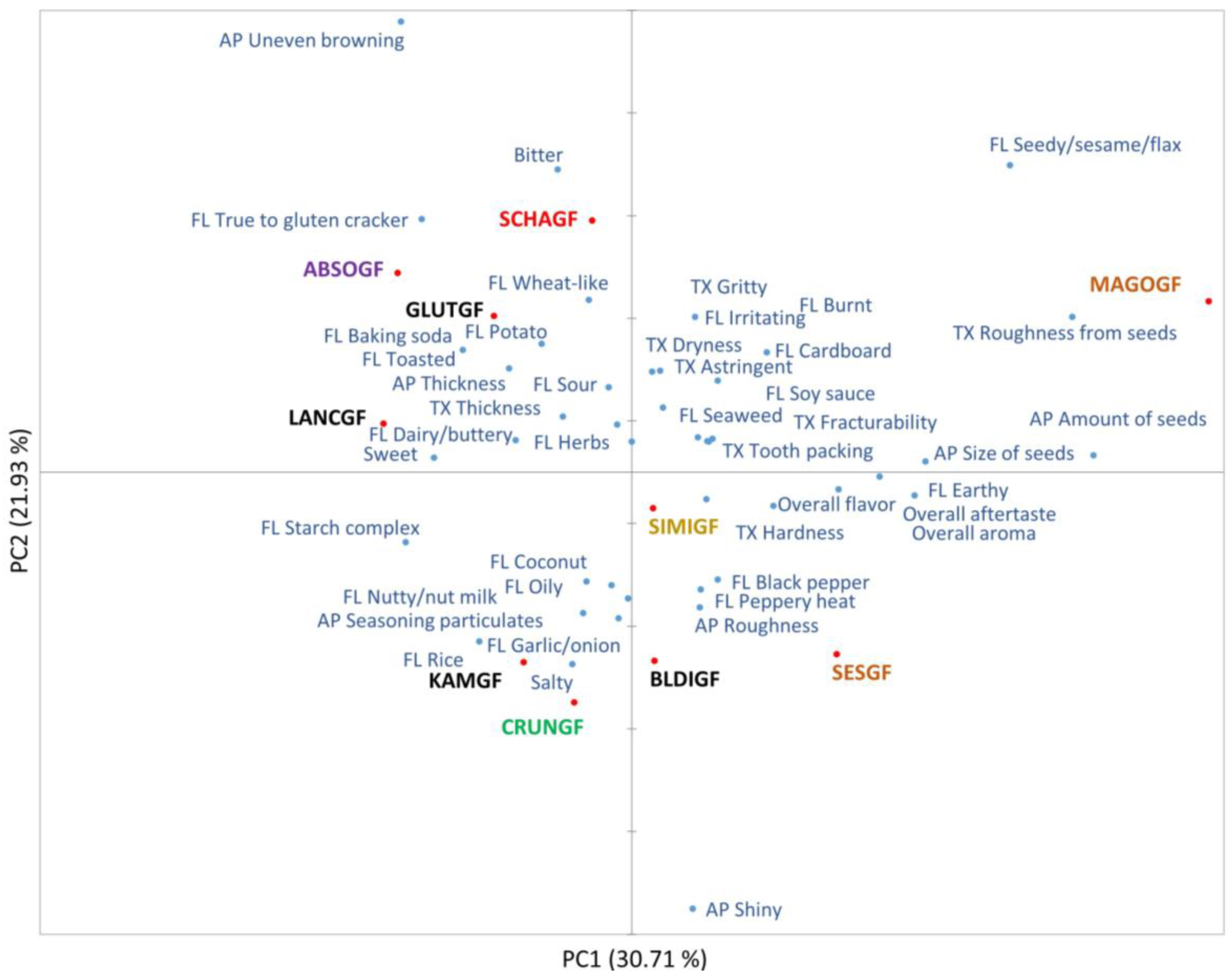

3.3. Descriptive Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Projective Mapping

4.2. Modified Flash Profiling

4.3. Descriptive Analysis

4.4. Comparison Between Modified Flash Profiling and Descriptive Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GF | Gluten free |

| GFC | Gluten free crackers |

| PM | Projective mapping |

| FP | Flash profiling |

| MFP | Modified flash profiling |

| DA | Descriptive analysis |

| MFA | Multiple factor analysis |

| GPA | Generalized procrustes analysis |

| PCA | Principle component analysis |

References

- H. F. Hassan et al., “Perceptions towards gluten free products among consumers: A narrative review,” Applied Food Research, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 100441, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. M. M. Alencar, V. A. de Araújo, L. Faggian, M. B. da Silveira Araújo, and V. D. Capriles, “What about gluten-free products? An insight on celiac consumers’ opinions and expectations,” J Sens Stud, vol. 36, no. 4, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. D. Capriles et al., “Current status and future prospects of sensory and consumer research approaches to gluten-free bakery and pasta products,” Food Research International, vol. 173, p. 113389, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Stantiall and L. Serventi, “Nutritional and sensory challenges of gluten-free bakery products: a review,” Int J Food Sci Nutr, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 427–436, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Mármol-Soler et al., “Gluten-Free Products: Do We Need to Update Our Knowledge?,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 23, p. 3839, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Demirkesen and B. Ozkaya, “Recent strategies for tackling the problems in gluten-free diet and products,” Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 571–597, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. N. Khairuddin and O. Lasekan, “Gluten-Free Cereal Products and Beverages: A Review of Their Health Benefits in the Last Five Years,” Foods, vol. 10, no. 11, p. 2523, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, Y. Zhang, W. Wang, and Y. Li, “Advanced properties of gluten-free cookies, cakes, and crackers: A review,” Trends Food Sci Technol, vol. 103, pp. 200–213, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Bender and R. Schönlechner, “Innovative approaches towards improved gluten-free bread properties,” J Cereal Sci, vol. 91, p. 102904, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. El Khoury, S. Balfour-Ducharme, and I. J. Joye, “A Review on the Gluten-Free Diet: Technological and Nutritional Challenges,” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 10, p. 1410, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- O. Gorach, D. Oksana, and N. Rezvykh, “Innovative Technology for the Production of Gluten-free Food Products of a New Generation,” Curr Nutr Food Sci, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 734–744, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Knežević et al., “Consumer Satisfaction with the Quality and Availability of Gluten-Free Products,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 18, p. 8215, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Fratelli, F. G. Santos, D. G. Muniz, S. Habu, A. R. C. Braga, and V. D. Capriles, “Psyllium Improves the Quality and Shelf Life of Gluten-Free Bread,” Foods, vol. 10, no. 5, p. 954, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Cayres, J. L. Ramírez Ascheri, M. A. Peixoto Gimenes Couto, E. L. Almeida, and L. Melo, “Consumers’ acceptance of optimized gluten-free sorghum-based cakes and their drivers of liking and disliking,” J Cereal Sci, vol. 93, p. 102938, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Di Cairano, N. Condelli, F. Galgano, and M. C. Caruso, “Experimental gluten-free biscuits with underexploited flours versus commercial products: Preference pattern and sensory characterisation by Check All That Apply Questionnaire,” Int J Food Sci Technol, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 1936–1944, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. L. de Kock and N. N. Magano, “Sensory tools for the development of gluten-free bakery foods,” J Cereal Sci, vol. 94, p. 102990, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Roman, M. Belorio, and M. Gomez, “Gluten-Free Breads: The Gap Between Research and Commercial Reality,” Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 690–702, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Tóth, T. Kaszab, and A. Meretei, “Texture profile analysis and sensory evaluation of commercially available gluten-free bread samples,” European Food Research and Technology, vol. 248, no. 6, pp. 1447–1455, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Heberle, B. P. Ávila, L. Á. do Nascimento, and M. A. Gularte, “Consumer perception of breads made with germinated rice flour and its nutritional and technological properties,” Applied Food Research, vol. 2, no. 2, p. 100142, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Laignier et al., “Amorphophallus konjac: Sensory Profile of This Novel Alternative Flour on Gluten-Free Bread,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 1379, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, “The instrumental texture, descriptive sensory profile, and overall consumer acceptance of lentil-enriched crackers,” Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana , 2020. Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scholarworks.montana.edu/handle/1/15891.

- M. Di Cairano, N. Condelli, N. Cela, L. Sportiello, M. C. Caruso, and F. Galgano, “Formulation of gluten-free biscuits with reduced glycaemic index: Focus on in vitro glucose release, physical and sensory properties,” LWT, vol. 154, p. 112654, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Jiamjariyatam, S. Krajangsang, and W. Lorliam, “Effects of Jasmine Rice Flour, Glutinous Rice Flour, and Potato Flour on Gluten-Free Coffee Biscuit Quality,” Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 648–666, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Giménez et al., “Sensory evaluation and acceptability of gluten-free Andean corn spaghetti,” J Sci Food Agric, vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 186–192, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Hosseininejad, V. Larrea, G. Moraga, and I. Hernando, “Evaluation of the Bioactive Compounds, and Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Gluten-Free Muffins Enriched with Persimmon ‘Rojo Brillante’ Flour,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 21, p. 3357, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. de L. de Oliveira et al., “Gluten-Free Sorghum Pasta: Composition and Sensory Evaluation with Different Sorghum Hybrids,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 19, p. 3124, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Esposito et al., “Sensory Evaluation and Consumers’ Acceptance of a Low Glycemic and Gluten-Free Carob-Based Bakery Product,” Foods, vol. 13, no. 17, p. 2815, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Magano, G. du Rand, and H. de Kock, “Perception of Gluten-Free Bread as Influenced by Information and Health and Taste Attitudes of Millennials,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 491, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Ike, “Physicochemical Properties and Rheological Behavior of Gluten-Free Flour Blends for Bakery Products,” Journal of Food Sciences, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 43–55, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Vriesekoop, E. Wright, S. Swinyard, and W. de Koning, “Gluten-free Products in the UK Retail Environment. Availability, Pricing, Consumer Opinions in a Longitudinal Study,” Internatioal Journal of Celiac Disease, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 95–103, 2020.

- W. de Koning et al., “Price, quality, and availability of gluten-free products in Australia and New Zealand – a cross-sectional study,” J R Soc N Z, pp. 1–17, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Xhakollari and M. Canavari, “Celiac and non-celiac consumers’ experiences when purchasing gluten-free products in Italy,” ECONOMIA AGRO-ALIMENTARE, no. 1, pp. 29–48, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Xhakollari, M. Canavari, and M. Osman, “Factors affecting consumers’ adherence to gluten-free diet, a systematic review,” Trends Food Sci Technol, vol. 85, pp. 23–33, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Arslain, C. R. Gustafson, P. Baishya, and D. J. Rose, “Determinants of gluten-free diet adoption among individuals without celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity,” Appetite, vol. 156, p. 104958, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Prada, C. Godinho, D. L. Rodrigues, C. Lopes, and M. V. Garrido, “The impact of a gluten-free claim on the perceived healthfulness, calories, level of processing and expected taste of food products,” Food Qual Prefer, vol. 73, pp. 284–287, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Sielicka-Różyńska, E. Jerzyk, and N. Gluza, “Consumer perception of packaging: An eye-tracking study of gluten-free cookies,” Int J Consum Stud, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 14–27, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Zysk, D. Głąbska, and D. Guzek, “Food Neophobia in Celiac Disease and Other Gluten-Free Diet Individuals,” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 1762, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Paganizza, R. Zanotti, A. D’Odorico, P. Scapolo, and C. Canova, “Is Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet by Adult Patients With Celiac Disease Influenced by Their Knowledge of the Gluten Content of Foods?,” Gastroenterology Nursing, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 55–64, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Vázquez-Polo et al., “Uncovering the Concerns and Needs of Individuals with Celiac Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 17, p. 3681, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Dean et al., “Against the Grain: Consumer’s Purchase Habits and Satisfaction with Gluten-Free Product Offerings in European Food Retail,” Foods, vol. 13, no. 19, p. 3152, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. V. Aguiar et al., “An integrated instrumental and sensory techniques for assessing liking, softness and emotional related of gluten-free bread based on blended rice and bean flour,” Food Research International, vol. 154, p. 110999, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Pinesso Ribeiro, E. A. Esmerino, E. R. Tavares Filho, A. G. Cruz, and T. C. Pimentel, “Unraveling the potential of co-creation on the new food product development: A comprehensive review on why and how listening to consumer voices,” Trends Food Sci Technol, vol. 159, p. 104978, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumar and E. Chambers, “Understanding the terminology for snack foods and their texture by consumers in four languages: A qualitative study,” Foods, vol. 8, no. 10, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Varela and G. Ares, “Sensory profiling, the blurred line between sensory and consumer science. A review of novel methods for product characterization,” Food Research International, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 893–908, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Y. P. Chen, T. K. Chiang, and H. Y. Chung, “Optimization of a headspace solid-phase micro-extraction method to quantify volatile compounds in plain sufu, and application of the method in sample discrimination,” Food Chem, vol. 275, pp. 32–40, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumar, E. Chambers, D. H. Chambers, and J. Lee, “Generating new snack food texture ideas using sensory and consumer research tools: A case study of the Japanese and south Korean snack food markets,” Foods, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1–24, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Kemp, J. Hort, and T. Hollowood, Descriptive Analysis in Sensory Evaluation. Wiley, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Ruiz-Capillas and A. M. Herrero, “Sensory Analysis and Consumer Research in New Product Development,” Foods, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 582, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Marques, E. Correia, L.-T. Dinis, and A. Vilela, “An Overview of Sensory Characterization Techniques: From Classical Descriptive Analysis to the Emergence of Novel Profiling Methods,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 255, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, W. L. P. Bredie, E. Sherman, J. F. Harbertson, and H. Heymann, “Comparison of rapid descriptive sensory methodologies: Free-Choice Profiling, Flash Profile and modified Flash Profile,” Food Research International, vol. 106, pp. 892–900, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. He and H. Y. Chung, “Comparison between quantitative descriptive analysis and flash profile in profiling the sensory properties of commercial red sufu (Chinese fermented soybean curd),” J Sci Food Agric, vol. 99, no. 6, pp. 3024–3033, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Heo, S. J. Lee, J. Oh, M.-R. Kim, and H. S. Kwak, “Comparison of descriptive analysis and flash profile by naïve consumers and experts on commercial milk and yogurt products,” Food Qual Prefer, vol. 110, p. 104946, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Miele, S. Puleo, R. Di Monaco, S. Cavella, and P. Masi, “Sensory profile of protected designation of origin water buffalo ricotta cheese by different sensory methodologies,” J Sens Stud, vol. 36, no. 3, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Dus, L. Stapleton, A. Trail, A. R. Krogmann, and G. V. Civille, “SpectrumTM Method,” in Descriptive Analysis in Sensory Evaluation, Wiley, 2018, pp. 319–353. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Hootman, “Manual on descriptive analysis testing for sensory evaluation,” Philadelphia: ASTM, 1992.

- B. J. Plattner et al., “Use of Pea Proteins in High-Moisture Meat Analogs: Physicochemical Properties of Raw Formulations and Their Texturization Using Extrusion,” Foods, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 1195, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Society of Sensory Professionals (SSP), “Recommendations for Publications Containing Sensory Data,” Available online. Accessed: Jun. 05, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sensorysociety.org/knowledge/Pages/Sensory-Data-Publications.aspx.

- G. T. de Castro et al., “Evaluation of the substitution of common flours for gluten-free flours in cookies,” J Food Process Preserv, vol. 46, no. 2, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Giuberti, G. Rocchetti, S. Sigolo, P. Fortunati, L. Lucini, and A. Gallo, “Exploitation of alfalfa seed (Medicago sativa L.) flour into gluten-free rice cookies: Nutritional, antioxidant and quality characteristics,” Food Chem, vol. 239, pp. 679–687, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Ribeiro, M. Magnani, T. R. Baú, E. A. Esmerino, A. G. Cruz, and T. C. Pimentel, “Update on emerging sensory methodologies applied to investigating dairy products,” Curr Opin Food Sci, vol. 56, p. 101135, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Moss and M. B. McSweeney, “Projective mapping as a versatile sensory profiling tool: A review of recent studies on different food products,” J Sens Stud, vol. 37, no. 3, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Cracker brand | Code | Flour base | Ingredients | Variety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolutely gluten-Free crackers* | ABSOGF | Tapioca/potato starch blend | Tapioca starch, water, potato starch, potato flakes, palm oil, honey, egg yolks, natural vinegar, salt | Original |

| Crunch Master grain free crackers* | CRUNGF | Cassava flour | Cassava flour, organic coconut flour, tapioca starch, safflower oil, sea salt, garlic powder | Original |

| Hu Gluten-Free Grain-Free Crackers | HUGF | Almond, Cassava, Coconut flour blend | Grain-free flour blend (almond, cassava, organic coconut), black chia seed, flax seed, organic coconut aminos | Sea Salt |

| Schar Table gluten-free crackers* | SCHAGF | Millet blend | Non GMO corn starch, vegetable fats and oils (palm, palm kernel, non GMO rape seed), maltodextrin, modified tapioca starch, whole millet flour, non GMO soy flour, rice syrup, whole rice flour, buckwheat flour, sorghum flour, flax seed flour, non GMO corn flour, dried sourdough (buckwheat, quinoa), non GMO soy bran, poppy seeds, non GMO sugar beet syrup, sea salt, cream of tartar, ammonium bicarbonate, baking powder, guar gum, modified cellulose, citric acid, natural flavoring (rosemary) | Original |

| Simple Mills Sea salt crackers* | SIMIGF | Nut flour blend | Nut and seed flour blend (almond flour, sunflower seeds, flax seeds), tapioca starch, cassava, organic sunflower oil, sea salt, organic onion, organic garlic, rosemary extract (for freshness) | Sea Salt |

| Glutino gluten-free crackers* | GLUTGF | White rice | Corn starch, white rice flour, organic palm oil, modified corn starch, eggs, sugar, salt, vegetable fibers, dextrose, guar gum, sodium bicarbonate, natural flavor, monocalcium phosphate, ammonium bicarbonate | Original |

| Blue Diamond nut Thins* | BLDIGF | White rice | Rice flour, almonds, potato starch, sea salt, safflower oil, natural flavors (contains milk) | Original |

| Lance gluten-free crackers* | LANCGF | White rice | Palm oil, rice flour, rice starch, sugar, corn starch, potato starch, baking soda, tapioca flour, glucose, xanthan gum, monocalcium phosphate, salt, soy lecithin, locust bean gum, non-fat milk | Original |

| Trader Joe’s Savory Thin Crackers | TJGF | White Rice | Rice, sesame seeds, expeller pressed safflower oil, tamari soy sauce (soybeans, rice, salt), salt, garlic, soybean | Original |

| Mary’s Gone crackers* | MAGOGF | Brown rice | Brown rice, quinoa, flax seeds, sesame seeds, tamari (water, soybeans, salt, vinegar), sea salt | Original |

| Sesmark gluten-free crackers* | SESGF | Brown rice | Rice flour, expeller pressed safflower oil, sesame seeds, sesame flour, wheat free tamari soy sauce powder [tamari soy sauce (soybeans, salt), maltodextrin (from corn)], wheat free teriyaki powder, [wheat free teriyaki sauce (tamari soy sauce ([soybeans, salt),], sake (rice, salt), apple cider vinegar, garlic, mustard, ginger, white and black pepper), maltodextrin, sucrose, fructose,], onion powder and soy lecithin | Sea Salt |

| Mary’s Gone Super Seed Gluten -Free Crackers | MASSGF | Brown Rice | Brown rice, quinoa, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, flax seeds, sesame seeds, poppy seeds, sea salt, seaweed, black pepper, spices | Original |

| Crunch Master Multigrain Crackers | CRMSGF | Brown Rice | Brown rice flour, whole grain yellow corn, potato starch, safflower oil, oat fiber, cane sugar, sesame seeds, flax seeds, millet, sea salt, quinoa seeds. | Original |

| Ka Me rice crackers* | KAMGF | Jasmine rice | Jasmine rice, rice bran oil, sea salt, soybean tocopherols (preservative) | Original |

| Doctor in the Kitchen Flackers | DRGF | Flaxseed | Organic flax seeds, organic apple cider vinegar, sea salt | Sea Salt |

| Foods Alive Original Flax Crackers | FAGF | Flaxseed | Golden flaxseed, bragg liquid aminos (a non-GMO wheat-free soy sauce), lemon juice | Original |

| Appearance | Aroma and flavor | Texture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified flash profiling | Descriptive | Modified flash profiling | Descriptive | Modified flash profiling | Descriptive | |

| Aroma | Flavor | Aroma and flavor | ||||

| None | Amt of seeds/inclusions | Baked | Bitter | Astringent | Airy | Dryness/moisture absorbency* |

| Color | Burnt | Brown rice | Baking soda | Chewiness | Fracturability | |

| Holes (yes/no) | Butter | Burnt | Bitter* | Crispiness | Grit/chalky/mouth coating* | |

| Rough appearance | Cardboard | Butter | Black pepper* | Crunchiness | Hardness* | |

| Seasoning particulates | Cheesy | Cardboard | Burning heat from pepper | Firmness | Roughness(seeds/particulates)* | |

| Shape | Chemical | Cheese | Burnt* | Flakiness | Thickness* | |

| Shiny | Chicken | Corn | Cardboard* | Grittiness | Tooth stick/tooth packing | |

| Size of seeds | Corn | Earthy | Coconut (flour) | Gumminess | ||

| Thickness appearance | Earthy | Flaxseed | Dairy/buttery* | Hardness | ||

| Uneven browning | Flaxseed | Flour | Earthy* | Moistness | ||

| Flour | Garlic | Garlic/onion* | Puffiness | |||

| Garlic | Grain | Herbs* | Roughness | |||

| Graham | Green | Irritating | Smoothness | |||

| Grain | Nutty | Nutty/nut milk* | Softness | |||

| Grass | Oats | Oily* | Thickness | |||

| Herbs | Onion | Overall aftertaste | ||||

| Nuts | Oxidized oil | Overall aroma | ||||

| Oily | Rice | Overall flavor | ||||

| Oxidized oil | Salt | Potato (flour, starch) | ||||

| Peanuts | Savory | Rice (flour, starch)* | ||||

| Pepper | Seed | Salty* | ||||

| Powder | Sesame | Seaweed | ||||

| Rancid | Sorghum | Seedy/sesame/flax* | ||||

| Rice | Sunflower seed | Sour | ||||

| Rosemary | Sweet | Soy sauce | ||||

| Savory | Toasted | Starch complex | ||||

| Seeds | Uncooked flour | Sweet* | ||||

| Toasted | Woody | Toasted* | ||||

| Wheat | True to gluten cracker | |||||

| Woody | Wheat-like* | |||||

| Modified flash profiling | Descriptive analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of products evaluated | 10 | 10 |

| Number of panelists | 18 | 5 |

| Number of sessions | 3 | 3 |

| Panel type | Untrained (individual evaluations) | Trained (consensus) |

| Task | Used own words to describe the attributes. Rate products’ perceived attributes for intensities | Rate products for intensities. Panelists were trained on specific attributes and references |

| Scale used | 4-point scale (0 = none, 1 = low, 2 = medium, and 3 = high) | 150-point scale with 1.0 increments |

| Data analysis type | Multiple factor analysis | Principle component Analysis |

| Total number of attributes | 74 | 44 |

| Appearance | - | 7 |

| Aroma | 30 | - |

| Flavor | 28 | 30 |

| Texture | 15 | 7 |

| Mouthfeel | 1 | - |

| Results | Global overview of commercial gluten free crackers space. Ideal for obtaining consumer differentiation. | Precise, accurate, and consistent measurements between cracker samples. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).