1. Introduction

In October 2014, Indian newspapers and world news reported on a story about the arrest of a man charged by his wife under Section 377 in the Indian Penal Code (IPC), a colonial-era anti-sodomy law [

1]. The two had been married for several months but had never been physically intimate. After being informed by neighbors that the husband was having a male guest over in her absence while she was working at a professional job, the wife installed cameras in their home. The cameras captured footage of her husband having sexual encounters with a man. Hoping to end the marriage and preserve her reputation, the wife presented the recorded evidence to the police. According to IPC law at the time, the husband faced ten years to life in prison. In the first breaking stories of the newspaper, the distressed wife was quoted in the papers lamenting that her life had been ruined and described her husband’s ritual of applying make-up and lip gloss every day. Initial print coverage revealed too much detailed information, enabling the possibility of identification and social repercussions for the couple, followed by calls for retractions by journalists and activists. The story disappeared after 2016.

This news story provides a canvas with which to compare frames of misogyny and homophobia and includes important features of the personal economic balance in the home. How did the combination of gendered social practices and relations, what Connell refers to as the gender order [

2], culminate in the unfortunate domestic union and subsequent parting of two people who knew so little about each other? Norms about maintaining silence on matters of sexuality, gender, and relationship alternatives foreclose the communication that might have prevented this scenario. Furthermore, far from concerning a minority, as stated by the Indian Supreme Court in 2013, anti-sodomy laws such as Section 377, which concern otherwise consensual sex, reflect a long history of social control that implicitly regulates

all forms of relationships, sexuality, and gender relations. What can we learn from the histories and hierarchies behind these norms and laws? The events leading up to this arrest provide an entry point into the complex and changing relations of gender and sexuality in contemporary middle class, urban India.

Heteropatriarchy is a social construct of power that rationalizes the subjugation of women and queer (people with alternative sexual orientation and gender identities, sometimes known as SOGI). Claims of “natural order” or “god-given” authority establish the norm of the privilege of cis, heterosexual men at the top of the hierarchy [

3]. This research draws from interviews middle class Delhi; in which women, men, heterosexuals, and queer people discuss how and where they obtain information on gender and sexuality norms and situates them in the context of scholarship that considers social, political, and economic histories of the region. Interview data is then triangulated with ethnographic participation in Delhi-based events that examine and confront aspects of heteropatriarchal regulation of gender and sexuality. Interview respondents consistently noted marked taboos around discussing sexuality and questioning sexuality and gender norms. How do taboos reinforce socially constructed, institutionalized norms that broadly affect the attitudes and experiences of all people? How do modern institutions of heteropatriarchy reproduce and naturalize both homophobia and the limited autonomy of women? From what positions are people examining, resisting, and reimagining existing gender and sexuality norms?

Publicly contested norms and changing laws regarding gender and sexuality are of interest in India, and on a global level. In these specifically located movements, lives, and conversations we can begin to identify the effect of patriarchal, colonial, and neoliberal constructions of what is considered normal [4-6]. The collusion and pressures of local patriarchies, colonialism, nationalism, and liberalizing markets contributed to foreclosures and regulations of intimacy, family, and kinship forms [7-11]. This scholarship contradicts assertions that queerness- alternatives to binary gender norms and heterosexuality are recent Western phenomena imposed upon essentially traditional Indian cultures.

At the heart of this investigation are the intersecting and conflicting interests of women, men, transgender, heterosexual, and queer people regarding their autonomy, recognition, and rights. The theoretical aim of this paper is to consider present-day implications of historical, social, and legally enforced binary gender and sexuality norms concerning taboos and economic viability. Beginning with current events, it examines how recent applications of the Indian Penal Code bring conflicting questions regarding sexuality and gender to the fore. After a discussion of ethnographic and interview methods, the paper focuses upon themes that emerge from the data over four years of interviews in Delhi and examines the paradoxical roles of taboo regarding heteropatriarchy. The paper closes by conceptualizing these intersections and tensions for women, men, and queer people as they attempt to move toward social equality. The binary construction of gender among the middle class emerges as a defining or primal hierarchy. This primal hierarchy then intersects with other social hierarchies, particularly with economic autonomy.

1.1. Social Context Through Pertinent Judicial and Legislative Background 2009-2015

This research was conducted during a time of significant transformation in the laws, practices, and politics of gender and sexuality in India. Several notable and highly publicized judicial proceedings provide insight into these central fault lines and fissures. They are presented here in chronological order.

In the

NAZ judgment, of July 2009, the Delhi High Court passed a verdict that read down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), declaring it unconstitutional in a judgment hereafter referred to as NAZ [

12]. Section 377 is the 1860 British colonial-era anti-sodomy law that regulates sexual practices between otherwise consenting people having “carnal intercourse against the order of nature”. Though not explicitly naming homosexuality, and even though several of the acts referred to are practiced by some heterosexual persons, Section 377 IPC has been broadly interpreted to implicate men who have sex with men (MSM) and has provided leverage to harass, extort, and threaten MSM and transgender people [

12,

13]. The queer and feminist activists who formed coalitions to defeat 377 celebrated this landmark decision even while keenly aware that NAZ did not confer acceptance of alternative sexualities and families, merely a decriminalization of several specific consensual sexual behaviors.

In the

Koushal judgment In December 2013, the NAZ decision by the Delhi High Court reading down Section 377 was overturned by a two Justice supreme-court decision referred to as Koushal, which essentially reinstated the colonial sodomy law in an unexpected reversal [

14]. Protests and vigils arose across the nation and drew pledges of support from civil society around the globe. This immediately resulted in widely publicized citywide and nationwide gatherings of the interested public, activists, scholars, and advocates to strategize, organize, and push back against what was largely seen as a betrayal of the human rights of Indian citizens.

The Justice

Verma Commission was formed almost immediately after a December 2012 widely publicized violent gang rape [

15]. People were shocked and angered by the violent and ultimately fatal gang rape of a young woman student who was traveling home on a bus in the evening after seeing a film with a male friend. Spontaneous protests arose across the nation against police inaction and rapist impunity, slow-moving courts, and a culture of disrespect toward women. In a move of unprecedented promptness by the government, the Verma Commission sought input and made draft recommendations for additional changes to the IPC rape and sexual assault/sexual harassment laws, as well as input for related social policy. It is the most recent iteration of engagement with sections 375 and 376 IPC, about rape. Activists from many longstanding feminist movements have produced scholarship and modeled resistance to the implications of patriarchal structures and violence against women since before Independence [

16,

17,

18]. Sites of these resistances range from spontaneous uprisings to informal collectives such as Saheli in New Delhi, to NGOs concerned with gender, education, and intimate violence.

The resulting 2013 report from the Verma Commission was well-received and widely hailed by feminist and social justice activists as a comprehensive and thoughtful document. It calls to end the culture of “honour”, purity, and shame, to discontinue exceptions for marital rape, to end impunity to armed forces in conflict regions, and to immediately institute comprehensive sexuality education for young people, and other measures [

19]. To this date, only a few of the recommendations have been implemented, none of the above issues have been addressed, and the reforms that have been taken up notably leave out the recognition of marital rape as a crime or acknowledge that it even occurs [

19]. This omission has been decried by activists, scholars, and advocates alike. A telling passage from the Criminal Law Amendment Act 2013 illustrates some of the thinking behind the opposition to recognizing marital rape as a punishable crime [

20]:

Some members also suggested that somewhere there should be some room for a wife to take up the issue of marital rape. Consent in marriage cannot be consent forever. However, several members felt that the marital rape has the potential of destroying the institution of marriage. The committee felt that if a woman is aggrieved by the acts of her husband, there are other means of approaching the court. In India, the family system has evolved and is moving forward. Family can resolve the problems, and there is also a provision under the law for cruelty against women. It was, therefore, felt that if marital rape is brought under the law, the entire family system will be under great stress, and the committee may perhaps be doing more injustice. [

20] (p. 47)

In the

NALSA judgment of April 2014, the Supreme Court rendered a historic judgment recognizing the third-gender status and human rights of transgender persons in a largely unexpected decision- referred to as NALSA (The National Legal Services Authority, India) [

21]. This unprecedented judgment was written not even five months after Koushal and the reinstatement of section 377. On April 15, 2014, a different constellation of the Indian Supreme Court essentially acknowledged the existence of non-binary conforming gender identities, including transgender people, and proposed measures to begin addressing the widespread societal discrimination they face [

22]. This is significant in its difference from binary constructions of transgender from a Western construction of people transitioning from one gender to the other as in Female to Male (FTM) or Male to Female (MTF) and instead creates an unprecedented legal identity for a third (and possibly more) gender categories, the existence of which are not [yet] intelligible in American or European civil or legal society [

22,

23].

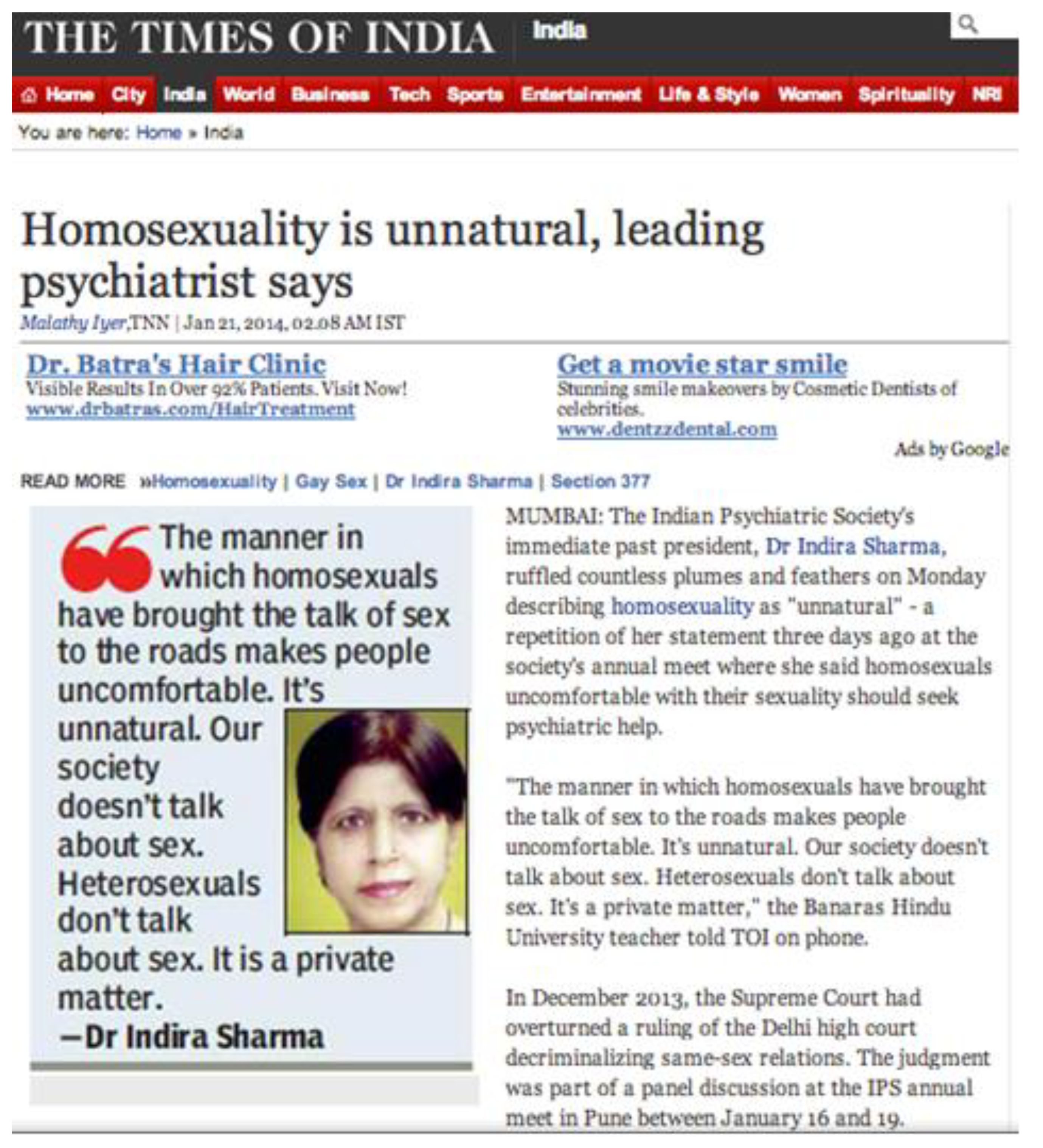

NAZ, Koushal, NALSA, and the anti-rape laws, commission report, and amendments left people in 2015 with several sets of contradictions that move beyond abstract considerations and profoundly affect people’s lives. Examining these judgments and their precipitating events reveals an interplay of shared concerns regarding people’s claims to well-being, equal opportunity, autonomy, human rights, and bodily dignity. These sections of the IPC and the judgments, amendments, and cases mentioned above relate to gender identities and sexual acts that underscore tensions between what is considered acceptable versus normative or natural and what is considered consensual versus coercive. The first significant contradiction lies in some of the most widespread effects of these court actions: they provoke detailed, explicit, public discussions about gender and sexuality. These uncomfortable dialogs are not conducive to tolerance or problem-solving and can heighten conflict or denial in a social atmosphere of rigid taboos. [see appendix A as an example in the print media]. Other emergent contradictions will be discussed later.

1.2. Conceptual Frameworks: Connell’s Gender Order, Heteropatriarchy and Taboo

Recent judicial decisions and the Verma Commission confront historically situated perspectives of gender orders and norms. Raewyn Connell provides a theoretical perspective on gender that moves beyond discursive constructions informed by Butler and Foucault [

7,

24]. She outlines a materially based perspective that includes the colonial and global economic processes imposed upon the local communities and then hybridized with local elite gender orders. Connell describes gender order as a complex relation, focusing on the lived material conditions that weave throughout and partially constitute power relations between individuals and institutions in each society at a given time. Connell draws attention to the changing nature of gender orders over time and the focal possibilities of change within specific social institutions such as families, governments, and organizations [

2].

Connell’s framework of gender is augmented with an analysis of the concept of heteronormativity and heteropatriarchy and their associated hegemonic politics and power engaged by many South Asian and other scholars such as Menon, Narrain & Bhan, Sharma, and Vanita [10, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. Building upon the scholarship of Judith Butler’s “heterosexual matrix” [

30], Narrain asserts that heteronormativity can be defined as “the primacy of heterosexuality that has been coded into societal institutions in a way that heterosexuality appears natural” [

31]. The concept constructs heterosexuality as

the only natural possibility, and all other sexual ways as

unnatural. This dichotomy plays a significant role in the justification of the colonial anti-sodomy law. Saskia Wieringa describes heteronormativity alternatively as “regulating the moral codification of sexuality. The heterosexual family is a central site for the production of sexuality, of its pleasures, but also for the policing of counter-normative desires, deemed dangerous to the stability of the patriarchal order” [

28] (p. 9). Nivedita Menon elaborates on this order, linking it to property, family, and citizenship:

"The family...in the only form in which it is allowed to exist in most parts of the world- the heterosexual patriarchal family- is the key to maintaining social stability, property relations, nation, and community. Caste, race, and community identity are produced through birth. But so too in most cases, is the quintessential modern identity of citizenship. The purity of these identities, of these social formations, and the existing regime of property relations is thus dependent on a particular form of the family." [

10] (p. 30)

Intertwined with structures of Connell’s gender orders and hierarchies, heteronormativity provides a lens to envision and question the persistence and ubiquity of certain relationships and family forms above others. Feminist and Queer scholarships investigate inequalities and power and interrogate the naturalizing and regulation of binary categories in which male and female are essentialized in mutually exclusive normative roles [

32]. In other words, these investigations provide the language and methodology with which to question fixed, immutable categories such as woman and man, along with the power hierarchies ascribed to such identities. Adding Connell’s relational gender theory, heteronormativity adds a relational framework to the intersections of race, class, caste, gender, and ability.

During the research, the concept of taboo emerged from a grounded theory process as a unifying theme for understanding the barriers and environments in which people obtain information and communicate about gender and sexuality. Concepts of taboo provide useful focal points indicating areas of tension around the power status quo. The social power of taboo is articulated by the anthropologist Mary Douglas:

"...taboo as a spontaneous device for protecting the distinctive categories of the universe. Taboo protects the local consensus on how the world is organized. It shores up wavering certainty. It reduces intellectual and social disorder. Ambiguous things can seem very threatening. Taboo confronts the ambiguous…" [

33] (p. xi)

Linguists Allan and Burridge assert that taboos arise out of social constraints on an individual’s behavior in specific societies at singular places and times [

34] (p. 27). Affirming the role of taboo in maintaining power, linguists Allan and Burridge write that in the English-speaking world, some of the earliest censoring and taboos involved “suppressing heresy and speech that was likely to stir up political revolt” [

34] (p. 13). Only later, in the 16th Century did taboo begin to concern patterns of sexuality that could be construed as “subversive of the common good” [

34] (p. 13). They claim that “In most cultures, the strongest taboos are against non-procreative sex and sexual intercourse outside the family unit sanctioned by religion, love or legislation” [

34] (p. 145).

As taboos obscuring issues around sexuality and gender become contested in public, paradoxes and contradictions of social categories and behaviors are revealed. Paradox is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as a statement or proposition that, despite sound (or apparently sound) reasoning from acceptable premises, leads to a conclusion that seems senseless, logically unacceptable, OR a seemingly absurd or self-contradictory statement or proposition that when investigated or explained may prove to be well founded or true, OR a situation, person, or thing that combines contradictory features or qualities. Several emergent paradoxes regarding taboos on the discussion of sexuality and gender alternatives are discussed in the conclusion.

1.3. Historical Erasures: Antiquity, Colonialism, Nationalism, and the Economy

In keeping with Connell’s historical and material grounding of gender order and alternative sexuality forms, close examination reveals a wide diversity of practices and relations in India. Much of this diversity has been erased during times of significant social and cultural changes over the centuries. The landscapes of kinship, gender, and sexuality in India before colonialization and nation formation were particularly diverse from region to region resulting from settlements, migrations, and incursions of different groups over thousands of years. While scholars caution not to assume a golden age of progressive pre-colonial gender relations [

35], never-the-less, sociologists, anthropologists, and demographers have documented a diverse range of forms of family and kinship arrangements, some persisting even to the present day [

36,

37]. Regarding sexualities, historians have excavated and elevated same-sex love and sensibilities from epic narratives and poetry from Hindu, Muslim, and other peoples [

35], and social scientists [

36,

38] have examined gender variations implicated in alternative kinship systems. Scholars have also worked together with documentarians to capture long-lost same-sex lovers in art and architecture- see the Film “No Easy Walk to Freedom” [

39]. Aside from variations over time, regional gender variations in lineage, household formation, and property ownership have persisted and spread to other areas. Of note are the well-documented trends toward patrilineal families [

40] in northern regions, versus different types of matrilineal arrangements in the south and northeast areas [17, 41] and cross-cousin marriages in the south [

36]. In addition, alternative living arrangements in families sometimes involve people of differing gender constructions such as Devadasis [

37] and hijras [

38].

Contact with foreign peoples, invasions, trading relationships, and the colonial period ushered in rapid changes and cultural ruptures on the Indian subcontinent. Connell, Lugones, and Mies map out scholarship regarding the coloniality of gender, examining the ways that colonial frameworks of power and gender threw existing gender relations into disarray and subsequently unmade and remade the gender relations they encountered through violence, legislation, and collusion [ 2, 42, 43]. To have a better understanding of the political and economic gender perspectives imposed by colonization, it is necessary to consider the forces that were operating at the time of the growth of the Indo-European trading routes and the eras that followed.

Scholarship that examines significant changes in the gender order of European societies before the colonial period provides important insight into the origins of some of the erasures, taboos, and criminalization that subsequently affected Indian societies. Federici, Ehrenreich, English, and Mies assert that the sweeping changes in property ownership, production, sexual division of labor, and the rising institutionalization of medicine, law, education, and religion in Europe were centrally implicated in the centuries of systemic, violent persecution of women [43, 44, 45]. In European witch trials and executions, as many as 500,000

or more people were killed within their communities over roughly 300 years, with no recourse to appeal [

46]. Simultaneously, as people were displaced from land to labor in extractive industries and factories, people migrated, and extended communities and families were fractured. Women and men were increasingly tied into small domestic units in which women performed most of the care work that enabled laborers and reproduced the system. The violent appropriation and sequestration of women’s reproductive and care work into patriarchal family forms facilitated the emerging systems of production and wealth accumulation in what soon became aggressive economic empires. Gender norms regarding women moved into a position beyond question as part of the socially constructed “god-given” or “natural order” that privileged the growth of the capital-oriented market system.

Subsequently, the colonizers’ concerns with gender and sexuality in India came to include enforcing the hierarchal, binary gender norms, as well as maintaining boundaries of race, class, nationality, and the orderly accumulation and dispersal of property [10, 47]. Hegemonic masculinities of the elite defined the secondary masculinities of colonial subjects and their complimentary respectable femininities, all reinforcing notions of heteropatriarchy so that these categories became solidified and naturalized in the modern subject. Historians of the region have unearthed legacies of alternative accountings of lineage and women’s agency before and during the colonial period, which have complicated and enriched the narrative [

48,

49]. Indeed, the fact that they have had to be unearthed emphasizes their erasure.

Historians, demographers, and anthropologists have documented broad diversity in gender forms, sexual bonds, and kinship ties involving men, women, and transgender people in non-heteropatriarchal roles, relationships, and families. Yet these diversities are marginalized by economic and legal invisibility. Often, alternative kinship arrangements have been prohibited by a combination of colonial and national legal foreclosures and altered by the subsequent dwindling of economic channels by outlawing unrecognized livelihoods and patterns of inheritance. For example, Ramberg [

37,

50] documents how Devadasis, daughters dedicated to a goddess, can function economically as sons, interacting across castes and enhancing the status and wealth of their natal families. This contrasts with undedicated daughters, who, through marriages with men, transfer wealth and value to their husbands’ families. With colonization, modernity, and globalization, decades of reforms have reduced the nuanced roles and reciprocities that have long benefitted local families in symbolic and material ways. These women, who have served in the past as conduits for beneficial flows of energy and economy, are now often misread out of context as trafficked women or prostitutes. The state has not only criminalized the further dedication of daughters but financially rewarded men who marry and confer so-called “legitimacy” to women who were once dedicated. In another case of gender variation and colonial intervention, traditional

hijra households are not legally recognized, and therefore,

hijras themselves cannot legally inherit property [

38]. These practices are examples of how the state and laws regarding property prevent people from being able to reproduce social arrangements that have been traditional and sustainable in their own lives and contexts. Many of the forms of gender, kinship, and sexuality that were non-normative, and unintelligible within the economic processes erected primarily between and among elite men, were forced underground, forbidden, and finally rendered nearly invisible and forgotten [9, 17, 36, 37, 48, 49, 51].

Colonial instigations of changes in gender structures later segued into projects of independence from British rule and the formation of the Indian Nation. The so-called “civilizing mission” of the colonizers colluded with elite Brahmanical forms of patriarchy that regulated women’s sexuality and kept castes separate and inheritance legible along patrilineal patriarchal forms. As centralized forms of trade and market rolled out, separate spheres of public and private further pushed elite and highly educated women into the home, and they became the feminine models for the new nation’s “forward” movement [

47].

In the decades after independence, feminist scholars in South Asia examined the material conditions and constraints of women’s participation in economic and civic life, documenting the often-unacknowledged work that women, particularly poor women, undertook in their everyday lives. Jain & Banerjee, Kumar, and Nair & John draw links between economic practices, gendered divisions of labor, and family forms throughout history [9, 16, 52]. Inheritance, marriage, and family legislative acts, while striving for and failing to achieve uniformity, have also created ruptures and fed contention, exacerbating what may have been minor or tolerable differences between religious or communal groups. This further forecloses local variations in family and inheritance patterns so that some are preserved and codified, while other alternatives are lost to intelligibility even as their languages and possibilities are lost and forgotten.

More recently, in processes that echoed those of colonialism, amidst international pressures and alliances, another critical period began with the 1991 liberalization of India when the economy and the media opened to Western market engagements and cultural products. Despite being hailed by some as an unquestioned boon to a growing middle class, a boost for the empowerment of women, and a triumph of liberal values, scholars have noted that market liberalization has also created or re-enforced hierarchal gender norms by promoting consumerism and increasing insecurity and inequality [53.54,55,56]. Economic liberalization has both broadened and burdened the middle class, and it is often experienced vastly differently by middle class women and men as women move into marginal work, and according to Phadke & Misra, as semi-public spaces such as shopping malls draw them in as consumers [

57]. Meanwhile, queer and transgender people continue to be marginalized and barely visible in the world of markets, hetero-patriarchal gender norms, and criminalized sexuality. However, it is not premature to predict aggressive marketing efforts directed toward these same groups in the immediate future.

1.4. Development and Human Rights: Diversity Lost in Translation

Moving from erasures related to colonial, national, and market forces, the transnational development language of subjects with human rights still fails to include the diverse experiences of gender, kinship, and sexuality. Jolly, Khanna, Lind, and Sharma write about heteronormativity in development work and provide a relevant critique from within development scholarship [

25,

58,

59]. They point out that other forms of family and relationships have often been unintelligible to practitioners outside of the local contexts, echoing the erasures of colonialism. The importation of frameworks such as human rights in development work often, unfortunately, overlooks or supplants local variations and understandings of sexuality and gender norms. In this way, development work around sexuality has too often been blind to gendered practices on the ground except for how they relate to projects of public health or population [

60]. This is not to dismiss the vital importance of human rights frameworks in aiding women’s or queer people’s efforts to lift themselves from subordination. However, the framing of development work relating to gender can, unfortunately, reify socially constructed essential male/female binary, yet again foreclosing possibilities for individuals and groups they seek to serve. For example, when Jolly asks “Why is development work so straight?” she points out that female-headed household (FHH) is a category used only to signify the absence of an adult male as a head of household, and that these households are often considered at risk and seen as vulnerable according to development indices [

25]. The possibility that FHH households could be matrilineal, extended, lesbian, or otherwise purposefully headed by a woman, with or without adult men present, is not even considered!

Sharma explores how the conventions of heteronormativity are sometimes strategically deployed, and that the negotiation of norms is a process, not a binary overturning of norms for the previously non-normative [

27]. She further interrogates the primacy of romantic love over the bonds of friendship, a significant but often invisible basis of survival and kinship and often overlooked even in queer theory. Development practitioners sometimes not only emphasize marriage and biological kinship, but when they privilege “romantic love” and sexual partners, they render invisible many significant social support unions and networks. Sharma opens an important dialog about the role of friendship as a source of possible new kin networks [

27].

Scholars note that the concept of human rights does not always translate across borders without compromise and loss. Boyce points out that much of rights language presupposes/imposes a modern subject, and he makes a distinction between modern and non-modern, a representation of subjectivity that is other than pre-modern because it does not map onto the assumption of a linear, western progress logic [

61]. Boyce further explores how the language of privacy can imply an individual disconnected from a social context, an ultimate impossibility but a frequently invoked perspective in the modern context.

Even after the United Nations declared a decade for the rights of women (1976-1985), several of the rights relating directly to women in homes and households remained beyond discussion. It is revealing that during the drafting of the 1994 Population and Development Conference’s Programme of Action in Cairo and the women’s platform in Beijing, the language of “diverse family forms” provoked strong opposition from fundamentalist groups, including the Vatican and a mixture of representatives from Christianity and Islam [

62]. Following this over a decade, it is no wonder that the human rights declaration regarding sexual orientation and gender identity that was drafted in 2007, called the Yogyakarta Principles, is still not widely accepted [

63].

Regarding the contemporary Indian context, scholars have noted that even the most recent Western sexuality categories fail to map the range and diversity of affectional and sexual practices and relationships. They especially critique the politics of Western LGBTQ+ sexual identities as they reflect liberal notions of the individual modern subject outside of history and community [

13,

64]. Many, addressing this lack of fit, have advocated the use of the term Queer as a more inclusive word that can also indicate resistance and agency and can serve as an umbrella for

hijras and a range of other local (and perhaps unnamed) sexual and gender ways. Others stress that practices are not identities but rather sometimes reflect longstanding accepted variations or fluidity. Krishnan discusses how Vanita adapts Butler’s performativity of gender for the recognition of ongoing change and interplay, which turns into

play [

65]. Other scholars question the notion of sexuality that can be a state possessed by an individual and prefer “sexualness”, which also denotes more of a fluid aspect or moment that a person might experience [

8,

13,

61].

A promising area of future research consideration involves the connections between market fundamentalisms and gender fundamentalisms globally.

2. Methods

Open-ended Interviews were conducted with emergent and snowball sampling. I constructed, tested, and followed an interview guide, and asked open-ended and follow-up questions. Interviews were initially recorded and were later transcribed. Transcribed interviews were initially read through, and themes were noted. Interviews were subsequently analyzed with open line-by-line coding, followed by focused coding in an iterative, abductive process to engage with the data and look for prominent, recurring themes. The interview analysis was done by thematic coding, using memos and coding as described by Charmaz in the framework of Grounded Theory [

66]. Prominent themes also informed the direction of subsequent participant observation. I obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) clearance for research with human subjects from Cornell University and shared this information with Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in Delhi, where I was affiliated.

Throughout my research, due to the heightened awareness and activity in social movements, civil society, and media about issues of gender and sexuality, there were many events and gatherings to attend and observe. These related to local experiences with gender and sexuality and were especially abundant before and after calendar events such as International Women’s Day, queer pride marches, and significant judicial proceedings and their anniversaries.

Participant observation was implemented in two ways for this paper. First, I attended safe-sex seminars for local university student groups, film screenings, exhibits, and panels, and participated in consultations and conferences by various groups, collectives, universities, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as celebrations and marches. These events were organized by a variety of people acting as individuals who were often but not always members of social groups and NGOs and working in professional capacities. Their efforts provided contexts in which to begin to establish community relationships with local stakeholders, enabled me to engage in a more dialogic research process and to develop situation-appropriate interview questions.

Secondly, in response to data collected from the interviews and exploratory participant observation, I deployed what I call targeted participant observation. As I analyzed interview respondent data and began to recognize emerging themes, I highlighted four events among the many I was able to attend. All were publicly accessible and were publicized in print, online, through social media, and by word of mouth. One was a craft-making workshop at a safe gathering space for transgendered people and their allies. The second was a conference relating to the right of young adults to choose their partners in marriage unions. The third event was a public celebration of the work of a well-respected feminist economist, and the fourth and fifth were a sequence of two speaker panels a month apart. One lead up to a queer pride march, and the other was held in reaction to the reinstatement of the anti-sodomy law section 377. The events are presented in chronological order. Participant observation at each event was recorded by taking off-phase field notes and was coded for emergent themes. These were then compared to themes that had emerged from respondent interview data.

Targeted Participant observation in ethnographic events:

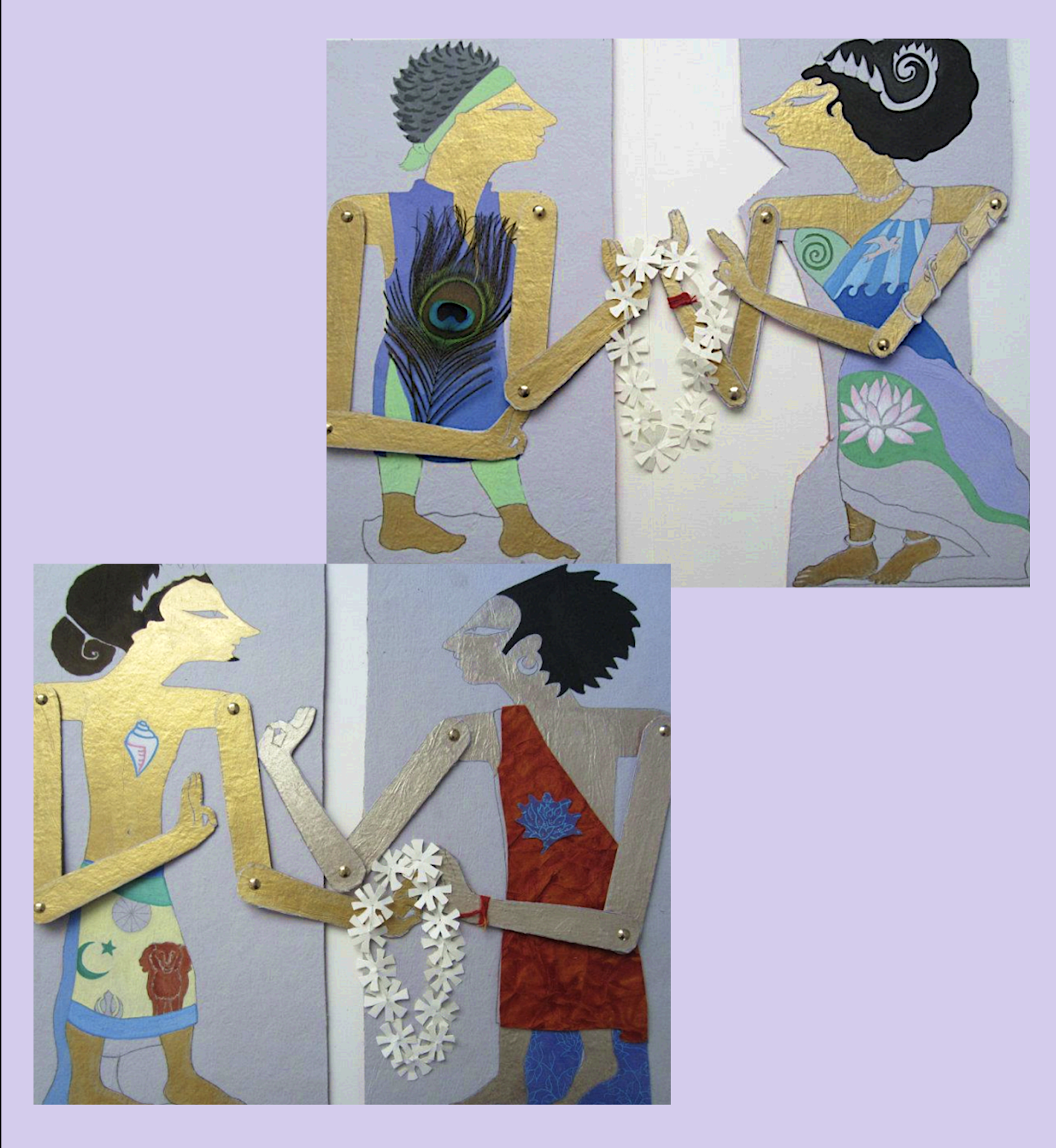

1:. The Meeting Center (not the real name). This refuge was separate from the larger, parent NGO in the Lajpat Nagar neighborhood, and served mostly as a place in which hijras, other transgender people, and their friends could socialize safe from violence and harassment. The initial focus of the Parent NGO and the Meeting Center was serving the mission of decreasing the risk and spread of HIV/AIDS and indeed, transgender people, particularly hijras, and their friends and partners came to be tested, educated, and empowered to use safer sexual practices, and condoms. They also came to build community and learn how to protect themselves and others from violence and harassment. The space became known for discussions and knowledge sharing such as safe sex workshops, and, as a health care provider, I was asked to co-facilitate one such event. The larger organization attracted positive attention and funding for its work, including a donation and visit from Lady Gaga (an internationally famous rock musician known for her advocacy of feminist and queer causes) when she performed in Delhi. It also hosted a group of Canadian documentary filmmakers who were exploring the impact of colonial sodomy laws on LGBTQ+ rights globally. One of the repeated calls for community input was to create and transfer knowledge about how to build cottage industries that could develop the skills and labor of the members and provide alternative, safe, and more reliable livelihoods than the intermittent performing, blessing, begging, or sex work that usually provided the mainstay of income for hijras. Through research and acquaintance contacts, I was invited to lead a craft workshop for a line of artistic puppets as desirable keepsakes or artwork. These were standardized shapes that allowed for flexible creativity using hand-painted designs and handmade local papers and fabrics so that each one was colorful and unique. In addition, the puppets would convey information and insight into the history and creativity of hijra and queer lives in contemporary Delhi, and their display in public places could serve as symbols of support for these marginalized people and communities. The workshop was attended by seven people who set to work with scissors, paper, paint, and thread, and we created 10 puppets. I left the design templates with managers at the center. [See

Appendix B for example puppet designs] Note: Unfortunately, the center was suddenly closed a few months afterward due to a lack of funding support and has not reopened.

2: The Right to Choice in Marriage Union Seminar (RTC seminar). This took place in the Indian Social Institute on Lodhi Road. Approximately 52 people attended this all-day event on Saturday with tea breaks and a lunch of pakoras, samosas, and dal. Approximately half of the conversation and presentations took place in Hindi and half in English, with some shorter translations back and forth. Men and women identified themselves as elected officials, local community elders, married couples who crossed convention, lawyers, police NGO and feminist collective members, journalists, and activists. All were from within or nearby Delhi, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh. The presentations and panels discussed cases in which people were prevented from forming marriage unions due to proscriptions of caste, family lineages, or as members of different religions. The authority, influence, and actions of Khap Panchayats, unelected bodies of mostly male elders, were discussed at length. Several recently publicized cases of “honour” killings by family or community members were discussed along with nationwide statistics collected by police about “honour” related violence. Moral policing and variations in regional patterns of kin and family were discussed at length. Two members of the Saheli women’s collective performed dramatic readings of several narratives representing situations in which women and men exercised their rights to choose a partner (as well as their right to not marry or choose a partner). Discussions were conducted around the implications of restricted or constrained family types. Strategies were raised within the meeting on how to broaden and build coalitions to support changes in attitudes and practices in local communities.

3: Devaki Jain’s 80th Birthday celebration. Jain is a prominent economist, feminist, researcher, lobbyist, and writer who was a founding member of the Development Alternatives for Women for a New Era (DAWN), and the Founder-Director of the Institute of Social Studies Trust (ISST). The event was hosted by people who had worked with Jain over the years, and approximately 120 people came to honor her life and work in the Indian International Center where an extensive buffet offered North Indian favorites including saag paneer, rotis, dahl, curries, and chai. Most of the evening was devoted to the substance of Jain’s work and her research revelations, especially her time studies documenting the fact that most women work regardless of whether getting paid, especially poor women. Discussions continued about her fieldwork and the formation of DAWN and the ISST. What many found surprising and provocative were discussions and disclosures about her personal life and agency, particularly regarding her family life and marriage. In a series of lively narratives from several of the panelists, (including one disclosure that seemed uncomfortable) the audience learned how Devaki had avoided a wedding in her early teens, and much later managed to propose to, marry, and have a lifelong and egalitarian relationship with a man she loved and admired. These engaging personal stories stood out against strong opposition to such agency from women, all the more so sixty years ago.

4: Two Queer Discussion Panels. One panel took place before Queer Pride (in November 2013), and the other after the reinstatement of Section 377 of IPC (in December 2013). One month apart, they reflected very different political and social climates, the tone changing in four weeks from forward-looking and celebratory to one of mourning, anger, frustration, and a resigned determination after the Koushal judgment. Packed to overflowing, these gatherings took place in large public places associated with international libraries and foundations, organized by Indian scholars and activists from Delhi and other Indian cities. For the second panel, journalists who were not from the queer or allied communities were asked not to come, so that people could speak safely and without fear of social exposure and harassment. The panelists represented a broad range from the queer community and its allies: human rights lawyers, artists, writers and lecturers, social researchers, activists; a transgender person working with an education NGO, lawyers, activist professors, writer/ historian, professor formerly at Columbia University, a co-founder of sexuality education NGO.

3. Results

Themes from interview respondents

Respondents cited Western literature and films as sources of information on sexuality but also wondered about India’s past and the Kamasutra.

Women's magazines like Cosmopolitan and Femina were some that I used to read. They’re very popular, and have a lot of social issues, in Cosmo you had those quizzes like rate how good are you in bed and those kind of things, so that is the first magazine which discussed a lot of sex. (Female, 28, heterosexual)

We found a Debonair magazine with friends while we were in a park in South Delhi playing cricket. Women were naked, mostly they were European women. My friends and I watched the movie Basic Instinct with Sharon Stone’s legs crossing and uncrossing. We all watched Baywatch for Pamela Andersen. (Male, 27, heterosexual )

Some of my friends, read Mills & Boon books, even boys. But then at that time, Baywatch changed everything! (Male, 26, gay)

I read the Kama Sutra - I must have been 22 or 23. I was curious to know about it because otherwise you never get to know this kind of thing because middle-class parents are still conservative about this. I heard some friends talking about it and I just went to a bookshop. It was interesting because there are a lot of things that happened in ancient history. We have this in our history, but now we never talk about sex. (Female, 34, heterosexual)

A bunch of my friends and I read Kama Sutra when we were age 13 or 14. We were looking for practical sex tips on being with girls. It was weird. I thought maybe I’ll understand it more when I’m older. Then we got English movies and porn magazines, and we shared those. (Male, 27, heterosexual)

In conversations during ethnographic events, people routinely cited English, European, and American sources for information and entertainment about sexuality, and in particular as sources of explicit images or narratives and information on almost any non-normative sexuality. Many said that aside from the recent court cases in the news, such media were their earliest sources of information about sex and sexuality in general as well as about queer, LGBTQ+, and transgender lives and issues.

Women expressed feelings of being enclosed, forbidden, or held back from both knowledge and mobility.

I was in a convent school and never had boys around me. I think women should step out of the boundaries and talk about it- sex. You know, rather than enclosing a girl within those areas where she should only know certain things and not more than that. I think there is a need of talking about sex because now it’s still a hidden thing. (Female, 42, heterosexual)

As I grew a little older like around 12 or 13 that’s when you know my family started telling me what to do, what not to do, when to go out, and when not to go out and they would tell me it’s not safe for girls to do this and that.

(Female, 28, heterosexual)

The girls who did have boyfriends or were indulging in sexual activity never ever-ever talked about it. It was never openly discussed. Even best friends would not tell best friends that they had slept with someone. (Female, 25, heterosexual)

Awareness is the first step to everything, you have to have the awareness, the questions. If you have questions, you just need the confidence that these questions will be answered. Otherwise, when I was young, we would stop asking questions, because knowing that no, the answers doesn’t exist or they are in a secret place or something, its forbidden, or not to be asked. (Female, 35, bisexual)

Since childhood we have been hearing this: you are a girl, you shouldn't do this, you are a girl, you shouldn't do that. We can't even talk loud. There will be like granny telling okay girls keep silence. So, why just girls? So that kind of discrimination we would feel all the time. But, since I have grown old and have moved to a metro, my parents don't have much of control over me, they don't know where I am all the time. (Female, 27, heterosexual)

The ethnography echoed these feelings of enclosure. At the celebration of her work and life, Devaki Jain spoke about some of her feelings growing up: “I wanted to be a man- if I was a boy, I wouldn’t be cloistered, I wanted to be a neurosurgeon. Women’s colleges didn’t have science, but they did have math and economics. So, I became an economist and feminist by accident.”

The Right to Choice panel was primarily about the ability of women to choose their partners, presumably based on some knowledge and mobility. At the queer panels, several people raised the issue of the double injustice of women who know nothing of their husband’s orientation being pressured into marriage with men who were gay. Both parties suffered, and the women were likely to be relatively economically dependent or disadvantaged, bringing to mind the couple in the news story at the start of this paper.

Despite the taboo, many women exercised agency to become resources for others.

In high school and then college, I was always the one my girlfriends would come to for information about sex. First it was because I read my parents medical books, then like I just looked up and found out more and more. It was pretty hush hush, but I didn’t mind talking about it. Eventually, I started volunteering with an NGO in Delhi that had a lot of good information you could count on. (Female, 28, heterosexual)

The resourcefulness of individuals was magnified when they came together. Throughout the several years of this research, I was impressed by the number, energy, and networks of formal and informal collectives and NGOs dedicated to increasing information and knowledge, access to resources, and education about health, safety, sexuality as well as economic and legal issues of concern to addressing women’s inequalities. These groups, such as Saheli and TARSHI (Talking About Reproductive and Sexual Health Issues) worked alongside and with each other to provide education, create knowledge and publications, and organize public events, actions, workshops, and film screenings. The social structures and resources women created (though ever-changing over time and with different individuals) were largely in place and subsequently functioned as models for organizations focused on queer advocacy, which came together later. Indeed, advocates and strategies often overlapped between the activities and events for women and queer people. Thus, a vacuum of formal social support for comprehensive sexual information was filled as taboo became an organizing impetus.

Men were expected to know and say more about sex and sexuality, and queer people are expected to know even more yet.

We learned about condoms in school in 12th standard in the standard curriculum, but it was really quick and sort of a joke. Plus, it was just about HIV prevention, they tried not to even say the word sex. Of course, before that everyone shared porn. The boys, I mean. But then I went to this little workshop organized by someone at uni [university]. They got a person from some organization to come in with condoms and lube and stuff and we learned how to check the date and we took one out of the package and got to see what it was like. Everybody was laughing and talking and you could ask anything. Mostly it was other gay guys, but there were a few girls too. Later, some of us told our friends about it. (Male, 22, gay)

A gay friend gave me advice about buying condoms, for some reason he just knew more about things, maybe from reading. Also, I came to know a lot more when section 377 was in the news because of the Delhi High court, it seemed like people could start talking about things, like it was more okay to talk about. Before then guys always talked about sex anyway, but we didn’t know much, it seemed to me there was just more information about sex and sexuality in general after that. (Male, 28, heterosexual)

While it appears that men have more freedom and opportunity to discuss sex and sexuality, it is worth noting some potential problems with the quality of information they are most likely to share. The types and sources of information that were most often referred to by men tended to come from personal stories, erotic popular media, and pornography, which are more instructive of certain techniques and desires rather than inclusive of emotional, health, and safety issues. The latter two were often more familiar to queer men. This probably was a result of concerns about “safe sex”: pathologizing of desires, and conflating queer lives with HIV. This position unwittingly places heterosexual people at risk as they are less likely to have access to safe sex information and practices or to regard them as applicable to their lives [

58,

67]. Perhaps because of this discrepancy, queer people were often in the position of informal peer educators to their straight friends.

Men and queer people experience more autonomy, freedom, and access to information than women, and all people react to their different levels of privilege.

Men and queer people expressed concern about how the system of gender norms is unfair to women.

This is a closed patriarchal society, and they don’t do things openly here. Families don’t talk about sex- it’s a very taboo topic. I think it’s very difficult to grow up as a girl in India. Different regions have regressive, rigid gender separations. (Male, 32, heterosexual)

I grew up with my grandmother and relatives in an extended family. I assumed gender roles from what my mom and dad did, and from TV shows. The man is the dominant one. My parents treated me and my sister very differently. I got to do a lot more, go out, have a lot of freedom. They also kept me apart from my sister and her friends. In the last few years, I started thinking about how unfair it is - that the girls can’t do very much. (Male, 24, bisexual)

Guys start talking as soon as age 11, it’s “cool” to talk about such things. Boys can talk about sex, girls can’t.

(Male, 23, gay)

If a boy has sex, he’s a player, if a girl has sex, she’s a slut. In school, boys would talk about girls in a very lurid fashion, objectifying them. (Male, 28, heterosexual)

I’ve seen female friends who didn’t know anything about sex even in college, and then they experienced things without knowing anything about them. Since I came out to a friend, she talked to me and asked me about things, otherwise she wouldn’t have known anything- even right before her marriage. (Male, 31, gay)

Both straight and queer men remarked on the enforced silence and decreased mobility of women. At the queer panels, many queer activists made repeated efforts to include concerns about the increased oppression and vulnerability of women in relation to men.

In contrast to women’s experiences of taboo as oppressive, queer men often expressed a sense of freedom in the lack of societal discussion about sexuality. In general, men have more leeway among themselves to talk and act upon matters of sex and sexuality.

I was already comfortable in my sexuality before I learnt there was any shame associated with it. (Male. 26, gay)

[About being queer] I thought I discovered something new and needed to share it with the world. (Male, 23, gay)

[About being queer] There was no shame about it, because there were no conversations about it. Now the conversations are in its initial stage and hence the shame, also because of the stigma and stereotypes that the media creates. (Male, 31, gay)

You think of heterosexual as the normative, so you would watch straight porn, but you would not care about the woman in the video. It came in very later in my mind that girls also get pleasure. (Male, 24, bisexual)

For a lot of boys, the first sexual experience is with cousins [also boys]. To anyone else, they would not even acknowledge that it happened. (Male, 27, gay)

After the initial interviews with women, this finding among queer men was at first unanticipated. In the interviews and focus group, and at the panels, it was a marked contrast to hear queer men speak of this taboo- of the lack of discussion about sexuality- in terms of freedom, almost a carte blanche. There was even a sense of exhilaration in a life that could be lived so hidden, yet almost out in the open. The contrast was striking; how in one life, taboo causes erasure or foreclosure, and in another, it can provide tacit permission. This divide even manifested in discussions relating to the recent judicial decisions around 377, with some people asking, “Why are we going public with this? Things were fine as they were, now they might get worse.”

Norms of masculinity are enforced on boys and men inside and outside of the family, while queer or transgender people are either invisible or highly marginalized and often in danger.

Pretty early on, our feminine side is more visible, so you do things a certain feminine way which gets you the backlash from adults. Luckily, my parents didn’t do that, but it happened in school, they would say, “Why are you talking like a eunuch?” (Male, 23, gay)

I had an effeminate classmate, for 10 years, no one ever talked to him. He was called a “half man”. (Male, 31, gay)

There’s these female-dressing men- called hijras. They tease boys on the trains and if you don’t give them money they’ll lift up their skirts at you and say stuff- it’s really embarrassing, and our families say to always keep away from them. But also they’ve always been there in our society going way back. I don’t know when it started. A lot of people hate them. You can’t really ask questions about them or show an interest too much, people don’t like to talk about them except to make jokes or tease other guys. (Male, 28, heterosexual)

We grew up seeing these eunuchs [a common misnomer for hijras and male to female transgendered persons used mostly by heterosexuals from outside the allied or queer communities] usually on the street or at weddings or births, but I just found out recently that there could be women, you know, women who change into or, I mean really are men inside. But I don’t think it happens much in India. (Male, 32, heterosexual)

I used to be scared and think the eunuchs were disgusting, but then I learned more and met some at a project I was working on and now I realize they are like anybody else who faces a lot of difficulties. (Female, 26, heterosexual)

[Health care provider speaking about a female to male transgender person and a female in a long-term relationship] Once two girls came to my clinic, they said they had got married and they want a child. The one was dressed up like a male and the other one was a female and the female wanted to carry a baby and asked how it is possible. I told them you can have some sperm from a sperm bank then you can have your own baby. But, in our India it’s not very open and that couple - the girl who was playing the male role, she didn’t even tell her neighbors that she is female, because they might kill her. He will always dress up like a boy and he won’t let anybody know that he is a girl. (Female, 42, heterosexual)

People who have the privacy of their bedrooms will continue to have sex without repercussions- but the people who this judgment [Koushal] really affects- anybody who doesn’t fit into hetero idea of gender with two clear boxes, male and female- people who stand out visually- are at a greater risk for violence. Just walking down the street! Most people don’t understand anybody who is not in that gender box: male-penetration, female-penetrated. How can you criminalize something when you don’t understand the very body that it concerns? Trans is not as narrow as people make it out to be. … I identify my gender as “wobbly.” My mom and my sister, they accept me like crazy. My father is supportive and loves me. At the end of the day, their only concern is that I am safe… (MTF, 23, transgender)

The enforced norms and the implied danger to those who don’t uphold them reinforce exaggerated gender performances, particularly of masculinity. The lack of acceptance and the reactions of disdain, disgust, and anger toward non-masculine men, same-sex loving men, transgender people, and women take a heavy toll of harassment and violence. Aside from very real physical violence, most commonly, the violence of non-acceptance has profound effects when men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender people, and women are denied access to employment, education, housing, and other means, access that would enable them to improve their chances to live autonomous lives. Since same-sex partnerships and hijra lineages and households are rarely recognized and cannot legally inherit or pass on property, wealth accumulation and care provision for their sick or elderly members becomes difficult if not impossible, and this poverty and vulnerability reproduce their marginal status. This is paralleled by the economic situation of single women, except for those who have independent wealth.

At the panels, advocates and activists remarked on fears of increased vulnerability for transgender people after the Koushal decision. The craft-making workshops at the Meeting Center were an effort to counter social and economic exclusion with a means of becoming economically self-sufficient outside of begging and sex work. On the other end of gender, lesbians have a low profile, and FTM people were so anomalous and unspoken of, that it was striking to hear the

hijra activists saying, “Let us not forget our brothers [FTM transgender people] among us, they are part of this struggle too.” Unlike

hijras and kothis, even more than being in

visible, FTM people are largely un

heard of. They have few identity words to mark their existence. “Sadhin” is one term that is sometimes used, though it springs from a specific region and is used as the term for women who adopt male habits and entirely renounce sexuality, once again a foreclosure and an assumption of invisible or non-existent sexual desire [

68]. Gendered violence directed towards women is dealt with extensively elsewhere including Edmunds & Gupta [

67].

Though marriage is compulsory and almost universal, women draw conflicting connections between intimacy and family, versus economic power, autonomy, and well-being. Queer people strategize for inclusion and alternative families.

There was this lady who used to come home to help mom with some stuff and I remember her telling me once about her daughter and she spoke of her daughter’s plight as having to have sex with her husband as a chore, like that’s another chore that she has to take care of along with the housework and the kids. (Female, 26, heterosexual)

I have seen that in this society, that man can have an extramarital affair and woman cannot. A man can shout and woman can’t, and a man is bread earner of the family and the woman is the piece of furniture in the house. Only the boys are supposed to be rowdy. You can’t be a rowdy person because you’re a female. So a boy can cuss and a woman cannot. I have seen all of that everyday. I see it every second in our office, in the Dhaba where we eat, everywhere the rules are always defined. (Female, 33, heterosexual)

The thing is that I totally believe in equality, but sometimes there is a kind of slavery because the man is not letting you be independent. If I want to come to meet my parents I want to have at least some amount of money where, I don’t have to ask my boyfriend, it’s my independence. I think I want to earn a little bit even if it means working hard, so that if I want to walk out of this thing, I have this choice. This is an Indian thing I guess, because in India the men work and the women stay at home. (Female, 27, heterosexual)

I think women have become more career-oriented now and finding a job is pretty natural, most women are working now, most girls want to be working so I see that as a big progress in the last 20 years. Even while I was in school or college the number one plan of action was to find the right guy and to get married and have children and settle down but now you see girls have become more independent… (Female, 24, heterosexual)

The institution of heterosexual monogamous marriage has been seen as the traditional and primary repository for female life and labor after adolescence, hence women spend a lot of time thinking (and worrying) about how they will prepare and fit themselves into it, as well as how they might resist or transform it. Jain’s life speaks of her own and other women’s work in and outside of home and marriage. The Right to Choice in Marriage (RTC) seminar dealt primarily with women and men having more control over partner choice, not only to increase acceptance and success of those unions but to eliminate the opposition and violence perpetrated by external actors seeking to control women, sexuality, and property [

67].

The queer panels were especially telling when people’s conversations turned to family formation and growing older. A group of seven close friends of mixed genders divulged a long-term dream to move to an area one by one and get jobs, buy adjoining land and build homes, and then possibly adopt and raise a few children. One laughed, noting their shared intention to just have a few children (and lampooning an old development line): “Well you know, smaller families are better!” Some at the panels wondered how and when gay marriage might become legal so partners could finally live together and seek the social protections afforded to straight couples. Another woman spoke up: “Can we talk about friends please and not just always about monogamous couples? What is it with romantic love? Isn’t there anything else?” In response, another woman added that she and four others are planning to buy property and grow old together. Similar conversations also took place among heterosexual women, as they noted all the work they were doing within as well as outside of their homes and how the labor might be more equitably shared among other women. Another conversation that came up at the Meeting Center was about how often MTF people and hijras long for male partners who can be their husbands and support them in lives outside of sex work, where they can tend to home and give care as part of families.

The ethnographic events presented venues where gender and sexuality norms and their social histories more often came under larger group scrutiny and question. These events themselves grew out of peer-to-peer interactions and organizing, beginning primarily in non-public conversations, friendships, and collegial relationships. These forums provided spaces for questions, alternatives, and new (or expanded) norms to be imagined and discussed publicly and privately. Activists, advocates, and scholars engaged with middle class publics through events, vigils, and protests as well as through multiple forms of media, social media, and journalism.

4. Discussion: Gender, Taboo, Family, and Economics

Beyond theoretical considerations, these tectonic shifts in taboo and tolerance have life-changing consequences for people. Inherently, the concepts of consent and choice regarding sex, sexuality, and/or marriage require communication. Consent is impossible to negotiate if the subjects relating to sexuality cannot speak or be spoken about. Increased public discussion of gender and sexuality, participation of women in education and workplaces, discussion of human rights, and reclaimed knowledge of pre-colonial and colonial sexualities and kinship systems, serve to slightly flatten the power gradient and decrease the violence that enforce the old norms. However, the infusion of reinvented religious fundamentalism into national politics is providing opposition to this trend. This iterative process is an uneven, staggered process.

Taboo, and the erosions of taboo, are gendered in their effects. Women are aware that they are expected to be (and are more valued when they are) ignorant, or unsullied by knowledge, of things sexual. Early in my research, one highly educated young married woman warned me not to undertake these interviews. She referred to a “chastity of knowledge”, whereby young unmarried women were not supposed to know or talk about sex or sexuality. I had never heard the phrase, and it may have been unique to her. On the other hand, men are expected to pursue information and action, yet are expected to be discrete about their desires, whatever they may be. This gendered division of taboo supports the power status quo. If women are shamed into not knowing the possibilities of sexuality, they are ill-equipped to question or explore, and the subsequent appropriation of their care labor is safely hidden in the traditional roles that precede their entrance into the marital household.

Despite and sometimes augmented by transnational rights and development languages, globalization has fueled backlashes against queer and women’s equality. Various groups play significant roles in re-enforcing gender binaries and heteronormativity under the guise of tradition [

69]. Combined with longstanding structural inequalities, this backlash makes heterosexual marriage potentially quite costly for women (sometimes literally, as with increasing dowry payments). Those women who have more personal, social, or economic resources are more likely to postpone or opt out of matrimony. Scholarship about the flight from marriage for women in Southeast and East Asia predict what we will see happening more in urban centers of India [

70]. A 2015 article by Kashyap, et al. highlights the beginning of a trend toward postponing or altogether avoiding marriage among women in South Asia [

71].

Hierarchal binary gender norms are ultimately reproduced in economic participation and autonomy and are enforced in family and peer interaction. Women were much more likely to discuss concerns about economic power and mobility regarding gender norms and gendered division of labor because they experience these as the means by which they will either access or be prevented from a broader range of opportunities and expression. Women respondents uniformly expressed anxieties and concerns with the way gender expectations and ever-present warnings or threats of violence limit their movements, education, and social participation. Some women link these threats and the lack of access to economic autonomy to the social expectations that they must inhabit underpaid, economically dependent, gendered caregiving roles upon marriage or maturity. A similar economic marginality and social vulnerability is echoed and magnified in the observations of transgender people’s economic realities. As mentioned previously, they are largely closed out of livelihood choices due to discrimination based on their often visible gender differences.

Gender Binaries and the Paradoxes of Taboo: the Meta Themes

Taboo interacts with gender and sexuality to coalesce into several themes. Maintaining rigid mutually exclusive categories of male and female relies upon the fiction of an articulable natural order and upholding taboos around discussion, challenges, or alternatives. Those invested in the power status quo mete out violence and impose silence to discourage questioning. Paradoxes emerge as taboos are exposed in processes that are political and reflexive.

Paradox 1

Taboo upholds the power status quo and provides a cover for those with privilege, yet also provokes resistance, provides an impetus for organizing, and enables community building.

Gender and sexuality issues hitherto unheard of are now being discussed due to judicial decisions, public health campaigns, popular media, activists, and the public at large. Women, queers, transgender people, and their allies are using these opportunities to open more public space about their concerns and inequalities. However, this new scrutiny also provides sometimes unwelcome public insight into previously surreptitious sexual behaviors, including those of men. Where it had provided a protected silence around some forms of gender privilege and a cover behind which people could meet others, taboo also provides a cover behind which to organize, and spurs people to share information and build community. As awareness and outreach increase, the cover of taboo withers, and with it, so does some of the safety it has provided.

Paradox 2

When does consent matter: examining the disjuncture between heterosexual marital rape exceptions vs consensual queer “unnatural acts”.

Consent and choice regarding sex, sexuality, and/or marriage require communication. People must be able to speak about subjects relating to sexuality to negotiate this terrain. The recent judgments discussed at the beginning of this paper have provided opportunities to question whether coercion or consent can be considered normal or natural and what bodies, institutions, or authorities have the power to make such determinations.

The gender order in Delhi presents paradoxical binds for transgendered persons, women and men in the law, in social norms, and their everyday lives. Regarding section 377 IPC, Koushal, NALSA, and NAZ introduce the tension between universal human rights and whether some sexualities or sexual acts are considered legitimate or criminal. By upholding the exception of rape within marriage in sections 375 and 376 IPC, the anti-rape laws all but nullify the need for a woman’s consent [

72]. While this is a problem for women, little attention is given to the bind confronting heterosexual men who learn from such a system that consent is not needed, or that “good” women will not/cannot give consent. How is a kind man to ask or proceed? How can a desirable and desiring woman say yes?

In contrast, the language condemning “acts against the order of nature” in section 377, calls for the criminalization of any people who engage in non-reproductive sexual acts even when they are consensual. Though the case is often made 377 targets primarily queer/SOGI people and is largely only symbolic for most heterosexual people, the Koushal judgment significantly sends clear signals about what sorts of sexuality will and won’t be tolerated. These issues have profound impacts on the social and emotional lives and aspirations of all people, privileging heterosexual relationships even if they are abusive, and restricting the knowledge and imaginations regarding possible other forms of sexualities, affective bonds, and family forms. Consent aside, if same-sex love is unnatural, is marital rape natural?

Paradox 3

Transgender people have rights, but queers are still criminals, and women are still subordinate. Does the concept of transgender simultaneously reinforce and destabilize the hierarchal gender binary?

In the India of post-NAZ, Koushal, and NALSA, unanswered questions arose: How would Indian society move forward from this moment? Will the rigid male/female hierarchy in social norms and the resulting social disparities be somewhat ameliorated? Or will the legal institutionalization of a third gender disarticulate from the other two genders, leaving the hierarchy intact? Will newly won rights introduce measures of economic reparations for transgender persons while women struggle as ever with relative poverty and economic dependence? How will the social and economic gains of transgendered people impact their desires for sexuality and family? What will change for lesbian, bisexual, and gay Indians whose desires are still deemed criminal?

On one hand, enforcing the marginality of transgender people reinforces the centrality of the hierarchal male/female binary. When transgender people are legally invisible, unrecognized, and outcast, they are unprotected and vulnerable to harassment and violence. Furthermore, they are seen as a threat to order, and their vulnerability is held out as a warning to women and men who don’t conform to gender norms. Paradoxically, when transgender people gain the status of a legally recognized third sex, it may unintentionally preserve the hierarchal binary by providing another fixed category, which is distinct from the male/female pairing. The social discomfort and ambiguity of blurred gender boundaries can be relieved by either viewing transgender people as moving from one primary gender to the other or by seeing them as altogether separate.

Paradox 4

Illusions of Progress? Reexamining Western attitudes about gender, women, and sexuality.

Communities in which women have exercised expanded power and agency, as well as those which accepted and celebrated the queer people in their midst, are far from being Western imports to India. On the contrary, colonialism and Western markets have sometimes deepened gender inequalities. Activists express concern and skepticism about aligning themselves with global LGBTQ+ movements as scholars reveal the extent of colonial and elite control over men and women, sexuality and gender, and the ways that various social kinship and sexuality histories have been erased. Viewed in a longer and larger context, western development projects to empower women, or advance gender and queer equality are seen by some as matters of a sort of amnesia [

73]. Along similar lines, Spivak has famously critiqued the global north for its mission of “saving brown women from brown men” [

74](p.296). However, the history of pre-colonizing Europe suggests a deeply inconsistent intention toward women. I posit that if it was not wholly unwitting, part of the historical colonial strategy was to enforce white (European) binaries onto all people. A colonizing or imperial effort to “save women” from any type of subjugation would be a strategic later development.

This imposition of gender and sexuality binaries is starkly evident in the enactment of Section 377, the anti-sodomy law in 1870 as it criminalizes consensual sexual acts that are non-reproductive and privileges heterosexual vaginal/penile intercourse. In addition to gender, other categories such as class/caste and religion have served similar binary impositions. Another example of such enforcement and imposition of a binary was manifested in the political geography of India’s Partition, in which many Hindus and Muslims who had been living throughout the sub-continent were forced to leave their homes and migrate across newly formed national boundaries. However, in the case of gender, rather than attribute well-thought-out plans to the colonial actors, we now have hindsight into the self-inflicted European trauma in which many generations of women were tortured and killed during “witch-hunts” by elites of their own communities. The erasures the colonizers propagated in colonial lands may have been less a result of planning and power, and more of inherited blindness and terror. By the time they had set up trade and imposed rule, they couldn’t see women with power and property, couldn’t see queer kinship.

Paradox 5