Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

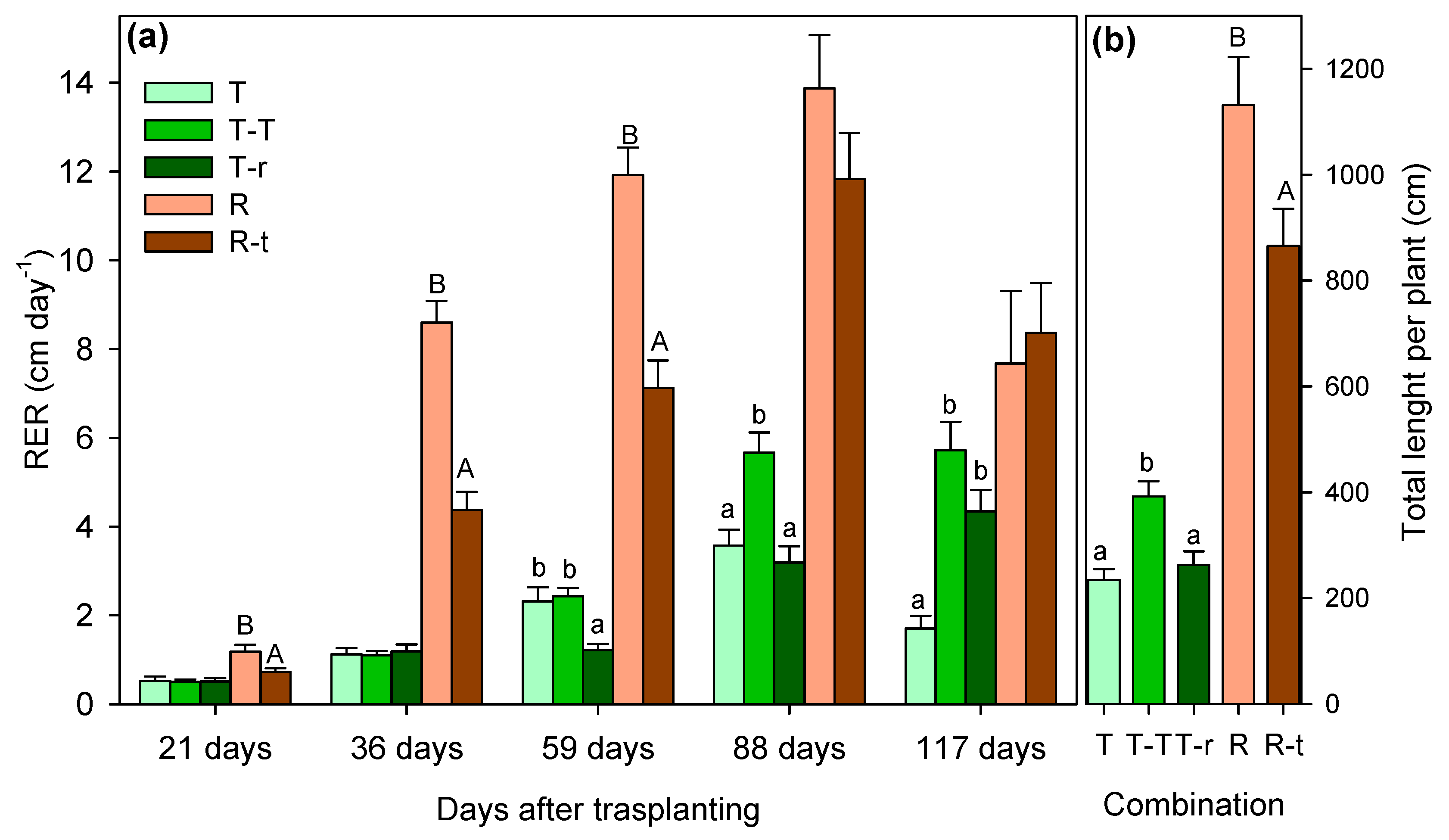

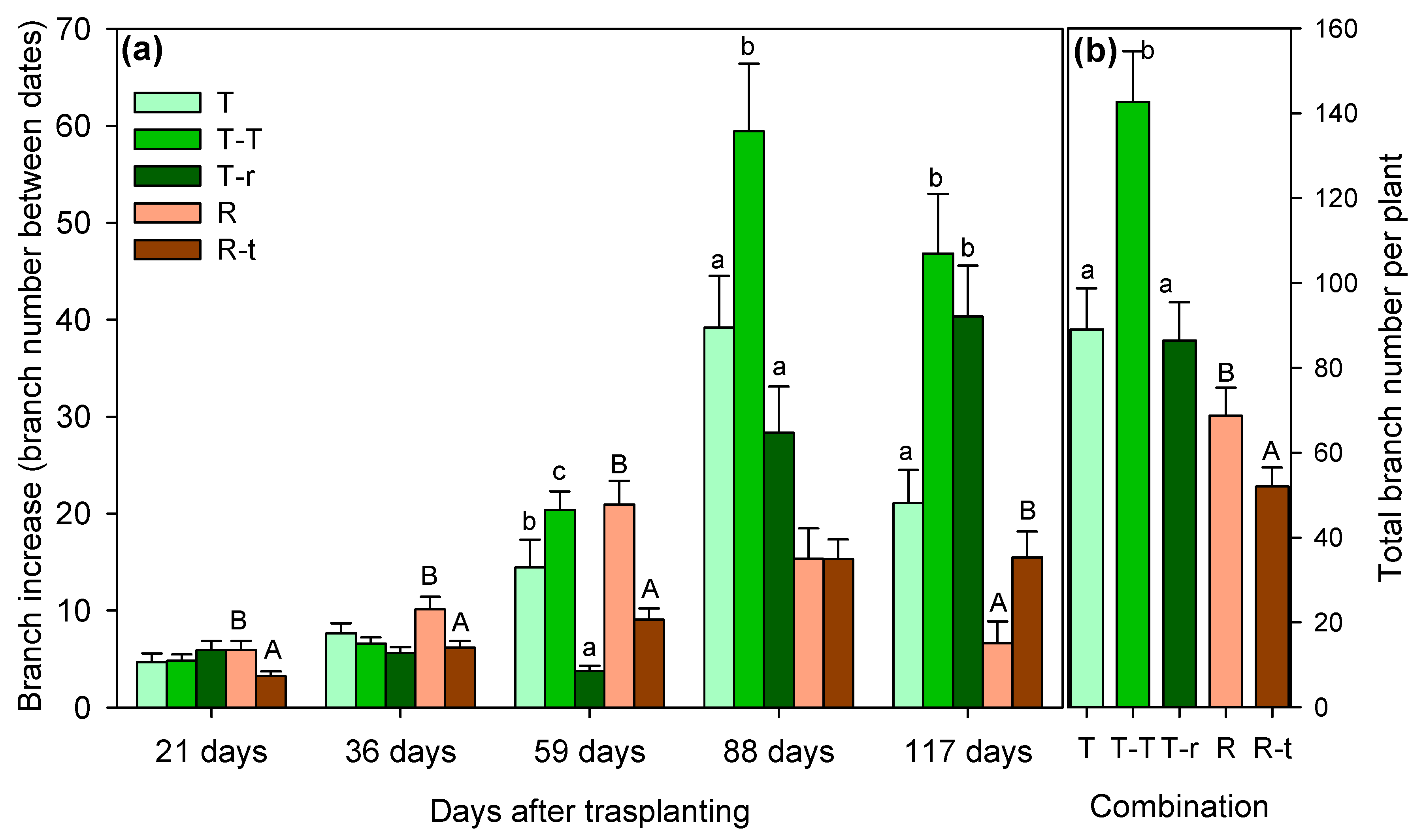

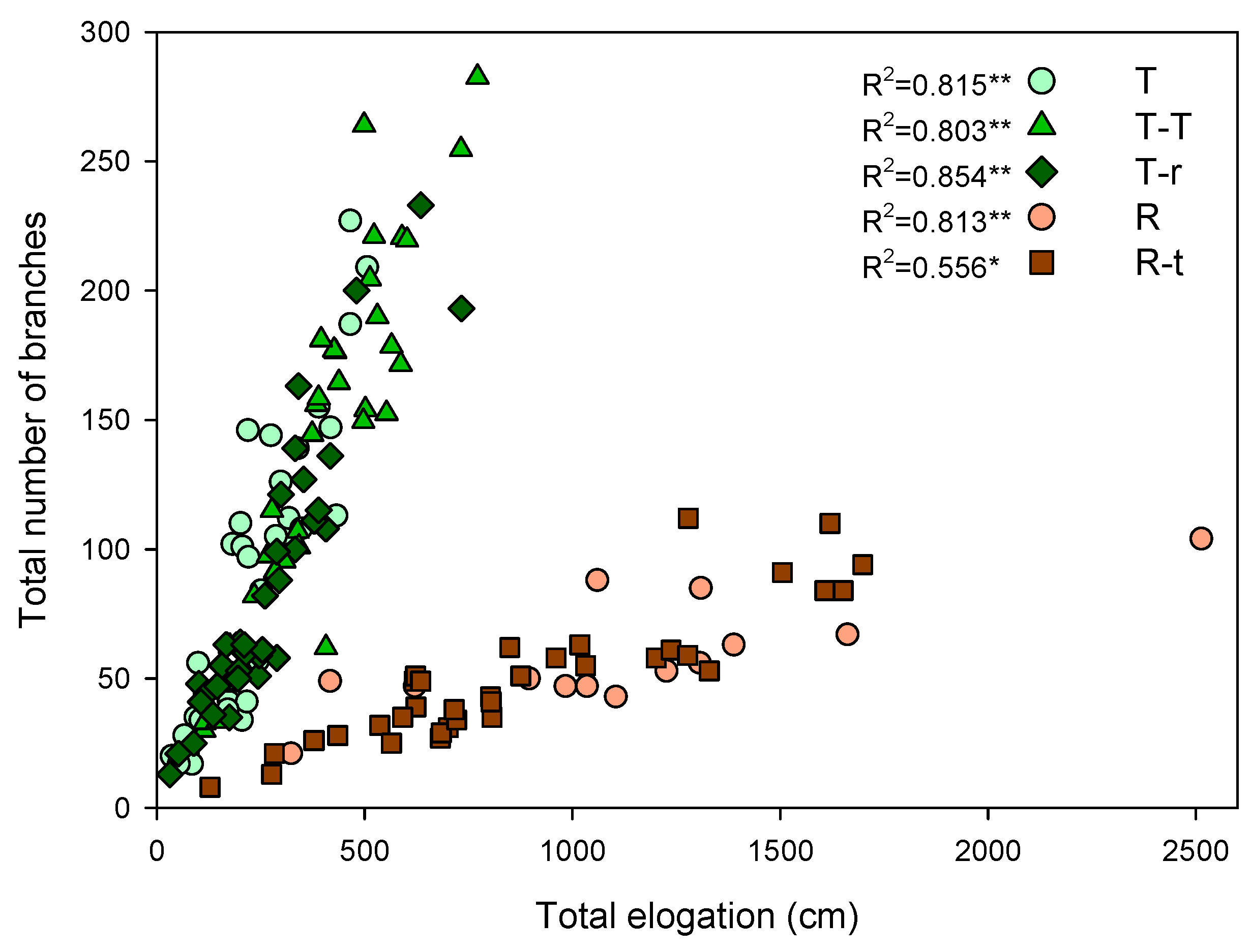

2.1. Growth Pattern Before the Water Restriction Experiment

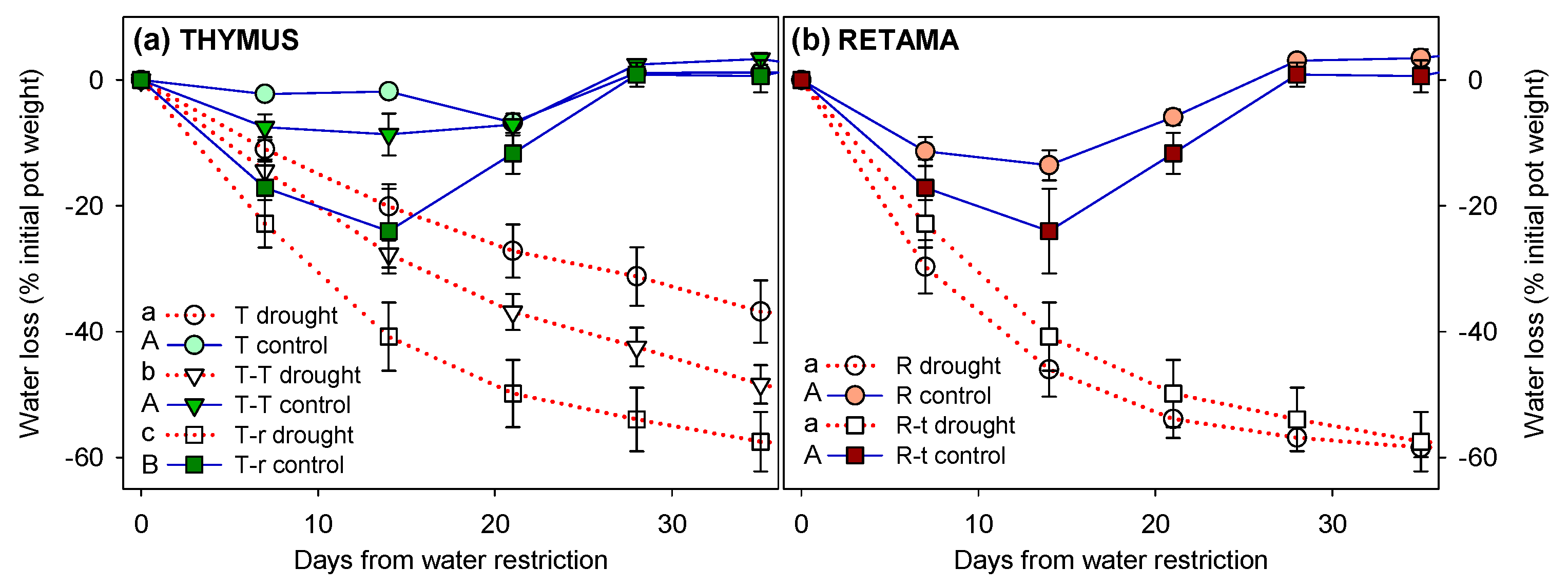

2.2. Water Restriction Experiment

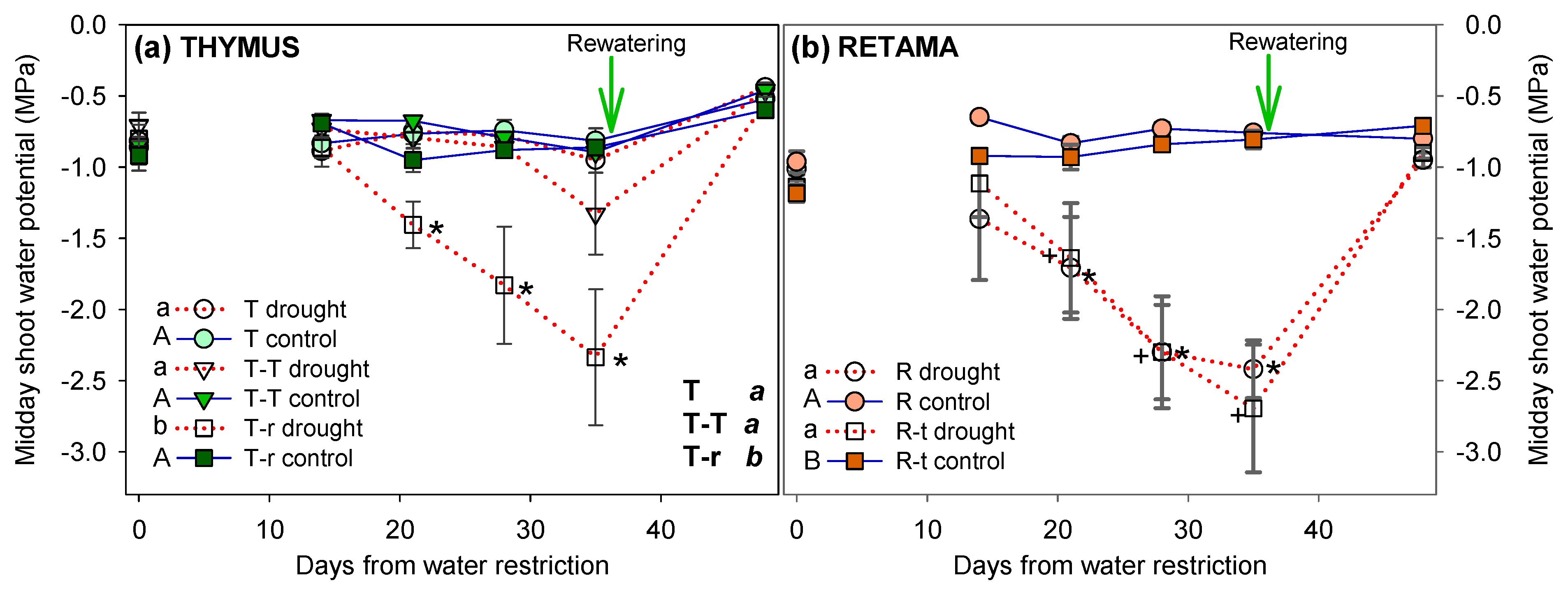

2.2.1. Shoot Water Potential

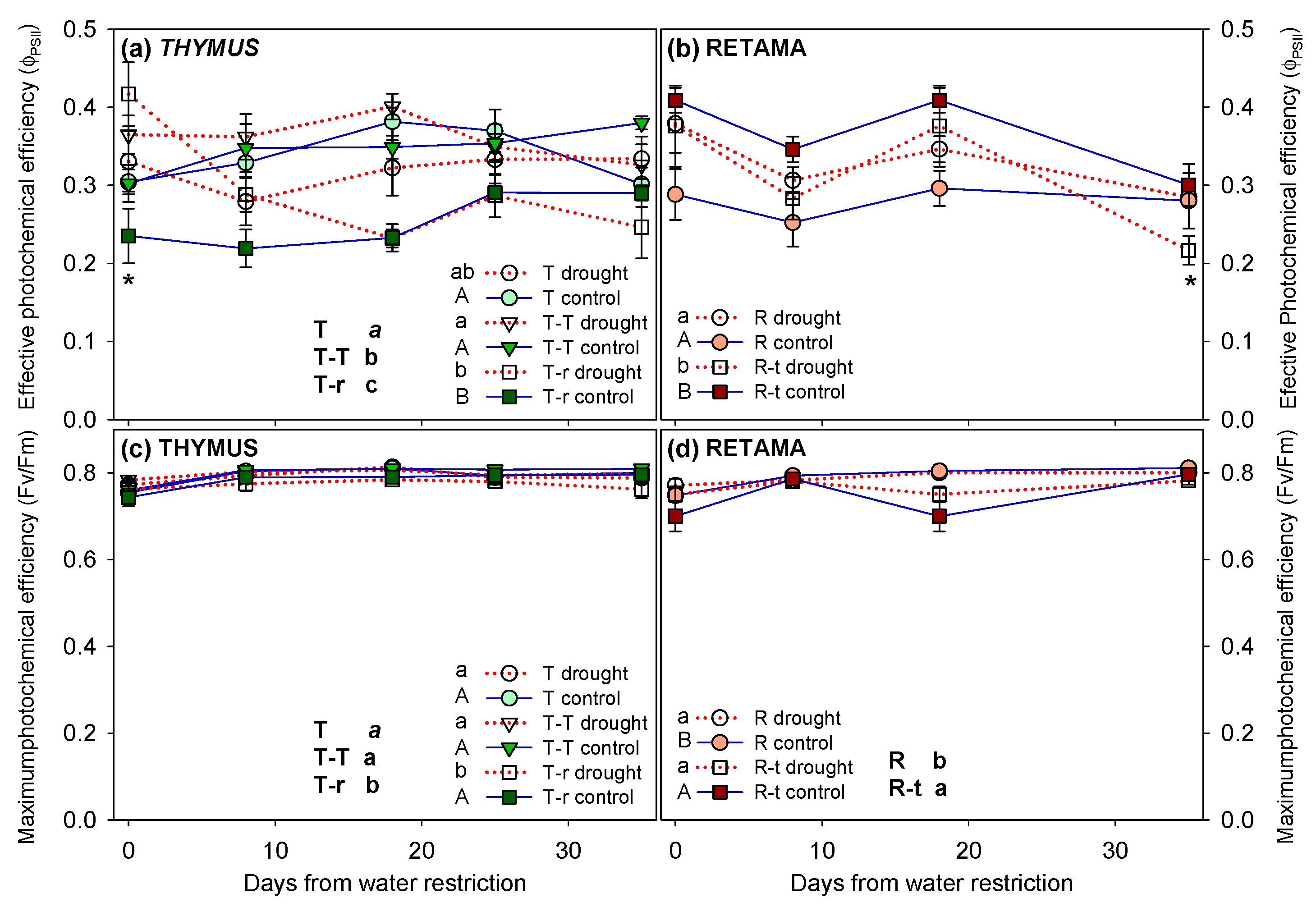

2.2.2. Photochemical Efficiency

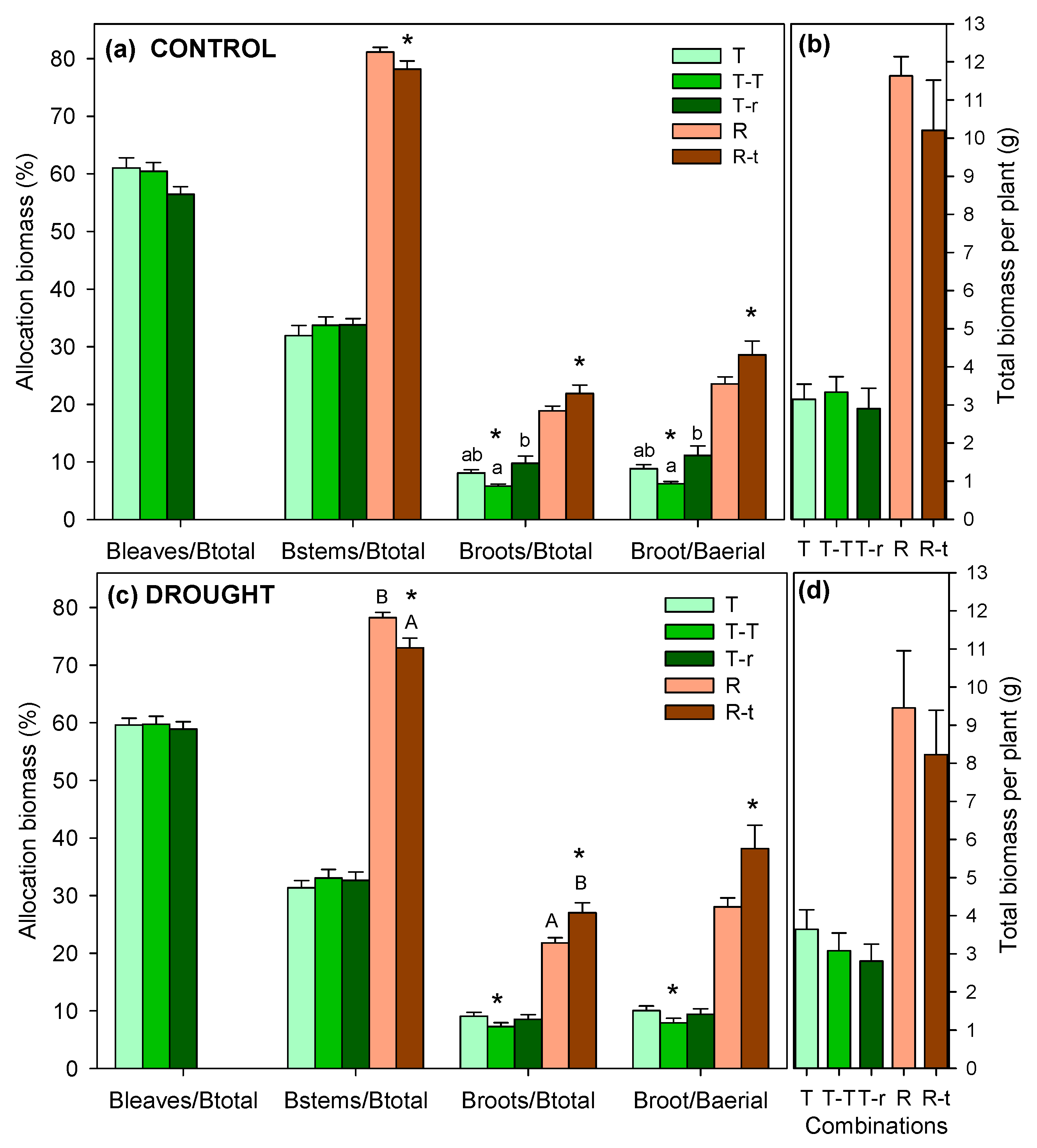

2.3. Biomass Allocation

2.4. Leaf Chemistry Analyses

3. Discussion

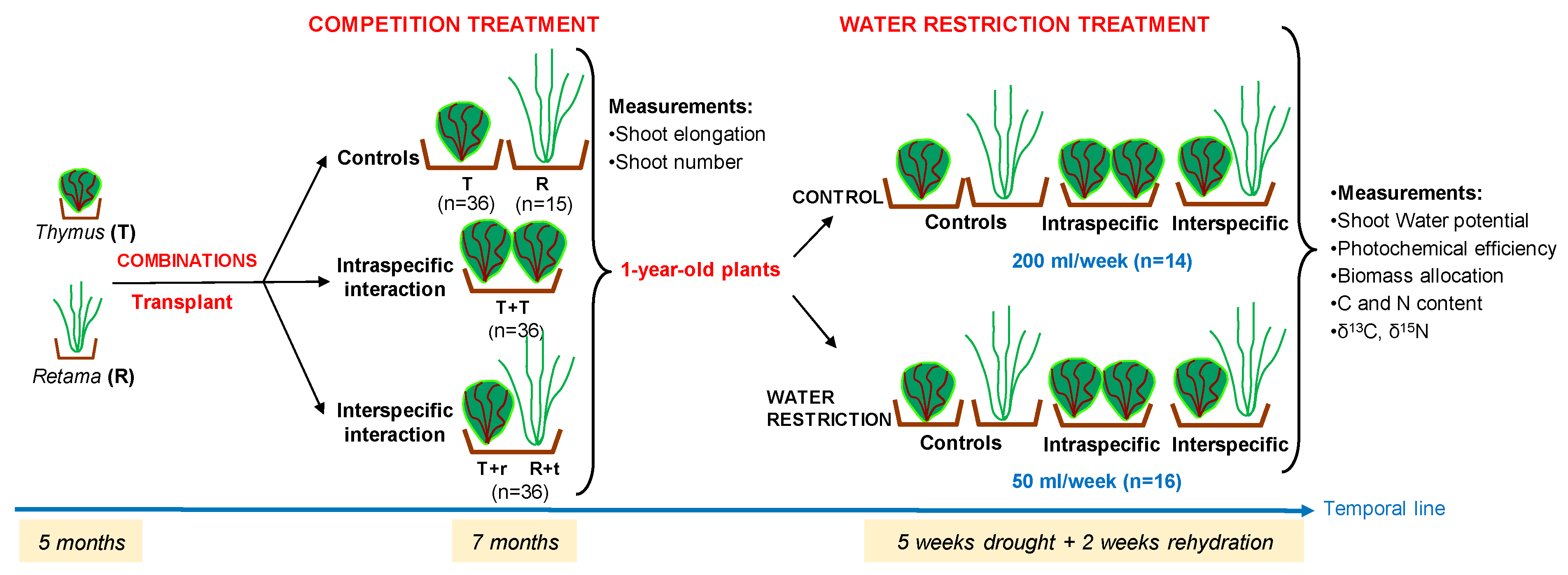

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Species

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Plant Transplanting

- Control: 36 pots with one Thymus plant (T) and 15 pots with one Retama plant (R);

- Intraspecific competition: 36 pots with two Thymus plants (T-T),

- Interspecific competition 36 pots with one Thymus and one Retama plant, (T-r or R-t).

4.4. Morphological Measurements

4.5. Water Restriction Experiment

4.6. Physiological Measurements

4.7. Biomass Measurement

4.8. Leaf and Cladodes Isotopic Analysis and N and C Content

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RER | Relative elongation rate; |

| ΔR | Branching increment; |

| Ψm | Shoot water potential |

| ΦPSII | Effective photochemical efficiency; |

| Fv/Fm | Maximum photochemical efficiency; |

| BL/BT | Leaf mass allocation |

| BS/BT | Stem mass allocation |

| BR/BT | Root mass allocation |

| BR/BA | Root biomass to aboveground biomass ratio; |

| δ13C | Carbon isotope signature (¹³C/¹²C) |

| δ15N | Nitrogen isotope signature (¹⁵N/¹⁴N) |

Appendix A

References

- Kaisermann, A.; de Vries, F.T.; Griffiths, R.I.; Bardgett, R.D. Legacy Effects of Drought on Plant–Soil Feedbacks and Plant–Plant Interactions. New Phytologist 2017, 215, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Putten, W.H.; Bardgett, R.D.; Bever, J.D.; Bezemer, T.M.; Casper, B.B.; Fukami, T.; Kardol, P.; Klironomos, J.N.; Kulmatiski, A.; Schweitzer, J.A.; et al. Plant–Soil Feedbacks: The Past, the Present and Future Challenges. Journal of Ecology 2013, 101, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, R.W. Plant–Plant Interactions and Environmental Change. New Phytologist 2006, 171, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, W.M.; Williams, A.P.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Adams, H.D.; Klein, T.; López, R.; Sáenz-Romero, C.; Hartmann, H.; Breshears, D.D.; Allen, C.D. Global Field Observations of Tree Die-off Reveal Hotter-Drought Fingerprint for Earth’s Forests. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, F.; Jaime, L.A.; Margalef-Marrase, J.; Pérez-Navarro, M.A.; Batllori, E. Short-Term Forest Resilience after Drought-Induced Die-off in Southwestern European Forests. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 806, 150940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardol, P.; Campany, C.E.; Souza, L.; Norby, R.J.; Weltzin, J.F.; Classen, A.T. Climate Change Effects on Plant Biomass Alter Dominance Patterns and Community Evenness in an Experimental Old-Field Ecosystem. Global Change Biology 2010, 16, 2676–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploughe, L.W.; Jacobs, E.M.; Frank, G.S.; Greenler, S.M.; Smith, M.D.; Dukes, J.S. Community Response to Extreme Drought (CRED): A Framework for Drought-Induced Shifts in Plant–Plant Interactions. New Phytologist 2019, 222, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenari, M.; Noy-Meir, I.; Goodall, D.W. Hot Deserts and Arid Shrublands; Elsevier, 1985; ISBN 978-0-444-42296-5.

- Padilla, F.M.; Miranda, J.D.; Jorquera, M.J.; Pugnaire, F.I. Variability in Amount and Frequency of Water Supply Affects Roots but Not Growth of Arid Shrubs. Plant Ecol 2009, 204, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart-Haëntjens, E.; De Boeck, H.J.; Lemoine, N.P.; Mänd, P.; Kröel-Dulay, G.; Schmidt, I.K.; Jentsch, A.; Stampfli, A.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Bahn, M.; et al. Mean Annual Precipitation Predicts Primary Production Resistance and Resilience to Extreme Drought. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 636, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, R.; Rambal, S.; Ratte, J.P. The Dehesa System of Southern Spain and Portugal as a Natural Ecosystem Mimic. Agroforestry Systems 1999, 45, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifan, M.; Tielbörger, K.; Kadmon, R. Direct and Indirect Interactions among Plants Explain Counterintuitive Positive Drought Effects on an Eastern Mediterranean Shrub Species. Oikos 2010, 119, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Maarel, E. Dry Coastal Ecosystems: Polar Regions and Europe; Ecosystems of the world, 2A; London: Amsterdam. 1993; ISBN 978-0-444-87348-4. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC Climate Change 2023 Synthesis Report. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115 ISBN. [CrossRef]

- Maestre, F.; Eldridge, D.; Soliveres, S.; Kéfi, S.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Bowker, M.; García-Palacios, P.; Gaitan, J.; Gallardo, A.; Lazaro, R.; et al. Structure and Functioning of Dryland Ecosystems in a Changing World. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2016, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazarra Bernabé, A.; Lorenzo Mariño, B.; Romero Fresneda, R.; Moreno García, J.V. Evolución de los climas de Köppen en España en el periodo 1951-2020; Agencia Estatal de Meteorología, 2022.

- Lavorel, S.; Canadell, J.; Rambal, S.; Terradas, J. Mediterranean Terrestrial Ecosystems: Research Priorities on Global Change Effects. Global Ecology & Biogeography Letters 1998, 7, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, R.; Vilà, M. Response of the Invader Cortaderia Selloana and Two Coexisting Natives to Competition and Water Stress. Biol Invasions 2008, 10, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, J.P.; Hillier, S.H. The Contribution of Seedling Regeneration to the Structure and Dynamics of Plant Communities, Ecosystems and Larger Units of the Landscape. Seeds: the ecology of regeneration in plant communities 2000, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.L. Population Biology of Plants; Academic Press, 1977; ISBN 978-0-12-325850-2.

- Evans, C.E.; Etherington, J.R. The Effect of Soil Water Potential on Seedling Growth of Some British Plants. New Phytologist 1991, 118, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niering, W.A.; Whittaker, R.H.; Lowe, C.H. The Saguaro: A Population in Relation to Environment. Science 1963, 142, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingo, A. Size-Uneven Competition and Resource Availability: A Factorial Experiment on Seedling Establishment of Three Mediterranean Species. Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology 2009, 143, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, R.; Pugnaire, F. Facilitation in Plant Communities. Functional Plant Ecology 1999, 623–648. [Google Scholar]

- Pugnaire, F.I.; Luque, M.T. Changes in Plant Interactions along a Gradient of Environmental Stress. Oikos 2001, 93, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, R. Nutritive Influences on the Distribution of Dry Matter in the Plant. NJAS 1962, 10, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peperkorn, R.; Werner, C.; Beyschlag, W. Phenotypic Plasticity of an Invasive Acacia versus Two Native Mediterranean Species. Funct Plant Biol 2005, 32, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S.K.; Wanek, W. Use of Decreasing Foliar Carbon Isotope Discrimination during Water Limitation as a Carbon Tracer to Study Whole Plant Carbon Allocation. Plant, Cell & Environment 2002, 25, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Nagel, O.W. The Role of Biomass Allocation in the Growth Response of Plants to Different Levels of Light, CO2, Nutrients and Water: A Quantitative Review. Functional Plant Biology 2000, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Huston, M. A Theory of the Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Plant Communities. Vegetatio 1989, 83, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisson, J.; Reynolds, J.F. Effects of Compensatory Growth on Population Processes: A Simulation Study. Ecology 1997, 78, 2378–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, B.B.; Jackson, R.B. Plant Competition Underground. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 1997, 28, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.D.; Grime, J.P. A New Method of Exposing Developing Root Systems to Controlled Patchiness in Mineral Nutrient Supply. Annals of Botany 1989, 63, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kroons, H.; Hutchings, M.J. Morphological Plasticity in Clonal Plants: The Foraging Concept Reconsidered. Journal of Ecology 1995, 83, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersani, M.; Abramsky, Z.; Falik, O. Density-Dependent Habitat Selection in Plants. Evolutionary Ecology 1998, 12, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahall, B.E.; Callaway, R.M. Root Communication among Desert Shrubs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1991, 88, 874–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenk, H.J. Root Competition: Beyond Resource Depletion. Journal of Ecology 2006, 94, 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersani, M.; Brown, J. s.; O’Brien, E.E.; Maina, G.M.; Abramsky, Z. Tragedy of the Commons as a Result of Root Competition. Journal of Ecology 2001, 89, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas, C.; Pugnaire, F.I. Belowground Zone of Influence in a Tussock Grass Species. Acta Oecologica 2011, 37, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, H.P.; Vepachedu, R.; Gilroy, S.; Callaway, R.M.; Vivanco, J.M. Allelopathy and Exotic Plant Invasion: From Molecules and Genes to Species Interactions. Science 2003, 301, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, C.; Weston, L.A.; Huang, T.; Jander, G.; Owens, T.; Meinwald, J.; Schroeder, F.C. Grass Roots Chemistry: Meta-Tyrosine, an Herbicidal Nonprotein Amino Acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 16964–16969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, F.; Hertel, D.; Jung, K.; Fender, A.-C.; Leuschner, C. Competition Effects on Fine Root Survival of Fagus Sylvatica and Fraxinus Excelsior. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 302, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M.M.; Manwaring, J.H.; Durham, S.L. Species Interactions at the Level of Fine Roots in the Field: Influence of Soil Nutrient Heterogeneity and Plant Size. Oecologia 1996, 106, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Salvador, P.; Cuesta, B. Retama Monosperma (L.) Boiss. y Retama Sphaerocarpa (L.) Boiss. In; 2013; pp. 342–353 ISBN 978-84-8014-846-7.

- Kith y Tasara, M. El problema de las dunas del SO de España. Montes 1946, 11, 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- Möllerová, J. Notes on Invasive and Expansive Trees and Shrubs. J. For. Sci. 2005, 51, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejda, M.; Sádlo, J.; Kutlvašr, J.; Petřík, P.; Vítková, M.; Vojík, M.; Pyšek, P.; Pergl, J. Impact of Invasive and Native Dominants on Species Richness and Diversity of Plant Communities. Preslia 2021, 93, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivias, M.P.; Zunzunegui, M.; Díaz Barradas, M.C.; Álvarez-Cansino, L. Competitive Effect of a Native-Invasive Species on a Threatened Shrub in a Mediterranean Dune System. Oecologia 2015, 177, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Vallés, S.; B. Gallego Fernández, J.; Dellafiore, C.; Cambrollé, J. Effects on Soil, Microclimate and Vegetation of the Native-Invasive Retama Monosperma (L.) in Coastal Dunes. Plant Ecol 2011, 212, 169–179. [CrossRef]

- García-de-Lomas, J.; Fernández, L.; Martín, I.; Saavedra, C.; Rodríguez-Hiraldo, C.; Gallego-Fernández, J.B. Management of Coastal Dunes Affected by Shrub Encroachment: Are Rabbits an Ally or an Enemy of Restoration? J Coast Conserv 2023, 27, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivias, M.P.; Zunzunegui, M.; Barradas, M.C.D.; Álvarez-Cansino, L. The Role of Water Use and Uptake on Two Mediterranean Shrubs’ Interaction in a Brackish Coastal Dune Ecosystem. Ecohydrology 2014, 7, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunzunegui, M.; Esquivias, M.; Oppo; Gallego-Fernández, J. Interspecific Competition and Livestock Disturbance Control the Spatial Patterns of Two Coastal Dune Shrubs. Plant and Soil 2012, 354, 299–309. [CrossRef]

- Naumann, G.; Alfieri, L.; Wyser, K.; Mentaschi, L.; Betts, R.A.; Carrao, H.; Spinoni, J.; Vogt, J.; Feyen, L. Global Changes in Drought Conditions Under Different Levels of Warming. Geophysical Research Letters 2018, 45, 3285–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Poorter, H. Inherent Variation in Growth Rate Between Higher Plants: A Search for Physiological Causes and Ecological Consequences. In Advances in Ecological Research; Begon, M., Fitter, A.H., Eds.; Academic Press, 1992; Vol. 23, pp. 187–261.

- Rascher, K.G.; Hellmann, C.; Máguas, C.; Werner, C. Community Scale 15N Isoscapes: Tracing the Spatial Impact of an Exotic N2-Fixing Invader. Ecology Letters 2012, 15, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, G.; Facelli, J.M. Growth and Competition of Cytisus Scoparius, an Invasive Shrub, and Australian Native Shrubs. Plant Ecology 1999, 144, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, A.; McIntire, E.J.B. Under Strong Niche Overlap Conspecifics Do Not Compete but Help Each Other to Survive: Facilitation at the Intraspecific Level. Journal of Ecology 2011, 99, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Oró, D.; Parraga-Aguado, I.; Querejeta, J.I.; Conesa, H.M. Importance of Intra- and Interspecific Plant Interactions for the Phytomanagement of Semiarid Mine Tailings Using the Tree Species Pinus Halepensis. Chemosphere 2017, 186, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, A.E.; Hughes, A.R. Genotypic Diversity Weakens Competition within, but Not between, Plant Species. Journal of Ecology 2020, 108, 2212–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas, C.; Pugnaire, F.I. Plant Interactions Govern Population Dynamics in a Semi-arid Plant Community. Journal of Ecology 2005, 93, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munné-Bosch, S.; Alegre, L. The Xanthophyll Cycle Is Induced by Light Irrespective of Water Status in Field-Grown Lavender (Lavandula Stoechas) Plants. Physiologia Plantarum 2000, 108, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genty, B.; Briantais, J.-M.; Silva, J.B.V.D. Effects of Drought on Primary Photosynthetic Processes of Cotton Leaves. Plant Physiology 1987, 83, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Munné-Bosch, S.; Llusià, J.; Filella, I. Leaf Reflectance and Photo- and Antioxidant Protection in Field-Grown Summer-Stressed Phillyrea Angustifolia. Optical Signals of Oxidative Stress? New Phytologist 2004, 162, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Sánchez-Gómez, D. Ecophysiological Traits Associated with Drought in Mediterranean Tree Seedlings: Individual Responses versus Interspecific Trends in Eleven Species. Plant Biology 2006, 8, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway, R.M.; Walker, L.R. Competition and Facilitation: A Synthetic Approach to Interactions in Plant Communities. Ecology 1997, 78, 1958–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, F.T.; Callaway, R.M.; Valladares, F.; Lortie, C.J. Refining the Stress-gradient Hypothesis for Competition and Facilitation in Plant Communities. Journal of Ecology 2009, 97, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno, T.E.; Escudero, A.; Valladares, F. Different Intra- and Interspecific Facilitation Mechanisms between Two Mediterranean Trees under a Climate Change Scenario. Oecologia 2015, 177, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Aparicio, L. The Role of Plant Interactions in the Restoration of Degraded Ecosystems: A Meta-Analysis across Life-Forms and Ecosystems. Journal of Ecology 2009, 97, 1202–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M.; Gómez-Aparicio, L.; Quero, J.L.; Valladares, F. Non-Linear Effects of Drought under Shade: Reconciling Physiological and Ecological Models in Plant Communities. Oecologia 2012, 169, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaniemi, T.K. Why Does Fertilization Reduce Plant Species Diversity? Testing Three Competition-Based Hypotheses. Journal of Ecology 2002, 90, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Plant-Soil Interactions in Mediterranean Forest and Shrublands: Impacts of Climatic Change. Plant Soil 2013, 365, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, O.; Martins, A.; Catarino, F. Comparative Phenology and Seasonal Foliar Nitrogen Variation in Mediterranean Species of Portugal. Ecologia Mediterranean 1992, 18, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Correia, O.; Beyschlag, W. Two Different Strategies of Mediterranean Macchia Plants to Avoid Photoinhibitory Damage by Excessive Radiation Levels during Summer Drought. Acta Oecologica 1999, 20, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.J.; Reynolds, J.F. Potential Growth and Drought Tolerance of Eight Desert Grasses: Lack of a Trade-Off? Oecologia 2000, 123, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Walters, M.B.; Vanderklein, D.W.; Buschena, C. Close Association of RGR, Leaf and Root Morphology, Seed Mass and Shade Tolerance in Seedlings of Nine Boreal Tree Species Grown in High and Low Light. Functional Ecology 1998, 12, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, A.; Stewart, J.; Robinson, D.; Griffiths, B.S.; Fitter, A.H. Spatial and Physical Heterogeneity of N Supply from Soil Does Not Influence N Capture by Two Grass Species. Functional Ecology 2000, 14, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, B.E.; Blicker, P.S. Response of the Invasive Centaurea Maculosa and Two Native Grasses to N-Pulses. Plant and Soil 2003, 254, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T.E.; Mambelli, S.; Plamboeck, A.H.; Templer, P.H.; Tu, K.P. Stable Isotopes in Plant Ecology. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 2002, 33, 507–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, P. Tansley Review No. 95 15 N Natural Abundance in Soil-Plant Systems. New Phytol 1997, 137, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.D. Physiological Mechanisms Influencing Plant Nitrogen Isotope Composition. Trends in Plant Science 2001, 6, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Högberg, P. Nitrogen Isotopes Link Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plants to Nitrogen Dynamics. New Phytologist 2012, 196, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelissen, J.; Lavorel, S.; Garnier, E.; Diaz, S.; Buchmann, N.; Gurvich, D.; Reich, P.; ter Steege, H.; Morgan, H.D.G.; Van der Heijden, M.; et al. Handbook of Protocols for Standardised and Easy Measurement of Plant Functional Traits Worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany, v.51, 335-380 (2003) 2003, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezudo, B.; Talavera, S.; Blanca, G.; Cueto, M.; Valdés, B.; Hernández Bermejo, J.; Herrera, C.; Rodríguez Hiraldo, C.; Navas, D. Lista roja de la flora vascular de Andalucía; Consejería de Medio Ambiente: Sevilla, 2005; p. 126 p.; ISBN 978-84-96329-62-1.

- Carapeto, A.; Francisco, A.; Pereira, P.; Porto, M. Lista Vermelha da Flora Vascular de Portugal Continental.; Botânica em Português; Sociedade Portuguesa de Botânica, Associação Portuguesa de Ciência da Vegetação – PHYTOS e Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas.; Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda: Lisboa, 2000; Vol. 7; ISBN 978-972-27-2876.

- Directiva 97/62/CE Directiva 97/62/CE del Consejo de 27 de octubre de 1997 por la que se adapta al progreso científico y técnico la Directiva 92/43/CEE, relativa a la conservación de los hábitats naturales y de fauna y flora silvestres; 1997; Vol. 305.

- Talavera, S.; Castroviejo, S. Flora Iberica: plantas vasculares de la Penínsular Ibérica e Islas Baleares : Vol. VII (I) Leguminosae (partim); Editorial CSIC - CSIC Press, 1999; ISBN 978-84-00-07821-8.

- Gallego-Fernández, J.B.; Muñoz-Valles, S.; Dellafiore, C.M. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Colonization and Expansion of Retama Monosperma on Developing Coastal Dunes. J Coast Conserv 2015, 19, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Vallés, S.; Gallego-Fernández, J.B.; Cambrollé, J. The Role of the Expansion of Native-Invasive Plant Species in Coastal Dunes: The Case of Retama Monosperma in SW Spain. Acta Oecologica 2014, 54, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fernández, M.; Gómez Gutiérrez, J.M.; Pérez-Fernández, M.; Gómez Gutiérrez, J.M. Importancia e interpretación de la latencia y germinación de semillas en ambientes naturales. In Proceedings of the Restauración de ecosistemas mediterráneos; Universidad de Alcalá, 2003; pp. 87–112.

- Pérez-Fernández, M.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.M. Importancia e Interpretación de La Latencia y Germinación de Semillas En Ambientes Naturales. In; 2003; pp. 87–112 ISBN 978-84-8138-549-6.

- Streeter, J.; Wong, P.P. Inhibition of Legume Nodule Formation and N2 Fixation by Nitrate. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 1988, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, S.T.; Vogt, K.A.; Grier, C.C. Carbon Dynamics of Rocky Mountain Douglas-Fir: Influence of Water and Nutrient Availability. Ecological Monographs 1992, 62, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.R.; Keith Owens, M. Growth and Biomass Allocation of Shrub and Grass Seedlings in Response to Predicted Changes in Precipitation Seasonality. Plant Ecology 2003, 168, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RER | Thymus | Retama | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F | P | df | F | P | |

| Competition | 2 | 6.8 | 0.001 | 1 | 4.678 | 0.036 |

| Time | 4 | 318.5 | 0.001 | 4 | 46.332 | 0.000 |

| Competition*Time | 8 | 10.1 | 0.001 | 4 | 0.548 | 0.463 |

| Ψm | ΦPSII | Fv/Fm | |||||||

| Thymus | df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P |

| Competition | 2 | 15.830 | 0.001 | 2 | 26.994 | 0.001 | 2 | 15.486 | 0.001 |

| Watering | 1 | 13.621 | 0.001 | 1 | 2.091 | 0.150 | 1 | 2.199 | 0.140 |

| Time | 5 | 13.089 | 0.001 | 4 | 0.954 | 0.434 | 4 | 20.989 | 0.001 |

| C * W | 2 | 8.641 | 0.001 | 2 | 3.156 | 0.045 | 2 | 0.883 | 0.415 |

| C * T | 10 | 2.805 | 0.003 | 8 | 2.630 | 0.009 | 8 | 0.454 | 0.887 |

| W * T | 5 | 5.607 | 0.001 | 4 | 5.110 | 0.001 | 4 | 5.057 | 0.001 |

| C * W * T | 10 | 2.437 | 0.009 | 8 | 2.424 | 0.016 | 8 | 0.229 | 0.985 |

| Retama | df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P |

| Competition | 1 | 0.240 | 0.625 | 1 | 0.225 | 0.636 | 1 | 8.335 | 0.005 |

| Watering | 1 | 52.657 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.983 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.977 |

| Time | 5 | 6.152 | 0.001 | 3 | 8.028 | 0.001 | 3 | 13.240 | 0.001 |

| C * W | 1 | 0.198 | 0.657 | 1 | 15.172 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.030 | 0.864 |

| C * T | 5 | 0.108 | 0.990 | 3 | 1.964 | 0.125 | 3 | 0.859 | 0.466 |

| W * T | 5 | 7.250 | 0.001 | 3 | 1.263 | 0.292 | 3 | 3.348 | 0.022 |

| C * W * T | 5 | 0.266 | 0.931 | 3 | 0.194 | 0.900 | 3 | 0.621 | 0.603 |

| Thymus | BL/BT | BS/BT | BR/BT | BR/BA | ||||||||

| df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | |

| Competition | 2 | 1.520 | 0.225 | 2 | 0.881 | 0.418 | 2 | 7.339 | 0.001 | 2 | 6.996 | 0.002 |

| Watering | 1 | 0.135 | 0.715 | 1 | 0.467 | 0.496 | 1 | 0.418 | 0.520 | 1 | 0.287 | 0.593 |

| C*W | 2 | 0.656 | 0.522 | 2 | 0.021 | 0.979 | 2 | 1.949 | 0.149 | 2 | 1.988 | 0.143 |

| BS/BT | BR/BT | BR/BA | ||||||||||

| Retama | df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | |||

| Competition | 1 | 5.618 | 0.023 | 1 | 5.618 | 0.023 | 1 | 4.719 | 0.036 | |||

| Watering | 1 | 5.456 | 0.025 | 1 | 5.456 | 0.025 | 1 | 4.115 | 0.050 | |||

| C*W | 1 | 0.449 | 0.507 | 1 | 0.449 | 0.507 | 1 | 0.551 | 0.463 | |||

| %C | %N | C/N | δ13C | δ15N | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment | C | D | C | D | C | D | C | D | C | D | |||||||||||

| T | Mean | 47.9 | ab | 47.9 | a | 1.5 | 1.4 | 32.8 | 39.7 | -28.8 | -27.0 | a | 5.1 | a | 4.1 | a | |||||

| SD | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 9.7 | 16.1 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | |||||||||||

| T-T | Mean | 49.1 | a | 49.0 | a | 1.7 | 1.5 | 31.8 | 34.5 | -28.5 | -28.6 | ab | 3.7 | ab | 3.3 | ab | |||||

| SD | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | |||||||||||

| T-r | Mean | 49.6 | a | 50.0 | a | 1.4 | 1.6 | 35.3 | 33.9 | -29.1 | -29.3 | ab | 2.8 | b | 2.6 | b | |||||

| SD | 3.6 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 6.3 | 9.7 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 1.0 | |||||||||||

| R-t | Mean | 42.9 | b | 42.9 | b | 1.4 | 1.3 | 32.9 | 36.2 | -30.5 | -31.3 | b | 2.5 | b | 2.7 | b | |||||

| SD | 1.6 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.0 | |||||||||||

| % C | % N | C/N | δ13C | δ15N | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | |

| Competition | 3 | 20.886 | 0.001 | 3 | 0.956 | 0.423 | 3 | 0.359 | 0.783 | 3 | 4.212 | 0.011 | 3 | 6.698 | 0.001 |

| Watering | 1 | 0.038 | 0.847 | 1 | 0.940 | 0.338 | 1 | 1.554 | 0.220 | 1 | 0.059 | 0.809 | 1 | 1.114 | 0.297 |

| C*W | 3 | 0.029 | 0.993 | 3 | 0.632 | 0.599 | 3 | 0.638 | 0.595 | 3 | 0.684 | 0.567 | 3 | 0.380 | 0.768 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).