1. Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are an incretin-based class of medications initially developed for type 2 diabetes and are now also approved for obesity treatment [

1]. By mimicking the gut hormone GLP-1, these agents stimulate glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppress glucagon (a key hormone that regulates blood sugar levels), slow gastric emptying, and influence central appetite centers to reduce food intake [

2]. Consequently, GLP-1 RAs, such as semaglutide and liraglutide, can lead to substantial weight loss along with improved glycemic control and reduced cardiovascular risk [

2]. This effectiveness has resulted in the unprecedented popularity of GLP-1 RAs for weight management in recent years.

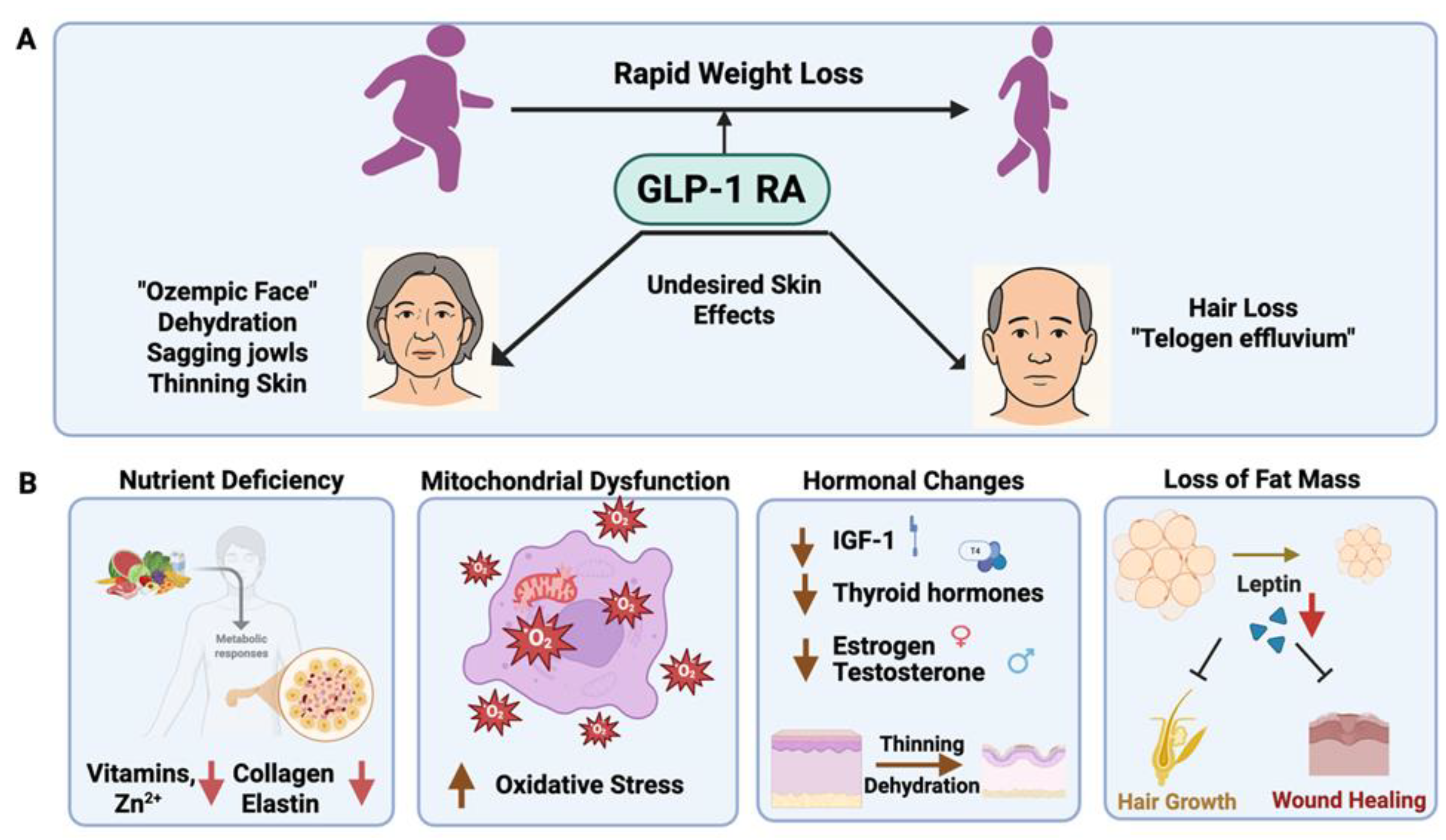

However, the rapid and significant weight loss induced by GLP-1 RAs has also highlighted several dermatological side effects. Patients undergoing long-term GLP-1 RA therapy have reported various adverse skin manifestations. Some of these are directly related to the medication (e.g., injection site reactions, drug-induced immune responses), but most are secondary to the weight loss and metabolic changes (e.g., loss of facial fat, skin sagging, hair shedding) [

3]. For instance, the term “Ozempic face” has entered popular discourse to describe the gaunt, aged facial appearance resulting from GLP-1 RA-associated fat loss in the midface and temples [

2,

3]. Concurrently, dermatologists are noting increased cases of diffuse hair loss (telogen effluvium) in patients who experienced rapid weight reduction on these drugs [

4]. These emerging dermatologic issues underscore the importance of awareness among healthcare providers and patients, as they can significantly impact quality of life and may necessitate co-management with dermatology specialists.

This review aims to comprehensively examine the adverse dermatological effects of GLP-1 RAs, compiling evidence from clinical studies, case reports, and relevant mechanistic research. We hypothesize mechanisms by which GLP-1 RAs may impair skin integrity, collagen synthesis, hydration, and mitochondrial function, all factors that contribute to skin aging. When available, data from human and animal studies are discussed to analyze these effects. Finally, we present a section on potential therapeutic approaches to prevent or mitigate GLP-1 RA-related skin issues, focusing on the use of over-the-counter compounds aimed at preserving skin health during GLP-1 RA therapy.

2. Systemic Metabolic Effects of GLP-1 RAs

To contextualize the skin-specific outcomes, it is important to understand the systemic metabolic actions of GLP-1 RAs. By activating GLP-1 receptors in pancreatic β cells, these drugs enhance insulin release in response to elevated blood glucose while also inhibiting glucagon secretion from alpha cells [

5,

6]. Additionally, GLP-1 receptors in the gastrointestinal tract and brain mediate slowed gastric emptying and increased satiety, leading to reduced caloric intake [

5]. Clinically, these effects result in improved glycemic control and significant weight loss. For example, a pivotal trial of once-weekly semaglutide in obese adults demonstrated an average weight reduction of around 15% over 68 weeks, far exceeding that of the placebo [

2]. GLP-1 RAs also tend to lower blood pressure and improve lipid profiles, and large outcome studies have shown benefits in reducing cardiovascular events in diabetic patients [

7,

8].

From a dermatological perspective, weight loss and improvements in glycemic control offer theoretical benefits, including reduced insulin resistance and inflammation. Improved glycemic control can decrease the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) that stiffen collagen and contribute to skin aging, while lower systemic inflammation may promote skin health. In fact, GLP-1 RAs have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects in other contexts, and

beneficial dermatological outcomes, including improved psoriasis and wound healing, have been reported in patients on GLP-1 RAs [

9]. However, these positive effects might be counterbalanced or overshadowed by negative impacts on the skin arising from the drugs’ potent catabolic action. The accelerated weight loss and appetite suppression induced by GLP-1 RAs can create a situation in which skin structure and function are compromised, either through nutritional deficiencies, loss of structural subcutaneous fat, or off-target effects of the drug on the skin. The following sections outline the adverse dermatological outcomes associated with GLP-1 RAs and propose the underlying mechanisms.

3. Dermatological Adverse Effects of GLP-1 RAs

3.1. Changes in Skin Integrity and Elasticity (“Ozempic Face”)

A prominent dermatologic concern with GLP-1 RAs arises from the changes in body composition they induce. Significant fat loss, particularly if rapid, can lead to visible changes in skin firmness and integrity. As subcutaneous fat diminishes, the skin may appear looser or saggy because the support structure that once upheld it (the fat and connective tissue) has been reduced. This effect is most noticeable in the face, where even small volumes of fat loss in the cheeks, temples, and orbital area can lead to pronounced hollowing, accentuation of wrinkles, and descent of facial tissues. Patients experiencing these changes often report looking older or more tired, a phenomenon popularly dubbed “Ozempic face” when associated with semaglutide use. In a review of aesthetic issues related to GLP-1 RAs, researchers noted that midfacial fat loss and deflation of the buccal fat pads contribute to deeper nasolabial folds, sunken eyes, and sagging jowls [

3] (

Figure 1A). These are classic signs of facial aging that, in the context of GLP-1-induced weight loss, can manifest over a short time span, surprising patients.

It is important to note that skin laxity after weight loss is a well-known phenomenon, even in non-pharmacological weight loss contexts such as post-bariatric surgery. Rapid or massive weight loss exceeds the skin’s ability to contract, resulting in redundant, sagging skin. Histological and biophysical studies of skin in post-bariatric patients have shown alterations in collagen and elastin content [

10]. After significant weight loss, the dermis often exhibits fewer thick collagen bundles and a higher proportion of thin, disorganized collagen fibers, indicative of remodeling and loss of tensile strength [

10]. In one study of patients who lost weight after bariatric surgery, collagen fiber volume in skin samples was found to decrease from ~41% to 32%, accompanied by an increase in elastic fiber density, an adaptive response to compensate for elasticity, yet insufficient to prevent overall laxity [

10]. Although similar detailed skin biopsies have not yet been reported in GLP-1 RA patients, it is reasonable to expect parallel changes when weight loss is comparable. Indeed, weight loss from GLP-1 RAs (which can exceed 20–30 kg in some individuals) may produce excess skin on the body (e.g., abdominal apron, loose arm skin) and loss of dermal thickness in the face, analogous to changes seen after other rapid weight loss interventions. The skin’s structural integrity is compromised partly because collagen synthesis is reduced during and after the catabolic state of weight loss. Adipose tissue itself produces collagen (particularly type VI collagen within fat’s extracellular matrix), and in obesity, there is often excess collagen deposition (fibrosis) in fat tissue [

11]. With rapid fat loss, collagen production in adipose tissue drops and existing fibrous support may not adequately re-form in time to support the deflated skin [

10,

12]. Moreover, caloric restriction can downregulate skin fibroblast activity and collagen production temporarily. One clinical study found that the magnitude of fat mass reduction was negatively correlated with collagen accumulation in skin. As fat mass decreased, the collagen content in the dermis and around adipocytes also decreased [

13]. This loss of collagen scaffolding contributes to the reduced mechanical stability of post-weight-loss skin and manifests as softness, crepe-like texture, and wrinkles.

In summary, GLP-1 RA-induced weight loss can accelerate visible skin aging by reducing both adipose tissue volume and structural proteins (collagen, elastin) that keep skin firm. Patients in their 40s and 50s who experience drastic weight loss might notice that pre-existing fine lines and folds become more pronounced, while overall skin tone becomes lax. Younger patients may also find that their “baby fat” is gone, resulting in a sharper but sometimes gaunt facial appearance. These changes are cosmetic and not life-threatening, but they can have psychological impacts. It is reported that some individuals discontinue otherwise successful GLP-1 therapy because they are distressed by the aged look it gives them.

3.2. Skin Dehydration

Hydration is a crucial element of skin health that may be indirectly influenced by GLP-1 RA therapy (

Figure 1A). Some patients using GLP-1 RAs report that their skin feels drier or less supple during treatment. There are several plausible explanations for this observation. First, GLP-1 RAs often lead to gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and reduced appetite, which can result in dehydration if patients do not maintain their fluid intake [

14]. Even mild, subclinical dehydration can manifest in the skin as dryness and dullness, since the outer stratum corneum relies on sufficient water content. Second, decreased oral intake (especially if patients reduce their consumption of water-rich foods or forget to drink due to diminished thirst cues) might lower overall skin hydration. Third, rapid weight loss can impact sebaceous gland activity and hormone levels, sometimes resulting in temporary drier skin or alterations in the skin’s surface lipids [

15].

While direct studies on skin hydration in GLP-1 RA users are lacking, general principles from dermatology suggest that maintaining hydration and the skin barrier is vital during weight loss. Proper hydration ensures that the epidermis retains flexibility and an intact barrier, while dehydration can increase trans epidermal water loss and make the skin more susceptible to irritation or eczema. Interestingly, some research indicates that GLP-1 may play a role in skin physiology: one laboratory study found that activating GLP-1 receptors can increase the production of hyaluronic acid in fibroblasts, potentially improving skin moisture (this is speculative and based on cellular models). Clinically, however, the overall effect in patients seems to be that without conscious effort to stay hydrated, the skin may experience dryness as a side effect of GLP-1 therapy [

4].

Another factor is nutrition: weight loss, especially if rapid, can lead to deficiencies in essential nutrients (fats, vitamins, zinc, etc.) that are important for skin hydration and barrier lipids. If patients inadvertently consume very low-fat diets while on GLP-1 RAs (due to reduced appetite), they may impair the skin’s ability to produce its natural oils and lipid components, particularly ceramides. Ceramides are crucial molecules in the stratum corneum that maintain barrier function and prevent water loss. A deficiency in dietary essential fatty acids or overall caloric malnutrition can cause xerosis (dry, scaly skin) in extreme cases. Even moderate changes could shift someone from having well-hydrated skin to experiencing dryness. Therefore, ensuring balanced nutrition during GLP-1–induced weight loss is vital for skin integrity.

Supportive evidence comes from general skin health studies: Adequate hydration and intake of antioxidants and micronutrients correlate with better skin elasticity and moisture retention [

16]. For example, Manzoni et al. reviewed that a balanced diet and sufficient water intake support collagen synthesis and help mitigate oxidative stress in the skin, thereby maintaining hydration and delaying aging [

16]. In practical terms, patients on GLP-1 RAs should be advised to drink plenty of fluids and use moisturizers to reinforce their skin barrier. In summary, while GLP-1 RAs do not directly “dry out” the skin in a pharmacologic sense, the side effects and lifestyle changes associated with their use can compromise skin hydration and barrier function, warranting proactive measures to keep the skin moisturized.

3.3. Hair Loss and Other Appendage Effects

Dermatologists have recently observed a higher incidence of hair shedding in patients on GLP-1 RAs, particularly those experiencing rapid weight loss [

17]. In a retrospective cohort study at a dermatology center, 35 out of 283 patients (approximately 12%) on GLP-1 RA therapy exhibited new-onset diffuse hair loss (telogen effluvium) or worsening of a pre-existing hair thinning condition [

4]. The hair loss generally presents as increased shedding (e.g., hair coming out in brushes or showers) a few months into therapy (

Figure 1A). Telogen effluvium is likely the diagnosis in many cases – this condition represents a stress-induced shift of hair follicles from the growing (anagen) phase to the resting/shedding (telogen) phase. Significant weight loss can be a trigger for telogen effluvium [

18]; this is frequently observed after bariatric surgery or crash dieting. The physiological stress of sudden calorie reduction, along with possible transient nutrient deficiencies (such as inadequate protein, iron, or zinc), can shock hair follicles into shedding. GLP-1 RA patients often lose weight at a rate of over 0.5–1 kg per week in the initial months, which is sufficient to precipitate telogen effluvium in susceptible individuals. Additionally, one theory suggests that GLP-1 RAs might directly impact hair follicles or the hormonal environment that supports hair growth [

17]. GLP-1 receptors have been identified in various tissues, and it is theorized that altering metabolic pathways could influence the hair growth cycle. Another hypothesis relates to thyroid function: rapid weight loss can lead to a decrease in T3 (triiodothyronine) hormone as the body adapts metabolically, and lower thyroid levels can contribute to hair thinning. While there is a lack of concrete evidence for a direct pharmacologic effect on hair, the correlation between starting GLP-1 RAs and subsequent hair loss in multiple patient reports indicates more than coincidence.

Besides hair, other skin appendages may also be affected by metabolic changes. Some reports indicate increased brittle nails or slowed nail growth in patients after significant weight loss [

19], likely due to similar mechanisms of nutrient repartitioning. On the flip side, positive effects on appendages have been observed in isolated cases: e.g., improved psoriasis and reduced hidradenitis suppurativa flares with GLP-1 RA therapy, presumably from reduced inflammation [

20]. In summary, hair loss is an important dermatological consideration for GLP-1 RA patients, but it should be manageable with supportive care and typically regrows once the body adapts to the new weight.

4. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying GLP-1 RA Effects on Skin

These dermatologic effects induced by GLP-1 RAs can involve both direct drug actions and the indirect consequences of weight loss and metabolic changes. Several cellular and molecular mechanisms have been proposed (

Figure 1B):

4.1. Catabolic and Nutrient State Change

GLP-1 RAs create a calorie deficit that leads to weight loss. Rapid weight loss essentially results in a controlled catabolic state, where the body breaks down fat (and to some extent lean mass) for energy. This condition can divert nutrients away from non-essential functions like hair growth and skin turnover. If protein intake is not sufficiently maintained, the body prioritizes vital organs over collagen production, which may reduce collagen synthesis in the skin. Additionally, drastic reductions in body fat can lower levels of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and essential fatty acids, crucial for maintaining skin and hair health. For example, vitamin A and zinc are necessary for epidermal cell proliferation [

21]; deficiencies may result in dry, rough skin. Thus, the beneficial metabolic weight loss effect of GLP-1 RAs comes at the cost of stressing the integumentary system due to relative nutrient scarcity and rapid remodeling demands.

4.2. Hormonal and Endocrine Level Change

Weight loss and reduced caloric intake can lead to lower levels of anabolic hormones like IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1), thyroid hormones, and sex hormones (estrogen and testosterone) [

22]. IGF-1 is known to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and collagen production; thus, reduced IGF-1 could slow dermal matrix production. In women, significant weight loss sometimes causes menstrual irregularities and lower estrogen levels; estrogen plays an important role in skin thickness and hydration (post-menopausal estrogen decline causes skin dryness and thinning) [

23]. Therefore, GLP-1 RA-induced weight loss might mimic some features of hormonal aging in the skin.

4.3. Fat Mass Reduction

Adipose tissue is not just a fat store; it also houses and secretes hormones (like leptin and adiponectin) and growth factors that affect the skin. Leptin, for instance, can promote wound healing and hair follicle cycling. A sudden loss of fat mass results in decreased leptin levels. Low leptin has been associated with hair loss and delayed wound healing in some studies [

24,

25]. Additionally, adipose tissue contains adipose-derived stem cells in the dermal-subcutaneous junction that can differentiate into fibroblasts or other cells involved in skin repair [

26]. Some dermatologists have speculated that with rapid fat depletion, these local stem cells may be less active (“turned off”), potentially impairing skin regeneration and collagen renewal [

3]. This concept was mentioned by aesthetic physicians observing Ozempic face – the idea that reduced facial fat might mean fewer signals to maintain dermal thickness, since facial fat pads and dermal fibroblasts crosstalk in maintaining youthful skin.

4.4. Mitochondrial Function and Oxidative Stress

Skin aging is closely linked to mitochondrial function in cells. Mitochondria generate the energy (ATP) required for collagen synthesis, cell division, and overall skin biosynthetic activity [

27]. Caloric restriction, as induced by GLP-1 RAs, can have complex effects on mitochondria. Some data indicate that chronic caloric restriction may enhance mitochondrial efficiency and reduce reactive oxygen species, potentially slowing intrinsic aging [

28]. Conversely, if weight loss occurs rapidly and is accompanied by stress, it might temporarily increase oxidative stress (from rapid fat oxidation) and could even diminish mitochondrial biogenesis in peripheral tissues [

29]. Some studies suggest a potential downregulation of mitochondrial activity in peripheral tissues by GLP-1 RAs, which may contribute to symptoms such as fatigue and impaired tissue regeneration [

2]. One might also extrapolate from related fields. For instance, in cases of malnutrition or eating disorders, skin and hair suffer due to impaired cellular energy metabolism [

30]. It is plausible that some patients on GLP-1 RAs experience a milder version of this – their skin cells might not receive optimal energy or substrates, resulting in slower turnover and repair. This could present as a sallow complexion or delayed healing of minor skin damage. Additionally, thyroid hormone (which declines with weight loss) is a crucial regulator of mitochondrial function; low T3 could reduce mitochondrial activity in skin cells [

31].

In summary, the mechanisms are multifactorial. Rapid weight loss is the central driver, bringing along downstream effects (nutrient deficits, hormonal changes, oxidative stress) that collectively impact skin and hair. The drug itself may exert subtle direct effects, but most negative dermatologic outcomes can be traced back to the consequences of weight and fat reduction. This understanding is useful because it highlights mitigation strategies: if we can support the skin through the stress of weight loss, we may reduce these side effects.

5. Strategies to Mitigate GLP1-RA’s Skin Effects

Considering the variety of dermatological issues that can arise from GLP-1 RA therapy, it is crucial to address how to prevent or mitigate these effects without compromising the metabolic benefits. In clinical practice, dermatologists and plastic surgeons have managed “Ozempic face” by using dermal fillers to restore volume or energy-based skin-tightening procedures, such as radiofrequency or ultrasound, to stimulate new collagen and tighten skin. Such interventions can partially reverse the aesthetic impacts by encouraging collagen synthesis and mechanically lifting sagging areas. Here, we explore several strategies and compounds, such as ceramides, methylene blue, and retinoids, all of which have shown promise in mitigating the skin-related side effects. These approaches are designed for simple, at-home skincare remedies rather than clinical interventions, making them easily accessible yet scientifically grounded. A comprehensive approach is recommended for severe cases, merging general skincare principles with specific interventions.

5.1. Supplementing Ceramide in skin moisturizers:

Emerging research suggests that GLP-1 RAs may reduce ceramide levels in the body [

32]. For instance, the LiraFlame trial demonstrated that liraglutide downregulated several lipid species, including ceramides, in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Mechanistically, GLP-1 RAs may affect ceramide metabolism by modulating the gut microbiota and altering the activity of ceramide synthase enzymes [

33]. However, ceramides are essential components of the skin’s outermost layer, where they help seal in moisture and defend against environmental stressors. When ceramide levels are depleted, whether due to systemic changes or medication effects, the skin barrier can become compromised, leading to dryness, irritation, and visible aging. Topical moisturizers enriched with ceramides can help restore these lipids and have been clinically shown to improve skin hydration, texture, and barrier function. In one study, a ceramide-containing cream significantly increased skin hydration within hours and outperformed placebo in reinforcing the skin barrier [

10]. For individuals undergoing GLP-1 RA therapy, incorporating a daily ceramide-rich moisturizer, along with gentle, pH-balanced cleansers, can help counteract medication-associated skin dryness and scaling. These products deliver key lipid components that support water retention and repair barrier integrity. Dermatologists also recommend applying moisturizers immediately after bathing to lock in moisture and using humidifiers in dry environments to minimize transepidermal water loss.

5.2. Incorporating antioxidants, such as Methylene Blue, in skincare routines:

In the skin, this relative mitochondrial lull induced by GLP1-RA treatment may accelerate cellular aging, reduce fibroblast function, and impair collagen synthesis and moisture retention. To counteract these mitochondrial and cellular effects, methylene blue (MB) has emerged as a promising intervention [

34].

MB is a well-established synthetic compound widely used in research and medicine [

1,

34]. It has a broad spectrum of biomedical applications due to its safety profile, redox properties, and cellular permeability. MB is FDA-approved for treating methemoglobinemia, a condition in which hemoglobin is oxidized and loses its ability to carry oxygen effectively. It is also routinely used as a surgical dye, assisting in identifying lymph nodes during breast cancer surgeries and helping to assess tissue viability or locate lesions during other procedures. In the neurological field, MB’s ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and support mitochondrial function has made it a candidate for treating neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Preclinical and clinical studies suggest MB may offer cognitive enhancement, memory improvement, and neuroprotection through its mitochondrial and antioxidant mechanisms. In oncology, MB is under investigation for its role in photodynamic therapy (PDT), where, upon light activation, it generates reactive oxygen species that selectively kill cancer cells. This selective cytotoxicity has been shown to enhance the efficacy of other therapeutic modalities.

It exhibits exceptional pharmacological properties, including high solubility in both water and lipids, which facilitates efficient skin penetration and delivery to intracellular targets, particularly the mitochondria [

34]. Importantly, MB functions as a potent redox-active molecule with a redox potential remarkably close to that of the endogenous antioxidants NADPH/NADP⁺, allowing it to shuttle electrons and effectively reduce oxidative stress [

34]. This property enables MB to bypass dysfunctional components of the electron transport chain, thereby supporting mitochondrial respiration and ATP production under stress conditions [

34].

Recent studies have indicated that MB acts as a potent mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, enhancing mitochondrial respiration, boosting ATP production, and reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

2]. These mechanisms are particularly relevant in the context of skin aging, where mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to oxidative damage, decreased extracellular matrix production, and impaired barrier function. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that low-dose MB treatment rejuvenates aged human fibroblasts by increasing proliferation and delaying cellular senescence [

2]. In 3D human skin equivalents, topical MB significantly increases dermal thickness, improves hydration, upregulates key extracellular matrix genes, including COL1A1 (collagen), COL3A1 (collagen), and ELN (elastin), and inhibits collagen-degrading matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [

2]. Early clinical testing of MB-containing topical formulations has shown improvements in skin elasticity, hydration, and a reduction in fine wrinkles. For patients concerned about accelerated skin aging related to GLP-1RA therapy, MB-based creams may offer a novel therapeutic approach. Although still an emerging therapy, MB’s ability to restore mitochondrial function, promote collagen and elastin synthesis, and enhance skin hydration makes it a compelling option for preserving skin health in the context of metabolic or pharmacological stressors.

5.3. How About Retinoids?

Retinoids (vitamin A derivatives like tretinoin and retinol) have long been the gold standard in dermatology for enhancing collagen synthesis and fighting wrinkles. They function by binding to nuclear receptors in skin cells, resulting in increased production of collagen and glycosaminoglycans while decreasing MMPs that degrade collagen and also speeding up epidermal cell turnover. Even milder retinoids (like retinol found in over-the-counter products) have demonstrated effectiveness: in a 12-week trial, applying 0.1% retinol led to significant increases in procollagen levels in the skin and a reduction in wrinkle depth. For patients experiencing heightened wrinkling, possibly due to weight loss, using a topical retinoid at night can be advantageous.

However, there may be a downside. Retinoids are well-known for accelerating skin cell turnover, which helps shed dead skin cells and promotes the growth of new, healthier cells. Increased skin turnover can deplete skin stem cells, reducing the regenerative capacity of the tissue. Since stem cells are crucial for repair and maintenance, their loss can lead to heightened skin sensitivity and irritation. Thus, retinoids can be irritating and may cause further dryness or flaking—a condition that must be managed, especially if the patient already has dry skin due to their GLP-1 RA regimen.

5.4. GLP-1 RA-Associated Hair Loss: Clinical Considerations and Management

Fortunately, hair loss associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists is often reversible. If the underlying mechanism is telogen effluvium, hair follicles are not destroyed but are simply in a resting phase. Once the acute trigger, usually rapid weight loss, resolves and the body re-equilibrates, hair density typically returns to normal within a few months.

Supportive treatments can accelerate regrowth. Ensuring sufficient protein intake is crucial, as hair is composed of keratin. Common micronutrient deficiencies, particularly biotin, iron, vitamin D, and zinc, should be assessed and addressed since they often contribute to hair shedding. Some dermatologists may recommend nutritional supplements or topical minoxidil based on observations of GLP-1–associated hair loss. In certain cases, a temporary dose reduction or pause in therapy to slow the pace of weight loss may promote hair recovery if clinically justified. Notably, among reported groups, most patients experiencing hair loss had undergone rapid or significant weight reduction, while those with more gradual weight loss reported fewer issues with alopecia. This underscores the importance of weight loss rate as a key modifiable factor. When telogen effluvium is suspected, reassurance is typically sufficient, as spontaneous regrowth is anticipated.

However, a scalp examination, or, in atypical cases, a biopsy, may be necessary to rule out other causes, such as androgenetic alopecia. This is especially relevant for women, as significant weight loss can lower estrogen levels, leading to a relative increase in androgen activity that may reveal female-pattern hair thinning in those who are predisposed.

6. Conclusion

While GLP-1 receptor agonists offer substantial systemic benefits, they may pose challenges to skin health, our largest and most visible organ. These dermatologic side effects, although often underrecognized, can significantly impact patients’ self-image and quality of life. However, with growing awareness and a proactive approach, these effects can be effectively managed. General measures such as proper hydration and balanced nutrition, along with targeted interventions, like ceramide-rich moisturizers, methylene blue-based antioxidants, and collagen stimulators, can help preserve skin integrity and appearance. Educating patients about potential changes in their skin allows for early intervention and empowers them to partner with healthcare providers in mitigating these effects. With attentive care, patients can continue benefiting from the metabolic advantages of GLP-1 RAs without compromising their skin’s health or youthful appearance. As we advance the therapeutic use of GLP-1 RAs, integrating skin care into the broader treatment strategy will enhance both clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Funding

Maryland Industrial Partnerships Program (MIPs).

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Kan Cao is the founder of Mblue Labs, a biotechnology company focused on skin health and aging. Mr. Amine Chaherli has no conflict of interest.

References

- Alfaris, N., et al., GLP-1 single, dual, and triple receptor agonists for treating type 2 diabetes and obesity: a narrative review. EClinicalMedicine, 2024. 75: p. 102782.

- Wilding, J.P.H., et al., Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med, 2021. 384(11): p. 989-1002.

- Mansour, M.R., et al., The rise of "Ozempic Face": Analyzing trends and treatment challenges associated with rapid facial weight loss induced by GLP-1 agonists. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg, 2024. 96: p. 225-227.

- Burke, O., et al., Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist medications and hair loss: A retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2025. 92(5): p. 1141-1143.

- Drucker, D.J., Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Application of Glucagon-like Peptide-1. Cell Metab, 2018. 27(4): p. 740-756.

- Moiz, A., et al., Mechanisms of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist-Induced Weight Loss: A Review of Central and Peripheral Pathways in Appetite and Energy Regulation. Am J Med, 2025. 138(6): p. 934-940.

- Ferhatbegovic, L., D. Mrsic, and A. Macic-Dzankovic, The benefits of GLP1 receptors in cardiovascular diseases. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc, 2023. 4: p. 1293926.

- Tofe, S., et al., Real-world GLP-1 RA therapy in type 2 diabetes: A long-term effectiveness observational study. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab, 2019. 2(1): p. e00051.

- Patino, W., et al., A Review of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 in Dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol, 2025. 18(3): p. 42-50.

- Light, D., et al., Effect of weight loss after bariatric surgery on skin and the extracellular matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2010. 125(1): p. 343-351.

- Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J., et al., Extracellular Matrix Remodeling of Adipose Tissue in Obesity and Metabolic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20(19).

- Sakers, A., et al., Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell, 2022. 185(3): p. 419-446.

- Rocha, R.I., et al., Skin Changes Due to Massive Weight Loss: Histological Changes and the Causes of the Limited Results of Contouring Surgeries. Obes Surg, 2021. 31(4): p. 1505-1513.

- Gorgojo-Martinez, J.J., et al., Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. J Clin Med, 2022. 12(1).

- Dumas, S.N. and J.M. Ntambi, A Discussion on the Relationship between Skin Lipid Metabolism and Whole-Body Glucose and Lipid Metabolism: Systematic Review. J Cell Signal (Los Angel), 2018. 3(3).

- Manzoni, A.P. and M.B. Weber, Skin changes after bariatric surgery. An Bras Dermatol, 2015. 90(2): p. 157-66.

- Desai, D.D., et al., GLP-1 agonists and hair loss: a call for further investigation. Int J Dermatol, 2024. 63(9): p. 1128-1130.

- Kang, D.H., et al., Telogen Effluvium Associated With Weight Loss: A Single Center Retrospective Study. Ann Dermatol, 2024. 36(6): p. 384-388.

- Persson, C., A. Eaton, and H.N. Mayrovitz, A Closer Look at the Dermatological Profile of GLP-1 Agonists. Diseases, 2025. 13(5).

- Paschou, I.A., et al., The effects of GLP-1RA on inflammatory skin diseases: A comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2025.

- Park, K., Role of micronutrients in skin health and function. Biomol Ther (Seoul), 2015. 23(3): p. 207-17.

- Nijenhuis-Noort, E.C., et al., The Fascinating Interplay between Growth Hormone, Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1, and Insulin. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul), 2024. 39(1): p. 83-89.

- Haines, M.S., Endocrine complications of anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord, 2023. 11(1): p. 24.

- Watabe, R., et al., Leptin controls hair follicle cycling. Exp Dermatol, 2014. 23(4): p. 228-9.

- Dopytalska, K., et al., The role of leptin in selected skin diseases. Lipids Health Dis, 2020. 19(1): p. 215.

- Trevor, L.V., et al., Adipose Tissue: A Source of Stem Cells with Potential for Regenerative Therapies for Wound Healing. J Clin Med, 2020. 9(7).

- Xiong, Z.M., et al., Methylene blue alleviates nuclear and mitochondrial abnormalities in progeria. Aging Cell, 2016. 15(2): p. 279-90.

- Lanza, I.R., et al., Chronic caloric restriction preserves mitochondrial function in senescence without increasing mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab, 2012. 16(6): p. 777-88.

- Breininger, S.P., et al., Effects of obesity and weight loss on mitochondrial structure and function and implications for colorectal cancer risk. Proc Nutr Soc, 2019. 78(3): p. 426-437.

- Wani, M., et al., Unveiling Skin Manifestations: Exploring Cutaneous Signs of Malnutrition in Eating Disorders. Cureus, 2023. 15(9): p. e44759.

- Sinha, R.A., et al., Thyroid hormone induction of mitochondrial activity is coupled to mitophagy via ROS-AMPK-ULK1 signaling. Autophagy, 2015. 11(8): p. 1341-57.

- Lin, K., et al., Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist regulates fat browning by altering the gut microbiota and ceramide metabolism. MedComm (2020), 2023. 4(6): p. e416.

- Wretlind, A., et al., Ceramides are decreased after liraglutide treatment in people with type 2 diabetes: a post hoc analysis of two randomized clinical trials. Lipids Health Dis, 2023. 22(1): p. 160.

- Xue, H., A. Thaivalappil, and K. Cao, The Potentials of Methylene Blue as an Anti-Aging Drug. Cells, 2021. 10(12).

- Xiong, Z.M., et al., Ultraviolet radiation protection potentials of Methylene Blue for human skin and coral reef health. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 10871.

- Xiong, Z.M., et al., Anti-Aging Potentials of Methylene Blue for Human Skin Longevity. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 2475.

- Mukherjee, S., et al., Retinoids in the treatment of skin aging: an overview of clinical efficacy and safety. Clin Interv Aging, 2006. 1(4): p. 327-48.

- Kong, R., et al., A comparative study of the effects of retinol and retinoic acid on histological, molecular, and clinical properties of human skin. J Cosmet Dermatol, 2016. 15(1): p. 49-57.

- Ojeh, N., et al., Stem Cells in Skin Regeneration, Wound Healing, and Their Clinical Applications. Int J Mol Sci, 2015. 16(10): p. 25476-501.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).