Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

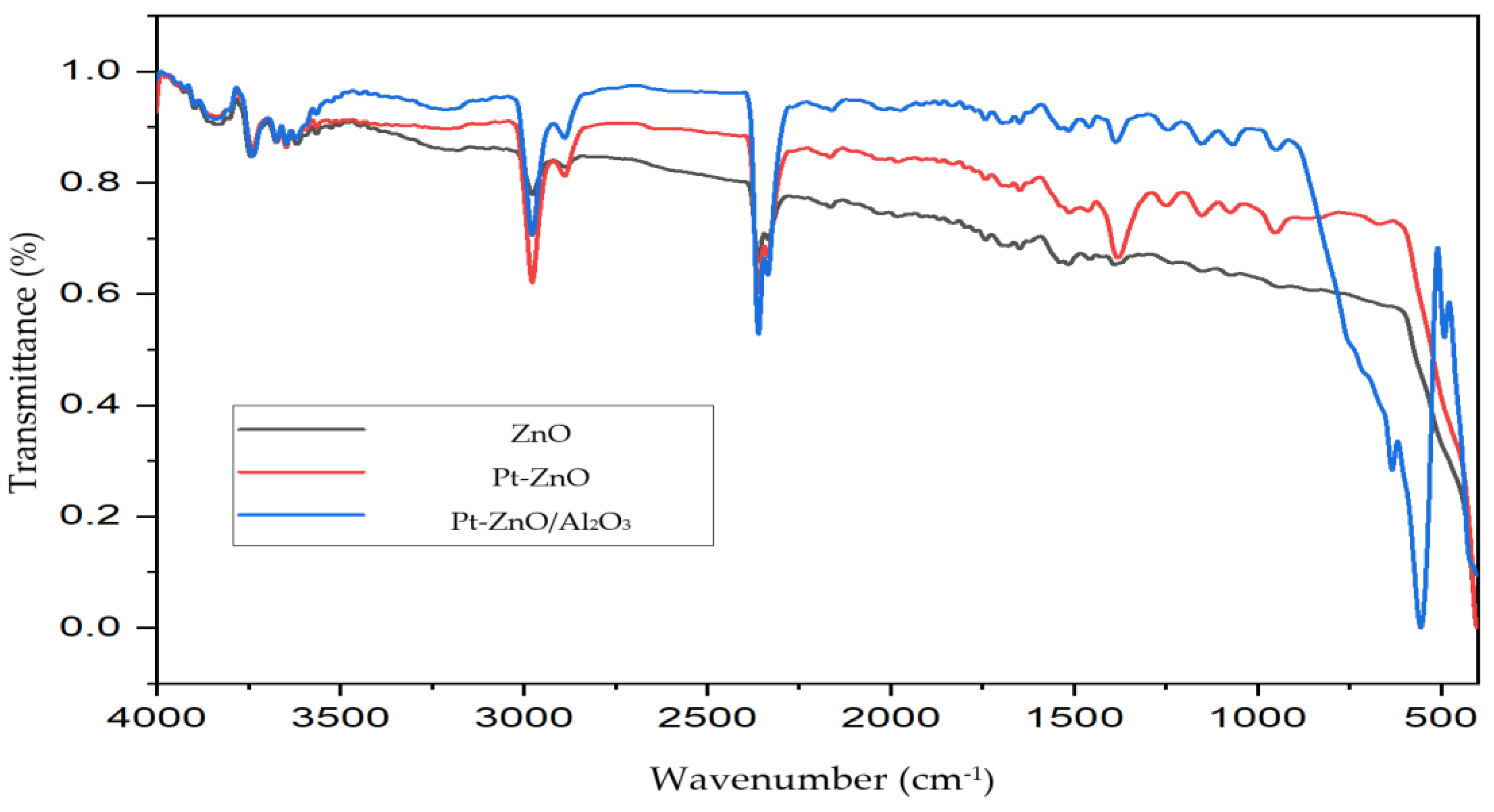

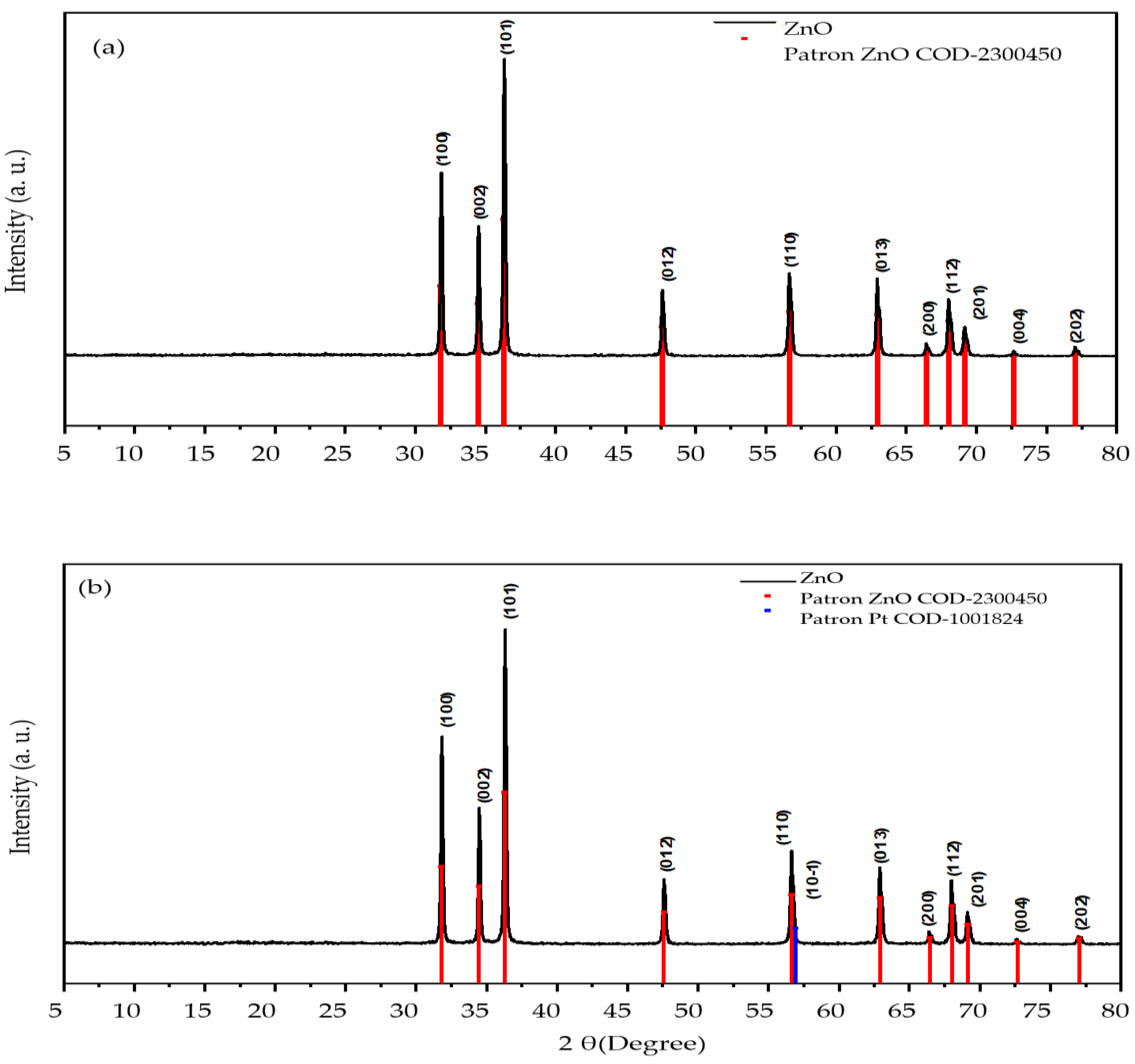

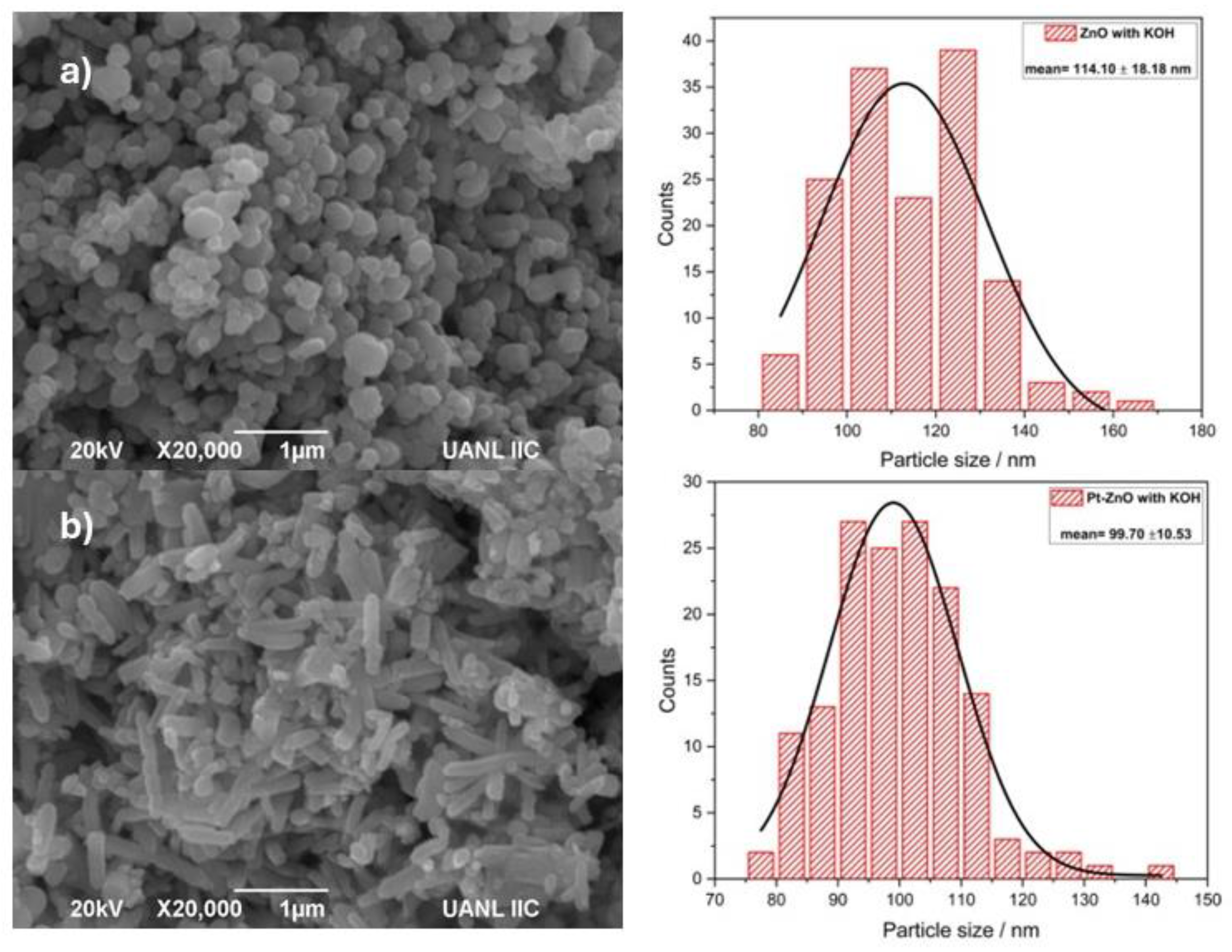

2.1. Photocatalyst Characterization

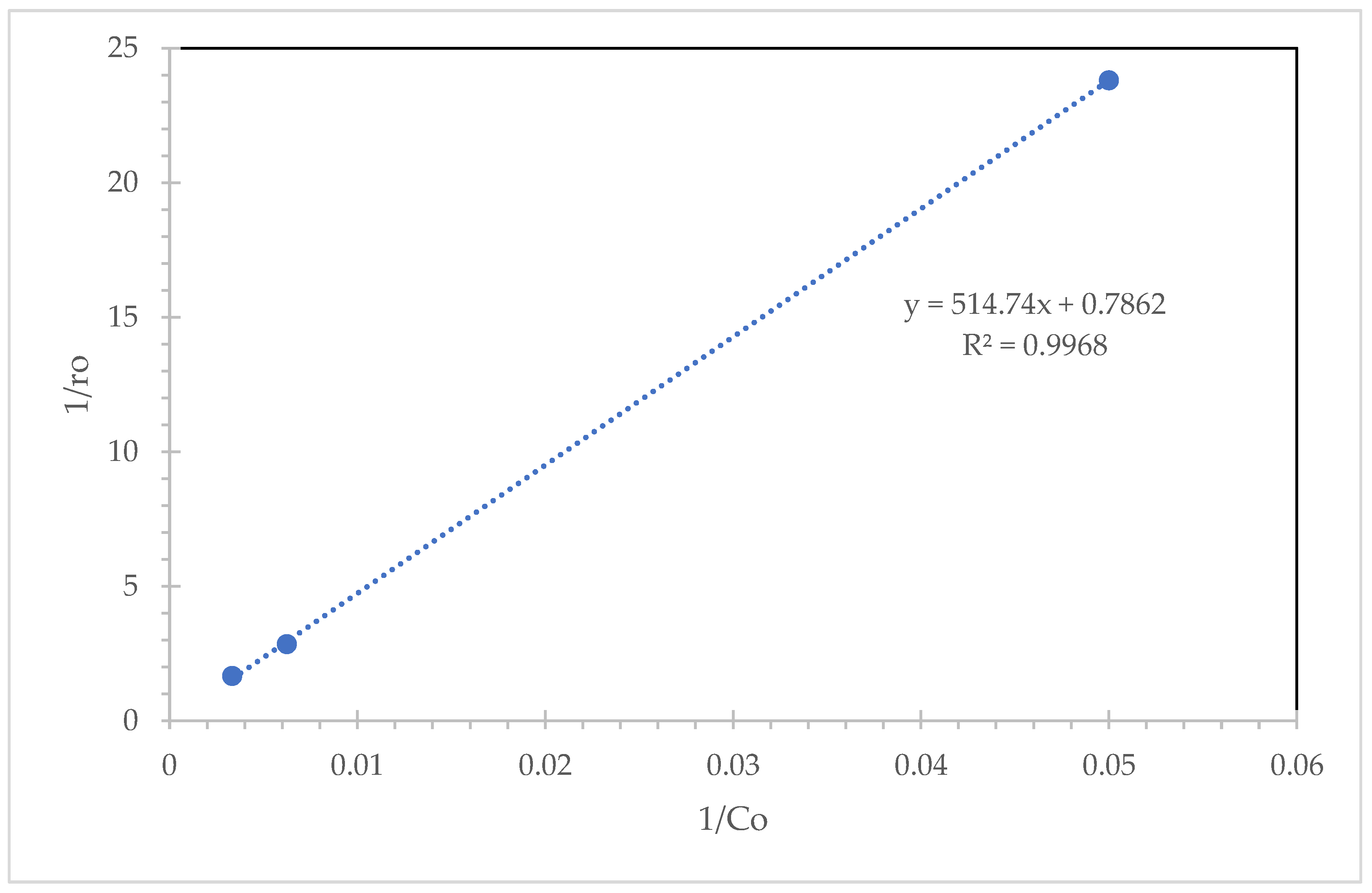

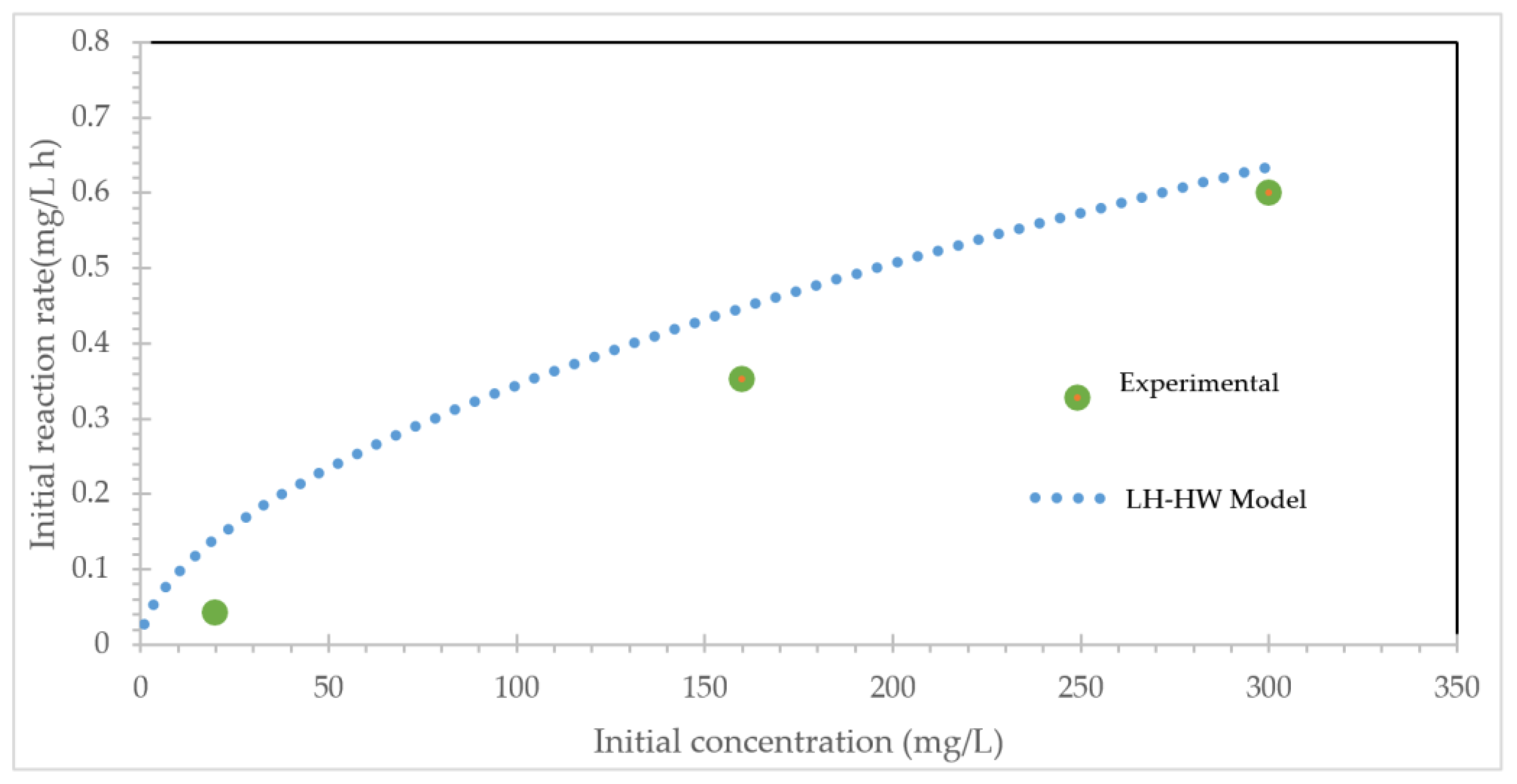

2.2. Kinetic Analysis

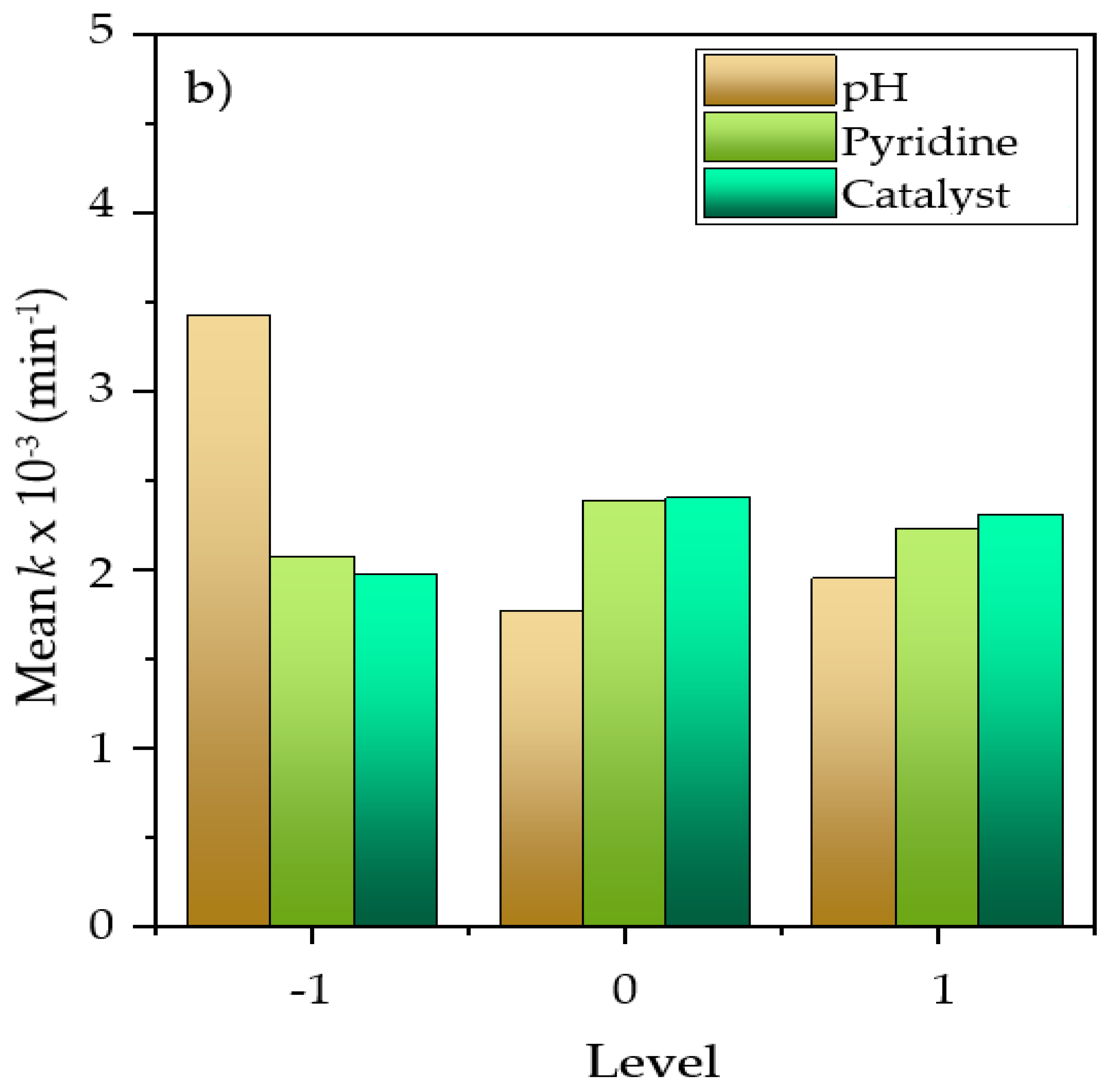

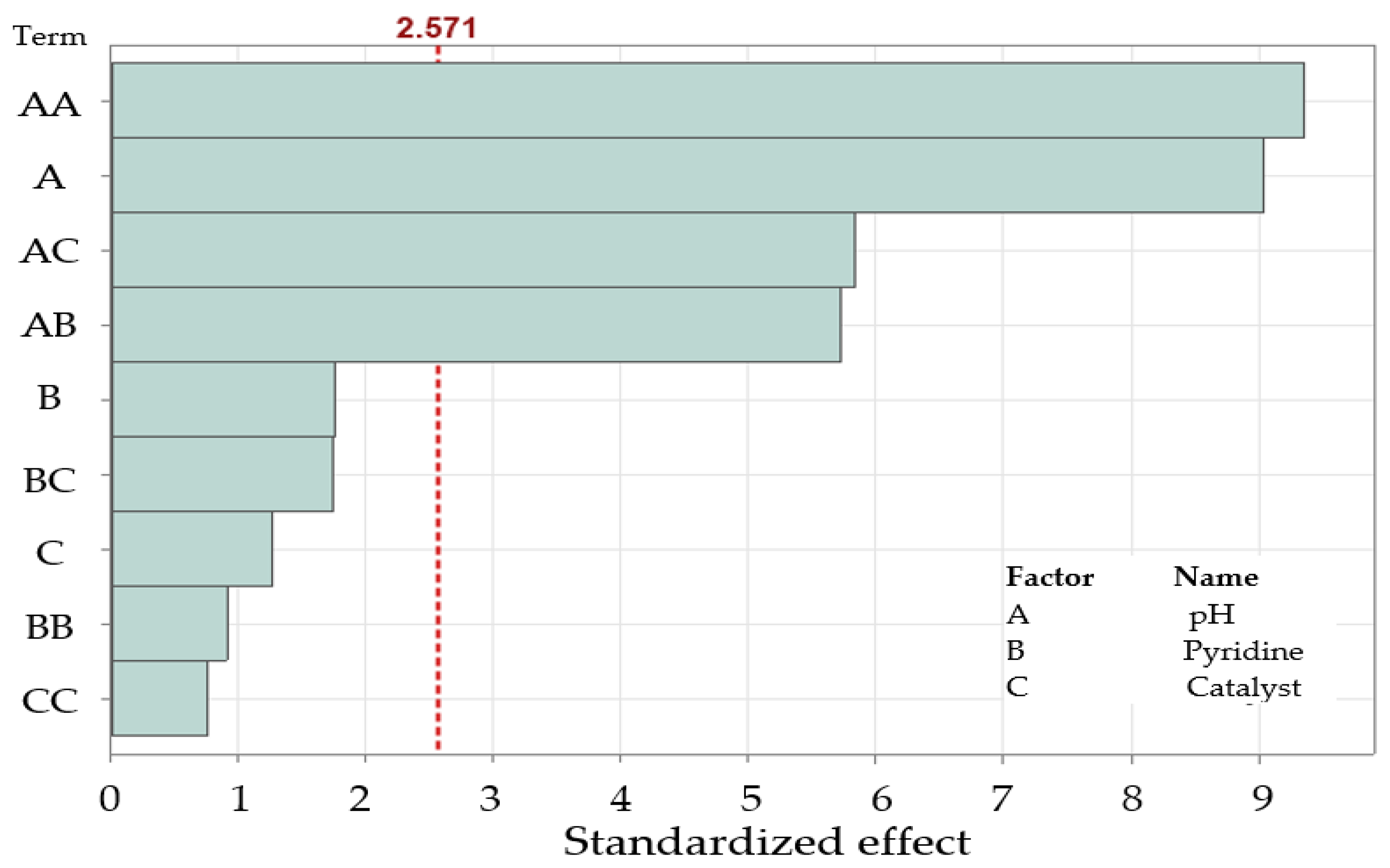

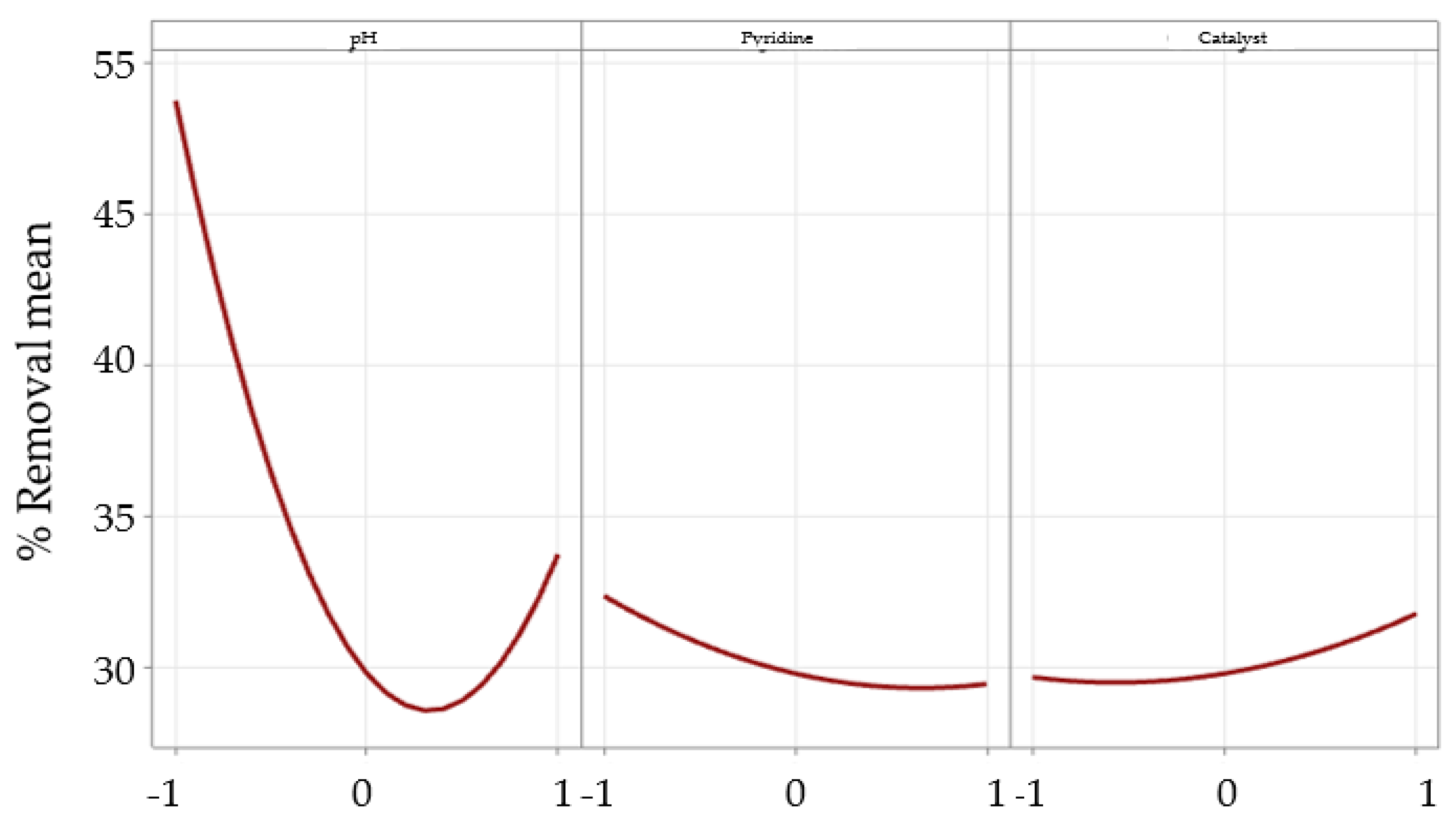

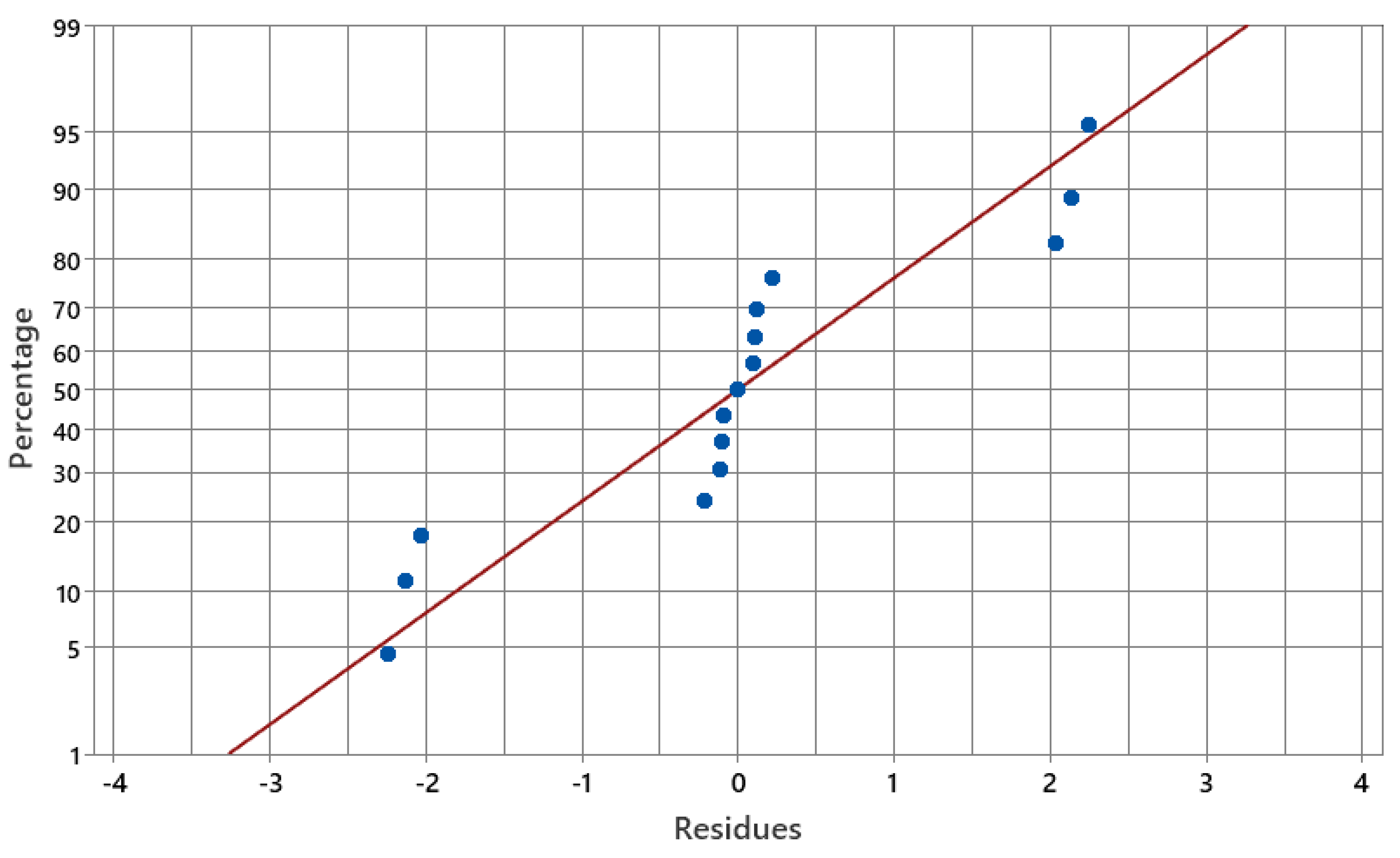

2.3. Evaluation of Critical Variables in Pyridine Removal by DOE

3. Methodology

3.1. Chemical Products and Reagents

3.2. Photocatalyst Preparation

3.3. Photocatalyst Characterization

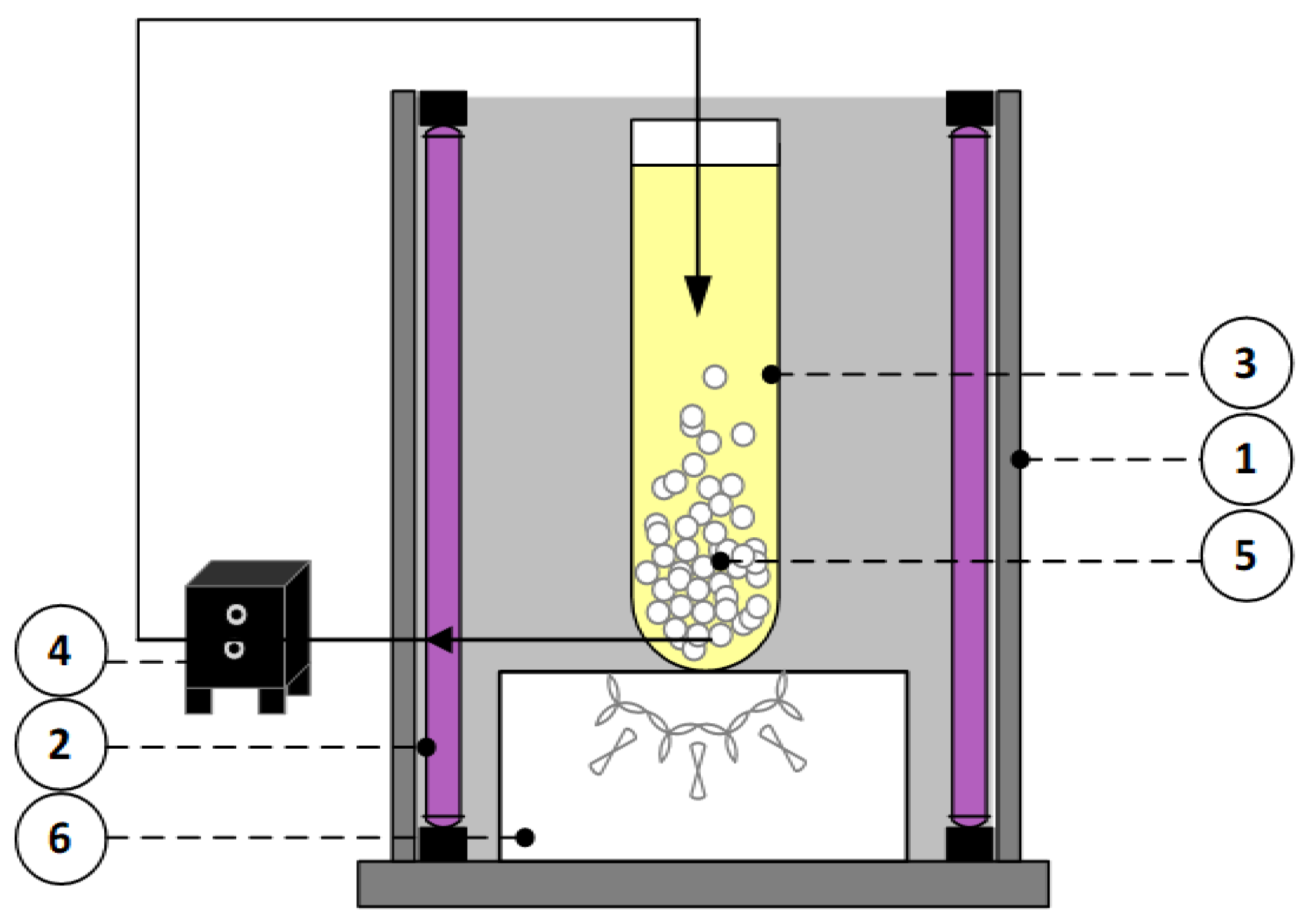

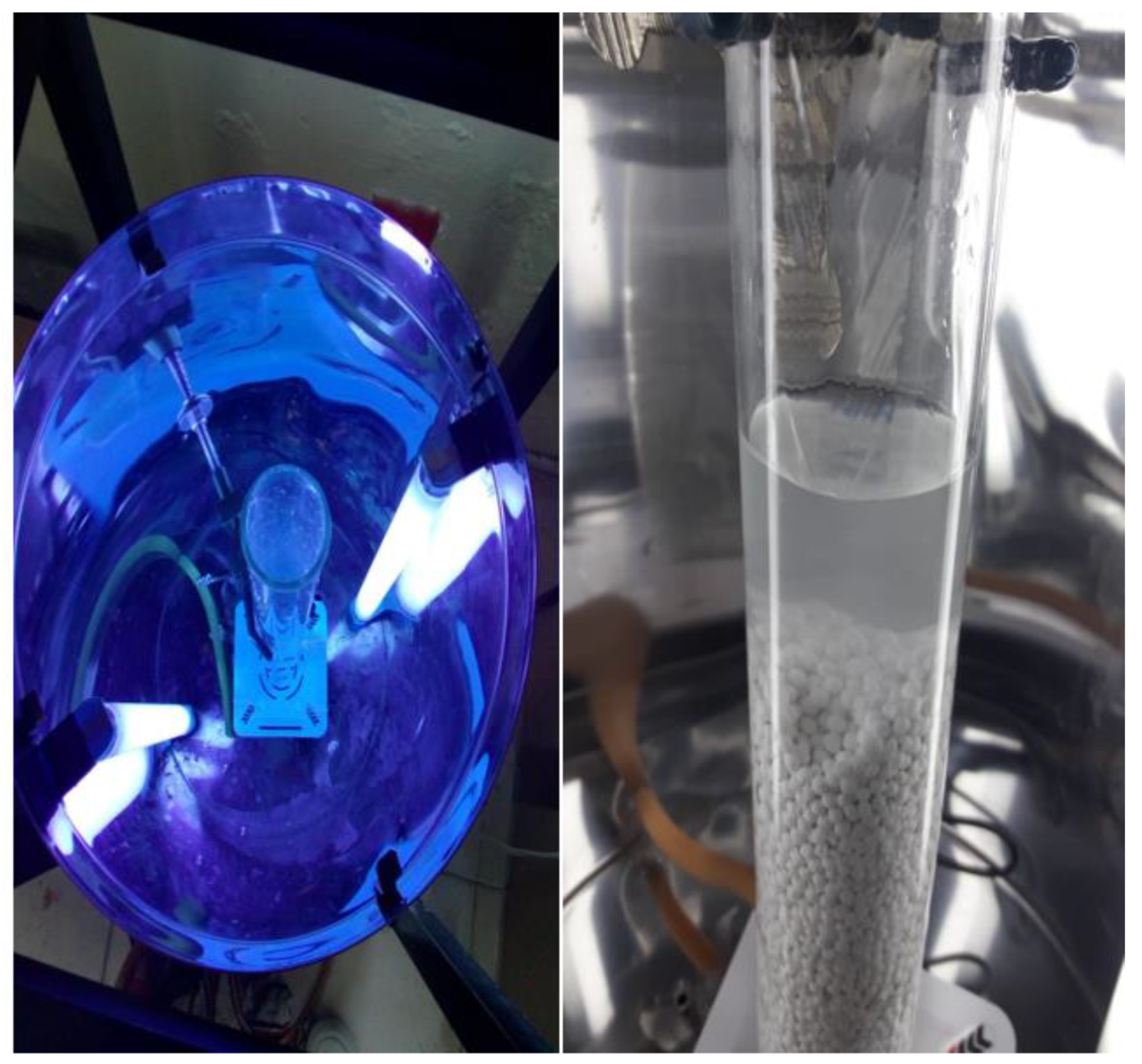

3.4. Fluidized Bed Photocatalytic Reactor Used for Photocatalytic Experiments

3.5. Photocatalytic Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rajput, M.S.; Mishra, B. Biodegradation of pyridine raffinate using bacterial laccase isolated from garden soil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 17, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, A.K.; Sahoo, A.; Jena, H.M.; Patra, H. Industrial wastewater treatment by Aerobic Inverse Fluidized Bed Biofilm Reactors (AIFBBRs): A review. J. Water Process. Eng. 2018, 23, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, D.; Sreekanth, P.R.; Behera, P.K.; Pradhan, M.K.; Patnaik, A.; Salunkhe, S.; Cep, R. Advances in synthesis, medicinal properties and biomedical applications of pyridine derivatives: A comprehensive review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wang, C.; Yin, H.; Zhang, S.; Qin, S.; Liu, W.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Yang, C. Enhancement of the quinoline separation from pyridine: Study on competitive adsorption kinetics in foam fractionation with salt. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 359, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Qadir, T.; Sharma, P.K.; Jeelani, I.; Abe, H. A Review on The Medicinal And Industrial Applications of N-Containing Heterocycles. Open Med. Chem. J. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, Y.; Rittmann, B.E. Bioavailable electron donors leached from leaves accelerate biodegradation of pyridine and quinoline. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 654, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Geng, W.-C.; Jiang, H.; Wu, B. Recent advances in biocatalysis of nitrogen-containing heterocycles. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 54, 107813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Yu, S.; Wang, J. Degradation of pyridine and quinoline in aqueous solution by gamma radiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2018, 144, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalat, O.; Elsayed, M. A study on microwave removal of pyridine from wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, C. , et al., Fluidized bed photoreactor for the removal of acetaminophen and pyridine using Al-doped TiO2 supported on alumina. Iranian Journal of Catalysis, 2022. 12(3).

- Program, N.T. , NTP technical report on the toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of pyridine (CAS no. 110-86-1) in F344/N rats, Wistar rats, and B6C3F1 mice (drinking water studies). 2000.

- Goswami, S. , et al., Recent trends in the synthesis, characterization and commercial applications of zinc oxide nanoparticles-a review. Inorganica Chimica Acta, 2024: p. 122350.

- Tarannum, N. and D. Kumar, Pyridine: Exposure, risk management, and impact on life and environment, in Hazardous Chemicals. 2025, Elsevier. p. 363-374.

- Khan, K.M., S. S. Gillani, and F. Saleem, Role of pyridines as enzyme inhibitors in medicinal chemistry, in Recent Developments in the Synthesis and Applications of Pyridines. 2023, Elsevier. p. 207-252.

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, X.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, L.; Shen, X. Biodegradation: the best solution to the world problem of discarded polymers. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M., et al., Environmental issues: a challenge for wastewater treatment. Green materials for wastewater treatment, 2020: p. 1-12.

- Jaramillo-Páez, C.; Navío, J.; Hidalgo, M.; Macías, M. ZnO and Pt-ZnO photocatalysts: Characterization and photocatalytic activity assessing by means of three substrates. Catal. Today 2018, 313, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gines-Palestino, R., E. Oropeza-De la Rosa, C. Montalvo-Romero, and D. Cantú-Lozano, Rheokinetic and effectiveness during the phenol removal in mescal vinasses with a rotary disks photocatalytic reactor (RDPR) Reocinética y efectividad durante la remoción de fenol en vinazas de mezcal con un reactor fotocatalítico de discos rotativos (RDPR).

- López- Ojeda, G.C. , et al., Oxidación fotoelectrocatalítica de fenol y de 4-clorofenol con un soporte de titanio impregnado con TiO2. Revista internacional de contaminación ambiental, 2011. 27(1): p. 75-84.

- Jing, Y.; Yin, H.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, S.; Liu, H.; Xie, L.; Lei, Q.; Sun, M.; Yu, S. Fabrication of Pt doped TiO2–ZnO@ZIF-8 core@shell photocatalyst with enhanced activity for phenol degradation. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M., I. Das, M.M. Ghangrekar, and L. Blaney, Advanced oxidation processes: Performance, advantages, and scale-up of emerging technologies. Journal of environmental management, 2022. 316: p. 115295.

- Deng, Y.; Zhao, R. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) in Wastewater Treatment. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2015, 1, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibigbami, B.T.; Adewuyi, S.O.; Akinsorotan, A.M.; Sobowale, A.A.; Odoh, I.M.; Aladetuyi, A.; Mohammed, S.E.; Nelana, S.M.; Ayanda, O.S. Advanced oxidation processes: a supplementary treatment option for recalcitrant organic pollutants in Abattoir wastewater. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2023, 21, 1019–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, X., W. F. Jardim, and M.I. Litter, Procesos avanzados de oxidación para la eliminación de contaminantes. Eliminación de contaminantes por fotocatálisis heterogénea, 2001. 2016: p. 3-26.

- Bello, M.M.; Raman, A.A.A.; Purushothaman, M. Applications of fluidized bed reactors in wastewater treatment – A review of the major design and operational parameters. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1492–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, E.E.S. , Heat and mass transfer in particulate suspensions. 2013.

- Cai, Q., B. Lee, S. Ong, and J. Hu, Fluidized-bed Fenton technologies for recalcitrant industrial wastewater treatment–Recent advances, challenges and perspective. Water Research, 2021. 190: p. 116692.

- An, Q.; Li, J.; Peng, J.; Hu, L. Dissolved gas analysis in transformer oil using Pd, Pt doped ZnO: A DFT study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2025, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubha, J.; Roopashree, B.; Patil, R.; Khan, M.; Shaik, M.R.; Alaqarbeh, M.; Alwarthan, A.; Karami, A.M.; Adil, S.F. Facile synthesis of ZnO/CuO/Eu heterostructure photocatalyst for the degradation of industrial effluent. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Preparations and applications of zinc oxide based photocatalytic materials. Adv. Sens. Energy Mater. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatou, M.-A.; Lagopati, N.; Vagena, I.-A.; Gazouli, M.; Pavlatou, E.A. ZnO Nanoparticles from Different Precursors and Their Photocatalytic Potential for Biomedical Use. Nanomaterials 2022, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güell, F.; Galdámez-Martínez, A.; Martínez-Alanis, P.R.; Catto, A.C.; da Silva, L.F.; Mastelaro, V.R.; Santana, G.; Dutt, A. ZnO-based nanomaterials approach for photocatalytic and sensing applications: recent progress and trends. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 3685–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Dhal, G. Property and structure of various platinum catalysts for low-temperature carbon monoxide oxidations. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, P.; Cheng, K.; Hua, X.; Xie, M.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pi, C.; Zhang, S. Structural Regulation of Advanced Platinum-Based Core-Shell Catalysts for Fuel Cell Electrocatalysis. Minerals 2025, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marturano, M.; Aglietti, E.; Ferretti, O. α-Al2O3 Catalyst supports for synthesis gas production: influence of different alumina bonding agents on support and catalyst properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1997, 47, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hua, M.; Zhou, S.; Hu, D.; Liu, F.; Cheng, H.; Wu, P.; Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Zhu, W. Regulating the coordination environment of surface alumina on NiMo/Al2O3 to enhance ultra-deep hydrodesulfurization of diesel. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2024, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K. , et al., Platinum-tin nano-catalysts supported on alumina for direct dehydrogenation of n-butane. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 2015. 15(10): p. 8305-8310.

- Huang, X.; Li, X.; Deng, C.; Deng, X.; Qu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, S.; Du, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; et al. Fabrication of highly efficient ZnO-Pt catalysts assisted by biomass-derived carboxymethyl cellulose for the photodegradation of diverse antibiotics. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 382, 125418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Kandori, K.; Nakayama, T. Synthesis of layered zinc hydroxide chlorides in the presence of Al(III). J. Solid State Chem. 2006, 179, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Liu, L.; He, R. Pt/TiO2-ZnO in a circuit Photo-electro-catalytically removed HCHO for outstanding indoor air purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 206, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Vera, O.F., J. J. Mutiz, and J. Urresta Aragón, Synthesis and characterization of Cu type catalysts supported on MgO, SiO 2, ZnO, and Al 2 O 3 applied to the hydrogenolysis of glycerol. Revista ION, 2017. 30(2): p. 31-41.

- Manikandan, B., K. Murali, and R. John, Optical, morphological and microstructural investigation of TiO2 nanoparticles for photocatalytic application. Iranian Journal of Catalysis, 2021. 11(1).

- Manikandan, A., J. J. Vijaya, L.J. Kennedy, and M. Bououdina, Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Zn1− xCuxFe2O4 nanoparticles prepared by microwave combustion method. Journal of molecular structure, 2013. 1035: p. 332-340.

- Gines-Palestino, R.S. , et al., Microstructural, Morphological, and Optical Study of Synthesis of ZnO and Pt ZnO Nanoparticles by a Simple Method Using Different Precipitating Agents. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 2024. 35(1): p. e-20230092.

- Hong, D.; Cao, G.; Zhang, X.; Qu, J.; Deng, Y.; Liang, H.; Tang, J. Construction of a Pt-modified chestnut-shell-like ZnO photocatalyst for high-efficiency photochemical water splitting. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 283, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkoç, H. and Ü. Özgür, Zinc oxide: fundamentals, materials and device technology. 2008: John Wiley & Sons.

- Moctezuma, E. , López M. , Zermeño B. Reaction pathways for the photocatalytic degradation of phenol under different experimental conditions. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Química. 2016, 15, 1,129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo, C. , Aguilar, C., Alcoser, R., et al. Semi-Pilot Photocatalytic Rotating Reactor (RFR) with Supported TiO2/Ag Catalysts for Water Treatment. Molecules, 2018, 23(1), 224. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6017124/.

- Fogler, H.S. Elements of Chemical Reaction Engineering, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Hongkong, China, 1999; ISBN 9780135317167. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, R.W.; McEvoy, S.R. Photocatalytic degradation of phenol in the presence of near-UV illuminated titanium dioxide. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 1992, 64, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva Elisa, Montalvo Carlos, Moctezuma Edgar * and Leyva Socorro. Photocatalytic degradation of pyridine in water solution using ZnO as an alternative catalyst to TiO2. J. Ceramic Processing Res. 2008, 9, 455–462.

- Shu, J.; Ren, B.; Zhang, W.; Wang, A.; Lu, S.; Liu, S. Influencing Factors and Kinetics of Modified Shell Powder/La-Fe-TiO2 Photocatalytic Degradation of Pyridine Wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 14835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensalah, N.; Ahmad, M.I.; Bedoui, A. Catalytic Degradation of 4-Ethylpyridine in Water by Heterogeneous Photo-Fenton Process. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosu, V.; Arora, S.; Subbaramaiah, V. Simultaneous degradation of nitrogenous heterocyclic compounds by catalytic wet-peroxidation process using box-behnken design. Environ. Eng. Res. 2019, 25, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Hussian, S. An Efficient Activated Carbon for the Wastewater Treatment, Prepared from Peanut Shell. Mod. Res. Catal. 2013, 02, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador-Gómez, L.P. , et al., Synthesis, Modification, and Characterization of Fe3O4@ SiO2-PEI-Dextranase Nanoparticles for Enzymatic Degradation of Dextran in Fermented Mash. Processes, 2022. 11(1): p. 70.

| Experiments | Coded variables | Natural variables | ||||

|

pH ( - ) |

Concentration (ppm) |

Time (min) |

pH ( - ) |

Concentration (ppm) |

Time (min) |

|

| 1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 3 | 160 | 120 |

| 2 | -1 | -1 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 240 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 160 | 240 |

| 4 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 6 | 20 | 120 |

| 5 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 160 | 360 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 160 | 240 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 160 | 360 |

| 8 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 300 | 240 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 9 | 160 | 120 |

| 10 | 0 | -1 | 1 | 6 | 20 | 360 |

| 11 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 9 | 20 | 240 |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 300 | 360 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 160 | 240 |

| 14 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 6 | 300 | 120 |

| 15 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 300 | 240 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).