1. Introduction

The global switch to renewable energy has driven a rapid increase in solar photovoltaic (PV) systems as a clean and sustainable alternative to conventional power generation. Governments and industries are heavily investing in solar power, particularly to achieve reduced carbon emissions, enhance energy security, and diversify power generation portfolios. However, despite these advantages, it creates substantial challenges with respect to grid stability and reliable operation owing to its inherently intermittent and uncertain nature. Beyond that, such renewable energy sources are integrated with the conventional baseload source, as in the case of thermal or hydro alongside solar PV, which causes complexity in grid balancing. This difference in behavior causes frequent changes to complicate the load-frequency control and increase risk for the power system. Even small generation-demand imbalances can bring safety consequences, power supply interruption, and damage to infrastructure.

The power system needs to operate securely by maintaining system frequency at specific, predetermined ranges. The traditional load frequency control (LFC) systems lack the ability to handle the unexpected rapid changes that solar photovoltaic (PV) generation produces. Real-time imbalances occur because of sudden PV output changes that result from both cloud cover and intense sunlight. The high reliability of thermal plants makes them unsuitable for immediate remedial actions because they respond slowly. PID controllers have a delayed response to frequency deviations and generate slow control actions that are ineffective during dynamic situations.

Advanced control strategies address these challenges through the integration of precise forecasting with adaptive real-time dispatch systems. The prediction of solar generation and load demand in short-term periods becomes accurate through the implementation of machine learning models, including Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. The forecasts allow grid operators to predict system changes so they can actively control operations, especially during scheduling and battery energy storage system (BESS) dispatch.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) provides better performance than traditional PID controllers because it optimizes control actions through continuous predictions of system behavior. The predictive functionality improves both system responsiveness and frequency regulation precision. The integration of forecasting models with predictive control into a unified framework needs further investigation in current research.

The paper attempts to fill that gap by proposing a unified framework that integrates forecasting based on SVR, battery dispatch inspired by MPC, and PID control via Differential Evolution (DE). The framework is implemented in a two-area hybrid power system having solar and thermal generation sources to improve frequency stability with renewable intermittency.

Key contributions of this work include:

The SVR models facilitate short-term forecasts of solar generation and synthetic load demand, permitting proactive control decisions.

A real-time MPC-inspired battery dispatch has been implemented, which utilizes SVR predictions for achieving adaptive energy balancing.

Differential Evolution-optimized PID tuning implementation improves frequency regulation by yielding improved dynamic response and less overshoot.

The integrated control framework combines several elements into a modular structure that offers superior performance for future hybrid power systems with high penetrations of renewables while enhancing grid resilience and frequency stability under varying operating conditions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction to Load Frequency Control and Its Importance

Load frequency control (LFC) plays an important role in ensuring the stability and reliability of the power systems. The main objective is to effectively balance the production and consumption of electricity in the system as close as possible to its nominal value of frequency, typically 50 Hz for countries such as India and many parts of Europe and 60 Hz for North America. When power systems that are interconnected experience sudden changes in load, these frequency deviations can persist, potentially leading to instability, equipment damage, or even widespread blackouts. LFC works as a real-time regulator, continuously adjusting generation to match demand and maintaining frequency within safe limits, which is essential for the healthy and secure operation of the grid [

1,

2,

3]. Load Frequency Control, or LFC, is one of the most crucial parts of managing power flow between control areas, and it ensures each area operates within the limits governed by its power performance agreements [

4]. Frequency stability is an important aspect in power system operations. Any imbalance between electricity generation and consumption leads to frequency deviations—either above or below the nominal level. However, when demand exceeds generation, frequencies fall in the system; such a condition creates a strain on generators and makes the entire system less efficient. On the contrary, if production exceeds demand, the frequency increases and may damage equipment. Deviations beyond threshold levels, typically ±0.5 Hz from the nominal frequency, generally lead to energy wastage and pose a serious risk to sensitive electrical devices. In such instances, protective relays are designed to trip or isolate part of the grid from the rest, thereby avoiding cascading failures and very large-scale blackouts in the system [

5,

6]. Uncontrolled frequency deviations are implicated in several real-world incidents. Perhaps the largest blackout in history dating back to July 2012 was the Indian blackout, terminating the power supply of over 620 million people with frequency instability brought on by adverse loading and poor frequency regulation [

7]. Another real-world incident, the Texas Power Crisis of February 2021, evidenced frequency deviations that littered its causal path with rolling blackouts—all because the power plants failed to step up to the plate during periods of super-high demand and extreme weather conditions [

8]. Traditional load-frequency control (LFC) methods have significantly depended on proportional, integral, and derivative (PID) controllers and governor-based mechanisms to maintain system frequency. They were probably effective in earlier, more determined grids but fail to meet the conditions of modern power systems, especially with high penetration from renewable energy sources [

9]. Conventional load frequency control systems are characterized by a slow response to sudden changes in load, which results in partial or complete frequency instability due to delayed corrective action [

10,

11,

12]. PID controllers in this type of system operate with fixed gain parameters—Kp, Ki, and Kd, for example—making them difficult to adapt to the realities of a dynamic grid. Their inflexibility makes them less efficient in fast-changing operational conditions [

13]. Also, the old LFC systems were simply not designed to account for the intermittency and variability of renewable sources such as solar and wind. These older frequency control methods cannot guarantee stable operation as the penetration of renewables increases and generator reserves become reduced [

14]. Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) store surplus energy during peak generation periods and discharge during deficits, thus providing an excellent solution for frequency control. Traditional LFC methods, however, do not utilize battery dispatch strategies, thus limiting their positive role in enhancing grid stability through energy storage [

15]. Recent advances have shown the need for more adaptive control strategies. Studies have proposed AI-driven controllers, multilayer intelligent systems, and Model Predictive Control (MPC) schemes that significantly enhance frequency regulation in high-renewable-integration systems [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. These developments reinforce the pressing need to evolve LFC mechanisms that accommodate the dynamic and stochastic nature of modern power grids.

2.2. Conventional Load Frequency Control (LFC)Methods and Their Limitations

2.2.1. PID Controllers (Proportional-Integral-Derivative)

The primary goal of Load Frequency Control (LFC) is to balance the input and output energies in the electric system so that the frequency remains within its limits. The PID controllers were the solution in these models because they were simple, reliable, and straightforward to implement. Increasing incorporation of renewable systems, including solar and wind, brings forth drawbacks in such PID-based load frequency control. Probably, the most important disadvantage is found in their reactive behavior when it comes to mode: they only react to a frequency deviation but do not anticipate or proactively address behavior changes in the system. This reactive property exacerbates the problem in hybrid systems, where renewability leads to rapid and unpredictable fluctuations. Another major limitation exists in static PID tuning. Standard PID controllers operate with fixed gains that do not change according to variations in the dynamics of the system, thus impairing their performance in highly renewable-rich environments, where power output is highly nonlinear and stochastic. As a result, frequency recovery may be languid sometimes to the detriment of system stability [

22,

23,

24].

Studies on multi-area interconnected hybrid systems have also confirmed that utilization of the PID control alone is inadequate to guarantee robust frequency and voltage regulation under renewable variability [

25]. These drawbacks have led to heightened interest in more advanced control techniques—fuzzy logic, Model Predictive Control (MPC), and artificial intelligence-based methods—that possess better adaptability and predictive ability to fulfill the needs of modern power grid operation [

26,

27].

2.2.1. Fuzzy Logic-Based PID Controllers (Fuzzy-PID)

Fuzzy-PID controllers are an extension of conventional PID control that integrates fuzzy logic to adjust the controller gains automatically in real time. This feature allows these systems to be capable of addressing nonlinearities and uncertainties, which characterize most modern power systems—the most critical being those with extremely high renewable energy penetration. In contrast to the conventional PID controllers that work with fixed tuning parameters, the fuzzy-PID controllers continuously adapt their proportional, integral, and derivative gain tuning to the current operating conditions of the system. Because this tuning is done in real time, it can be presumed to be effective in handling the full variability and intermittency realized with solar PV and wind energy sources.

However, fuzzy-PID controllers are reactive since they operate only after there has been a frequency deviation. They can neither foresee nor predict any future state of the system. In rapidly changing conditions, such as sudden drops in solar output due to cloud coverage, the performance of Fuzzy-PID may degrade, and therefore they are not good candidates for large-scale applications in hybrid grids. These controllers, barring an inherent predictive mechanism, lag in performance to advanced concepts such as Model Predictive Control (MPC), which makes control decisions by pre-emptively incorporating future trends. Accordingly, there is a consequent rise in AI-based forecasting and control methods, offering more amenable prediction-based regulatory strategies for enhancing grid resilience in renewable environments [

28,

29,

30].

2.2.2. Model Predictive Control (MPC) for LFC

Model Predictive Control (MPC) is a forward-looking, optimization-based control strategy that addresses key limitations of traditional PID and Fuzzy-PID controllers in modern power systems. Unlike reactive controllers, it operates with some predictive models that give an expected behavior of the system concerning control actions—allowing power grids with high penetration of variable renewables like solar PV and wind to use MPC very effectively. A key strength in this respect is that MPC can handle many system constraints, which is its great strength for complex open multi-area systems. By predicting power imbalance actions, it, therefore, improves the effectiveness of Load Frequency Control (LFC) while optimizing battery energy storage system (BESS) availability, thus reducing the need for conventional reserves and enabling the sustainable operation of the grid [

31]. Even though MPC is implemented in real time, it is computationally intensive, particularly for large systems, as the optimization must be solved at each control interval. To address this issue, hybrid MPC approaches incorporating machine learning are currently being studied to reduce the computational burden while maintaining predictive accuracy and robust control performance.

2.2.3. AI Based Control Strategies (Neural Networks, RL and ANFIS)

Advanced control methodologies, including neural networks (NNs), reinforcement learning (RL), and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS), provide effective solutions for addressing nonlinearity and uncertainty in renewable-integrated power systems. These methodologies analyze previous trends and adapt control actions in real-time, surpassing traditional fixed-gain PID controllers. Most AI-based controllers do not begin to operate until something goes wrong, so they are not very useful in rapidly changing grid conditions [

32,

33]. Recent research emphasizes combining AI forecasting with real-time control techniques such as Model Predictive Control (MPC). This combination allows us to adjust before issues arise. Combining forecasting and control makes networks that rely heavily on renewable energy more flexible and resilient [

34].

2.2.4. Hybrid AI-PID Approaches for Enhanced Load Frequency Control

The combination of AI-driven forecasting and adaptive methods with conventional PID controllers is revolutionizing load frequency control (LFC) in today's power systems. As the penetration of renewables continues to increase, hybrid control strategies are being utilized more to enhance the dynamic performance and robustness of LFC. Methods like Support Vector Regression (SVR), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, fuzzy logic, and Model Predictive Control (MPC) have been utilized to augment the deficiencies of PID.

Neural Networks & LSTM Models: Employed to simulate dynamic system behavior and forecast future states [

35,

36].

Fuzzy-PID Controllers: Suitable for real-time disturbances but handicapped by absence of foresight [

37].

Model Predictive Control (MPC): Makes optimal dispatch decisions based on predictions; demonstrated to enhance BESS performance and mitigate frequency deviations [

38,

39].

2.3. Types of Forecasting Methods in Power Systems

Forecasting plays an important role in the planning and real-time operation of power systems. The methods are usually divided into classifications based on time horizons—short-term (minutes to days), medium-term, and long-term—and further categorized as statistical, machine learning (ML) methods, and hybrid techniques [

40].

2.3.1. Short-Term Forecasting Methods (Minutes to Days)

Short-term forecasting is important for real-time grid operations, frequency control, and dispatching batteries, and these methods employ high-resolution data, such as smart meter readings and weather data [

41].

2.3.1.1. Statistical Forecasting Methods

Statistical methods such as ARIMA, exponential smoothing, and Kalman filtering predict near-term trends based on a historical database [

42,

43,

44]. SARIMAX particularly considers seasonal effects and weather inputs for solar forecasting purposes. However, these models struggle with nonlinear patterns typical of solar variability [

45].

2.3.1.2. Machine Learning Based Approaches

Machine Learning methods such as Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks absorb highly complex and nonlinear relationships and are extremely viable in dynamic situations. They combat abrupt changes due to irradiance, temperature, and cloud cover more adequately than other methods [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

2.3.1.3. Hybrid Models

Hybrid models combine the advantages of statistical and ML methods to provide better accuracy and resilience. These models integrate linear pattern recognition with non-linear learning, which suits them for volatile renewable energy systems [

53,

54].

2.3.2. Medium -Term Forecasting (Weeks to Months)

Medium-term forecasts are generally meant for grid planning, maintenance scheduling, energy trading, and strategic allocation of resources. Such forecasts recognize wider patterns of demand and socioeconomic factors and thereby offer guidance for decisions lasting from weeks to several months ahead [

55,

56,

57].

2.3.2.1. Statistical Methods

It uses common methods like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA), and Holt-Winters Exponential Smoothing. These types of models exhibit seasonal trends and a long-time perspective for the behavior of consumption but fail to accommodate the nonlinearity in variability that characterizes renewable sources [

58,

59].

2.3.2.2. Machine Learning-Based Approach

ML algorithms such as ANNs, decision trees, and XGBoost model complex seasonal and non-linear load patterns effectively. ANN is very precise with a value of average correlation coefficients higher than 0.95 when modeling their electricity consumption. Moreover, XGBoost improves prediction, generalizing by adjusting errors with gradient-boosted regularization and proving effective for utility-scale forecasting [

60].

2.3.2.3. Hybrid Models

Hybrid models like SARIMA-ANN and XGBoost-Kalman filters combine conventional linear time-series forecasting with machine learning adaptability. Structured trends are modeled with SARIMA, which can capture nonlinear relationships with ANN. On the other hand, Kalman filters in hybrid settings improve estimations using inputs from real-time observations under uncertain weather and economic conditions to yield better prediction accuracy [

61]. These models provide good ground for medium-term planning in a modern energy system where seasonal variability and external factors affect consumption and generation.

2.3.3. Long-Term Forecasting (Years to Decades)

Long-term forecasting is essential in strategic planning for grid growth, infrastructure upgrades, energy policy formulation, and sustainability objectives. Unlike short-term forecasting, it considers macroeconomic trends, climate legislation, and technological advancements to plan for future energy needs [

62,

63].

2.3.3.1. Statistical Methodologies

Conventional methods of long-term energy forecasting tend to be based on techniques like Bayesian forecasting, cointegration analysis, and Markov chain modeling. These methods utilize past trends and probabilistic associations to forecast how future energy demand is likely to change. By identifying consistent patterns over time, they help inform planning decisions related to infrastructure upgrades, capacity expansion, and strategic policy development [

64].

2.3.3.2. Machine Learning Approaches

Advanced machine learning techniques such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and Transformer models excel at capturing complex temporal connections and changing consumption behaviors. Their strengths lie in digesting sequential data and adapting to changing grid dynamics, making them suitable for long-term prediction [

65].

2.3.3.3. Ensemble and Tree-Based Methods

Random Forests and Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs) are extremely effective at modeling non-linear relationships through the combination of many decision trees. They are beneficial to long-term solar power forecasting due to the ability to cope with high-dimensional sets of features as well as resistance to noise [

66,

67].

2.3.3.4. Support Vector Machines, or SVMs

Short-term solar predictions with small datasets are made possible by SVMs' ability to cope with non-linear regression in lower-dimensional spaces. However, the validity of temporal relationships in long-term predictions is limited by the challenge of modeling them [

68,

69,

70] .

2.3.3.5. Artificial Neural Networks, or ANNs

ANNs helps us understand the complex interactions between things like sunlight levels, temperature, and power output. By using specific weights and layers, these models can predict outcomes accurately over long periods after they are trained sufficiently [

71].

2.3.3.6. Hybrid Models

By combining machine learning and statistical methodologies, hybrid models enhance predictions. For example, they might employ Kalman Filters with Generalized Boosted Models (GBMs), Monte Carlo simulations with deep learning, or SARIMA with Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). These combinations allow the models to leverage the strengths of both approaches to improve their forecasting abilities. These combinations help models handle both straightforward trends and complex patterns, making them more reliable in uncertain conditions [

72].

2.4. Research Gaps in LFC

The integration of renewable forecasting and control techniques for real-time grid frequency management faces essential barriers despite the significant advancements made in these fields:

The application of machine learning models, including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Support Vector Regression (SVR)for short-term load and generation forecasting has been highly successful, yet their implementation in real-time frequency regulation using PID controllers remains restricted. The existing gap leads to a reactive system response instead of an anticipatory one.

There are several disadvantages associated with fuzzy-PID controllers. Although fuzzy logic enhances the adaptability of PID controllers in uncertain situations, these fuzzy-PID controllers are inadequate in terms of their predictive capabilities. They are less effective at managing rapid changes from renewable energy sources such as solar PV because they typically respond only after frequency deviations occur.

MPC and AI-based forecasting are the only options presented in the literature. Comprehensive experiments showing a full control system using SVR predictions to run an MPC-designed battery dispatch system, which then feeds data into a DE-tuned PID controller for frequency stability, are lacking in the literature. The forecasting system's efficiency is reduced when it is not coordinated with the energy storage and control system

2.5. Addressing the Gaps Through the Proposed Framework

This research introduces a novel hybrid control framework that bridges the gap between intelligent forecasting and real-time frequency control in a two-area solar-thermal power system:

SVR is used to accurately predict near-future solar generation and load demand using lagged time-series inputs. These projections enable proactive analysis of imbalances prior to affecting the system frequency.

Real and future mismatches are utilized to make decisions about charging or discharging a battery using a lightweight MPC-inspired approach. This feature supports the stability of net demand in real time by acting prior to frequency aberrations.

A PID controller, tuned using Differential Evolution, receives Area Control Error (ACE) feedback from the solar-integrated region. The DE optimization minimizes time-domain performance indices such as overshoot, settling time, and steady-state error, providing dynamic and adaptive correction.

Collectively, the components constitute an intelligent closed-loop control structure that actively compensates for frequency fluctuations, stabilizes tie-line power transfer, and optimally utilizes battery energy storage. The method is tested against actual solar power generation data for the Mirzapur Solar Power Plant, and it presents an applicable solution towards improving grid resiliency during high renewable integration.

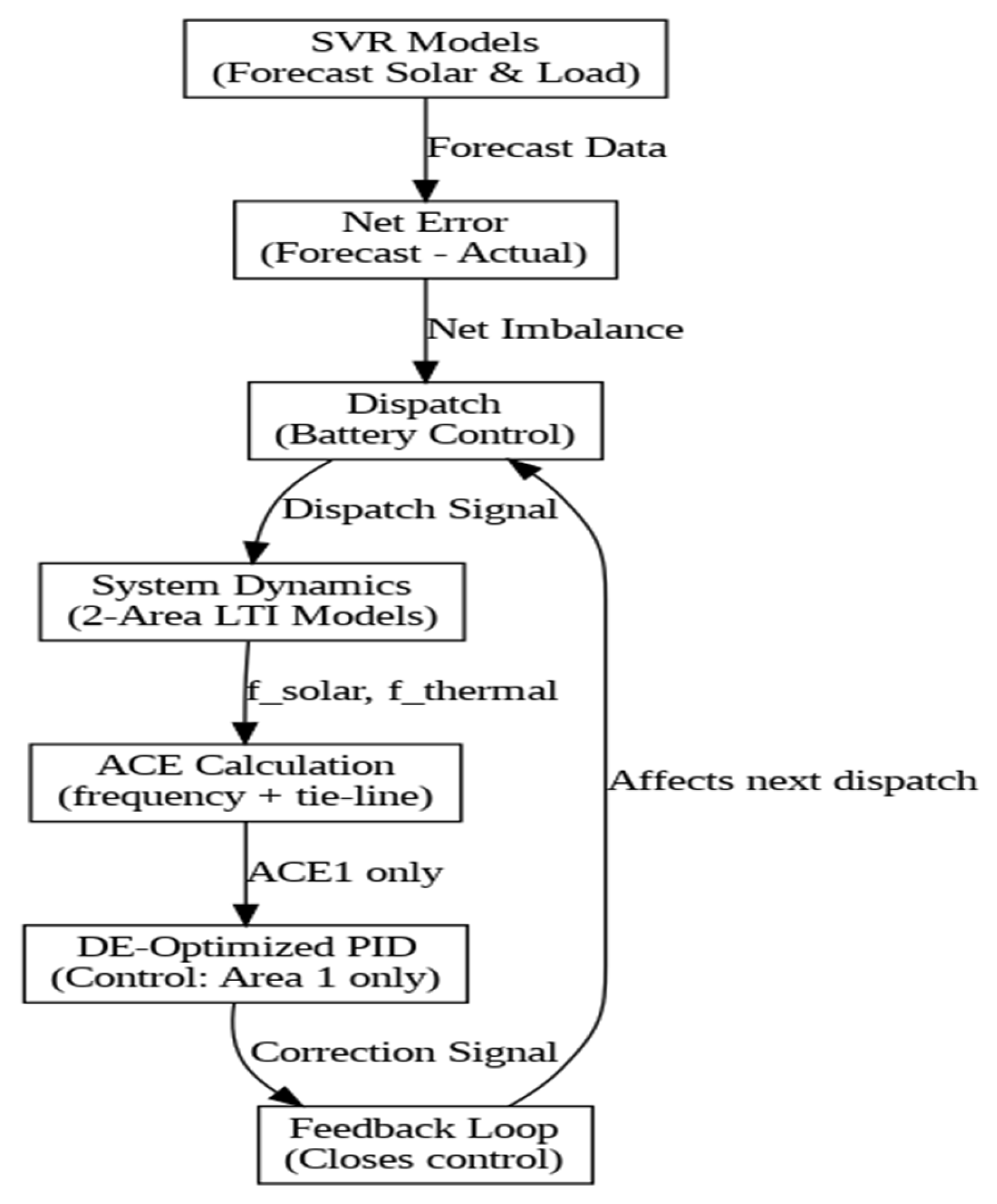

3. Overview of Proposed Hybrid Controller

This research proposes a hybrid control architecture with a view to implementing frequency and power stability in two-area systems integrating solar and thermal energy resources. The controller design integrates short-term forecasting, predictive dispatch, and real-time feedback regulation and is specifically aimed at dealing with operational issues arising from solar photovoltaic (PV) generation intermittency in an interconnected system.

It was designed to be modular and to include the fundamental elements below:

Support Vector Regression (SVR) used for the short-term forecasting of solar energy generation and electrical load demand. Using lagged historical data for predicting future values makes it possible to make anticipatory assessments of generation-demand imbalance.

With the Model Predictive Control (MPC) logic, Predictive Dispatch calculates in real-time the optimal charge-discharge actions of the battery. It proactively responds to forecasted mismatches between solar generation and demand.

The system dynamics simulation includes solar and thermal generation areas as interconnected second-order Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) systems. The simulation can capture the effect of dispatch signals on frequency deviations as well as tie-line power exchange between the two areas.

ACE is the area control error calculated in each area to ascertain how much the regulation error is due to frequency deviation and tie-line power flow. ACE1 indicates the area control error in solar area (Area 1), while ACE2 refers to the thermal area (Area 2).

Differential Evolution (DE)-Optimized PID controller takes the ACE1 output for the computation of corrective control signals. The DE algorithm optimizes the PID gains to ensure that they minimize performance indices, such as overshoot, steady-state error, settling-time, and rise-time. The feedback control loop actively regulates only the solar area (Area 1). On the other hand, Area 2 (thermal) is characterized by dynamic generation characteristics but remains passive in terms of control. It responds naturally to dispatch-induced disturbances and tie-line flows but does not receive direct corrective action from the controller.

Figure 1 depicts the complete flow of control actions in the proposed SVR + MPC-Based Predictive Dispatch + DE-PID hybrid controller frameworkThis section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Methodology

This study introduces a hybrid AI-control optimization framework that integrates Support Vector Regression (SVR) for load forecasting, Model Predictive Control (MPC) for optimal battery dispatch, and a Differential Evolution (DE)-optimized PID controller for frequency and tie-line power regulation in a two-area power system. The approach is organized into the subsequent steps:

4.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

This research utilizes actual solar generation data from the Mirzapur Solar Power Plant, an important renewable energy project in India. The dataset comprises time-stamped records of actual solar power output in megawatts (MW) under standard operational conditions. There was no artificial scaling done so that the inherent randomness and variability of the solar generation profile could be maintained.

The solar dataset is with two main objectives:

To build a short-term solar energy generation forecasting model based on Support Vector Regression (SVR).

To mimic real-time system dynamics where battery allocation and frequency regulation would be assessed.

One synthetic load profile was created to imitate the real demand conditions as no actual load data of the site were available. The synthetic load profile consists of both deterministic and stochastic elements:

And so, the synthetic load signal was then utilized as a secondary time series for short-term forecasting through a different SVR model.

4.2. Solar PV Generation and Load Forecasting Using Support Vector Regression (SVR)

In anticipation for dispatch and frequency regulation, Support Vector Regression (SVR) was used to prepare short-term forecasting for solar generation and electrical load demand. SVR is very good at non-linear modeling in time series data with moderate volume and variability-these are mostly characteristics of power systems with renewable sources.

4.2.1. SVR Input Design and Feature Engineering

Two SVR models were developed independently

In both cases, the input was a sequence of the past 12 consecutive values, and the output was the predicted value at the next time step. This sliding window approach captures temporal trends effectively:

where n is the lag horizon (e.g., 12 steps), and each lag represents past generation at previous time intervals.

This formulation lets the model capture short-term trends and fluctuations in generation and demand in fine details, being very important for efficient predictive dispatch.

4.2.1. Model Training

Prior to training, all input and target values were MinMax scaled to range [0, 1]. This ensures consistency in learning across features and avoids large-magnitude inputs from dominating the learning process.

The training dataset was formed through a sliding window technique where for every point in the time series, the previous 12 values were taken as input and the next value as the target for prediction. This rolling format allows better detection by the model of trends on the move and adaption to near-future variability of the data.

4.2.2. SVR Configuration Parameters

For SVR model, the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel was preferred; this model tried to catch the nonlinear patterns in time series data, which are quite common instances in solar power generation. There were a few parameters that were further fine-tuned to help the model learn well to produce stable predictions, such as:

C (regularization parameter) = 100: this determines how the model keeps trying to avoid errors; higher values produce more focus on accuracy.

γ (gamma) = 0.01: this Kernel coefficient defines how far each data point influences the model's decisions.

epsilon = 0.01: This defines a small tolerance margin for zero penalization of prediction error, smoothing out fluctuations.

4.2.3. Integration with Control System

Once trained, the SVR models were integrated into the hybrid control framework and used to provide one-step-ahead forecast of solar generation and load demand at each simulation step. These forecasts were subsequently used as input for the predictive dispatch logic to charge or discharge the battery in expectation of an impending mismatch, thus stabilizing frequency and enhancing system responsiveness.

4.3. Battery Dispatch Optimization Using an MPC (Model Predictive Control) -Inspired Strategy

To maintain real-time power balance in the two-area hybrid power system, a lightweight dispatch logic inspired by Model Predictive Control (MPC) is employed. Rather than solving a full optimization problem at every step (as in classical MPC), the controller uses a computationally efficient proportional control rule that reacts to the mismatch between forecasted and actual net demand.

At every step of the simulation, forecasts of solar generation and electrical load are done with Support Vector Regression (SVR).

4.3.1. Net Power Imbalance Calculation by Controller as:

Imbalance = () − (Actual Load − Actual Solar)

This imbalance is used to determine the battery dispatch: The coefficient 0.5 serves as a proportional gain to moderate the reactive response of dispatch.

It is based on the realistic assumption that the battery only makes up for a portion of the net imbalance and renders the response stable and realistic for physical systems.

Even if the strategy does not directly solve the MPC cost function, it retains the predictive nature of MPC:

Future values (forecasted using SVR) have influence on current decision-making

At each timestep, dispatch is updated based on prediction errors

Operational constraints of the battery are enforced through embedded logic.

4.3.2. Battery Constraints and SOC Management

To ensure reliable and secure battery efficiency dispatch options are constrained by the physical limitations of the battery's state of charge (SOC):

Initial condition: = 0.5 ×

The battery dispatch is bounded at each time step to reflect charging and discharging limits.

At each time step, the state of charge of the battery is updated with a dispatch value and clipped to the specified limits. This ensures safe operation and enables the battery to contribute toward frequency regulation and generation–demand mismatches.

4.4. System Dynamics Modeling and Frequency Response

To investigate the impact of battery dispatch and generation fluctuations on power system behavior, the two-area hybrid power system is modeled using second-order Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) dynamic equations. This abstraction allows the simulation of frequency responses and tie-line power flow between interconnected areas representing the solar (Area1) and thermal (Area2) power regions.

4.4.1. Two-Area Model Representation

Each area responds dynamically to dispatch signals and generation variations:

Area 1 (Solar Region) is more sensitive to imbalance and includes the fluctuations of solar generation and battery interaction.

Area 2 (Thermal Region) is modeled as a slow system exhibiting inertia-dominated behavior of conventional thermal power plants. Though thermal generation does not maintain a constant rate, its variation is slow and limited, resembling a system that can hardly respond to external disturbances. In this model, Area 2 is assumed to provide a base load of 40 MW, which serves as a reference point for evaluating frequency deviations caused by thermal output changes.

The response of the system is governed by simplified frequency deviation models:

The solar frequency deviation reflects a negative response to dispatch magnitude.

The thermal frequency deviation shows a small increase with dispatch but is also compensated by the gradual offset adjustment due to thermal generation's deviation from its nominal baseline of 40 MW. This term represents the gradual adjustment and inertia-like response of Area 2.

4.4.2. Tie-Line Power Flow Modeling

Thus, to simulate power interchange between areas, tie-line power flow is defined as frequency difference between two areas, such as in:

This component in the power system plays a significant role in the formulation of Area Control Error (ACE), representing inter-area power differences.

4.4.3. Area Control Error (ACE) Calculation

Area Control Error (ACE) is calculated on the basis of frequency deviation and the tie line power flow:

=

=

Where are bias factors which represent frequency sensitivity and participation in regulating tie-line power flows respectively.

These ACE values show the deviation of each area from the scheduled operation. Here only for solar area is used for active feedback control in the proposed model, reflecting the need for more attention given to variable renewable sources.

5. Differential Evolution (DE)-Optimized PID Control as Feedback Loop

A PID controller is applied and tuned using the DE optimization algorithm for correcting the frequency deviations actively in the solar-integrated area (Area 1). The closed-loop control can enhance the system stability by adaptively responding to real-time disturbances especially those brought about by renewable generation uncertainty.

5.1. PID Controller Input: ACE1

The input to the PID controller is the Area Control Error for Area 1, or ACE1. Thus, it incorporates both the frequency deviation locally and the interarea power exchange:

This is a real-time control objective that maintains Area 1 frequency stability, including the effect on the entire grid.

5.2. PID Control Law

The PID controller uses the

as the control error input and produces a corrective action based on:

where:

and are proportional, integral, and derivative gains respectively and is the control signal applied to the system.

This signal influences the system by indirectly correcting future battery dispatch decisions through the feedback loop.

5.3. Tuning via Differential Evolution (DE)

The PID controller gains and were optimized using a Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm, which is a population-based metaheuristic that is very robust for nonlinear control problems. The purpose of tuning is for improvement in frequency stability and dynamic response in the solar-integrated area (Area 1) of the two-area hybrid power system.

The Differential Evolution (DE) method is utilized to tune the PID controller in terms of minimizing frequency deviations occurring within the system. The cost function used for tuning the PID controller focuses on minimizing the total Area Control Error in the solar area only over the entire simulation time horizon: specifically, it is given as:

where:

This formulation ensures that the optimization process directly takes control in the solar area. Although classical performance metrics rise time, overshoot, settling time, and steady-state error are not defined within the cost function, they are implicitly improved as a result of reducing cumulative ACE1 values.

5.4. Closed-Loop Feedback Operation

The PID correction is done at every simulation time step to establish a feedback loop in real-time:

Battery dispatch affects both solar and thermal frequencies.

System dynamics generate frequency deviation and tie-line flow.

ACE1 is calculated.

PID controller processes ACE1 and issues an output for corrective action.

The output of the controller indirectly guides the dispatch in the subsequent cycle.

In this framework, only Area 1 (solar) is actively regulated through feedback control. Area 2 (thermal), on the other hand, is not directly controlled but instead responds naturally to system changes through its interaction with the tie-line. This reflects a practical design choice, acknowledging that conventional thermal plants tend to operate more steadily and respond more slowly to disturbances compared to variable renewable sources.

5. Simulation Setup

All simulations in the study were carried out in Python 3.9 using libraries such as scikit-learn for SVR-based forecasting, NumPy and pandas for handling time-series data, and matplotlib for visualizing performance. The hybrid control system was scripted as modular Python code and run on Google Colab, covering everything from forecasting to battery dispatch, dynamic model processing, and PID tuning using Differential Evolution (DE), for ease of experimentation and reproducibility.

The system being studied is a hybrid power system that operates in two areas.

Area 1: A solar photovoltaic (PV) plant is prescribed along with a battery energy storage system (BESS), with consideration for the variable, fast, and responsive renewable source.

Area 2: A power plant that generates thermal energy, designed to operate more steadily with slower movements and controlled participation.

5.1. Forecasting Configuration

To facilitate the implementation of short-term forecasting within the control loop, two separate Support Vector Regression (SVR) models were developed:

The solar forecasting model was trained using actual solar generation data from the Mirzapur Solar Power Plant.

The load forecasting model used synthetically generated demand data designed to resemble realistic day-to-day consumption patterns, which includes both regular (diurnal) variations and random fluctuations.

The models were simplified and then abstracted to a lag window of 12-time steps, where each forecast was based on the previous 12 values in the time series. Every input feature and output target were scaled in the direction of the interval [0, 1] through MinMax normalization ahead of training. This normalization was that this balances and increases the aggressiveness in the learning behavior of the model.

5.2. Battery Dispatch and SOC Settings

These bounds prevent overcharging and deep discharging, allowing the battery energy storage system to reliably absorb or supply power and smooth out short-term mismatches between generation and demand.

A simple proportional control scheme is used for determining the battery dispatch at each simulation step, which considers the difference between forecasted net demand and actual demand. The dispatch equation reads as follows:

Here, are denote the SVR-forecasted load and generation values, while L and G are the actual observed values. The proportional control gain of 0.5 dampens the battery's response so that only part of the detected imbalance is compensated for, thus preserving system stability.

The state of charge of the battery is then updated continuously in an iterative fashion after each dispatch within defined operational limits to ensure safety and life:

They ensure the restriction of overcharge and deep discharge, thereby allowing the battery energy storage system to reliably absorb or inject power and smoothen instantaneous short-term mismatches between generation and demand.

5.3. System Dynamics and Frequency Modeling

To simulate how each area reacts to scheduled actions and generation-demand imbalances, both regions are modeled as simplified second-order Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) systems, closely approximating frequency behavior.

Area 1 which consists of solar PV generation and battery storage, is more sensitive area to fluctuations; hence frequency deviation with regards to solar PV generation and battery storage is modeled as:

This equation indicates that with increasing dispatch due to an imbalance, the system frequency drops, representing the rapid dynamics and variability of solar-based systems.

Area 2 signifies a conventional thermal generation mode. Although not constant, the elegant model tries to reproduce output dynamics that are much slower and smoother with inertia-controlled thermal plants. The frequency deviation in Area 2 is given as:

Here, the small correction term (Actual Thermal Output-40) simulates the thermal generator’s inter fluctuation around its nominal capacity.

The thermal generation is modeled as:

This captures both gradual sinusoidal variation and random noise, depicting the behavior of a real thermal system that operates smoothly but not rigidly.

5.4. Area Control Error and Feedback

The interconnection between the two areas is represented by the tie-line power flow, which quantifies the imbalance in frequency between the solar and thermal regions. It is computed as:

Using this tie-line flow, the Area Control Error (ACE) is calculated separately for each area. These ACE values quantify how far each area deviates from its nominal frequency and scheduled inter-area power exchange:

In the proposed control framework, ACE1 is the only input to the DE-optimized PID controller corresponding to the solar area. While ACE2 is calculated for the purpose of evaluating performance, this variable does not enter the control loop. Based on ACE1, the corrective signal is consequently routed only into the dispatch logic of Area 1. This signifies a control strategy that actively manipulates the solar-integrated region's variability while allowing the thermal area to adjust passively through tie-line dynamics.

5.5. PID Controller and DE Optimization

A PID controller is used to increase frequency stability in the solar-integrated region. This controller accepts the ACE1 signal indicating frequency deviation and the tie-line imbalance in Area 1 and provides for an instantaneous corrective control action.

Rather than using fixed or manually tuned gains, the PID parameters are optimized using the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm. DE is one of the population-based metaheuristics that are particularly successful in nonlinear multi-objective optimization problems.

The DE algorithm is used to find the optimal combinations of PID gains Kp, Ki, and Kd by minimizing a custom cost function defined from key performance indices obtained from the ACE1 response, such as overshoot, steady-state error, settling time, and rise time.

The tuned PID controller works in closed feedback, processing the ACE1 signal for any change at every time step to update the system response accordingly, thereby providing an adaptive frequency regulation scheme to the solar area. This feedback structure allows the system to modulate its response to disturbances, thereby aiding grid stability during renewable fluctuation.

6. Results and Discussions

To assess the impact of the DE-optimized PID controller, we first simulated the system under SVR-based forecasting and MPC-inspired battery dispatch alone. Subsequently, the DE-tuned PID controller was introduced as a feedback layer using ACE1 as input.

6.1. Forecasting Performance

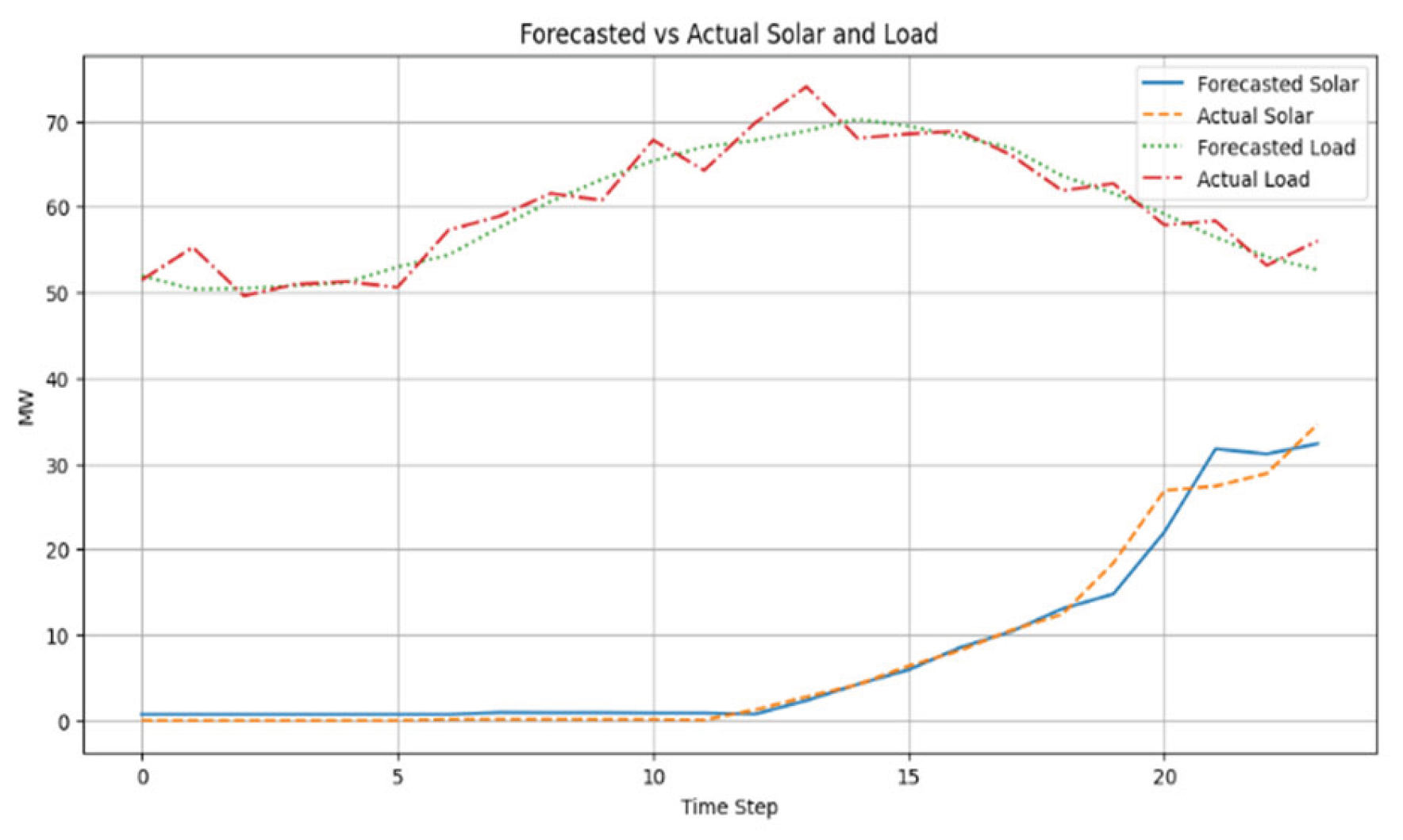

The performance of the SVR-based forecasting models was assessed by plotting actual and predicted values for both solar generation and load demand against the simulation horizon of 24 steps.

Forecasting solar generation has been very close to actual measurement data from the Mirzapur Solar Power Plant, as shown in

Figure 2. Despite the presence of fluctuations due to inherent solar variability, the SVR model successfully captured the general trend and short-term dynamics of solar output. Minor deviations were observed during periods of rapid change, which is typical for renewable time-series forecasting.

Very similar to that, the synthetic load forecast (also shown in the

Figure 2) strongly aligns with the actual synthetic demand profile. The SVR model was able to track both the diurnal pattern and the random variations which are superimposed on the load signal. It can, therefore, be confirmed that the SVR model learns and generalizes short-term demand behavior in noisy conditions.

This accurate forecasting is the basis of the control framework. Through one-step-ahead accurate predictions, the system can actively manage battery dispatch rather than reactively, thereby averting potential mismatches before they occur.

6.2. Battery Dispatch and SOC Behavior

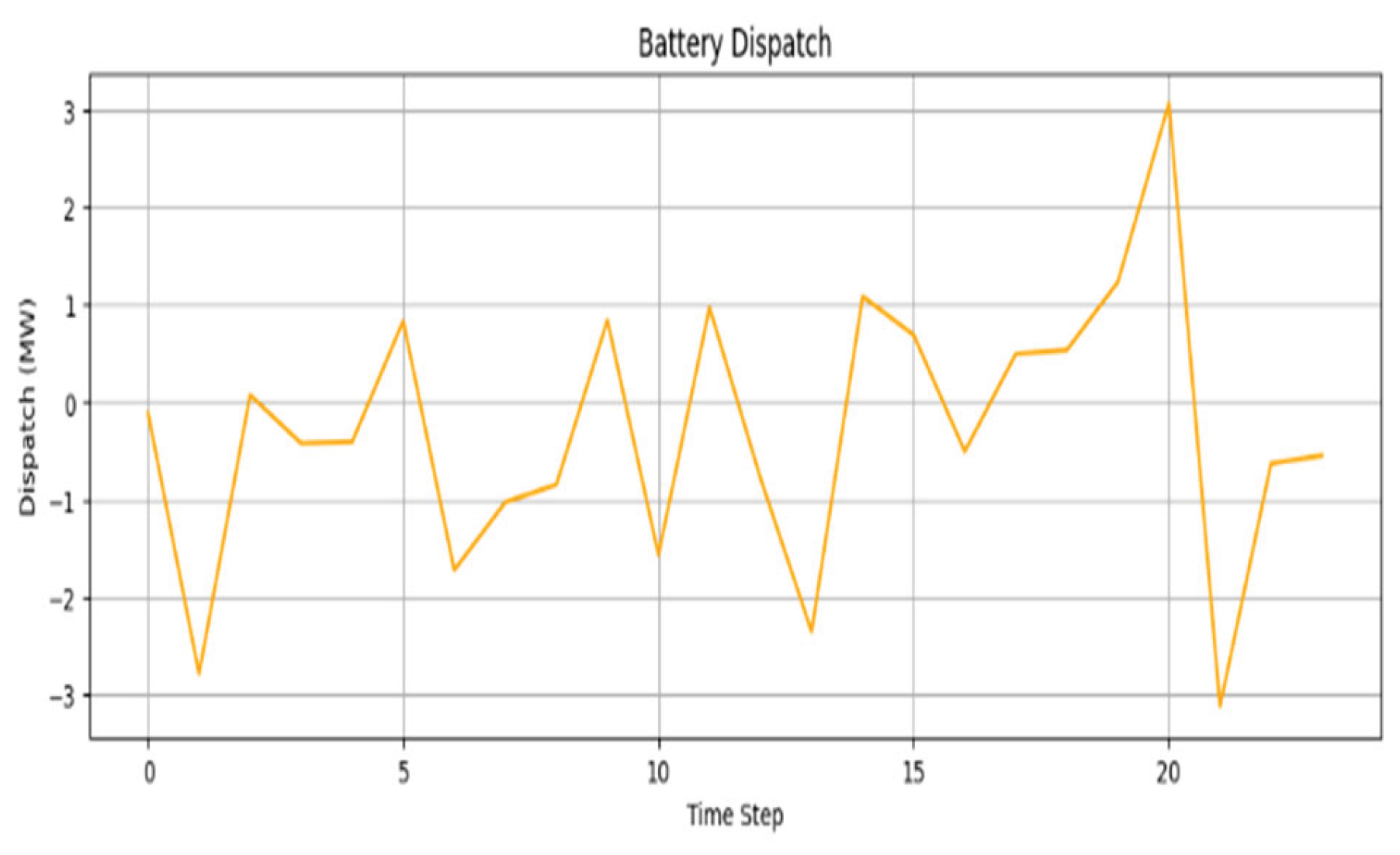

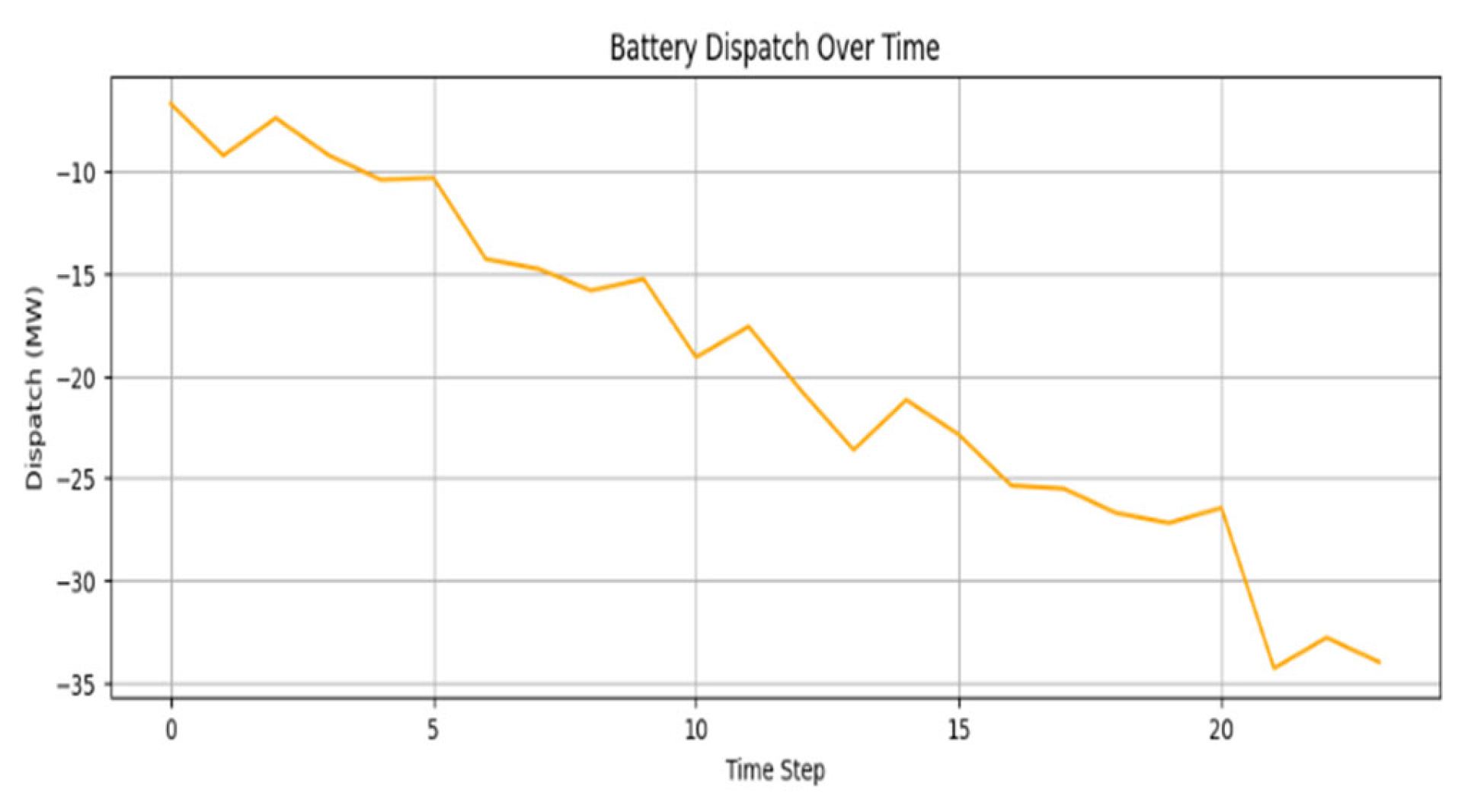

Battery energy storage system effectively neutralizes the mismatch between the predicted and unpredicted net demand. The dispatch signal results from a proportional control rule, which indicates how much must be charged/discharged the battery concerning the instantaneous system imbalance.

As depicted in

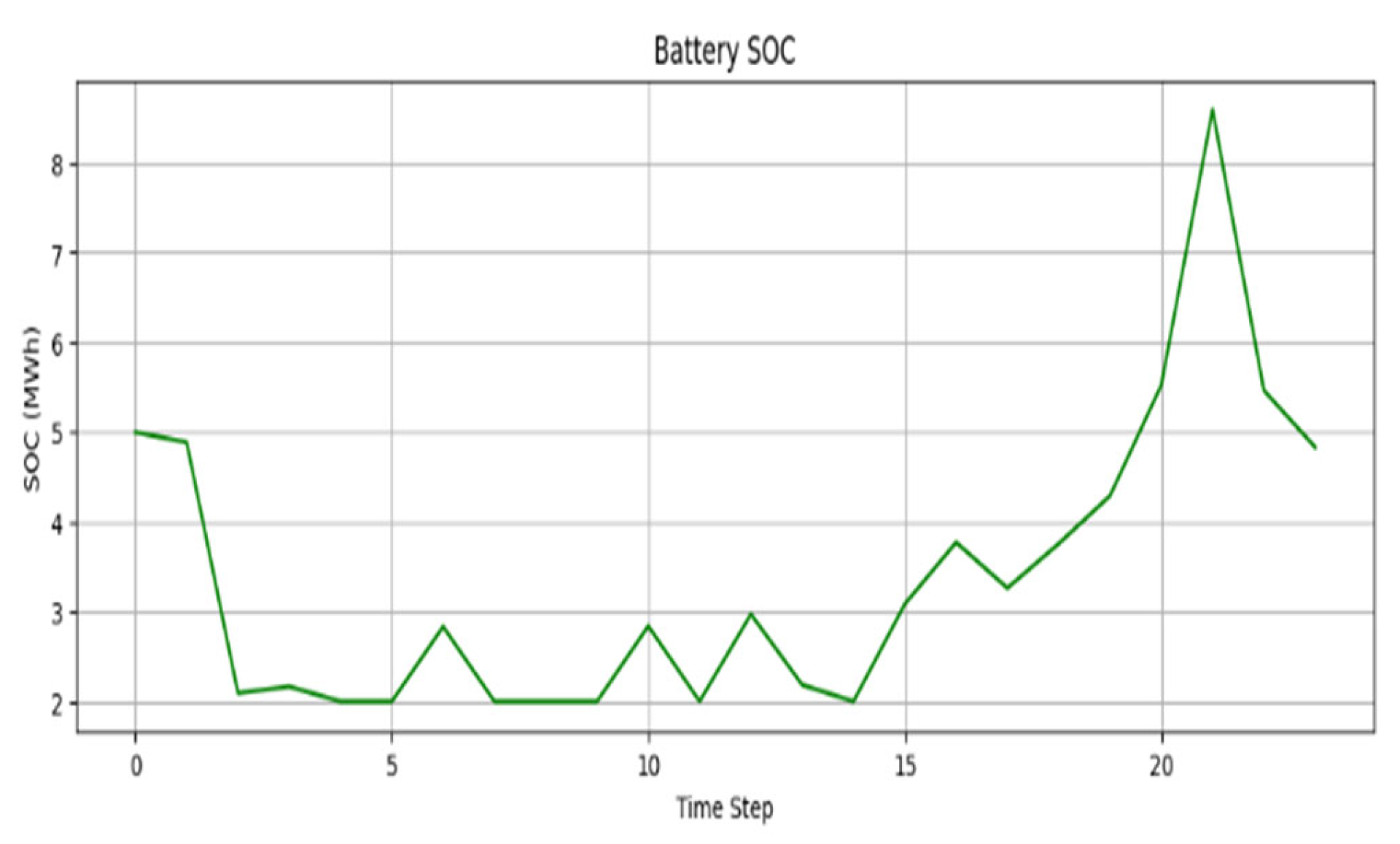

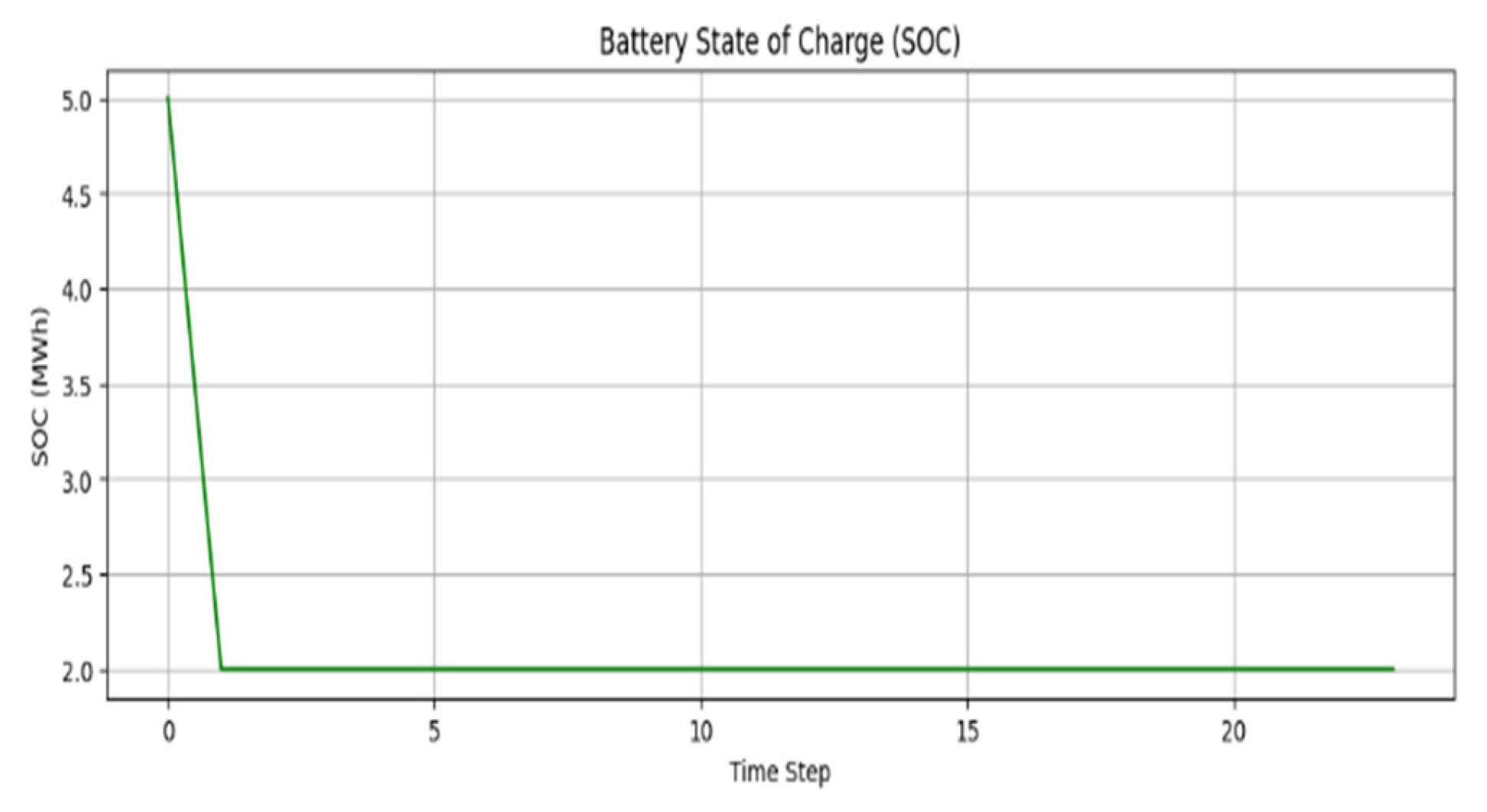

Figure 3, the battery dispatch varies dynamically over the entire 24-step simulation horizon. A positive dispatch value indicates discharging (battery supplying power to the grid), while charging refers to negative dispatch values (i.e., absorbing excess power). The battery responds in a more aggressive manner when forecasted and actual values differ significantly so that it can assist in buffering frequency deviations to the solar area. Along with this, the State of Charge (SOC) profile (as shown in

Figure 4) validates the safe operational limits of the battery during the entire simulation. The SOC gradually evolves over time being influenced by dispatch actions, remaining.

bounded by the constraints between 20 percent and 90 percent of total capacity.

The results confirm that the MPC-inspired dispatch logic coupled with SVR-based forecasting allows a battery to act as a stabilizer correcting short-term imbalances while respecting the physical limit.

6.3. System Behavior Prior to Feedback: Frequency Deviations and Tie-Line Response

The frequency dynamics in both the solar-integrated (Area 1) and thermal (Area 2) regions were studied to characterize the system's natural response to generation–demand mismatches and battery dispatch prior to the application of closed-loop feedback control.

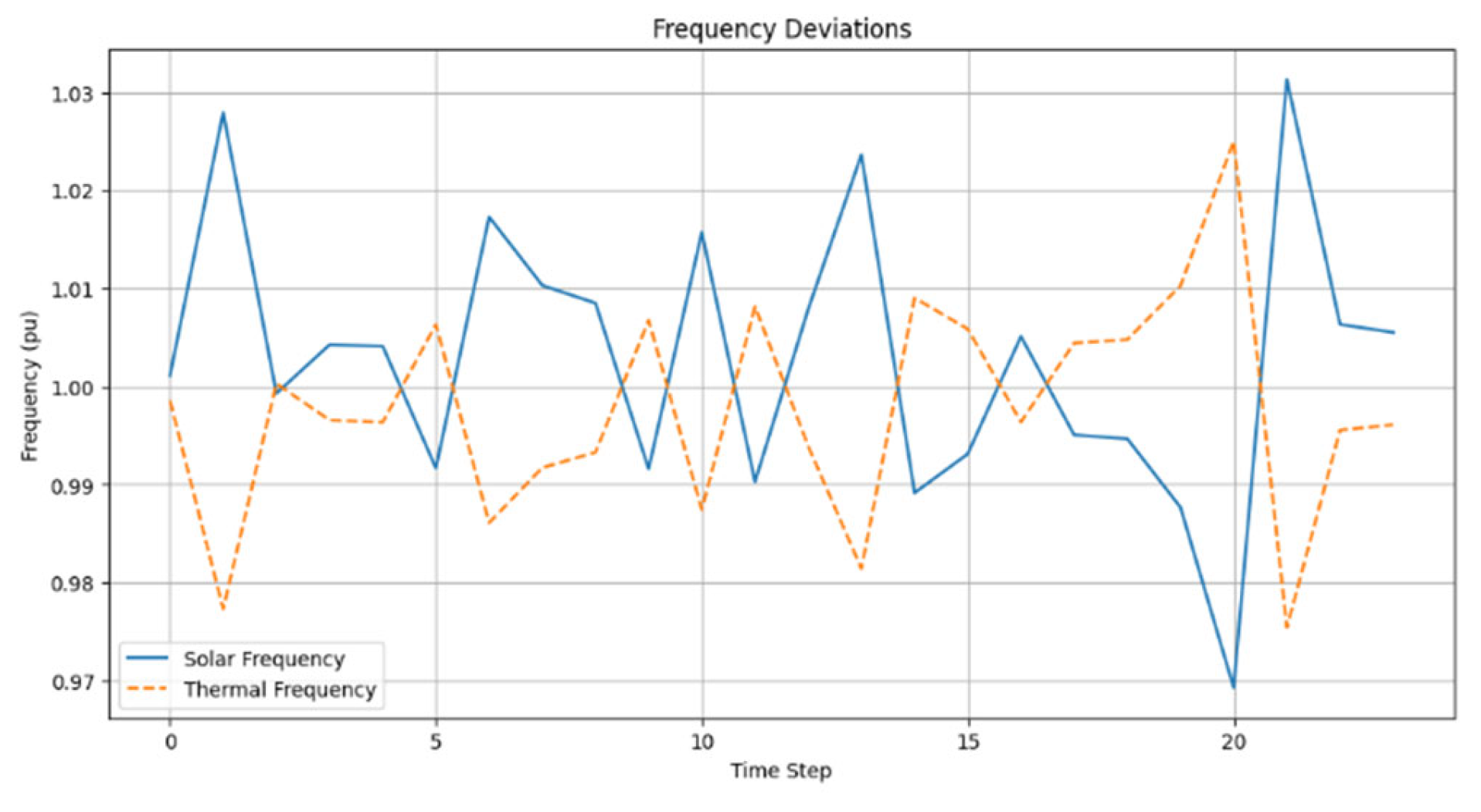

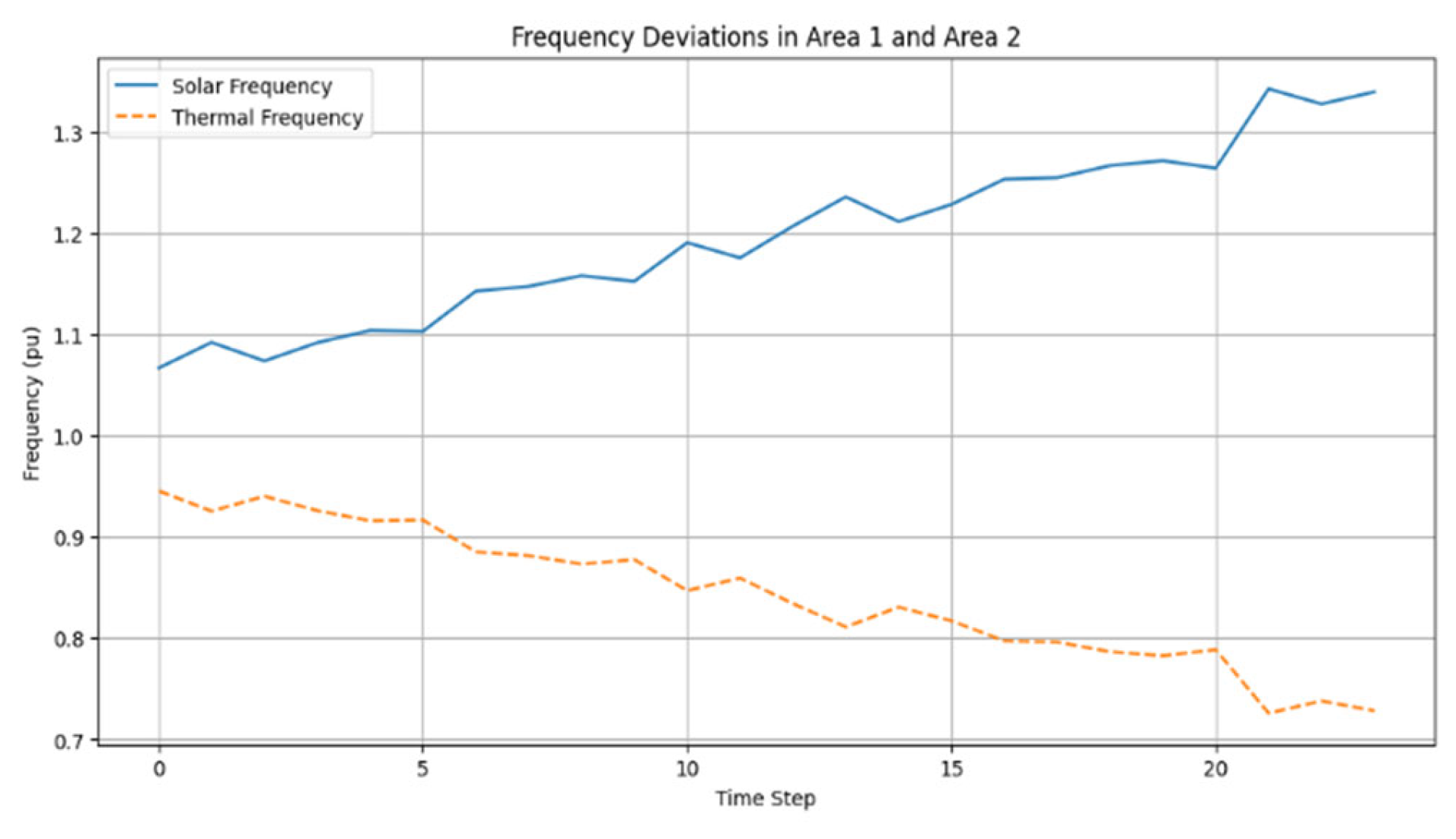

As illustrated in

Figure 5, frequency deviations in Area 1 (solar region) exhibit noticeable variability, consistent with fluctuating solar output and direct battery interaction. The dispatch signal responds to forecast errors; however, in the absence of dynamic feedback, larger frequency excursions tend to persist. These deviations, together with tie-line power imbalances, form the basis for calculating ACE1, which will later serve as the input to the feedback controller.

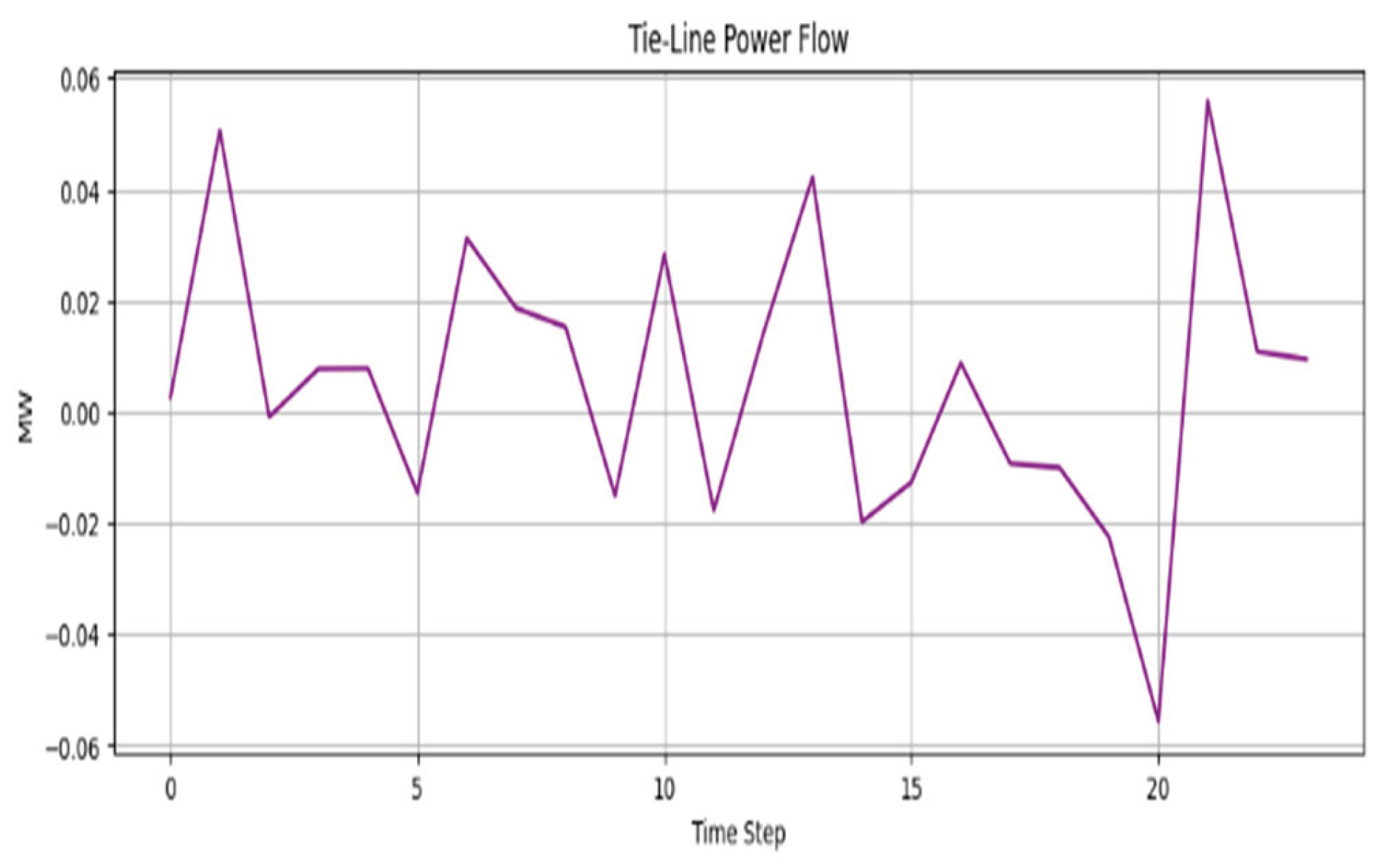

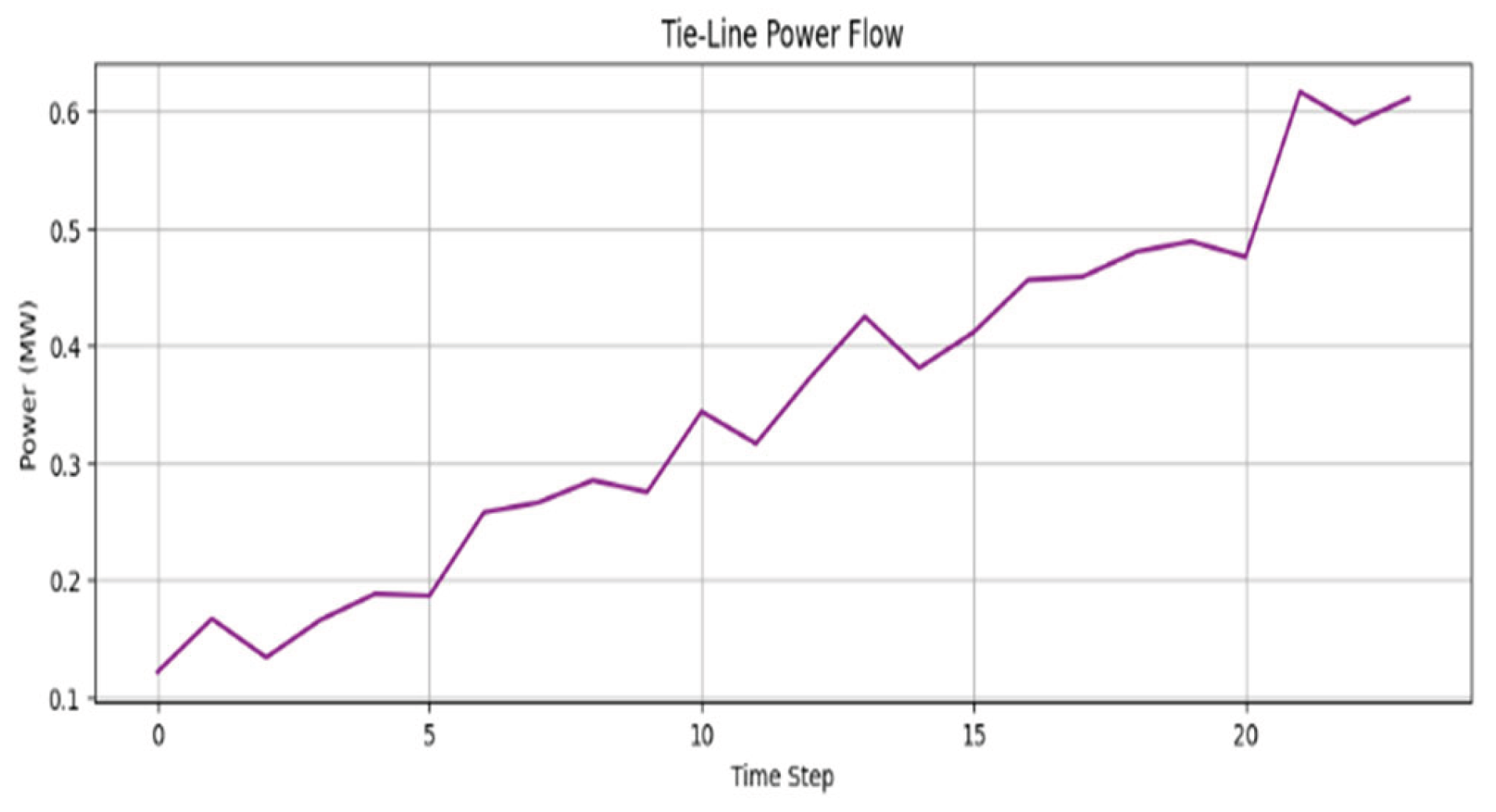

On the other hand, Area 2 (thermal region) exhibits more stable and smooth frequency behavior. This is due to its passive nature and higher inertia since it does not see direct dispatch signals. Rather, Area 2 reacts indirectly through inter-area coupling. The power flow through tie-lines (

Figure 6) indicates frequency-driven transient oscillations between the two areas. These oscillations verify active inter-area balancing, with disturbances in Area 1 being partly absorbed by the interconnected structure.

6.4. Frequency Response Improvement Through DE-PID Feedback Control

To evaluate the effect of the proposed DE-optimized PID feedback controller, we analyzed the Area Control Error (ACE) signals and frequency performance indices as shown in (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). In

Figure 9, the use of the DE-PID controller results in the quick elimination of ACE1 oscillations in the solar-integrated area. The feedback loop, driven by ACE1, enables the controller to adapt dynamically at each time step, reducing high-frequency fluctuations and contributing to quicker stabilization.

Although the thermal region (Area 2) is not actively controlled,

Figure 9 shows that ACE2 remains well within bounds. This passive control is due to the stabilizing effect of the tie-line, which indicates the inter-area balance obtained through coordinated control in Area 1.

Figure 10 shows that tie-line fluctuations also dampened.

A comparative overview of the performance indices—namely rise time, overshoot, steady-state error, and settling time—is given in

Table 1. The indices verify that the optimized control strategy provides improved damping and smooth frequency response for the actively controlled solar area. Regardless of moderate rises in some indices (e.g., Area 1 overshoot), system stability is overall increased with improved ACE regulation and co-ordination of tie-line.

These results validate the function of AI-integrated frequency control, where battery dispatch, evolutionary PID tuning, and predictive forecasting all work together to preserve grid stability in the face of fluctuating solar conditions.

7. Limitations and Future Scope

While the suggested SVR + MPC + DE-Optimized-PID framework has truly improved frequency regulation and operational stability of the hybrid solar-thermal power system, it offers multiple limitations that can be explored in future research and development.

One major limitation of this study is that the authors relied on synthetic grid demand that was generated by means of a fixed diurnal sinusoidal pattern and Gaussian noise. Although, to some extent, this approach is able to mimic general trends in daily consumption, it does not consider behavioral, industrial, or socioeconomic influences inherent in real-world demand. The system, thus, was subjected to examples of idealized load variations in testing the forecasting and dispatching responses. Future works should, therefore, extend their investigations by using actual demand data coming from power utilities. This will help understand more accurately the forecasting ability and control performance under realistic operating conditions.

The battery model utilizes fixed parameters regarding capacity, charge/discharge limits, and efficiency for this framework. While the parameters would be dynamic and influenced by factors such as aging, temperature, and state-of-charge variation. A better dispatching mechanism could possibly integrate battery degradation models along with dynamic efficiency tracking for increased realism and adaptability of the MPC strategy.

Though Differential Evolution effectively optimizes PID controllers to minimize ACE and enhance stability, it is an offline process. Once tuned, the PID gains remain unchanged for the duration of the simulation, rendering the controller less responsive to the real-time changes in the grid. Extensions in the future could employ adaptive tuning procedures such as artificial intelligence-based self-tuning PID algorithms or reinforcement-learning controllers for a continuous learning and adjusting process regarding the system behavior and disturbances.

This study has demonstrated the framework on a two-area model of solar-thermal energy generation. Real-world power systems, however, often consist of a multitude of interconnected multi-area generation sources while matching diverse meteorological patterns. Future work may determine the capability and applicability of scaling this framework to larger multi-area grids, especially those with significant renewable penetration associated with the geographical distribution of variability.

Given that the present model works on deterministic principles and does not explicitly mention uncertainties of solar generation or load forecasting, future work is expected to address probabilistic forecasting methods, stochastic MPC formulations, or robust control techniques, thus enhancing the framework's robustness against forecasting errors and abrupt disturbances to the system owing to renewable generation uncertainty.

Intelligent control systems are ultimately meant to be deployed and operated in real time at utility scale. Therefore, future research should also seek to incorporate this framework with real-time energy markets, regulatory policies, and smart grid communication protocols to bridge the academic simulation with a practical grid implementation.

In summary, while the proposed control strategy has shown promising results for intelligent frequency regulation in hybrid renewable systems, further application in broad terms requires improvement in data fidelity, controller adjustability, uncertainty modeling, and real-world scalability. These represent potential future research directions in relation to AI-driven energy management advances for future smart grids.

8. Conclusions

This study proposed an integrated frequency regulation framework for a two-area hybrid solar PV-thermal power system. Using Support Vector Regression (SVR) for short-term forecasting, a lightweight MPC-inspired battery dispatch strategy, and Differential Evolution (DE)-based PID controller tuning, frequency deviation mitigation, and system stability were achieved. Real Mirzapur Solar Power Plant solar production data and synthetic load and heat profiles simulated grid behavior accurately. Area Control Error damping, dynamic smoothness, and state-of-charge regulation improved significantly, but traditional measures improved only somewhat. The framework's versatility and computational feasibility make it ideal for real-time applications, especially in renewable-rich regions. Future research should aim to apply the technique to systems with multiple areas, use actual load data, and adopt adaptive PID tuning methods to enhance control performance in changing and unpredictable grid conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all individuals and institutions who contributed indirectly to this research. This work was conducted independently without any external financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors confirm that they have no known financial or personal conflicts of interest that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The manuscript's final version has been reviewed and approved by all authors, and they concur with its submission. There are no competing interests.

References

- P. S. Kundur and O. P. Malik, Power System Stability and Control, 2nd ed., New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill, pp. 583–627.

- K. Peddakapu, M. R. Mohamed, P. Srinivasarao, Y. Arya, P. K. Leung, and D. J. K. Kishore, “A state-of-the-art review on modern and future developments of AGC/LFC of conventional and renewable energy-based power systems,” *Renewable Energy Focus*, vol. 43, pp. 146–171, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Gulzar, M. Iqbal, S. Shahzad, H. A. Muqeet, M. Shahzad, and M. M. Hussain, “Load Frequency Control (LFC) Strategies in Renewable Energy-Based Hybrid Power Systems: A Review,” *Energies*, vol. 15, no. 10, p. 3488, 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. I. Elgerd, Electric Energy Systems Theory: An Introduction, 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill, 1982, pp. 327–367.

- A. J. Wood, B. F. Wollenberg, and G. B. Sheblé, Power Generation, Operation, and Control, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2014, pp. 469–472.

- IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces, IEEE Std 1547-2018, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC), “Chapter-1 Executive Summary,” Report on the Grid Disturbances on 30th July and 31st July 2012, Aug. 2012, pp. 1–3. [Online]. Available: https://www.cercind.gov.in/2012/orders/Final_Report_Grid_Disturbance.pdf.

- Energy Institute, “ERCOT Blackout 2021,” University of Texas at Austin, [Online]. Available: https://energy.utexas.edu/research/ercot-blackout-2021. [Accessed: Mar. 2, 2025].

- R. Dash, K. J. Reddy, B. Mohapatra, M. Bajaj, and I. Zaitsev, “An approach for load frequency control enhancement in two-area hydro-wind power systems using LSTM + GA-PID controller with augmented Lagrangian methods,” Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–27, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Haes Alhelou, M. E. Hamedani-Golshan, R. Zamani, E. Heydarian-Forushani, and P. Siano, “Challenges and Opportunities of Load Frequency Control in Conventional, Modern and Future Smart Power Systems: A Comprehensive Review,” Energies, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 2497, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Rasolomampionona, M. Połecki, K. Zagrajek, W. Wróblewski, and M. Januszewski, “A Comprehensive Review of Load Frequency Control Technologies,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 12, p. 2915, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Ba Wazir, A. Althobiti, A. A. Alhussainy, S. Alghamdi, M. Vellingiri, T. Palaniswamy, et al., “A Comparative Study of Load Frequency Regulation for Multi-Area Interconnected Grids Using Integral Controller,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 9, p. 3808, 2024. [CrossRef]

- IEEE Smart Grid, “Frequency Stability and Control in Smart Grids,” IEEE Smart Grid Bulletin, Sep. 2019. [Online]. Available: https://smartgrid.ieee.org/bulletins/september-2019/frequency-stability-and-control-in-smart-grids. [Accessed: Mar. 16, 2025].

- J. Huang and D. Yang, “Improved System Frequency Regulation Capability of a Battery Energy Storage System,” Front. Energy Res., vol. 10, pp. 1–10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Saadat, Power System Analysis, 1st ed. 1999, pp. 257–313.

- V. Kumar, S. Sharma, S. Sharma, and A. Dev, “Optimal voltage and frequency control strategy for renewable-dominated deregulated power network,” Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Jabari, D. Izci, S. Ekinci, M. Bajaj, V. Blazek, and L. Prokop, “A novel artificial intelligence based multistage controller for load frequency control in power systems,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–32, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Mahendran and V. Vijayan, “Model-predictive control-based hybrid optimized load frequency control of multi-area power systems,” IET Gener. Transm. Distrib., vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 1521–1537, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Afaneh, O. Mohamed, and W. Abu Elhaija, “Load Frequency Model Predictive Control of a Large-Scale Multi-Source Power System,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 23, p. 9210, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Wu, D. Ma, K. Xiong, and L. Yuan, “Deep Reinforcement Learning for Load Frequency Control in Isolated Microgrids: A Knowledge Aggregation Approach with Emphasis on Power Symmetry and Balance,” Symmetry, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 322, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, X. Sun, K. Liao, Z. He, and L. Cai, “Model predictive control-based load frequency control for power systems with wind-turbine generators,” IET Renew. Power Gener., vol. 13, no. 15, pp. 2871–2879, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Q. Zeng, X. Q. Xie, and M. R. Chen, “An Adaptive Model Predictive Load Frequency Control Method for Multi-Area Interconnected Power Systems with Photovoltaic Generations,” Energies, vol. 10, no. 11, p. 1840, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Safari, M. Daneshvar, and A. Anvari-Moghaddam, “Energy Intelligence: A Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence for Energy Management,” Appl. Sci., vol. 14, no. 23, p. 11112, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., “Artificial intelligence-based methods for renewable power system operation,” Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng., vol. 1, pp. 163–179, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Esmaeili, “Using a Two-Stage Lead-Lag PSS in an Accurate Combined Model of LFC-AVR to Simultaneously Control Frequency and Voltage in an Interconnected Multi-Area Power System,” J. Oper. Autom. Power Eng., vol. XX, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Fan, A. Mohammadzadeh, N. Kausar, D. Pamucar, and N. A. D. Ide, “A New Type-3 Fuzzy PID for Energy Management in Microgrids,” Adv. Math. Phys., vol. 2022, Art. no. 8737448, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Moslehi, M. Kandidayeni, M. Hébert, and S. Kelouwani, “Investigating the impact of a fuel cell system air supply control on the performance of an energy management strategy,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 325, p. 119374, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Singh, S. Arora, and O. A. Shah, “Enhancing Hybrid Power System Performance with GWO-Tuned Fuzzy-PID Controllers: A Comparative Study,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 709–726, 2024. [CrossRef]

- “What can be the benefits of using PI Fuzzy over PID controller for the control of Energy management system of PV-wind system? | ResearchGate,” Accessed: Feb. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/post/What_can_be_the_benefits_of_using_PI_Fuzzy_over_PID_controller_for_the_control_of_Energy_management_system_of_PV-wind_system.

- A. Bouaddi, R. Rabeh, and M. Ferfra, “A fuzzy-PID controller for load frequency control of a two-area power system using a hybrid algorithm,” Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng., vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 3580–3591, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Qi, J. Zheng, and F. Mei, “Model Predictive Control–Based Load-Frequency Regulation of Grid-Forming Inverter–Based Power Systems,” Front. Energy Res., vol. 10, Art. no. 932788, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Ukoba, K. O. Olatunji, E. Adeoye, T. C. Jen, and D. M. Madyira, “Optimizing renewable energy systems through artificial intelligence: Review and future prospects,” Energy Environ., 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Bello, I. U. Wada, O. B. Ige, E. C. Chianumba, and S. A. Adebayo, "AI-driven predictive maintenance and optimization of renewable energy systems for enhanced operational efficiency and longevity," Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 2823–2837, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Khalid, M. A. M. Ramli, M. S. Khan, and T. Hidayat, “Efficient Load Frequency Control of Renewable Integrated Power System: A Twin Delayed DDPG-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 51561–51574, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Yakout, M. Dashtdar, K. M. Aboras, Y. Y. Ghadi, A. Elzawawy, A. Yousef, et al., “Neural Network-Based Adaptive PID Controller Design for Over-Frequency Control in Microgrid Using Honey Badger Algorithm,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 27989–28005, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Marino and F. Neri, “PID Tuning with Neural Networks,” in Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 11431 LNAI, pp. 476–487, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Barakat, “Optimal design of fuzzy-PID controller for automatic generation control of multi-source interconnected power system,” Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 34, pp. 18859–18880, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Luo, Y. Xu, W. Du, S. Wang, and Z. Fan, “Quantum model prediction for frequency regulation of novel power systems which includes a high proportion of energy storage,” Front. Energy Res., vol. 12, Art. no. 1354262, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhao, X. Zhang, and C. Zhong, “Model Predictive Secondary Frequency Control for Islanded Microgrid under Wind and Solar Stochastics,” Electronics, vol. 12, no. 18, p. 3972, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Jing, H. Di, T. Wang, N. Jiang, and Z. Xiang, “Optimization of power system load forecasting and scheduling based on artificial neural networks,” Energy Informatics, vol. 8, pp. 1–20, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Chauhan, S. Gupta, and M. Sandhu, “Short-Term Electric Load Forecasting Using Support Vector Machines,” ECS Transactions, vol. 107, pp. 9731–9737, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Sethi and J. Kleissl, “Comparison of Short-Term Load Forecasting Techniques,” in 2020 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech), 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Dixit and P. Chavan, “Comparative Analysis of Short-Term Load Forecasting Using Kalman Filter and NARX model,” International Journal of Engineering and Technology, vol. 8, pp. 128–134, 2018.

- S. D. Haleema, “Short-Term Load Forecasting using Statistical Methods: A Case Study on Load Data,” International Journal of Engineering Research, vol. 9, pp. 516–520, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. P. Papaioannou, C. Dikaiakos, A. Dramountanis, and P. G. Papaioannou, “Analysis and Modeling for Short- to Medium-Term Load Forecasting Using a Hybrid Manifold Learning Principal Component Model and Comparison with Classical Statistical Models (SARIMAX, Exponential Smoothing) and Artificial Intelligence Models (ANN, SVM),” Energies, vol. 9, p. 635, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Voyant, G. Notton, J.-L. Duchaud, L. A. G. Gutiérrez, J. M. Bright, and D. Yang, “Benchmarks for Solar Radiation Time Series Forecasting,” Renewable Energy, vol. 191, pp. 747–762, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Najibi, D. Apostolopoulou, and E. Alonso, “Gaussian Process Regression for Probabilistic Short-term Solar Output Forecast,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 130, p. 106916, 2020. [CrossRef]

- O. D. Anderson, “Time Series Analysis and Forecasting: Another Look at the Box-Jenkins Approach,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D (The Statistician), vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 285–303, 1977. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Erten and H. Aydilek, “Solar Power Prediction using Regression Models,” Uluslararası Mühendislik Araştırma ve Geliştirme Dergisi, n.d. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zeng, H. Wu, Z. Liu, L. Zhao, Z. Liang, and others, “Enhancing Short-Term Wind Speed Prediction Capability of Numerical Weather Prediction Through Machine Learning Methods,” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, vol. 129, p. e2024JD041822, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Waheed, Q. Xu, M. Aurangzeb, S. Iqbal, S. H. Dar, and Z. M. S. Elbarbary, “Empowering data-driven load forecasting by leveraging long short-term memory recurrent neural networks,” Heliyon, vol. 10, p. e40934, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Yuan, C. Farnham, C. Azuma, and K. Emura, “Predictive artificial neural network models to forecast the seasonal hourly electricity consumption for a University Campus,” Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 42, pp. 82–92, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xiao, J. Xiao, and S. Wang, “A hybrid model for time series forecasting,” Human Systems Management, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 133–143, 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Yu, L. J. Ming, R. Sumei, and Z. Shuping, “A Hybrid Model for Financial Time Series Forecasting-Integration of EWT, ARIMA with the Improved ABC Optimized ELM,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 84501–84518, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. ur R. Khan, I. A. Hayder, M. A. Habib, M. Ahmad, S. M. Mohsin, F. A. Khan, et al., “Enhanced Machine-Learning Techniques for Medium-Term and Short-Term Electric-Load Forecasting in Smart Grids,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 276, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Shirzadi, A. Nizami, M. Khazen, and M. Nik-Bakht, “Medium-Term Regional Electricity Load Forecasting through Machine Learning and Deep Learning,” Designs, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 27, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Nezzar, N. Farah, M. T. Khadir, and L. Chouireb, “Mid-long term load forecasting using multi-model artificial neural networks,” International Journal of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 389–401, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Ferbar Tratar and E. Strmčnik, “The comparison of Holt–Winters method and Multiple regression method: A case study,” Energy, vol. 109, pp. 266–276, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Ruiz-Aguilar, I. J. Turias, and M. J. Jiménez-Come, “Hybrid approaches based on SARIMA and artificial neural networks for inspection time series forecasting,” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, vol. 67, pp. 1–13, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, D. Wan, J. Feng, T. Shen, and B. Sun, “XGB assisted self-learning Kalman filter for UWB localization,” International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences - ISPRS Archives, vol. 46, pp. 227–233, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Bhattacharya and T. K. Basu, “Medium range forecasting of power system load using modified Kalman filter and Walsh transform,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 109–115, 1993. [CrossRef]

- M. Hasan, Z. Mifta, S. J. Papiya, P. Roy, P. Dey, N. A. Salsabil, et al., “A state-of-the-art comparative review of load forecasting methods: Characteristics, perspectives, and applications,” Energy Convers. Manag. X, vol. 26, p. 100922, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, B. Chen, Y. Li, J. Geng, C. Li, W. Zhao, et al., “Research on medium- and long-term electricity demand forecasting under climate change,” Energy Reports, vol. 8, pp. 1585–1600, 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Long Term Load Forecasting Fundamentals and Best Practices,” EUCI, [Online]. Available: https://www.euci.com/event_post/long-term-load-forecasting/. [Accessed: Apr. 20, 2025].

- “One year long-term electric load forecasting based on multiple regression models and Kalman filtering algorithm,” ResearchGate, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286973538_One_year_long-term_electric_load_forecasting_based_on_multiple_regression_models_and_Kalman_filtering_algorithm. [Accessed: Apr. 20, 2025].

- C. G. Villegas-Mier, J. Rodriguez-Resendiz, J. M. Álvarez-Alvarado, H. Jiménez-Hernández, and Á. Odry, “Optimized Random Forest for Solar Radiation Prediction Using Sunshine Hours,” Micromachines, vol. 13, no. 9, p. 1406, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Soleymani and S. Mohammadzadeh, “Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Solar Irradiance Forecasting in Smart Grids,” arXiv preprint, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/.

- “Solar Power Forecasting Using Support Vector Regression,” ResearchGate. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315696401_Solar_Power_Forecasting_Using_Support_Vector_Regression. [Accessed: Feb. 26, 2025].

- A. Fentis, L. Bahatti, M. Mestari, and B. Chouri, “Short-term solar power forecasting using Support Vector Regression and feed-forward NN,” in Proc. 2017 IEEE 15th Int. New Circuits Syst. Conf. (NEWCAS), 2017, pp. 405–408. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, J. Liu, and J. Wang, “High-Resolution Load Forecasting on Multiple Time Scales Using Long Short-Term Memory and Support Vector Machine,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 4, p. 1806, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Suanpang and P. Jamjuntr, “Machine Learning Models for Solar Power Generation Forecasting in Microgrid Application Implications for Smart Cities,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 14, p. 6087, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S.T. Asiedu, F. K. A. Nyarko, S. Boahen, F.B. Effah, and B. A. Assaga, " Machine learning forecasting of solar PV production using single and hybrid models over different time horizons," Heliyon, Vol. 10, p. e28898, 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).