Introduction

Income inequality is a characteristic social problem of the 21st century, and its public health implications are more visible than ever. As public health approaches have been centered on individuals' behaviors and the availability of health care, mounting empirical evidence suggests a more fundamental driver: income inequality and opportunity imbalance. This essay uses a multilevel analysis from US states in cross-national and global contexts to examine whether income inequality negatively impacts public health.

Braveman and Gottlieb (2014) contend that health outcomes are influenced by “the causes of the causes,” which they call the social determinants of health—conditions that stem from economic and social policy leading to disparities in housing, education, employment, and healthcare. These determinants are ultimately shaped by income inequality, resulting in environments of disadvantage restricting individuals' well-being and community well-being.

Marmot (2005) also shares this perspective, underlining the social gradient nature of health inequalities, i.e., worsening health at all rungs down the income ladder. These inequalities are not determined but are instead socially created and preventable. His research underscores how societies with more inequalities experience poorer overall health within the poorest and all groups at all levels.

By analyzing how income inequality links with health at national and sub-national levels and internationally, this essay seeks to show that it is more than simply an economic problem but a public health emergency demanding structural solutions.

Section 1: Relationship Between Income Inequality and Health Outcomes

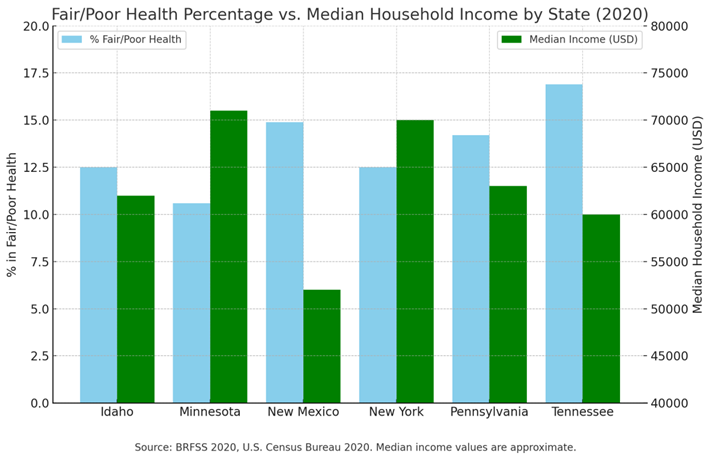

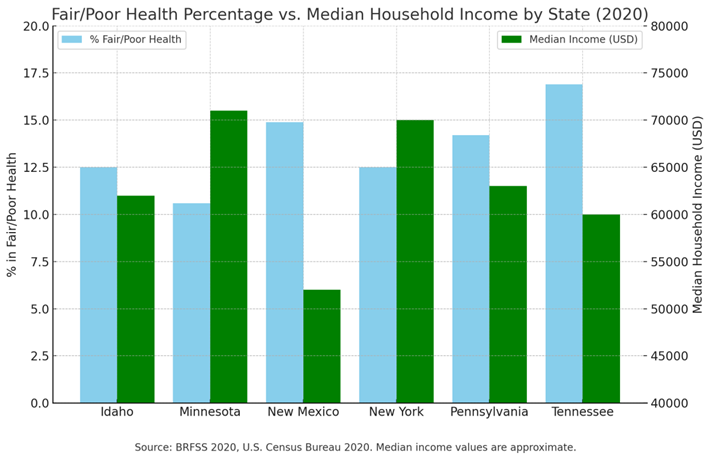

Consistent evidence from epidemiologic studies establishes a link between lower income levels and poorer health, with higher rates of self-rated fair or poor health. Cross-state comparisons between income levels and health are one method for viewing this trend. When using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2020, a bar graph comparing six US states—Idaho, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee—displays a strong inverse correlation between median family income and percentage of fair/poor health reports can be found.

More affluent states, including Minnesota ($71,000) and New York ($70,000), have lower fair or poor health rates at 10.6% and 12.5%, respectively. States with lower incomes, including New Mexico ($52,000) and Tennessee ($60,000), have significantly higher rates at 14.9% and 16.9%. These trends indicate that populations within lower-income settings experience more material and structural barriers to health maintenance.

These observations are supported by findings from López, Loehrer, and Chang (2016), who proved that more unequal income areas have persistently worse population health, with higher death rates as well as a higher prevalence of chronic diseases. These findings further affirm that income is a central determinant for housing, healthcare, and nutrition-related resources.

Notably, there are outliers. Despite a midrange median income of around $62,000, Idaho has a low fair/poor health rating of only 12.5%. Perhaps this is due to offsetting factors such as more social cohesion, reduced density, or healthier habits. Conversely, a higher-than-projected rate (14.2%) in Pennsylvania, even with a similar income level ($63,000), implies other factors—aging population, area-level variation in healthcare infrastructure, or industrial decline—could be behind worse outcomes.

Curran and Mahutga (2018) further highlight that economic inequality impacts material conditions, leading to chronic stress and relative deprivation in societal environments. These psychosocial stressors engage biological pathways for stress, contributing towards mental as well as physical health worsening even in affluent societies. The observation across countries strengthens the premise that economic inequality places a health burden on poorer populations and the socioeconomic gradient as a whole.

Overall, this bar graph reflects a definite—albeit not absolute—correlation between population health and median income. Idaho and Pennsylvania are examples of exceptions, demonstrating that income is not all-determining, yet overall, there is evidence supporting the argument that income disparity plays an important factor in public health inequalities. Structural reform to address these inequalities will be needed to enhance health system access, reduce stress-causing conditions, and provide more equitable health systems.

Table 1.

Fair/Poor Health % vs. Median Income.

Table 1.

Fair/Poor Health % vs. Median Income.

| State |

% Fair/Poor Health (BRFSS 2020) |

Median Household Income (2020) |

| Idaho |

12.5% |

~$62,000 |

| Minnesota |

10.6% |

~$71,000 |

| New Mexico |

14.9% |

~$52,000 |

| New York |

12.5% |

~$70,000 |

| Pennsylvania |

14.2% |

~$63,000 |

| Tennessee |

16.9% |

~$60,000 |

This chart compares the median household income and percentage of adults with fair or poor health in six US states in 2020: Idaho, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee. These data show a strong inverse relationship between income level and health outcomes. States with higher medians, such as Minnesota ($71,000) and New York ($70,000), have lower fair or poor health levels (10.6% and 12.5%, respectively). States with lower incomes, such as New Mexico ($52,000) and Tennessee ($60,000), exhibit significantly higher fair or poor health levels (at 14.9% and 16.9%, respectively). This trend captures how socioeconomic status typically maps to more positive self-assessment health outcomes. There are, however, some significant exceptions visible in this chart. Despite its middle-income level of around $62,000, Idaho still has a poor health level significantly lower than other states, at 12.5%. That suggests other factors, possibly protective health factors, are present. Conversely, Pennsylvania's higher-than-anticipated burden (14.2%) with a median income of just $63,000 evidence other variables, such as healthcare availability, demographics, or geographic disparity. In general, the graph affirms that income is an important determinant for health, albeit not an isolated one, with evidence pointing instead towards a more extensive network of social- and policy-related factors in molding public health between states.

Section 2: County-Level Analysis of Income Inequality in New York State

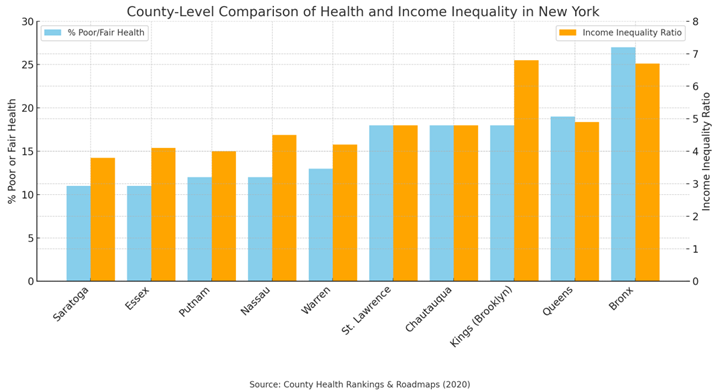

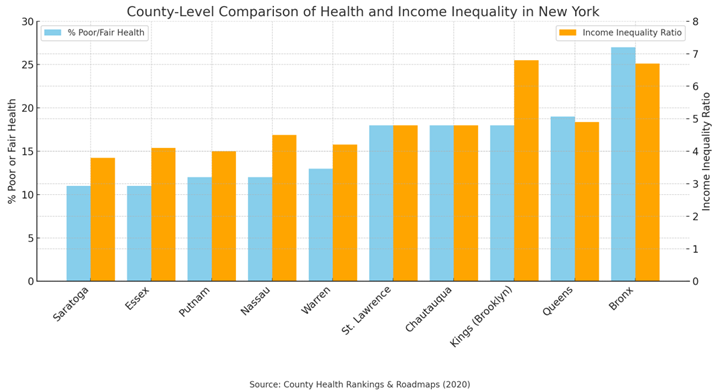

Although state-level comparisons offer a general sense of income inequality’s effects on health, looking more closely at counties demonstrates how this dynamic operates within local neighborhoods. Drawing from 2020 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps data, this section compares ten counties in New York—five with lower percentages of adults with fair or poor health (Saratoga, Essex, Putnam, Nassau, and Warren) with five with higher percentages (St. Lawrence, Chautauqua, Kings, Queens, and the Bronx). When contrasted with each county’s income inequality ratio, it is easy to see a consistent trend: more inequality typically results from more compromised population health. The results show a clear trend: counties with reduced income inequality have better health. Saratoga and Essex, for example, have just 11% living in poor or fair health, with some of the sample's lowest income inequality ratios (3.8, 4.1). Meanwhile, the Bronx and Kings County (Brooklyn) have significantly higher levels of poor health (27% and 18%) as well as more elevated income inequality ratios (6.7, 6.8). These provide evidence for a socioeconomic gradient in health, with inequality at a community level resulting in health disparity between populations.

Kondo et al. (2009) verified this gradient in a meta-analysis of studies with a multilevel approach, demonstrating how people living in high-inequality environments are more likely to be in poor health and die prematurely. Importantly, these impacts do not stop at the poorest quintile but affect the whole population somewhat from inequality-induced social stress.

Svalestuen (2022) adds further insight by examining the mediating function of psychosocial stress. According to their findings, in more economically disparate counties, people are subjected to higher levels of social comparison, economic concern, and lower levels of trust—drivers of enhanced chronic stress, as well as poor physical as well as mental health.

Bai et al. (2023) offer further insight by analyzing how socioeconomic and spatial factors impact income distribution within New York City. They note how income is determined by public transit availability, population density, and school infrastructure—factors similarly impacting health equity. In counties such as the Bronx and Kings, systemic underinvestment coupled with spatial segregation drives increased income inequality and poorer health outcomes, underlining the necessity of looking at spatial factors in addition to measures of income.

Although outliers such as Nassau County (12% poor health, inequality ratio 4.5) would seem to break from this trend, these exceptions can be explained through factors such as greater healthcare access, educational achievement, or upward mobility opportunities. A broad trend is evident: local income inequality powerfully predicts community health. To address this, place-based public health interventions reduce disparities in healthcare access, educational attainment, employment, and resources at the community level.

This bar graph shows how income inequality (in terms of income inequality ratio) relates to the proportion of adults with poor or fair health in 10 counties in New York.

Table 2.

Health vs. Income Inequality – New York Counties (2020).

Table 2.

Health vs. Income Inequality – New York Counties (2020).

| County (NY) |

% in Poor or Fair Health |

Income Inequality Ratio |

| Saratoga |

11% |

3.8 |

| Essex |

11% |

4.1 |

| Putnam |

12% |

4.0 |

| Nassau |

12% |

4.5 |

| Warren |

13% |

4.2 |

| St. Lawrence |

18% |

4.8 |

| Chautauqua |

18% |

4.8 |

| Kings (Brooklyn) |

18% |

6.8 |

| Queens |

19% |

4.9 |

| Bronx |

27% |

6.7 |

This bar chart illustrates the relationship between income inequality (measured by the income inequality ratio) and the percentage of adults reporting poor or fair health across 10 New York counties. A clear pattern is evident: more income inequality—represented by counties like the Bronx (6.7) and Kings/Brooklyn (6.8)—is associated with worse population health (27% and 18%, respectively). Conversely, counties with lower inequality ratios, such as Saratoga (3.8), Essex (4.1), and Putnam (4.0), show better health, with only 11–12% with poor health. Whereas the trend is strong in suggesting worsening population health with increasing income inequality, within-county fluctuations, as with Nassau (4.5 inequality ratio, 12% poor health), underscore the contribution of other factors, including healthcare availability, urban environment and social structure.

Section 3: International Evidence

Increasing evidence from international research establishes that inequalities in income have far-reaching public health effects on individuals' well-being and societal cohesion. In his TED Talk, Wilkinson (2011) provides convincing evidence demonstrating that more unequal countries have higher rates of mental illness, violence, obesity, and imprisonment, with lower rates of trust and social cohesion. These adverse outcomes are not attributable to national wealth but population income inequalities. Even in wealthy countries, individuals with a lower social standing have poorer health outcomes due to ongoing stress from social comparison.

Complementing Wilkinson’s findings, Peters and Jetten (2023) show how inequality conditions psychological functioning. In societies characterized by inequality, people are more inclined to feel anxious, mistrustful, and preoccupied with status—precursors for protracted levels of stress, resulting in heightened cortisol levels, with elevated risks for depression, cardiovascular diseases, and compromised immunities. Such research reiterates how inequality disrupts social and biological pathways underpinning population health.

Millward-Hopkins (2022) includes a world perspective, illustrating how even low levels of inequality cause it to take more energy to achieve decent living standards. In extreme conditions—when there are elites who are ultra-rich—inequality promotes unsustainable consumption, robbing public goods and leading to environmental degradation. These environmental stressors disproportionately hit lower-income people, worsening health inequities globally.

Kondo et al. (2009) reinforce this evidence further by presenting evidence illustrating how psychosocial stress associated with low social standing is tied to higher mortality and poorer health rated by individuals across nations. Their research presents a biological pathway through which inequality is realized in health outcomes.

All these sources together show that economic growth is not enough. High-GDP countries can still have poorer health even if income is not evenly divided. Eradicating inequality with universal health coverage, progressive taxation, and more robust social safety nets is not merely a question of justice—it is key to sustainable, equitable health outcomes worldwide.

Section 4: Fostering Inclusion and Equity in Public Health

Tackling income inequality as a predictor of public health requires acknowledging economic disparities and the intentional application of equity-oriented strategies within health systems. Decades' worth of evidence substantiates how public health outcomes are influenced by the social determinants of health—education, housing, employment, and community conditions—over medical care.

As Robert and Booske (2011) assert, healthy policy must tackle these more comprehensive social drivers to impact population health significantly. More recent trends with the COVID-19 pandemic further illustrated how health inequities are amplified. Burton and Pinto (2023) state that decreasing disparities depends on diversity of thought, experience, and approach in health delivery. Their research emphasizes culturally responsive care, community-informed program development, and responsive interventions considering patients' experiences. These factors are crucial in serving historically disadvantaged populations whose barriers involve transportation, discrimination, and limited digital availability.

Williams, Silvera, and Lemak (2022) extend this reasoning by articulating organizational strategies supportive of equity. They include commitment from leaders in inclusive values, data-driven health outcome audits, and ongoing quality improvement grounded in equity measures. Equity audits are strong tools, enabling healthcare organizations to uncover and address policy-driven disparities, making matters worse.

Combined with community involvement and open reportage, these audits can build an equitable public health system for all groups. Improving public health through promoting equity and inclusion is not a choice but a key factor in ending income inequality and poor health. Social programs and health prevention measures include enrolling more people in Medicaid, strengthening income security, and investing in housing and education. Incorporating equity into policy and practice allows marginalized individuals to achieve a just chance at healthy living through access to health services.

Conclusions

This essay has demonstrated that income inequality is a profound and consistent determinant of poor public health across local, national, and global contexts. Across U.S. states, within counties in states such as New York, and cross-nationally, evidence reveals that with increasing income inequality, so does health disparity. Chronic stress, reduced access to healthcare and social services, as well as systematic underinvestment in marginalized communities are all pathways through which inequality damages population health.

Even within high-income areas, the presence of social stratification has negative effects on physical as well as mental health in all parts of the socioeconomic spectrum. The message is clear: reducing public health disparities involves more than treating illness—it involves structural change. Policies must be centered on equity through expanded Medicaid and public health coverage, investment in affordable housing and early education, enforcement of protections for living wage, and equity audits in health institutions.

As Wilkinson has documented, equality fosters trust, social cohesion, and resilience—necessary for public health and well-being. Public health is not sustainable where there are extreme economic disparities. However, healthy equity can only be achieved if we address the inequalities' deeper causes—through evidence-based, inclusive, and community-driven policy.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this study.

Ethical Statement

This study did not involve human or animal subjects; hence, ethical approval was not required.

Consent Statement

This is not applicable as the study does not involve individual participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

-

Bai, R., Lam, J. C. K., & Li, V. O. K. (2023). What dictates income in New York City? SHAP analysis of income estimation based on Socio-economic and Spatial Information Gaussian Processes (SSIG). Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 60. [CrossRef]

-

Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl 2), 19–31. [CrossRef]

-

Burton, C. W., & Pinto, M. D. (2023). Health equity, diversity, and inclusion: Fundamental considerations for improving patient care. Clinical Nursing Research, 32(1), 3–5. [CrossRef]

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). BRFSS prevalence and trends data. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html.

-

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. (2020). New York State county data. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/health-data/new-york?year=2020&measure=Income+inequality&tab=1.

-

Curran, M., & Mahutga, M. C. (2018). Income inequality and population health: A global gradient? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(4), 536–553. [CrossRef]

-

Kondo, N., Sembajwe, G., Kawachi, I., van Dam, R. M., Subramanian, S. V., & Yamagata, Z. (2009). Income inequality, mortality, and self rated health: Meta-analysis of multilevel studies. BMJ, 339, b4471. [CrossRef]

-

López, D. B., Loehrer, A. P., & Chang, D. C. (2016). Impact of income inequality on the nation’s health. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 223(4), 587–594. [CrossRef]

-

Marmot, M. (2005). Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet, 365(9464), 1099–1104. [CrossRef]

-

Millward-Hopkins, J. (2022). Inequality can double the energy required to secure universal decent living. Nature Communications, 13(1), 5028. [CrossRef]

-

Peters, K., & Jetten, J. (2023). How living in economically unequal societies shapes our minds and our social lives. British Journal of Psychology, 114(2), 515–531. [CrossRef]

-

Robert, S. A., & Booske, B. C. (2011). US opinions on health determinants and social policy as health policy. American Journal of Public Health, 101(9), 1655–1663. [CrossRef]

-

Svalestuen, S. (2022). Is the mediating effect of psychosocial stress on the income–health relationship moderated by income inequality? SSM - Population Health, 20, 101302. [CrossRef]

-

Wilkinson, R. (2011). How economic inequality harms societies [Video]. TED Talks. http://www.ted.com/talks/richard_wilkinson?language=en.

-

Williams, J. H., Silvera, G. A., & Lemak, C. H. (2022). Learning through diversity: Creating a virtuous cycle of health equity in health care organizations. In S. M. Shortell, L. R. Burns, & J. L. Hefner (Eds.), Responding to the Grand Challenges in Health Care via Organizational Innovation (Vol. 21, pp. 167–189). Emerald Publishing. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).