Submitted:

22 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- (1)

- estrogen receptor signaling (ERα, ERβ) in adipose tissue;

- (2)

- intracrine estrogen metabolism via aromatase, 17β-HSD1, and 17β-HSD2 enzymes;

- (3)

- the role of menopause-induced estrogen deficiency in adipose tissue dysfunction;

- (4)

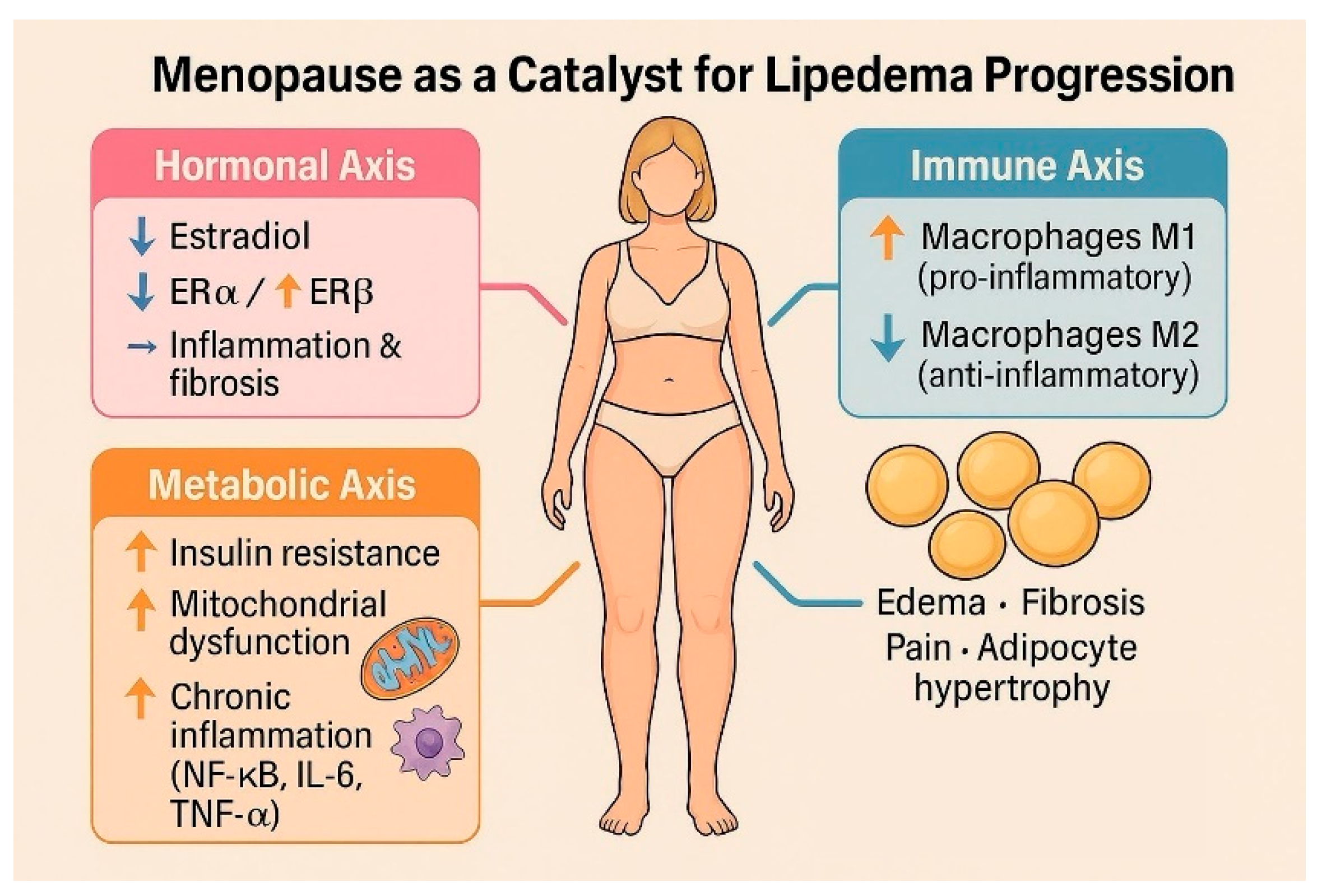

- the immunometabolic consequences of receptor imbalance, including inflammation and fibrosis;

- (5)

- parallels between lipedema and other estrogen-driven gynecological disorders.

3. Discussion

3.1. The Role of Estradiol and Its Receptors

3.2. Intracrine Production of Estradiol in Adipose Tissue

3.3. Progesterone Resistance

3.4. How Menopause Affects Lipedema

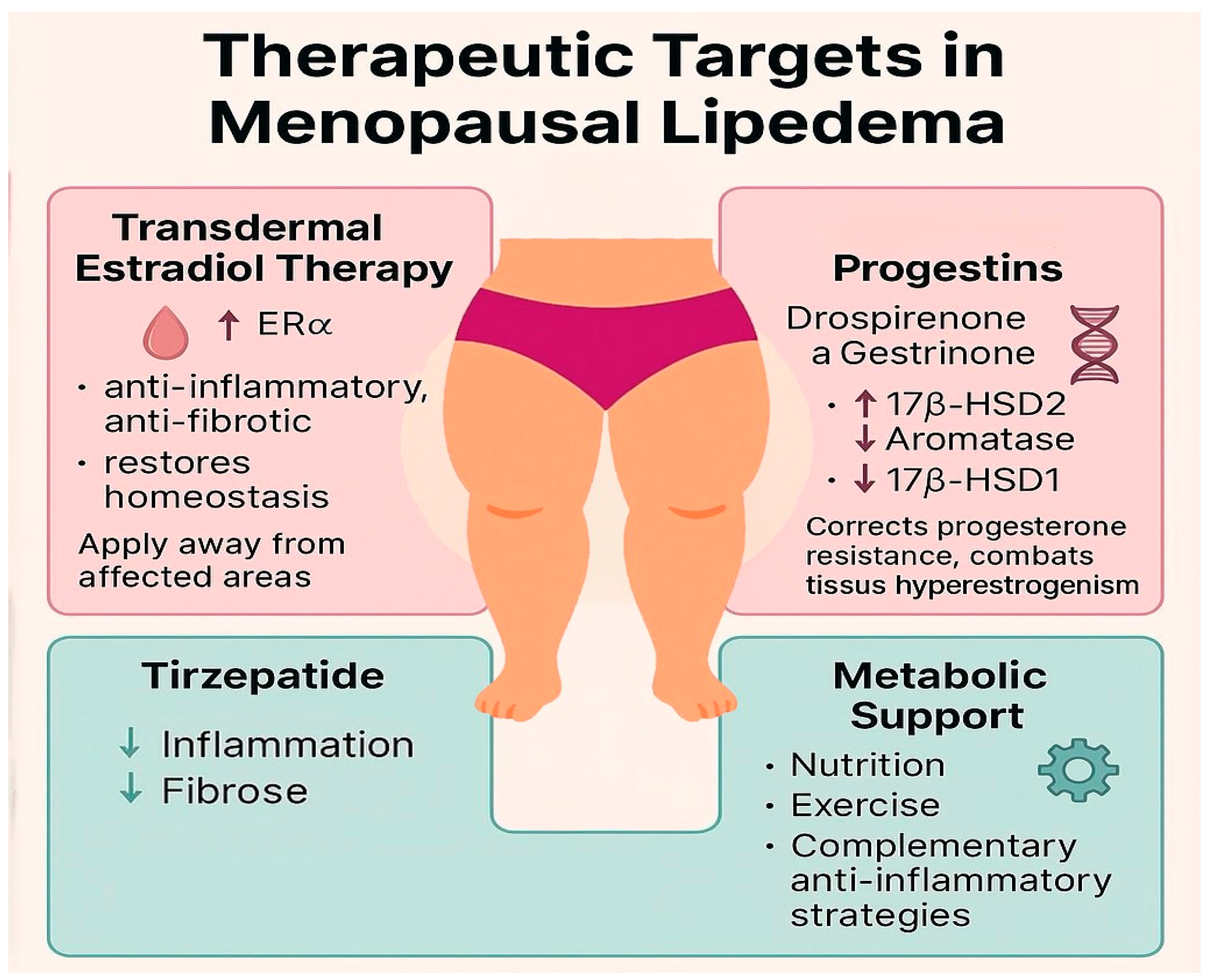

3.5. Therapeutic Implications

4. Conclusions

5. Limitation

References

- Wold LE, Hines EA Jr, Allen EV. Lipedema of the legs; a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema. Ann Intern Med. 1951 May;34(5):1243-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzer K, Hill JL, McIver KB, Foster MT. Lipedema and the Potential Role of Estrogen in Excessive Adipose Tissue Accumulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Oct 29;22(21):11720. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Forner-Cordero I, Szolnoky G, Forner-Cordero A, Kemény L. Lipedema: an overview of its clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of the disproportional fatty deposition syndrome - systematic review. Clin Obes. 2012 Jun;2(3-4):86-95. Epub 2012 Aug 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre YS, Wadeea R, Rosas V, Herbst KL. Lipedema: friend and foe. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2018 Mar 9;33(1):/j/hmbci.2018.33.issue-1/hmbci-2017-0076/hmbci-2017-0076.xml. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santoro N, Sutton-Tyrrell K. The SWAN song: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation's recurring themes. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011 Sep;38(3):417-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Simpson ER, Merrill JC, Hollub AJ, Graham-Lorence S, Mendelson CR. Regulation of estrogen biosynthesis by human adipose cells. Endocr Rev. 1989 May;10(2):136-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, Hodis HN, Johnson AE, Langer RD, Limacher MC, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Allison MA; American Heart Association Prevention Science Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Menopause Transition and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Implications for Timing of Early Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Dec 22;142(25):e506-e532. Epub 2020 Nov 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed F, Kamble PG, Hetty S, Fanni G, Vranic M, Sarsenbayeva A, Kristófi R, Almby K, Svensson MK, Pereira MJ, Eriksson JW. Role of Estrogen and Its Receptors in Adipose Tissue Glucose Metabolism in Pre- and Postmenopausal Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Apr 19;107(5):e1879-e1889. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Foryst-Ludwig A, Kintscher U. Metabolic impact of estrogen signalling through ERalpha and ERbeta. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010 Oct;122(1-3):74-81. Epub 2010 Jul 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szél E, Kemény L, Groma G, Szolnoky G. Pathophysiological dilemmas of lipedema. Med Hypotheses. 2014 Nov;83(5):599-606. Epub 2014 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poojari, A.; Dev, K.; Rabiee, A. Lipedema: Insights into Morphology, Pathophysiology, and Challenges. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3081. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien SN, Welter BH, Mantzke KA, Price TM. Identification of progesterone receptor in human subcutaneous adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Feb;83(2):509-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiSilvestro D, Petrosino J, Aldoori A, Melgar-Bermudez E, Wells A, Ziouzenkova O. Enzymatic intracrine regulation of white adipose tissue. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2014 Jul;19(1):39-55. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Viana DPC, Câmara LC. Hormonal links between lipedema and gynecological disorders: therapeutic roles of gestrinone and drospirenone. J Adv Med Med Res. 2025;37(24):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zeitoun K, Takayama K, Sasano H, Suzuki T, Moghrabi N, Andersson S, Johns A, Meng L, Putman M, Carr B, Bulun SE. Deficient 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 expression in endometriosis: failure to metabolize 17beta-estradiol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Dec;83(12):4474-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke PS, Nanjappa MK, Ko C, Prins GS, Hess RA. Estrogens in male physiology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(2):379–84. [CrossRef]

- Kuryłowicz A. Estrogens in Adipose Tissue Physiology and Obesity-Related Dysfunction. Biomedicines. 2023 Feb 24;11(3):690. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Renke G, Kemen E, Scalabrin P, Braz C, Baesso T, Pereira MB. Cardio-Metabolic Health and HRT in Menopause: Novel Insights in Mitochondrial Biogenesis and RAAS. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2023;19(4):e060223213459. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Geraci A, Calvani R, Ferri E, Marzetti E, Arosio B, Cesari M. Sarcopenia and Menopause: The Role of Estradiol. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021 May 19;12:682012. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang W, Jiang W, Liao W, Yan H, Ai W, Pan Q, Brashear WA, Xu Y, He L, Guo S. An estrogen receptor α-derived peptide improves glucose homeostasis during obesity. Nat Commun. 2024 Apr 22;15(1):3410. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lizcano F, Guzmán G. Estrogen Deficiency and the Origin of Obesity during Menopause. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:757461. Epub 2014 Mar 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC. Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. Diabetes. 2006;55(4):978–87. [CrossRef]

- Tomada I. Lipedema: From Women’s Hormonal Changes to Nutritional Intervention. Endocrines. 2025;6(2):24. [CrossRef]

- Pernoud LE, Gardiner PA, Fraser SD, Dillon-Rossiter K, Dean MM, Schaumberg MA. A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating differences in chronic inflammation and adiposity before and after menopause. Maturitas. 2024 Dec;190:108119. Epub 2024 Sep 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim JH, Cho HT, Kim YJ. The role of estrogen in adipose tissue metabolism: insights into glucose homeostasis regulation. Endocr J. 2014;61(11):1055-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renke G, Antunes M, Sakata R, Tostes F. Effects, Doses, and Applicability of Gestrinone in Estrogen-Dependent Conditions and Post-Menopausal Women. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Sep 22;17(9):1248. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Makabe T, Koga K, Miyashita M, Takeuchi A, Sue F, Taguchi A, Urata Y, Izumi G, Takamura M, Harada M, Hirata T, Hirota Y, Wada-Hiraike O, Fujii T, Osuga Y. Drospirenone reduces inflammatory cytokines, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) expression in human endometriotic stromal cells. J Reprod Immunol. 2017 Feb;119:44-48. Epub 2016 Dec 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprio M, Antelmi A, Chetrite G, Muscat A, Mammi C, Marzolla V, Fabbri A, Zennaro MC, Fève B. Antiadipogenic effects of the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist drospirenone: potential implications for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2011 Jan;152(1):113-25. Epub 2010 Nov 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tankó LB, Christiansen C. Effects of 17beta-oestradiol plus different doses of drospirenone on adipose tissue, adiponectin and atherogenic metabolites in postmenopausal women. J Intern Med. 2005 Dec;258(6):544-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakus, S., et al. (2012). Effects of drospirenone plus estradiol on body fat distribution in postmenopausal women. Climacteric, 15(1), 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Stuenkel CA. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and the Role of Estrogen. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Dec 1;64(4):757-771. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuenkel, C. A., et al. (2015). Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 100(11), 3975–4011. [CrossRef]

- Viana, D. P. C., & Câmara, L. C. (2025, February 28). Metabolic therapy for lipedema: Can tirzepatide overcome the treatment gap? Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International, 37(3), 21–28.

- Jeong, H. G., & Park, H. (2022, October 8). Metabolic disorders in menopause. Metabolites, 12(10), 954. [CrossRef]

- Xia Y, Jin J, Sun Y, Kong X, Shen Z, Yan R, Huang R, Liu X, Xia W, Ma J, Zhu X, Li Q, Ma J. Tirzepatide's role in targeting adipose tissue macrophages to reduce obesity- related inflammation and improve insulin resistance. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024 Dec 25;143(Pt 2):113499. Epub 2024 Oct 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynn TA, Vannella KM. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity. 2016 Mar 15;44(3):450-462. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samms RJ, Zhang G, He W, Ilkayeva O, Droz BA, Bauer SM, Stutsman C, Pirro V, Collins KA, Furber EC, Coskun T, Sloop KW, Brozinick JT, Newgard CB. Tirzepatide induces a thermogenic-like amino acid signature in brown adipose tissue. Mol Metab. 2022 Oct;64:101550. Epub 2022 Jul 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Regmi, A., Aihara, E., Christe, M. E., Varga, G., Beyer, T. P., Ruan, X., Beebe, E., O’Farrell, L. S., Bellinger, M. A., Austin, A. K., Lin, Y., Hu, H., Konkol, D. L., Wojnicki, S., Holland, A. K., Friedrich, J. L., Brown, R. A., Estelle, A. S., Badger, H. S., Gaidosh, G. S., Kooijman, S., Rensen, P. C. N., Coskun, T., Thomas, M. K., & Roell, W. (2024). Tirzepatide modulates the regulation of adipocyte nutrient metabolism through long-acting activation of the GIP receptor. Cell Metabolism, 36(7), 1534–1549.e7.

- Cifarelli V. Lipedema: Progress, Challenges, and the Road Ahead. Obes Rev. 2025 May 27:e13953. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).