1. Introduction

Tungsten is another metal included in the 2023 European Union list of Critical and Strategic Raw Materials (CRM and SRM, respectively), China is the largest producer (86%) of tungsten in the world and the largest supplier (32%) of this metal to the EU [

1]. The strategic importance of this element dates back to era of the first and second world wars, being actually used in tungsten alloy radiation shielding (pure tungsten), military and aerospace applications (tungsten alloys), welding tungsten alloys and jewelry(tungsten carbide), fluorescent lighting (Ca and Mg tungstates), etc.

The main sources for tungsten production are its raw materials: scheelite (CaWO4) and wolframite ((Fe,Mn)WO4), though its recovery is also associated to the presence of these mineral species in cassiterite ores, thus sometimes tungsten is a subproduct of tin industry. Wolframite, together with cassiterite, coltan and gold are known as conflict minerals or 3TG.

Both pyrometallurgical and/or hydrometallurgical processing had been widely considered for the recovery of this element from different sources.

Among recent publications different flowsheets in the treatment of scheelite, wolframite and secondary sources had been reviewed [

2], or description of leaching procedures on scheelite [

3] can be found.

In the recovery of tungsten from secondary sources, the treatment of spent SCR denitration catalyst by Na

2S alkali leaching and calcium precipitation [

4], the recovery of this strategic element from tungsten fine mud [

5], or the recycling of tungsten-filled vinyl-methyl-silicone-based flexible shielding materials via pyrolysis and ultrasonic cleaning procedure [

6] have been considered.

Tungsten scraps were utilized by the production of PTA. In this investigation the scraps were subjected to the following steps: preliminary oxidation of waste tungsten carbide, reduction to intermediate-valence tungsten oxides, and subsequent dissolution in hydrogen peroxide to produce peroxotungstic acid (PTA) [

7].

Waste fluidized catalytic cracking (FCC) catalysts were used to recover Mo and W using a oxidation treatment–alkali roasting–wet mill leaching operational steps [

8].

Real W[sbnd]Ni electroplating wastewater were treated to recover W via acid precipitation, followed by thermal oxidation using sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) to dismantle organic complexes, which facilitates subsequent Ni recovery through alkali precipitation [

9].

With respect to the treatment of tungsten ores, the pyro and hydrometallurgical processing of a wolframite concentrate to recover ammonium paratungstate had been described [

10]. In this work, the use of NaHSO

4·H

2O to roast wolframite, as an alternative to i.e. sodium carbonate, and water leaching of the roasted product served as the base to produce APT.

Scheelite ores had been also the subject of recent investigations aimed to the recovery of tungsten. A series of scientists considered that heap leaching technology has a series of advantages (i.e. minimum operating and capital costs) over agitation leaching. Thus in [

11] the performance of this heap leaching technology has been increased by pelletization of the scheelite ore originating from the Republic of Kazakhstan. A mixture of hydrochloric and oxalic acids are used as leachant for scheelite. Against the above, agitation leaching on a synthetic scheelite sample was investigated using a mixture of sulfuric acid and H

2O

2 to dissolve tungsten [

12].

As an alternative to the different procedures described above, solvent extraction with TBP are used to extract tungsten from sodium tungstate solutions. Further, water stripping can efficiently recover tungsten to produce a metatungstic acid solution [

13].

The present work investigates the recovery of tungsten from three concentrates of Spanish origin. Two of these concentrates contained scheelite or wolframite as main species, whereas the third consisted of a scheelite-wolframite mixture. Different operational procedures are considered for these concentrates, allowing the obtaining of tungstic acid or pure calcium tungstate (synthetic scheelite) as final products, which on the other hand can serve as precursors for the production of other tungsten species (APT, metallic tungsten).

2. Materials and Methods

The concentrates came from a tin deposit located in northwest Spain. The tin ore, after mining operations, was subjected to an electrostatic separation operation. This operation resulted in obtaining tin concentrates and various tungsten-bearing concentrates [

14], whereas the various concentrates used in this work presented the composition showed in

Table 1.

Leaching and precipitation experiments were carried out in a 500 mL glass reactor provided of water reflux, and heated and stirred via a magnetic plate. After filtration of the samples, tungsten was analyzed in the liquid phases by ICP-MS (Perkin Elmer ELAN 6000).

Surface characterization (tungstic acid and synthetic scheelite) was carried out using a scanning electron microscope with field emission gun (FEG-SEM) (Hitachi S 4800), also equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (Oxford Instruments NanoAnalysis). DRX-spectrum was recorded on a Siemens D500 X-ray diffractometer.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Leaching of Wolframite Concentrate

3.1.1. Influence of the Leaching Agent

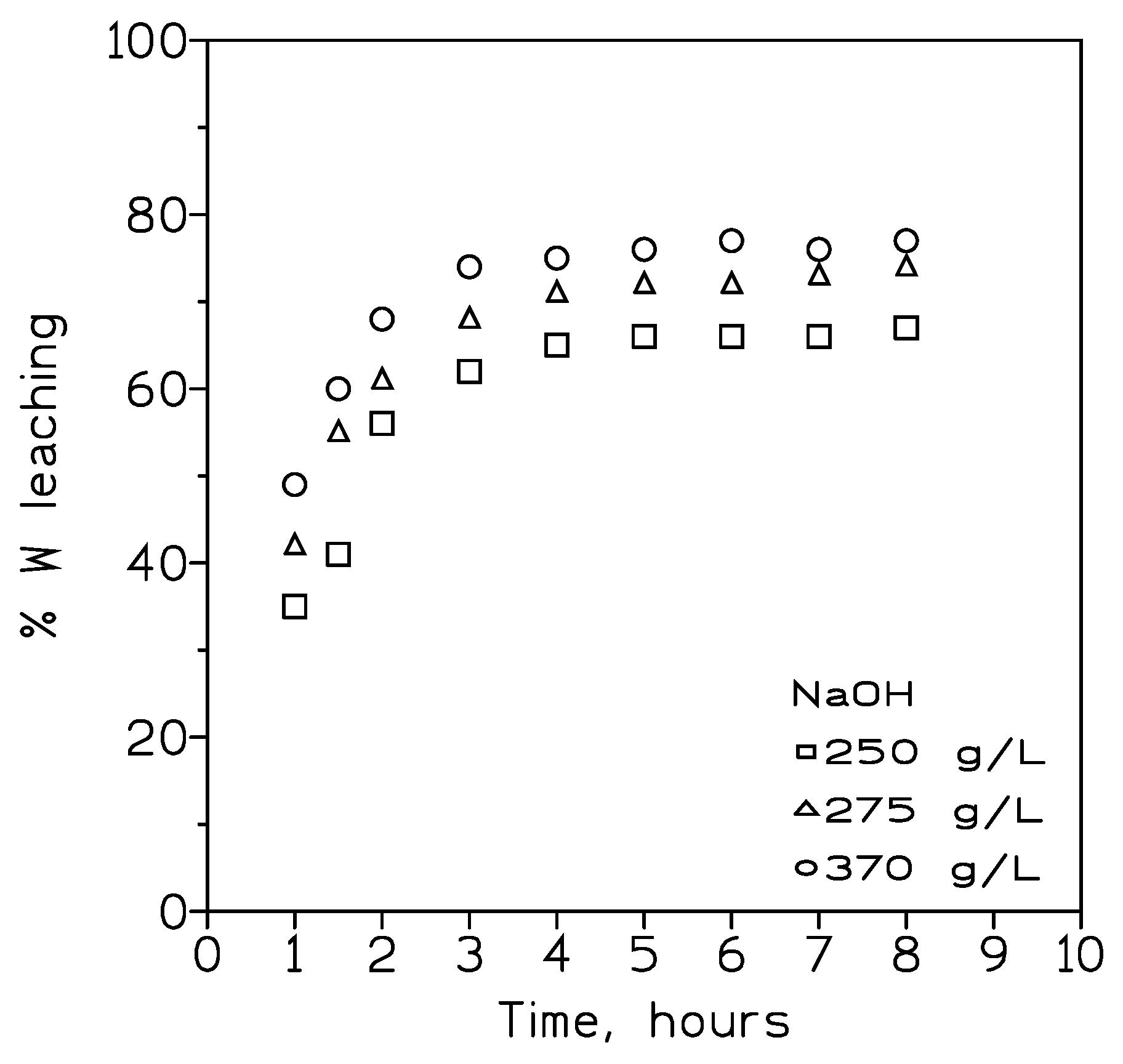

Figure 1 showed the results obtained from the leaching experiments using various NaOH solutions. Results indicated that best tungsten dissolution was reached when the most NaOH concentrated solution (370 g/L) was used in the experiments. As a general rule, a sharp increase in the recovery of tungsten between one and three hours was observed, and after this time the dissolution proceeded smoothly (a mere 5% increase between three and eight hours).

3.1.2. Influence of the Particle Size

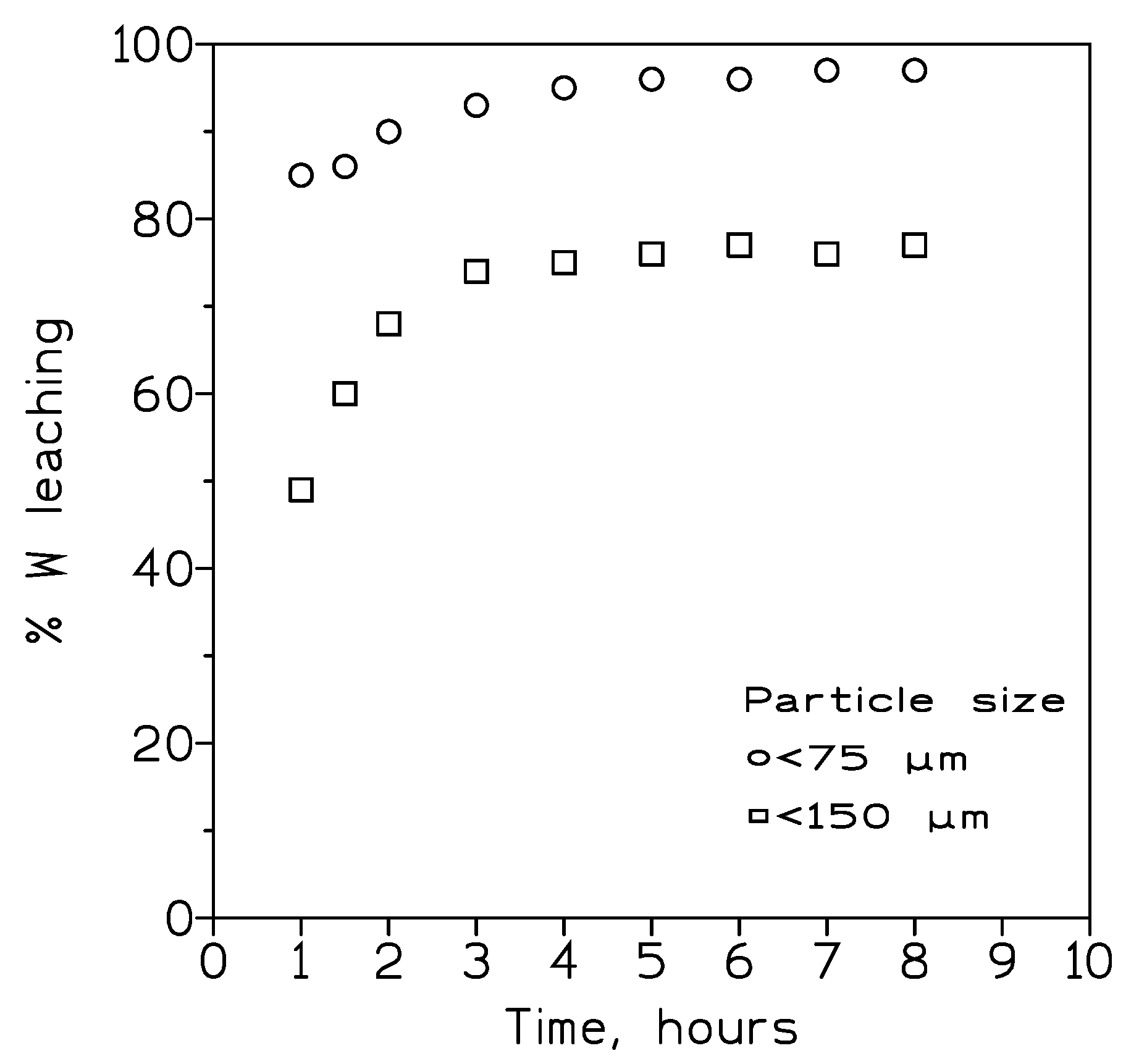

The influence of the particle size on tungsten recovery from the wolframite concentrate was also investigated. In these series of experiments NaOH solution of 370 g/L were used as leachant, whereas the other experimental variables were fixed as in Figure X. The results from this experimetation were shown in

Figure 2. It can be seen that the decrease in the particle size increased the percentage of tungsten dissolution, though leachng rates of at least 95% were only reached after four hours of reaction time.

The reactions responsible for tungsten dissolution are:

Though NaOH in excess is necessary to accomplish the dissolution of this strategic element. From these results it can be concluded that in the recovery of tungsten from the wolframite concentrate the increase of the NaOH concentration in the leaching solution have not an appreciable effect of the rate of leaching. However, the variation of the particles size has a key and positive influence on this leaching rate. Thus, using the lowest particle size one can yield solutions of about 750 g/L Na2WO4, serving as starting point to obtain APT or synthetic scheelite.

3.2. Leaching of the Scheelite Concentrate

3.2.1. Influence of the Temperature on Tungsten Recovery

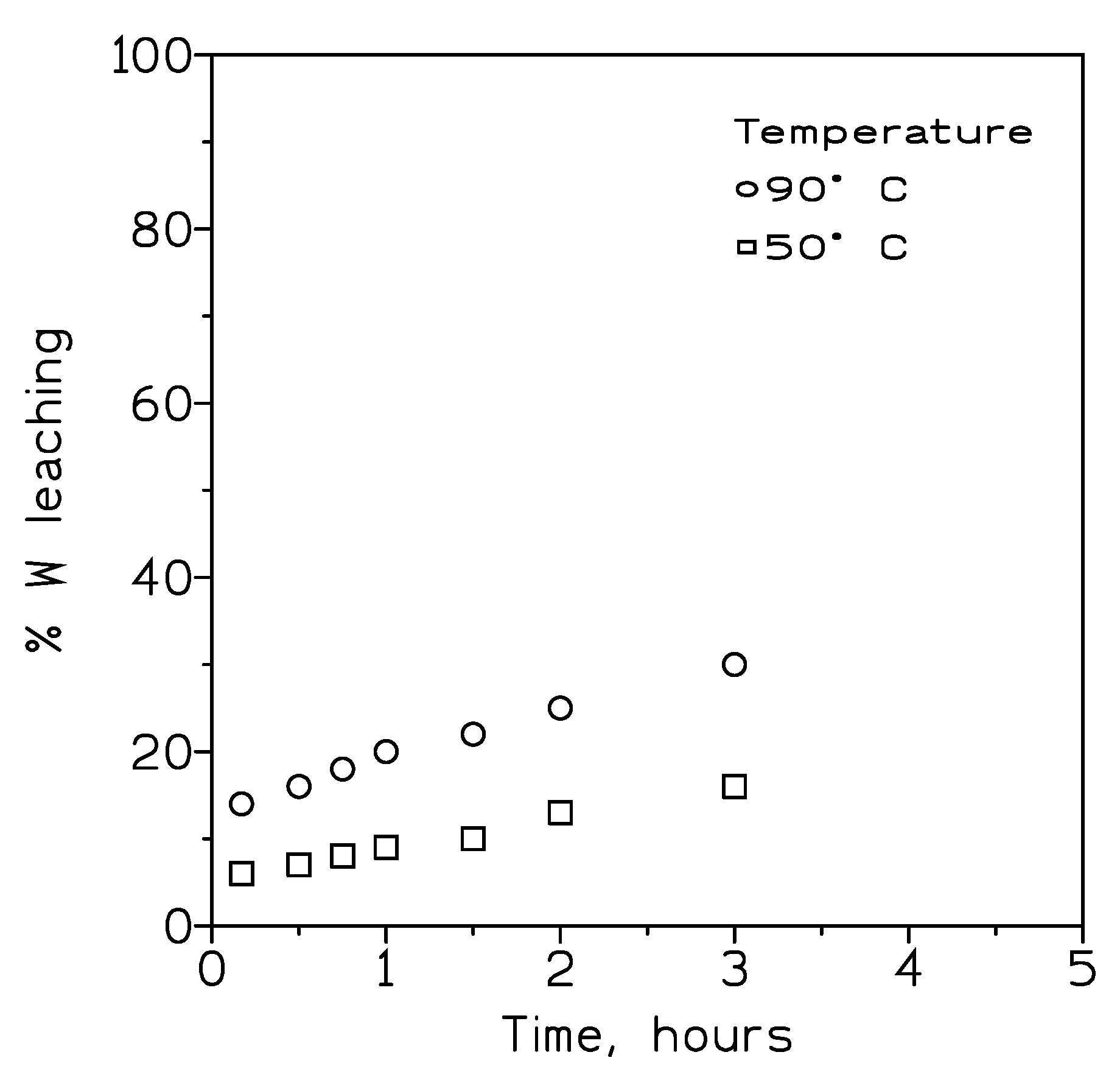

These experiments were carried on samples with <75µm particle size simple, 200 g/L of HCl and 3.2 wt% pulp density. The results of this experimentation were shown in

Figure 3. It can be seen that an increase of the temperature increases the leaching rate, however in all these cases the leaching rate is very low.

3.2.2. Influence of the Particle Size

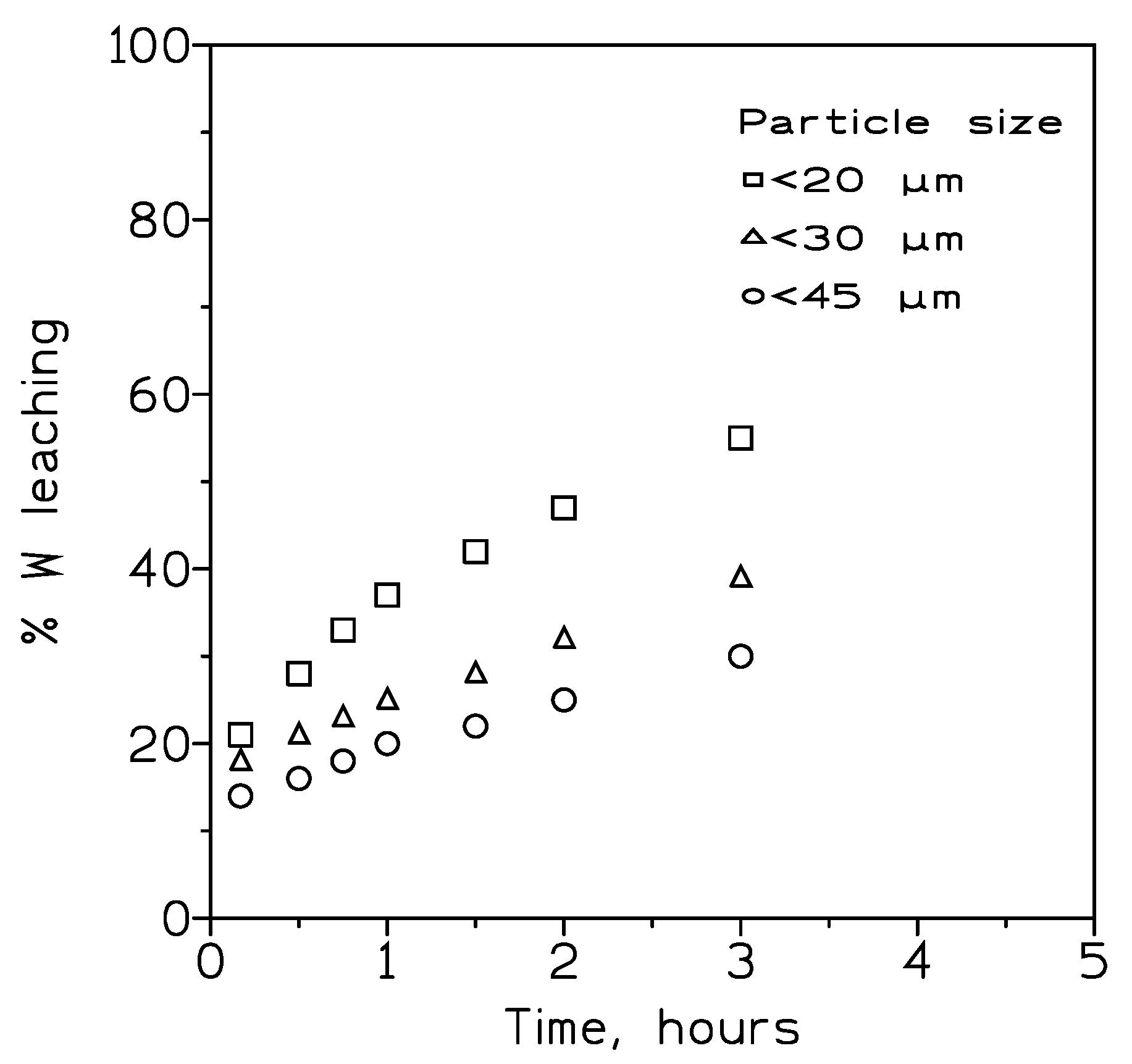

According with it is mentoned above and the results obtained in subsection, the variation of the particle size on tungsten recovery was next investigated at 90º C, and using the other same experimental variables as in

Figure 3. The next

Figure 4 showed the results of these exoeruments.

As in the case of the wolframite concentrate, the variation of the particle size of the scheelite concentrate have a key effect on tungsten recovery. This rate increased with the decrease of the particle size, this influence is more noticeable when longer reaction times are used.

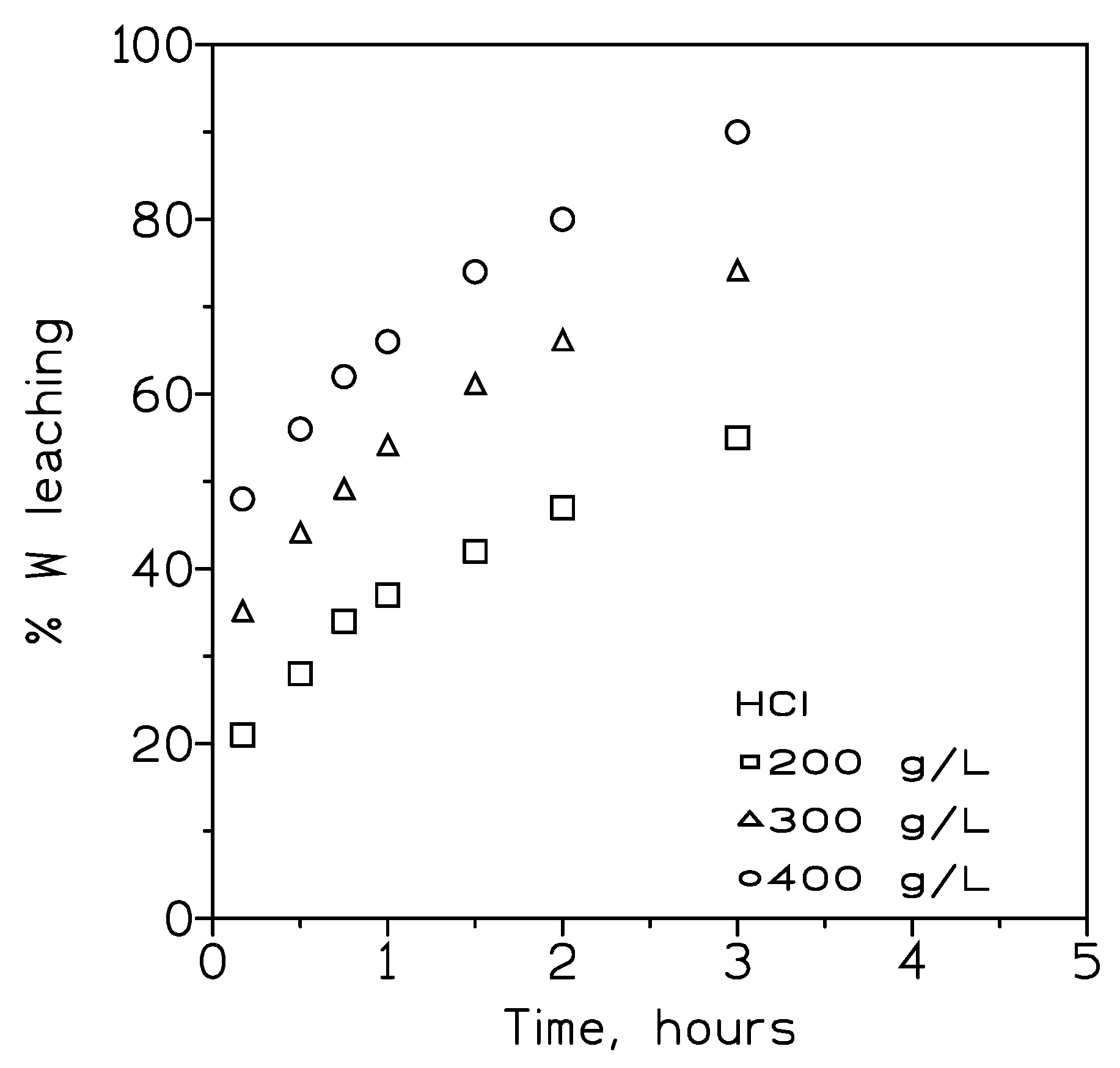

3.2.3. Influence of the Leachant on Tungsten Recovery

In order to gain information about the leaching behavior of this concentrate when different HCl concentrations are used to leach tungsten, a series of experiments were performed on the simple with <38 µm particle size.

Figure 5 showed the results obtained at the various HCl concentrations.

These results indicated that the leaching rate of tungsten increased with the increase of the HCl concentration, with near complete dissolution of the concentrate using 400 g/L HCl as leachant and three hours.

In the case of this concentrate, tungsten dissolves according to the next reaction:

As a general conclusion, the change in temperature is the variable that least affects the tungsten dissolution process from this scheelite concentrate. Similarly to the wolframite concentrate, it is necessary to use an excess of the leachant, in this case HCl, to reach adequate tungsten recoveries from the scheelite concentrate, though in this case the utilization of this excess can be attributed to the formation of a tungstic acid film around the scheelite particle impeding the subsequent attack of the same.

3.3. Leaching of a Scheelite-Wolframite Concentrate. Acidic Medium

3.3.1. Influence of HCl Concentration on Tungsten Leaching

The influence of the HCl concentration on tungsten recovery from the mixed concentrate is shown on

Table 2.

These results show the ineffectiveness of hydrochloric acid for the dissolution of the concentrate. Only in the case of using concentrated acid (12 M) and a high temperature (80º C) is a yield above 50% obtained.

3.3.2. Influence of the Pulp Density on Tungsten Recovery

This variable was also investigated, and the results were summarized in

Table 3.

As in the previous case, the variation of the pulp density did not increase the percentage of tungsten recovered in the solution, on the contrary, the use of more diluted slurries causes the percentage of tungsten recovery to decrease drastically.

3.4. Leaching of a Scheelite-Wolframite Concentrate. Alkaline Medium

Due to the ineffectiveness of the acid attack on the mixed concentrate, experiments were carried out using NaOH solutions. Different pulp densities were used in this experimentation, and the results were summarized in

Table 4.

3.5. Pyro-Hydrometallurgical Treatment of the Mixed Concentrate

Due to the ineffectiveness of the acid and alkaline attacks on the concentrate, a mixed pyro-hydrometallurgical procedure was investigated. As a first step, the concentrate was roasted in sodium carbonate media and various temperatures, the roasted material was further subjected to a leaching procedure using water. The results from these two steps were described below.

3.5.1. Roasting of the Concentration in Sodium Carbonate Media

Table 5 summarized the various experiments carried out on the mixed concentrate.

The reactions occurring during this roasting step are:

In the case of the iron-manganese species, the presence of an oxidant (air) is necessary to achieve the complete oxidation of both metals. In the case of eq. (6), the formation of CaO is undesirable since in the subsequent leaching stage the presence of this oxide can promote the formation of solid scheelite with the subsequent loss of tungsten. This reaction can be avoid by adding silica during the roasting step, so that an insoluble calcium silicate is formed preventing the formation of scheelite.

3.5.2. Leaching of the Roasted Materials

As it is said above, the leaching experiments of the roasted materials were carried out using water as leachant, the influence of the pulp density was investigated.

Table 6 summarized the results from these series of experiments.

These results indicated that to yield better tungsten recoveries it is necessary the use of an excess of sodium carbonate (i.e. 40%) over the stoichiometric reaction and a roasting temperature in excess of 700º C. As a general rule the percentage of tungsten recovery increased with the use of more diluted pulps.

3.6. Treatment of the Leachates

3.6.1. Acidic Medium

The use of an acidic medium as leachant was only effective in the case of the scheelite concentrate (section 3.2.). As a result of this operation, tungstic acid was formed, This compound either precipitates on cooling the filtered solutions or precipitates in the leaching process itself together with the insoluble residue.

In the second case, a purification of the impure tungstic acid is needed, this step included the acid dissolution in ammoniacal (concentrated ammonium hydroxide) and 60º C) or NaOH (50 g7L at room temperature). Further and using as in our case tungstate solutions containing 85 g/L W, re-precipitation of tungstic acid is carried out using 10 M HCl and in excess with respect of the reaction:

Temperature has also an influence in this re-precipitation, high temperature (i.e. 80º C) is beneficial with respect to 25º C. Moreover, the solid obtained at this last temperature has a white color, while that obtained at 80º C has the characteristic yellow color of tungstic acid. The white precipitate contained some impurities, which need to be eliminated by successive washing with dilute acidic (HCl) solutions and/or re-precipitation operations.

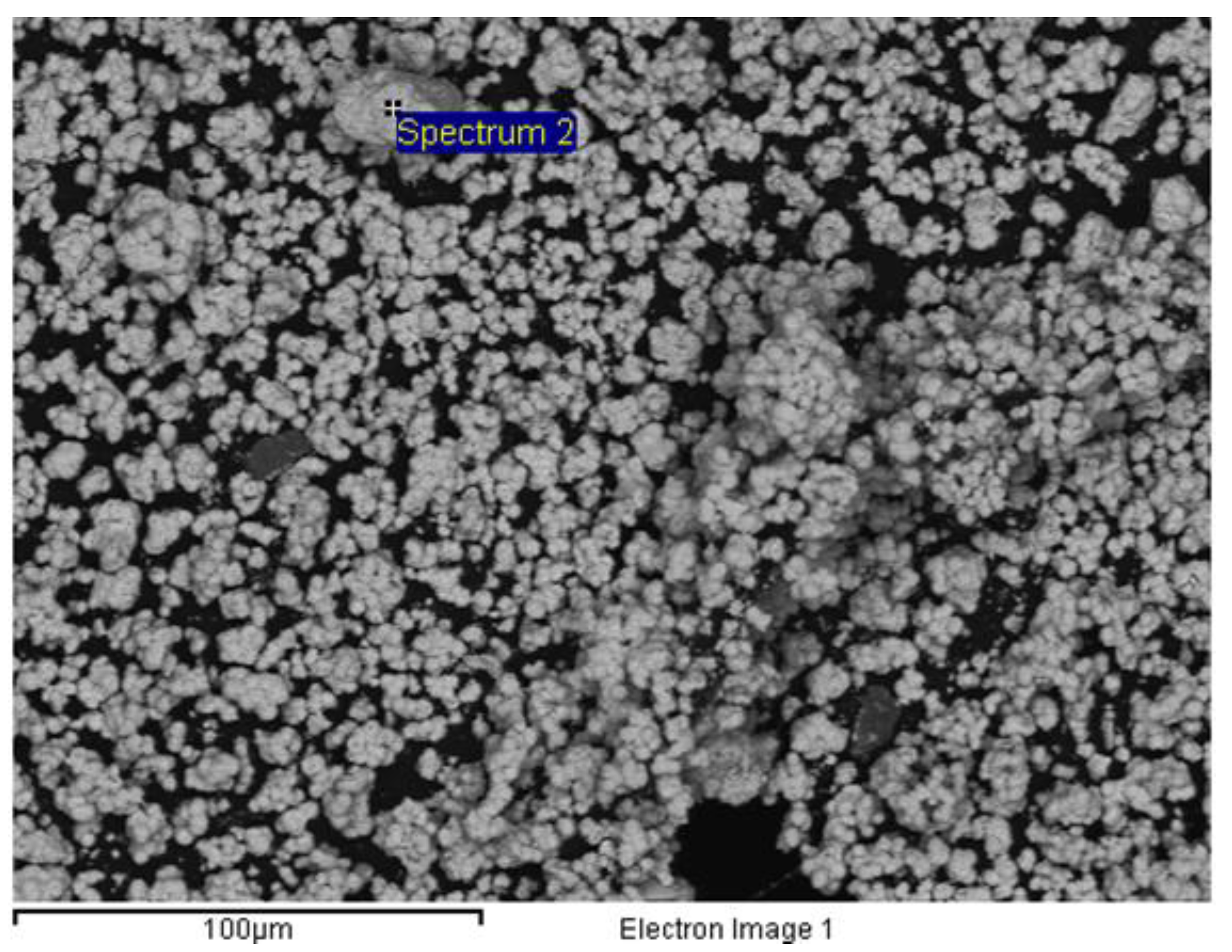

Of the two options discussed at the beginning of this section, the first option, let us recall the precipitation of tungstic acid by cooling the filtered solution after the acid leaching stage, allowed to yield pure yellow tungstic acid. Next

Figure 6 showed a SEM image of the yellow tungstic acid derived from the above procedure.

Finally, the re-precipitation process benefits from adding the hot tungstate solution to the hot HCl medium, and not the other way around. Also, the addition of the tungstate solution at high speed over the HCl solution favors the formation of coarser particles of tungstic acid.

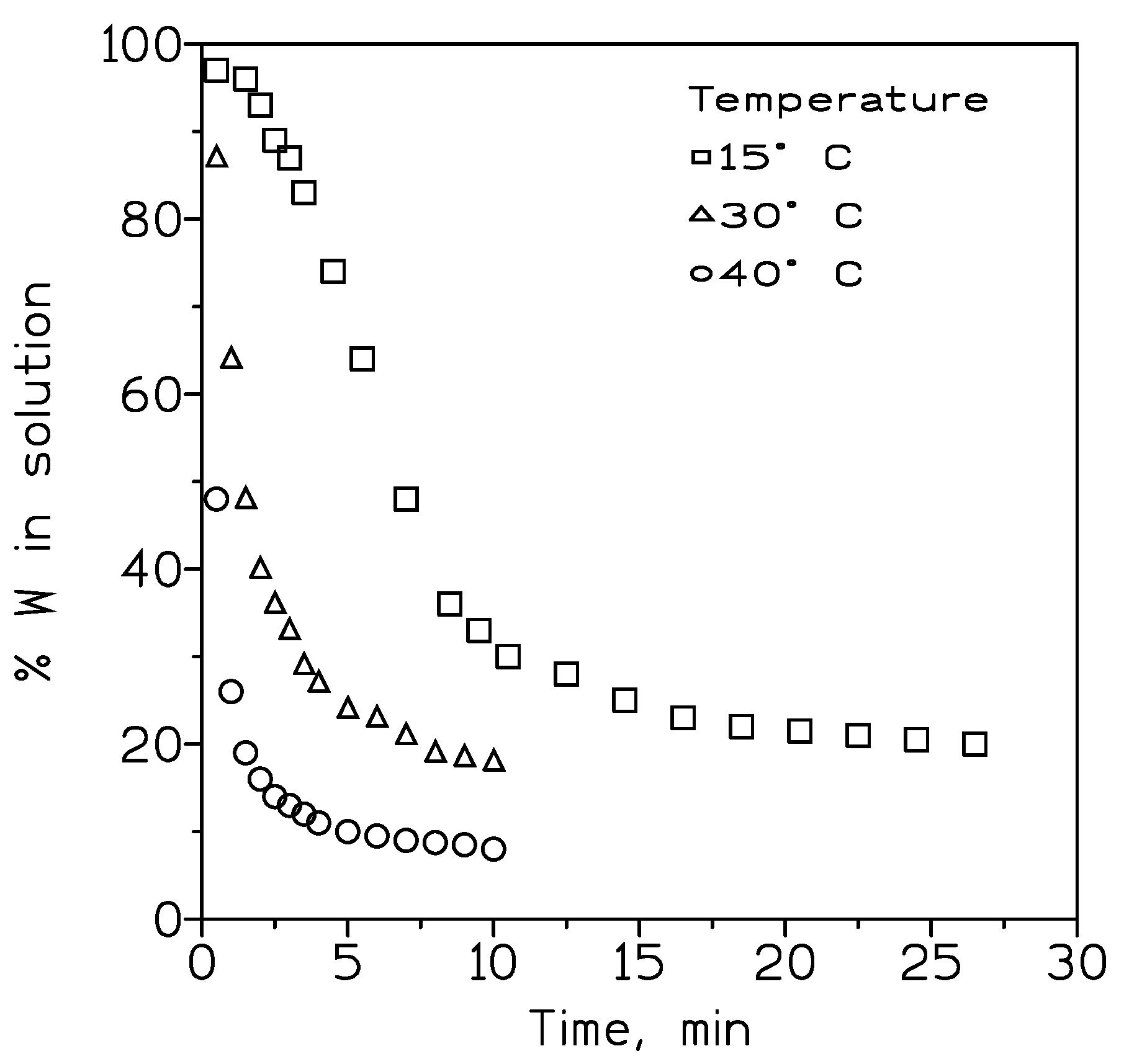

3.6.2. Alkaline Medium

Since the wolframite or the scheelite-wolframite mixture dissolution process yielded alkaline sodium wolframate solutions, the beneficiation process for these solutions included the obtaining of pure calcium tungstate (synthetic scheelite).

In the present investigation and starting from sodium tungstate solutions of about 10 g/L W and pH values greater than 8, the precipitation was experimented using CaCl

2 solutions (though the use of Ca(OH)

2 was also acceptable) following the next reaction:

The precipitation process was carried out at temperatures in the 15-40º C range (

Figure 7), showing that an increase of the temperature favored the removal of tungsten from the solution, and thus, the precipitation of synthetic scheelite.

With respect to the obtaining of this scheelite, the best yields are obtained by maintaining in the tungsten solution always a pH value higher than 8 and by using a concentration of CaCl2 15% higher than that corresponding to the stoichiometry of the previous reaction. A finer particle size solid is obtained by adding the calcium solution on top of the tungsten solution.

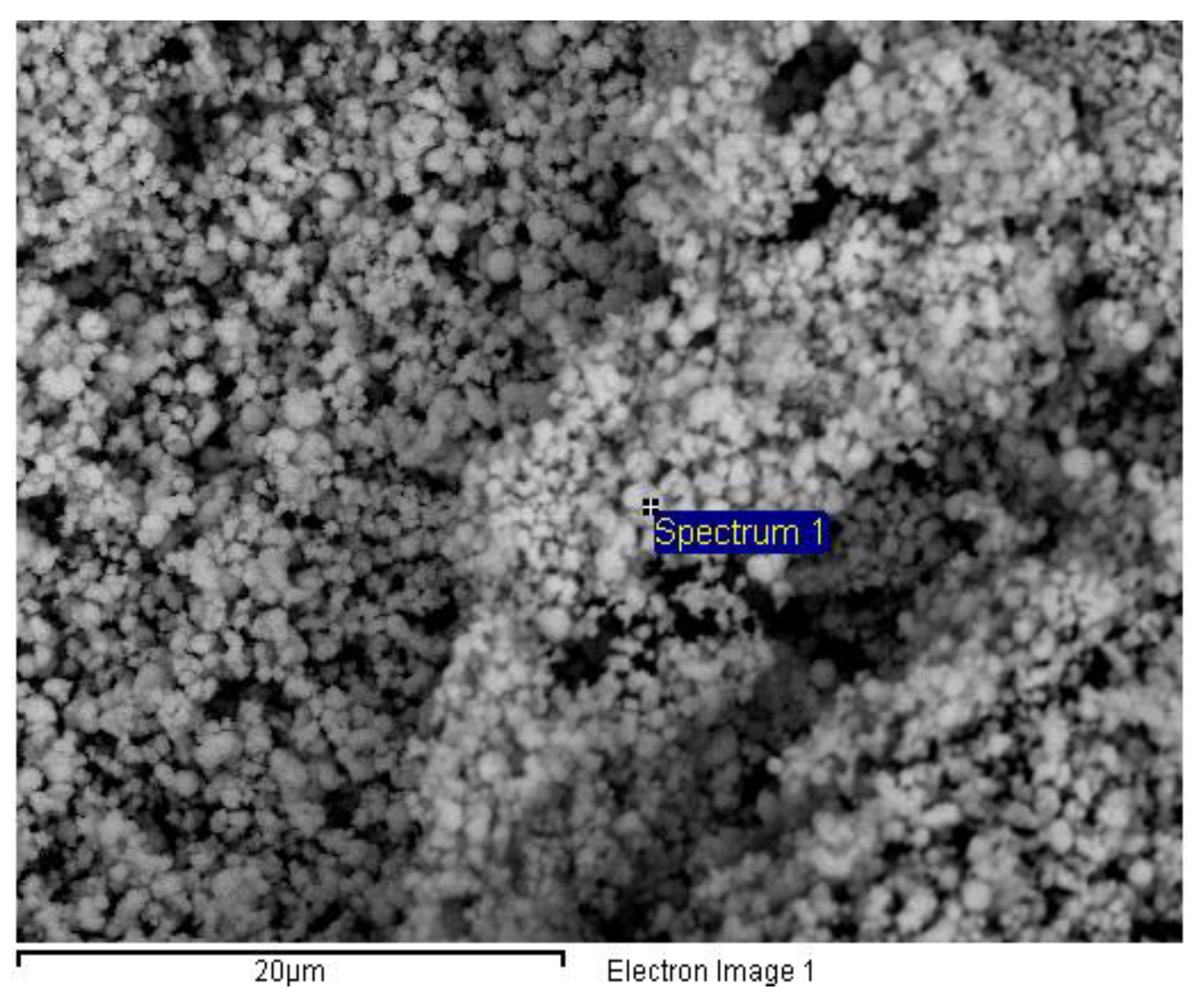

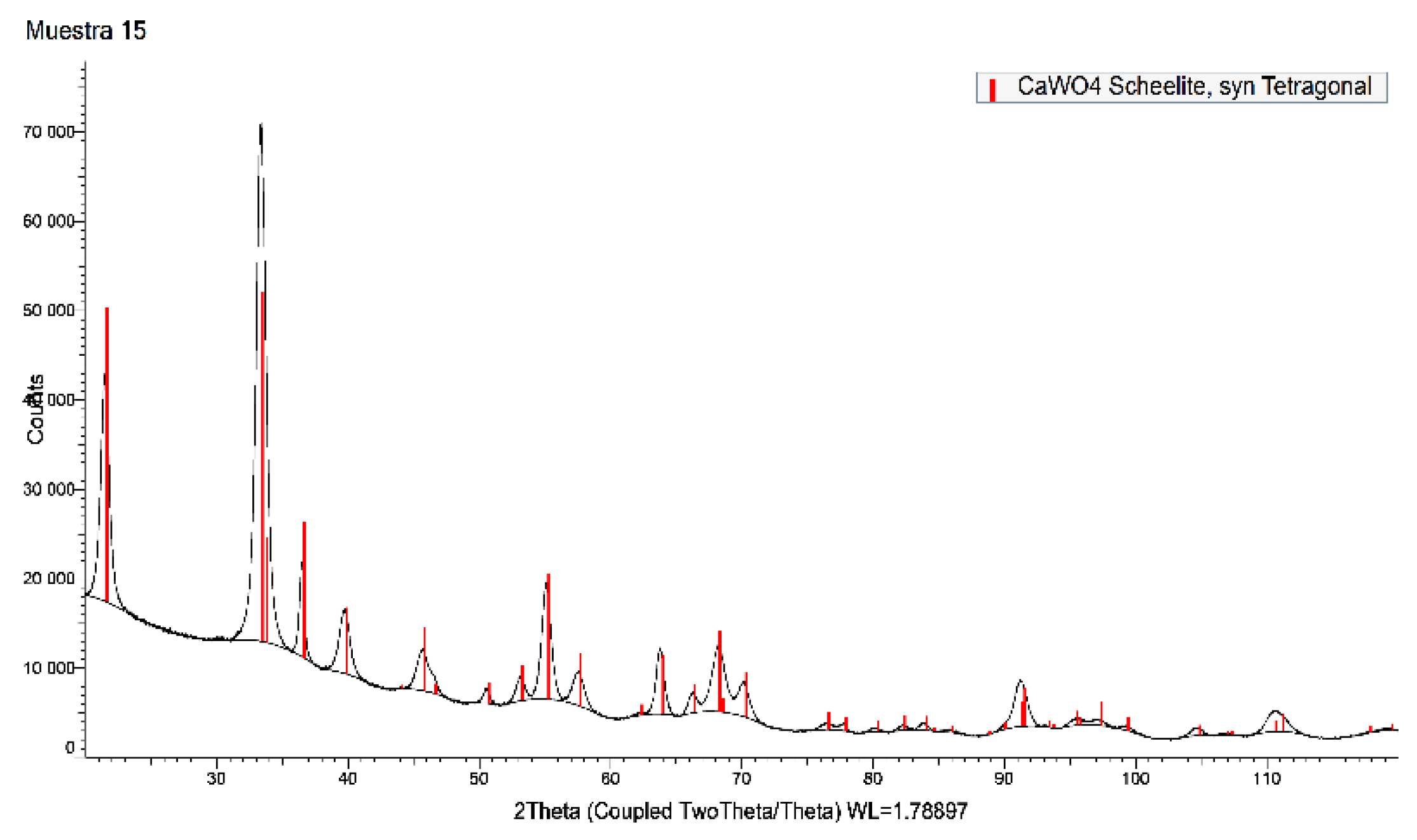

Figure 8 showed a SEM image of the synthetic scheelite obtained at 40º C, whereas

Figure 9 showed the XRD spectrum of the same sample. From this last Figure it can be seen that the solid has crystallized in the tetragonal system.

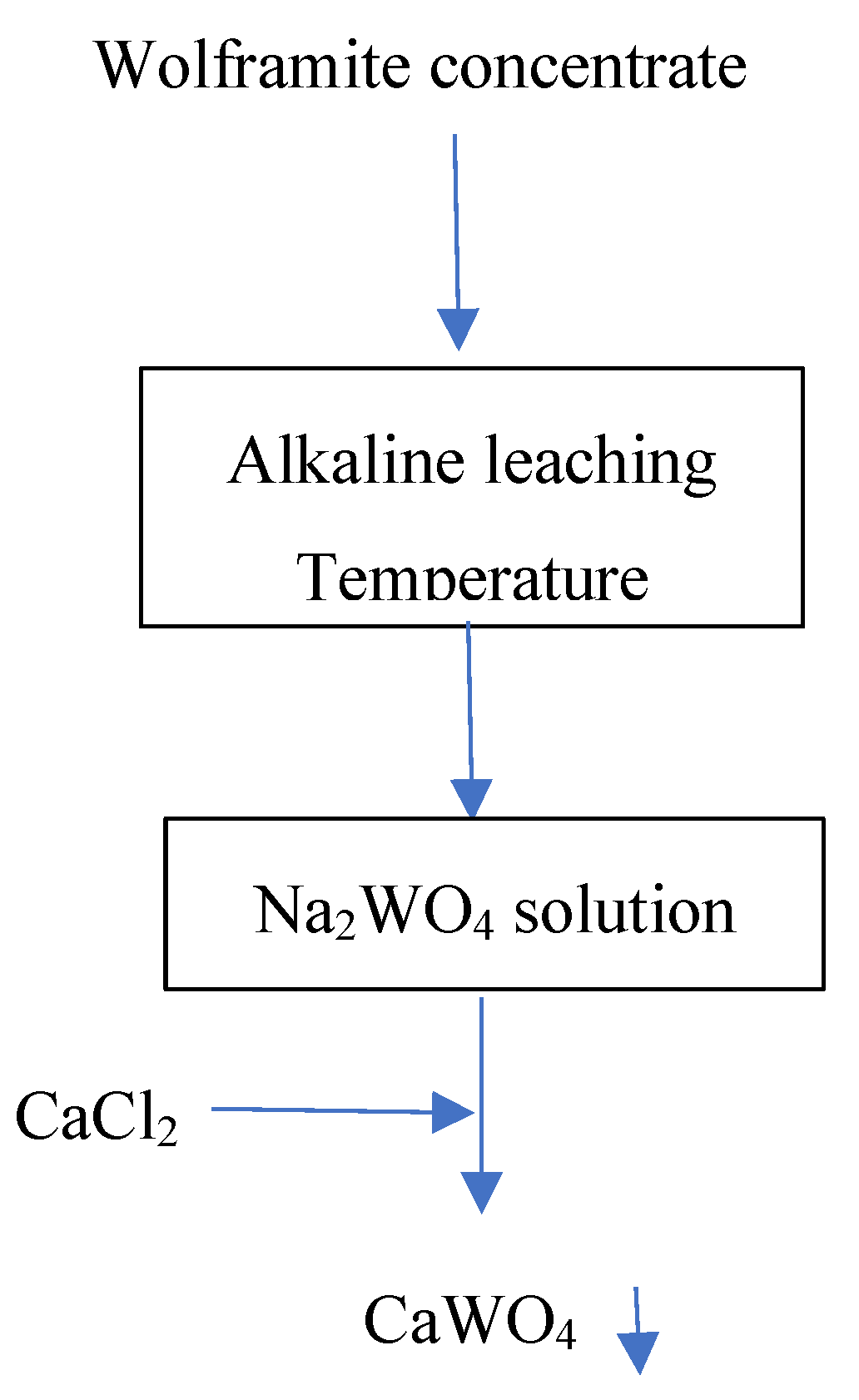

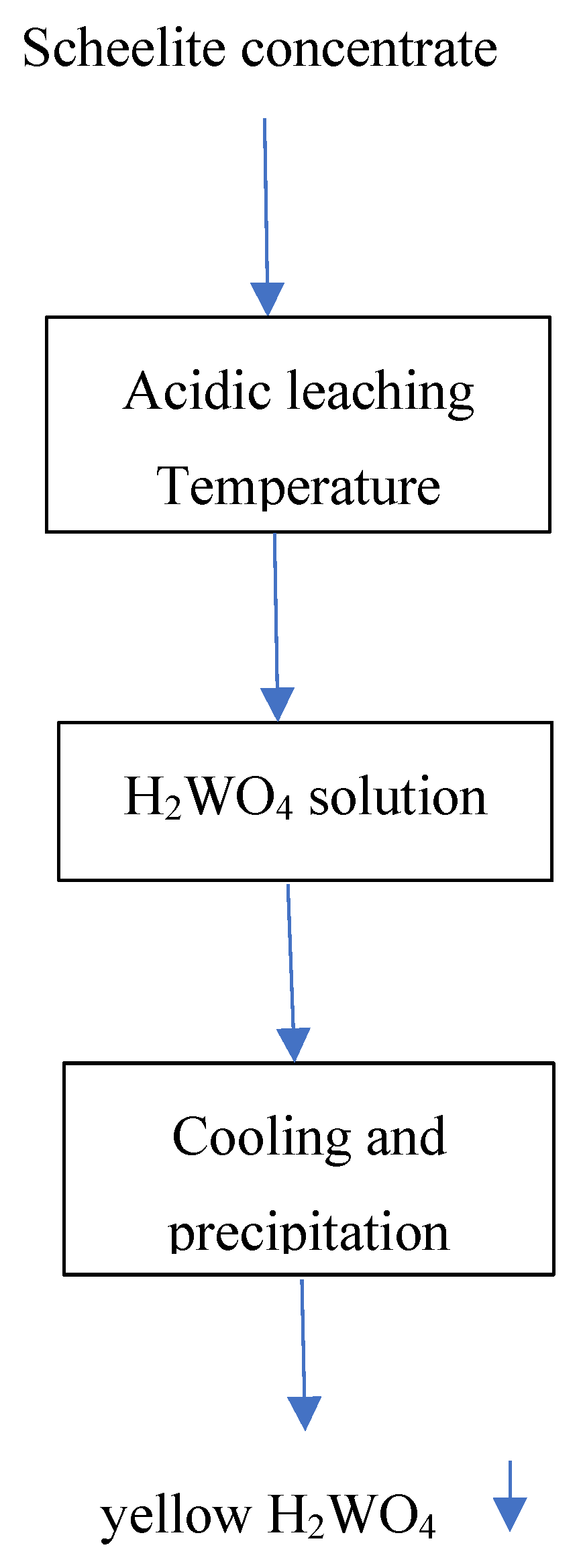

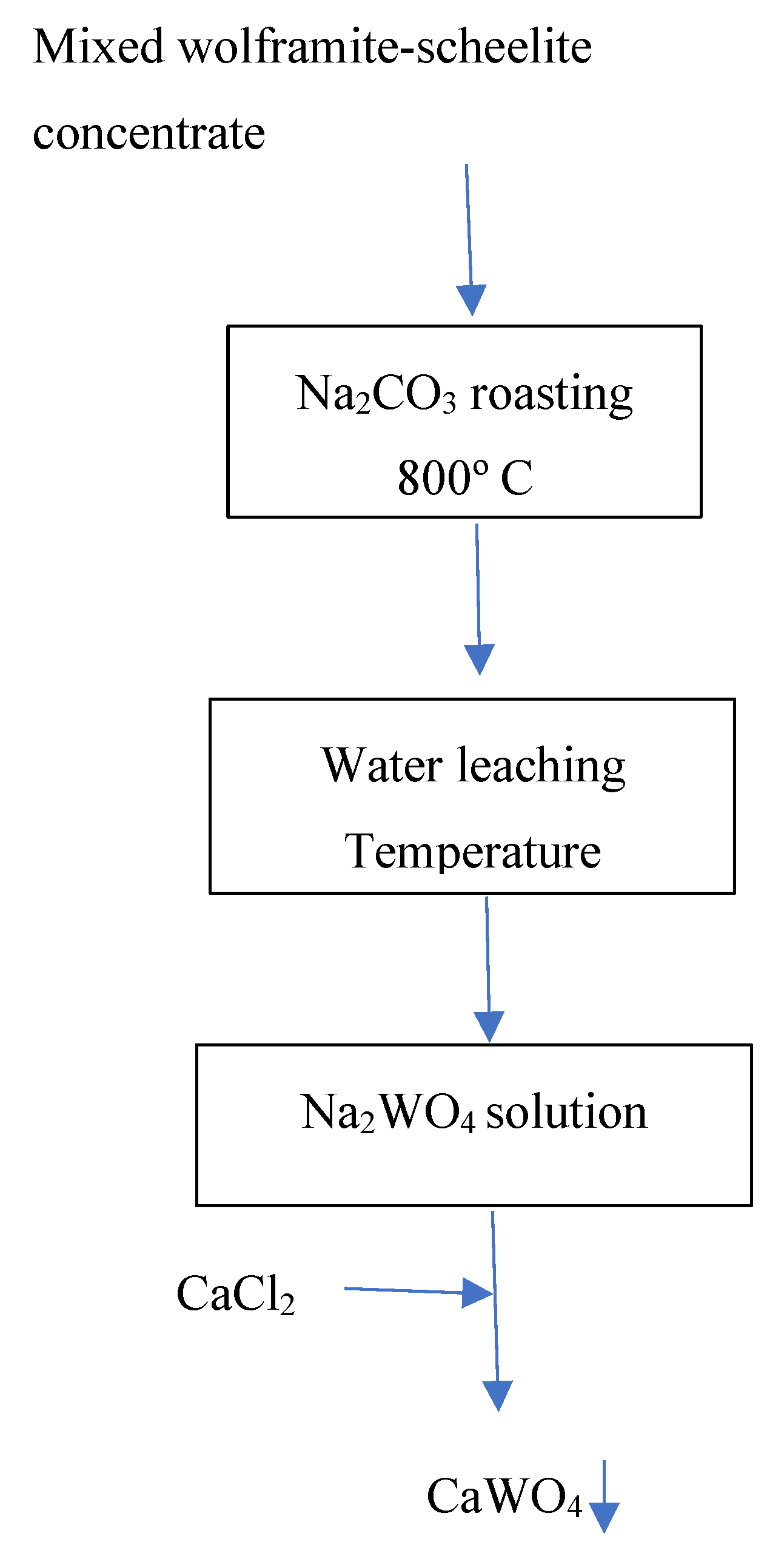

3.7. General Flow-Sheets

Based in the results presented in the previous

Sections, the treatment of each concentrate differs one from another, thus, particular flow-sheets may be generated for each concentrate. These are presented in

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 for wolframite, scheelite and mixed wolframite-scheelite concentrates.

It is worth mentioning that all these schemes are flexible enough to allow the inclusion of stages to improve the quality of the products (especially intermediates). Likewise, the final products (tungstic acid, synthetic scheelite) can be used to obtain other products of interest, such as APT, WO3 or metallic tungsten, though this investigation has not gone to these extremes.

4. Conclusions

In this work we have developed a series of processes to obtain tungsten from concentrates of Spanish origin. The characteristics of these concentrates make these processes differ from each other, the best conditions for obtaining a pure tungsten product (tungstic acid or synthetic scheelite) are indicated below.

Wolframite concentrate: alkaline leaching 370 g/L NaOH, 100º C, particle size <75 µm. four hours, and pulp density 50wt%.

Scheelie concentrate: acidic leaching (400 g/L HCl), 90º C, particle size <20µm, 3-4 hours, and pulp density 3.2 wt%.

Mixed wolframite–scheelite concentrate: (1) alkaline roasting (excess of sodium carbonate, 800º C, two hours; (2) water leaching of the roasted material (90º C, two hours, pulp density: 12.5-16.7 wt%).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.A..; methodology, F.J.A.; investigation, F.J.A. ,M.A., L.J.L., J.I.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.A., M.A., L.J.L., J.I.R.; writing—review and editing, F.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

To the CSIC for support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grohol, M.; Veeh, C. Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU 2023—Final Report; European Commission: Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEss, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huo, G.; Guo, X.; Chen, J. A review of flowsheets for tungsten recovery from scheelite, wolframite and secondary resources and challenges for sustainable production. Hydrometallurgy 2025, 234, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, H.; Peng, Z.; Duan, A.; Zhang, T.; Gong, Z. Leaching of scheelite concentrate for tungsten extraction. Minerals 2025, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chang, J.; Wei, Y.; Qiao, J; Yue, X. ; Fan, H.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X. Green and efficient recovery of tungsten from spent SCR denitration catalyst by Na2S alkali leaching and calcium precipitation. Adv. Sust. Syst. 2025, 9, 2400895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Pu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lei, X.; Hu, H.; Chen, Z. Extraction of tungsten from tungsten fine mud by caustic soda autoclaving. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 6901–6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Yang, Y.; Si, Q.; Liang, C.; Liu, G.; Mi, A.; Wang, S. Recycling efficiency optimization of tungsten-filled vinyl-methyl-silicone-based flexible gamma ray shielding materials. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2025, 57, 103163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Sun, F.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; He, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Z. Synthesis of intermediate valence tungsten oxides via carbon reduction and their dissolution behavior in hydrogen peroxide. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2025, 131, 107191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-Y.; Mu, P.-P.; Liu, H.; Chachina, S.B.; Zhang, X.-G.; Zhang, S.-G.; Pan, D. Extraction and response surface methodology optimization of tungsten and molybdenum from spent fluidized catalytic cracking catalysts. Tungsten, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yi, B.; Hu, X.; Fang, L.; Yu, S.; Yu, S.; Wu, D. Advanced sequential treatment approach for enhanced recovery in tungsten-nickel electroplating wastewater. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2025, 71, 107421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, T.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, H.; Liang, Y. Factors affecting purity of ammonium paratungstate (APT) prepared from wolframite ((Fe,Mn)WO4) concentrate by NaHSO4·H2O roasting, water/ammonia leaching and evaporation crystallization. Hydrometallurgy 2025, 234, 106467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimova, L.; Oleinikova, T.; Terentyeva, I.; Korabayev, A.; Tussupbekova, T. Study of the efficiency of using pelletizing poor scheelite ore for leaching tungsten. Acta Metall. Slovaca 2025, 31, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, I.M.; Yue, H.; Liu, J. An optimisation study for leaching synthetic scheelite in H2SO4 and H2O2 solution. Can. Metall. Q. 2025, 64, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Qiu, Y.; He, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, A.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; He, L.; Sun, F.; Zhao, Z. Research on the ammonia-free solvent extraction of tungsten from sodium tungstate solution using TBP. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J. F-; Alguacil, F.J., Martinez, S., Eds.; Caravaca, C. Produxtion of high-grade tin in a new electrolytic plant. In Hydrometallurgy´94, Institution of Mining and Metal-lurgy, Society of Chemical Industry, Eds. Chapman & Hall: London, United Kingdom, 1994. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Influence of NaOH concentration of tungsten leaching. Temperature: 100º C. Pulp density: 50 wt%. Partucle size: <150 nm.

Figure 1.

Influence of NaOH concentration of tungsten leaching. Temperature: 100º C. Pulp density: 50 wt%. Partucle size: <150 nm.

Figure 2.

Influence of particle size on tungsten leaching. Temperature: 100º C. Pulp densitiy: 50 wt%.

Figure 2.

Influence of particle size on tungsten leaching. Temperature: 100º C. Pulp densitiy: 50 wt%.

Figure 3.

Influence of temperature on tungsten recovery from the scheelite concentrate.

Figure 3.

Influence of temperature on tungsten recovery from the scheelite concentrate.

Figure 4.

Influence of the particle size on tungsten recovery. Temperature: 90º C. HCl concentration: 200 g/L. Pulp density: 3.2 wt%.

Figure 4.

Influence of the particle size on tungsten recovery. Temperature: 90º C. HCl concentration: 200 g/L. Pulp density: 3.2 wt%.

Figure 5.

Influence of the HCl concentration on tungsten recovery. Temperature: 90º C. Pulp density: 3.2 %wt.

Figure 5.

Influence of the HCl concentration on tungsten recovery. Temperature: 90º C. Pulp density: 3.2 %wt.

Figure 6.

SEM image of tungstic acid. Spectrum 2 indicated the presence of oxygen (27.89% weight, 81.63% atomic) and tungsten (72.11% weight, 18.37% atomic). Voltage: 15kV.

Figure 6.

SEM image of tungstic acid. Spectrum 2 indicated the presence of oxygen (27.89% weight, 81.63% atomic) and tungsten (72.11% weight, 18.37% atomic). Voltage: 15kV.

Figure 7.

Removal of tungsten (precipitation of synthetic scheelite) from sodium tungstate solutions at various temperatures.

Figure 7.

Removal of tungsten (precipitation of synthetic scheelite) from sodium tungstate solutions at various temperatures.

Figure 8.

SEM image of the synthetic scheelite. Spectrum 1 indicated the presence of oxygen (28.04% weight, 73.17% atomic), calcium (12.87% weight, 13.41% atomic) and tungsten (59.09% weight, 13.42% atomic). Voltage: 15 kV.

Figure 8.

SEM image of the synthetic scheelite. Spectrum 1 indicated the presence of oxygen (28.04% weight, 73.17% atomic), calcium (12.87% weight, 13.41% atomic) and tungsten (59.09% weight, 13.42% atomic). Voltage: 15 kV.

Figure 9.

XRD spectrum of the synthetic scheelite.

Figure 9.

XRD spectrum of the synthetic scheelite.

Figure 10.

General flow-sheet for the hydrometallurgical treatment of the wolframite concentrate.

Figure 10.

General flow-sheet for the hydrometallurgical treatment of the wolframite concentrate.

Figure 11.

General flow-sheet for hydrometallurgical treatment of the scheelite concentrate.

Figure 11.

General flow-sheet for hydrometallurgical treatment of the scheelite concentrate.

Figure 12.

General flow-sheet for the pyro-hydrometallurgical treatment of the mixed wolframite-scheelite concentrate.

Figure 12.

General flow-sheet for the pyro-hydrometallurgical treatment of the mixed wolframite-scheelite concentrate.

Table 1.

Tungsten content of the three concentrates.

Table 1.

Tungsten content of the three concentrates.

| Concentrate |

% tungsten |

wolframite

scheelite

mixed scheelite-wolframite |

50

23

23 |

Table 2.

Percentages of leaching of tungsten from the mixed concentrate.

Table 2.

Percentages of leaching of tungsten from the mixed concentrate.

| [HCl], M |

Temperature, ºC |

Two hours |

Four hours |

6 M

6 M

6 M

12 M

12 M

12 M |

20

40

80

20

40

80 |

Nil

0.08

0.2

0.04

1

56 |

0.05

0.1

0.3

0.8

1

69 |

Table 3.

Percentage of leaching of tungsten at various pulp densities.

Table 3.

Percentage of leaching of tungsten at various pulp densities.

| Pulp density, wt% |

Two hours |

Four hours |

16.7

8.4

4.2 |

56

21

14 |

69

23

14 |

Table 4.

Influence of the pulp density on tungsten recovery.

Table 4.

Influence of the pulp density on tungsten recovery.

| Time, hours |

16.7 wt% |

8.4 wt% |

4.2 wt% |

2

4

6

8 |

6

9

10

12 |

8

13

16

21 |

10

14

18

21 |

Table 5.

Tests of roasting on the scheelite-wolframite concentrate.

Table 5.

Tests of roasting on the scheelite-wolframite concentrate.

| Test |

Temperature, ºC |

Time, hours |

Excess Na2CO3, % |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14 |

600

600

600

700

700

800

800

800

800

800

800

800

800

800 |

2

1

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

2

2 |

30

40

40

20

30

40

20

20

30

30

40

40

20

40 |

Table 6.

Percentage of tungsten recovery on the roasted materials.

Table 6.

Percentage of tungsten recovery on the roasted materials.

| Test (with respect Table 4) |

Pulp density, wt% |

% W leached |

| 1 |

25

16.7

12.5 |

71

75

80 |

| 5 |

25

16.7

12.5 |

75

80

84 |

| 10 |

25

16.7

12.5 |

80

86

91 |

| 12 |

25

16.7

12.5 |

94

98

99 |

| 14 |

25

16.7

12.5 |

60

69

73 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).