Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

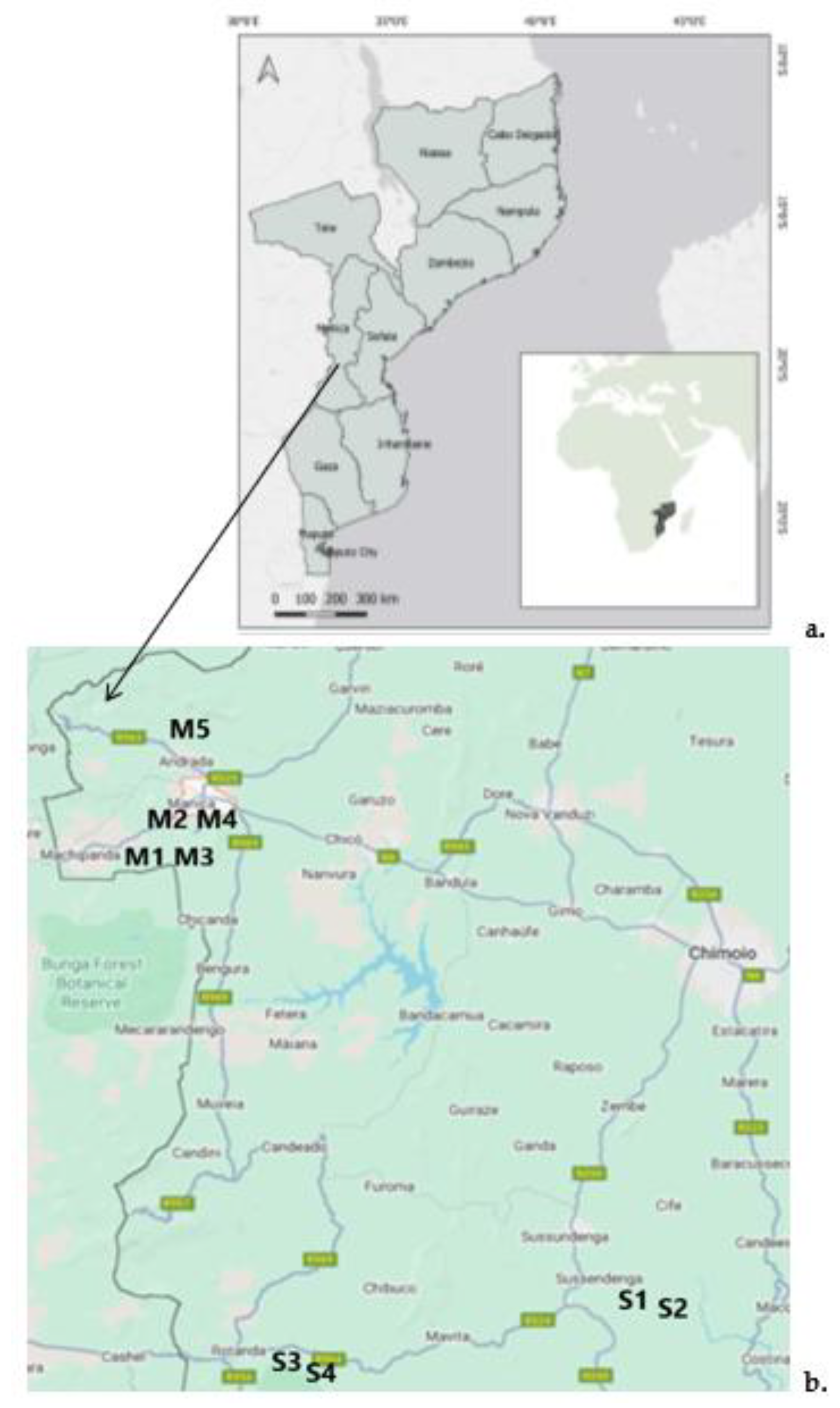

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Soil Sampling

2.3. Preparation and Analysis of the Soils

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

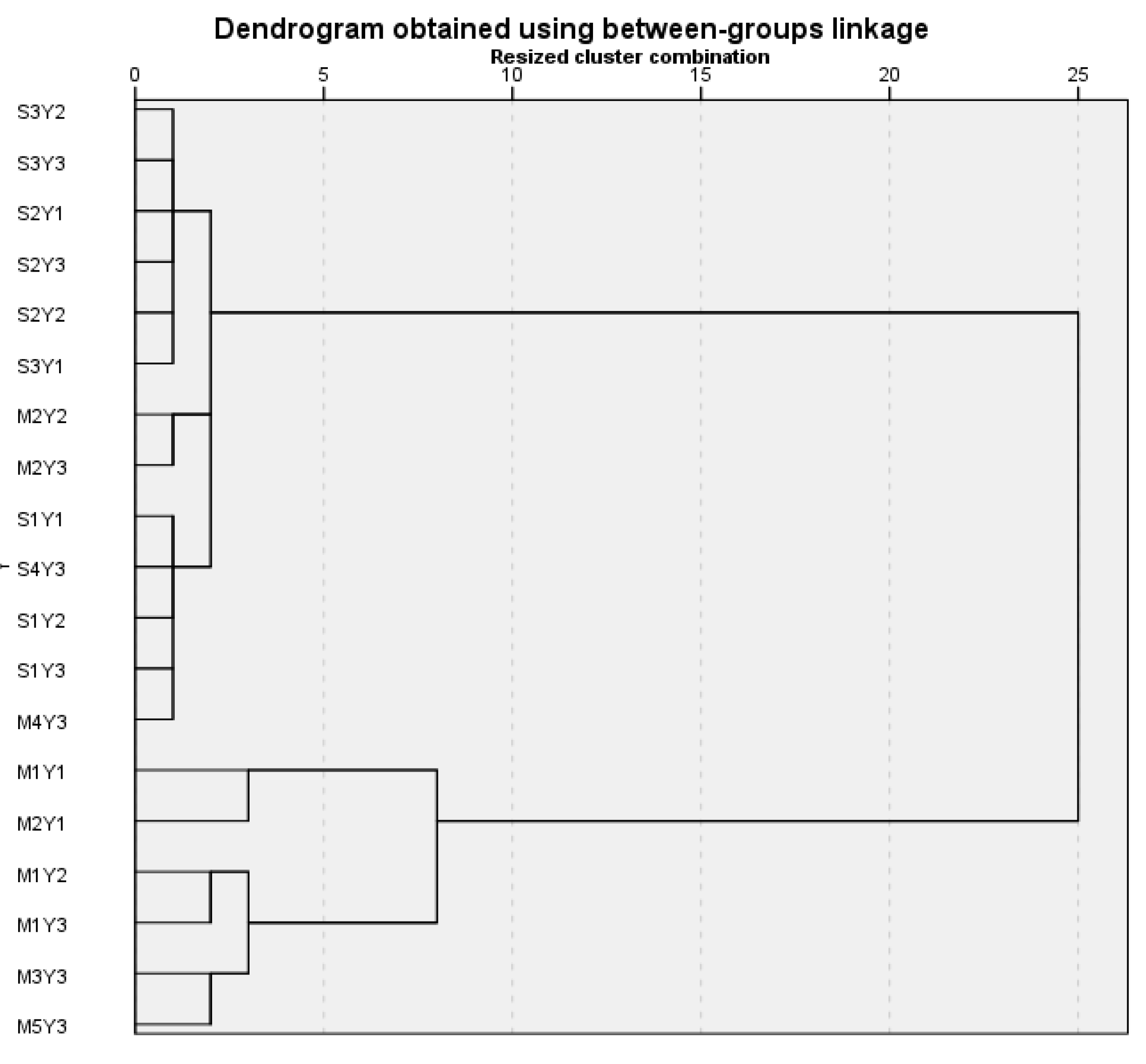

3.1. Agronomical Properties Classification

| Cluster | Samples in the Clusters | Sub-Cluster | Samples in the sub-clusters | Origin of the soils |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A1 | S2Y1. S2Y2. S2Y3. S3Y1. S3Y2. S3Y3 | Sussundenga | ||

| Cluster A2 | M2Y2. M2Y3 M4Y3 S1Y1. S1Y2. S1Y3 S4Y3 |

Cluster A2A | M2Y2. M2Y3 M4Y3 |

Manica |

| Cluster A2B | S1Y1. S1Y2. S1Y3 S4Y3 |

Sussundenga | ||

| Cluster A3 | M1Y1. M2Y1 | Manica | ||

| Cluster A4 | M1Y2. M1Y3 M3Y3 M5Y3 |

Manica |

| Property | Cluster A1 | Cluster A2 | Cluster A3 | Cluster A4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extractable K (K2O). mg/kg | 59 (26) | 155 40) | 204 (45) | 254 (66) |

| Extractable Mg. mg/kg | 52 (13) | 111 (10) | 327 (41) | 586 (3) |

| Extractable Ca. mg/kg | 404 (95) | 565 81) | 1053 (113) | 1462 194) |

| Extractable Fe. mg/kg | 65 (23) | 121 (69) | 206 (11) | 91 (33) |

| Extractable Mn. mg/kg | 31 (17) | 172 (12) | 285 (80) | 409 (31) |

| Extractable Zn. mg/kg | 2.2 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.3) | 2.2 (0) |

| Extractable Cu. mg/kg | 0.45 (0.08) | 2 (1) | 3.6 (0.5) | 5.6 (0.1) |

| Exchangeable Na. cmol(+)/kg | 0.043 (0.008) | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.13 (0.03) | 0.16 (0.04) |

| Exchangeable K. cmol(+)/kg | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.04) | 0.38 (0) | 0.50 (0.08) |

| Exchangeable Ca. cmol(+)/kg | 2.0 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.4) | 5.2 (0.6) | 7.3 (0.9) |

| Exchangeable Mg. cmol(+)/kg | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.90 (0.07) | 2.8 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.8) |

| CEC. cmol(+)/kg | 2.7 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.4) | 8.5 (0.9) | 13 (2) |

| pH(KCl) 1:5 | 4.9 (0.3) | 5.0 (0.3) | 5.3 (0.1) | 5.3 (0.1) |

| pH(H2O) 1:5 | 5.6 (0.3) | 5.9 (0.3) | 6.0 (0) | 6.4 (0.1) |

| Extractable P (P2O5). mg/kg | 41 (7) | 89 (87) | 119 (24) | 48 (18) |

| Organic Carbon (%) | 0.68 (0.07) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.9 (01) |

| Organic Matter (%) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.2) |

| Nitrogen Kjeldahl. g/kg | 0.8 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.2) | 1.10(0.03) | 13.0 (0.2) |

| Nitrate (N-NO3). mg/kg | 12 (7) | 7 (4) | 21 (12) | 9 (3) |

| Conductivity. mS/m | 5.7 (0.9) | 6 (2) | 11 (1) | 6 (1) |

| Sand (%) | 79 (4) | 69 (2) | 59 (4) | 27 (5) |

| Clay (%) | 11 (1) | 16 (2) | 24 (1) | 38 (3) |

| Silt(%) | 10 (4) | 15 (2) | 17 (5) | 35 (2) |

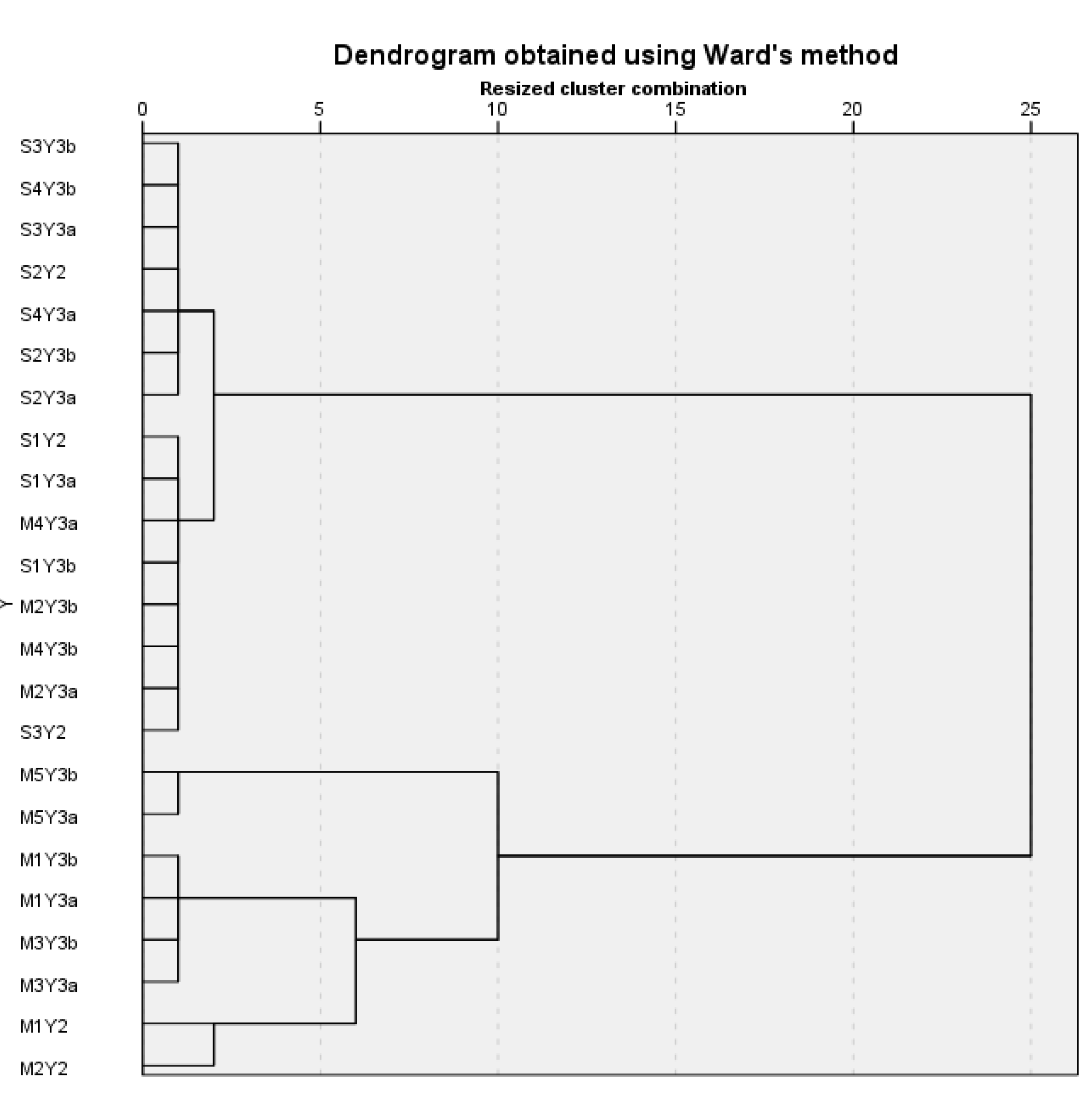

3.2. Metal Polutants Soil Classification

| Cluster | Samples in the Clusters | Origin of the soils |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster H1 | S2Y2, S2Y3b, S2Y3a S3Y3b, S3Y3a, S4Y3b S4Y3a |

Sussundenga |

| Cluster H2 | M2Y3b, M2Y3a M4Y3b, M4Y3a S1Y2, S1Y3b, S1Y3a S3Y2 |

Manica / Sussundenga |

| Cluster H3 | M5Y3b, M5Y3a | Manica |

| Cluster H4 | M1Y3b, M1Y3a M3Y3b, M3Y3a |

Manica |

| Cluster H5 | M1Y2, M2Y2 | Manica |

| Cluster H1 | Cluster H2 | Cluster H3 | Cluster H4 | Cluster H5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba | 18 (3) | 33 (12) | 110 (14) | 63 (2) | 50 (24) |

| Cr | 4 (4) | 102 (95) | 315 (7) | 1700 (355) | 840 (791) |

| Co | 1 (1) | 11 (7) | 59 (4) | 101 (13) | 48 (44) |

| Cu | 1 (2) | 9 (5) | 115 (7) | 34 (4) | 22 (13) |

| Pb | 4 (1) | 8 (4) | 18 (1) | 9 (1) | 76 (16) |

| Ni | 1 (2) | 34 (32) | 120 (14) | 715 (84) | 379 (425) |

| V | 5 (3) | 27 (10) | 280 (0) | 96 (16) | 61 (35) |

| Zn | 0 | 13 (2) | 53 (11) | 30 (2) | 24 (9) |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrett, C.; Bevis, L. The self-reinforcing feedback between low soil fertility and chronic poverty. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Bevis, L. Soil Fertility and Poverty in Developing Countries. Choices 2019. 34. Quarter 2. Available online: http://www.choicesmagazine.org/choices-magazine/theme-articles/soil-health-policy-in-the-united-states-and-abroad/soil-fertility-and-poverty-in-developing-countries.

- Government of Mozambique. Voluntary National Review of Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development; Government of Mozambique: Maputo, Mozambique, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marassiro. M.J.; Romarco de Oliveira. M.L.; Pereira, G.P. Family farming in Mozambique: Characteristics and challenges. Research. Society and Development 2021, 10, e22110615682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Jones, A.; Lugato, E.; Ballabio, C. A Soil Monitoring Law for Europe. Global Challenges 2025, 9, 2400336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chianu, J.N.; Chianu, J.N.; Mairura, F. Mineral fertilizers in the farming systems of sub-Saharan Africa. A review. Environmental and Resource Economics 2019, 74, 1239–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, R.M.; Yost, R. A Survey of Soil Fertility Status of Four Agroecological Zones of Mozambique. Soil Science 2006, 171, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichongue, O.; van Tol, J.; Ceronio, G.; Preez, C.D. Effects of Tillage Systems and Cropping Patterns on Soil Physical Properties in Mozambique. Agriculture 2020, 10, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrani. D.; Cocco, S.; Cardelli, V.; D’Ottavio, P.; Rafael, R.B.A.; Feniasse, D.; Vilanculos, A.; Fernández-Marcos, M.L.; Giosué, C.; Tittarelli, F.; Corti, G. Soil fertility in slash and burn agricultural systems in central Mozambique. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 322, 116031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, E.C.R.; Geurts. P.M.H.; Francisco, J.R. Assessment of soil fertility depletion in Mozambique. Agriculture. Ecosystems and Environment 1998, 71, 159–167. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.J.S.L.; Esteves da Silva, J. Assessment of the Quality of Agricultural Soils in Manica Province (Mozambique). Environments 2024, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonella, P.; Gillerb, K.E. When yield gaps are poverty traps: The paradigm of ecological intensification in African smallholder agriculture. Field Crops Research 2013, 143, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Kelly, V.A.; Kopicki, R.J.; Byerlee, D. Fertilizer use in African agriculture: Lessons learned and good practice guidelines. The World Bank. 2007. Available: https://documents.worldbank.org/pt/publication/documents-reports/ documentdetail/498591468204546593/fertilizer-use-in-african-agriculture-lessons-learned-and-good-practice-guidelines. (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Denning, G.; Kabambe, P.; Sanchez, P.; Malik, A.; Flor, R.; Harawa, R.; Nkhoma, P.; Zamba, C.; Banda, C.; Magombo, C.; Keating, M.; Wangila, J.; Sachs, J. Input Subsidies to Improve Smallholder Maize Productivity in Malawi: Toward an African Green Revolution. PLoS Biology 2009, 7, e1000023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, P.A.; Swaminathan, M.S. Hunger in Africa: the link between unhealthy people and unhealthy soils. Lancet 2005, 365, 442–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevis, L.; Kim, K.; Guerena, D. Soil zinc deficiency and child stunting: Evidence from Nepal. Journal of Health Economics 2023, 87, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.M.; Pullabhotla, H.; Bevis, L.; Lobell, D.B. Soil micronutrients linked to human health in India. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.K.; Muruganandam. M.; Ali, S.S.; Kornaros, M. Clean-Up of Heavy Metals from Contaminated Soil by Phytoremediation: A Multidisciplinary and Eco-Friendly Approach. Toxics 2023, 11, 422. [CrossRef]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A Review of Sources. Chemistry. Risks and Best Available Strategies for Remediation. ISRN Ecology 2011, 402647. [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Shentu, J.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Baligar, V.C.; He, Z. Sources. Indicators and Assessment of Soil Contamination by Potentially Toxic Metals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, Y.; Lan, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, X.; Du, L. Comprehensive assessment of harmful heavy metals in contaminated soil in order to score pollution level page range. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A.; Deyholos, M.K.; Sanogo, S.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Beck, L. Heavy Metal Contamination in Agricultural Soil: Environmental Pollutants Affecting Crop Health. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Chakraborty, J.C.; Tareq, A.M.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Khusro, A.; Idris, A.M.; Khandaker, M.U.; Osman, H.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Impact of heavy metals on the environment and human health: Novel therapeutic insights to counter the toxicity. Journal of King Saud University – Science 2022, 34, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanga, S.; Suna, L.; Suna, Y.; Songa, K.; Qina, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Xue, Y. Towards an integrated health risk assessment framework of soil heavy metals pollution: Theoretical basis, conceptual model, and perspectives. Environmental Pollution 2013, 316, 120596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Kim, J.E.; Islam, A.; Bilal, M.; Rakib, R.; Nandi, R.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, T. Heavy metals contamination and associated health risks in food webs—a review focuses on food safety and environmental sustainability in Bangladesh. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 3230–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.J.S.L.; Esteves da Silva, J. Environmental Stressors of Mozambique Soil Quality. Environments 2024, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, F. Soil health cluster analysis based on national monitoring of soil indicators. European Journal of Soil Science 2021, 72, 2414–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, R.; Burrough, P.A. Multiple discriminant analysis in soil survey. European Journal of Soil Science 1974, 25, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerkasem, B.; Jamjod, S.; Pusadee, T. Productivity limiting impacts of boron deficiency, a review. Plant Soil 2020, 455, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contaminated Soils - Technical Guide. REFERENCE VALUES. To the ground. Amadora. January 2019. (Review 3 - September 2022). Portuguese Environment Agency (APA). Solos Contaminados – Guia Técnico. VALORES DE REFERÊNCIA. PARA O SOLO. AMADORA. JANEIRO DE 2019. (REVISÃO 3 – SETEMBRO DE 2022). Agencia Portuguesa do Ambiente (APA).

- Raso, E.F.; Savaio, S.S.; Mulima, E.P. Impact of artisanal gold mining on agricultural soils: Case of the district of Manica. Mozambique. Revista Verde 2022, 17, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, A.; Winkler, M.S.; Cambaco, O.; Cossa, H.; Kihwele, F.; Lyatuu, I.; Zabre, H.R.; Farnham, A.; Macete, E.; Munguambe, K. S.; Cambaco, O.; Cossa, H.; Kihwele, F.; Lyatuu, I.; Zabre, H.R.; Farnham, A.; Macete, E.; Munguambe, K. Health impacts of industrial mining on surrounding communities: Local perspectives from three sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondeyne, S.; Ndunguru, E.; Rafael, P.; Bannerman, J. Artisanal mining in central Mozambique: Policy and environmental issues of concern. Resources Policy 2009, 34, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, K.; Marzi, M.; Rezaei, H. Heavy metal concentration in the agricultural soils under the different climatic regions: a case study of Iran. Environmental Earth Sciences 2020, 79, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daulta, R.; Prakash, M.; Goyal, S. Metal content in soils of Northern India and crop response: a review. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 20, 4521–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Feng, D.; Su, X. Heavy metal contamination in Shanghai agricultural soil. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).