Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How does the relationship between educational attainment and employment outcomes vary across fields of study, institution types, and demographic groups?

- What specific educational experiences and institutional practices most strongly predict positive employment outcomes, controlling for pre-existing student characteristics?

- How do key stakeholders—employers, educators, and recent graduates—perceive the changing relationship between higher education and employment success?

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

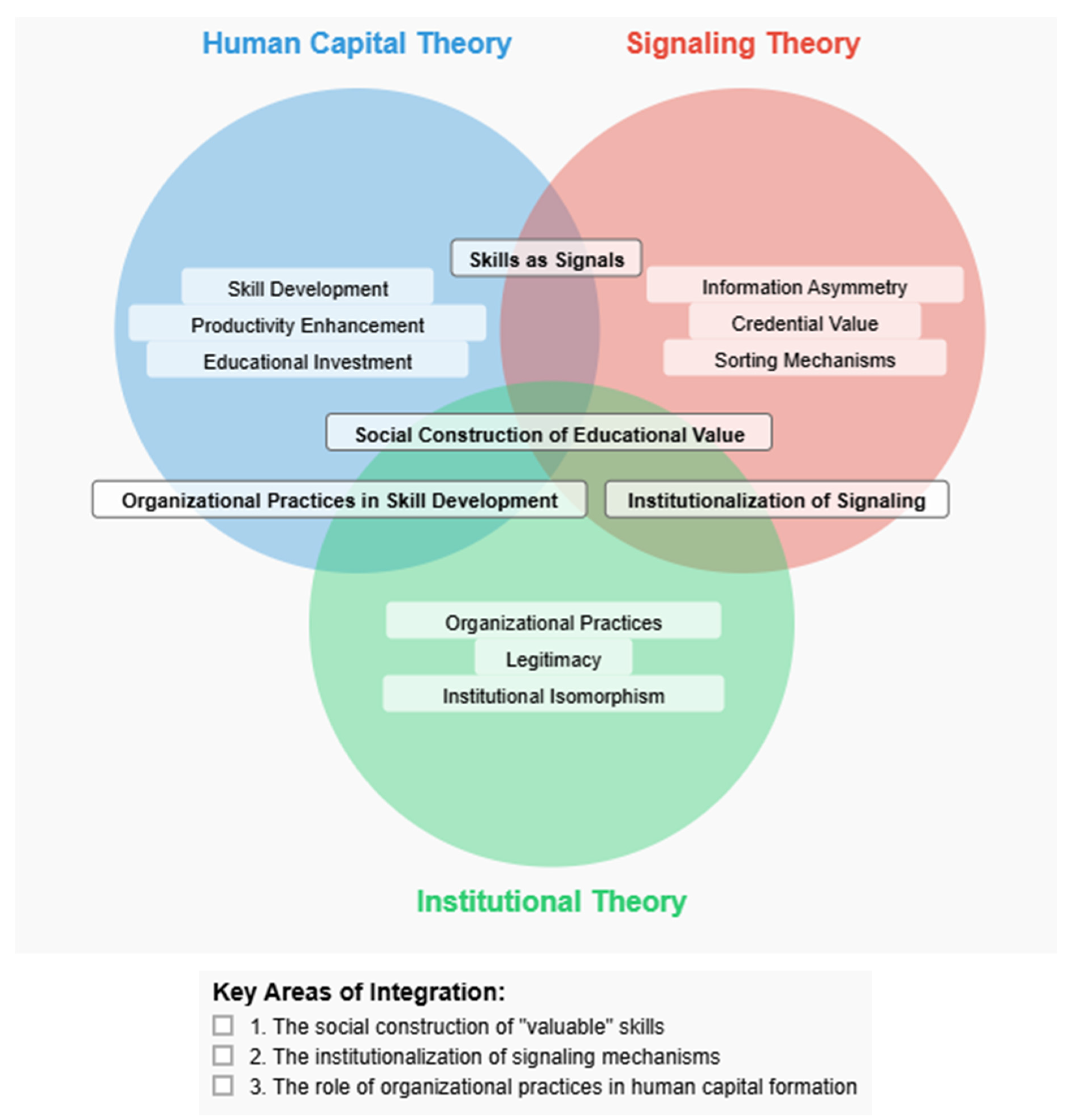

2.1. Integrated Theoretical Perspectives

2.2. Human Capital Theory

2.3. Signaling Theory

2.4. Institutional Theory

2.5. Social Reproduction and Inequality Perspectives

2.6. International Comparative Context

3. Methods

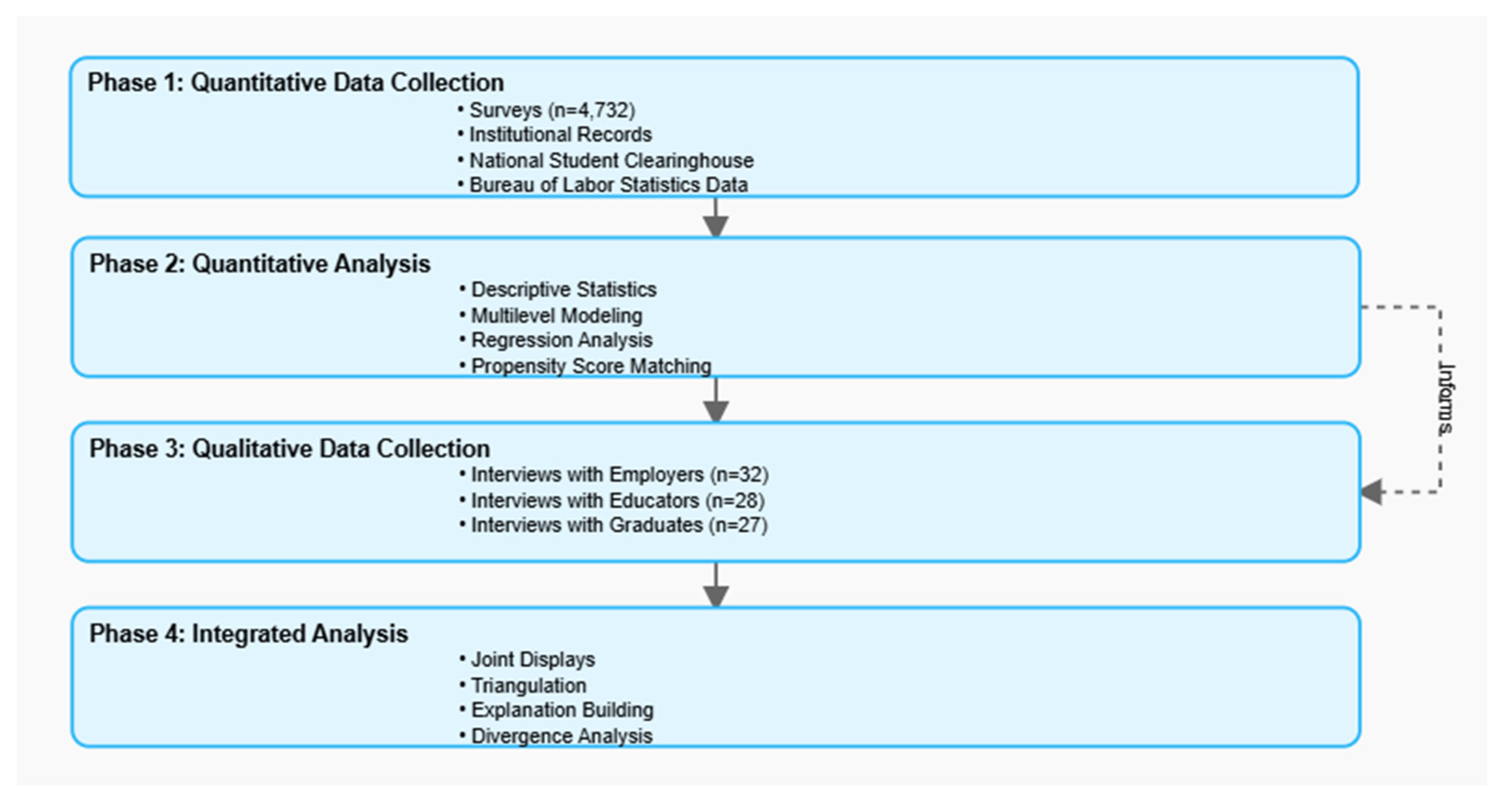

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

3.2.1. Sample and Data Sources

- Institutional student records (demographic characteristics, academic performance, program participation)

- National Center for Education Statistics

- National Student Clearinghouse data (educational trajectories)

- Graduate surveys administered at graduation and annually for five years post-graduation (n=4,732 at baseline, with response rates of 78%, 65%, 61%, 58%, and 55% in subsequent years)

- Bureau of Labor Statistics and Census Bureau data for regional economic indicators

3.2.2. Measures

- Employment status at 6, 12, and 60 months post-graduation

- Annual salary at 6, 12, and 60 months post-graduation (adjusted for regional cost of living using BEA Regional Price Parities)

- Job satisfaction (5-point Likert scale, α = .89)

- Job-education alignment (5-point scale measuring perceived relevance of education to current role, α = .86)

- Career progression (composite measure of promotion, responsibility increases, and skill utilization, α = .83)

- Institutional characteristics (Carnegie classification, selectivity [using Barron's competitiveness ratings], size, funding model)

- Program of study (coded using CIP classification system)

- Academic performance metrics (GPA, honors designation)

- High-impact educational experiences (internships, research experiences, study abroad, etc.)

- Demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, first-generation status, socioeconomic indicators)

- Pre-college characteristics (high school GPA, standardized test scores, extracurricular involvement)

3.2.3. Analytical Approach

3.3. Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

3.3.1. Sample and Recruitment

- Employers (n=32) representing diverse industries, organization sizes, and geographic regions

- Higher education administrators and faculty (n=28) from varied institution types

- Recent graduates (n=27) selected to represent diverse educational pathways and employment outcomes

3.3.2. Interview Protocol

3.3.3. Analytical Approach

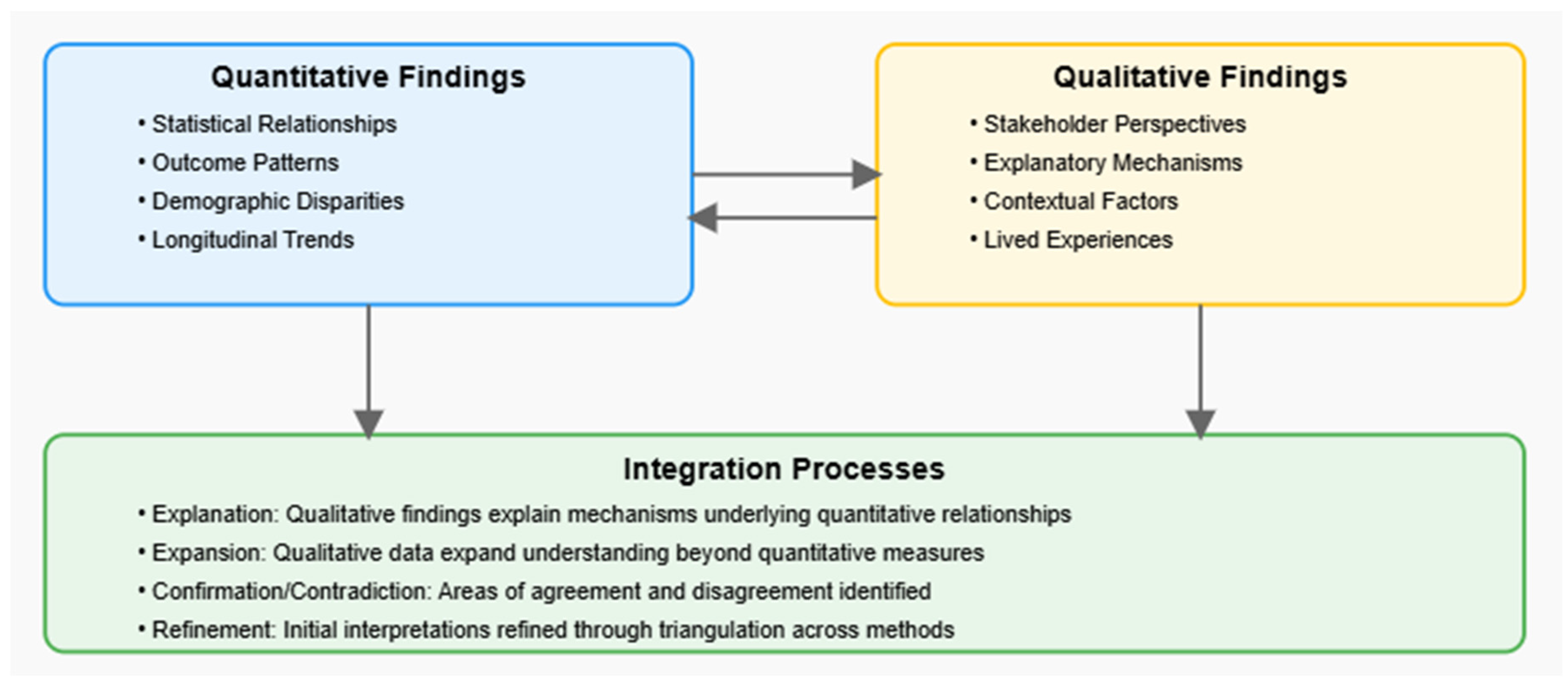

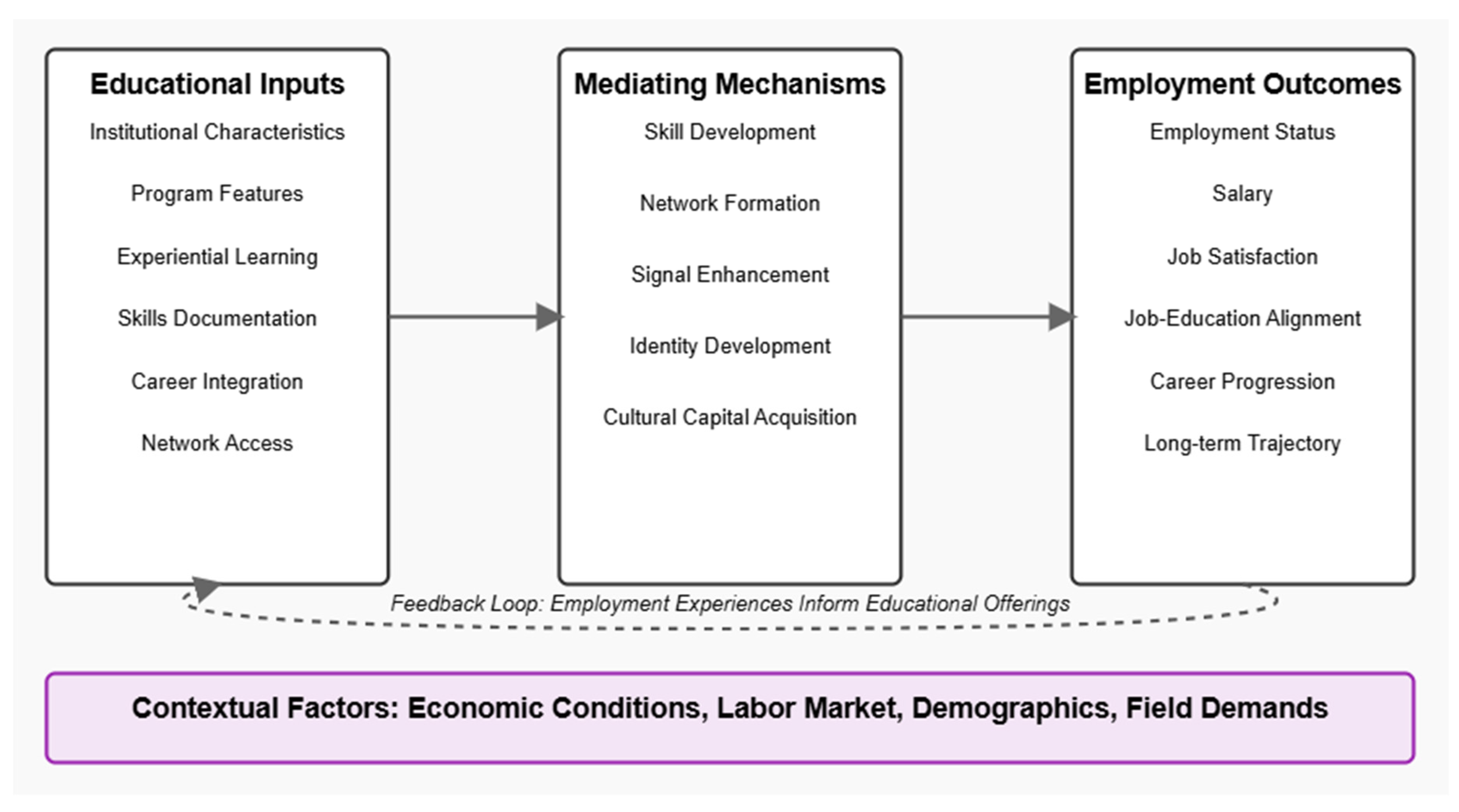

3.4. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

- Explanation - Qualitative findings were used to explain mechanisms underlying quantitative relationships

- Expansion - Qualitative data expanded understanding beyond what quantitative measures captured

- Confirmation/Contradiction - Areas of agreement and disagreement between datasets were identified

- Refinement - Initial interpretations were refined through triangulation across methods

- The quantitative data suggested stronger and more consistent effects of high-quality internships than qualitative accounts, which revealed more variability in how these experiences translate to outcomes. This divergence prompted deeper analysis of contextual factors that might moderate internship effectiveness.

- Qualitative data revealed greater concerns about the narrowing of educational purpose than would be predicted based on the quantitative emphasis on employment outcomes alone. This highlighted the importance of examining outcomes beyond employment metrics.

- Institutional prestige showed smaller direct effects in recent quantitative data than many qualitative accounts suggested, indicating potential misalignment between perceptions and measurable impacts. This divergence prompted examination of how institutional reputation might operate through mechanisms not captured in quantitative measures.

3.5. Reflexivity and Researcher Positionality

3.6. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Findings

4.1.1. Education-Employment Relationship Across Groups

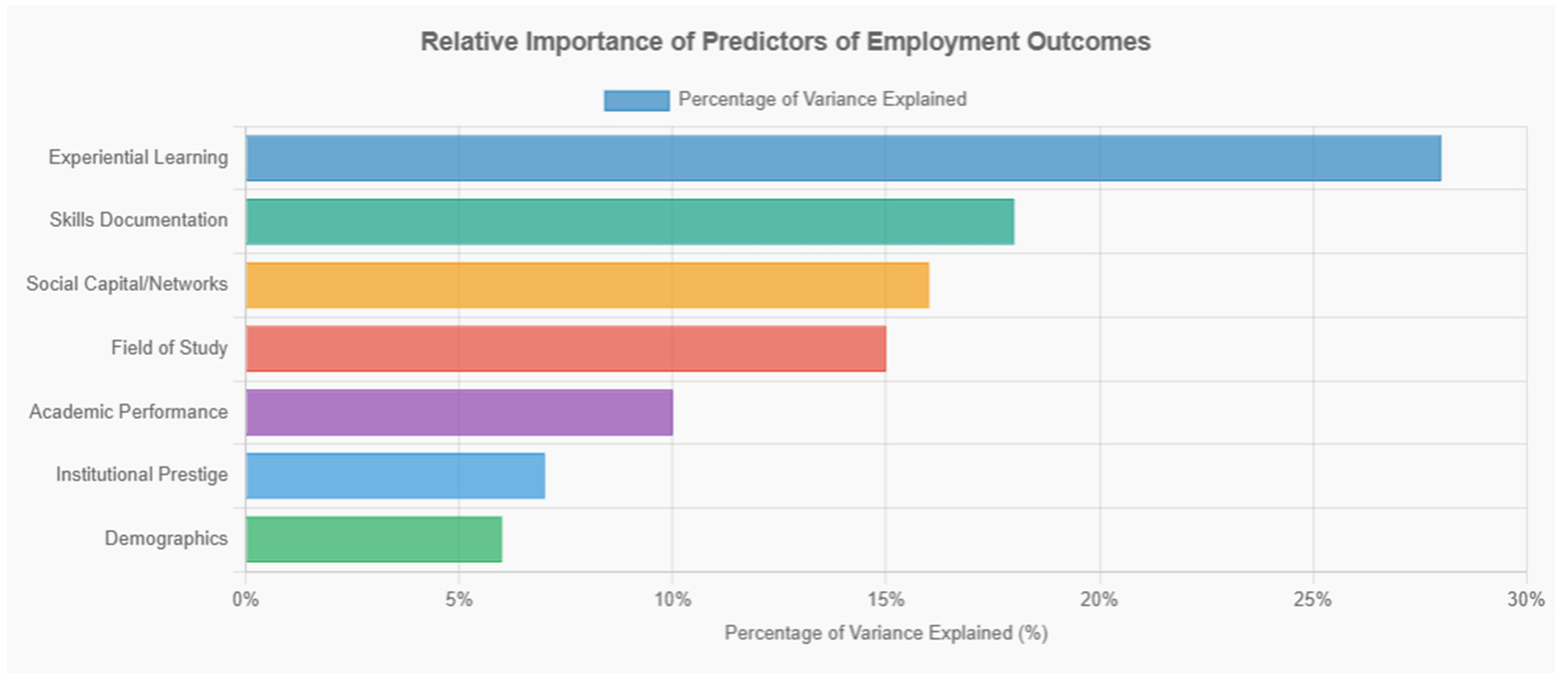

4.1.2. Predictors of Employment Success

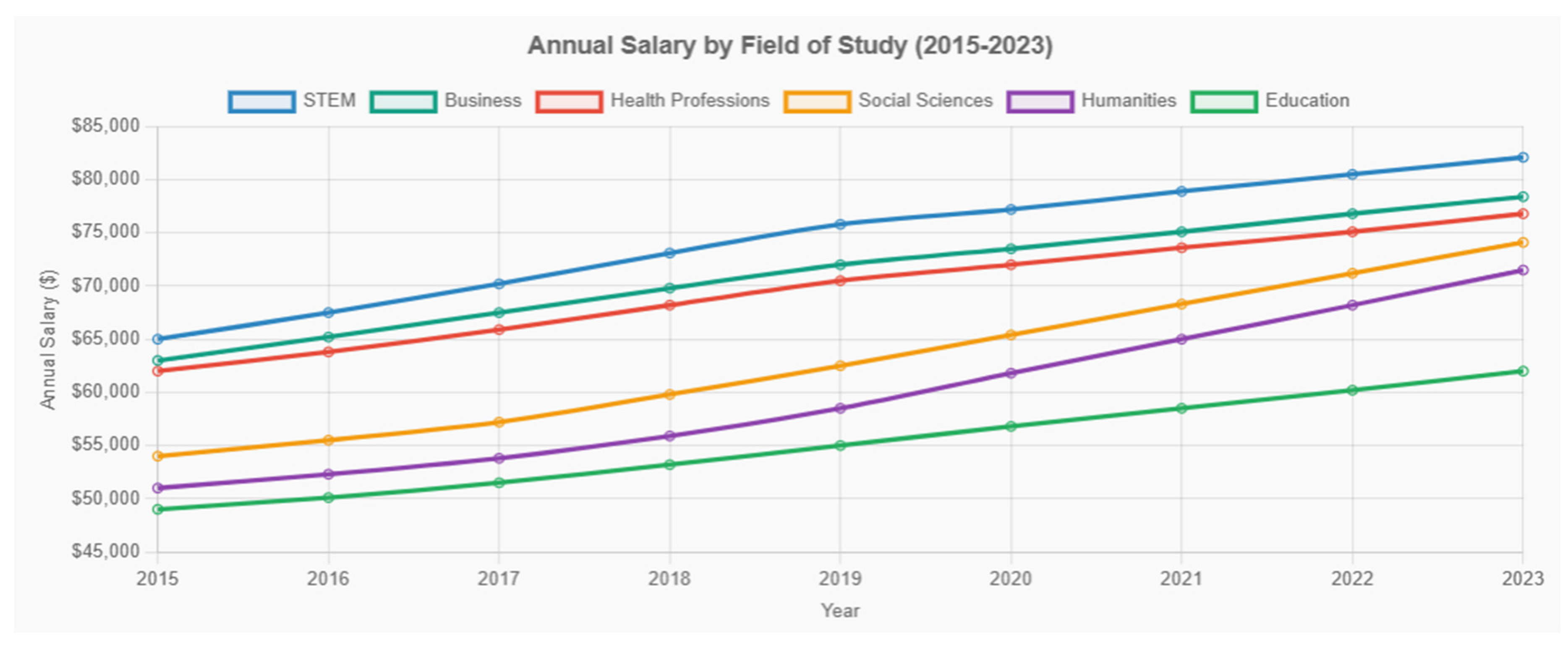

4.1.3. Longitudinal Patterns

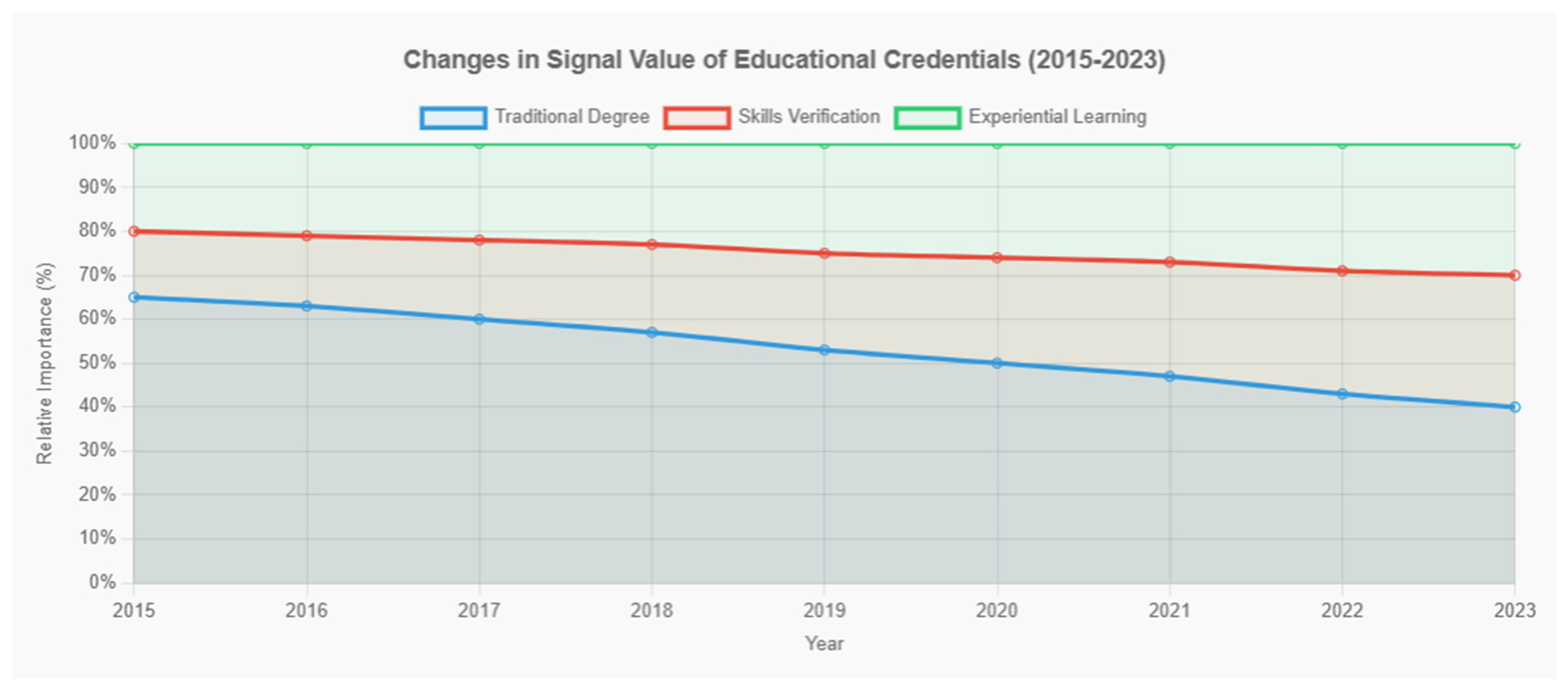

- Rising Importance of Skills Verification: The explanatory power of skills-based credentials increased significantly over the study period, with the regression coefficient for skills documentation rising from β=0.12 in 2015 to β=0.31 in 2023 (p<.001 for trend, 95% CI [0.14, 0.23]).

- Declining Premium for Institutional Prestige: The direct effect of institutional selectivity on employment outcomes decreased from explaining 23% of variance in 2015 to 14% in 2023 (p<.01 for trend, 95% CI [5%, 13%]), while the mediating effect of experiential learning opportunities increased.

- Increasing Field Convergence: Wage differentials between fields narrowed over time, with the gap between highest and lowest-paying fields decreasing by 18% over the study period (p<.05, 95% CI [8%, 28%]). This convergence was particularly notable in later career stages (years 3-5), suggesting that initial field-based advantages may diminish as careers progress.

- COVID-19 Effects: The COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021) temporarily disrupted these longitudinal trends, with institutional prestige regaining importance during peak uncertainty. However, by 2022-2023, pre-pandemic trends had largely resumed, with skills verification and experiential learning showing increased importance relative to traditional credentials.

- Economic Context Effects: Sensitivity analyses examining the influence of macroeconomic conditions showed that the relative importance of different predictors varied with labor market tightness. During periods of higher unemployment (2020-2021), institutional prestige and field of study explained more variance, while during tighter labor markets (2022-2023), specific skills and experiences became relatively more important.

4.2. Qualitative Findings

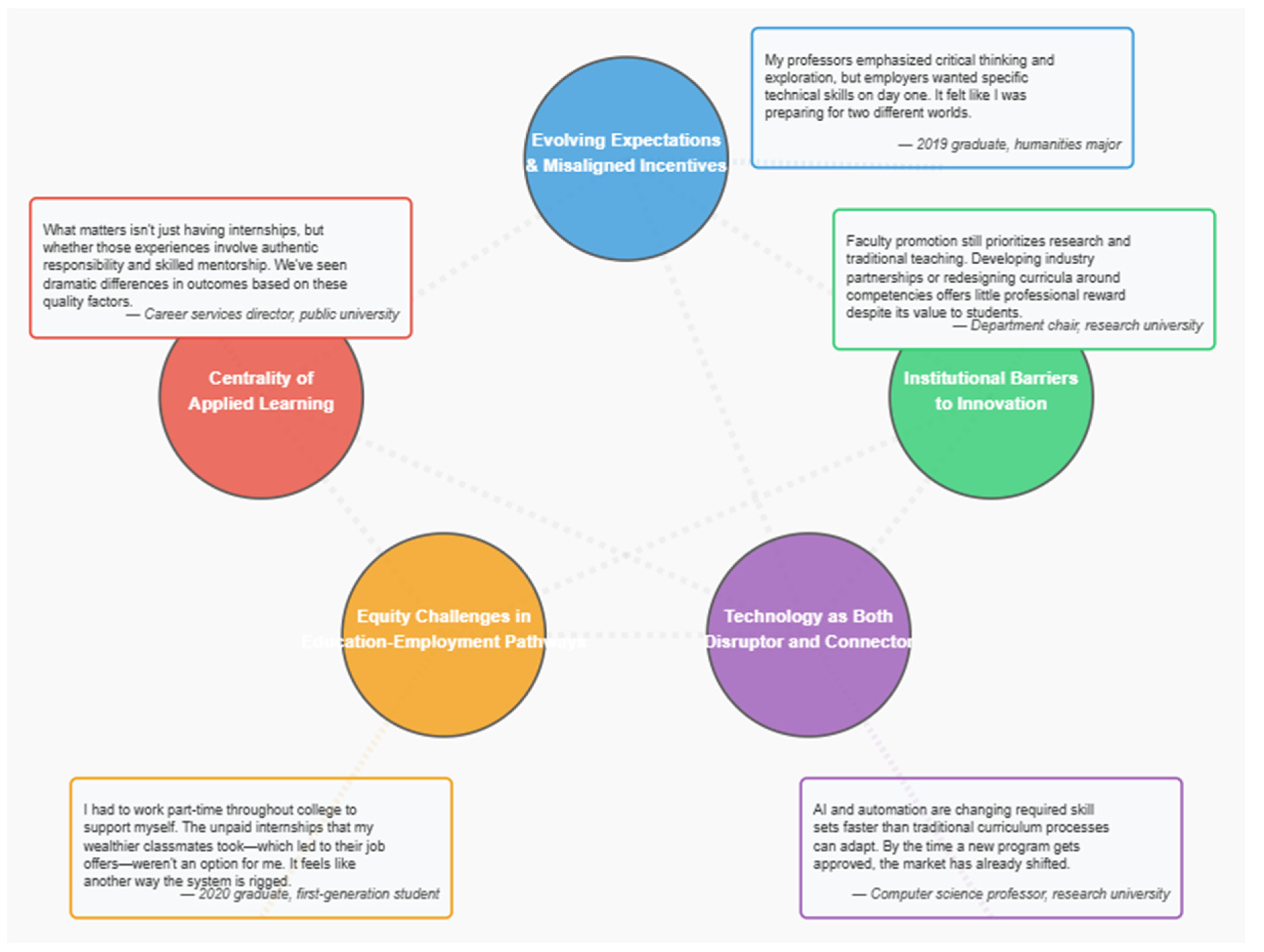

4.2.1. Evolving Expectations and Misaligned Incentives

"We're less concerned with where someone went to school and more focused on what they can actually do. The credential gets them in the door, but their portfolio and demonstrated capabilities get them the job." (Manufacturing employer, mid-sized company)

"We're looking for people who can adapt, communicate effectively, and solve complex problems. The specific technical skills they bring are less important than these fundamental capabilities, especially since our technical needs change constantly." (Consulting firm partner, large company)

"There's a fundamental tension between education as preparation for citizenship and critical thinking versus education as job training. The pressure to focus exclusively on employment outcomes risks undermining our broader educational purpose." (Dean, liberal arts college)

"When we reduce education to job preparation, we're shortchanging students. The most valuable aspects of education are often those that don't translate directly to specific jobs—the capacity for critical inquiry, ethical reasoning, and engagement with diverse perspectives." (Philosophy professor, public university)

"The push to align education with employer needs often masks questions about whose needs are being served and whose are being marginalized. We need to prepare students not just to fit into existing systems but to transform them when necessary." (Sociology professor, liberal arts college)

"My professors emphasized critical thinking and exploration, but employers wanted specific technical skills on day one. It felt like I was preparing for two different worlds." (2019 graduate, humanities major)

"I value the broader education I received, but I also needed to find a job. The challenge was figuring out how to translate what I learned into terms employers would recognize and value." (2017 graduate, social sciences major)

"Our institution's rhetoric emphasizes career readiness, but faculty are rewarded primarily for research and traditional teaching. There's little incentive to develop the kinds of experiential learning that actually prepare students for employment." (Department chair, public university)

"Our executives talk about investing in talent development, but managers are evaluated on quarterly metrics that discourage longer-term investments in education partnerships." (Human resources director, healthcare organization)

4.2.2. The Centrality of Applied Learning

"What matters isn't just having internships, but whether those experiences involve authentic responsibility and skilled mentorship. We've seen dramatic differences in outcomes based on these quality factors." (Career services director, public university)

"Technical skills are necessary but insufficient. What separates successful early-career professionals is understanding organizational contexts—how to navigate structures, communicate effectively, and apply knowledge in ambiguous situations. You can't learn that from coursework alone." (Technology employer, large company)

"When students apply concepts in authentic contexts, they develop deeper understanding of the theoretical material. It's not about replacing academic learning with practical training, but about strengthening both through integration." (Engineering professor, research university)

"My internship was when I started seeing myself as a professional rather than just a student. That shift in identity was almost more important than the specific skills I developed." (2018 graduate, business major)

"Our wealthier students can afford to take unpaid internships in expensive cities, building connections with prestigious employers. First-generation and lower-income students often can't access these opportunities without substantial institutional support, which is rarely adequate." (Career counselor, private university)

"I had to work part-time throughout college to support myself. The unpaid internships that my wealthier classmates took—which led to their job offers—weren't an option for me. It feels like another way the system is rigged." (2020 graduate, first-generation student)

"Our industry has always operated this way. Students get valuable experience and connections, and we get enthusiastic help. It's a win-win." (Media executive, small company)

"We've created a stipend program that provides funding for low-income students to take unpaid internships. We also work with employers to convert unpaid positions to paid ones, explaining how this broadens their talent pool and improves diversity." (Career center director, public university)

4.2.3. Institutional Barriers to Innovation

"Faculty promotion still prioritizes research and traditional teaching. Developing industry partnerships or redesigning curricula around competencies offers little professional reward despite its value to students." (Department chair, research university)

"There's a cultural hierarchy that values theoretical work over applied work, traditional disciplines over interdisciplinary efforts, and individual scholarship over collaborative projects with external partners. These values are baked into our evaluation systems." (Provost, comprehensive university)

"Career services operates separately from academic departments, student affairs is separate from both, and alumni relations is yet another silo. Each has different reporting lines, different metrics, different cultures. Coordinating across these boundaries is exhausting." (Career education director, private university)

"We want to partner more deeply with educational institutions, but our quarterly performance metrics don't reward long-term talent development investments. The people who control budgets often don't understand the strategic value." (HR director, healthcare organization)

"Large corporations have dedicated university relations teams and recruitment budgets. As a small business, we can't compete for attention from educational institutions. The systems are designed for big players." (Owner, small manufacturing company)

"There's a fundamental mismatch between academic and business timeframes. Curriculum changes take years; business needs change quarterly. Neither side fully appreciates the constraints the other operates under." (Business school dean, public university)

"Competency-based approaches make sense for connecting education and employment, but accreditation still primarily focuses on credit hours and seat time. Innovating within these constraints requires tremendous effort." (Academic affairs administrator, community college)

"Progress happens when you find champions on both sides who understand both worlds and can translate between them. It's relationship-driven work that happens despite systems, not because of them." (Industry partnership director, research university)

"We built this amazing partnership program, but when the dean who championed it left, support eroded. Without structural changes to incentive systems, innovations remain vulnerable to leadership changes." (Faculty member, comprehensive university)

4.2.4. Equity Challenges in Education-Employment Pathways

"My degree opened some doors, but I didn't have the family connections or understanding of unwritten professional rules that many of my peers did. The transition was much harder than I expected." (2017 graduate, first-generation student)

"I didn't know how to network, how to negotiate salary, when to speak up in meetings—all these unwritten rules that my peers from professional families seemed to know instinctively." (2020 graduate, first-generation student)

"We recognize that traditional hiring practices disadvantage candidates without established networks. We've redesigned our process to focus on skills demonstration rather than referrals or pedigree, and it's significantly improved diversity outcomes." (Financial services employer, large company)

"We just hire the best candidates regardless of background. If certain groups aren't making it through our process, it must be because they don't have the qualifications we need." (Engineering firm manager, mid-sized company)

"There's a difference between offering the same opportunities to everyone and ensuring everyone can access and benefit from those opportunities. We're still struggling to move from the former to the latter." (Diversity officer, public university)

"Many of our support programs focus on 'fixing' students from marginalized backgrounds rather than fixing the institutional structures that create barriers in the first place." (Student success director, comprehensive university)

"I was well-prepared academically, but navigating gendered expectations in male-dominated workplaces wasn't something my education addressed. I've had to learn how to be assertive without being labeled 'difficult' or 'aggressive.'" (2018 graduate, engineering major)

"As a Black woman in finance, I'm navigating both racial and gender biases simultaneously. My education prepared me for the technical aspects of the work but not for these identity-related challenges." (2019 graduate, business major)

"Our professional identity program works explicitly with underrepresented students on navigating workplace cultures while maintaining authenticity. We pair this with employer education to address biased practices rather than placing all the adaptation burden on students." (Career equity director, private university)

4.2.5. Technology as Both Disruptor and Connector

"AI and automation are changing required skill sets faster than traditional curriculum processes can adapt. By the time a new program gets approved, the market has already shifted." (Computer science professor, research university)

"The half-life of technical skills is shortening, while the importance of adaptability, critical thinking, and learning capacity is increasing. This shift requires rethinking the balance between specific and transferable skills in education." (Technology employer, large company)

"Digital credentials that verify specific competencies rather than just completion have been transformative for our hiring. They provide granular information about capabilities that traditional transcripts never could." (Technology employer, mid-sized company)

"Learning analytics tools help us identify skill development patterns and connect them to employment outcomes. This feedback loop allows us to refine curricula more responsively." (Institutional research director, public university)

"The line between education and work is blurring. We're seeing more continuous learning models where people move between educational experiences and work throughout their careers, rather than completing education first and then working." (Continuing education director, community college)

"The rush toward digital credentials and online learning risks creating new forms of exclusion. Students without reliable technology access or digital literacy skills are being left behind in these 'innovative' approaches." (Educational technology researcher, private university)

"Algorithmic hiring tools promise to reduce bias, but they often encode existing patterns of advantage into seemingly objective systems. We need to approach these technologies critically." (Diversity and inclusion officer, technology company)

"The pandemic forced rapid adoption of remote learning and virtual recruitment. Some changes were long overdue, but we're still grappling with which elements should remain permanent and which created new problems." (University administrator, public university)

"When everything went remote, we saw immediately how unequal technology access was among our students. Some were trying to complete coursework on smartphones with limited data plans while others had high-speed connections and multiple devices." (Faculty member, comprehensive university)

"We're moving toward more fluid, technology-enabled learning and working arrangements that will require different support structures and policies. The traditional boundaries between education and employment will continue to blur." (Future of work researcher, research university)

4.3. Integrated Findings

4.3.1. Complementary Evidence on Experiential Learning

- Tacit Knowledge Development: Internships provide context-specific knowledge that cannot be fully developed in classroom settings:"You can teach technical skills in a classroom, but understanding how to apply them in specific organizational contexts requires immersion in those environments." (Engineering employer, large company)

- Professional Identity Formation: Experiential learning helps students develop professional self-concepts:"When students successfully complete authentic work in professional settings, they begin to see themselves differently—as contributors rather than just learners. This identity shift is transformative." (Psychology professor, liberal arts college)

- Network Development: High-quality experiences create valuable professional connections:"The technical skills I gained in my internship were important, but the relationships I built have been even more valuable for my career progression." (2018 graduate, business major)

- Signal Clarification: These experiences provide clearer signals to employers than academic records alone:"When I see a candidate who's completed a substantive internship in our industry, it reduces uncertainty about their capabilities and fit. It's a much stronger signal than grades or coursework." (Healthcare administrator, mid-sized organization)

4.3.2. Explanatory Mechanisms for Demographic Disparities

- Differential Access to High-Value Experiences: Financial constraints limit access to unpaid or low-paid internships that often serve as gateways to prestigious employers:"I couldn't afford to take the unpaid internships in New York that led to jobs at top firms. Those opportunities were effectively reserved for students who could afford to work for free." (2019 graduate, first-generation student)

- Unequal Social Capital: Different access to professional networks affects both opportunity awareness and entry pathways:"Many of our job openings are filled through employee referrals before they're even publicly posted. This benefits candidates with connections to current employees, who tend to come from similar backgrounds." (HR manager, professional services firm)

- Cultural Capital Disparities: Unwritten expectations about professional behavior advantage students already familiar with workplace norms:"I didn't know how to 'read the room' in professional settings or when to speak up versus when to listen. These subtle cultural skills weren't taught in my classes but seemed to be assumed knowledge." (2020 graduate, first-generation student)

- Bias in Evaluation: Subjective assessments of "fit" and potential often disadvantage candidates from underrepresented groups:"Even with similar qualifications, candidates from underrepresented groups are often perceived as 'riskier' hires or less likely to 'fit' with existing team dynamics." (Diversity officer, financial services firm)

4.3.3. Understanding Institutional Change Resistance

- Misaligned Incentive Systems: Faculty reward structures prioritize research and traditional teaching over practices that enhance employment outcomes:"Promotion decisions rarely consider industry partnerships or experiential learning development, so faculty rationally focus their energy elsewhere." (Associate dean, research university)

- Organizational Silos: Fragmented structures separate functions that need to work together:"Academic departments, career services, alumni relations, and employer relations all operate separately, making coordinated approaches nearly impossible." (Career services director, comprehensive university)

- Competing Conceptions of Purpose: Fundamental disagreements about educational goals create resistance:"Many faculty see employment preparation as diluting our core academic mission rather than as an integrated aspect of student development." (Humanities department chair, liberal arts college)

- Resource Constraints: High-impact practices often require greater resources:"We know high-quality internships make a difference, but supervising them properly requires faculty time that isn't accounted for in workload models." (Experiential learning coordinator, public university)

- Developing hybrid roles that bridge academic and career functions

- Creating alternative reward structures that recognize employment-connected work

- Framing changes in terms of enhancing rather than replacing academic values

- Building external partnerships that provide additional resources

4.3.4. Clarifying Skills Verification Effects

- Shifting from Proxy Measures to Direct Assessment: Employers are moving away from using credentials as proxies for capabilities:"We've realized that the university someone attended or even their major doesn't tell us enough about what they can actually do. We need more direct evidence of capabilities." (Technology employer, large company)

- Addressing Information Asymmetry: Skills documentation reduces uncertainty in hiring decisions:"Detailed information about specific competencies reduces the risk in hiring decisions. It gives us more confidence that a candidate can perform effectively." (Healthcare employer, mid-sized organization)

- Responding to Credential Inflation: As degree attainment has increased, employers seek additional differentiation:"When everyone has a degree, it no longer serves as an effective sorting mechanism. We need additional signals to distinguish between qualified candidates." (HR director, professional services firm)

- Adapting to Accelerating Skill Changes: Rapid technological change requires more granular understanding of capabilities:"Job requirements are changing so quickly that broad credentials aren't sufficient. We need to understand specific skill sets that may cut across traditional disciplines." (Manufacturing employer, large company)

- Concerns about reducing education to discrete skills at the expense of broader capabilities

- Questions about who defines valuable skills and how these definitions may reflect existing power structures

- Potential for new forms of exclusion based on access to skills documentation opportunities

- Challenges in verifying more complex capabilities like critical thinking and collaboration

4.3.5. Contextualizing Field Convergence

- Increasing Value of Transferable Skills: As technological change accelerates, adaptability and broader capabilities become more valuable:"Technical skills have a shorter half-life than they used to. What increasingly distinguishes successful professionals is their ability to learn, adapt, and integrate knowledge across domains." (Technology executive, large company)

- Growing Importance of Communication and Social Skills: These capabilities, often developed in humanities and social sciences, have increasing value:"As routine technical work becomes automated, the distinctively human capabilities—communication, empathy, ethical reasoning—become more central to professional success." (Professional services employer, large company)

- Career Evolution Over Time: Technical advantages may be more valuable early in careers, while leadership and integrative capabilities become more important later:"Technical skills get you in the door, but advancement increasingly depends on broader capabilities like strategic thinking, team leadership, and complex problem-solving." (Senior manager, healthcare organization)

- Increasing Interdisciplinarity in Professional Contexts: Work increasingly requires integration across traditional disciplinary boundaries:"The most interesting problems exist at the intersections of fields. People who can connect different domains of knowledge are increasingly valuable." (Research director, technology company)

"As we better understand the complexity of real-world problems, we're recognizing that solutions require multiple forms of knowledge—technical, social, ethical, cultural. This shifts how we value different educational backgrounds." (Executive director, nonprofit organization)

4.3.6. Areas of Methodological Divergence

-

Internship Impact Variability: The quantitative data suggested stronger and more consistent effects of high-quality internships than qualitative accounts, which revealed more variability in how these experiences translate to outcomes. While regression analyses showed relatively uniform benefits across contexts, qualitative interviews revealed substantial variation in how internship experiences affected different individuals:"My internship was transformative—it completely changed my career trajectory and opened doors I didn't know existed." (2019 graduate, business major)"My internship checked a box on my resume, but it didn't really change how I thought about my career or give me valuable connections." (2018 graduate, humanities major)This divergence suggests that averages captured in quantitative analyses may mask important individual variation in how experiences translate to outcomes.

-

Educational Purpose Concerns: Qualitative data revealed greater concerns about the narrowing of educational purpose than would be predicted based on the quantitative emphasis on employment outcomes alone. While quantitative measures focused primarily on employment metrics, qualitative interviews revealed rich discussion of education's broader purposes:"I worry that our focus on employability metrics is crowding out attention to intellectual curiosity, civic engagement, and personal transformation—aspects of education that may not show up in employment data but are fundamentally important." (Liberal arts professor, private college)This divergence highlights the limitations of quantitative metrics in capturing the full range of educational values and outcomes.

- Prestige Perception Gap: Institutional prestige showed smaller direct effects in recent quantitative data than many qualitative accounts suggested, indicating potential misalignment between perceptions and measurable impacts. While regression analyses showed declining direct effects of institutional selectivity, many participants continued to describe prestige as highly influential:"The name of your school still opens or closes doors, regardless of what you actually learned there." (2020 graduate, public university)

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.1.1. Reconceptualizing Human Capital Development

5.1.2. Evolving Signaling Mechanisms

5.1.3. Institutional Adaptation and Resistance

5.1.4. Social Reproduction and Inequality Dynamics

5.1.5. Theoretical Integration

5.2. Practical Implications

5.2.1. For Educational Institutions

- Prioritize Quality in Experiential Learning: Rather than simply increasing the quantity of internships or other experiential opportunities, institutions should focus on quality factors that predict positive outcomes. This includes ensuring authentic responsibility, skilled supervision, connection to academic learning, and substantive skill development. Creating frameworks for assessing and improving experiential learning quality is more valuable than merely tracking participation rates.

- Develop Equitable Access to High-Impact Experiences: Institutions should implement targeted strategies to ensure that first-generation, low-income, and underrepresented minority students can access career-enhancing experiences. This includes creating paid internship funds, developing employer partnerships focused on equity, embedding professional development within required coursework rather than as optional add-ons, and providing structured support for navigating professional environments.

- Integrate Career Development Throughout the Curriculum: Rather than treating career preparation as separate from academic learning, institutions should integrate career-relevant experiences and reflection throughout the curriculum. This integration strengthens both academic learning and employment preparation while ensuring all students access these benefits regardless of whether they opt into separate career services.

- Implement Transparent Skills Documentation: Institutions should develop systematic approaches to documenting the specific skills and competencies students develop, making the outcomes of education more transparent to both students and employers. This documentation should include both technical and transferable skills, with verification of capability rather than merely course completion.

- Address Institutional Barriers: Addressing structural barriers to innovation requires examining faculty reward systems, organizational silos, and resource allocation models. Institutions should develop recognition systems that value education-employment connections, create cross-functional roles that bridge traditional boundaries, and allocate resources to support high-impact practices.

- Maintain Educational Breadth: While strengthening employment connections, institutions should maintain commitment to broader educational purposes including critical thinking, civic engagement, ethical reasoning, and personal development. These purposes are not opposed to employment preparation but are increasingly valued in work contexts as well as in broader life domains.

5.2.2. For Employers

- Move Beyond Credential-Based Filtering: Employers should reduce reliance on institutional prestige and other proxy measures in initial candidate screening, instead developing more direct assessments of relevant capabilities. This approach not only improves prediction of performance but also increases diversity by considering candidates from a broader range of educational backgrounds.

- Develop More Inclusive Early-Career Pathways: Creating more structured onboarding and development for recent graduates can reduce barriers for those without inherited professional knowledge. This includes explicit communication of expectations, mentoring programs, and developmental feedback approaches that recognize learning curves for early-career professionals.

- Create High-Quality Experiential Opportunities: Employers should design internships and other experiential opportunities that provide authentic responsibility, skilled supervision, and substantive learning. Paying for these experiences not only addresses equity concerns but also expands the talent pool and improves program quality.

- Engage More Deeply in Educational Partnerships: Rather than approaching educational institutions merely as talent sources, employers should develop deeper partnerships that include curriculum input, faculty engagement, and collaborative learning experiences. These partnerships create mutual value and strengthen alignment between educational experiences and workplace needs.

- Examine Selection and Advancement Practices for Bias: Employers should regularly audit recruitment, hiring, and promotion practices for potential biases that disadvantage graduates from certain backgrounds or institutions. This includes examining where position announcements are shared, what selection criteria are prioritized, how "fit" is assessed, and what factors influence advancement decisions.

5.2.3. For Policymakers

- Develop Funding Mechanisms for Equitable Experiential Learning: Public funding for paid internships, cooperative education, and other applied learning experiences can reduce financial barriers that currently limit access. These investments should target institutions serving underrepresented populations and fields where unpaid experiences are common.

- Create Skills Transparency Frameworks: Policy frameworks for documenting and verifying skills across educational providers can increase transparency while maintaining quality standards. These frameworks should balance standardization for clarity with flexibility for innovation and context-specific needs.

- Align Accreditation with Evidence-Based Practices: Accreditation requirements should encourage high-impact educational practices while allowing flexibility in implementation. This includes recognizing alternative approaches to credit hour requirements when competency development can be verified.

- Support Cross-Sector Partnerships: Public funding for education-industry partnerships can strengthen connections while ensuring these relationships serve public purposes rather than narrow interests. These partnerships are particularly important for small employers and institutions with limited resources for partnership development.

- Develop Comprehensive Data Systems: Longitudinal data connecting educational experiences with employment outcomes (while protecting privacy) can inform both policy and practice. These systems should track equity dimensions to identify and address disparities in how educational experiences translate to employment outcomes.

5.2.4. For Students and Families

- Seek Programs with Integrated Career Development: Students should look for educational programs that integrate career development throughout the curriculum rather than treating it as an add-on service. This integration provides more comprehensive preparation while ensuring all students benefit regardless of help-seeking behaviors.

- Prioritize High-Quality Experiential Learning: When evaluating educational options, students should consider access to high-quality experiential learning opportunities, including how these experiences are structured, supervised, and connected to academic learning.

- Develop Professional Networks Intentionally: Students should recognize the importance of building professional connections during their education and seek opportunities to develop these networks, particularly if they don't have existing family connections in their field of interest.

- Focus on Skill Development and Documentation: Students should be intentional about developing and documenting specific skills and competencies, seeking opportunities to demonstrate capabilities beyond course completion.

- Consider Long-Term Trajectories, Not Just Initial Outcomes: When making educational choices, students should consider long-term career trajectories rather than focusing exclusively on starting salaries. Different educational paths may have different earnings trajectories over time, with some fields showing steeper growth after initial entry.

5.3. Addressing Structural Inequities

5.3.1. Institutional Level

- Financial Support for Experiential Learning: Institutions should create dedicated funding for low-income students to participate in unpaid or low-paid internships, research, and other experiences that build social capital and professional skills. These funds should cover not just stipends but also related costs like transportation, professional attire, and housing in high-opportunity locations.

- Cultural Capital Development: Programs should explicitly address the unwritten rules and expectations of professional environments that advantage students from privileged backgrounds. This includes intentional development of professional communication, workplace norms understanding, and navigation of implicit expectations.

- Social Capital Formation: Institutions should create structured opportunities for students from backgrounds with less inherited professional networks to develop connections with alumni, employers, and other professional contacts. These might include mentoring programs, networking events designed with first-generation students in mind, and alumni connection platforms.

- Identity-Conscious Support: Support programs should address the specific challenges faced by students with marginalized identities, including preparation for navigating biased environments without placing the full burden of adaptation on these students. This includes both individual preparation and institutional advocacy for more inclusive workplace practices.

- Structural Analysis in Career Education: Career education should incorporate critical analysis of structural barriers and systemic inequities rather than focusing exclusively on individual strategies. This helps students contextualize their experiences within broader patterns and develop more effective navigation approaches.

5.3.2. Employer Level

- Inclusive Recruitment Approaches: Employers should expand recruitment beyond traditional feeder institutions to include regional and minority-serving institutions. This includes developing sustained relationships with diverse institutions rather than occasional outreach.

- Paid Internship Commitments: Converting unpaid to paid internships not only addresses financial barriers but often improves program quality by increasing accountability for providing substantive experiences. Industry coalitions can establish standards for paid experiences to prevent competitive disadvantages for early adopters.

- Skills-Based Assessment: Developing more structured, skills-based assessment approaches in hiring can reduce reliance on signals that correlate with socioeconomic advantage. This includes work sample tests, structured behavioral interviews, and assessment of demonstrated capabilities rather than prestige markers.

- Early-Career Support: Recognizing that early-career professionals from underrepresented backgrounds may have had less exposure to professional norms, employers should develop structured support systems including clear expectations, mentoring, and developmental feedback.

- Advancement Pathway Transparency: Making advancement criteria explicit rather than implicit helps employees from all backgrounds understand how to progress. Regular equity audits of promotion patterns can identify whether advancement systems are producing equitable outcomes.

5.3.3. Policy Level

- Policy interventions should address structural barriers to equitable outcomes:

- Federal Work-Study Reform: Reforming federal work-study to prioritize career-relevant placements and expand off-campus opportunities would provide more equitable access to professional experience during college.

- Tax Incentives for Inclusive Hiring: Tax incentives for employers who develop substantive partnerships with minority-serving and regional institutions could expand opportunity pipelines beyond elite institutions.

- Wage Standards for Internships: Establishing minimum wage requirements for internships would reduce economic barriers while improving program quality through increased accountability.

- Data Reporting Requirements: Requiring institutions to report on participation in high-impact practices by demographic group would increase transparency and create accountability for equitable access.

- Portable Benefits for Early-Career Workers: Developing portable benefit systems for early-career workers in freelance, contract, or internship roles would reduce risks associated with non-traditional entry paths that are increasingly common in many fields.

5.3.4. Individual Level

- Strategic Experience Selection: Students from underrepresented backgrounds should prioritize educational experiences that build both human capital and social capital, recognizing that both are necessary for translating educational achievements into employment opportunities.

- Explicit Cultural Knowledge Seeking: Intentionally seeking information about unwritten professional expectations can help bridge gaps in inherited cultural capital. This includes finding mentors who can explain implicit norms and expectations.

- Network Development Focus: Recognizing the crucial role of professional networks, students without inherited connections should strategically allocate time and energy to building relationships with potential career contacts, including faculty, alumni, and professionals in fields of interest.

- Self-Advocacy Skills: Developing skills for effective self-advocacy, including articulating the value of one's experiences and negotiating for opportunities and compensation, is particularly important for students from backgrounds that may not have provided models for these behaviors.

5.4. Balancing Employment Preparation and Broader Educational Purposes

- Problem-Based Learning: Approaches that engage students with authentic, complex problems can simultaneously develop technical skills, critical thinking capabilities, and contextual understanding. These approaches are particularly effective when problems address meaningful social challenges rather than artificial scenarios.

- Community-Engaged Learning: Experiences that connect academic learning with community needs can develop both civic commitments and practical capabilities. These experiences help students see connections between their field and broader social contexts while developing implementation skills.

- Reflective Practice Frameworks: Structured reflection that connects theory and practice helps students develop metacognitive capabilities valuable in both professional and civic contexts. These frameworks encourage students to examine assumptions, consider multiple perspectives, and develop contextual awareness.

- Integrative Learning Portfolios: Documentation approaches that prompt students to connect learning across contexts and demonstrate both specific skills and broader capabilities can bridge employment preparation and wider educational purposes. These portfolios can serve both developmental and showcase functions.

- Ethical Reasoning Integration: Incorporating ethical reasoning throughout professional preparation helps students develop capabilities for addressing value conflicts and considering implications beyond technical dimensions. This integration is increasingly important as technological change creates new ethical challenges across fields.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

- Extended Longitudinal Tracking: Studies following graduates over 10+ years would provide insight into how the education-employment relationship evolves across career stages. This extended timeframe is particularly important for understanding fields where initial earnings may not reflect long-term trajectories.

- Comparative International Research: Cross-national studies could illuminate how different educational systems and labor market structures shape these relationships, identifying alternative models and their outcomes. Particular attention to countries with different approaches to education-employment connections (e.g., German dual education, Nordic models) could provide valuable comparative insights.

- Intervention Studies: Experimental or quasi-experimental studies testing specific approaches to strengthening education-employment connections would build on our correlational findings to establish causal relationships. These might include randomized controlled trials of specific interventions or natural experiments leveraging policy changes that affect some but not all students.

- Mixed-Methods Institutional Ethnographies: In-depth studies of specific institutional contexts could provide richer understanding of how organizational practices and cultures shape education-employment pathways. These studies could examine how institutional logics, power dynamics, and organizational structures influence both innovation and resistance to change.

- Alternative Outcome Measures: Research incorporating broader measures of post-graduation success—including well-being, civic engagement, and personal development—would provide a more holistic understanding of educational value. This approach aligns with capabilities perspectives that consider functioning across multiple life domains rather than focusing solely on economic outcomes.

- Technology Impact Studies: Research specifically examining how emerging technologies (AI, automation, digital credentials) are reshaping both educational delivery and employment assessment would provide insight into rapidly evolving dimensions of the education-employment relationship. This includes attention to both opportunities and risks associated with technological change.

- Equity-Focused Implementation Research: Studies examining specific approaches to reducing demographic disparities in education-employment pathways would provide practical guidance for institutional change. This research should include attention to implementation challenges and contextual factors that influence intervention effectiveness.

6. Conclusion

Appendix A: Graduate Employment Outcomes and Educational Experiences Survey

- Name: _______________________

- Email: _______________________

- Phone: _______________________

- Year of graduation: _____________

- Degree earned: ________________

- Major/field of study: ____________

- Age at graduation: _____________

- Gender:

- 9.

- Race/Ethnicity (select all that apply):

- 10.

- Are you the first in your family to graduate from college?

- 11.

- What was the highest level of education completed by either of your parents/guardians?

- 12.

- What was your approximate family income during your college years?

- 13.

- High school GPA (on a 4.0 scale): _____________

- 14.

- Did you take any standardized college entrance exams?

- 15.

- If yes, please provide your highest scores:

- 16.

- Please rate your level of involvement in high school extracurricular activities:

- 17.

- Cumulative college GPA (on a 4.0 scale): _____________

- 18.

- Did you graduate with any academic honors or distinctions?

- 19.

- During your undergraduate education, did you participate in any of the following? (Select all that apply)

- 20.

- If you completed an internship or co-op, please answer the following:

- 21.

- For your most significant internship/co-op experience, please rate the following on a scale of 1-5 (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree):

- 22.

- Did your program include explicit documentation of skills or competencies (e.g., skills transcript, portfolio, competency-based assessment)?

- 23.

- How would you rate the integration of career preparation in your academic program?

- 24.

- How would you rate your access to professional networks during your education?

- 25.

- Did you use career services at your institution?

- 26.

- How would you rate the quality of career services at your institution? (1-5 scale): _____

- 27.

- Did you have any significant mentors during your education?

- 28.

- What is your current employment status?

- 29.

- If employed, please provide the following information:

- 30.

- How long did it take you to secure your first position after graduation?

- 31.

- Is your current position related to your field of study?

- 32.

- On a scale of 1-5 (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely), how would you rate:

- 33.

- Since graduation, have you:

- 34.

- In your current or most recent job, how often do you use the knowledge and skills acquired during your education?

- 35.

- Which aspects of your education have been most valuable in your career? (Select up to 3)

- 36.

- Which aspects of your education have been least relevant to your career? (Select up to 3)

- 37.

- What educational experiences do you wish you had pursued that might have better prepared you for your career? (Select all that apply)

- 38.

- How has your perception of the value of your education changed since graduation?

- 39.

- On a scale of 1-5 (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely), how would you rate the return on investment of your education? _____

- 40.

- Have you pursued additional formal education since graduation?

- 41.

- If yes, what type of education? (Select all that apply)

- 42.

- Have you participated in employer-provided training or professional development?

- 43.

- How important is continuing education/lifelong learning in your career field?

- 44.

- What aspects of your educational experience best prepared you for your current career?

- 45.

- What gaps do you perceive between your educational preparation and workplace demands?

- 46.

- How do you believe higher education could better align with employment needs?

- 47.

- What advice would you give to current students in your field to better prepare for employment?

- 48.

- Is there anything else you would like to share about your education-to-employment transition?

- 49.

- May we contact you for follow-up research?

- 50.

- Would you be interested in participating in an in-depth interview about your education-to-employment experiences?

Appendix B: Interview Protocols

- Could you tell me about your educational background, including your degree, field of study, and when you graduated?

- What were your career expectations while you were in college? How did these evolve during your education?

- What motivated your choice of institution and field of study?

- 4.

- Walk me through your transition from education to employment. What was that experience like for you?

- 5.

- What challenges did you face in this transition? What factors facilitated a smoother transition?

- 6.

- How long did it take you to find employment related to your field of study? What was that search process like?

- 7.

- In what ways did your educational institution support your transition to employment? Where do you feel that support was lacking?

- 8.

- Looking back, which specific educational experiences do you believe have been most valuable in your career? Why?

- 9.

- Tell me about any internships, co-ops, or experiential learning opportunities you participated in. How did these experiences influence your career path?

- 10.

- How well do you feel your academic program prepared you for the technical aspects of your work? For the social and organizational aspects?

- 11.

- Were there any particular courses, projects, or activities that proved especially relevant to your current work? Can you provide specific examples?

- 12.

- Were there skills or knowledge areas that you needed in the workplace that were not adequately addressed in your education? Please elaborate.

- 13.

- How has your understanding of what skills and competencies are most valuable in your field changed since graduation?

- 14.

- In what ways did your education help you develop and document specific skills or competencies? How have employers responded to these credentials?

- 15.

- Beyond technical skills, what other capabilities (e.g., communication, teamwork, problem-solving) have been important in your professional development? How were these fostered during your education?

- 16.

- How did your educational experiences help you develop professional networks? How important have these connections been in your career?

- 17.

- If you're a first-generation college student or from an underrepresented group, how has this affected your ability to leverage your education for career advancement?

- 18.

- What role have mentors played in your educational and professional development? How did these mentoring relationships form?

- 19.

- How would you characterize the culture of your educational institution regarding career preparation? Was career development integrated throughout your program or treated as separate?

- 20.

- How did the reputation or brand of your institution affect your employment opportunities? Can you provide specific examples?

- 21.

- How responsive was your program to changing industry needs or practices? Did you perceive any tensions between academic traditions and workplace demands?

- 22.

- How has technology affected the relationship between your education and career development?

- 23.

- In what ways has your field changed since you completed your education? How has this affected the relevance of your educational preparation?

- 24.

- Have you pursued additional education or credentials since graduation? What motivated these decisions?

- 25.

- If you could redesign your educational experience knowing what you know now, what would you change?

- 26.

- What advice would you give to educational institutions seeking to better prepare graduates for employment success?

- 27.

- What recommendations would you give to employers about better recognizing and utilizing the capabilities of recent graduates?

- 28.

- How do you see the relationship between education and employment evolving in the future? What implications might this have for students, institutions, and employers?

- 29.

- Is there anything else about your education-to-employment journey that you'd like to share that we haven't covered?

- 30.

- Do you have any questions for me about this research?

- Could you tell me about your role in the organization, particularly as it relates to talent acquisition, development, or management?

- Please describe your organization briefly (industry, size, structure) and the types of positions for which you typically hire recent graduates.

- How important are educational credentials in your hiring processes? Has this changed over time?

- 4.

- Walk me through your typical hiring process for entry-level positions requiring a college degree. What are you looking for at each stage?

- 5.

- Beyond the degree itself, what educational experiences or achievements do you value most when evaluating candidates? Why?

- 6.

- How do you assess candidates' skills and competencies during the hiring process? What methods have proven most effective?

- 7.

- How important is institutional reputation or prestige in your hiring decisions? Are there particular institutions whose graduates you actively recruit? Why?

- 8.

- What role do internships, co-ops, or other experiential learning experiences play in your evaluation of candidates? Do you distinguish between different types or qualities of these experiences?

- 9.

- How do you view alternative credentials (certificates, badges, etc.) compared to traditional degrees? Has your perspective on this changed recently?

- 10.

- In your experience, how well does higher education generally prepare graduates for work in your organization? Where are the strengths and gaps?

- 11.

- What specific skills or competencies do you find are typically well-developed in recent graduates? Which are typically underdeveloped?

- 12.

- Have you observed differences in workplace readiness or performance based on graduates' fields of study? Based on institution type?

- 13.

- What challenges do recent graduates typically face in transitioning to your workplace? How does your organization address these challenges?

- 14.

- How long does it typically take for a recent graduate to become fully productive in your organization? What factors influence this timeline?

- 15.

- Have you observed differences in how educational credentials translate into workplace success across demographic groups (gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background)?

- 16.

- What steps does your organization take to ensure equitable assessment of candidates from diverse educational backgrounds?

- 17.

- How do you address potential biases related to institutional prestige or educational pathways in your hiring and development processes?

- 18.

- Does your organization partner with educational institutions? If so, how? What motivates these partnerships?

- 19.

- What challenges have you encountered in developing or maintaining educational partnerships? How have you addressed these challenges?

- 20.

- Have you or your organization provided input to educational institutions about curriculum or program design? If so, how responsive have institutions been to this input?

- 21.

- Does your organization provide educational benefits or learning opportunities for employees? How do these complement or supplement formal higher education?

- 22.

- How has technology changed the relationship between educational credentials and employment in your field?

- 23.

- How are automation, artificial intelligence, or other technological changes affecting skill requirements in your organization? How well is higher education adapting to these changes?

- 24.

- What emerging hiring or assessment practices do you see affecting the education-employment relationship?

- 25.

- Based on your experience, what changes would you recommend to higher education institutions to better prepare graduates for employment success?

- 26.

- What advice would you give to students about maximizing the employment value of their educational experiences?

- 27.

- How could policy changes improve the connection between education and employment outcomes?

- 28.

- How do you see the relationship between educational credentials and employment evolving over the next 5-10 years?

- 29.

- Is there anything else about the education-employment relationship that you'd like to share that we haven't covered?

- 30.

- Do you have any questions for me about this research?

- Could you tell me about your role at your institution, particularly as it relates to curriculum, program design, or student career development?

- Please describe your institution briefly (type, size, mission) and its approach to preparing students for post-graduation success.

- How does your institution or program conceptualize the relationship between education and employment? Has this changed over time?

- 4.

- How does employment preparation factor into curriculum design and program development at your institution? At what levels does this occur (institutional, college, department)?

- 5.

- What specific educational practices or experiences at your institution are designed to enhance employment outcomes? How do you assess their effectiveness?

- 6.

- How are experiential learning opportunities (internships, co-ops, service learning, etc.) integrated into the educational experience? What challenges do you face in implementing these effectively?

- 7.

- How does your institution approach the development and documentation of skills and competencies beyond traditional academic knowledge?

- 8.

- What role does career services play at your institution? How integrated is career development with academic programs?

- 9.

- How does your institution help students develop professional networks and social capital? Are there particular strategies for supporting first-generation or underrepresented students in this area?

- 10.

- What institutional factors facilitate or hinder efforts to strengthen connections between education and employment?

- 11.

- How do faculty incentive structures and reward systems affect engagement with employment-oriented educational practices?

- 12.

- What tensions or tradeoffs do you perceive between employment preparation and other educational objectives (e.g., intellectual development, civic engagement, personal growth)?

- 13.

- How do accreditation requirements, disciplinary norms, or other external factors influence your approach to employment preparation?

- 14.

- How does your institution track and use data on graduate employment outcomes? How does this information influence program decisions?

- 15.

- How does your institution or program engage with employers? What forms do these relationships take?

- 16.

- What challenges have you encountered in developing or maintaining employer partnerships? How have you addressed these challenges?

- 17.

- How responsive is your institution to changing employer needs or labor market trends? What mechanisms exist for incorporating this information into educational offerings?

- 18.

- How do you balance employer input with academic values and institutional mission in program design and implementation?

- 19.

- How does your institution address disparities in employment outcomes across different student populations?

- 20.

- What specific initiatives exist to support equitable access to career-enhancing experiences like internships, particularly for students from disadvantaged backgrounds?

- 21.

- How do you view the role of higher education in either reducing or reinforcing existing social and economic inequalities through the education-employment relationship?

- 22.

- How is technology changing the relationship between education and employment in your field or institution?

- 23.

- How is your institution responding to emerging forms of credentials and alternative educational pathways?

- 24.

- What innovations in teaching, learning, or assessment do you see as most promising for improving the education-employment connection?

- 25.

- What do you see as the most significant challenges in strengthening the relationship between higher education and employment outcomes?

- 26.

- What policy changes would better support effective education-employment connections?

- 27.

- How do you envision the future relationship between higher education and employment? What implications might this have for institutional missions and practices?

- 28.

- What research questions about the education-employment relationship do you believe are most pressing?

- 29.

- Is there anything else about the education-employment relationship that you'd like to share that we haven't covered?

- 30.

- Do you have any questions for me about this research?

References

- Autor, D. (2020). The faltering escalator of urban opportunity. In M. Strain (Ed.), The U.S. labor market: Status, challenges, and opportunities (pp. 108-136). Brookings Institution Press.

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. University of Chicago Press. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2018). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (5th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Carnevale, A. P., Cheah, B., & Wenzinger, E. (2021). The college payoff: More education doesn't always mean more earnings. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Deming, D. J. (2022). Four facts about human capital. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(3), 75-102.

- Deming, D. J., & Noray, K. L. (2020). STEM careers and the changing skill requirements of work. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(4), 1965-2005.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160. [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6pt2), 2134-2156. [CrossRef]

- Gillborn, D., & Youdell, D. (2000). Rationing education: Policy, practice, reform, and equity. Open University Press.

- Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549-576. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C., Tamborini, C. R., & Sakamoto, A. (2019). Field of study and the gender wage gap: Evidence from the SIPP and ACS. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 115(530), 1-16.

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340-363. [CrossRef]

- Oreopoulos, P., & Petronijevic, U. (2023). The remarkable unresponsiveness of college students to nudging and what we can learn from it. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 37(1), 189-210.

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355-374.

- Webber, D. A. (2014). The lifetime earnings premia of different majors: Correcting for selection based on cognitive, noncognitive, and unobserved factors. Labour Economics, 28, 14-23. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Study Sample (%) | National Population (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 58.4 | 56.2 |

| Male | 41.2 | 43.5 |

| Non-binary/Other | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 61.7 | 63.5 |

| Black | 15.3 | 13.4 |

| Hispanic | 14.6 | 15.2 |

| Asian | 6.8 | 6.5 |

| Other/Multiple | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| First-Generation Status | ||

| First-Generation | 33.8 | 32.5 |

| Continuing-Generation | 66.2 | 67.5 |

| Institution Type | ||

| Public Research | 28.6 | 29.3 |

| Public Comprehensive | 26.4 | 25.7 |

| Private Research | 12.5 | 11.8 |

| Private Comprehensive | 14.7 | 15.3 |

| Liberal Arts | 9.8 | 10.2 |

| Community College Transfer | 8.0 | 7.7 |

| Field of Study | ||

| STEM | 24.3 | 23.6 |

| Business | 19.6 | 20.2 |

| Social Sciences | 18.4 | 17.9 |

| Humanities | 14.7 | 15.4 |

| Health Professions | 13.2 | 12.8 |

| Education | 9.8 | 10.1 |

| Characteristic | Number | Percentage |

| Employers (n=32) | ||

| Industry Sector | ||

| Technology | 7 | 21.9% |

| Healthcare | 5 | 15.6% |

| Financial Services | 4 | 12.5% |

| Manufacturing | 4 | 12.5% |

| Professional Services | 4 | 12.5% |

| Nonprofit | 3 | 9.4% |

| Retail/Hospitality | 3 | 9.4% |

| Government | 2 | 6.2% |

| Organization Size | ||

| Small (<100 employees) | 10 | 31.3% |

| Medium (100-999) | 12 | 37.5% |

| Large (1000+) | 10 | 31.3% |

| Position Level | ||

| C-Suite/Executive | 6 | 18.8% |

| Senior Management | 8 | 25.0% |

| HR/Talent Acquisition | 14 | 43.8% |

| Line Management | 4 | 12.5% |

| Higher Education Stakeholders (n=28) | ||

| Institution Type | ||

| Research University | 9 | 32.1% |

| Comprehensive University | 8 | 28.6% |

| Liberal Arts College | 6 | 21.4% |

| Community College | 5 | 17.9% |

| Role | ||

| Faculty | 12 | 42.9% |

| Administrator | 8 | 28.6% |

| Career Services | 8 | 28.6% |

| Academic Area | ||

| STEM | 7 | 25.0% |

| Business/Economics | 6 | 21.4% |

| Humanities | 5 | 17.9% |

| Social Sciences | 5 | 17.9% |

| Professional Programs | 5 | 17.9% |

| Recent Graduates (n=27) | ||

| Graduation Year | ||

| 2016-2018 | 12 | 44.4% |

| 2019-2021 | 15 | 55.6% |

| Field of Study | ||

| STEM | 8 | 29.6% |

| Business | 6 | 22.2% |

| Social Sciences | 5 | 18.5% |

| Humanities | 4 | 14.8% |

| Health/Education | 4 | 14.8% |

| Demographics | ||

| Female | 15 | 55.6% |

| Male | 12 | 44.4% |

| White | 14 | 51.9% |

| Black | 5 | 18.5% |

| Hispanic | 5 | 18.5% |

| Asian | 3 | 11.1% |

| First-Generation | 11 | 40.7% |

| Category | Annual Salary ($) | Employment Rate (%) | Job Satisfaction (1-5) | Job-Education Alignment (1-5) | Career Progression Index |

| Field of Study | |||||

| STEM | 82,100 | 94.8 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 0.83 |

| Business | 78,400 | 93.5 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.78 |

| Health Professions | 76,800 | 96.2 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 0.75 |

| Social Sciences | 74,100 | 91.6 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 0.72 |

| Humanities | 71,500 | 90.3 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 0.68 |

| Education | 62,000 | 94.5 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 0.65 |

| Institution Type | |||||

| Highly Selective Private | 86,300 | 95.2 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.87 |

| Highly Selective Public | 81,700 | 94.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.83 |

| Moderately Selective Private | 77,200 | 93.5 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.76 |

| Moderately Selective Public | 73,500 | 92.1 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.73 |

| Less Selective Private | 68,400 | 90.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 0.68 |

| Less Selective Public | 65,700 | 89.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.65 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 79,600 | 93.2 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 0.78 |

| Female | 70,100 | 92.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.73 |

| Non-binary/Other | 72,400 | 91.5 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.71 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 77,500 | 93.6 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.77 |

| Asian | 79,800 | 94.2 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.79 |

| Hispanic | 69,000 | 91.8 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.71 |

| Black | 66,700 | 90.3 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 0.68 |

| Other/Multiple | 71,300 | 92.1 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.73 |

| First-Generation Status | |||||

| First-Generation | 68,900 | 91.3 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.69 |

| Continuing-Generation | 78,300 | 93.7 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.79 |

| High-Impact Experiences | |||||

| High-Quality Internship | 82,600 | 95.3 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 0.84 |

| Any Internship | 75,800 | 93.4 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.76 |

| No Internship | 68,300 | 89.2 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 0.65 |

| Strong Skills Documentation | 79,400 | 94.5 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 0.80 |

| Limited Skills Documentation | 70,600 | 91.2 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 0.70 |

| Predictor | Annual Salary | Job Satisfaction | Job-Education Alignment | Career Progression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | B | β | B | β | B | β | B | |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||||

| Female (vs. Male) | -0.09*** | -7,462*** | 0.02 | 0.04 | -0.01 | -0.02 | -0.06** | -0.11** |

| Black (vs. White) | -0.07** | -5,793** | -0.04* | -0.08* | -0.03 | -0.06 | -0.05* | -0.09* |

| Hispanic (vs. White) | -0.06** | -4,965** | -0.03 | -0.06 | -0.02 | -0.04 | -0.04* | -0.07* |

| Asian (vs. White) | 0.04* | 3,312* | -0.02 | -0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| First-Generation Status | -0.08*** | -6,618*** | -0.04* | -0.08* | -0.03 | -0.06 | -0.06** | -0.11** |

| Socioeconomic Status (z-score) | 0.09*** | 7,442*** | 0.05* | 0.10* | 0.04* | 0.08* | 0.07** | 0.13** |

| Institutional Characteristics | ||||||||

| Institutional Selectivity | 0.07** | 5,793** | 0.04* | 0.08* | 0.05* | 0.10* | 0.06** | 0.11** |

| Private Institution (vs. Public) | 0.03 | 2,484 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Institution Size (1000s) | 0.01 | 828 | -0.01 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Academic Performance | ||||||||

| Cumulative GPA | 0.10*** | 8,270*** | 0.07** | 0.14** | 0.09*** | 0.18*** | 0.08*** | 0.15*** |

| Honors Distinction | 0.05* | 4,135* | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04* | 0.08* | 0.04* | 0.07* |

| Educational Experiences | ||||||||

| High-Quality Internship | 0.24*** | 19,848*** | 0.25*** | 0.50*** | 0.28*** | 0.56*** | 0.26*** | 0.47*** |

| Basic Internship | 0.08** | 6,616** | 0.09*** | 0.18*** | 0.12*** | 0.24*** | 0.09*** | 0.16*** |

| Skills Documentation | 0.18*** | 14,886*** | 0.14*** | 0.28*** | 0.23*** | 0.46*** | 0.16*** | 0.29*** |

| Career-Integrated Curriculum | 0.16*** | 13,232*** | 0.21*** | 0.42*** | 0.19*** | 0.38*** | 0.18*** | 0.32*** |

| Professional Network Development | 0.19*** | 15,713*** | 0.16*** | 0.32*** | 0.15*** | 0.30*** | 0.20*** | 0.36*** |

| Interaction Terms | ||||||||

| High-Quality Internship × First-Gen | 0.14** | 11,578** | 0.12** | 0.24** | 0.13** | 0.26** | 0.15** | 0.27** |

| High-Quality Internship × URM | 0.16** | 13,232** | 0.13** | 0.26** | 0.14** | 0.28** | 0.17** | 0.31** |

| Network Access × First-Gen | 0.12** | 9,924** | 0.10* | 0.20* | 0.09* | 0.18* | 0.13** | 0.23** |

| Race × SES | 0.09** | 7,443** | 0.07* | 0.14* | 0.08* | 0.16* | 0.10** | 0.18** |

| Model Statistics | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.40 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.38 | ||||

| F-statistic | 28.76*** | 24.31*** | 21.43*** | 26.52*** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).