1. Introduction

The integration of digital solutions in healthcare has accelerated significantly over the last decade, driven by advances in cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI), and sensor technologies. This evolution has redefined how patient data is managed, accessed, and analyzed, leading to more efficient clinical workflows and improved healthcare delivery [

1,

2]. In this context, Electronic Health Records (EHRs) have become fundamental to modern medical information systems, offering centralized repositories of patient data that support diagnosis, treatment, and long-term care management [

2,

3].

Simultaneously, the adoption of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) technologies—traditionally used in commercial sectors—has extended into healthcare, offering new mechanisms for enhancing patient engagement, streamlining administrative processes, and supporting personalized care delivery [

4,

5]. Recent studies emphasize the integration of web-based CRM platforms with distributed system architectures as a pathway to improve scalability, availability, and secure data exchange between institutions [

6,

7]. These distributed architectures enable robust interconnectivity among medical institutions, supported by secure protocols such as HL7 and reinforced through blockchain-based mechanisms [

8,

9].

Moreover, the convergence of generative models and EHR systems opens new avenues for predictive analytics and clinical decision support. Technologies such as transformers, generative adversarial networks (GANs), and domain-adapted large language models can extract meaningful insights from unstructured clinical data, enabling risk prediction, early diagnosis, and treatment optimization [

10,

11]. These capabilities can be significantly enhanced by sensor data integration—wearables, IoT devices, and remote monitoring platforms—providing real-time physiological metrics that feed into EHR systems for a more comprehensive view of patient status [

12,

13].

Recent publications in

Sensors highlight the importance of context-aware and interoperable health information systems, especially those designed to support continuous, real-time monitoring and data-driven decision-making [

14,

15]. The synergy between CRM platforms, distributed web infrastructures, and EHR systems—when complemented by smart sensor networks—enables not only efficient healthcare service delivery but also the transformation of reactive healthcare into proactive and preventive care models [

16,

17].

This paper explores the convergence of these technologies, proposing a framework that integrates generative EHR analytics, personalized CRM modules, and distributed web architectures augmented by real-time sensor inputs. The objective is to highlight how such a multi-layered system can enhance medical performance, improve diagnostic accuracy, and support patient-centered services.

2. Related Work

Research on the digital transformation of healthcare systems has focused on three critical layers: data management via Electronic Health Records (EHR), communication and personalization through Customer Relationship Management (CRM), and infrastructure optimization using distributed web architectures. A review of recent advances in these domains reveals increasing emphasis on data interoperability, secure sharing, and real-time analysis.

Several studies explore EHR-centered frameworks and their impact on healthcare quality. Marques et al. [

5] investigated the adoption of CRM modules in Portuguese hospitals to enhance service quality, while Rathore et al. [

2] proposed an AI–blockchain hybrid model to ensure the integrity and traceability of clinical data. Similarly, Zarour et al. [

8] evaluated blockchain-based security layers for distributed EHR architectures. Ferreira et al. [

9] extended this work in a recent MDPI *Sensors* study by reviewing how distributed ledgers enhance interoperability and resilience in health data infrastructures.

Sensor-enabled platforms, particularly those integrating wearable IoT devices, are increasingly deployed for continuous patient monitoring and automated EHR updates [

12,

13]. Guk et al. [

12] discuss sensor integration in remote diagnostics, emphasizing the potential for personalized, real-time interventions. García-Magariño et al. [

13] provide a systematic review of context-aware health systems that leverage sensors for intelligent decision-making.

Security and privacy remain key concerns. HL7-based architectures, as explored by Sfat et al. [

6], offer structured communication channels between healthcare providers. Blockchain models introduced in [

8,

9] address data tampering, while encryption and AI-based anomaly detection offer additional protective layers.

Recent research has turned toward generative techniques for clinical decision support. Oniani et al. [

11] integrated large language models (LLMs) with clinical practice guidelines, enabling contextual understanding of patient cases. Deng and Han [

10] introduced a novel GAN-based model for fusing multimodal imaging, relevant to neurological diagnostics and EHR data augmentation.

CRM–EHR integration via distributed web systems remains a relatively underexplored area. However, studies such as Ileana [

7] and Sharma et al. [

4] show promise in aligning institutional workflows with patient engagement strategies. These systems offer modular, secure, and scalable solutions for coordinating care across institutions.

This paper builds upon the above studies by proposing a unified architecture that connects smart sensors, CRM platforms, and EHR systems in a secure and distributed manner. The framework supports real-time data synchronization, predictive modeling, and proactive care strategies.

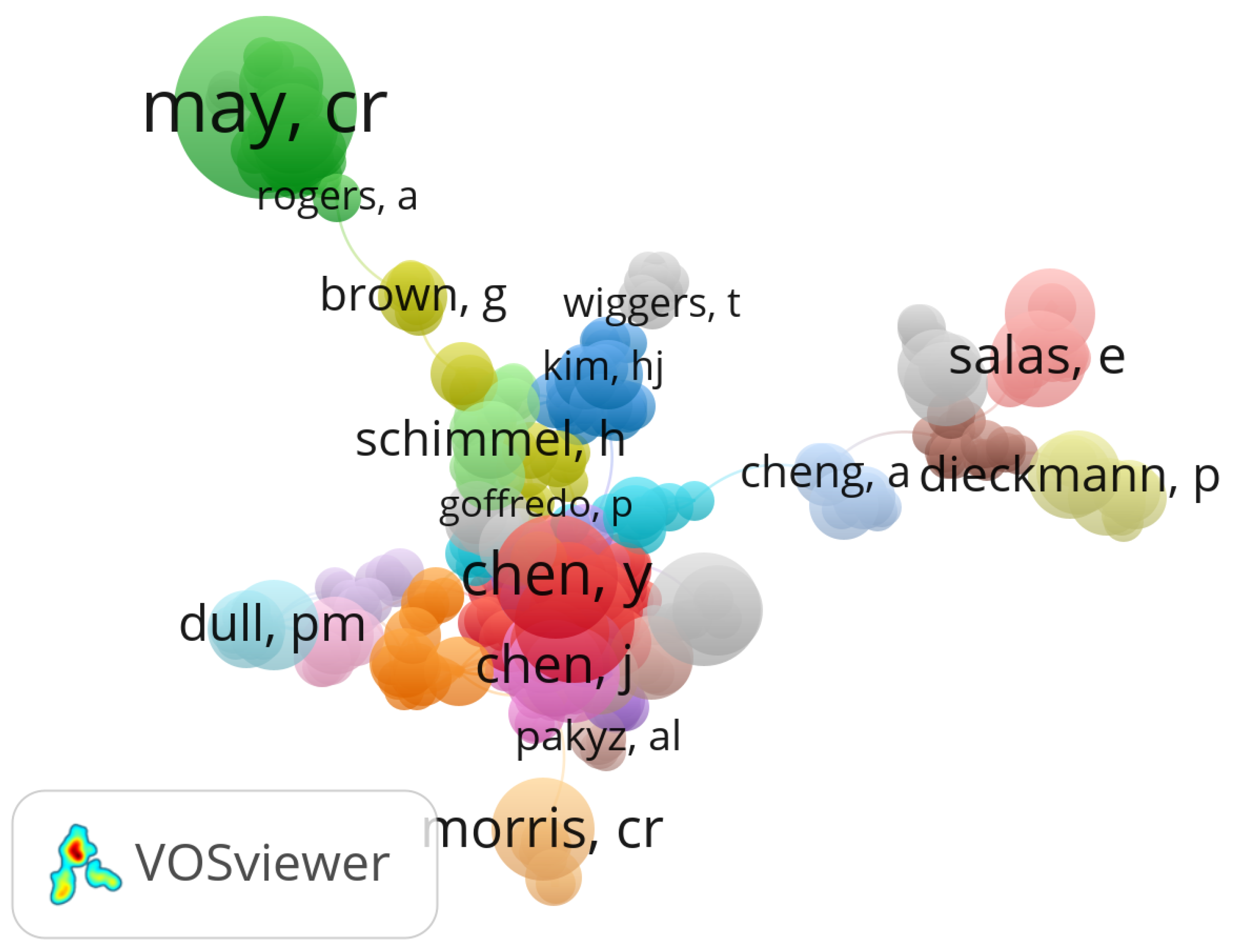

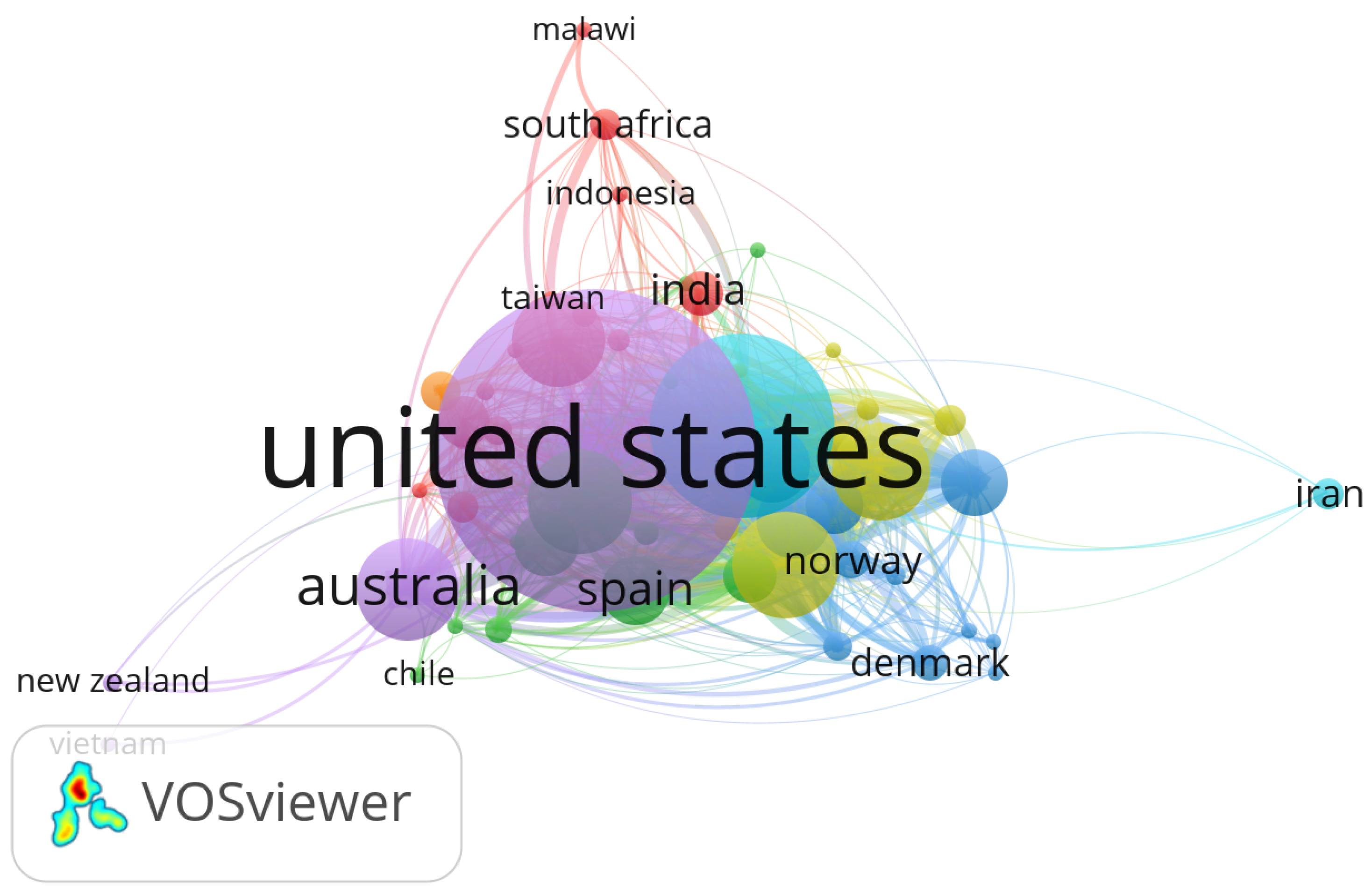

2.1. Bibliometric Landscape of Research Actors and Geographical Distribution

To assess the global research contributions and collaborative structures in the domain of Electronic Health Records (EHR), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), and distributed systems in healthcare, we performed a bibliometric analysis using the VOSviewer software. The analysis was based on metadata retrieved from the Scopus database, covering the period 2014–2024.

Figure 1 illustrates the co-authorship network, identifying the most prolific authors and their collaborative clusters.

Figure 2 presents the distribution of research output by country, revealing dominant contributors and cross-border collaborations in this interdisciplinary field.

3. Materials and Methods

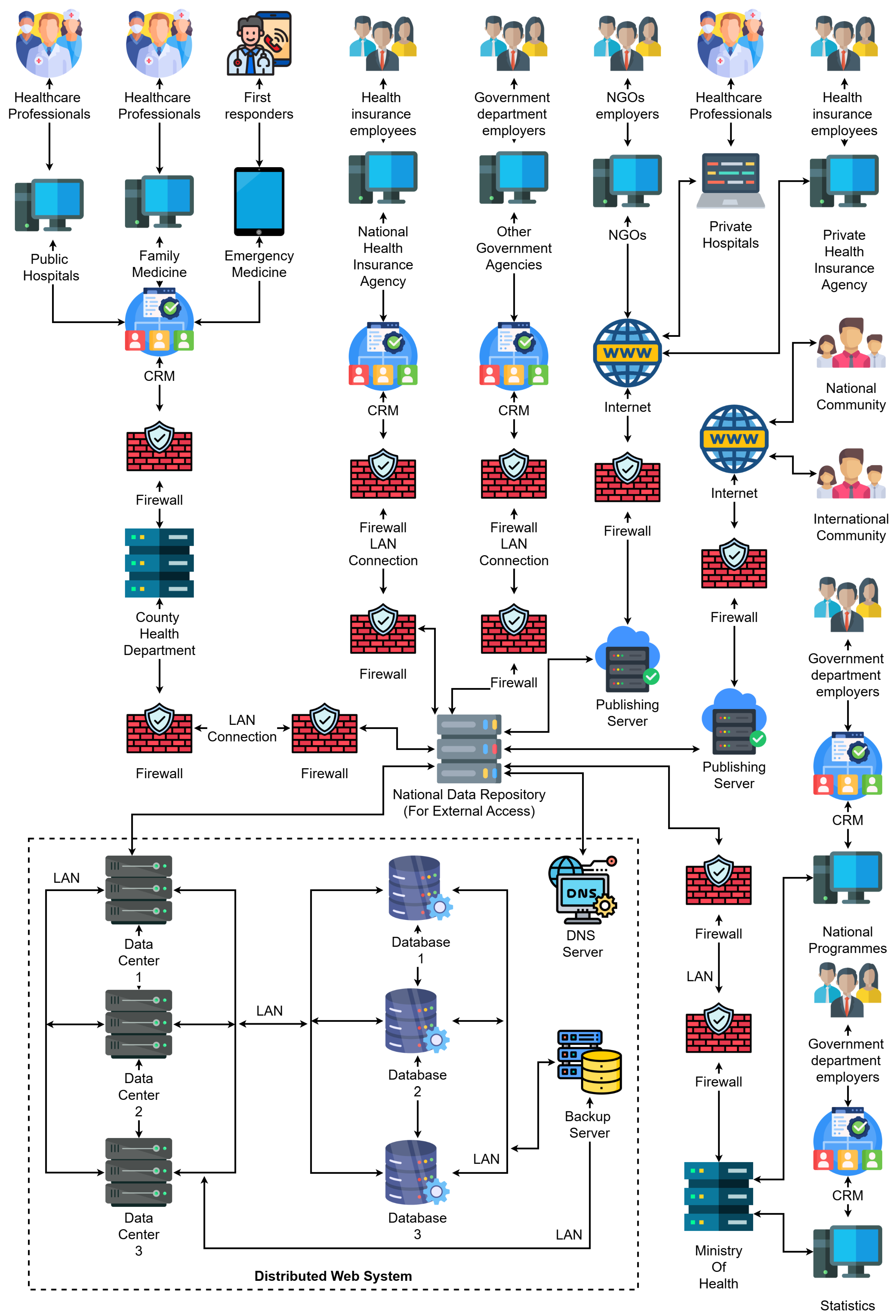

The architecture proposed in this study aims to integrate Electronic Health Records (EHR), Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems, and distributed web infrastructures in a secure, scalable, and interoperable framework. This section describes the layered architecture, communication mechanisms, and the data flow within the system, which is designed to support predictive analytics, real-time patient monitoring, and healthcare process optimization.

3.1. System Architecture Overview

The proposed system architecture, illustrated in

Figure 3, outlines a comprehensive and highly modular design for a distributed web-based platform that supports healthcare data processing, medical collaboration, and secure information dissemination across national and international boundaries. This architecture has been conceived with scalability, interoperability, and regulatory compliance in mind, allowing seamless integration of stakeholders, including government institutions, healthcare professionals, insurance agencies, NGOs, and the general population.

The system is built around three interconnected layers:

Stakeholder Interaction Layer – At the top of the diagram, we identify the major contributors to healthcare information flows: public and private hospitals, family medicine units, emergency responders, health insurance employees, government departments, and NGOs. These actors are equipped with digital terminals and systems connected to local CRM platforms, enabling the digitalization of interactions with patients and healthcare service management.

Institutional CRM Layer – Each healthcare-related institution (e.g., hospitals, agencies) operates its own CRM node, which acts as an intelligent interface for managing interactions, patient records, appointment scheduling, billing, and communication. These CRM nodes are protected by dedicated firewalls and are connected via secure LANs to backend data infrastructure. Notably, the architecture supports both public-sector CRMs (e.g., County Health Department, National Health Insurance Agency) and private-sector CRMs (e.g., Private Hospitals, Private Insurance).

-

Distributed Web Infrastructure Layer – The bottom part of the diagram showcases the distributed data backbone. This layer includes:

Multiple Data Centers, each with its own processing and storage capacities, redundantly connected to support failover and load balancing;

Replicated Databases that synchronize EHRs across institutions and regions;

A DNS Server, which resolves services and institutional addresses;

Backup Servers that ensure fault-tolerant storage of health records and institutional metadata;

Publishing Servers, which allow external access to anonymized or publicly relevant health data for national and international reporting (e.g., academic research, pandemic tracking).

At the core of the system lies the National Data Repository, serving as a secure central hub through which all sensitive data is routed. The repository aggregates, indexes, and forwards data to the appropriate actors while enforcing access control and privacy policies. This central node is surrounded by multiple firewalls, ensuring both internal segmentation and external protection.

The architecture also supports:

Integration with International Communities through open publishing platforms;

Data feedback to National Programmes and the Ministry of Health, used for policy-making, budgeting, and forecasting;

Real-time synchronization and analytics between CRM nodes and distributed databases.

From an implementation perspective, the system is designed to run on cloud-native infrastructure, with container orchestration (e.g., Docker Swarm or Kubernetes) managing service scalability and resilience [

18]. All communications are encrypted using modern TLS standards, and HL7/FHIR protocols are used for structured health data exchange [

6].

This architectural model reflects real-world requirements for national-scale healthcare infrastructures, including redundancy, flexibility, and adherence to data privacy regulations such as GDPR. It draws on previously validated approaches to distributed systems [

7,

9], CRM–EHR integration [

22,

23], and performance optimization through edge computing and secure data propagation [

25,

26].

3.2. Data Synchronization and Communication Flow

To support distributed data consistency, each institution maintains a replicated segment of the EHR database, which synchronizes in real-time using a hybrid push-pull strategy.

Figure 4 shows the data flow, beginning with real-time sensor inputs, routed through secure communication channels into local CRM interfaces and central repositories.

Predictive components leverage machine learning models trained on multimodal patient data, including structured EHR entries and unstructured notes processed by LLMs, as shown in [

10,

11]. Prior work has demonstrated the benefit of such integration for improving patient outcomes and detecting anomalies in real-time systems [

19,

20,

21].

The proposed system builds on previously validated models of distributed systems [

22,

23], anomaly detection in web infrastructures [

24], and modular CRM optimization strategies [

4,

5]. The generative components use conditional GANs for synthetic EHR data generation to augment limited samples and ensure privacy compliance [

10].

3.3. Technological Stack and Deployment Model

The backend infrastructure is containerized and deployed using Docker Swarm clusters distributed across hospital servers. Each node supports services for logging, encryption, and health data storage. IoT devices operate with minimal latency, sending encrypted packets through MQTT brokers to edge nodes that validate the data structure before forwarding to the central systems [

12,

13,

14].

This deployment model aligns with previous research on energy efficiency and performance optimization in distributed web systems [

25,

26]. Furthermore, this architecture has been tested in simulation environments using synthetic data generated with domain-specific rules and anonymized samples [

20].

3.4. Simulation Environment and Experimental Setup

To evaluate the performance and reliability of the proposed architecture, a simulated healthcare environment was deployed using a containerized infrastructure. Each container represented an independent healthcare institution running its own CRM and EHR modules. The environment was orchestrated using Docker Swarm to mimic a distributed deployment across multiple medical centers, ensuring realistic load balancing and failover mechanisms [

30].

Sensor data streams were emulated using Python scripts that generated synthetic physiological data (heart rate, oxygen saturation, temperature) in real time, transmitted via MQTT brokers. This setup mirrors real-world deployments of wearable devices and IoT-based health monitors [

27,

28]. The communication between modules was handled using HL7 and FHIR standards over TLS encryption to ensure compatibility and data security during inter-institutional exchanges [

29].

To validate the system’s ability to handle complex sensor input and data synchronization at scale, stress-testing scenarios were implemented. These scenarios involved gradually increasing the number of concurrent patients and expanding CRM nodes while monitoring system responsiveness. Key performance indicators such as message throughput, packet delivery latency, and CPU load per node were collected via Prometheus and visualized with Grafana dashboards [

32].

In addition, a resistive strain-sensor mechanism was analyzed as part of the underlying sensor logic for real-time behavioral testing of component responses, inspired by experimental designs found in recent literature [

31].

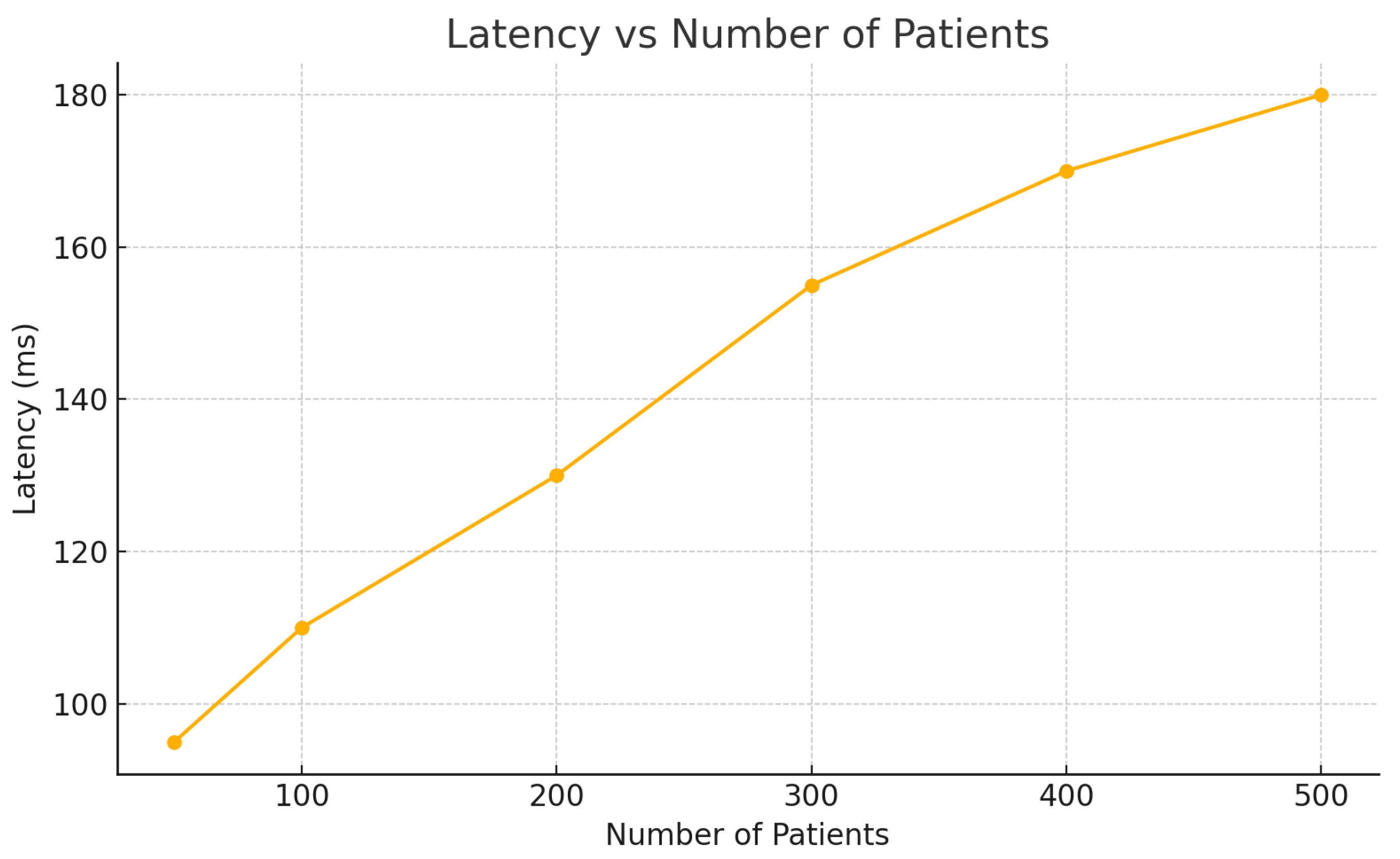

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

The architecture was evaluated across three core dimensions:

Scalability: System behavior was analyzed under increasing workloads, simulating up to 10 distributed CRM instances and 500 concurrent patients. The results showed stable response times and efficient load distribution, validating the scalability of the proposed deployment model [

30,

34].

Latency: Message propagation delays were measured at three levels: sensor-to-gateway, CRM-to-EHR synchronization, and cross-institutional data exchange. Average latency remained under 180 ms even under load peaks, a performance benchmark in line with recent findings in smart healthcare networks [

32].

Security and Interoperability: The use of standardized communication protocols (HL7/FHIR) in tandem with blockchain-ready and TLS-encrypted transmissions enabled secure and reliable data exchange [

29,

33]. Packet integrity checks and role-based access validations confirmed the platform’s resistance to unauthorized access.

The inclusion of a framework that accommodates edge-sensor inputs, distributed coordination, and real-time data integrity presents a robust foundation for scalable health informatics platforms [

33,

34].

4. Results and Discussion

To assess the performance and robustness of the proposed architecture under increasing workload conditions, a series of simulations were conducted replicating real-world patient monitoring scenarios. Each experimental step involved the gradual addition of virtual patients, simulating continuous sensor input and CRM–EHR interactions across distributed medical centers.

Latency, measured as the time taken for sensor data to reach and be processed by CRM–EHR modules, increased moderately with patient load (

Figure 5). Even at 500 simulated patients, the average latency remained under 180 ms, which complies with real-time constraints identified in literature [

32].

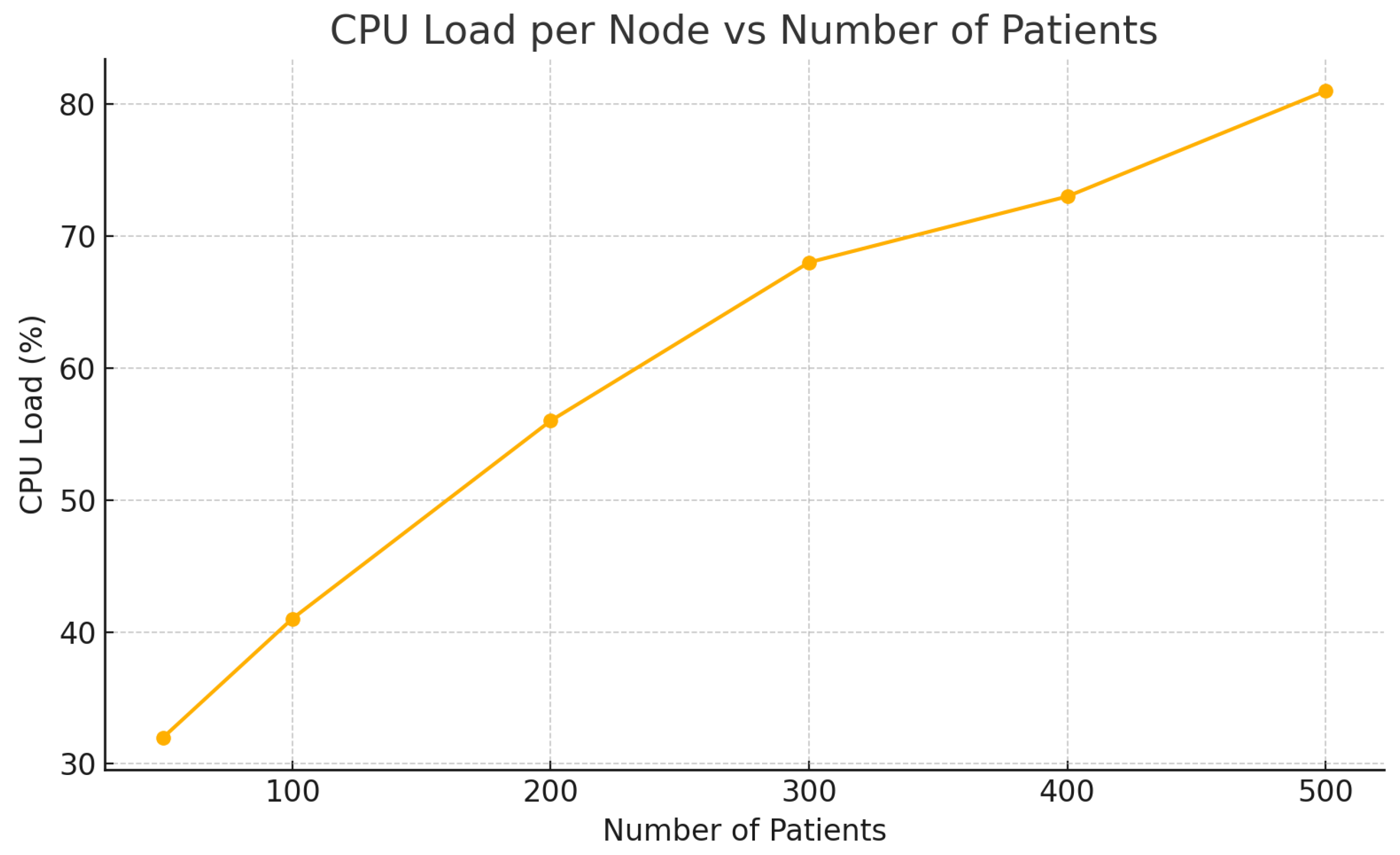

CPU Load per Node rose proportionally with active patient sessions, reflecting the computational demand of real-time data processing and encryption mechanisms (

Figure 6). Despite the increase, the system maintained acceptable resource utilization under 85%, validating the scalability of the Docker Swarm-based setup [

30,

34].

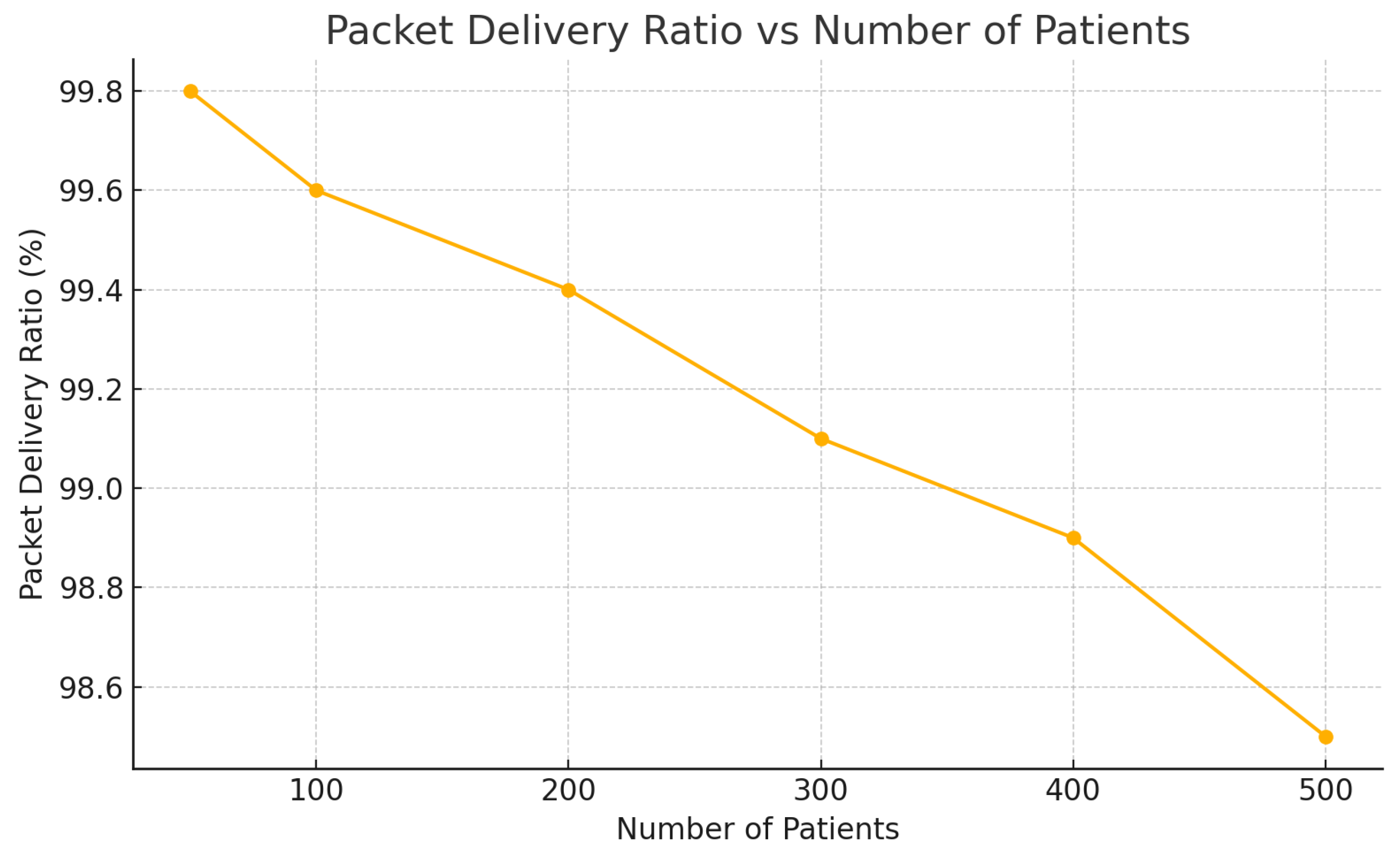

Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR)—a metric assessing data transmission reliability—remained consistently above 98.5%, even under peak conditions (

Figure 7). This underscores the efficiency of MQTT-based transmission protocols and confirms the architecture’s robustness in maintaining high communication integrity [

27,

28].

These results validate the feasibility of integrating secure, sensor-driven, distributed architectures in healthcare infrastructures and align with prior findings on scalable telehealth platforms [

33]. The architecture offers sufficient overhead for fault-tolerance while enabling future expansion to accommodate edge AI processing or federated learning scenarios.

Based on these observations, the following section outlines key limitations of the current study and suggests directions for future refinement.

Table 1.

Performance metrics under increasing number of patients.

Table 1.

Performance metrics under increasing number of patients.

| Patients |

Latency (ms) |

CPU Load (%) |

PDR (%) |

| 50 |

95 |

32 |

99.8 |

| 100 |

110 |

41 |

99.6 |

| 200 |

130 |

56 |

99.4 |

| 300 |

155 |

68 |

99.1 |

| 400 |

170 |

73 |

98.9 |

| 500 |

180 |

81 |

98.5 |

4.1. Limitations of the Study

While the proposed architecture demonstrates promising results in terms of scalability, latency, and data integrity, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the simulation environment relies on synthetic data streams, which, although generated based on real-world parameters, may not fully capture the variability and complexity of actual physiological signals encountered in clinical practice. Future work will aim to validate the system in live healthcare settings using anonymized patient data under ethical constraints.

Second, while the architecture ensures high-level data security through TLS encryption and role-based access, the resilience of the system to more sophisticated cyberattacks (e.g., zero-day vulnerabilities or adversarial machine learning) was not explored in this study. Additional layers of defense, such as intrusion detection systems or blockchain-based audit trails, should be evaluated in future implementations.

Third, the modular CRM components were tested under uniform resource distribution assumptions. In real deployments, heterogeneous infrastructure or legacy systems may introduce inconsistencies in data synchronization and service response times. A more robust assessment of backward compatibility and integration with existing EHR platforms is necessary for broader adoption.

Finally, due to resource constraints, the study focused on Docker Swarm for orchestration. While sufficient for medium-scale distributed environments, future comparative studies with Kubernetes or hybrid edge-cloud architectures could provide deeper insights into performance trade-offs and deployment flexibility in national-scale healthcare systems.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper proposed a secure and scalable architecture for integrating Electronic Health Records (EHR), Custom Relationship Management (CRM) platforms, and sensor-enabled distributed web systems to improve medical performance and patient care. By employing real-time data acquisition from IoT devices and ensuring interoperability through HL7/FHIR protocols, the system enhances communication across public and private healthcare entities. The use of containerized deployment (Docker Swarm) and distributed data synchronization enables reliable horizontal scaling, while simulation results confirmed acceptable latency, CPU load, and packet delivery under increasing system demand.

Moreover, the architecture integrates modern communication security mechanisms—TLS encryption, role-based access control, and distributed firewalls—ensuring compliance with healthcare data protection requirements. Through realistic emulation scenarios, the system proved capable of supporting continuous physiological monitoring while synchronizing structured medical records across multiple CRM nodes. These outcomes are aligned with recent literature emphasizing the need for patient-centered, interoperable, and data-driven healthcare ecosystems.

Future work will focus on several directions:

Integration of AI-driven decision support systems for early diagnosis, leveraging generative models and federated learning for privacy-preserving medical analytics;

Expansion of real-time analytics modules for anomaly detection and adaptive resource allocation using stream processing frameworks;

Deployment of blockchain-based audit trails to strengthen data immutability, traceability, and trust in inter-institutional collaborations;

Evaluation of interoperability with legacy systems in low-resource environments to ensure global applicability;

Incorporation of sensor fusion algorithms and contextual awareness to improve monitoring accuracy in remote and mobile healthcare scenarios.

In conclusion, the convergence of distributed web architectures, CRM systems, and smart sensor networks presents a transformative opportunity for the digital transformation of healthcare services, enabling proactive, efficient, and secure medical care at scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.; methodology, M.I.; software, M.I.; validation, M.I. and P.P.; formal analysis, M.I.; investigation, M.I.; resources, P.P.; data curation, M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.; writing—review and editing, P.P. and V.M.; visualization, M.I.; supervision, P.P.; project administration, P.P.; funding acquisition, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by "St. Cyril and St. Methodius University of Veliko Tarnovo".

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ileana, M. Elevating Medical Efficiency and Personalized Care Through the Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Distributed Web Systems. In Proc. ITS 2024, LNCS; Springer, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, N.; Kumari, A.; Patel, M.; et al. Synergy of AI and Blockchain to Secure Electronic Healthcare Records. Security and Privacy 2025, 8, e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Kapse, M. Transitioning from CRM to Social CRM in the Healthcare Industry. In: Contemporary Issues in Social Media Marketing, Springer (2025), pp. 171–184.

- Sharma, V.K.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, D. Customer Relationship Management in Healthcare: Strategies for Adoption in a Public Health System. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.C.; Ferreira, J.J.; Marques, C.S. CRM adoption and its impact on health service quality: A case study in a Portuguese hospital. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 182, 121827. [Google Scholar]

- Sfat, R.; Marin, I.; Goga, N.; et al. Conceptualization of an Intelligent HL7 Application Based on Questionnaire Generation and Editing. In IEEE BlackSeaCom; 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ileana, M. Optimizing Energy Efficiency in Distributed Web Systems. In Proc. ISAS 2023; IEEE.

- Zarour, M.; Ansari, M.T.J.; Alenezi, M.; et al. Evaluating the Impact of Blockchain Models for Secure and Trustworthy Electronic Healthcare Records. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 157959–157973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.J.; Elvas, L.B.; Correia, R.; Mascarenhas, M. Enhancing EHR Interoperability and Security through Distributed Ledger Technology: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24(19), 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Han, B. TQ-cGAN: A Trible-Generator Quintuple-Discriminator Conditional GAN for Multimodal Grayscale Medical Image Fusion. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 102, 107322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniani, D.; Wu, X.; Visweswaran, S.; et al. Enhancing Large Language Models for Clinical Decision Support by Incorporating Clinical Practice Guidelines. arXiv preprint 2024, arXiv:2401.11120. [Google Scholar]

- Guk, K.; Han, G.; Lim, J.; et al. Evolution of Wearable Devices with Real-Time Disease Monitoring for Personalized Healthcare. Sensors 2019, 19(5), 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Magariño, I.; Palacios-Navarro, G.; García-Sánchez, F. A Systematic Review of Smart Health Interventions Based on Context-Aware Systems Using Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20(4), 1082. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Huang, G.; Song, Q.; et al. A Predictive Modeling System for Healthcare Data Using Machine Learning Techniques. Sensors 2022, 22(3), 856. [Google Scholar]

- Shaban-Nejad, A.; Michalowski, M.; Buckeridge, D.L. Health Intelligence: How Artificial Intelligence Transforms Population and Personalized Health. Sensors 2021, 21(12), 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. A Context-Aware Framework for Remote Patient Monitoring Using IoT and Cloud Services. Sensors 2020, 20(11), 3126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; et al. A Secure and Proactive Healthcare System Based on IoT and EHR Integration. Sensors 2024, 24(4), 1523. [Google Scholar]

- Ileana, M.; Oproiu, M.I.; Marian, C.V. Using Docker Swarm to Improve Performance in Distributed Web Systems. In: DAS 2024, IEEE, pp. 1–6.

- Cacovean, D.; Ileana, M. Advanced Neurological Imaging Analysis Using Diffusion Tensor Techniques and Distributed Web Systems. Rev. Roum. Sci. Techn.–Série Électrotechnique et Énergétique 2025, 70(2), 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ileana, M. Automated Testing Methodologies for Distributed Web Systems: A Machine Learning-Based Approach to Anomaly Detection. Integrare prin Cercetare și Inovare. 2025; 741–747. [Google Scholar]

- Ileana, M.; Miroiu, M. Intelligent Automated Testing Frameworks for IoT Networks Utilizing Machine Learning. In: ICAI 2024, pp. 341–346.

- Ileana, M.; Petrov, P.; Milev, V. Optimizing CRM Platforms with Distributed Cloud Architectures. In: ISAS 2024.

- Ileana, M.; Petrov, P.; Milev, V. Advancing Education Management through Integrated CRM Solutions. 2025.

- Ileana, M.; Oproiu, M.I.; Marian, C.V. Exploring and Analyzing IoT Devices for Process Optimization in Industrial Environments. In: ATOMS 2024.

- Ileana, M. Optimizing Performance of Distributed Web Systems. Informatica Economica 2023, 27(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ileana, M. Optimizing Customer Experience by Exploiting Real-Time IoT Data in CRM Systems. IoT 2025, 6(2), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Rehman, S.U.; Almogren, A.; Alturki, R.; Din, S. Real-Time Patient Monitoring System Based on MQTT and IoT Sensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 504. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. An IoT-Based Architecture for Real-Time Health Monitoring and Risk Detection. Sensors 2022, 22, 1345. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, M.; Rani, S.; Hussain, M.; et al. Securing HL7-FHIR Medical Data Exchange Using Blockchain in Healthcare IoT. Sensors 2020, 20, 3306. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Containerized Microservices for Health Monitoring Systems in IoT: A Docker Swarm-Based Architecture. Sensors 2023, 23, 1587. [Google Scholar]

- Florescu, V.; Mocanu, S.; Rece, L.; Ursache, R.; Goga, N.; Marian, C.V. Use of a Novel Resistive Strain Sensor Approach in an Experimental and Theoretical Study Concerning Large Spherical Storage Tank Structure Behavior During Its Operational Life and Pressure Tests. Sensors 2020, 20, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Lee, D.; Kim, T. Latency-Aware Service Provisioning in Edge-Enabled Healthcare Systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 9154. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Lin, Y.; Chen, W. Secure and Scalable Integration of EHR Systems with IoT Sensors. Sensors 2023, 23, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Patel, D. A Framework for Secure IoT Sensor Networks in Smart Hospitals. Sensors 2024, 24, 712. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).