1. Introduction

Circoviruses are recognized as the smallest viruses known to infect animals. Four types of porcine circoviruses (PCV1–PCV4) have been sequentially identified in swine [

1]. Porcine circovirus type 1 (PCV1), initially identified as the first member of the porcine circovirus family, has been characterized as a nonpathogenic virus [

2]. PCV2 remains the main pathogen of related diseases. The pathogenicity of PCV3 remains controversial. PCV4 is a recently discovered pathogen, and its pathogenicity in pigs requires further investigation [

3,

4]. PCV2 infection causes porcine circovirus disease (PCVD), a global immunosuppressive disease in pigs. Its clinical manifestations include post-weaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS) and porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome (PDNS), which cause significant economic losses to the swine industry [

5,

6]. PCV2 is classified into 8 genotypes (PCV2a–PCV2h) [

7,

8]. Recently, a novel genotype, PCV2i, was identified [

9]. PCV2d is the predominant circulating subtype of PCV2 [

5]. The PCV2 genome is a covalently closed circular single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), approximately 1.7 kilobases (kb) [

10]. The software analysis identified 11 open reading frames (ORFs) in the PCV2 genome, but only 4 are utilized for protein expression [

11]. ORF2 encodes the sole structural protein - the capsid (Cap) protein. The Cap protein represents the primary antigenic determinant of the virus, which serves as a critical determinant of the host immune response and vaccine efficacy [

12].

For the prevention of PCVD, vaccination remains the primary strategy [

6]. Virus-like particles (VLPs), as a type of subunit vaccine, have emerged as the preferred candidate due to their lack of nucleic acids, inability to replicate autonomously, and enhanced safety profile. The Cap protein can self-assemble into VLPs across various expression systems [

13]. Although bacterial, yeast, and insect cell platforms are capable of expressing the Cap protein, commercially available vaccines (e.g., Ingelvac CircoFLEX

® and Circumvent

®) exclusively utilize the baculovirus-insect cell system [

14,

15,

16]. This preference is likely attributed to its advantages in high-yield production, appropriate post-translational modifications, and efficient VLP assembly. While alternative expression systems such as

E. coli and yeast are being explored for cost-effectiveness, they currently face challenges related to immunogenicity and scalability limitations [

17,

18].

The Bac-to-Bac and

flashBAC systems are two commonly commercialized baculovirus construction systems. Each system has its own advantages and limitations in terms of the operation procedures and application scope [

19,

20]. In the Bac-to-Bac system, the target gene is first cloned into a pFast series vector. The recombinant plasmid is then transformed into

E. coli DH10Bac competent cells to generate the bacmid through site-specific transposition. Positive clones are selected via blue-white screening, followed by bacmid extraction and transfection into insect cells for viral packaging (

Figure 1. A) [

21]. In contrast, the

flashBAC system employs compatible transfer vectors (e.g., pBAC or pOET series) to construct the expression cassette. The recombinant transfer vector is co-transfected with a linearized bacmid into insect cells, where homologous recombination occurs in vivo to generate the recombinant baculovirus directly (

Figure 1. B) [

19,

22]. Although both systems are commercial, laboratories choose one system based on their existing platform and research costs, seldom comparing the two systems side by side [

20]. Despite numerous studies have documented the application of both systems for Cap protein expression, applications of both systems in Cap protein expression, simultaneous expression comparisons remain unexplored. For certain proteins, increasing the gene copy number can enhance the expression level of recombinant proteins [

23,

24]. It remains unknown whether increasing the copy number of

cap gene enhances protein expression in the insect baculovirus system.

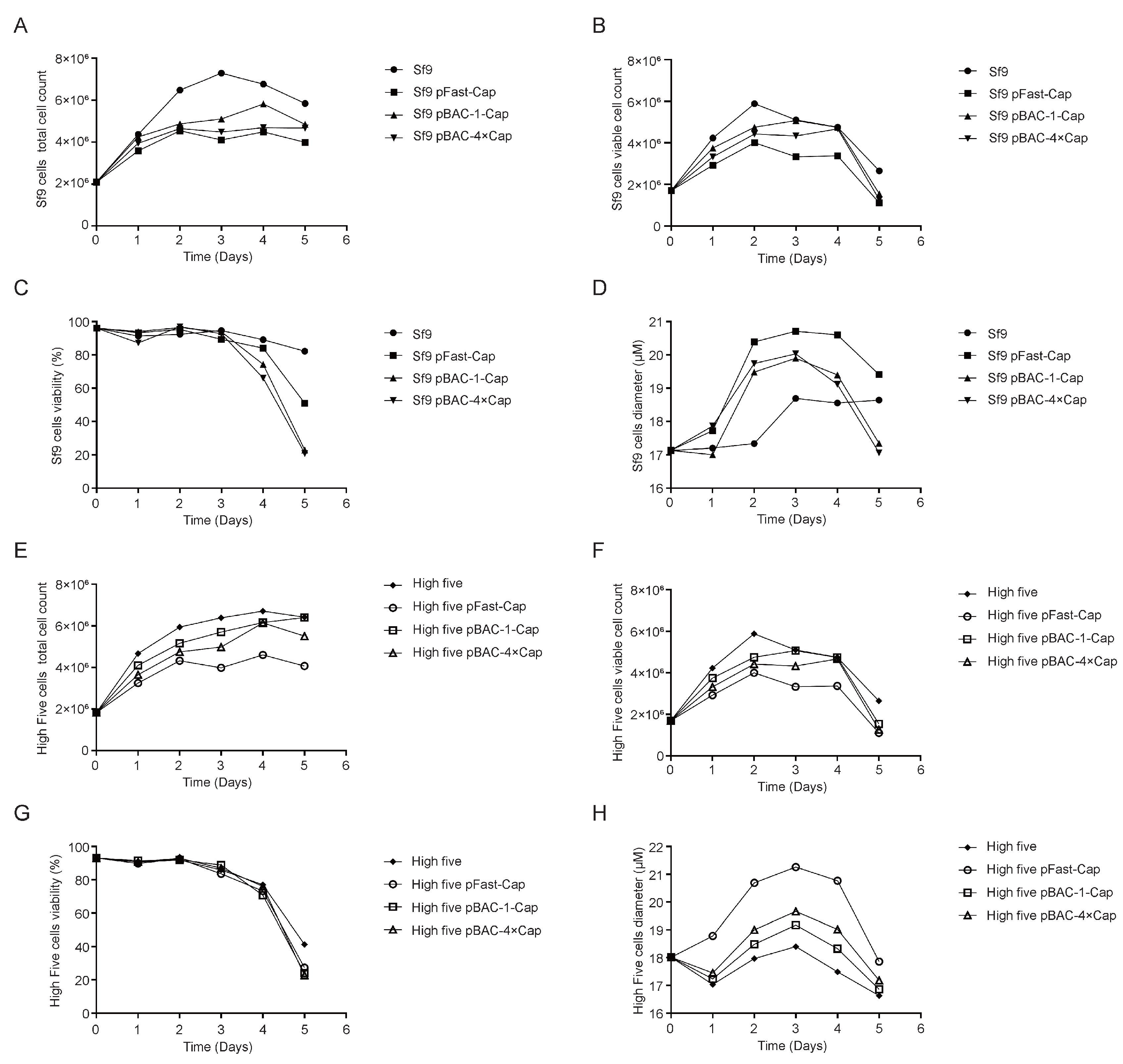

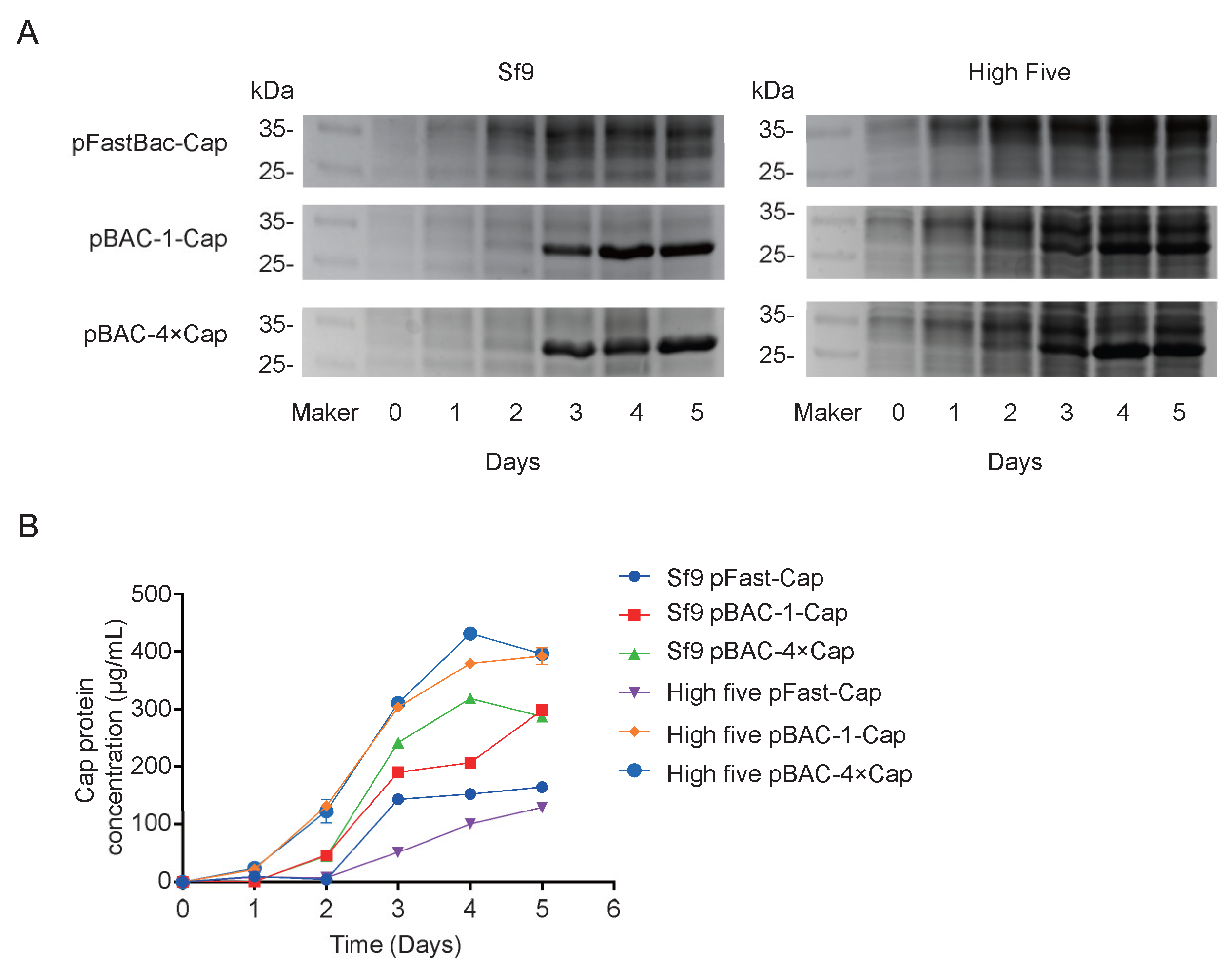

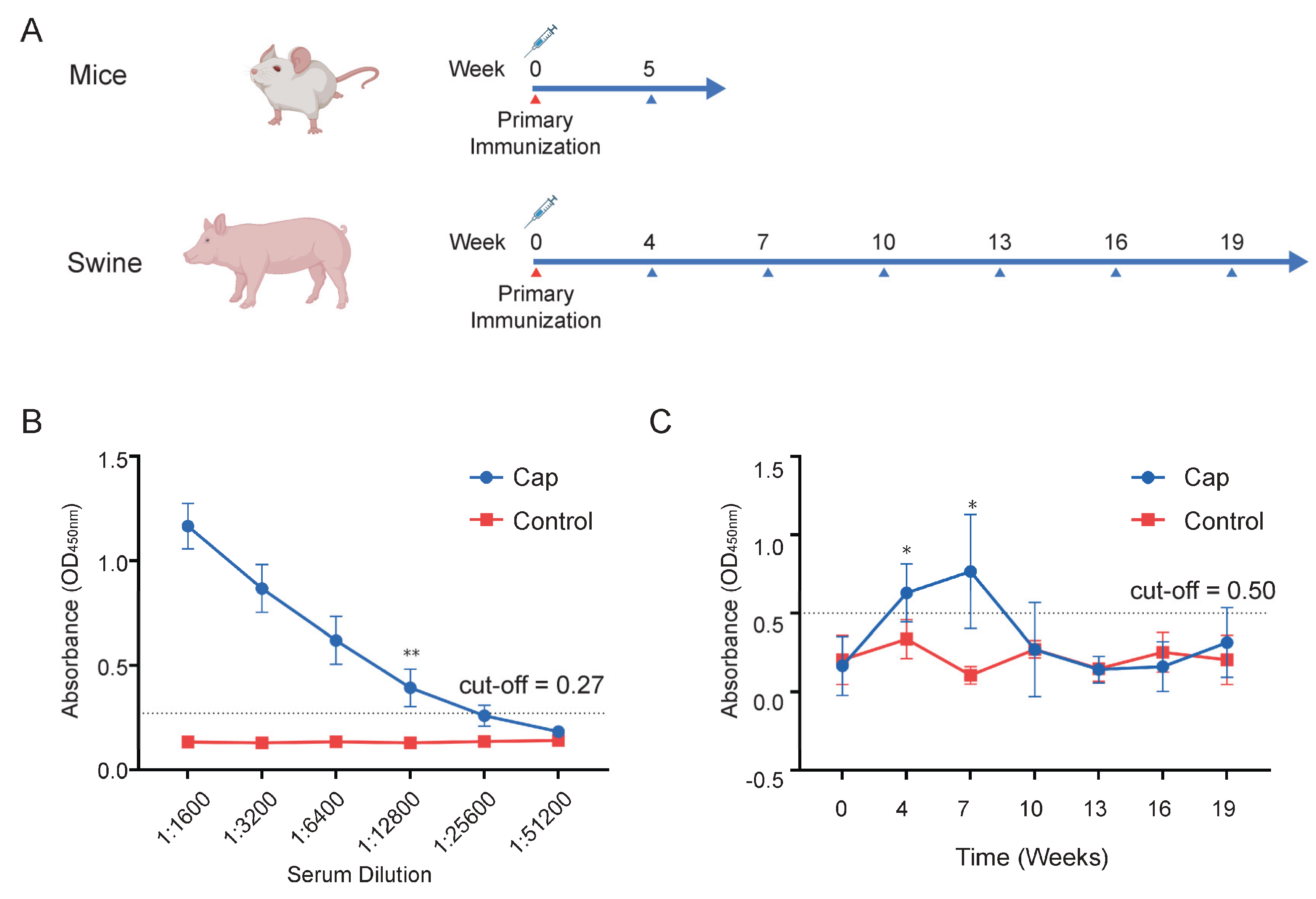

In this study, we compared two commonly commercialized baculovirus construction systems for expressing the Cap protein in various insect cells. Our findings demonstrated that the flashBAC system achieved significantly higher Cap protein expression levels compared to the Bac-to-Bac system, with increased gene copy number of the Cap protein further enhancing expression efficiency. High Five insect cells demonstrated superior performance for Cap protein expression compared to Sf9 cells. Notably, when expressing four copies of the Cap protein, the flashBAC system achieved the highest protein yield of 432 μg/mL in High Five cells. Animal immunization experiments confirmed that the expressed Cap protein effectively induced specific antibody production in both mice and swine. This study provides critical data for optimizing the production of PCV2 Cap protein, which is of great significance for cost reduction in porcine circovirus vaccine manufacturing.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Construction of Vectors

The target gene Cap (GenBank accession no. MK751862.1) was codon-optimized for expression in Spodoptera frugiperda cells and synthesized by Zhejiang Sunya Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Two expression systems were employed: the pFast-Dual vector (Bac-to-Bac system) and the pBAC-1 vector (flashBAC system). Construction of the pFast-Cap Vector: The synthesized Cap gene was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR)amplification using PrimeSTAR® Max DNA Polymerase (Takara, R045Q, Shiga, Japan) with specific primers (pFast-Cap-F/R). The target fragment was purified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The pFast-Dual vector was double-digested with BamHI (Takara, 1605, Shiga, Japan) and HindIII (Takara, 1615, Shiga, Japan), and the linearized vector was gel-purified. The insert and vector were ligated at a 3:1 molar ratio (insert:vector) using the ClonExpress Ultra One-Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, C115-01, Nanjing, China) and transformed into DH5α competent cells (TransGen Biotech, CD201, Beijing, China); Positive clones were selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin (Sangon Biotech, A610028, Shanghai, China) after overnight incubation at 37°C; Colony PCR and sequencing were performed for validation, and the positive recombinant plasmid was extracted using a Plasmid Extraction Kit (Tiangen, DP106, Beijing, China). Construction of the pBAC-1-Cap Vector: The same strategy was applied; The Cap gene was amplified using primers pBAC-1-Cap-F/R, and the pBAC-1 vector was digested with BamHI/HindIII for subsequent cloning. Construction of the pBAC-4×Cap Vector: A pUC19-4×Cap recombinant vector was synthesized by Shanghai Shangya Biotech; The multi-copy Cap gene fragment was obtained by double digestion with BglII (Takara, 1606, Shiga, Japan) and HindIII, then ligated into the similarly digested pBAC-1 vector using T4 DNA Ligase (NEB, M0202V) at a 5:1 insert-to-vector ratio; The ligation product was transformed into Sure competent cells (WEIDI, DL1065S, Shanghai, China). Positive clones were verified by sequencing, and the plasmid was extracted for downstream applications.

2.2. Construction of Bacmid

The Bac-to-Bac method requires the construction of bacmid by transfecting DH10Bac chemically competent cells (Weidi, DL1071, Shanghai, China) with an expression plasmid. The pFast-Cap plasmid was transformed into DH10Bac chemically competent cells, and the heat-shocked cells were plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin (Sangon Biotech, A506636, Shanghai, China), 7 μg/mL gentamicin (Sangon Biotech, A428430, Shanghai, China), 7 μg/mL tetracycline (Sangon Biotech, A430165, Shanghai, China), 40 μg/mL X-gal (Sangon Biotech, A600083, Shanghai, China), and 40 μg/mL IPTG (Sangon Biotech, A600168, Shanghai, China). Positive white colonies were selected via blue-white screening and further verified by PCR using pFast-Cap-F/R, M13(40)/Tn7R and Tn7L/M13R primers. The bacmid DNA was extracted using the BAC/PAC DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, D2156, Norcross, Georgia, USA) for subsequent baculovirus packaging.

2.3. Baculovirus Packaging and Amplification

Culture Sf9 cells in SF-SMF cell culture medium in a 27°C incubator. Ensure the cells are in the logarithmic growth phase (density approximately 1-2×106 cells/mL). Seed 2.5×106 cells in a 6-well plate with a culture volume of 2 mL. After 1 hour, replace the medium with 2.5 mL of Transfection Media (Oxford Expression Technologies, 500312, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK). For the Bac-to-Bac system, add 8 μg of Bacmid to 100 μL of Transfection Media, followed by 1.2 μL of BaculoFECTIN II (Oxford Expression Technologies, 300105, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK). For the flashBAC system, add 100 ng of flashBAC GOLD baculovirus DNA (Oxford Expression Technologies, 100202, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK) and 500 ng of pBAC-1-Cap/pBAC4×-1-Cap to 100 μL of Transfection Media, followed by 1.2 μL of BaculoFECTIN II (Oxford Expression Technologies, 300105, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK). Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 15 minutes before adding it to the 6-well plate. After 5 days, collect the cell supernatant to obtain the P1 generation of virus and store it at -80°C. To obtain the P2 generation of virus, inoculate Sf9 cells at a density of 2×106 cells/mL with multiplicity of infection (MOI)=0.05 of the P1 baculovirus stock. Collect the cell supernatant when the cell viability reaches 50%. The P3 generation of virus is obtained using the same method as for the P2 generation.

2.4. Identification and Titer Test of Baculoviruses

The second-generation (P2) baculovirus DNA was extracted using a viral genome DNA/RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, DP315, Beijing, China). PCR amplification was performed using baculovirus VP80-specific primers, and the target band was detected by agarose gel electrophoresis. Viral titer was determined using a GP64-specific antibody against baculovirus. Sf9 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 7 × 106 cells diluted in 10 mL of medium, with 100 μL of the cell suspension added to each well. After incubation at 27°C for 30 minutes, the viral stock was serially diluted in 10-fold increments across 10 gradients. Each dilution was added to a column of 8 wells in the 96-well plate, with the last two columns left as blanks. The plate was incubated at 27°C for 4 days. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS. The cells were then incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of GP64 antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-65499, CA, USA) at 37°C for 2 hours, followed by three washes. A 1:2000 dilution of anti-mouse IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488 (Thermo, A-11001, MA, USA) was added and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours, followed by another three washes. Positive wells were observed under a fluorescence microscope, and the viral titer (TCID50/mL) was calculated using the Reed & Muench method.

2.5. The Expression of Cap Protein Was Detected by SDS-PAGE and ELISA

The protein sample was treated with protein loading buffer (TransGen Biotech, DL101-02, Beijing, China) at 95°C for 5 minutes. The treated sample was then loaded onto a 12% SDS-PAGE gel (Yamei, PG113, Shanghai, China), and electrophoresis was performed at 80V for 30 minutes, followed by 120V for 1 hour and 20 minutes. Protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. The concentration of the protein sample was measured using the Quantitative Determination for the Total Concentration of PCV2-Cap Protein ELISA Kit (Womei, FGPC292002, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China), with the specific methodology detailed in the manufacturer’s instructions.

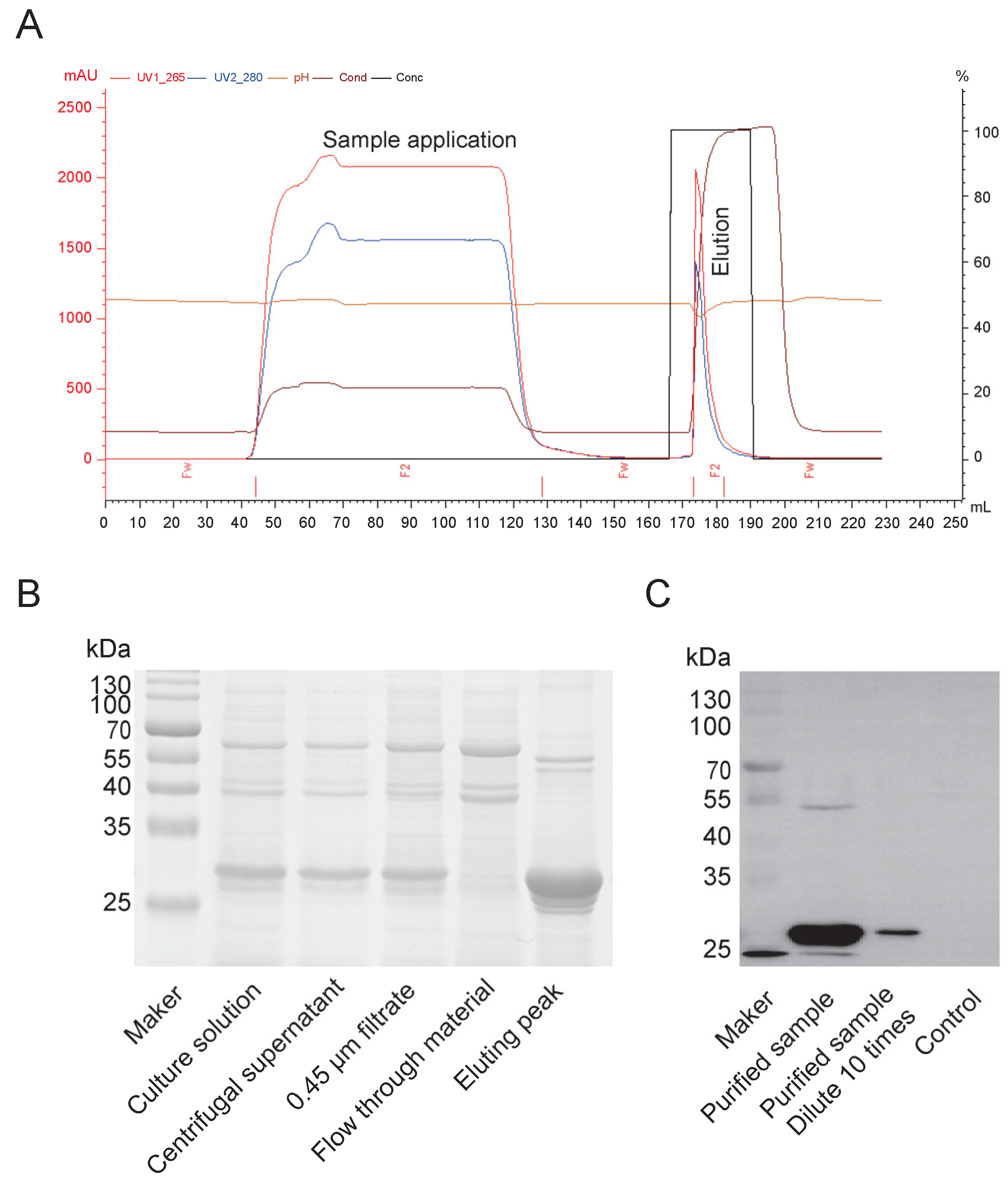

2.6. Purification and Identification of Cap Protein

Purification of Cap protein, based on its properties, primarily employs cation exchange chromatography. A chromatography column was packed with SP Sepharose Fast Flow cation exchange resin (Bestchrom, AI0011, Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China) and equilibrated with 5 column volumes (CV) of equilibration buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.0) until the pH and conductivity of the effluent stabilized. The insect cell culture supernatant was centrifuged (12,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane (Millipore, SLHP033N, Burlington, MA, USA). The sample was then diluted with equilibration buffer to achieve a conductivity below 5 mS/cm, and the pH was adjusted to 6.0. The processed sample was loaded onto the equilibrated cation exchange column at a flow rate of 1 mL/min to ensure efficient binding of the target protein. The column was washed with 10 CV of equilibration buffer to remove unbound impurities until the UV absorbance (280 nm) returned to baseline. A linear gradient elution was performed using equilibration buffer containing 1 M NaCl (Sangon Biotech, A610476, Shanghai, China) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The eluted peaks were collected while monitoring UV absorbance (280 nm). The fractions corresponding to the elution peak were pooled and analyzed for target protein purity using SDS-PAGE and Western blot. For Western blotting, proteins from an unstained PAGE gel were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Biorad, 1620177, CA, USA) using a wet transfer system. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk (Oxoid, LP0031B, MA, USA) in PBS for 2 hours, incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:1000 dilution of primary antibody against PCV2 (Bioss, bs-10057R, Beijing, China) in PBS, washed five times with PBS-Tween, incubated with a 1:5000 dilution of anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Thermo, 31460, MA, USA) at 37°C for 2 hours, washed five times with PBS-Tween, and finally developed with ECL substrate (Vazyme, E423-01/02, Shanghai, China) before imaging with a gel imaging system.

2.7. Animal Immunity and Efficacy Evaluation

Evaluate the immunogenicity of the Cap protein in mice and pigs. Six-week-old BALB/c mice (Sipeifu, Beijing, China) were randomly divided into two groups, with 5 mice in each group. The vaccine group was immunized with 50 μg of Cap protein mixed 1:1 with a water-based adjuvant, while the control group was immunized with PBS mixed 1:1 with the same adjuvant. Blood was collected from the mice 5 weeks post-immunization, and the antibody titers in the serum were determined. Healthy weaned piglets aged 2 weeks were randomly divided into two groups, with 10 piglets in each group. The vaccine group was immunized with 100 μg of Cap protein mixed 1:1 with a water-based adjuvant, while the control group was immunized with PBS mixed 1:1 with the same volume of adjuvant. Blood was collected from the piglets 5 weeks post-immunization, and the antibody titers in the serum were determined. Serum samples were collected at weeks 0 (pre-immunization), 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, and 19 post-immunization, and the antibody titers were measured. The antibody titers in piglet serum were determined by indirect ELISA (INGENASA, 11.PCV.K.1/5, Madrid, Spain) to detect Cap protein-specific antibodies. A sample was considered positive if the OD450 nm value was ≥0.5 and at least 2.1 times higher than the negative control. The antibody titers in mouse serum were measured by indirect ELISA (INGENASA, 11.PCV.K.1/5, Madrid, Spain), with the secondary antibody replaced by an HRP-labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody (Thermo, G-21040, MA, USA).

4. Discussion

PCV2 infection causes PCVD, a global immunosuppressive disease in pigs. Its clinical manifestations include PMWS and PDNS, which cause significant economic losses to the swine industry [

5,

6]. Vaccination remains the primary strategy for preventing PCVD [

6]. Cap, as the protective antigen of porcine circovirus, has been expressed in various protein expression systems, such as

E. coli, yeast and the insect baculovirus system [

25,

26,

27]. However, currently marketed products are exclusively expressed using the insect baculovirus system, indicating its superior suitability for protein expression. Common baculovirus construction systems include Bac-to-Bac and the homologous recombination method

flashBAC [

19,

20], yet few laboratories have compared the impact of different baculovirus construction systems on protein expression. Our results demonstrate that the baculovirus constructed using

flashBAC is more suitable for Cap protein expression than that constructed using the Bac-to-Bac system, regardless of whether Sf9 or High Five cells are employed. Furthermore, the insect cell line High Five cells are more conducive to Cap protein expression compared to Sf9 cells. Previous literature and patents report protein expression levels ranging from 50 to 150 μg/mL, with the highest patent-reported level reaching 200 μg/mL [

28]. In this study, the maximum expression level achieved was 432 μg/mL, significantly surpassing the values reported in the literature and patents.

In addition to codon optimization, increasing the gene copy number can enhance protein expression [

23,

29]. In this study, the

flashBAC system was used to construct baculoviruses carrying 1-copy and 4-copy Cap protein genes. We found that elevating the copy number could improve the expression level of the Cap protein, but not to the extent of a 4-fold increase—only a 12% enhancement compared to the 1-copy construct. This limited improvement may be due to the restricted expression capacity of insect cells or the presence of negative feedback mechanisms. Meanwhile, the baculovirus expressing 4 copies of the Cap protein reached its peak expression on the fourth day post-infection, followed by a decline on the fifth day. This reduction might be attributed to cellular negative feedback mechanisms or the onset of cell lysis, releasing intracellular proteases that degrade the protein. Although the Cap protein in this experiment was designed for intracellular expression and its levels decreased by the fifth day, harvesting at this time point was deemed more suitable for industrial-scale downstream purification. This is because a higher proportion of cell death at this stage facilitates the subsequent purification process.

In addition to codon optimization, increasing the gene copy number can enhance protein expression [

30]. In this study, the

flashBAC system was used to construct baculoviruses carrying 1-copy and 4-copy genes of the Cap protein. We found that elevating the copy number could improve the expression level of the Cap protein, but not to the extent of a 4-fold increase—only a 12% enhancement compared to the 1-copy construct. This limited improvement might be attributed to the constrained expression capacity of insect cells or the presence of negative feedback mechanisms [

31]. Furthermore, the baculovirus with 4 copies of the Cap protein reached peak expression on the 4 dpi, followed by a decline on the fifth day. This reduction could be due to cellular negative feedback mechanisms or the onset of cell lysis, releasing intracellular proteases that degrade the protein. Although the Cap protein in this study was designed for intracellular expression and its levels decreased by the fifth day, harvesting at this time point was deemed more suitable for industrial-scale downstream purification. This is because a higher proportion of cell death at this stage facilitates the subsequent purification process.

Baculoviruses also exhibit passage instability. With successive viral passages, an increasing number of defective viruses incapable of expressing the target protein are generated. These non-functional viral particles proliferate at a higher rate compared to viruses carrying the target gene. Consequently, the expression levels of the target protein progressively decline with extended passaging [

32]. Both industrial production guidelines and scientific literature therefore recommend limiting baculovirus passages to a maximum of five generations to maintain optimal protein expression. While increasing the copy number can enhance expression, it also raises the risk of homologous recombination in the viral genome. Thus, the probability of viral genome recombination increases with more passages [

33]. To ensure stable protein expression, it is advisable to restrict baculovirus passages to 4–5 generations. This limited number of passages effectively mitigates the risk of viral genome instability caused by increased copy numbers.

The optimization of the MOI in baculovirus infection is also an important factor in improving protein expression [

34]. In this experiment, the MOI was not optimized, and the recommended MOI of 0.05 from the kit was used. Future studies will consider MOI optimization to further enhance the expression level of the Cap protein. In addition to enhancing protein yield by optimizing the codon usage of the target protein to match that of insect cells [

29], promoter engineering is another frequently employed strategy to improve protein expression. Studies have shown that cis-linking the polyhedrin promoter to the p10 promoter enhances protein production, while co-expressing molecular chaperones and transcription-associated proteins such as baculovirus transactivation factors IE1 and IE0 can improve baculovirus protein expression levels [

35]. This study did not explore the optimization of promoter activity or the expression of molecular chaperones. Whether the use of tandem promoter combinations or the co-expression of molecular chaperones could further enhance protein expression warrants further investigation.