Introduction

Cognitive training is a clinically proven method for preventing dementia progression among at-risk individuals [

1,

2]. Recently, we conducted the SoUth Korean study to PrEvent cognitive impaiRment and protect BRAIN health through Multidomain interventions via facE-to-face and vidEo communication plaTforms randomized controlled trial (SUPERBRAIN-MEET RCT) and demonstrated the effectiveness of multidomain intervention in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [

3,

4].

The interventions include digital cognitive training, which uses serious games designed to enhance a multitude of cognitive functions such as attention, working memory, language and calculation, visuospatial ability, and executive functions [

3,

4]. Studies have demonstrated better results from personalized, difficulty-adaptive cognitive training than from conventional training programs [

5]. Digital cognitive training offers significant advantages over traditional pen-and-paper methods because it can continuously monitor in-game data and use it to adjust learning in real time, thereby enhancing training effectiveness.

Training content must be tailored to an individual’s abilities to optimize their learning. To ensure effective learning, developers should avoid content that may be too easy or too difficult [

6,

7]. The appropriate difficulty level for an individual can be inferred from their training performance, measured through accuracy. Therefore, if we can predict a learner’s training performance before they begin cognitive training, we can customize the content to match their optimal difficulty level and provide them with a personalized learning strategy.

We previously developed a novel method called cyclic dual latent discovery (CDLD), which predicts user–item interaction scores using the latent traits of users and items through dual deep neural networks (DNNs) in a cyclic training process [

8]. In this study, we applied CDLD to individuals with MCI to assess its ability to predict their training performance (accuracy) using data from SUPERBRAIN-MEET RCT. We expect that accurate predictions from CDLD will be a valuable tool for optimizing personalized cognitive training.

Method

Study Participants

This study used data from the SUPERBRAIN-MEET RCT intervention group (n = 130). All participants had confirmed diagnoses of MCI based on Peterson’s criteria [

9] and at least one modifiable risk factor for dementia, such as hypertension [

10] and diabetes mellitus [

11].

Study Design

SUPERBRAIN-MEET is a 24-week, multicenter, outcome assessor–blinded RCT with a two-parallel-group design (intervention and control). The intervention participants underwent a comprehensive 24-week intervention containing five components [

3,

4]: (1) monitoring and management of metabolic and vascular risk factors, (2) cognitive training, (3) physical exercise, (4) nutritional education, and (5) motivational enhancement.

To facilitate the intervention group’s cognitive training, they were provided with tablet PCs equipped with SUPERBRAIN, a digitalized cognitive training software for improving one’s attention, working memory, language/calculation, visuospatial abilities, and executive functions.

Table 1 summarizes the cognitive tasks on the platform, which were designed to target different cognitive functions through engaging and interactive content.

Figure 1 presents screenshots of the selected games, highlighting the platform’s user-friendly interface and interactive features. Further details on the participants and design can be found in the original SUPERBRAIN-MEET RCT [

3,

4].

Dataset

Throughout the 24-week clinical trial, the participants engaged in two 3-minute cognitive training sessions daily. Upon the participants’ completion of each activity, their performance data (accuracy) was recorded. Accuracy is calculated by dividing the number of correct responses by the total number of contents completed within each activity. Because individuals with higher cognitive abilities generally complete more items within 3 minutes, we adjusted the accuracy values with the number of items taken within that time.

To eliminate duplicate data resulting from participants repeating the same content multiple times, only the performance data from their first attempt were used for analysis. This resulted in a dataset containing 9,607 performance data from 130 individuals for 166 training contents. It also included the participants’ demographic information, such as age, sex, education level, and APOE ɛ4 genotype as well as information on training content, such as targeted cognitive domain, reinforcement element, type of manipulation, and number of colors used.

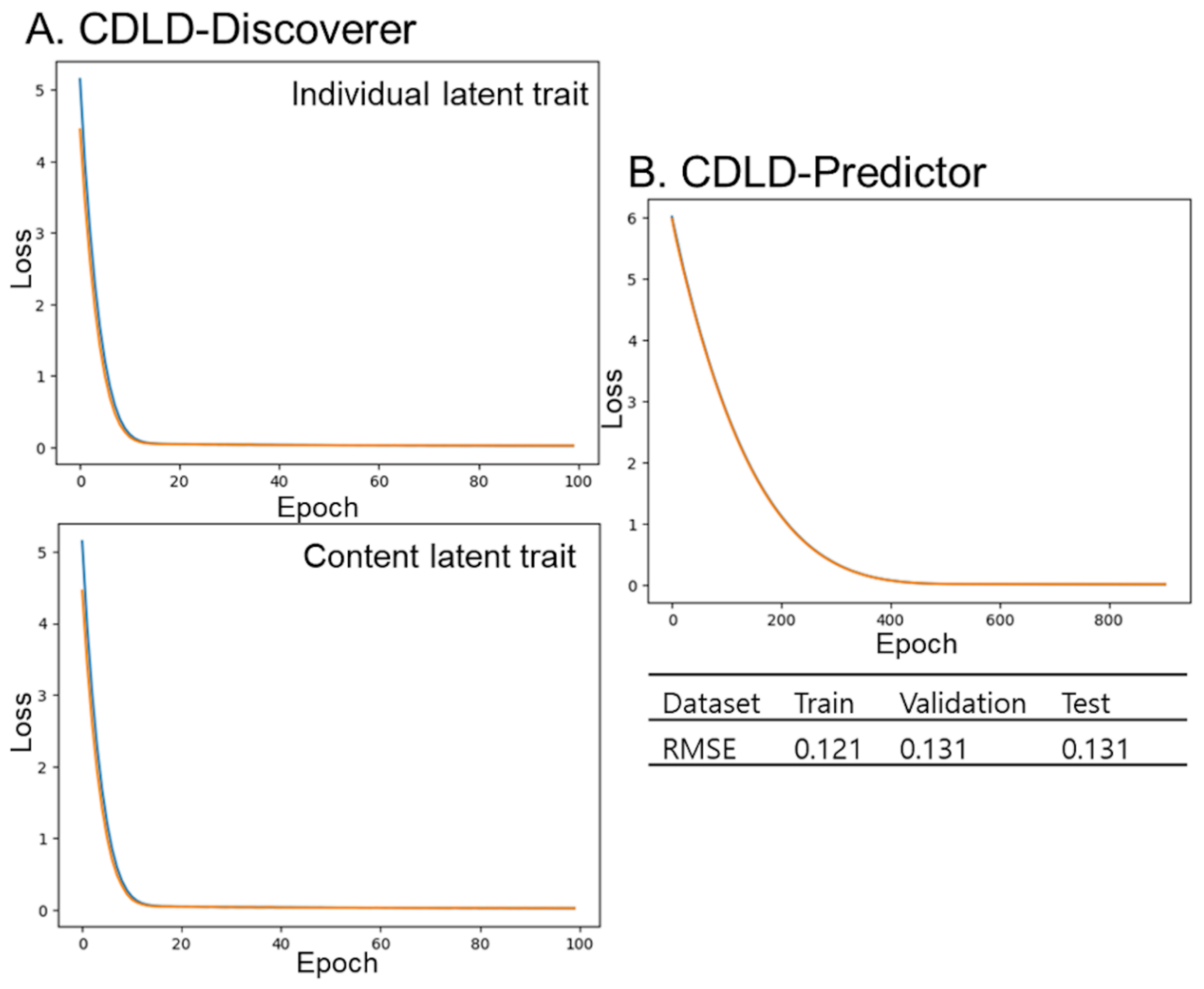

CDLD

Our previous study provides details on the CDLD model [

8], which, in sum, predicts performance on content that participants have yet to engage with. CDLD uses a cyclic training mechanism with alternating optimization to reveal the latent traits of both users and items. This study examined the performance data (accuracy) of participants engaged in cognitive training, with accuracy serving as an indirect representation of the latent traits of both participants and the training contents. CDLD is built on a dual DNN architecture consisting of CDLD-Discoverer and CDLD-Predictor networks. CDLD-Discoverer identifies latent traits using measured features and historical performance data, which are then inputted into CDLD-Predictor to predict accuracy. Individuals’ measured features were age, sex, education level, and presence of

APOE ɛ4 genotype, while contents’ measured features were targeted cognitive domain, reinforcement element, type of manipulation, and number of colors used. The model trained more than 10 epochs for each latent trait (individuals and content), and this alternating cycle was repeated for a total of 30 iterations.

Ablation Analysis

CDLD-Predictor was designed to estimate accuracy using both latent and measured traits of users and items. To determine each trait’s contribution to predictive performance, we conducted an ablation analysis in which each of the four trait types (latent and measured, for users and items) was independently shuffled before prediction, and the resulting change in RMSE was determined to assess its impact.

Latent Trait Analysis

After evaluating the role of user latent traits in the prediction of cognitive training outcomes, we examined their association with baseline cognitive performance. In the SUPERBRAIN-MEET RCT, the participants’ baseline cognitive abilities were assessed using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). We performed principal component analysis (PCA) to address the high dimensionality of the latent trait vectors (640 dimensions) and analyzed the resulting PCs using a Gaussian mixture modeling (GMM) to identify latent clusters among participants. We also determined the optimal number of clusters based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC). Finally, we conducted analysis of variance (ANOVA) to check for significant differences in baseline RBANS scores across the identified clusters.

Results

A total of 130 participants were assigned to the intervention group, and their demographic characteristics are summarized in

Table 2.

Ablation Analysis

The ablation analysis showed a substantial increase in RMSE due to the random shuffling of the latent traits of either users or items (

Table 4), suggesting these traits’ critical role in the model’s predictive accuracy.

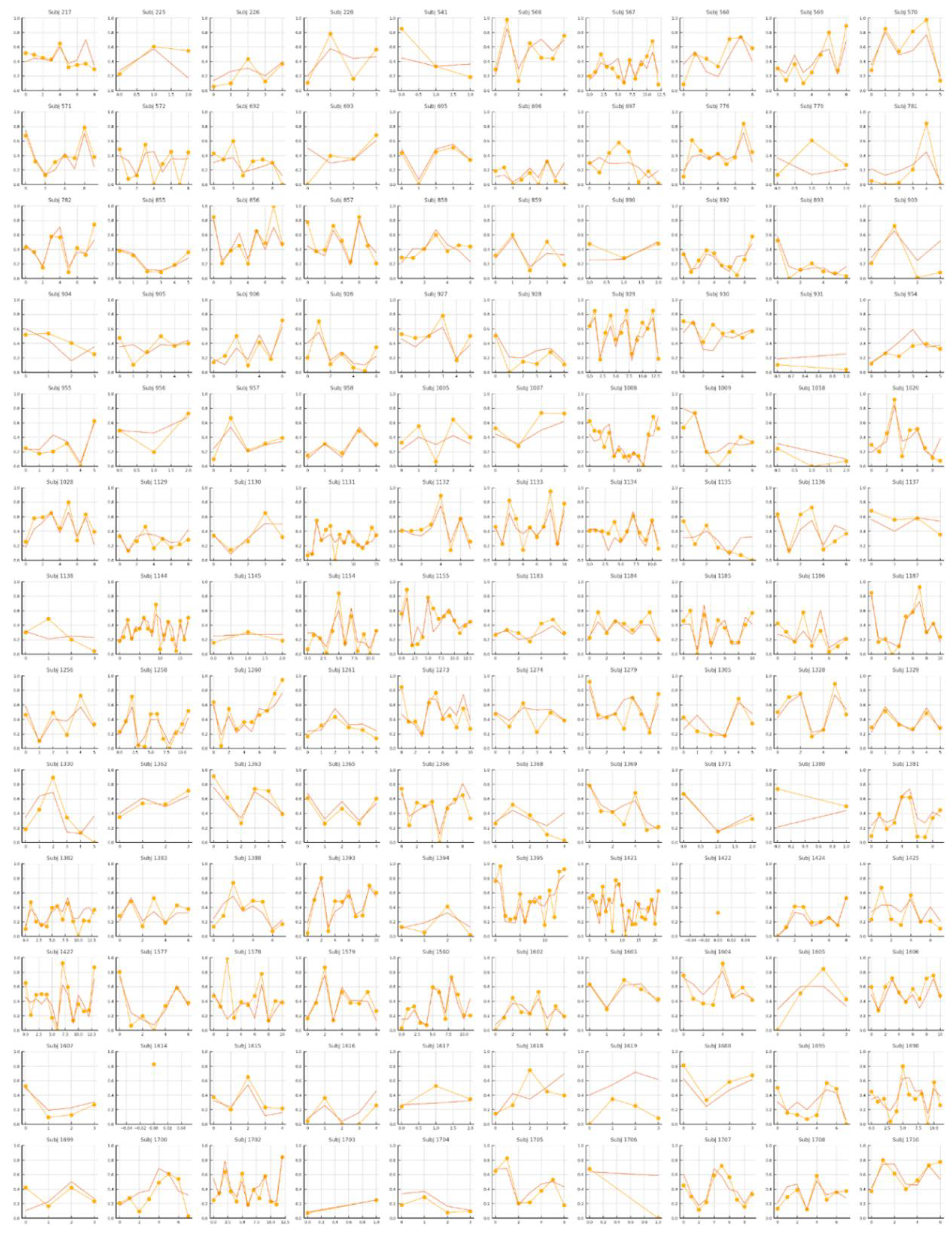

Latent Trait Analysis

Following PCA, this study retained 113 principal components (PCs) explaining 95.18% of the total variance in the latent traits for further examination. These PCs were then used as input for GMM to identify latent participant clusters. Based on the optimal AIC and BIC values, three distinct clusters were identified. Through ANOVA, marginal differences were observed in RBANS total scores across clusters (F = 2.56, P = 0.08), while two RBANS subdomains—visuospatial function (F = 4.34, P = 0.015) and immediate memory (F = 3.34, P = 0.038)—showed statistically significant differences among clusters (

Table 5).

Discussion

This study evaluated the ability of the CDLD model to estimate future cognitive training performance in individuals with MCI, with several main findings. First, CDLD provided accurate training performance predictions, outperforming traditional machine learning models. Second, ablation analysis highlighted the crucial role played by latent traits in predicting training performance. Finally, these traits were found to be associated with individuals’ baseline cognitive function, suggesting that the CDLD model can capture meaningful, individualized representations relevant to cognitive status.

The test set’s RMSE value of 0.132 indicates that CDLD captured complex patterns in user–content interactions based on both measured and latent features. The model’s superiority over traditional methods highlights the value of using latent representations in both users and items through cyclic training.

RF and GB are ensemble-based methods that use decision trees and only explicit, measured features [

13,

14]. Although effective for structured, tabular data, these methods have limited generalization ability in highly sparse settings with incomplete user–content interactions [

16,

17]. In the current dataset, each participant interacted with only a small subset of training content, thereby creating a sparse matrix. In this context, RF and GB were less effective in capturing latent behavioral patterns, increasing RMSE values.

Meanwhile, MF is a collaborative filtering approach commonly used in recommender systems to model user–item interactions by decomposing the interaction matrix into lower-dimensional latent factors [

15]. Although MF partially addresses sparsity by learning hidden representations, it operates under a linear assumption and lacks the flexibility to incorporate auxiliary features (e.g., Furthermore, it does not support the dynamic, iterative refinement of traits based on dual feature spaces [

18].

CDLD integrates the strengths of deep learning and collaborative filtering to outperform these models. Specifically, it uses a dual DNN structure that alternately learns users’ and contents’ latent traits in cyclic training [

8], allowing it to identify high-order, nonlinear patterns that tree-based or linear factorization models cannot easily capture. In addition, CDLD’s combination of latent and measured traits allows it to benefit from explicit features (e.g., age, education level, APOE status, task domain) while modeling latent cognitive characteristics inferred from user performance histories.

Ablation analysis further supports the critical role of latent traits in prediction accuracy. Shuffling user or content latent traits significantly increased the RMSE value, which indicates that these traits encode essential information that traditional features alone cannot capture. Because of CDLD’s ability to make more informed predictions about unseen user–content interactions as a result of such layered representation, it is especially well-suited for adaptive digital therapeutics.

Interestingly, the clusters obtained from user latent traits showed significant differences in individual cognitive performance, supporting the CDLD model’s ability to effectively capture latent user representations with meaningful associations with cognitive function.

This ability to predict performance before actual content engagement has substantial implications for digital cognitive training personalization. Studies have emphasized the urgency of matching task difficulty to an individual’s ability to optimize cognitive gains and engagement [

6,

7]. The present findings support the feasibility of such personalization by allowing the predictive preselection of training content tailored to an individual’s expected performance, which may help maximize the efficacy of digital cognitive interventions by minimizing frustration from demanding tasks and disengagement from excessively easy ones.

Several limitations must be considered. First, despite its superior performance, CDLD relies on a relatively complex architecture that may limit its scalability in some settings without sufficient computational infrastructure. Second, because the model was tested on only one set of data, it must be validated using other independent data. Lastly, although accuracy was the performance metric in this study, future research may benefit from incorporating additional cognitive and behavioral indicators to enrich prediction targets.

In conclusion, the present study highlights the CDLD model’s potential as a robust, data-driven approach to tailor digital cognitive training to individuals with MCI. This model’s accuracy in predicting training performance can inform the real-time customization of training content, which may enhance its effectiveness and adherence. Future studies should consider integrating these predictive algorithms into cognitive training platforms and assess their impact on long-term cognitive outcomes.

Author Contributions

H.-R.K., J.H.P., W.J., and J.M.O. conceptualized and designed the study. H.-R.K., J.H.P., W.J. and J.M.O. performed the data analysis and interpretation. W.J. drafted the manuscript. H.-R.K., J.H.P., W.J. and J.M.O. revised the manuscript. S.H.C., J.H.J., S.Y.M., Y.K.P., C.H.H., H.R.N., H.S.K. and S.H.C. contributed to the clinical data collection and patient diagnosis; they provided clinical advice throughout the study. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript’s final version.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Council of Science and Technology (NST) Aging Convergence Research Center (CRC22013-600) and Institute of Information and Communications Technology Planning and Evaluation (IITP) (2022-0-00448/RS-2022-II220448) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea, and from the Korea Dementia Research Project through the Korea Dementia Research Center (KDRC) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (RS-2021-KH112062 and RS-2021-KH112636).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the SUPERBRAIN-MEET trial. Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, the datasets are not publicly available. Access to the dataset is available from the corresponding author of SUPEPBRAIN-MEET tiral on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

H.R.K, H.J,K, and D.R. are employees of Rowan Inc. but were not involved in the original SUPERBRAIN-MEET trial; their role in the present study was limited to secondary data analysis. S.H.C., J.H.J., S.Y.M., Y.K.P., C.H.H., and H.R.N. were investigators in the original trial and are shareholders of Rowan Inc. J.H.J. and S.H.C. have served as consultants for PeopleBio Co. Ltd. C.H.H. has received research funding from Eisai Korea Inc., and S.H.C. is the head of Exercowork. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Bahar-Fuchs, A., Clare, L. & Woods, B. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for persons with mild to moderate dementia of the Alzheimer’s or vascular type: a review. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2013, 5, 35.

- Buschert, V., Bokde, A. L. W. & Hampel, H. Cognitive intervention in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 508–517.

- Cho, S. H.; et al. SoUth Korean study to PrEvent cognitive impaiRment and protect BRAIN health through Multidomain interventions via facE-to-facE and video communication plaTforms in mild cognitive impairment (SUPERBRAIN-MEET): Protocol for a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Dement. Neurocogn. Disord. 2024, 23, 30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moon, S. Y.; et al. South Korean study to prevent cognitive impairment and protect brain health through multidomain interventions via face-to-face and video communication platforms in mild cognitive impairment (SUPERBRAIN-MEET): a randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e14517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahar-Fuchs, A.; et al. Tailored and adaptive computerized cognitive training in older adults at risk for dementia: a randomized controlled trial. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 60, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R. C., Shenhav, A., Straccia, M. & Cohen, J. D. The eighty five percent rule for optimal learning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4646.

- Kidd, C., Piantadosi, S. T. & Aslin, R. N. The goldilocks effect: human infants allocate attention to visual sequences that are neither too simple nor too complex. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36399.

- Rim, D., Nuriev, S. & Hong, Y. Cyclic training of dual deep neural networks for discovering user and item latent traits in recommendation systems. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 10663–10677.

- Albert, M. S.; et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the national institute on aging-Alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Focus 2013, 11, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.; et al. 1999 World Health Organization-International Society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. Guidelines sub-committee of the World Health Organization. Clinical and experimental hypertension (New York, NY: 1993). Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 1999, 21, 1009–1060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Association, A. D. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, s5–s20. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. H. & MacKinnon, T. Artificial intelligence in fracture detection: transfer learning from deep convolutional neural networks. Clin. Radiol. 2018, 73, 439–445.

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Statist. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, Y., Bell, R. & Volinsky, C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 2009, 42, 30–37.

- Wang, X.; et al. Tem: Tree-enhanced embedding model for explainable recommendation. in Proceedings of the 2018 world wide web conference ( 2018.

- Wang, Y., He, X., Wang, H., Sun, Y. & Wang, X. Fast explainable recommendation model by combining fine-grained sentiment in review data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4940401.

- Rendle, S., Krichene, W., Zhang, L. & Anderson, J. Neural collaborative filtering vs. matrix factorization revisited in Proceedings of the 14th ACM conference on recommender systems (2020).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).