Introduction

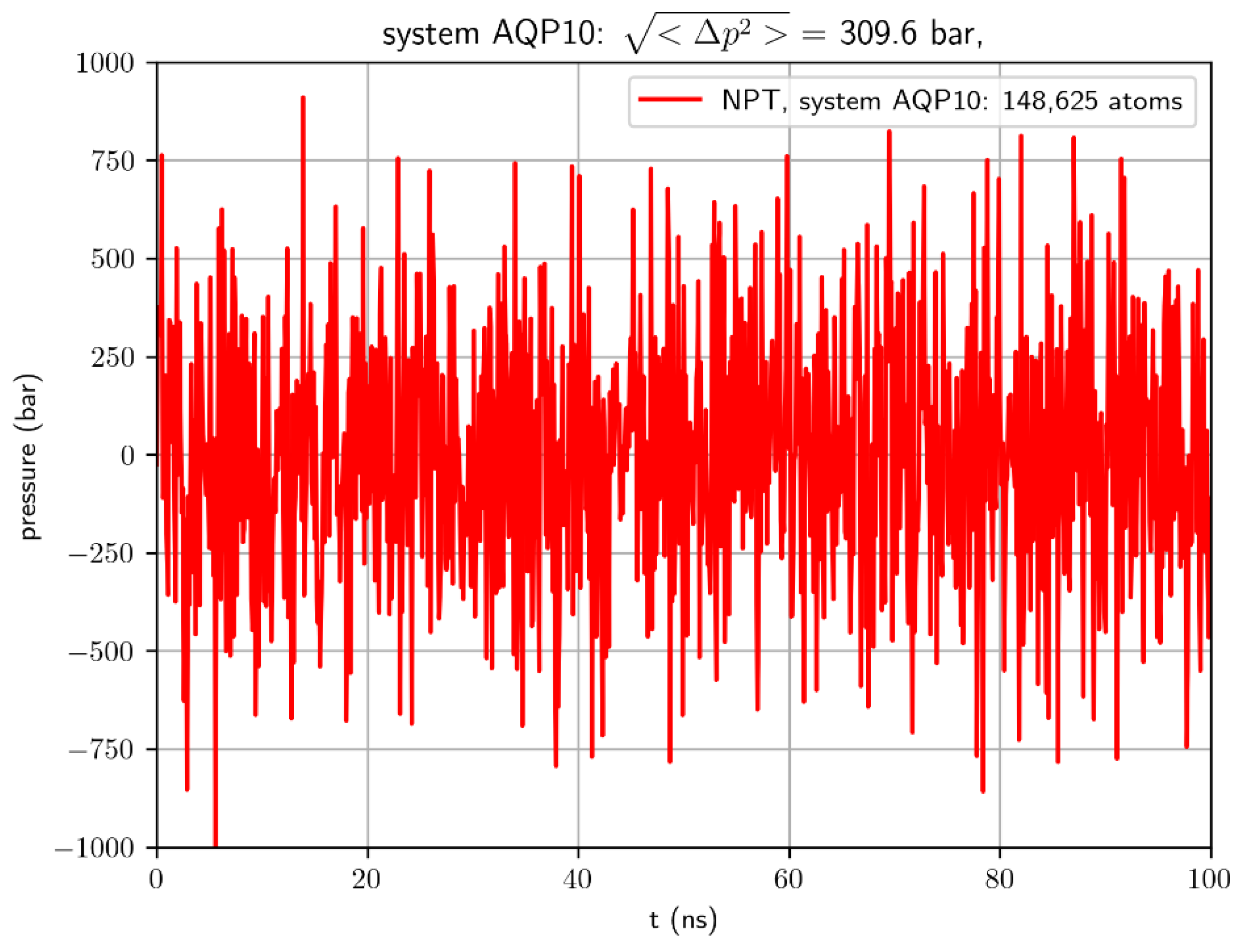

The determination of the binding affinity (or its inverse, the dissociation constant) of a protein for its substrate molecule is fundamental to the understanding of biophysical/biochemical processes. In principle, binding affinity can simply be computed from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations by counting the protein-substrate binding and unbinding events from the simulated dynamics. However, typical simulations of a system consisting of a few hundred thousand atoms are not suitable for such a simple task for the following reason: A typical model system carries fluctuations in pressure around a few hundred bars for the simulation of a constant pressure of 1 bar. See

Figure 1 for an example. Based on statistical thermodynamics[

1], this undesirable artifact is inevitable because pressure fluctuations are inversely proportional to the system size (see,

e.g., NAMD User’s Guide

https://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/namd/2.14/ug/node39.html). This huge pressure fluctuation naturally favors unbinding protein from its substrate and thus leads to the computed affinity (apparent affinity) being significantly lower than the true affinity. In another word, the computed apparent dissociation

can be significantly larger than the true dissociation constant

.

In this paper, we take a theoretical consideration of the artifactual pressure fluctuations and derive a correction factor for the computed apparent dissociation constant to estimate the true . We run four sets of MD simulations for the binding affinities of four aquaglyceroporins (AQGPs) (human AQP10, AQP3, AQP7, and E. coli GlpF) for their substrate glycerol. In each case, the apparent affinity computed from the simulation is very low (~100 mM) but the corrected estimation for the true is in the µM range. This confirms that aquaglyceroporins have reasonably high affinities for their substrate glycerol.

The significance of this study stems from the fact that aquaglyceroporins, a subfamily of aquaporin (AQP) proteins[

2,

3,

4], are responsible for facilitated diffusion of glycerol and some other small neutral solutes across the cell membrane along the concentration gradient[

5]. They are fundamental to many physiological/pathophysiological processes such as fat metabolism and metabolic diseases[

6]. This research produces insights into two controversies about whether or not an aquaglyceroporin has high affinity for its substrate glycerol and why typical simulations suggest very low aquaglyceroporin-glycerol affinity. Here is a brief summary of the current state: In functional characterization experiments in 1994[

7],

E. coli aquaglyceroporin GlpF was shown to facilitate unsaturable uptake of glycerol up to 200 mM into Xenopus oocytes, suggesting that GlpF has very low affinity for its substrate glycerol. In a series of functional experiments from 2008 to 2014[

8,

9,

10], human aquaglyceroporins AQP7, AQP9, and AQP10 were shown to conduct saturated transport of glycerol with Michaelis constants around 10 µM, indicating that human AQGPs have high affinities for glycerol. In the crystal structures available to date (GlpF in 2000[

11],

P. falciparum PfAQP in 2008[

12], AQP10 in 2018[

13], and AQP7 in 2020[

14,

15,

16]), glycerol molecules were found inside the AQGP channel and near the channel openings on both the intracellular (IC) and the extracellular (EC) sides, showing that all four AQGPs have affinities for glycerol. If we insisted that unsaturated transport precludes high affinity, these experimental data would suggest inconsistency. However, in an

in silico-in vitro study[

17] of glycerol uptake into human erythrocytes through AQP3[

18], it was shown that an AQGP (having high affinity for its substrate glycerol) can conduct glycerol transport that is unsaturated up to 400 mM. The transport pathway for unsaturated transport through a high affinity facilitator protein was shown to involve two glycerol molecules next to each other both bound inside an AQP3 channel (one at the high affinity site and one at a low affinity site) for the transport of one glycerol molecule across the cell membrane[

17]. It is the substrate-substrate interactions (mostly repulsion due to steric exclusion) inside a single-file channel that make it easy for two glycerol molecules cooperatively to move one substrate molecule across the AQGP channel

via the high affinity site. Therefore,

in vitro experiments exhibiting unsaturated glycerol transport does not preclude high affinity between an AQGP and its substrate glycerol. All

in vitro experiments either allow or show the AQGP-glycerol affinity being high. This study demonstrates why the simulations of the current literature fail to predict such high affinities and how to correct for the artifactual large fluctuations in typical MD studies.

Methods

Model System Setup and Simulation Parameters

Following the well-tested steps in the literature, we employed CHARMM-GUI[

19,

20,

21] to build an all-atom model of an AQGP tetramer embedded in a 120Å×120Å patch of membrane (lipid bilayer consisting of 193 phosphatidylethanolamine/POPE, 119 phosphatidylcholine/POPC, and 80 cholesterol/CHL1 molecules). The coordinates of AQP10 (PDB: 6F7H), AQP3, AQP7 (PDB: 6QZI), and GlpF (PDB: 1FX8) were taken from Ref. [

13], Ref. [

22], Ref. [

14] and Ref. [

11] respectively. The positioning of the AQGP tetramer was determined by matching the hydrophobic side surface with the lipid tails and aligning the channel axes perpendicular to the membrane. The AQGP-membrane complex was sandwiched between two layers of TIP3P waters, each of which was approximately 30Å thick. The system was then neutralized and salinated with Na⁺ and Cl

− ions to a salt concentration of 150 mM. Finally, glycerol was added to the system to a concentration of

. In this way, four all-atom model systems were built for the four AQGPs: System AQP10, System AQP3, System AQP7, and System GlpF.

We employed NAMD 2.13 and 3.0 [

23,

24] as the MD engines. We used CHARMM36 parameters[

25,

26,

27] for inter- and intra-molecular interactions. We followed the literature’s standard steps to equilibrate the system[

16,

28,

29,

30]. Then we ran unbiased MD for a few thousand ns with constant pressure at 1.0 bar (Nose-Hoover barostat) and constant temperature at 303.15 K (Langevin thermostat). The Langevin damping coefficient was chosen to be 1/ps. The periodic boundary conditions were applied to all three dimensions. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) was used for the long-range electrostatic interactions (grid level: 128×128×128). The time step was 2.0 fs. The cut-off for long-range interactions was set to 10 Å with a switching distance of 9 Å.

Direct Computation of Apparent Affinity from MD Simulations

We used the part of an MD trajectory when the system is fully equilibrated to compute the probability

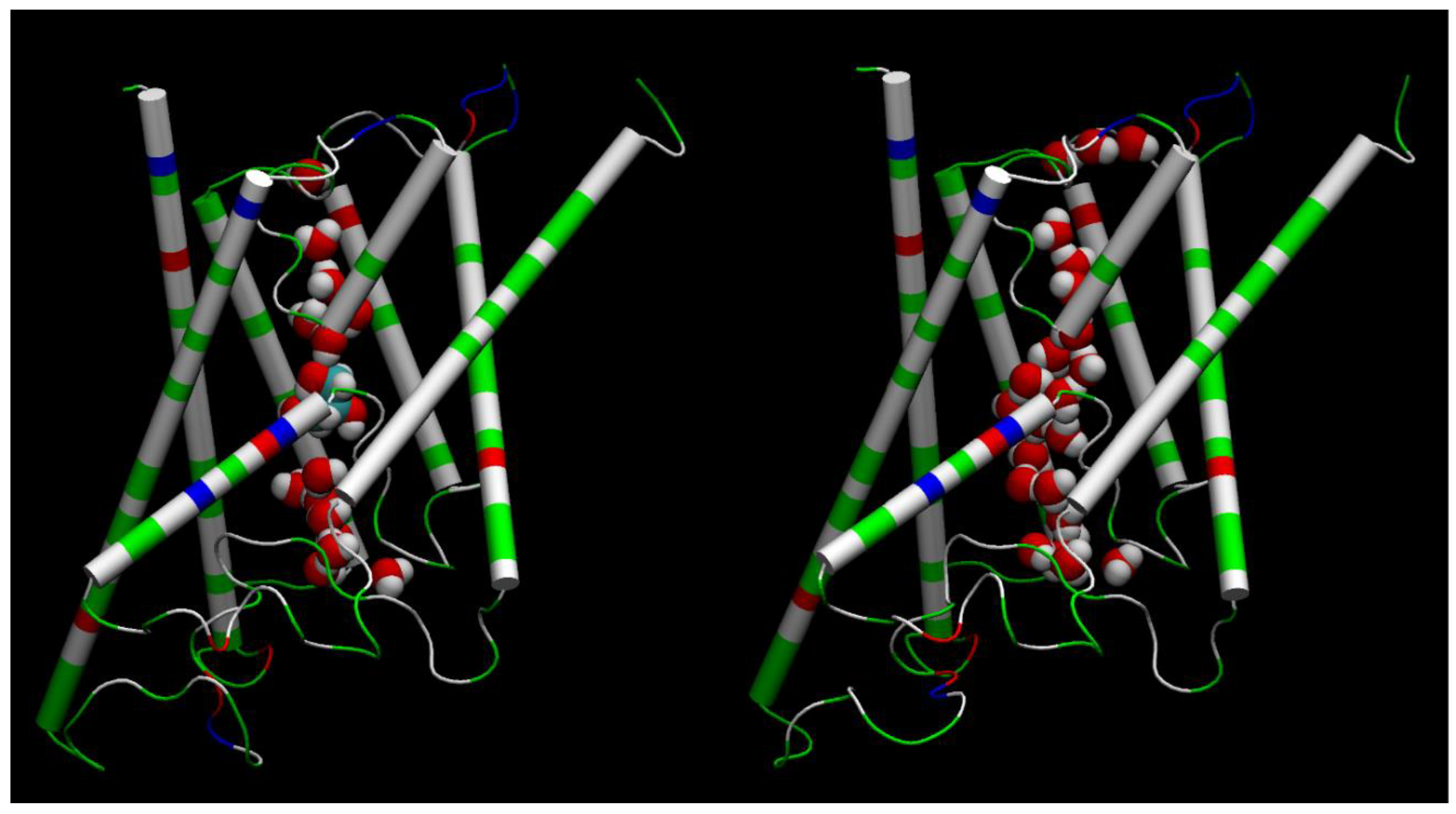

for an AQGP channel being occupied with a glycerol molecule (being inside the single-file region of the channel, 7.1 Å to the IC/EC side from the NAA/NPS motifs illustrated in

Figure 2 where a glycerol molecule is located in the left panel). Based on the equilibrium kinetics,

for a given glycerol concentration

, we computed the dissociation constant from the binding probability:

.

Theoretical Formulation of Correction for the Pressure Fluctuation

The dissociation constant of a substrate-protein complex can be computed from two partial partitions:

Here

N is the number of molecules in the system;

P, the pressure; and

T, the absolute temperature. The partial partition

is the NPT ensemble partition of the system under the condition that the substrate molecule is away from the protein, freely sampling the volume of

where

is the standard concentration of 1 mol/L. The partial partition

is the NPT ensemble partition of the system under the condition that the substrate and the protein are bound together as a complex. In this, the two partial partitions have identical dimensionalities and units. In an

in silico implementation of the NPT ensemble, the preservation of N constant is trivial and the maintenance of T constant is well accomplished with fluctuations much smaller than the temperature T but the fluctuations in P are much greater than the constant pressure of

bar in a typical MD study of the literature (See,

e.g.,

Figure 1). The root mean square of the pressure fluctuations

is much greater than the mean pressure

. (The brackets represent statistical average over P.) Therefore, the computed value, the apparent dissociation constant,

which is not equal to the true dissociation constant

Consider approximating the Gibbs free energy

as follows (

denoting the Boltzmann constant):

Here

is the mean volume of the system. Assuming the simplest form of the pressure fluctuations (with a Gaussian distribution), we have the following approximations for the partial partitions:

Therefore, we arrive at the following relationship:

Solving for

and carrying out the Gaussian averages, we obtain:

Here

and

are, respectively, the volume of system when the substrate and the protein are bound together and the volume of the system when the substrate is away from the protein. Further, we can rewrite the above equation as

It is a fundamental law of statistical thermodynamics[

31] that

where

is the bulk modulus of the system. Then, we observe that the multiplier

can be easily evaluated from

in silico simulations. This multiplier is the central result of this research, the correction factor for an accurate estimation of the true dissociation constant from simulations with large pressure fluctuations.

Considering , and the small volume difference, e.g., , leads to . Indeed, the apparent dissociation constant computed directly from MD simulations is generally very far from the true dissociation constant, depending on the volume change when a substrate molecule is dissociated from the protein.

Results

We ran 2,000 ns of MD simulation of System AQP10 (illustrated in SI,

Figure S1) after the initial runs for system preparation/setup. The RMSD curves of AQP10 tetramers (shown in SI,

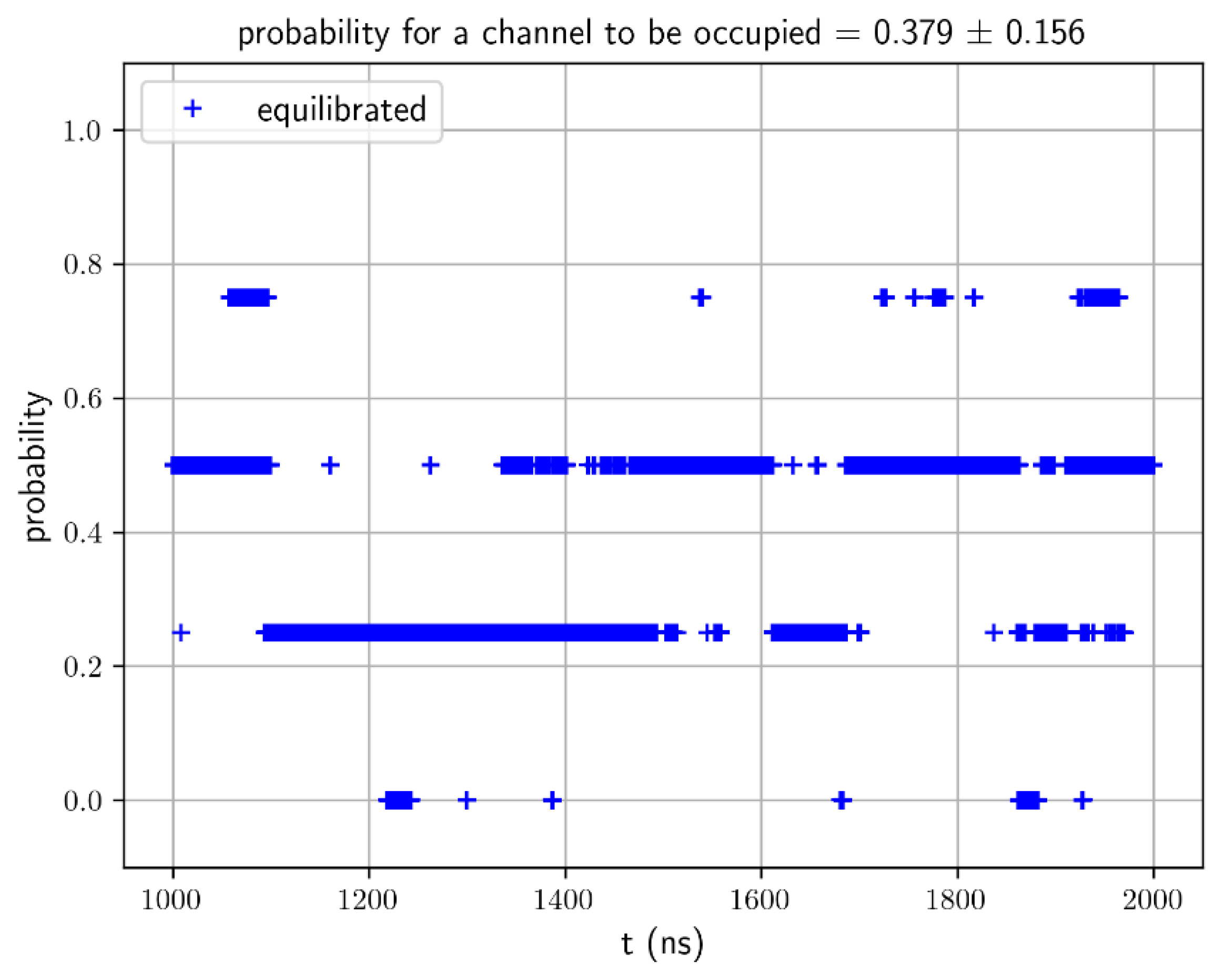

Figure S2) show that System AQP10 reached equilibrium during last 1,000 ns of the simulation. Therefore, we conducted equilibrium statistical analyses of data from this part of the MD dynamics for the estimation of glycerol-AQP10 affinity. Plotted in

Figure 3 is the probability for an AQP10 channel to be occupied by one or more glycerol molecules. This probability gives the apparent dissociation constant

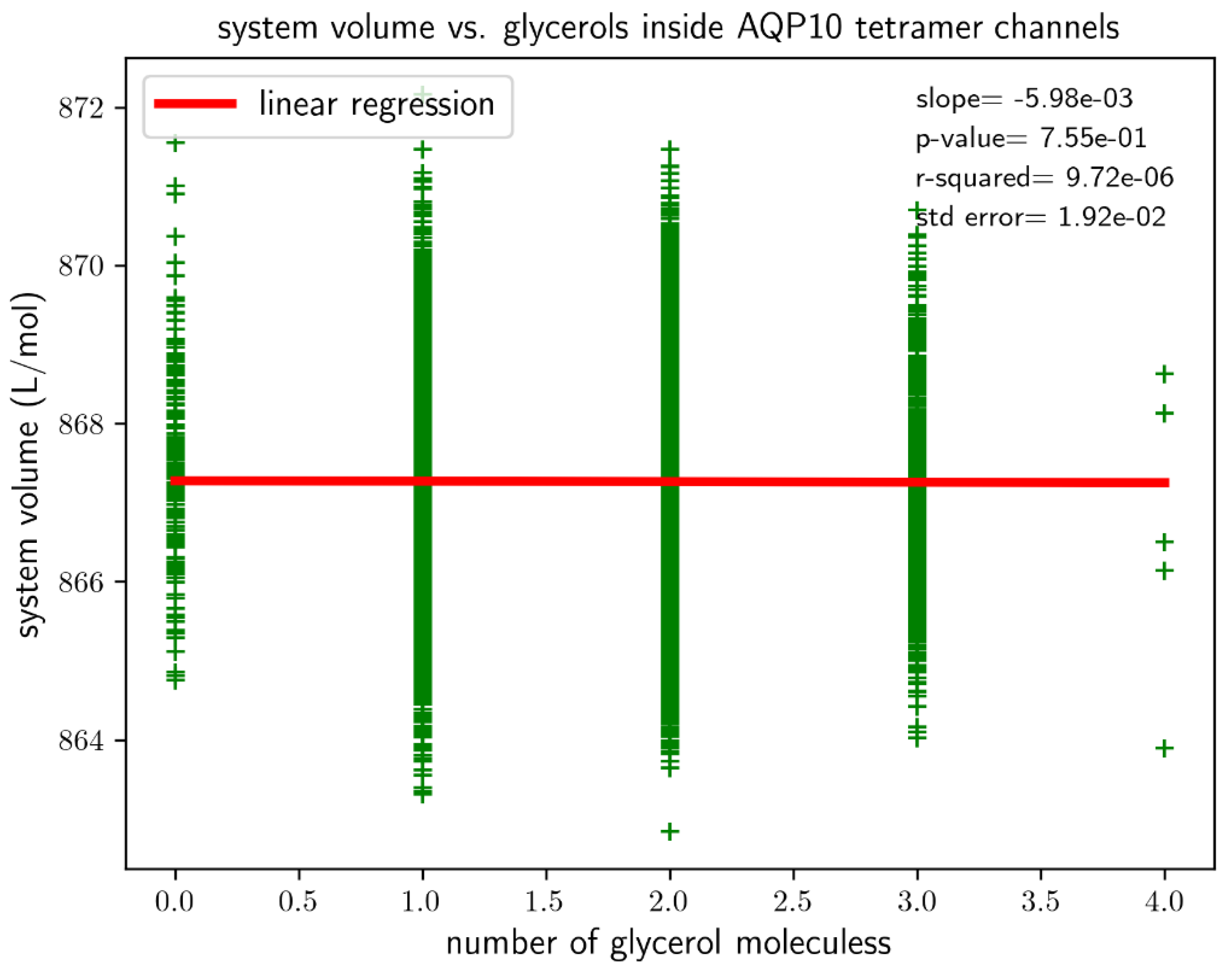

, suggesting low affinity for glycerol-AQP10 in line with the current literature. Also for the last 1,000 ns of the simulation, we analyzed the correlation between the volume of System AQP10 and number of glycerol molecules located inside the four channels of AQP10, which is shown in

Figure 4. This analysis is important because a glycerol molecule displaces different numbers of water molecules when it inside an AQP10 channel and when it is outside the protein (in the bulk of the saline). Consequently, the volume of System AQP10 fluctuates around different mean values. Linear regression of the data gives rise to the volume difference

(which is equal to the negative of the linear regression slope). Namely, the system volume averages higher by 5.98

mL/mol when a glycerol molecule is relocated from the bulk outside AQP10 to inside an AQP10 channel and, correspondingly, a number of water molecules move out of the channel to the bulk outside AQP10. The positive volume difference reflects on the fact that glycerol displaces fewer water molecules inside a channel than when it is outside the channel, which is illustrated in

Figure 2. Using this volume difference in the correction factor, we obtain the estimated true dissociation constant

, demonstrating that AQP10 has reasonably high affinity for its substrate glycerol.

In studies similar to System AQP10, we conducted 2,600 ns MD run for System AQP3, 1,500 ns MD run for System AQP7, and 1,000 ns run for System GlpF. The simulation data are shown in SI, Figs. S3 to S14. In each case, the MD was run for at least 500 ns after the system reached full equilibrium as indicated by the RMSD curves for the four monomers of an AQGP tetramer (SI,

Figure S4 for System AQP3,

Figure S8 for System AQP7, and

Figure S12 for System GlpF). The last, equilibrium parts of the trajectories (the last 600 ns for System AQP3, the last 500 ns for System AQP7, and the last 500 ns for System GlpF) were used to extract the probability for a glycerol molecule to be inside an AQGP channel (shown in SI,

Figure S5 for System AQP3,

Figure S9 for System AQP7, and

Figure S13 for System GlpF), from which the apparent dissociation constants were computed. The results are tabulated in Table I. The values of the apparent dissociation constant

all suggest very weak affinity between an AQGP and its substrate glycerol, which again, is in line with the current literature. These equilibrium parts were further analyzed for the correlations between the system volume and the number of glycerol molecules inside an AQGP tetramer, which are shown in SI,

Figure S6 for System AQP3,

Figure S10 for System AQP7, and

Figure S14 for System GlpF. Linear regression produces negative slope, giving rise to a positive volume difference

in each of the three cases (tabulated in

Table 1) and producing an estimated true

in micro molars.

Conclusions

Pressure fluctuations in a typical in silico study of the current literature can lead to predictions of very low affinities for protein-substrate binding problems. The apparent dissociation constant can be many times greater than the true dissociation constant if dissociation of the substrate from the protein corresponds to an increase in the system’s volume. The in silico studies of four aquaglyceroporins (human AQP10, AQP3, AQP7, and E. coli GlpF) all suggest low affinities without the correction factor to count for the large artifactual fluctuations in pressure. Once the correction factor is included, the estimated values of the true dissociation constant all lead to the conclusions that an aquaglyceroporin has reasonably high to very high affinity for its substrate glycerol.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Fourteen additional figures that are discussed but not included in the main text.

Author Contributions

All participated in conducting the research and editing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH (GM121275).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the computing resources provided by the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at the University of Texas at Austin.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- Landau, L.D. and E.M. Lifshitz, Statistical Physics, Part 1. 1985, Tarrytown: Pergamon Press.

- Agre, P., et al., Aquaporin water channels – from atomic structure to clinical medicine. The Journal of Physiology, 2002. 542(1): p. 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Benga, G., On the definition, nomenclature and classification of water channel proteins (aquaporins and relatives). Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 2012. 33(5–6): p. 514-517. [CrossRef]

- Agre, P., M. Bonhivers, and M.J. Borgnia, The Aquaporins, Blueprints for Cellular Plumbing Systems. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1998. 273(24): p. 14659-14662. [CrossRef]

- Engel, A. and H. Stahlberg, Aquaglyceroporins: Channel proteins with a conserved core, multiple functions, and variable surfaces, in International Review of Cytology, W.D.S. Thomas Zeuthen, Editor. 2002, Academic Press: Cambridge, MA. p. 75-104.

- Calamita, G., J. Perret, and C. Delporte, Aquaglyceroporins: Drug Targets for Metabolic Diseases? Frontiers in Physiology, 2018. 9: p. 851.

- Maurel, C., et al., Functional characterization of the Escherichia coli glycerol facilitator, GlpF, in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1994. 269(16): p. 11869-11872. [CrossRef]

- Katano, T., et al., Functional Characteristics of Aquaporin 7 as a Facilitative Glycerol Carrier. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, 2014. 29(3): p. 244-248. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M., et al., Dual Functional Characteristic of Human Aquaporin 10 for Solute Transport. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry, 2011. 27(6): p. 749-756. [CrossRef]

- Ohgusu, Y., et al., Functional Characterization of Human Aquaporin 9 as a Facilitative Glycerol Carrier. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, 2008. 23(4): p. 279-284. [CrossRef]

- Fu, D., et al., Structure of a Glycerol-Conducting Channel and the Basis for Its Selectivity. Science, 2000. 290(5491): p. 481-486. [CrossRef]

- Newby, Z.E., et al., Crystal structure of the aquaglyceroporin PfAQP from the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2008. 15(6): p. 619-25. [CrossRef]

- Gotfryd, K., et al., Human adipose glycerol flux is regulated by a pH gate in AQP10. Nature Communications, 2018. 9(1): p. 4749. [CrossRef]

- de Maré, S.W., et al., Structural Basis for Glycerol Efflux and Selectivity of Human Aquaporin 7. Structure, 2020. 28(2): p. 215-222.e3.

- Zhang, L., et al., The structural basis for glycerol permeation by human AQP7. Science Bulletin, 2021. 66(15): p. 1550-1558. [CrossRef]

- Moss, F.J., et al., Aquaporin-7: A Dynamic Aquaglyceroporin With Greater Water and Glycerol Permeability Than Its Bacterial Homolog GlpF. Frontiers in Physiology, 2020. 11: p. 728. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.A., et al., Quantitative study of unsaturated transport of glycerol through aquaglyceroporin that has high affinity for glycerol. RSC advances, 2020. 10(56): p. 34203-34214. [CrossRef]

- Roudier, N., et al., Evidence for the Presence of Aquaporin-3 in Human Red Blood Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1998. 273(14): p. 8407-8412. [CrossRef]

- Jo, S., et al., CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2008. 29(11): p. 1859-1865.

- Lee, J., et al., CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 2016. 12(1): p. 405-413. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., et al., CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder for Complex Biological Membrane Simulations with Glycolipids and Lipoglycans. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 2019. 15(1): p. 775-786.

- Rodriguez, R.A., et al., Single-channel permeability and glycerol affinity of human aquaglyceroporin AQP3. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 2019. 1861(4): p. 768-775. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.C., et al., Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2005. 26(16): p. 1781-1802. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.C., et al., Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 2020. 153(4): p. 044130. [CrossRef]

- Best, R.B., et al., Optimization of the Additive CHARMM All-Atom Protein Force Field Targeting Improved Sampling of the Backbone ϕ, ψ and Side-Chain χ1 and χ2 Dihedral Angles. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 2012. 8(9): p. 3257-3273.

- Vanommeslaeghe, K., et al., CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2010. 31(4): p. 671-690. [CrossRef]

- Klauda, J.B., et al., Update of the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2010. 114(23): p. 7830-7843. [CrossRef]

- Padhi, S. and U.D. Priyakumar, Selectivity and transport in aquaporins from molecular simulation studies. Vitam Horm, 2020. 112: p. 47-70.

- Neumann, L.S.M., A.H.S. Dias, and M.S. Skaf, Molecular Modeling of Aquaporins from Leishmania major. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2020. 124(28): p. 5825-5836. [CrossRef]

- Freites, J.A., et al., Cooperativity and allostery in aquaporin 0 regulation by Ca2+. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 2019. 1861(5): p. 988-996. [CrossRef]

- Mishin, Y., Thermodynamic theory of equilibrium fluctuations. Annals of Physics, 2015. 363: p. 48-97. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).