Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

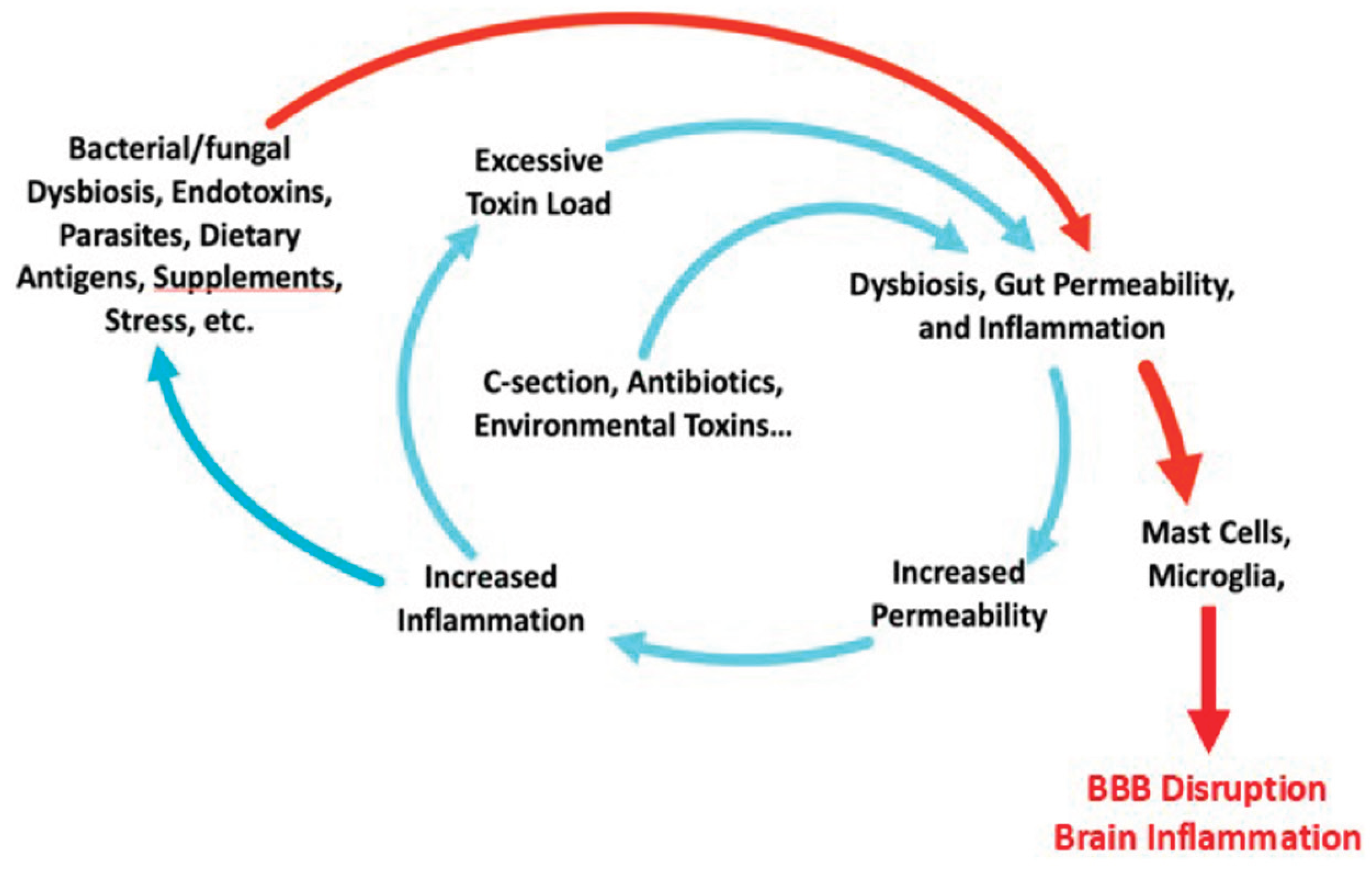

20 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

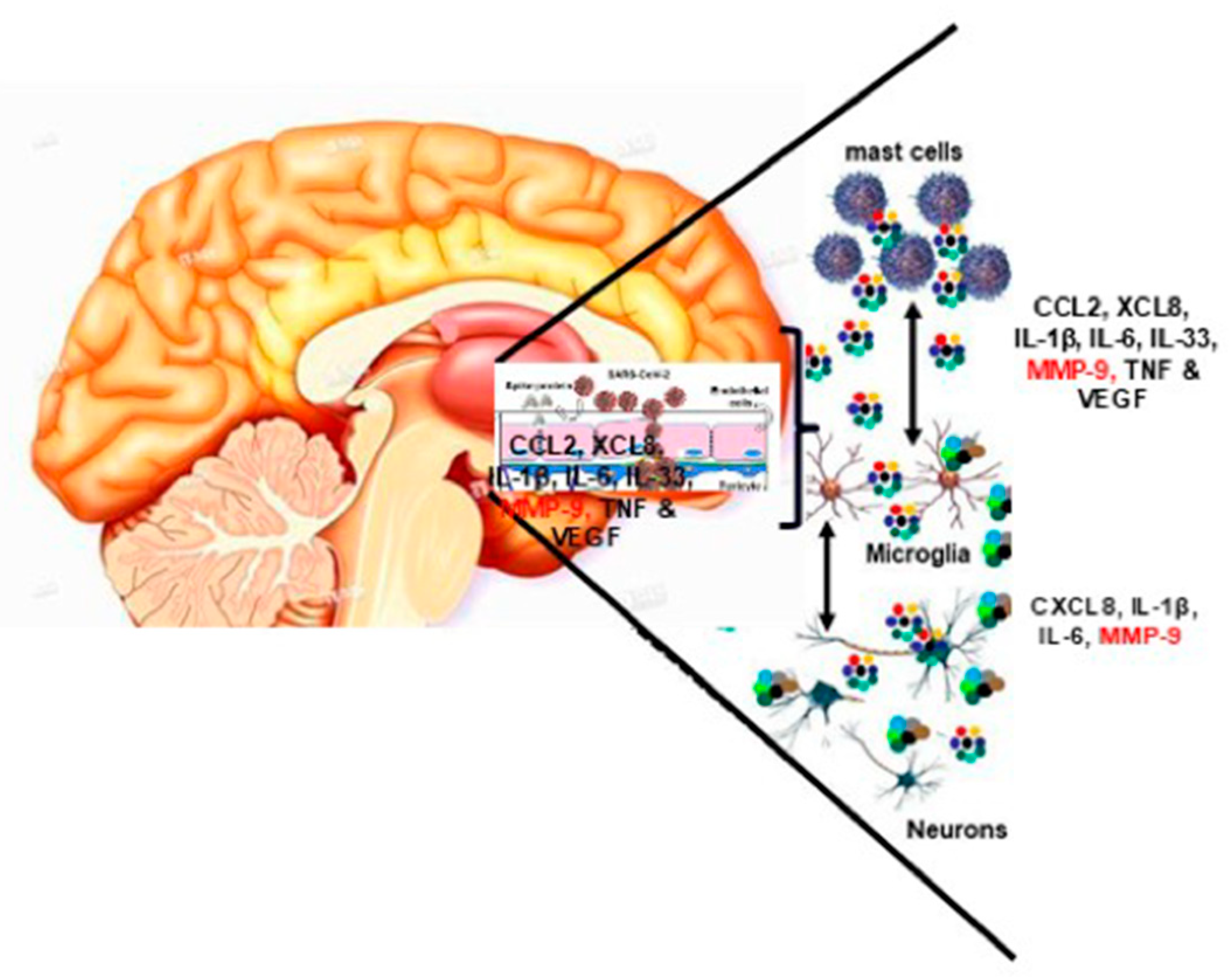

Keywords:

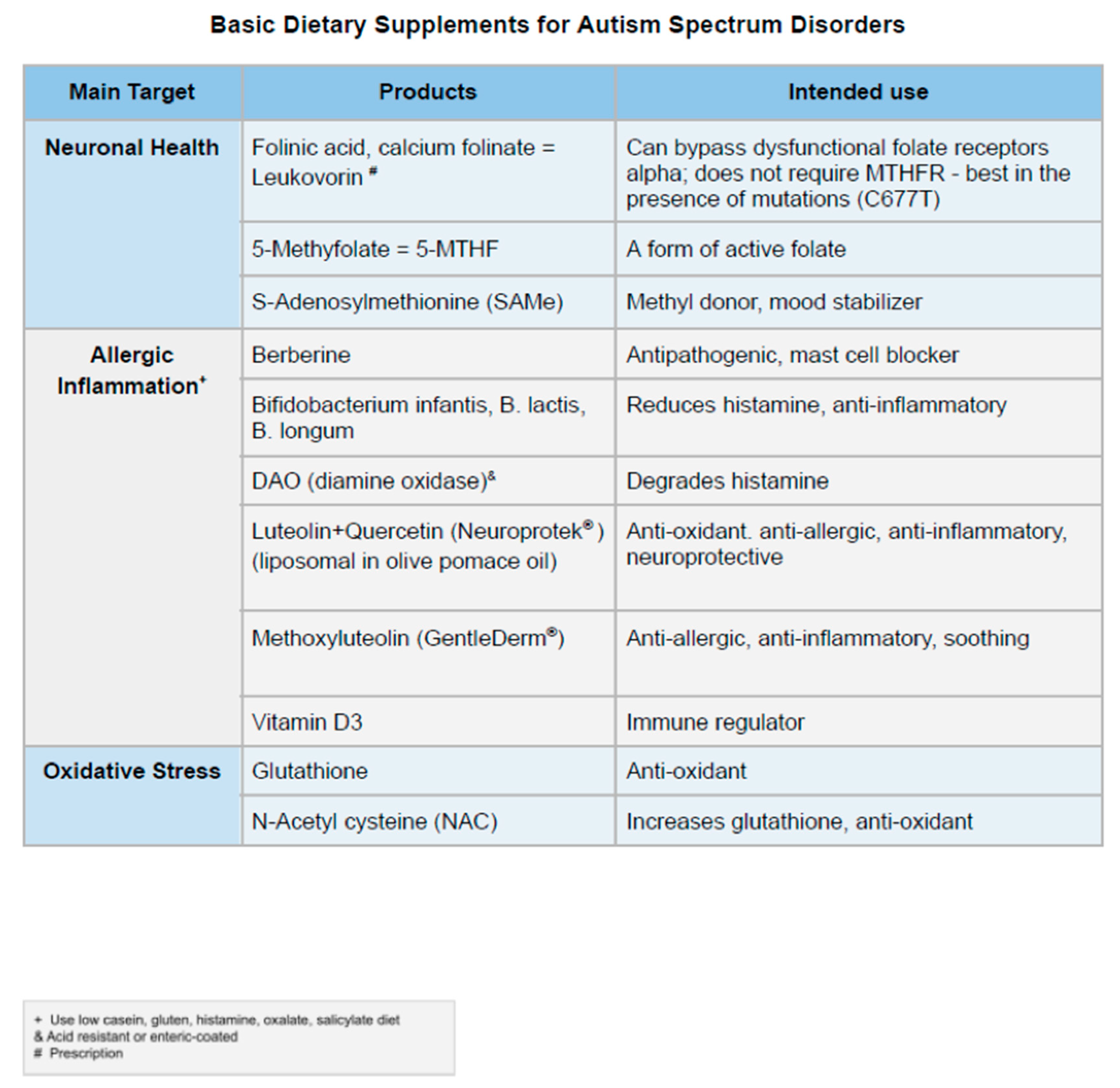

1. Introduction

2. Relevant Clinical Findings

3. How Environmental Exposures Create Chronic Gastrointestinal Inflammation and Dysfunction

4. The Role of Mast Cells in Chronic Gastrointestinal Inflammation

5. Gut Disruption and Bacterial Translocation

6. Mast Cells and ASD

7. How to Address Gut-Brain Inflammation Effectively

8. Beyond the Clinical Benefits

- (1)

- Assessing candida and the mycobiome – There are many commercially available stool kits to assess the bacterial component of the microbiome. Unfortunately, these kits lack the sensitivity to accurately detect disturbances of candida or other fungal components of the microbiome (mycobiome).

- (2)

- Assessing microglial activation – No commercially available diagnostic modalities are available to accurately assess microglial activation.

- (3)

- Assessing mast cell activity and histamine – Serum histamine has a half-life of less than two minutes and thus cannot be used to accurately detect histamine imbalances. Serum tryptase can be used to assess significant mast cell burden (e.g. systemic mastocytosis), which may limit its ability to detect more subtle forms of mast cell activation, including within the central nervous system. Urinary N-methylhistamine, Prostaglandin F2 alpha and leukotrience E4 must be collected cold in 24-hour urine and most clinical labs do not perform them.

- (4)

- Assessing endotoxemia – At this time there is no commercially available diagnostic tool available to directly assess endotoxemia.

- (5)

- Assessing total toxin load – Currently, only specialty tests are available to assess select categories of toxins. These tests are not FDA-approved and their results are at times called into question.

9. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Disclosures

References

- American Psychiatric Association 1994 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C.

- Shaw, K.A.; Williams, S.; Patrick, M.E.; Valencia-Prado, M.; Durkin, M.S.; Howerton, E.M.; Ladd-Acosta, C.M.; Pas, E.T.; Bakian, A.V.; Bartholomew, P.; Nieves-Muñoz, N.; Sidwell, K.; Alford, A.; Bilder, D.A.; DiRienzo, M.; Fitzgerald, R.T.; Furnier, S.M.; Hudson, A.E.; Pokoski, O.M.; Shea, L.; Tinker, S.C.; Warren, Z.; Zahorodny, W.; Agosto-Rosa, H.; Anbar, J.; Chavez, K.Y.; Esler, A.; Forkner, A.; Grzybowski, A.; Agib, A.H.; Hallas, L.; Lopez, M.; Magaña, S.; Nguyen, R.H.N.; Parker, J.; Pierce, K.; Protho, T.; Torres, H.; Vanegas, S.B.; Vehorn, A.; Zhang, M.; Andrews, J.; Greer, F.; Hall-Lande, J.; McArthur, D.; Mitamura, M.; Montes, A.J.; Pettygrove, S.; Shenouda, J.; Skowyra, C.; Washington, A.; Maenner, M.J. Prevalence and Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 4 and 8 Years - Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 16 sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2025, 74, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, K.; Warner, G.; Nowak, R.A.; Flaws, J.A.; Mei, W. The Impact of environmental chemicals on the gut microbiome. Toxicol Sci. 2020, 176, 253–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, D.A.; Genuis, S.J.; Frye, R.E. Environmental toxicants and autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2014, 4, e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaste, P.; Leboyer, M. Autism risk factors: genes, environment, and gene-environment interactions. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012, 14, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Wong, O.W.H.; Lu, W.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Li, M.K.T.; Liu, C.; Cheung, C.P.; Ching, J.Y.L.; Cheong, P.K.; Leung, T.F.; Chan, S.; Leung, P.; Chan, F.K.L.; Ng, S.C. Multikingdom and functional gut microbiota markers for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Microbiol. 2024, 9, 2344–2355, Erratum in: Nat Microbiol. 2025, 10, 600. doi: 10.1038/s41564-024-01900-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, P.; Chi, L.; Bodnar, W.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, B.; Bian, X.; Stewart, J.; Fry, R.; Lu, K. Gut microbiome toxicity: connecting the environment and gut microbiome-associated diseases. Toxics. 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondergaard, T.E.; Fredborg, M.; Oppenhagen Christensen, A.M.; Damsgaard, S.K.; Kramer, N.F.; Giese, H.; Sørensen, J.L. Fast screening of antibacterial compounds from fusaria. Toxins (Basel). 2016, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, W.P.; Mohd-Redzwan, S. Mycotoxin: Its impact on gut health and microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerre, P. Mycotoxin and gut microbiota interactions. Toxins (Basel). 2020, 12, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Raichon L, Venzon M, Klein J, Axelrad JE, Zhang C, Sullivan AP, Hussey GA, Casanovas-Massana A, Noval MG, Valero-Jimenez AM, Gago J, Putzel G, Pironti A, Wilder, E.; Yale IMPACTResearch, T.e.a.m.; Thorpe LE, Littman DR, Dittmann M, Stapleford KA, Shopsin B, Torres VJ, Ko AI, Iwasaki A, Cadwell K, Schluter, J. Gut microbiome dysbiosis in antibiotic-treated COVID-19 patients is associated with microbial translocation and bacteremia. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5926. [CrossRef]

- Fouladi, F.; Bailey, M.J.; Patterson, W.B.; Sioda, M.; Blakley, I.C.; Fodor, A.A.; Jones, R.B.; Chen, Z.; Kim, J.S.; Lurmann, F.; Martino, C.; Knight, R.; Gilliland, F.D.; Alderete, T.L. Air pollution exposure is associated with the gut microbiome as revealed by shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Environ Int. 2020, 138, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, E.A.; Comba, I.Y.; Cho, T.; Engen, P.A.; Yazıcı, C.; Soberanes, S.; Hamanaka, R.B.; Niğdelioğlu, R.; Meliton, A.Y.; Ghio, A.J.; Budinger, G.R.S.; Mutlu, G.M. Inhalational exposure to particulate matter air pollution alters the composition of the gut microbiome. Environ Pollut. 2018, 240, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K. Impact of delivery mode on infant gut microbiota. Ann Nutr Metab. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, A.S.; do Valle, H.A.; Vallance, B.A.; Bickford, C.; Ip, A.; Lanphear, N.; Lanphear, B.; Weikum, W.; Oberlander, T.F.; Hanley, G.E. Association between prenatal antibiotic exposure and autism spectrum disorder among term births: A population-based cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2023, 37, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zalabani, A.H.; Al-Jabree, A.H.; Zeidan, Z.A. Is cesarean section delivery associated with autism spectrum disorder? Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2019, 24, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.F.; Alessi-Severini, S.; Mahmud, S.M.; Brownell, M.; Kuo, I.F. Early childhood antibiotics use and autism spectrum disorders: a population-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Alberts, I.; Li, X. The apoptotic perspective of autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2014, 36, 13–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvez-Contreras, A.Y.; Zarate-Lopez, D.; Torres-Chavez, A.L.; Gonzalez-Perez, O. Role of oligodendrocytes and myelin in the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorder. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anashkina, A.A.; Erlykina, E.I. Molecular mechanisms of aberrant neuroplasticity in autism spectrum disorders (Review). Sovrem Tekhnologii Med. 2021, 13, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwick, G.P. Neuropsychological assessment in autism spectrum disorder and related conditions. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 19, 373–379. [CrossRef]

- White, S.W.; Oswald, D.; Ollendick, T.; Scahill, L. Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009, 29, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, S.M.; Petersen, L.; Schendel, D.E.; Mattheisen, M.; Mortensen, P.B.; Mors, O. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and autism spectrum disorders: longitudinal and offspring risk. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0141703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaser, J.; Umeano, L.; Pujari, H.P.; Nasiri, S.M.Z.; Parisapogu, A.; Shah, A.; Khan, S. Correlations between the development of social anxiety and individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023, 15, e44841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayes, S.D.; Calhoun, S.L.; Aggarwal, R.; Baker, C.; Mathapati, S.; Molitoris, S.; Mayes, R.D. Unusual fears in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013, 7, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Day, T.N.; Jones, N.; Mazefsky, C.A. Association between anger rumination and autism symptom severity, depression symptoms, aggression, and general dysregulation in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2017, 21, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. Effect of stress on neuroimmune processes. Clin Ther. 2020, 42, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiraei, P.; Bultron, G. Need for a comprehensive medical approach to the neuro-immuno-gastroenterology of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 2791–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leekam, S.R.; Nieto, C.; Libby, S.J.; Wing, L.; Gould, J. Describing the sensory abnormalities of children and adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007, 37, 894–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Cervera, P.; Pastor-Cerezuela, G.; Fernández-Andrés, M.I.; Tárraga-Mínguez, R. Sensory processing in children with autism spectrum disorder: relationship with non-verbal IQ, autism severity and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptomatology. Res Dev Disabil. 2015, 45-46, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomchek, S.D.; Dunn, W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. Am J Occup Ther. 2007, 61, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, M.A. Sensory processing in children with autism spectrum disorders and impact on functioning. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012, 59, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanner, L. Austic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943, 2, 217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nadon, G.; Feldman, D.E.; Dunn, W.; Gisel, E. Association of sensory processing and eating problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res Treat. 2011, 541926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, L.; Boudabous, J.; Khemekhem, K.; Mkawer, S.; Ayadi, H.; Moalla, Y. Feeding problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Family Medicine. 2018, 1, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madra, M.; Ringel, R.; Margolis, K.G. Gastrointestinal issues and autism spectrum disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2020, 29, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraskewich, J.; von Ranson, K.M.; McCrimmon, A.; McMorris, C.A. Feeding and eating problems in children and adolescents with autism: A scoping review. Autism. 2021, 25, 1505–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, M.J.; Ha, S.; Hwang, J.; Koyanagi, A.; Dragioti, E.; Radua, J.; Smith, L.; Jacob, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Lee, S.W.; Yon, D.K.; Thompson, T.; Cortese, S.; Lollo, G.; Liang, C.S.; Chu, C.S.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Cheon, K.A.; Shin, J.I.; Solmi, M. Association between autism spectrum disorder and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewska, J.; Klukowski, M. Gastrointestinal symptoms and autism spectrum disorder: links and risks - a possible new overlap syndrome. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2015, 6, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresnahan, M.; Hornig, M.; Schultz, A.F.; Gunnes, N.; Hirtz, D.; Lie, K.K.; Magnus, P.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Roth, C.; Schjølberg, S.; Stoltenberg, C.; Surén, P.; Susser, E.; Lipkin, W.I. Association of maternal report of infant and toddler gastrointestinal symptoms with autism: evidence from a prospective birth cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015, 72, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Magistris, L.; Familiari, V.; Pascotto, A.; Sapone, A.; Frolli, A.; Iardino, P.; Carteni, M.; De Rosa, M.; Francavilla, R.; Riegler, G.; Militerni, R.; Bravaccio, C. Alterations of the intestinal barrier in patients with autism spectrum disorders and in their first-degree relatives. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010, 51, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.T.; Jin, D.M.; Mills, R.H.; Shao, Y.; Rahman, G.; McDonald, D.; Zhu, Q.; Balaban, M.; Jiang, Y.; Cantrell, K.; Gonzalez, A.; Carmel, J.; Frankiensztajn, L.M.; Martin-Brevet, S.; Berding, K.; Needham, B.D.; Zurita, M.F.; David, M.; Averina, O.V.; Kovtun, A.S.; Noto, A.; Mussap, M.; Wang, M.; Frank, D.N.; Li, E.; Zhou, W.; Fanos, V.; Danilenko, V.N.; Wall, D.P.; Cárdenas, P.; Baldeón, M.E.; Jacquemont, S.; Koren, O.; Elliott, E.; Xavier, R.J.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Knight, R.; Gilbert, J.A.; Donovan, S.M.; Lawley, T.D.; Carpenter, B.; Bonneau, R.; Taroncher-Oldenburg, G. Multi-level analysis of the gut-brain axis shows autism spectrum disorder-associated molecular and microbial profiles. Nat Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alookaran, J.; Liu, Y.; Auchtung, T.A.; Tahanan, A.; Hessabi, M.; Asgarisabet, P.; Rahbar, M.H.; Fatheree, N.Y.; Pearson, D.A.; Mansour, R.; Van Arsdall, M.R.; Navarro, F.; Rhoads, J.M. Fungi: friend or foe? a mycobiome evaluation in children with autism and gastrointestinal symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022, 74, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Han, Y.; Dy, A.B.C.; Hagerman, R.J. The gut microbiota and autism spectrum disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson-Agramonte, M.L.A.; Noris García, E.; Fraga Guerra, J.; Vega Hurtado, Y.; Antonucci, N.; Semprún-Hernández, N.; Schultz, S.; Siniscalco, D. Immune dysregulation in autism spectrum disorder: what do we know about It? Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Tsilioni, I.; Patel, A.B.; Doyle, R. Atopic diseases and inflammation of the brain in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2016, 6, e844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Asadi, S.; Patel, A.B. Focal brain inflammation and autism. J Neuroinflammation. 2013, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwood, P.; Krakowiak, P.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Hansen, R.; Pessah, I.; Van de Water, J. Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome. Brain Behav Immun. 2011, 25, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexrode, L.E.; Hartley, J.; Showmaker, K.C.; Challagundla, L.; Vandewege, M.W.; Martin, B.E.; Blair, E.; Bollavarapu, R.; Antonyraj, R.B.; Hilton, K.; Gardiner, A.; Valeri, J.; Gisabella, B.; Garrett, M.R.; Theoharides, T.C.; Pantazopoulos, H. Molecular profiling of the hippocampus of children with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2024, 29, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Jing, J.; Liu, B.; Strathearn, L.; Bao, W. Association of food allergy and other allergic conditions with autism spectrum disorder in children. JAMA Netw Open. 2018, 1, e180279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, K. Autism spectrum disorder initiation by inflammation-facilitated neurotoxin transport. Neurochem Res. 2022, 47, 1150–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, E.; Loi, E.; Vega-Benedetti, A.F.; Carta, M.; Doneddu, G.; Fadda, R.; Zavattari, P. An overview of the main genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors involved in autism spectrum disorder focusing on synaptic activity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serkan, Y.; Beyazit, U.; Ayhan, A.B. Mycotoxin exposure and autism: a systematic review of the molecular mechanism. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesler, B.; Rappold, G.A. Emerging evidence for gene mutations driving both brain and gut dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2021, 26, 1442–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, X.; Dan, Z.; Pei, Y.; Xu, R.; Guo, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Su, C.; Zhuang, Y.; Tang, J.; Xia, Y.; Qin, L.; Hu, Z.; Liu, X. Gene variations in autism spectrum disorder are associated with alteration of gut microbiota, metabolites and cytokines. Gut Microbes. 2021, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andeweg, S.P.; Keşmir, C.; Dutilh, B.E. Quantifying the impact of human leukocyte antigen on the human gut microbiota. mSphere. 2021, 6, e0047621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Perlman, A.I.; Twahir, A.; Kempuraj, D. Mast cell activation: beyond histamine and tryptase. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2023, 19, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.N.; St John, A.L. Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010, 10, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Tsilioni, I.; Ren, H. Recent advances in our understanding of mast cell activation - or should it be mast cell mediator disorders? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019, 15, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacheva, E.; Gevezova, M.; Maes, M.; Sarafian, V. Mast cells in autism spectrum disorder-the enigma to be solved? Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boziki, M.; Theotokis, P.; Kesidou, E.; Nella, M.; Bakirtzis, C.; Karafoulidou, E.; Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou, M.; Doulberis, M.; Kazakos, E.; Deretzi, G.; Grigoriadis, N.; Kountouras, J. Impact of mast cell activation on neurodegeneration: a potential role for gut-brain axis and helicobacter pylori infection. Neurol Int. 2024, 16, 1750–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, K. The role of mast cells in allergic inflammation. Respir Med. 2012, 106, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert-Bayo, M.; Paracuellos, I.; González-Castro, A.M.; Rodríguez-Urrutia, A.; Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Alonso-Cotoner, C.; Santos, J.; Vicario, M. Intestinal mucosal mast cells: key modulators of barrier function and homeostasis. Cells. 2019, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Asadi, S.; Chen, J.; Huizinga, J.D. Irritable bowel syndrome and the elusive mast cells. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petra, A.I.; Panagiotidou, S.; Hatziagelaki, E.; Stewart, J.M.; Conti, P.; Theoharides, T.C. Gut-microbiota-brain axis and its effect on neuropsychiatric disorders with suspected immune Dysregulation. Clin Ther. 2015, 37, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoo, L.; Noti, M.; Krebs, P. Keep calm: the intestinal barrier at the interface of peace and war. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: a narrative review. Intern Emerg Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrykus, M.; Czaja-Stolc, S.; Stankiewicz, M.; Kaska, Ł.; Małgorzewicz, S. Intestinal microbiota as a contributor to chronic inflammation and its potential modifications. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, R.; Karande, A.; Ranganathan, P. Emerging role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Front Neurol. 2023, 14, 1149618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boziki, M.; Theotokis, P.; Kesidou, E.; Nella, M.; Bakirtzis, C.; Karafoulidou, E.; Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou, M.; Doulberis, M.; Kazakos, E.; Deretzi, G.; Grigoriadis, N.; Kountouras, J. Impact of mast cell activation on neurodegeneration: a potential role for gut-brain axis and helicobacter pylori infection. Neurol Int. 2024, 16, 1750–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renga, G.; Bellet, M.M.; Stincardini, C.; Pariano, M.; Oikonomou, V.; Villella, V.R.; Brancorsini, S.; Clerici, C.; Romani, L.; Costantini, C. To be or not to be a pathogen: candida albicans and celiac disease. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolinska, S.; Jutel, M.; Crameri, R.; O'Mahony, L. Histamine and gut mucosal immune regulation. Allergy. 2014, 69, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, R.A.; Tiffany, C.M.; Pakpour, N.; Lokken, K.L.; Tiffany, C.R.; Cheung, K.; Tsolis, R.M.; Luckhart, S. Mast cells and histamine alter intestinal permeability during malaria parasite infection. Immunobiology. 2016, 221, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.; Tan, Y.; Huan, R.; Guo, J.; Yang, S.; Deng, M.; Xiong, Y.; Han, G.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zha, Y.; Zhang, J. Mast cell activation mediates blood-brain barrier impairment and cognitive dysfunction in septic mice in a histamine-dependent pathway. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1090288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, A.; Akbari, P.; Garssen, J.; Fink-Gremmels, J.; Braber, S. Epithelial integrity, junctional complexes, and biomarkers associated with intestinal functions. Tissue Barriers. 2022, 10, 1996830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poto, R.; Fusco, W.; Rinninella, E.; Cintoni, M.; Kaitsas, F.; Raoul, P.; Caruso, C.; Mele, M.C.; Varricchi, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G. The role of gut microbiota and leaky gut in the pathogenesis of food allergy. Nutrients. 2023, 16, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, P.; Braber, S.; Varasteh, S.; Alizadeh, A.; Garssen, J.; Fink-Gremmels, J. The intestinal barrier as an emerging target in the toxicological assessment of mycotoxins. Arch Toxicol. 2017, 91, 1007–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiho, H.; Ihara, E.; Nakamura, K. Low-grade inflammation plays a pivotal role in gastrointestinal dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2010, 1, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K. Bacterial histamine and abdominal pain in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 19, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, M.E. An allergic basis for abdominal pain. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, S.; Maruya, M.; Kato, L.M.; Suda, W.; Atarashi, K.; Doi, Y.; Tsutsui, Y.; Qin, H.; Honda, K.; Okada, T.; Hattori, M.; Fagarasan, S. Foxp3(+) T cells regulate immunoglobulin a selection and facilitate diversification of bacterial species responsible for immune homeostasis. Immunity. 2014, 41, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.Y.; Inohara, N.; Nuñez, G. Mechanisms of inflammation-driven bacterial dysbiosis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenier, B.; Applegate, T.J. Modulation of intestinal functions following mycotoxin ingestion: meta-analysis of published experiments in animals. Toxins (Basel). 2013, 5, 396–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Palm, N.W. Immunoglobulin A and the microbiome. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2020, 56, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doron, I.; Kusakabe, T.; Iliev, I.D. Immunoglobulins at the interface of the gut mycobiota and anti-fungal immunity. Semin Immunol. 2023, 67, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Ha, S.A.; Tsuji, M.; Fagarasan, S. Intestinal IgA synthesis: a primitive form of adaptive immunity that regulates microbial communities in the gut. Semin Immunol. 2007, 19, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, S.; Maruya, M.; Kato, L.M.; Suda, W.; Atarashi, K.; Doi, Y.; Tsutsui, Y.; Qin, H.; Honda, K.; Okada, T.; Hattori, M.; Fagarasan, S. Foxp3(+) T cells regulate immunoglobulin a selection and facilitate diversification of bacterial species responsible for immune homeostasis. Immunity. 2014, 41, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, L.M.; Kawamoto, S.; Maruya, M.; Fagarasan, S. The role of the adaptive immune system in regulation of gut microbiota. Immunol Rev. 2014, 260, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhr, M.J.; Hallen-Adams, H.E. The human gut mycobiome: pitfalls and potentials--a mycologist's perspective. Mycologia. 2015, 107, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renga, G.; Moretti, S.; Oikonomou, V.; Borghi, M.; Zelante, T.; Paolicelli, G.; Costantini, C.; De Zuani, M.; Villella, V.R.; Raia, V.; Del Sordo, R.; Bartoli, A.; Baldoni, M.; Renauld, J.C.; Sidoni, A.; Garaci, E.; Maiuri, L.; Pucillo, C.; Romani, L. IL-9 and mast cells are key players of candida albicans commensalism and pathogenesis in the gut. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Peng, G.; Yue, H.; Ogawa, T.; Ikeda, S.; Okumura, K.; Ogawa, H.; Niyonsaba, F. Candidalysin, a virulence factor of candida albicans, stimulates mast cells by mediating cross-talk between signaling pathways activated by the dectin-1 receptor and MAPKs. J Clin Immunol. 2022, 42, 1009–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Q.; Luo, Y.; Scheffel, J.; Zhao, Z.; Maurer, M. The complex role of mast cells in fungal infections. Exp Dermatol. 2019, 28, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zuani, M.; Paolicelli, G.; Zelante, T.; Renga, G.; Romani, L.; Arzese, A.; Pucillo, C.E.M.; Frossi, B. Mast cells respond to candida albican infections and modulate macrophages phagocytosis of the fungus. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Aschenbrenner, D.; Yoo, J.Y.; Zuo, T. The gut mycobiome in health, disease, and clinical applications in association with the gut bacterial microbiome assembly. Lancet Microbe. 2022, 3, e969–e983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhr, M.J.; Hallen-Adams, H.E. The human gut mycobiome: pitfalls and potentials--a mycologist's perspective. Mycologia. 2015, 107, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.V.; Leonardi, I.; Iliev, I.D. Gut Mycobiota in Immunity and Inflammatory Disease. Immunity. 2019, 50, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.L.; Sokol, H. The gut mycobiota: insights into analysis, environmental interactions and role in gastrointestinal diseases. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019, 16, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, R.X.Y.; Tay, M.J.Y.; Ooi, D.S.Q.; Siah, K.T.H.; Tham, E.H.; Shek, L.P.; Meaney, M.J.; Broekman, B.F.P.; Loo, E.X.L. Understanding the link between allergy and neurodevelopmental disorders: a current review of factors and mechanisms. Front Neurol. 2021, 11, 603571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Wong, O.W.H.; Lu, W.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Li, M.K.T.; Liu, C.; Cheung, C.P.; Ching, J.Y.L.; Cheong, P.K.; Leung, T.F.; Chan, S.; Leung, P.; Chan, F.K.L.; Ng, S.C. Multikingdom and functional gut microbiota markers for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Microbiol. 2024, 9, 2344–2355, Erratum in: Nat Microbiol. 2025, 10, 600. doi: 10.1038/s41564-024-01900-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Han, Y.; Dy, A.B.C.; Hagerman, R.J. The gut microbiota and autism spectrum disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, W.P.; Mohd-Redzwan, S. mycotoxin: its impact on gut health and microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, M.J.; Ha, S.; Hwang, J.; Koyanagi, A.; Dragioti, E.; Radua, J.; Smith, L.; Jacob, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Lee, S.W.; Yon, D.K.; Thompson, T.; Cortese, S.; Lollo, G.; Liang, C.S.; Chu, C.S.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Cheon, K.A.; Shin, J.I.; Solmi, M. Association between autism spectrum disorder and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Jaber, V.R.; Pogue, A.I.; Sharfman, N.M.; Taylor, C.; Lukiw, W.J. Lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) as potent neurotoxic glycolipids in alzheimer's disease (AD). Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelli, M.; Franza, L.; Pignataro, G.; Ojetti, V.; Covino, M.; Piccioni, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Interaction between Lipopolysaccharide and Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Cammisotto, V.; Bartimoccia, S.; Pignatelli, P.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C. Gut-derived low-grade endotoxaemia, atherothrombosis and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023, 20, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuele, E.; Orsi, P.; Boso, M.; Broglia, D.; Brondino, N.; Barale, F.; di Nemi, S.U.; Politi, P. Low-grade endotoxemia in patients with severe autism. Neurosci Lett. 2010, 471, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ke, H.; Wang, S.; Mao, W.; Fu, C.; Chen, X.; Fu, Q.; Qin, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, S.; Xing, J.; Wang, M.; Deng, W. Leaky gut plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of autism in mice by activating the Llpopolysaccharide-mediated toll-like receptor 4-myeloid differentiation factor 88-nuclear factor kappa b signaling pathway. Neurosci Bull. 2023, 39, 911–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Yan, J.; Feng, D.; Ye, S.; Yang, T.; Wei, H.; Li, T.; Sun, W.; Chen, J. Critical Role of TLR4 on the microglia activation induced by maternal LPS exposure leading to ASD-like behavior of offspring. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 634837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, T.B.; Chaves-Kirsten, G.P.; Chaible, L.M.; Silva, A.C.; Martins, D.O.; Britto, L.R.; Dagli, M.L.; Torrão, A.S.; Palermo-Neto, J.; Bernardi, M.M. Hypoactivity of the central dopaminergic system and autistic-like behavior induced by a single early prenatal exposure to lipopolysaccharide. J Neurosci Res. 2012, 90, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, T.B.; Taricano, M.; Maiorka, P.C.; Palermo-Neto, J.; Bernardi, M.M. Prenatal lipopolysaccharide reduces social behavior in male offspring. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2010, 17, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, T.B.; Palermo-Neto, J.; Bernardi, M.M. A rat model of autism induced by a single early prenatal exposure to LPS. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2012, 26, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadas, M.; Wankhede, N.; Chandurkar, P.; Kotagale, N.; Umekar, M.; Katariya, R.; Waghade, A.; Kokare, D.; Taksande, B. Postnatal propionic acid exposure disrupts hippocampal agmatine homeostasis leading to social deficits and cognitive impairment in autism spectrum disorder-like phenotype in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2025, 174030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitah, K.C.; Kavaliers, M.; Ossenkopp, K.P. The enteric metabolite, propionic acid, impairs social behavior and increases anxiety in a rodent ASD model: Examining sex differences and the influence of the estrous cycle. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2023, 231, 173630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.C. The endotoxin hypothesis of neurodegeneration. J Neuroinflammation. 2019, 6, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saresella, M.; Piancone, F.; Marventano, I.; Zoppis, M.; Hernis, A.; Zanette, M.; Trabattoni, D.; Chiappedi, M.; Ghezzo, A.; Canevini, M.P.; la Rosa, F.; Esposito, S.; Clerici, M. Multiple inflammasome complexes are activated in autistic spectrum disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2016, 57, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An overview of mechanisms of activation and regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, O.; Frising, U.C.; Kucharíková, S.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A.; van Loo, G.; Van Dijck, P.; Wullaert, A. Candidalysin crucially contributes to nlrp3 inflammasome activation by candida albicans hyphae. mBio. 2019, 10, e02221–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCurdy, J.D.; Lin, T.J.; Marshall, J.S. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated activation of murine mast cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2001, 70, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Song, X.T.; Liu, B.; Luan, T.T.; Liao, S.L.; Zhao, Z.T. The emerging role of mast cells in response to fungal infection. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 688659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Hammock, E.A.D. Oxytocin and microglia in the development of social behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2022, 377, 20210059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Rund, L.; Vailati-Riboni, M.; Matt, S.; Soto-Diaz, K.; Beever, J.; Allen, J.M.; Woods, J.A.; Steelman, A.J.; Johnson, R.W. The emergence of inflammatory microglia during gut inflammation is not affected by FFAR2 expression in intestinal epithelial cells or peripheral myeloid cells. Brain Behav Immun. 2024, 118, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Haq, R.; Schlachetzki, J.C.M.; Glass, C.K.; Mazmanian, S.K. Microbiome-microglia connections via the gut-brain axis. J Exp Med. 2019, 216, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Li, G.; Qian, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, B.; Hong, J.S.; Block, M.L. Interactive role of the toll-like receptor 4 and reactive oxygen species in LPS-induced microglia activation. Glia. 2005, 52, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Jalabi, W.; Shpargel, K.B.; Farabaugh, K.T.; Dutta, R.; Yin, X.; Kidd, G.J.; Bergmann, C.C.; Stohlman, S.A.; Trapp, B.D. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and neuroprotection against experimental brain injury is independent of hematogenous TLR4. J Neurosci. 2012, 32, 11706–11715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Zhu, M.; Che, X.; Wang, H.; Liang, X.J.; Wu, C.; Xue, X.; Yang, J. Lipopolysaccharide induces neuroinflammation in microglia by activating the MTOR pathway and downregulating Vps34 to inhibit autophagosome formation. J Neuroinflammation. 2020, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Lee, D.; You, H.; Lee, M.; Kim, H.; Cheong, E.; Um, J.W. LPS induces microglial activation and GABAergic synaptic deficits in the hippocampus accompanied by prolonged cognitive impairment. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 6547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozal, E.; Jagadapillai, R.; Cai, J.; Barnes, G.N. Potential crosstalk between sonic hedgehog-WNT signaling and neurovascular molecules: Implications for blood-brain barrier integrity in autism spectrum disorder. J Neurochem. 2021, 159, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Alberts, I.; Li, X. The apoptotic perspective of autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2014, 36, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, D.J.; Choi, H.B.; Hines, R.M.; Phillips, A.G.; MacVicar, B.A. Prevention of LPS-induced microglia activation, cytokine production and sickness behavior with TLR4 receptor interfering peptides. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e60388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, G.S.; Kanashiro, A.; Santin, F.M.; de Souza, G.E.; Nobre, M.J.; Coimbra, N.C. Lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behaviour evaluated in different models of anxiety and innate fear in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012, 110, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesmans, S.; Meert, T.F.; Bouwknecht, J.A.; Acton, P.D.; Davoodi, N.; De Haes, P.; Kuijlaars, J.; Langlois, X.; Matthews, L.J.; Ver Donck, L.; Hellings, N.; Nuydens, R. Systemic immune activation leads to neuroinflammation and sickness behavior in mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 271359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onore, C.; Careaga, M.; Ashwood, P. The role of immune dysfunction in the pathophysiology of autism. Brain Behav Immun. 2012, 26, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, M.; Hüwel, S.; Galla, H.J.; Humpf, H.U. Blood-Brain Barrier Effects of the Fusarium Mycotoxins Deoxynivalenol, 3 Acetyldeoxynivalenol, and moniliformin and their transfer to the brain. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0143640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Hossain, M.A.; German, N.; Al-Ahmad, A.J. Gliotoxin penetrates and impairs the integrity of the human blood-brain barrier in vitro. Mycotoxin Res. 2018, 34, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, K.; Uetsuka, K. Mechanisms of mycotoxin-induced neurotoxicity through oxidative stress-associated pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2011, 12, 5213–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, N.J. Inflammatory mediators and modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000, 20, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Song, R.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X. Effects of ultra-processed foods on the microbiota-gut-brain axis: The bread-and-butter issue. Food Res Int. 2023, 167, 112730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Konstantinidou, A.D. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and the blood-brain-barrier. Front Biosci. 2007, 12, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Chandler, N.; Kandere, K.; Basu, S.; Jacobson, S.; Connolly, R.; Tutor, D.; Theoharides, T.C. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and brain mast cells regulate blood-brain-barrier permeability induced by acute stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002, 303, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. Mast cells: the immune gate to the brain. Life Sci. 1990, 46, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, D.P.; Lehrman, E.K.; Kautzman, A.G.; Koyama, R.; Mardinly, A.R.; Yamasaki, R.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Greenberg, M.E.; Barres, B.A.; Stevens, B. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012, 74, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Hammock, E.A.D. Oxytocin and microglia in the development of social behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2022, 377, 20210059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. Microglia and astrocytes underlie neuroinflammation and synaptic susceptibility in autism spectrum disorder. Front Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1125428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, N.B.; Munro, D.A.D.; Bestard-Cuche, N.; Uyeda, A.; Bogie, J.F.J.; Hoffmann, A.; Holloway, R.K.; Molina-Gonzalez, I.; Askew, K.E.; Mitchell, S.; Mungall, W.; Dodds, M.; Dittmayer, C.; Moss, J.; Rose, J.; Szymkowiak, S.; Amann, L.; McColl, B.W.; Prinz, M.; Spires-Jones, T.L.; Stenzel, W.; Horsburgh, K.; Hendriks, J.J.A.; Pridans, C.; Muramatsu, R.; Williams, A.; Priller, J.; Miron, V.E. Microglia regulate central nervous system myelin growth and integrity. Nature. 2023, 613, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Liu, C.; Deng, S.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, G.Y.; Tian, H.; Tang, Y. The roles of microglia and astrocytes in myelin phagocytosis in the central nervous system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2023, 43, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Teva, J.L.; Cuadros, M.A.; Martín-Oliva, D.; Navascués, J. Microglia and neuronal cell death. Neuron Glia Biol. 2011, 7, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, T.L.; Béchade, C.; D'Andrea, I.; St-Pierre, M.K.; Henry, M.S.; Roumier, A.; Tremblay, M.E. Microglia gone rogue: impacts on lsychiatric disorders across the lifespan. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.I.; Kern, J.K. Evidence of microglial activation in autism and its possible role in brain underconnectivity. Neuron Glia Biol. 2011, 7, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ellis, S.E.; Ashar, F.N.; Moes, A.; Bader, J.S.; Zhan, J.; West, A.B.; Arking, D.E. Transcriptome analysis reveals dysregulation of innate immune response genes and neuronal activity-dependent genes in autism. Nat Commun. 2014, 5, 5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, L.R.; Williams, K.; Pittenger, C. Microglial dysregulation in psychiatric disease. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013, 608654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrelli, F.; Pucci, L.; Bezzi, P. Astrocytes and microglia and their potential link with autism spectrum disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Kavalioti, M.; Tsilioni, I. Mast cells, stress, fear and autism spectrum disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouveia, F.V.; Hamani, C.; Fonoff, E.T.; Brentani, H.; Alho, E.J.L.; de Morais, R.M.C.B.; de Souza, A.L.; Rigonatti, S.P.; Martinez, R.C.R. Amygdala and hypothalamus: historical overview with focus on aggression. Neurosurgery. 2019, 85, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melbourne, J.K.; Chandler, C.M.; Van Doorn, C.E.; Bardo, M.T.; Pauly, J.R.; Peng, H.; Nixon, K. Primed for addiction: A critical review of the role of microglia in the neurodevelopmental consequences of adolescent alcohol drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021, 45, 1908–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.C.M.; Iglesias, L.P.; Candelario-Jalil, E.; Khoshbouei, H.; Moreira, F.A.; de Oliveira, A.CP. Role of microglia in psychostimulant addiction. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, E.; Kim, Y.K. Neuroinflammation-associated alterations of the brain as potential neural biomarkers in anxiety disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. The crosstalk between the “inflamed” mind and the “impulsive” mind: activation of microglia and impulse control disorders. Second International Conference on Biological Engineering and Medical Science. 2023, 126112H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokokura, M.; Takebasashi, K.; Takao, A.; Nakaizumi, K.; Yoshikawa, E.; Futatsubashi, M.; Suzuki, K.; Nakamura, K.; Yamasue, H.; Ouchi, Y. In vivo imaging of dopamine D1 receptor and activated microglia in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a positron emission tomography study. Mol Psychiatry. 2021, 26, 4958–4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Guan, A.; Liu, J.; Peng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S. Noteworthy perspectives on microglia in neuropsychiatric disorders. J Neuroinflammation. 2023, 20, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, J.F.G.; DelPozo-Banos, M.; Frizzati, A.; Rai, D.; John, A.; Hall, J. Neurological and psychiatric disorders among autistic adults: a population healthcare record study. Psychol Med. 2023, 53, 5663–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.W.; Oswald, D.; Ollendick, T.; Scahill, L. Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009, 29, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaser, J.; Umeano, L.; Pujari, H.P.; Nasiri, S.M.Z.; Parisapogu, A.; Shah, A.; Khan, S. Correlations between the development of social anxiety and individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023, 15, e44841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayes SD, Calhoun SL, Aggarwal R, Baker C, Mathapati S, Molitoris S, Mayes RD. Unusual fears in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013, 7, 151–158. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Day, T.N.; Jones, N.; Mazefsky, C.A. Association between anger rumination and autism symptom severity, depression symptoms, aggression, and general dysregulation in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2017, 21, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Huitrón, R.; Ugalde Muñiz, P.; Pineda, B.; Pedraza-Chaverrí, J.; Ríos, C.; Pérez-de la Cruz, V. Quinolinic acid: an endogenous neurotoxin with multiple targets. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, V.; Simsek, S.; Cetin, I.; Dokuyucu, R. Kynurenine, kynurenic acid, quinolinic acid and interleukin-6 levels in the serum of patients with autism spectrum disorder. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023, 59, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthy, E.; Ellender, T. Histamine, Neuroinflammation and Neurodevelopment: A Review. Front Neurosci. 2021, 15, 680214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasselin, J.; Lekander, M.; Benson, S.; Schedlowski, M.; Engler, H. Sick for science: experimental endotoxemia as a translational tool to develop and test new therapies for inflammation-associated depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2021, 26, 3672–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. Mast cells: the immune gate to the brain. Life Sci. 1990, 46, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L.; Giusti, P. Mast cells, glia and neuroinflammation: partners in crime? Immunology. 2014, 141, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zeng, X.; Yang, H.; Hu, G.; He, S. Mast cell tryptase induces microglia activation via protease-activated receptor 2 signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012, 29, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, S. Induction of microglial activation by mediators released from mast cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016, 38, 1520–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, M.P.B.; Blixt, F.W.; Peesh, P.; Khan, R.; Korf, J.; Lee, J.; Jagadeesan, G.; Andersohn, A.; Das, T.K.; Tan, C.; Di Gesu, C.; Colpo, G.D.; Moruno-Manchón, J.F.; McCullough, L.D.; Bryan, R.; Ganesh, B.P. Stabilizing histamine release in gut mast cells mitigates peripheral and central inflammation after stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2023, 20, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Kavalioti, M.; Tsilioni, I. Mast cells, stress, fear and autism spectrum disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. The impact of psychological stress on mast cells. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 25, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Stewart, J.M.; Panagiotidou, S.; Melamed, I. Mast cells, brain inflammation and autism. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016, 778, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Doyle, R. Autism, gut-blood-brain barrier, and mast cells. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008, 28, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Zhang, B. Neuro-inflammation, blood-brain barrier, seizures and autism. J Neuroinflammation. 2011, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. Is a subtype of autism an allergy of the brain? Clin Ther. 2013, 35, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Stewart, J.M.; Panagiotidou, S.; Melamed, I. Mast cells, brain inflammation and autism. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016, 778, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Asadi, S.; Panagiotidou, S.; Weng, Z. The "missing link" in autoimmunity and autism: extracellular mitochondrial components secreted from activated live mast cells. Autoimmun Rev. 2013, 12, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritzen, K.H.; Moldestad, O.; Eide, L.; Carlsen, H.; Nesse, G.; Storm, J.F.; Mansuy, I.M.; Bergersen, L.H.; Klungland, A. Mitochondrial DNA toxicity in forebrain neurons causes apoptosis, neurodegeneration, and impaired behavior. Mol Cell Biol. 2010, 30, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.G.; Waton, N.G. Absorption of histamine from the gastrointestinal tract of dogs in vivo. J Physiol. 1968, 198, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scammell, T.E.; Jackson, A.C.; Franks, N.P.; Wisden, W.; Dauvilliers, Y. Histamine: neural circuits and new medications. Sleep. 2019, 42, zsy183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sha, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Dong, H.; Qian, Y. The Mast Cell Is an Early Activator of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier dysfunction in the jippocampus. Mediators Inflamm. 2020, 8098439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, H.L.; Sergeeva, O.A.; Selbach, O. Histamine in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2008, 88, 1183–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devnani, P.A.; Hegde, A.U. Autism and sleep disorders. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2015, 10, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Suga, N. Histaminergic modulation of nonspecific plasticity of the auditory system and differential gating. J Neurophysiol. 2013, 109, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, R.; Seyfarth, E.A. Acetylcholine and histamine are transmitter candidates in identifiable mechanosensitive neurons of the spider Cupiennius salei: an immunocytochemical study. Cell Tissue Res. 1997, 287, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orona, E.; Ache, B.W. Physiological and pharmacological evidence for histamine as a neurotransmitter in the olfactory CNS of the spiny lobster. Brain Res. 1992, 590, (1–2), 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saure, E.; Lepistö-Paisley, T.; Raevuori, A.; Laasonen, M. Atypical sensory processing is associated with lower body mass index and increased aating disturbance in individuals with anorexia nervosa. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13, 850594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojovic, N.; Ben Hadid, L.; Franchini, M.; Schaer, M. Sensory processing issues and their association with social difficulties in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Med. 2019, 8, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, M.J.; Ha, S.; Hwang, J.; Koyanagi, A.; Dragioti, E.; Radua, J.; Smith, L.; Jacob, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Lee, S.W.; Yon, D.K.; Thompson, T.; Cortese, S.; Lollo, G.; Liang, C.S.; Chu, C.S.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Cheon, K.A.; Shin, J.I.; Solmi, M. Association between autism spectrum disorder and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W. Dietary Fiber Intake and Gut Microbiota in Human Health. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Dollive, S.; Grunberg, S.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Wu, G.D.; Lewis, J.D.; Bushman, F.D. Archaea and fungi of the human gut microbiome: correlations with diet and bacterial residents. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e66019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlanson-Albertsson, C.; Stenkula, K.G. The importance of food for endotoxemia and an inflammatory response. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochum, C. Histamine intolerance: symptoms, diagnosis, and beyond. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsilioni, I.; Taliou, A.; Francis, K.; Theoharides, T.C. Children with autism spectrum disorders, who improved with a luteolin-containing dietary formulation, show reduced serum levels of TNF and IL-6. Transl Psychiatry. 2015, 5, e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Asadi, S.; Panagiotidou, S. A case series of a luteolin formulation (NeuroProtek®) in children with autism spectrum disorders. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012, 25, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taliou, A.; Zintzaras, E.; Lykouras, L.; Francis, K. An open-label pilot study of a formulation containing the anti-inflammatory flavonoid luteolin and its effects on behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. Clin Ther. 2013, 35, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Shi, R.; Wang, X.; Shen, H.M. Luteolin, a flavonoid with potential for cancer prevention and therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008, 8, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C. Luteolin: The wonder flavonoid. Biofactors. 2021, 47, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Kim, M.Y.; Cho, J.Y. Immunopharmacological activities of luteolin in chronic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Kempuraj, D.; Iliopoulou, B.P. Mast cells, T cells, and inhibition by luteolin: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of multiple sclerosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007, 601, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Tsilioni, I.; Ren, H. Recent advances in our understanding of mast cell activation - or should it be mast cell mediator disorders? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019, 15, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilioni, I.; Taliou, A.; Francis, K.; Theoharides, T.C. Children with autism spectrum disorders, who improved with a luteolin-containing dietary formulation, show reduced serum levels of TNF and IL-6. Transl Psychiatry. 2015, 5, e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilioni, I.; Theoharides, T. Luteolin is more potent than cromolyn in their ability to inhibit mediator release from cultured human mast cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2024, 185, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Dilger, R.N.; Johnson, R.W. Luteolin inhibits microglia and alters hippocampal-dependent spatial working memory in aged mice. J Nutr. 2010, 140, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.D.; Rytych, J.L.; Amin, R.; Johnson, R.W. Dietary luteolin reduces proinflammatory microglia in the brain of senescent mice. Rejuvenation Res. 2016, 19, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, M.D.S.D.S.; Moragas Tellis, C.J.; Silva, A.R.; Brito, M.A.D.S.M.; Teodoro, A.J.; de Barros Elias, M.; Ferrarini, S.R.; Behrens, M.D.; Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque, C.F. Luteolin: A novel approach to fight bacterial infection. Microb Pathog. 2025, 204, 107519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Zhang, B.; Asadi, S.; Sismanopoulos, N.; Butcher, A.; Fu, X.; Katsarou-Katsari, A.; Antoniou, C.; Theoharides, T.C. Quercetin is more effective than cromolyn in blocking human mast cell cytokine release and inhibits contact dermatitis and photosensitivity in humans. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e33805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarinia, M.; Sadat Hosseini, M.; Kasiri, N.; Fazel, N.; Fathi, F.; Ganjalikhani Hakemi, M.; Eskandari, N. Quercetin with the potential effect on allergic diseases. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2020, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Bian, X.; Yao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, W.; Guo, C. Quercetin improves gut dysbiosis in antibiotic-treated mice. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 8003–8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, Z.; Ma, H.; Yue, Y.; Hao, K.; Li, J.; Xiang, Y.; Min, Y. Quercetin alleviates intestinal inflammation and improves intestinal functions via modulating gut microbiota composition in LPS-challenged laying hens. Poult Sci. 2023, 102, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, P.; Polissidis, A.; Kythreoti, G.; Sagnou, M.; Stefanatou, A.; Theoharides, T.C. Anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective polyphenols derived from the european olive tree, Olea europaea L., in long COVID and other conditions involving cognitive impairment. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C. Luteolin supplements: All that glitters is not gold. Biofactors. 2021, 47, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda-Chodak, A. The inhibitory effect of polyphenols on human gut microbiota. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012, 63, 497–503. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.B.; Tsilioni, I.; Leeman, S.E.; Theoharides, T.C. Neurotensin stimulates sortilin and mTOR in human microglia inhibitable by methoxyluteolin, a potential therapeutic target for autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016, 113, E7049–E7058, Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016, 113, E7138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616587113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel, A.B.; Theoharides, T.C. Methoxyluteolin inhibits neuropeptide-stimulated proinflammatory mediator release via mTOR activation from human mast cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017, 361, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taracanova, A.; Tsilioni, I.; Conti, P.; Norwitz, E.R.; Leeman, S.E.; Theoharides, T.C. Substance P and IL-33 administered together stimulate a marked secretion of IL-1β from human mast cells, inhibited by methoxyluteolin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018, 115, E9381–E9390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, M.A.; Theoharides, T.C. IL-33 stimulates human mast cell release of CCL5 and CCL2 via MAPK and NF-κB, inhibited by methoxyluteolin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019, 865, 172760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Patel, A.B.; Panagiotidou, S.; Theoharides, T.C. The novel flavone tetramethoxyluteolin is a potent inhibitor of human mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015, 135, 1044–1052.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Stewart, J.M.; Tsilioni, I. Tolerability and benefit of a tetramethoxyluteolin-containing skin lotion. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2017, 30, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippis, D.; Negro, L.; Vaia, M.; Cinelli, M.P.; Iuvone, T. New insights in mast cell modulation by palmitoylethanolamide. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013, 12, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrosino, S.; Schiano Moriello, A. Palmitoylethanolamide: a nutritional approach to keep neuroinflammation within physiological boundaries-a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 9526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolfo, E.; Cutuli, D.; Petrosini, L.; Caltagirone, C. Effects of palmitoylethanolamide on neurodegenerative diseases: a review from rodents to humans. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, S.; Brazis, P.; della Valle, M.F.; Miolo, A.; Puigdemont, A. Effects of palmitoylethanolamide on immunologically induced histamine, PGD2 and TNFalpha release from canine skin mast cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 133, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- D'Aloia, A.; Molteni, L.; Gullo, F.; Bresciani, E.; Artusa, V.; Rizzi, L.; Ceriani, M.; Meanti, R.; Lecchi, M.; Coco, S.; Costa, B.; Torsello, A. Palmitoylethanolamide modulation of microglia activation: characterization of mechanisms of action and implication for Its neuroprotective effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, N.; Cirillo, A.; Siniscalco, D. Beneficial effects of palmitoylethanolamide on expressive language, cognition, and behaviors in autism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2015, 325061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosková, E.; Vochosková, K.; Knop, V.; Stopková, P.; Kopeček, M. Histamine intolerance and anxiety disorders: pilot cross-sectional study of histamine intolerance prevalence in cohort of patients with anxiety disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2022, 65 (Suppl 1), S387–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnedl, W.J.; Schenk, M.; Lackner, S.; Enko, D.; Mangge, H.; Forster, F. Diamine oxidase supplementation improves symptoms in patients with histamine intolerance. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Casas, J.; Comas-Basté, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Lorente-Gascón, M.; Duelo, A.; Soler-Singla, L.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Diamine oxidase (DAO) supplement reduces headache in episodic migraine patients with DAO deficiency: A randomized double-blind trial. Clin Nutr. 2019, 38, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; You, H.; Ye, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Jiang, Y.C.; Tang, Z.X. Berberine ameliorates inflammation by inhibiting MrgprB2 receptor-mediated activation of mast cell in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024, 985, 177109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F. Berberine hydrochloride enhances innate immunity to protect against pathogen infection via p38 MAPK pathway. Front Immunol. 2025, 16, 1536143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori A, Brindisi G, Daglia M, Giudice MMD, Dinardo G, Di Minno A, Drago L, Indolfi C, Naso M, Trincianti C, Tondina E, Brunese FP, Ullah H, Varricchio A, Ciprandi G, Zicari AM; Nutraceutical and Medical Device Task Force of the Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy, Immunology (SIAIP). Exploring the role of lactoferrin in managing allergic airway diseases among children: unrevealing a potential breakthrough. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 1906. [CrossRef]

- Gunning, L.; O'Sullivan, M.; Boutonnet, C.; Pedrós-Garrido, S.; Jacquier, J.C. Effect of in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion on the antibacterial properties of bovine lactoferrin. J Dairy Res. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, S.; Mizuguchi, H.; Das, A.K.; Matsushita, C.; Maeyama, K.; Umehara, H.; Ohtoshi, T.; Kojima, J.; Nishida, K.; Takahashi, K.; Fukui, H. Suppression of histamine signaling by probiotic Lac-B: a possible mechanism of its anti-allergic effect. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008, 107, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Ping, L.; Cao, T.; Sun, L.; Liu, D.; Wang, S.; Huo, G.; Li, B. Immunomodulatory effects of the Bifidobacterium longum BL-10 on lipopolysaccharide-induced intestinal mucosal immune injury. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 947755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, D.A.; Frye, R.E. Cerebral folate deficiency, folate receptor alpha autoantibodies and leucovorin (folinic acid) treatment in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pers Med. 2021, 11, 1141, Erratum in: J Pers Med. 2022, 12, 721. DOI: 10.3390/jpm12050721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuid, A.N.; Jayusman, P.A.; Shuid, N.; Ismail, J.; Kamal Nor, N.; Mohamed, I.N. Association between viral infections and risk of autistic disorder: an overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, D.A.; Genuis, S.J.; Frye, R.E. Environmental toxicants and autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2014, 4, e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).