Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Topological and Differential Preliminaries

Manifolds and Smooth Structure

Homogeneous Spaces and Group Actions

Fiber Bundles and Local Triviality

Compactness and Topology at Infinity

Foundations of Projective Geometry

Projective Spaces

The Relationship Between Affine and Projective Geometry

Points at Infinity

Projective Transformations

Linear Maps and Projective Maps

The Projective General Linear Group

Cross-Ratio and Projective Invariants

Duality in Projective Geometry

The Principle of Duality

Incidence Relations

Conics and Quadrics

Projective Conics

The Dual of a Conic

Transition to Differential Geometry

Projective Structures and Local Coordinates

Tangent Spaces and Vector Fields

The Fubini-Study Metric

Chern Classes and Characteristic Classes

Advanced Topics and Modern Applications

Grassmannians and Schubert Calculus

Algebraic Curves and Riemann Surfaces

Moduli Spaces

Mirror Symmetry

Geometric Invariant Theory

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Appendix A: Linear Algebra Prerequisites

Vector Spaces and Linear Maps

- Vector addition:

- Scalar multiplication:

- 1.

- Associativity of addition:

- 2.

- Commutativity of addition:

- 3.

- Identity element: There exists such that for all

- 4.

- Inverse elements: For each , there exists such that

- 5.

- Compatibility of scalar multiplication:

- 6.

- Identity element of scalar multiplication: for all

- 7.

- Distributivity of scalar multiplication over vector addition:

- 8.

- Distributivity of scalar multiplication over field addition:

- 1.

- A set is linearly independent if the only solution to is .

- 2.

- A set spans V if every vector in V can be written as a linear combination of the .

- 3.

- A basis for V is a linearly independent set that spans V.

- 1.

- for all

- 2.

- for all and

Lie Algebras and Lie Brackets

- 1.

- Antisymmetry: for all

- 2.

- Jacobi identity: for all

- 1.

- Bilinearity: and

- 2.

- Antisymmetry:

- 3.

- Jacobi identity:

Differential Forms

- 1.

- A differential 1-form on M is a smooth section of the cotangent bundle .

- 2.

- A differential k-form is a smooth section of , the k-th exterior power of the cotangent bundle.

- 3.

- The space of differential k-forms on M is denoted .

- 1.

- Associativity:

- 2.

- Graded commutativity: for ,

- 3.

- Distributivity:

- 1.

- d is linear

- 2.

- for any function f (i.e., )

- 3.

- for (Leibniz rule)

- 4.

- (nilpotency)

Multilinear Algebra

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- for

Appendix B: Topology and Manifold Theory

Topological Spaces

- 1.

- 2.

- Arbitrary unions of sets in are in

- 3.

- Finite intersections of sets in are in

- 1.

- 2.

- If and , then there exists such that

- 1.

- (Kolmogorov) if for any two distinct points, there exists an open set containing one but not the other

- 2.

- (Fréchet) if for any two distinct points, each has an open neighborhood not containing the other

- 3.

- (Hausdorff) if any two distinct points have disjoint open neighborhoods

- 4.

- (Regular) if it is and for any closed set C and point , there exist disjoint open sets separating them

- 5.

- (Normal) if it is and any two disjoint closed sets can be separated by disjoint open sets

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- If , then

Compactness and Connectedness

Smooth Manifolds

- 1.

- A chart (or coordinate patch ) is a pair where is open and is a homeomorphism onto an open set V.

- 2.

- An atlas for M is a collection of charts such that .

- 3.

- Two charts and are -compatible if either or the transition map is a -diffeomorphism.

- 4.

- An atlas is a -atlas if any two charts in it are -compatible.

Tangent Spaces and Vector Fields

- 1.

- Bilinearity: and

- 2.

- Antisymmetry:

- 3.

- Jacobi identity:

Differential Forms and Exterior Calculus

- 1.

- If , then is the differential of f

- 2.

- for

- 3.

- (i.e., )

- 4.

- d commutes with pullbacks

Fiber Bundles and Principal Bundles

- 1.

- E (total space), M (base space), and F (fiber) are topological spaces

- 2.

- is a continuous surjection

- 3.

- For each , there exists a neighborhood U and a homeomorphism such that

- 1.

- The action preserves fibers: for all

- 2.

- The action is transitive on fibers

- 3.

- The bundle is locally trivial with respect to the G-action

- 1.

- for all (where is the fundamental vector field)

- 2.

- for all

Riemannian Geometry

- 1.

- Compatibility:

- 2.

- Torsion-free: for all vector fields

- 1.

- (antisymmetry in first two arguments)

- 2.

- (antisymmetry in last two arguments)

- 3.

- (block symmetry)

- 4.

- (first Bianchi identity)

Complex Manifolds and Projective Varieties

Characteristic Classes

Morse Theory

- 1.

- for all k

- 2.

- A point (if or )

- The product (if )

Morse Theory and Algebraic Geometry

- 1.

- f extends to a morphism

- 2.

- All critical points of f (as a smooth function on ) are non-degenerate

- 3.

- The restriction is a Morse function when X is defined over

- 1.

- The number of critical points of f is bounded below by

- 2.

- If X is defined over and has k connected components over , then the number of real critical points satisfies the classical Morse inequalities for each component

Applications to Geometric Synthesis

- 1.

- The Morse stratification provides a canonical cell decomposition of X

- 2.

- Each stratum is diffeomorphic to where is the m-disk

- 3.

- The boundary relations between strata encode the incidence geometry of X

- with index 0 (minimum)

- with index n (maximum)

Morse Theory and Sheaf Cohomology

- 1.

- The cohomology can be computed using the Morse complex associated to f

- 2.

- The local cohomology groups have controlled behavior as t passes through critical values

- 1.

- 2.

Computational Aspects

- 1.

- Identify critical points: Solve

- 2.

- Compute indices: Diagonalize the Hessian at each critical point

- 3.

- Construct gradient flow: Solve

- 4.

- Count flow lines: Determine boundary operator coefficients

- 5.

- Compute homology: Apply standard homological algebra

- Degeneracy: Generic perturbations may be needed to achieve non-degeneracy

- Stability: Small changes in f can dramatically alter the gradient flow

- Convergence: Numerical integration of gradient flows requires careful error control

Connections to Differential Geometry

- 1.

- The gradient flow preserves the metric structure along flow lines

- 2.

- Critical points correspond to singularities of the gradient vector field

- 3.

- The second variation formula relates the Morse index to sectional curvatures

Appendix C: Algebraic Geometry Foundations

Commutative Algebra Prerequisites

- 1.

- A ring is a set R with operations + and · such that is an abelian group, is a monoid, and multiplication distributes over addition.

- 2.

- An ideal I in a ring R is a subset such that I is closed under addition and for all .

- 3.

- A prime ideal is a proper ideal such that implies or .

- 4.

- A maximal ideal is a proper ideal that is not contained in any larger proper ideal.

- by definition

- If , then there exist with leading coefficients respectively and degrees . Then has leading coefficient (assuming ; if not, the leading coefficient is either a or b) and degree , so

- If and , then there exists with leading coefficient a and degree . Then has leading coefficient and degree , so

- 1.

- is an ideal containing I

- 2.

- 3.

- where the intersection is over all prime ideals containing I

- since

-

If , then for some . By the binomial theorem:Each term either has (so is divisible by ) or (so is divisible by ). Therefore , so

- If and , then for some n, so , hence

- 1.

- 2.

- If I is a maximal ideal, then consists of a single point

- 3.

- If vanishes on , then for some

Affine and Projective Varieties

- 1.

- Affine varieties in

- 2.

- Radical ideals in

Schemes

- since no prime ideal can contain the unit ideal

- since every prime ideal contains

- since is proper, so

- If , then . Since is prime, , so

- On objects:

- On morphisms: A ring homomorphism induces a morphism of schemes by

- On objects:

- On morphisms: A morphism induces

- naturally

- naturally for affine schemes

Sheaves and Cohomology

- 1.

- For each open set , an abelian group

- 2.

- For each inclusion of open sets, a restriction map

- 1.

- Identity: If and for all i, then

- 2.

- Gluing: If satisfy for all , then there exists with for all i

- Identity : If agree on each in a cover, then for all , so

- Gluing : Given compatible sections , define for any i such that . This is well-defined by compatibility and gives a section in

- 1.

- is finite-dimensional over k for all i

- 2.

- for

- 3.

- For sufficiently large n, for all

- The fact that X can be covered by finitely many affine open sets

- Coherent sheaves on affine varieties have finite-dimensional cohomology

- Mayer-Vietoris sequences relating cohomology on overlaps

- Induction on dimension

- The exact sequence relating a variety to its hyperplane sections

- The fact that hyperplane sections have smaller dimension

- Use the fact that X embeds in projective space

- Reduce to the case of using projection formulas

- For , use explicit computations with the Čech complex

- The key insight is that for large n, the sheaf has many global sections, making higher cohomology vanish

- (homogeneous polynomials of degree n)

- for and

- for

- Construction of the dualizing sheaf

- Proof that it satisfies the duality property

- Verification of the natural isomorphism

Appendix D: Category Theory and Homological Algebra

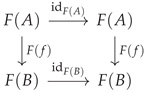

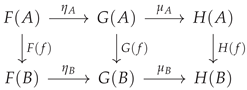

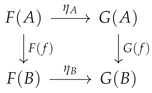

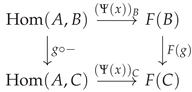

Categories and Functors

- 1.

- A class of objects

- 2.

- For each pair of objects , a set of morphisms

- 3.

- For each object A, an identity morphism

- 4.

- A composition operation: if and , then

- 1.

- Associativity:: For morphisms , , , we have .

- 2.

- Identity: For any morphism , we have and .

- 1.

- : objects are sets, morphisms are functions

- 2.

- : objects are groups, morphisms are group homomorphisms

- 3.

- : objects are rings, morphisms are ring homomorphisms

- 4.

- : objects are topological spaces, morphisms are continuous maps

- 5.

- : objects are vector spaces over field k, morphisms are linear maps

- 1.

- A function

- 2.

- For each pair of objects , a function

- 1.

- Objects are functors

- 2.

- Morphisms are natural transformations between functors

Limits and Colimits

- 1.

- For each morphism in , we have

- 2.

- For any object X with morphisms satisfying the same compatibility, there exists a unique morphism such that for all j

- 1.

- The product is the limit of the diagram

- 2.

- The coproduct is the colimit of the same diagram

- 3.

- The equalizer of is

- 4.

- The coequalizer is the corresponding colimit

Abelian Categories

- 1.

- It has a zero object 0 (both initial and terminal)

- 2.

- For any objects , the set has an abelian group structure

- 3.

- Composition is bilinear

- 4.

- Finite products exist (equivalently, finite coproducts exist)

- 1.

- It is additive

- 2.

- Every morphism has a kernel and cokernel

- 3.

- Every monomorphism is a kernel and every epimorphism is a cokernel

- 1.

- Every morphism can be factored as an epimorphism followed by a monomorphism

- 2.

- The canonical factorization gives

- 3.

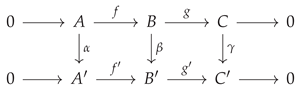

- The snake lemma holds

- 1.

- f is a monomorphism ()

- 2.

- g is an epimorphism ()

- 3.

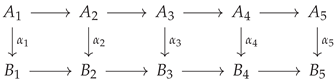

Chain Complexes and Homology

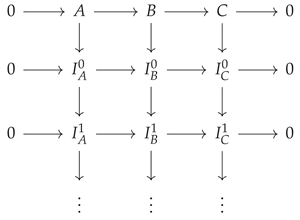

Derived Functors

- 1.

- An object P is projective if is exact

- 2.

- An object I is injective if is exact

- 1.

- P is projective

- 2.

- For any epimorphism and morphism , there exists such that

- 2.

- P is a direct summand of a free object (in categories with enough projectives)

Spectral Sequences

- 1.

- 2.

- 1.

- First taking cohomology with respect to the F-differential, then applying G

- 2.

- First applying G, then taking total cohomology

Appendix Topos Theory Connections

- 1.

- Finitely complete and cocomplete

- 2.

- Cartesian closed

- 3.

- Has a subobject classifier Ω

- 1.

- Constructing the site from subterminal objects

- 2.

- Showing the Yoneda embedding extends to an equivalence

- 3.

- Verifying that sheafification preserves the topos structure

Applications and Examples

- 1.

- 2.

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- Long exact sequences in both variables

Advanced Topics

- 1.

- An automorphism (translation functor)

- 2.

- A class of distinguished triangles

- 1.

- and

- 2.

- for and

- 3.

- For each , there exists a distinguished triangle with and

- 1.

- Coherent duality theory

- 2.

- Intersection theory via derived categories

- 3.

- Motivic cohomology

- 4.

- Stability conditions and moduli problems

Appendix E: Representation Theory

Group Representations

Character Theory

Appendix F: Further Reading and Advanced Topics

Projective Geometry

- Hartshorne, R. Foundations of Projective Geometry - Classical approach with emphasis on synthetic methods

- Baer, R. Linear Algebra and Projective Geometry - Algebraic foundation using vector spaces

- Coxeter, H.S.M. Projective Geometry - Geometric intuition and classical results

- Semple, J.G. and Kneebone, G.T. Algebraic Projective Geometry - Modern algebraic treatment

- Stillwell, J. The Four Pillars of Geometry - Includes projective geometry in historical context

Differential Geometry

- Lee, J. Introduction to Smooth Manifolds - Comprehensive modern treatment

- Spivak, M. Differential Geometry - Multi-volume classical approach

- Kobayashi, S. and Nomizu, K. Foundations of Differential Geometry - Advanced reference

- Abraham, R. and Marsden, J. Foundations of Mechanics - Applications to physics

- Milnor, J. Topology from the Differentiable Viewpoint - Elegant introduction

- Guillemin, V. and Pollack, A. Differential Topology - Fundamental techniques

Algebraic Geometry

- Hartshorne, R. Algebraic Geometry - Standard graduate reference

- Shafarevich, I.R. Basic Algebraic Geometry - Two-volume introduction

- Griffiths, P. and Harris, J. Principles of Algebraic Geometry - Complex algebraic geometry

- Mumford, D. The Red Book of Varieties and Schemes - Schemes introduction

- Eisenbud, D. Commutative Algebra with a View Toward Algebraic Geometry - Essential background

- Liu, Q. Algebraic Geometry and Arithmetic Curves - Modern approach with arithmetic

Advanced Topics

- Mumford, D. Geometric Invariant Theory - Classical invariant theory and quotients

- Hori, K. et al. Mirror Symmetry - Physics-inspired algebraic geometry

- Fulton, W. Intersection Theory - Intersection multiplicities and Chow rings

- Grothendieck, A. Éléments de géométrie algébrique (EGA) - Foundational scheme theory

- Grothendieck, A. Séminaire de Géométrie Algébrique (SGA) - Advanced topics in algebraic geometry

- Deligne, P. et al. Cohomologie étale (SGA 4½) - Étale cohomology

- Vakil, R. The Rising Sea: Foundations of Algebraic Geometry - Modern comprehensive treatment

Specialized References

Homological Algebra

- Weibel, C. An Introduction to Homological Algebra - Comprehensive introduction

- Rotman, J. An Introduction to Homological Algebra - Elementary approach

- MacLane, S. Homology - Classical reference

- Gelfand, S. and Manin, Y. Methods of Homological Algebra - Advanced techniques

Category Theory

- MacLane, S. Categories for the Working Mathematician - Standard reference

- Awodey, S. Category Theory - Modern introduction

- Riehl, E. Category Theory in Context - Contemporary approach

- Leinster, T. Basic Category Theory - Concise introduction

Representation Theory

- Serre, J.-P. Linear Representations of Finite Groups - Classical introduction

- Fulton, W. and Harris, J. Representation Theory: A First Course - Comprehensive treatment

- James, G. and Liebeck, M. Representations and Characters of Groups - Elementary approach

- Bump, D. Lie Groups - Lie group representations

Algebraic Topology

- Hatcher, A. Algebraic Topology - Modern standard reference

- Spanier, E. Algebraic Topology - Comprehensive classical treatment

- May, J.P. A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology - Efficient coverage

- Bredon, G. Topology and Geometry - Includes geometric topology

- 1.

- The zero vector is unique

- 2.

- For each , the additive inverse is unique

- 3.

- for all

- 4.

- for all

- 5.

- for all

- 6.

- If , then either or

- 1.

- Suppose and are both zero vectors. Then by the definition of zero vector.

- 2.

- Suppose and are both additive inverses of v. Then:

- 3.

- We have . Adding to both sides gives .

- 4.

- Similarly, , so .

- 5.

- We have , so .

- 6.

- If , then exists in F, and .

- 1.

- A set is linearly independent if the only solution to is .

- 2.

- A set is linearly dependent if it is not linearly independent.

- 3.

- A set spans V if every vector in V can be written as a linear combination of vectors in S.

- 4.

- A basis of V is a linearly independent set that spans V.

- 1.

- for all (additivity)

- 2.

- for all (homogeneity)

- 1.

- 2.

- for all

- 3.

- 4.

- If is linearly dependent in V, then is linearly dependent in W

- 1.

- . Adding to both sides: .

- 2.

- .

- 3.

- By induction on k. The base cases follow from the definition. If the statement holds for k, then:

- 4.

-

If is linearly dependent, then there exist scalars , not all zero, such that . Applying T:Since not all are zero, is linearly dependent.

- 1.

- The kernel (or null space) of T is

- 2.

- The image (or range) of T is

Quotient Spaces

- Zero element: serves as the zero vector in

- Additive inverse: is the inverse of

- Associativity and other properties follow from the corresponding properties in V

Dual Spaces and Bilinear Forms

- 1.

- 2.

- 1.

- Symmetric if for all

- 2.

- Alternating if for all

- 3.

- Non-degenerate if for all implies

- 1.

- B is symmetric if and only if M is symmetric

- 2.

- B is alternating if and only if M is skew-symmetric and has zero diagonal

- 3.

- B is non-degenerate if and only if M is invertible

- 1.

- for all if and only if for all coordinate vectors, which occurs if and only if .

- 2.

- for all v means for all . This implies and for , so M is skew-symmetric with zero diagonal.

- 3.

- B is non-degenerate if and only if for all v implies . In matrix terms, this means implies , which occurs if and only if M is invertible.

Matrix Groups

- 1.

- is a normal subgroup of

- 2.

- (the multiplicative group of F)

- 3.

- If or , then and are Lie groups

- 1.

-

Subgroup: since . If , then , so . If , then , so .Normal: For and : So .

- 2.

-

Define by . This is a group homomorphism since . We have .For surjectivity, given , the matrix has determinant .By the first isomorphism theorem, .

- 3.

- For or , is an open subset of (the complement of ), and matrix multiplication and inversion are smooth operations. is a closed submanifold since det is smooth and 1 is a regular value.

- 1.

- The orthogonal group

- 2.

- The special orthogonal group

- 3.

- The unitary group where is the conjugate transpose

- 4.

- The special unitary group

- 1.

- and are compact Lie groups

- 2.

- and are connected components of and respectively

- 3.

- and are continuous homomorphisms

- 1.

-

Compactness: If , then implies for each standard basis vector . Therefore, all entries of A are bounded, making a bounded subset of . It’s also closed as is the preimage of under the continuous map . By Heine-Borel, is compact.Similarly for using .

- 2.

-

For , , so . The map is continuous, and is discrete, so is a decomposition into two clopen sets.For , if , then , so , meaning .

- 3.

- The determinant function is continuous as a polynomial in the matrix entries, and the codomain inherits the subspace topology.

References

- R. Baer. Linear Algebra and Projective Geometry. Academic Press, New York, 1952.

- H.S.M. Coxeter. Projective Geometry, 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1974.

- R. Hartshorne. Foundations of Projective Geometry. W.A. Benjamin, New York, 1967.

- P. Samuel. Projective Geometry. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1988.

- O. Veblen and J.W. Young. Projective Geometry, 2 volumes. Ginn and Company, Boston, 1910-1918.

- D.A. Cox, J. Little, and D. O’Shea. Ideals, Varieties, and Algorithms: An Introduction to Computational Algebraic Geometry and Commutative Algebra, 4th edition. Springer, New York, 2015.

- W. Fulton. Intersection Theory, 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1998.

- P. Griffiths and J. Harris. Principles of Algebraic Geometry. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1994.

- R. Hartshorne. Algebraic Geometry. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1977.

- D. Mumford. The Red Book of Varieties and Schemes, 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1999.

- I.R. Shafarevich. Basic Algebraic Geometry 1: Varieties in Projective Space, 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1994.

- R. Abraham, J.E. Marsden, and T. Ratiu. Manifolds, Tensor Analysis, and Applications, 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1988.

- S. Kobayashi and K. Nomizu. Foundations of Differential Geometry, 2 volumes. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1996.

- J.M. Lee. Introduction to Smooth Manifolds, 2nd edition. Springer, New York, 2013.

- M. Spivak. A Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry, 5 volumes, 3rd edition. Publish or Perish, Houston, 1999.

- W. Ballmann. Lectures on Kähler Manifolds. European Mathematical Society, Zürich, 2006.

- J.-P. Demailly. Complex Analytic and Differential Geometry. Institut Fourier, Grenoble, 1997.

- P. Griffiths and J. Harris. Principles of Algebraic Geometry. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1979.

- R.O. Wells Jr. Differential Analysis on Complex Manifolds, 3rd edition. Springer, New York, 2008.

- I. Dolgachev. Lectures on Invariant Theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003.

- D. Mumford, J. Fogarty, and F. Kirwan. Geometric Invariant Theory, 3rd edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1994.

- P.E. Newstead. Introduction to Moduli Problems and Orbit Spaces. Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bombay, 1978.

- W. Fulton. Young Tableaux: With Applications to Representation Theory and Geometry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997.

- P. Griffiths. Introduction to Algebraic Curves. American Mathematical Society, Providence, 1989.

- S.L. Kleiman and D. Laksov. Schubert calculus. American Mathematical Monthly, 79:1061–1082, 1972.

- J. Harris and I. Morrison. Moduli of Curves. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1998.

- D. Mumford. Towards an Enumerative Geometry of the Moduli Space of Curves. In Arithmetic and Geometry, volume 2, pages 271–328. Birkhäuser, Boston, 1983.

- R. Vakil. The moduli space of curves and its tautological ring. Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 53(10):1186–1196, 2006.

- D.A. Cox and S. Katz. Mirror Symmetry and Algebraic Geometry. American Mathematical Society, Providence, 1999.

- K. Hori, S. Katz, A. Klemm, R. Pandharipande, R. Thomas, C. Vafa, R. Vakil, and E. Zaslow. Mirror Symmetry. American Mathematical Society, Providence, 2003.

- D.R. Morrison. What is mirror symmetry? Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 62(11):1265–1268, 2015.

- D.A. Cox, J.B. Little, and H.K. Schenck. Toric Varieties. American Mathematical Society, Providence, 2011.

- W. Fulton. Introduction to Toric Varieties. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1993.

- J.W. Milnor and J.D. Stasheff. Characteristic Classes. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1974.

- R. Bott and L.W. Tu. Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1982.

- H.M. Farkas and I. Kra. Riemann Surfaces, 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1992.

- R. Miranda. Algebraic Curves and Riemann Surfaces. American Mathematical Society, Providence, 1995.

- J. Dieudonné. History of Algebraic Geometry. Wadsworth Advanced Books & Software, Monterey, 1985.

- J. Gray. Worlds Out of Nothing: A Course in the History of Geometry in the 19th Century. Springer, London, 2007.

- F. Klein. Vorlesungen über höhere Geometrie, 3rd edition. Springer, Berlin, 1926.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).