1. Introduction

Hilbert proposed a list of 23 open mathematical problems in 1900. Of which the second problem is about the logical foundation of the fast-growing mathematical architecture. Gödel proved the independent result and incompleteness theorem in 1931. Since then, metalogic as a scientific domain has been seemingly quiet and its Gödel methods have seemed frozen for about a century. This situation does not meet Hilbert’s vision. Penrose proposed the twistor theory in 1960s, and it became a well-developed mathematical framework. However, the twistor theory has not become popular in applications. The work reported in the present paper aims to integrate metalogic and the twistor theory.

Integration science is an advancement of cognitive science. This paper opens a new topic called metalogic geometry that aims to integrate metalogic with the mathematical twistor theory. We first revisit Gödel methods used in metalogic including Gödel numbering, expressibility, definability, self-referential statement, and proof (direvation). Second, it revisits the core ideas of the twistor theory. To follow the Penrose idea: Light rays as twisters, we define the notions of Gödel ray and Penrose cone. By the expressibility and definability, a pair of Gödel numbers composes a Gödel ray (or Tarski ray). A family of Gödel ray composes a Penrose cone. The intersection point of a Penrose cone yields a Gödel point. Gödel rays are projected as twistors. Each Gödel point is projected to a Riemann celestial sphere. Twistors and Riemann spheres assemble the picture of twistor space. The meanings of this work are discussed in the concluding remarks. The rest contents of this paper are as following:

§2. Revisit Gödel Methods

§3. Revisit Twistor Theory

§4. Gödel Rays as Twisters

§5. Projections from the Ordinary Space to the Twistor Space

§6. Concluding Remarks

Note that §2 is necessary to follow §4 and §5, which contains main contents of the present paper. §3 is mostly about pure mathematical definitions, which pre-assume some mathematical backgrounds. After reading §2, one would have no difficulty to go through §4 and §5 directly.

2. Revisit Gödel Methods

We first introduce the Gödel numbering method. Mathematical language always deals with symbols, formulas, and derivations. For a mathematical framework, even though its base domains (such as real or complex fields) are uncountable infinities (i.e., the continuum), the number of symbols used to denote variables, functions, operators, etc., is infinite but countably many. Thus, we can have an effective procedure to mechanically assign a unique odd number to each and every symbol in order, called the Gödel number.

Definition 1 (Gödel number of a symbol). For a given symbol e, its Gödel number can be written as which can be seen as a function or an odd number.

Definition 2 (the Gödel number of a formula). A formula is a finite string of symbols, written as

The Gödel number of a formula

can be calculated by

where

is the first

i prime numbers in its natural order, and

is the Gödel number of the

ith symbol in the formula

L.

Definition 3 (the Gödel number of a derivation). A derivation is a finite sequence of formulas, written as

. The Gödel number of a derivation can be calculated by

where

is the Gödel number of the

ith formula in the sequence of a derivation (proof). The Gödel number of any given formula or derivation is always an even number, which is also a composite number.

The above method is called Gödel numbering. The beauty and power of Gödel numbering is that, based on the fundamental theorem of arithmetic (i.e., the unique decomposition theorem of primes), from a given Gödel number we can uniquely recapture the original derivation, the original formula, or the original symbol used in the context.

A necessary note is worth making here. We assume readers are familiar with the first-order logic (PL), the arithmetic theory (N), and the first-order theory (𝓝) (Margaris, 1967); The system 𝓝 is an integration of PL and N. That integration involves the second formalization. The first order theory is a well-developed mathematical framework. Our plan for further research is to develop the first order metalogic geometry in steps. But as an initial step, we can omit most formal and mathematical descriptions. Rather, we only provide necessary contents to make this paper conceptually self-sufficient and instrumentally self-contained.

In the first order theory, it makes the distinction of the intuitive numbers and the corresponding set-theoretic enumerers. Intuitive natural numbers used in N are given by , and the corresponding enumerers used in 𝓝 are denoted by bold . Enumerers are constructed by starting from the empty set and the so-called successor function, such that , { , and so forth. In the following, we introduce Godel’s theorem first, and Tarski’s theorem second.

Definition 4 (Expressibility). If holds in N, then is provable in 𝓝. If does not hold in N, then ¬ is provable in 𝓝.

Definition 5 (Consistency). For any given formula in 𝓝, either is provable, or else ¬ is provable, but not both.

For a given formula L, denote its proof as Bew(L). Assume , where and are Gödel numbers. We have

Definition 5 (Gödel relation). Assume the relation , then by the expressibility, the corresponding function term is provable (or derivable) in 𝓝.

Gödel constructed a formula,

in which

is a free variable. Let

, by substituting

with

, we have,

This is a so-called self-referential statement.

Gödel First Theorem Neither nor is provable in 𝓝.

We now briefly sketch a proof. First, we prove that is not provable. Assume for contradiction that is provable, then it must have a proof, write , let and , so that . By the expressibility, must be provable in 𝓝; but said that for any, . This contradiction shows that the assumption is impossible. Hence, is not provable in 𝓝.

Second, we prove that is unprovable in 𝓝. Assume for contradiction that is provable. Then by consistency, is unprovable, so that for any j, . Hence, for any j, does not hold in ; by expressibility, , for any. As such, by , we have , which means is provable in 𝓝. This contradicts to the assumption that is unprovable. Thus is unprovable in 𝓝.

The above result shows that the consistency of 𝓝 is independent of 𝓝. Now let us speculate about what expresses. is a self-reflection sentence, it says that is unprovable, and we have just proved it above; thus, is true, but not provable in 𝓝, which by definition means that 𝓝 is incomplete. This is the well-known Gödel Incompleteness Theorem. We now turn to Tarski’s indefinability theorem.

Definition 6 (Definability). Let , and , we can hold a binary relation in . Accordingly, we say is definable in 𝓝, meaning has a model, which is not null.

Tarski introduced a new predicate of being true, denoted by

T, and he constructed a sentence below:

Let

, substituting

by

, we have

Let

, we have

which holds in

; hence,

is definable in 𝓝. Then, by standard logic, we can infer

. Now we show that

T is not definable, meaning its model is null. Denote

by

L. If

L is pre-assumed as true, denote it by

, and write

As such, we may assume for contradiction that

T had a model

X;

Since, i.e.,is the Gödel number of . By the definition of ,we have , hence is definable in 𝓝. However, recalling the logical structure of which is a universally quantified conditional statement, we may infer , i.e., is not true in model ; hence, , which shows that may only be null. In other words, since T has no model, the truth predicate function is arithmetically undefinable.

3. Revisit Twistor Theory

The philosophy of twister theory has three core ideas. First, it holds a principle of composibility and assembling. In other words, for the twistor theory, the twistor space can be assembled but not a priori. Second, its building blocks at the bottom are lines but not points. Third, the principle of shortest path, which means the straight lines, such as light rays or geodesics are fundamental. As Penrose characterized (2004), “Light rays as twistors”.

Some readers may well be interested in mathematical definitions of twistors and twistor space. There are different angles to do so. We provide several of them in the following.

Our first definition of a twistor is geometric one (Huggett & Tod, 1985/1994, Chapter 7). A twistor is defined as a spinor field

in Minkowski space M satisfying the twistor equation

The

twistor space T, the vector space of solutions to the formula above, is a four-dimensional complex vector space and may be coordinatized with respect to a choice of origin, by a pair of spinors,

Our second definition of twistor space is in terms of a vector field (Ward & Wells Jr., 1990, §1.2). Let V be a fixed complex vector space of dimension

n, and let

} be a sequence of positive integers satisfying

We define

and this is called a flag manifold of type

}. We now want to use the notion of flag manifold to define the fundamental vector space. The vector space

T denote a fixed four-dimensional vector space. This vector space

T will be called the space of twistors or twistor space.

Our third definition of a twistor space is from the group theoretic perspectives (Penrose, 2004). In physics, we probably more familiar with the notion of spinor than twistor; for example, the Weyl 2-spinor and Dirac 4-spinor in quantum field theory. From the group theoretic perspectives, consider the conformal group . The shortest way to describe a (Minkowski-space) twistor is to say that it is a reduced spinor (or half spinor) for . For a 2-dimensional space, on which a pseudo-orthogonal group acts, the space of reduced spinor is -dimensional. Here, (and ), so we have a 4-dimensional space of reduced spinors, referred to as twistor space.

Moreover, the light (null) cone may be characterized in terms of the so-called Clifford null geodesic bundle. The Clifford null geodesic are parallel meet one point. In

Section 4, we will define the notion of the Penrose cone, which may be characterized by the Clifford null geodesic bundle.

4. Gödel Rays as Twisters

In general, the Definition 4 of the expressibility, can be any n-ary relations. In particular, by Definition 5, what exactly the Gödel relation could mean is an interesting inquiry. Similarly, by Definition 6, what exactly the Tarski relation could mean is also an interesting inquiry. For any two Gödel numbers, they may be used to calculate the distance between the two points. They may be used to compose a complex number (), which has an exponential form with a phase . In the gauge field theory, this is called the dynamic phase. Also, by this phase , the two Gödel numbers may be used to compose a vector. Indeed, by Penrose (2004), the twister theory can maximumly utilize the advantage of complex numbers. Geometrically, between any pair of Gödel numbers, a line can be drawn between them. Specifically, in the special relativity, we assume such a line is straight which is called a light ray. As Penrose characterized in the title of §33.2 (2004): Twisters as Light rays. Accordingly, in the following, we define Gödel rays, Tarski rays, and Penrose rays as twisters.

Definition 7 (Gödel ray). Consider the Gödel relation in Definition 5, we postulate that there is straight line connecting the two Gödel numbers ; call such a straight line the Gödel ray and denote it as . Gödel rays are twisters.

Definition 8 (Tarski ray). Consider the Tarski relation in Definition 6, we postulate that there is a straightly line connecting the two Gödel numbers ; call such a straight line the Tarski ray and denote it as . Tarski rays are twisters.

Definition 9 (Penrose ray). In general, for any given pair of Gödel numbers , we postulate that there is a straight line connecting them. This straight line is called the light ray or Penrose ray, denoted as P. Penrose rays are twisters.

Note that there is a distinction between Gödel ray (as well as Tarski ray) and Penrose ray. The Gödel ray reflects certain ‘local causality’, which connects the Gödel number of a formula (2.3) and the Gödel number of the proof of a daughter formula (2.4). The Tarski ray reflects the local causal relation of a mother formula (2.5) and the Gödel number of the self-referential daughter formula (2.6). However, The Penrose ray just carries some ‘global logical causality’ between any pair of Gödel numbers.

Definition 10 (Point in twister space). The twister space is assembled, in which each point is a twister. From the projective geometry perspective, each Penrose ray in the classical space is projected to a twister point in the twister space.

Let

be a formula, where

is

ith symbol which by Definition 1 has the Gödel number

. By Definition 2 and formula (2.1),

has the Gödel number

where

is the first

ith prime number in its natural order. Thus, by Definition 9, the pair of two Gödel numbers forms a Penrose Ray

P[

,

. Note that Penrose rays are twistors.

We now introduce the notions of

Penrose Cone and

Gödel Point. The symbol

may occur in many formulas, such as

. Assume that the symbols

and

are the same, we have

. However, in general,

. Thus, the two Penrose rays are different; i.e.,

Definition 11 (Penrose Cone and Gödel Point). Let be a family of Penrose Rays as characterized above. We assume that the same symbol occurs in each Ray. This family of Penrose Rays is called the Penrose Cone and the shared Gödel number is the Gödel Point.

5. Projections from the Ordinary Space to the Twistor Space

The projection from the Penrose cone and the Gödel point to the twistor space can be shown in three steps. Each step can be well characterized mathematically (Penrose, 2004; Bailey and Baston, (Eds.),1990; Huggett and Tod, 1985/1994; Ward and Wells, 1990). In the following, we only briefly explain these steps intuitively with schematic diagrams.

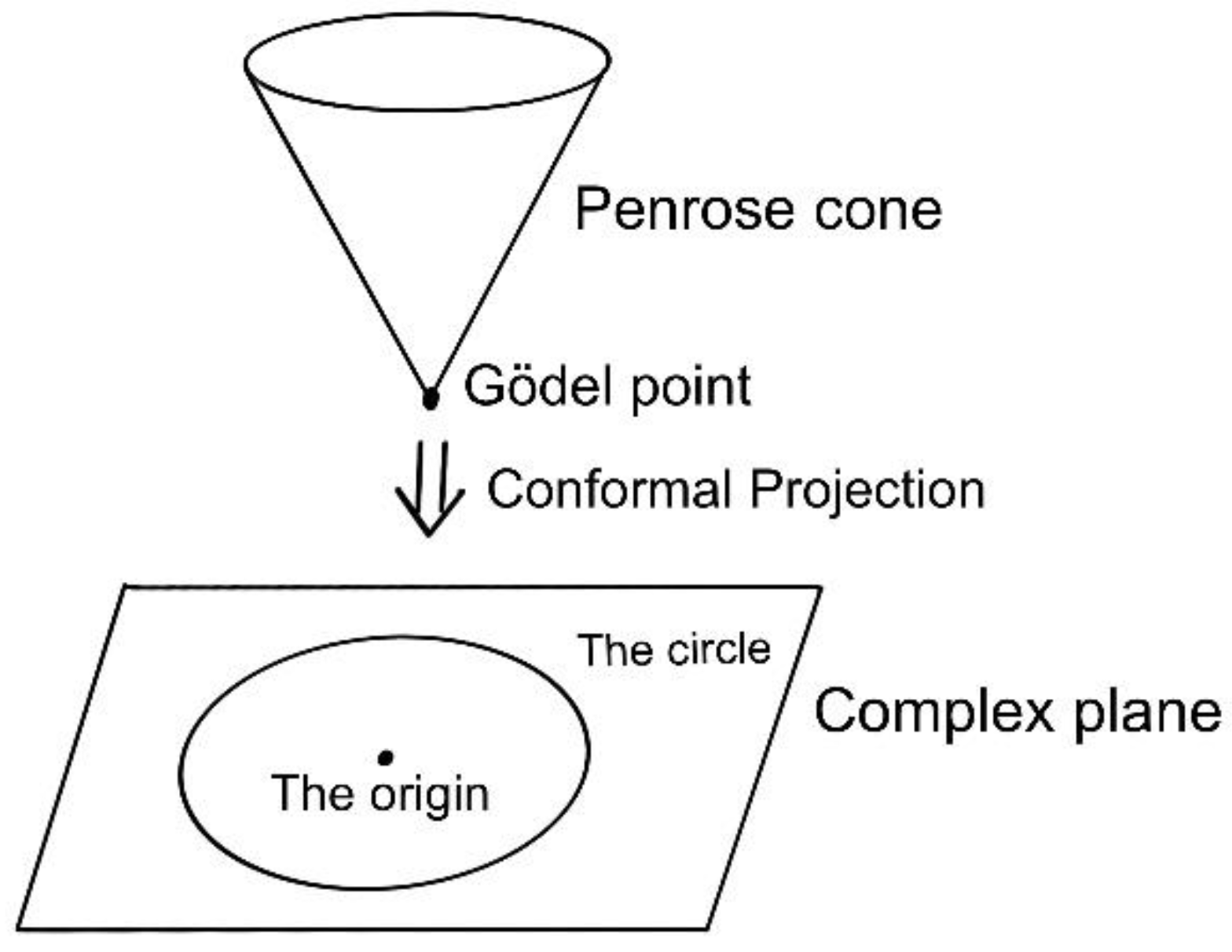

Step 1. By the Riemann analytic continuation, the Penrose cone can be projected to a circle on the complex plane with the Gödel point as the origin (see Figure 1 below). This projection is conformal without a gauge structure. Note that this circle is itself a line, which can be treated as a twistor.

Figure 1

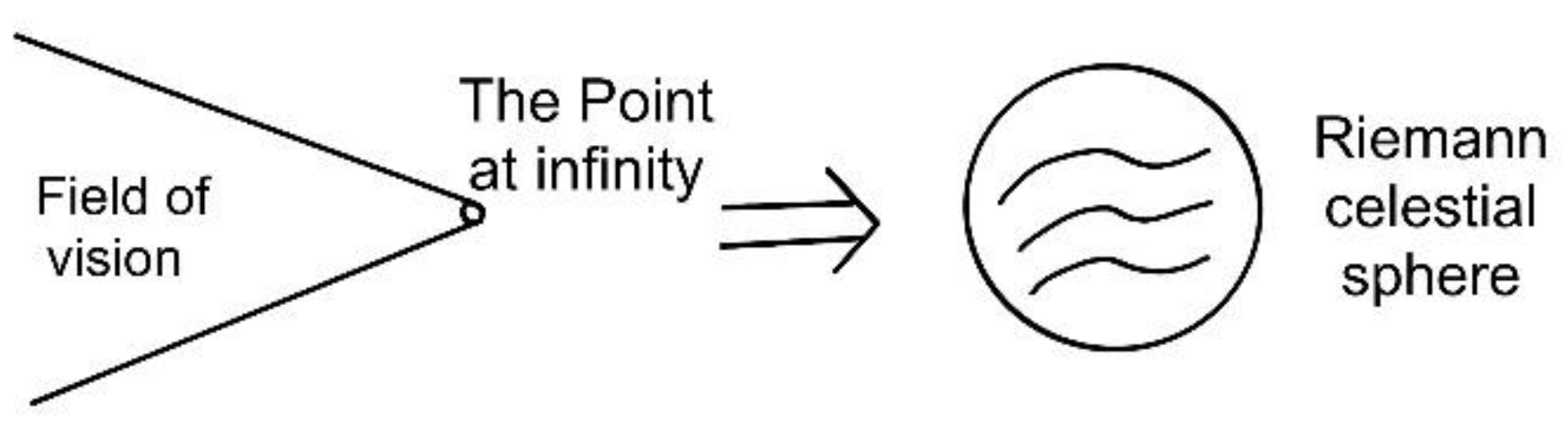

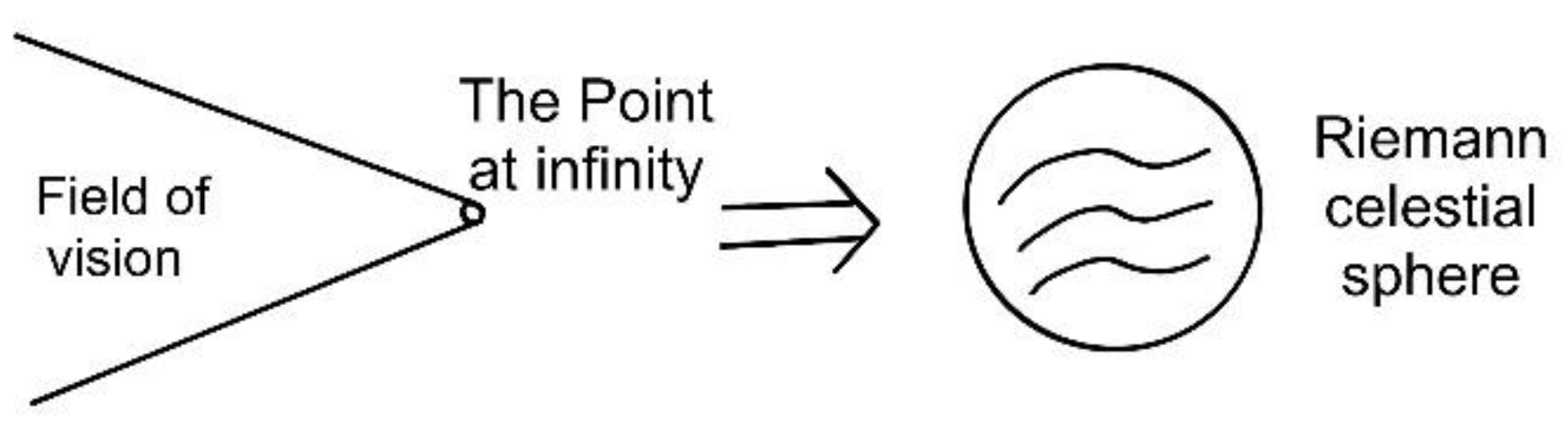

Step 2. In the special relativity, each event in the Minkowski spacetime can be seen as a permissible observer. The Penrose cone can be treated as the event horizon of this observer. Also, imagine the Penrose cone as a field of vision. Then, by the affine geometry, the corresponding Gödel point can be treated as the “point at infinity’. This point of infinity is characterized as the Riemann celestial sphere in the twistor space (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2

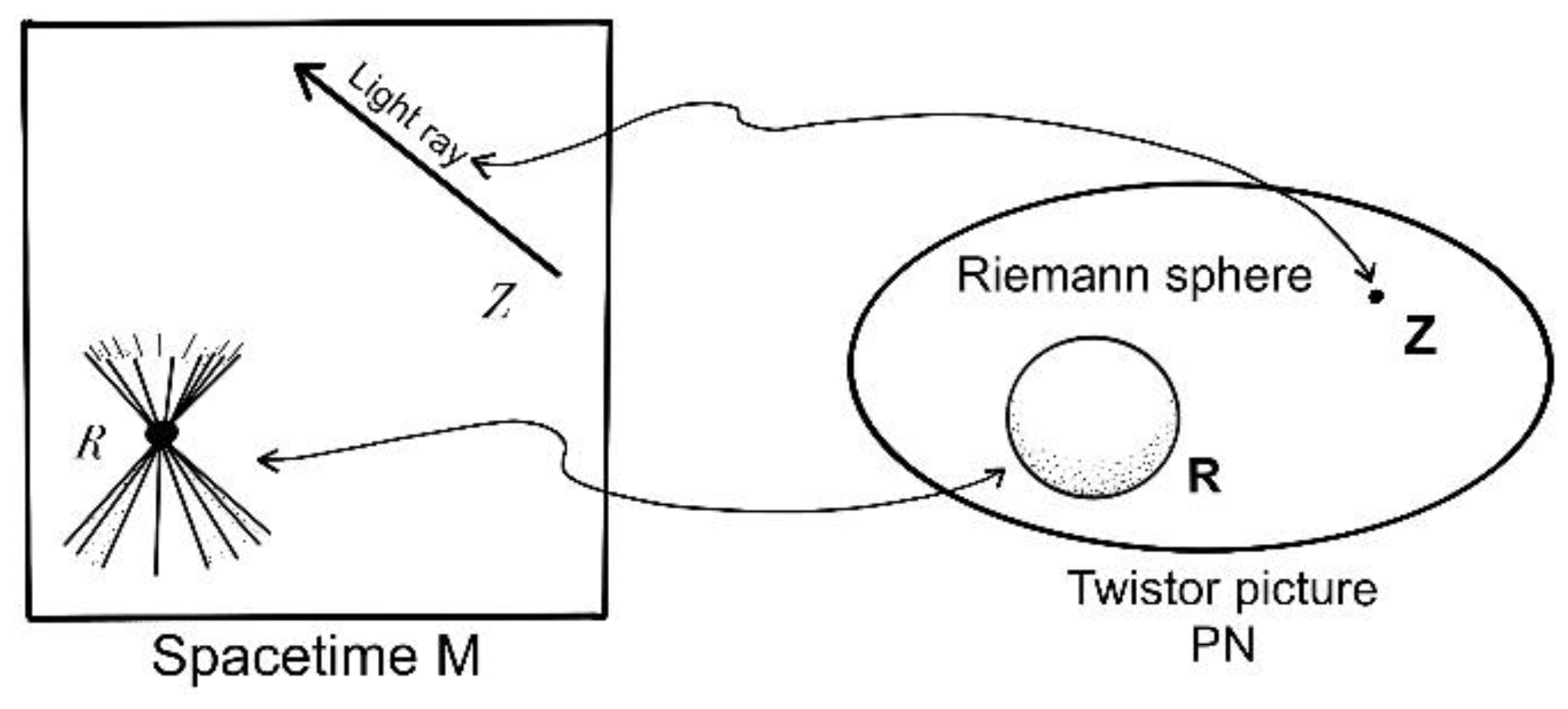

Step 3. We are now clear about how to assemble a basic twistor space of metalogic. The twistor point is composed by a line, namely, a Gödel ray. We may think of a twistor as representing a Gödel ray in ordinary space (e.g., Minkowski spacetime). Figure 3 (see below) is originally from Penrose (§33.2, 2004). His explanation must be most accurate and insightful (with slight modifications), “One can regard such a light ray (e.g., Gödel ray) as providing the primitive ‘causal link’ between a pair of events. But events are themselves to be regarded as secondary constructs. These being obtained from their roles as intersections of light rays (e.g., Tarski rays). In fact, we may characterize an event R (spacetime point R) by means of the family of light rays (Gödel rays) that pass-through R. Thus, whereas in the normal spacetime picture a light ray (e.g., Penrose ray) Z is a locus and an event R is a point. There is a striking reversal of this in twistor space, since now the light ray (Gödel ray) is described as a point Z and an event is described as a locus R”. The Riemann celestial sphere is now composed by the Gödel point of a Penrose cone (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The locus R inside the picture of twistor space PN describes the ‘celestial sphere’ of R being regarded as the family of Gödel rays through R. This sphere is naturally a Riemann sphere which is a complex 1-dimensional space.

6. Concluding Remarks

Remark 1. The work reported in the present paper integrates metalogic and the twistor theory. The results re-excite the power of both and create a new direction of study.

Remark 2. In the domain of artificial intelligence, there is a long-standing controversy about what intelligence is. Roughly speaking, the symbolic approach and traditional AGI claim that intelligence means reasoning. Indeed, the early expert systems in artificial intelligence mostly studied machine reasoning. On the other hand, the connectionist approach and LLMs argue that intelligence means learning. The debates continuous. One of the problems is the lacking of a mathematical language which can be shared by both approaches. In Wittgenstein’s term, they are playing language games. As we know, the spin network and the Ising model have important application in machine language learning models. It is not well-known that the twistor theory has a root in spin network. This paper finds a way to apply the twistor theoretic language in developing metalogic geometry. Thus, this paper provides a possible path for a unified account of the two major competing approaches in artificial intelligence.

Remark 3. In the author’s view, artificial intelligence is a projection from human intelligence to machine intelligence. Projective geometry is an efficient method for dimensionality reduction. Artificial intelligence is based on composibility. It is assembled by many human and machine building blocks. This idea is consistent with the philosophy of twistor theory, as Penrose claims (2004, Chapter 33).

Remark 4. Metalogic geometry is an interesting and hopeful new approach. This paper just reported the first step on the road. The next topic is to project metalogic on the Riemann sphere of two-state systems (Penrose, 2004). Note that in metalogic, there is set of antipodals, such as provability verses unprovability, truth-value being true verses being false, validity verses invalidity, dependence verses independency, consistency verses inconsistency, and completeness verses incompleteness, etc. For each pair of antipodals, the north-pole and the south-pole are clear and the corresponding categories are well defined. The interesting topic is how to treat superposition states and self-referential statements. Note that the diameter connecting two poles is a line and in general it is a light-like straight line; namely, it is a twistor.

Remark 5. Integration science is a new advancement of cognitive science and it serves as the basic theoretical foundation for artificial intelligence. This paper opens a new direction along that line.

References

- Bailey, T. N. and Baston, R. J. (Eds.) (1990). Twisters in Mathematics and Physics. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Huggett, S. A. and Tod, K. P. (1985/1994). An Introduction to Twister Theory. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Margaris, A. (1967). First Order Mathematical Logic. Blaisdell Publishing Company.

- Penrose, R. (2004). The Road to Reality – A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Random House Inc., New York.

- Ward, R. S. and Wells JR, R. O. (1990). Twistor Geometry and field Theory. Cambridge University Press, New York.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).