1. Introduction

In educational environments, analyzing and predicting interactions between students and questions is essential for providing personalized learning experiences. With the proliferation of digital educational platforms and the accumulation of large-scale educational data, extracting meaningful insights from such data has become increasingly critical. In this context, Knowledge Tracing (KT) has established itself as a core methodology for modeling student-question interactions to predict learning performance. It serves as the foundation for intelligent tutoring systems to infer conceptual understanding and skill acquisition levels, enabling customized curricula delivery [

1].

The student responses observed in educational interactions represent more than superficial phenomena—they result from interactions between the `latent traits’ of both students and questions. These latent traits refer to internal state values that, while not directly observable, significantly influence entities’ observable behaviors. For students, latent traits can include knowledge state, conceptual understanding, problem-solving ability, learning style, and cognitive characteristics. For questions, latent traits can include difficulty, complexity, cognitive demand level, and required prerequisite knowledge.

However, existing KT approaches have limitations in comprehensively addressing the latent traits of both students and questions. To overcome these limitations, this study applies the Cyclic Dual Latent Discovery (CDLD) methodology [

2] to educational data. CDLD is a methodology that progressively discovers the comprehensive latent traits of users and items through cyclic learning between dual deep learning models. This is based on the premise that all interactions are manifestations of the underlying latent traits of the respective entities.

This study validates the applicability of the Cyclic Dual Latent Discovery (CDLD) methodology to the educational domain by applying it to the large-scale EdNet dataset [

3]. Our approach involves discovering the comprehensive latent traits of students and questions directly from their interaction data and subsequently utilizing these traits to predict learning outcomes. The experimental results demonstrate that this process is not only effective but also achieves competitive predictive performance relative to existing leading methods on this benchmark, highlighting the potential of comprehensive latent trait discovery.

2. Related Work

Traditional KT approaches are limited by their simplistic modeling techniques and their inability to effectively discover complex latent traits. Bayesian Knowledge Tracing (BKT) [

4] represents students’ knowledge states only as binary variables (’mastered’ or ’not mastered’), failing to capture comprehensive student latent traits beyond binary mastery states. Performance Factor Analysis (PFA) [

5], while improving predictive accuracy, primarily models student-question interactions through linear combinations of predefined parameters, thereby providing limited capacity to capture complex nonlinear relationships between comprehensive latent traits.

Deep learning-based approaches have demonstrated systematic progress in modeling educational interaction patterns, as evidenced by recent comprehensive analyses [

6]. Early architectures like Deep Knowledge Tracing (DKT) [

7] established the viability of recurrent neural networks for temporal sequence modeling. Subsequent developments introduced specialized components—Dynamic Key-Value Memory Networks (DKVMN) [

8] incorporated memory mechanisms for concept relationship tracking, while Self-Attentive Knowledge Tracing (SAKT) [

9] utilized transformer architectures to capture long-range dependencies. The SAINT [

10] and SAINT+ [

11] frameworks extended these foundations through encoder-decoder configurations.

Contemporary extensions address specific modeling challenges: DKVMN&MRI [

12] integrates exercise-knowledge relationships with forgetting curve dynamics, DyGKT [

13] employs continuous-time dynamic graphs to handle infinitely growing learning sequences, and AAKT [

14] reformulates knowledge tracing as a generative process using question-response alternate sequences. Despite architectural diversity, existing approaches model only partial aspects of student or question latent traits—such as knowledge states for students or difficulty levels for questions—rather than discovering comprehensive latent representations. They remain constrained to predefined latent traits instead of uncovering the comprehensive latent traits for each entity.

The Cyclic Dual Latent Discovery (CDLD) approach addresses this limitation by discovering comprehensive latent trait vectors for both students and questions through cyclic optimization. Unlike methods that predefine which traits to model, CDLD enables latent traits to emerge from interaction data, capturing the diverse factors that influence educational outcomes and providing a foundation for applications beyond performance prediction.

3. Proposed Method: CDLD Application for Latent Trait Discovery

This section details the CDLD methodology applied for predicting interactions in educational data. The user and item specified in the CDLD methodology correspond to student and question respectively in this study. Accordingly, unless otherwise noted, user refers to student and item refers to question.

3.1. Entity-Processor Perspective and Latent Trait Modeling

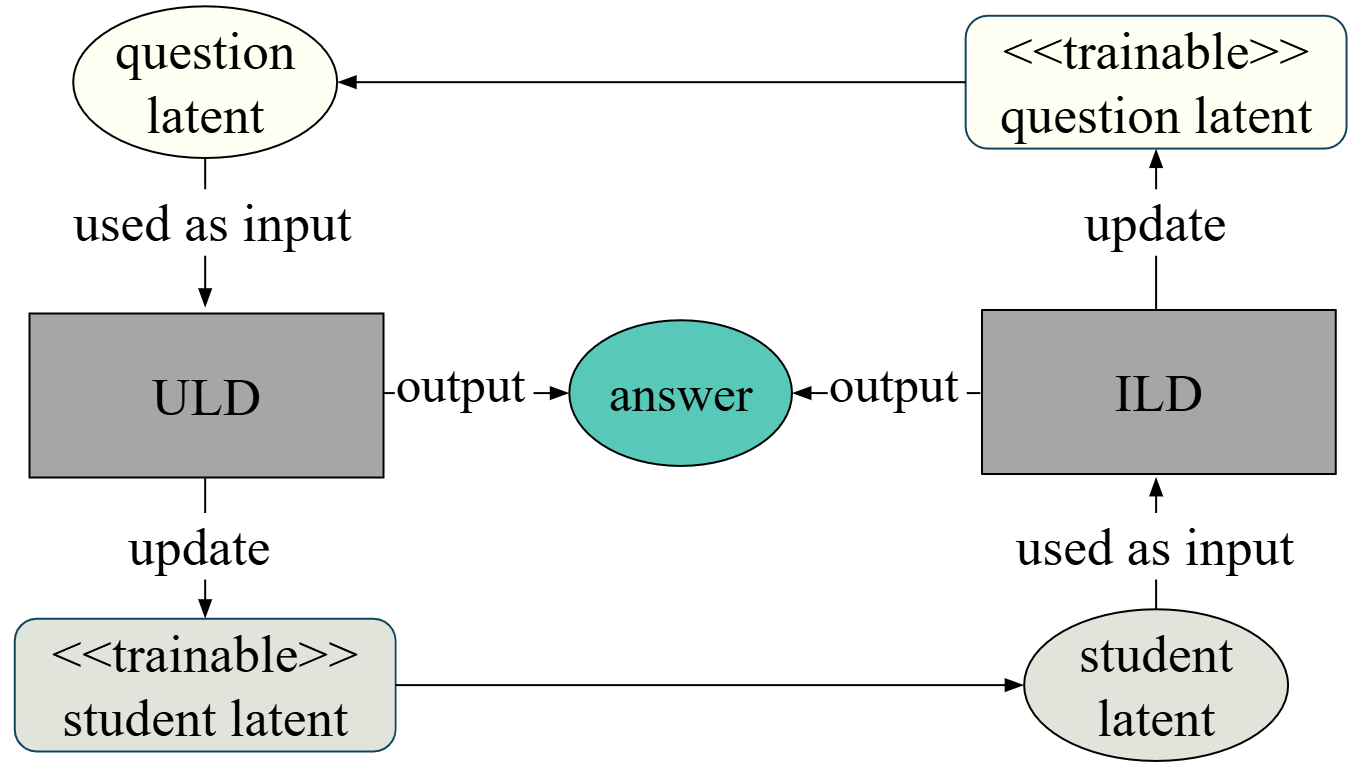

In educational interactions, students and questions interact as mutual processors rather than independent entities. A student’s latent academic ability and a problem’s latent difficulty influence each other, and the interaction between the two determines the resulting answer. From this perspective, a question can be regarded as a processor that receives a student entity as input and produces an answer that reflects the student’s academic ability. Similarly, a student can be viewed as a processor that receives a question entity and generates a answer that reflects the perceived difficulty of the question. This perspective, as illustrated in

Figure 1, suggests that the answer is the outcome of one entity processing the latent traits of the other.

Mathematically, the interaction result

between student

S and question

Q can be expressed as:

where

g denotes the interaction function, and

represents the noise term arising from inevitable variability and uncertainty in real-world educational settings. More specifically, this can be expressed as:

Existing educational data analysis approaches typically rely only on observable student features and question features to predict interaction results and either ignore or oversimplify student latent traits and question latent traits . In contrast, CDLD aims to directly discover the latent traits and from the interaction results .

Although not directly observable, the latent traits of users are underlying factors that significantly determine the outcomes of interactions. It’s very important for KT task. In CDLD, these latent traits are represented as a d-dimensional vector and , which is discovered through User Latent Discoverer (ULD) and Item Latent Discoverer (ILD) of CDLD.

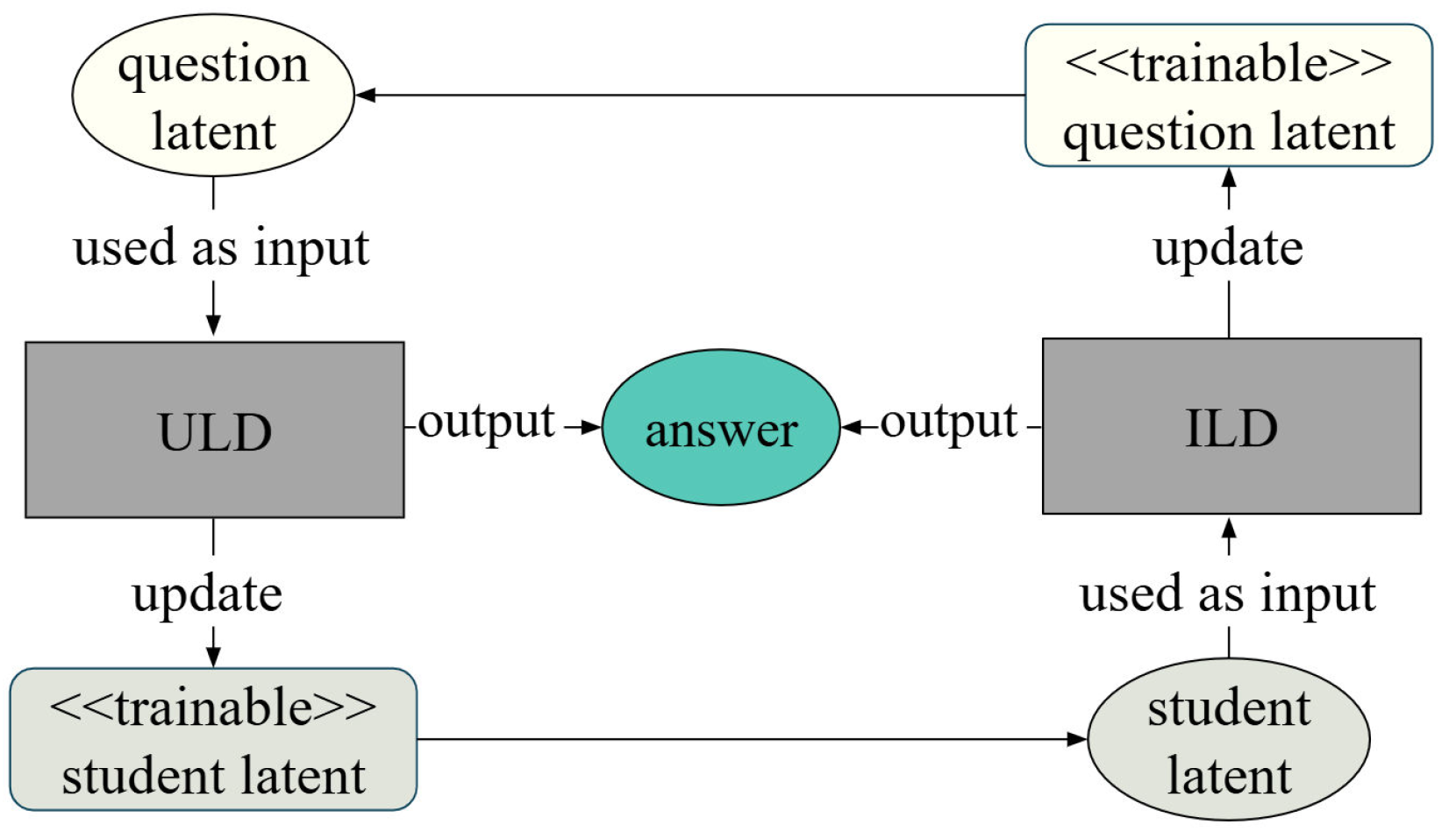

3.2. Cyclic Latent Trait Discovery Framework

ULD and ILD are deep neural networks (DNNs) that takes

,

,

, and

as input and output answer. ULD and ILD can be represented by Equations (

3) and (

4), respectively.

In contrast to conventional DNNs, where only the network parameters are updated during training, (

3) illustrates that CDLD updates both the parameters of the ULD network and the user’s latent traits. Similarly, in (

4), the item’s latent traits are updated along with the ILD network. In both equations, the asterisk (*) denotes components—whether parameters or latent inputs—that are updated during training.

First, ULD is trained while updating

, which is then used as a fixed input for training ILD. After ILD training is completed and

is updated, it is used as a fixed input for training ULD. By cyclic training ULD and ILD in this manner, the student latent traits and question latent traits are discovered. The training procedure described above is illustrated in Fig.

Figure 2.

4. Experiments

This section presents the experimental evaluation of the CDLD methodology on the EdNet dataset, aiming to discover and assess the latent traits of students and questions through answer prediction.

4.1. Data Preparation

EdNet is a student-system interaction dataset collected from the online educational platform Santa. We used EdNet-KT1, containing approximately 96.25 million response records from about 780,000 students and 13,000 questions. Each question includes features such as part (type), tags, and correct answers.

The dataset provides additional temporal and structural information including timestamps (when questions were given) and bundle ids (grouping questions that share common materials like passages or images). In this study, we utilized only the elapsed time information, which represents the time taken by students to answer each question. Since this dataset does not contain student features, we modified the original CDLD model to operate without them.

When students answered the same question multiple times, we retained only their latest response to capture their most recent knowledge state. To ensure sufficient data for meaningful latent trait discovery, we filtered the dataset to include only students and questions with at least three interactions each. This filtering process removed approximately 70,000 records, indicating that the vast majority of students and questions in our dataset already met the minimum interaction threshold. This preprocessing resulted in approximately 79.85 million interaction records.

The categorical features were processed using one-hot encoding for the part attribute and multi-hot encoding for the tags attribute. The target variable, indicating the correctness of student responses, was binarized, resulting in a label distribution where 68.9% of responses were correct. No class imbalance correction techniques were applied. To ensure randomized data distribution, the dataset was stratified and partitioned user-wise into training, validation, and test sets using an 8:1:1 ratio, where each user’s interactions were independently shuffled and split to maintain consistent proportions across individual user behavior patterns.

4.2. Baseline Methods

We compare our CDLD approach with the following knowledge tracing methods:

SAINT [

10]: A Transformer-based knowledge tracing model that features an encoder-decoder architecture where questions and responses are processed separately. The encoder applies self-attention layers to question embeddings, while the decoder alternately applies self-attention and encoder-decoder attention layers to response embeddings and encoder outputs.

SAINT+ [

11]: An enhanced version of SAINT that maintains the same encoder-decoder architecture while incorporating temporal features. Specifically, it integrates two temporal feature embeddings into response embeddings: elapsed time (time taken to answer) and lag time (time interval between adjacent learning activities).

PEBG+DKT [

15]: A method that pre-trains question embeddings by constructing a question-concept bipartite graph and exploiting question difficulty along with three types of relations (question-concept, inter-question similarities, and inter-concept similarities). The pre-trained embeddings are then integrated with Deep Knowledge Tracing for performance prediction.

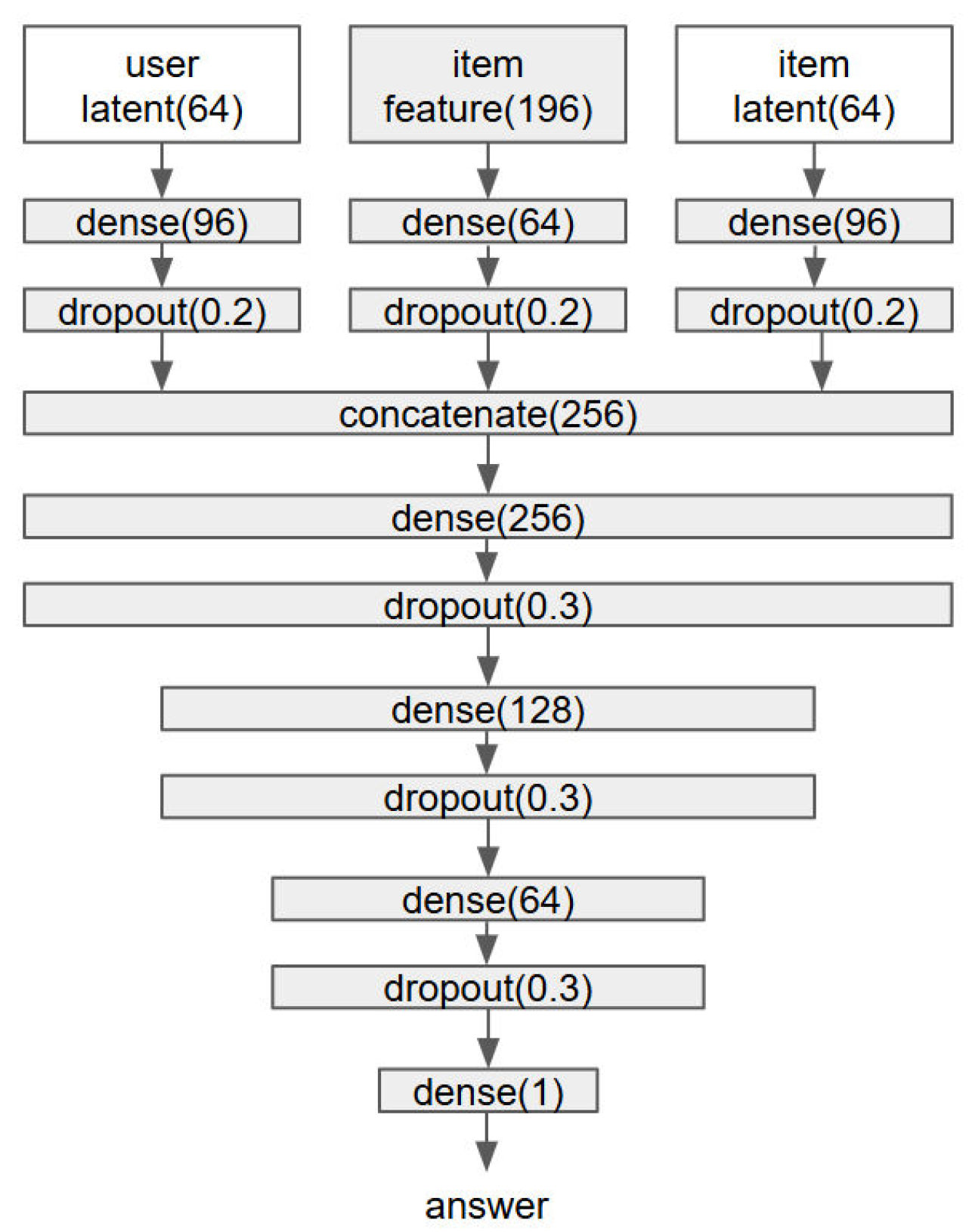

4.3. Model Architecture

Figure 3 illustrates the architectures of the ILD and ULD modules. Each dense layer employs the swish activation function, with the final layer using sigmoid. Notably, the item latent traits in ILD and the user latent traits in ULD are implemented as model layers rather than input variables, allowing them to be updated during training. The implementation follows the same methodology as the original CDLD framework. The predictor model, which shares the same architecture, uses fixed latent trait inputs without updates, consistent with standard deep neural network conventions. Additionally, in the predictor model, elapsed time is incorporated as an input feature, processed through a dense layer with 4 units before being concatenated with other features at the concatenate(256) layer.

4.4. Training Details

The dimensions of both user and item latent vectors were set to 64. The training followed a cyclic scheme in which ILD was trained for 5 epochs, followed by 5 epochs of ULD training; this alternating cycle was repeated 5 times, all conducted within a single Jupyter notebook session. After completing the cyclic training of ILD and ULD, the Predictor model was trained for 20 epochs using the learned latent representations. All training was conducted on Google Colab with L4 GPU using a batch size of (262,144).

For subsequent experiments (ablation studies and elapsed time feature exclusion), only the Predictor was retrained using the pre-trained latent representations from ILD and ULD. The Adam optimizer was used with an initial learning rate of , and learning rate scheduling was applied using ReduceLROnPlateau with validation AUC as the monitoring metric, which reduced the learning rate by 50% if validation performance did not improve for two consecutive epochs.

The model was trained using a composite loss function consisting of categorical cross-entropy combined with L2 regularization. We applied a weight decay coefficient of to all dense layer weights to prevent overfitting. We evaluated model performance using accuracy and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) as our primary metrics.

4.5. Experimental Results

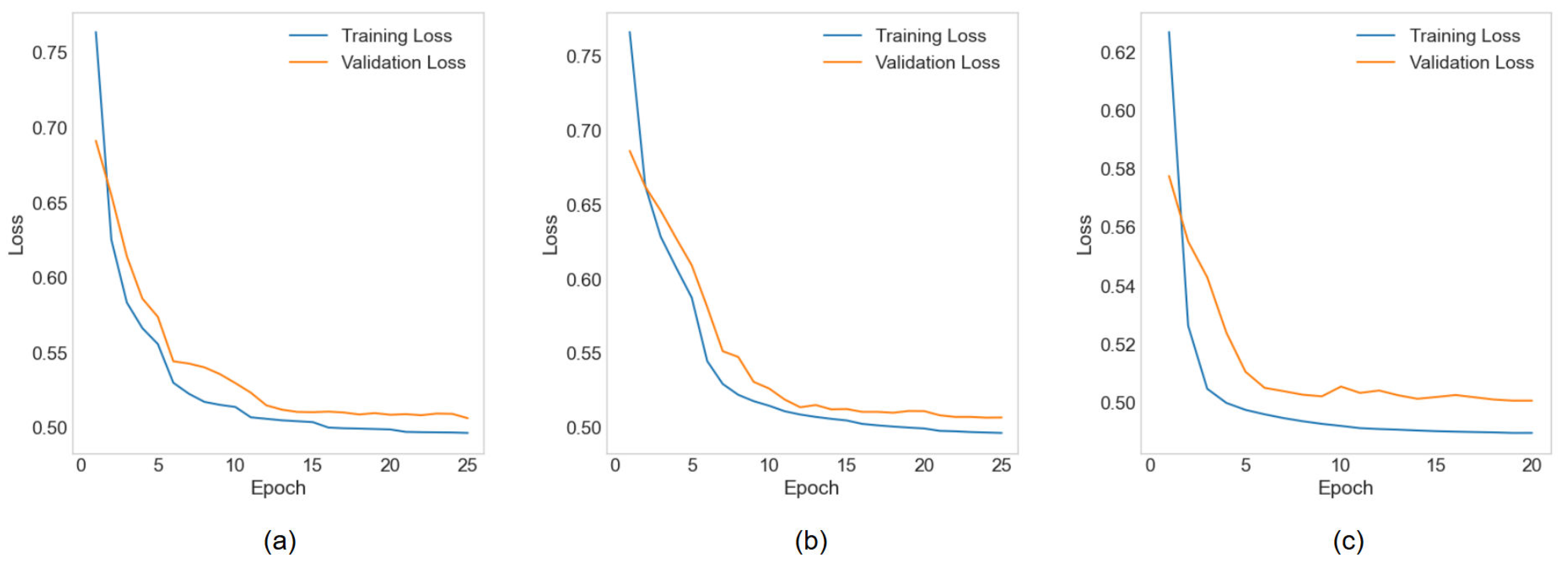

Figure 4 shows the loss graphs of ULD, ILD, and predictor training. All three models converged before 50 epochs.

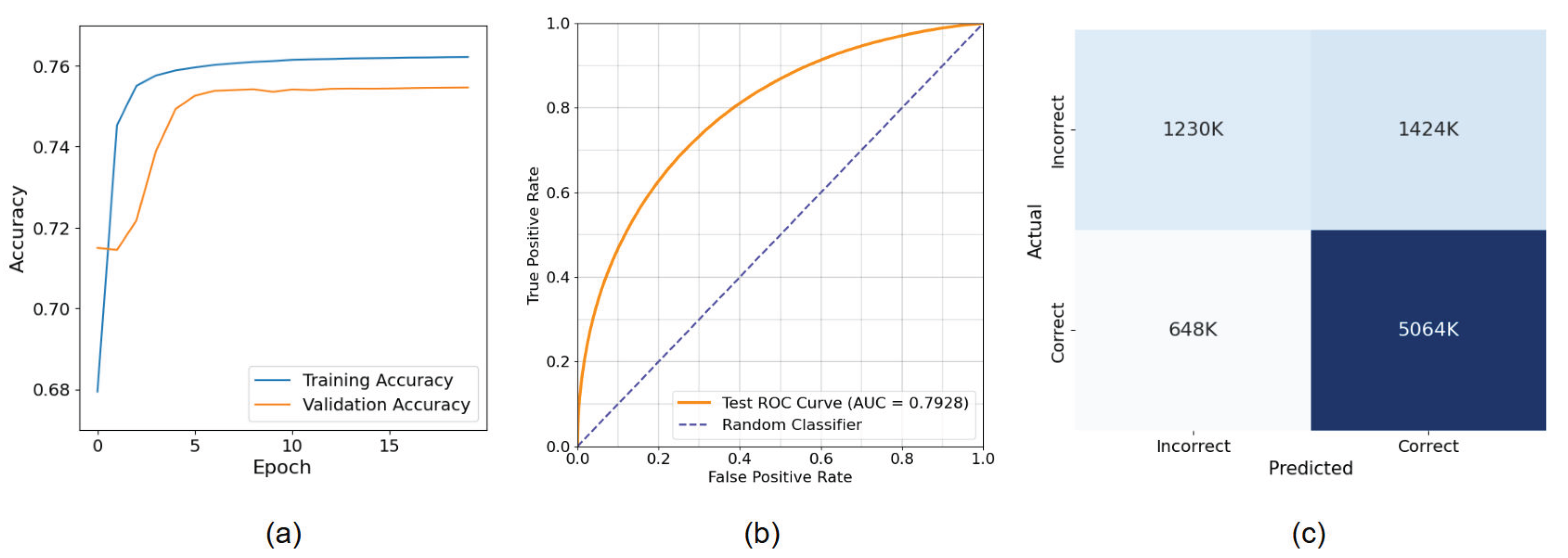

Figure 5 shows the accuracy graph during training, ROC curve, and confusion matrix.

4.5.1. Overall Performance

The CDLD model achieved competitive performance on the EdNet dataset. Our approach attained an AUC of 0.793 and accuracy of 0.752, with precision of 0.781 and recall of 0.887.

Table 1 presents a comparison with existing previous methods on the same dataset.

It should be noted that the differences in the number of students between SAINT and SAINT+ likely reflect variations in dataset versions. Additionally, each method employed different data splitting strategies: SAINT used a user-based split (train: 439,143 users, validation: 62,734 users, test: 125,470 users), while SAINT+ used the most recent 100K students as the test set with an 80%/20% split of the remaining data for training and validation. Our approach followed a stratified user-wise 8:1:1 split. While these methodological differences prevent perfectly controlled comparisons, CDLD demonstrates competitive performance relative to existing approaches.

4.5.2. Assessing of Latent Trait Informativeness

To assess the informativeness of the discovered latent traits, we conducted ablation experiments using only observable features, without latent traits. We used macro F1-score as our primary evaluation metric, which averages class-wise F1-scores and offers a balanced assessment under class imbalance. When using only observable features, the model achieved a macro F1-score of 0.481, indicating limited predictive power.

Table 2 shows the result. In contrast, when latent traits were incorporated, the model’s performance improved substantially. This suggests that the discovered latent traits encode meaningful information that is essential for accurate prediction. Furthermore, when using only latent traits and excluding the features, the accuracy degradation was only 1%. This finding indicates that the latent traits discovered through entity interactions carry more predictive information than the observable features themselves.

4.5.3. Impact of Elapsed Time Feature

To evaluate the contribution of temporal information to model performance, we conducted experiments comparing CDLD models with and without elapsed time features. The elapsed time feature represents the duration taken by students to complete each question, which captures temporal patterns in learning behaviors. While the original CDLD experiments incorporated this temporal information, we present a comparative analysis excluding this feature to isolate the impact of purely latent trait-based learning.

Table 3 presents the comparative results, showing that the inclusion of elapsed time features leads to consistent improvements across all evaluation metrics. Although the improvements are modest, they demonstrate that temporal patterns in student responses provide complementary information to the latent traits discovered through CDLD, suggesting that time-based behavioral indicators enhance the model’s ability to diagnose learning states.

5. Discussion

5.1. Educational Applications

The latent traits discovered through CDLD may offer potential benefits for various educational applications. One such possibility is student grouping, in which clustering algorithms could be applied to latent trait representations to identify students with similar learning profiles. This information may assist educators in developing customized learning paths tailored to the characteristics of each group. For example, students exhibiting lower values in certain latent dimensions might benefit from targeted reinforcement materials addressing those specific areas.

Another potential application lies in question analysis and curriculum design. The latent traits associated with questions may offer insights into their inherent difficulty and structural characteristics. When certain latent trait patterns are consistently associated with low accuracy rates, these patterns could serve as indicators of question difficulty. Additionally, by applying distance metrics such as Euclidean or cosine similarity in the latent space, it may be possible to identify questions with similar attributes, thereby supporting the construction of balanced assessments and targeted practice sets.

A particularly promising direction is the development of recommendation systems that utilize both student and question latent traits derived from CDLD. Such systems could recommend questions that align with a student’s current proficiency—those with high predicted success rates may help maintain engagement, while questions within the learner’s zone of proximal development could enhance learning effectiveness. This personalized selection mechanism offers a meaningful alternative to traditional one-size-fits-all educational approaches. Collectively, these potential applications suggest that CDLD can function not only as a predictive model but also as a general framework for data-driven decision-making in educational settings.

5.2. Limitations

While our approach demonstrates superior performance on the EdNet dataset, several limitations should be acknowledged. The evaluation was conducted using a single educational dataset focused on English language learning. Therefore, it remains important to validate the approach across diverse educational domains such as mathematics, science, and other subjects to establish broader generalizability.

A notable challenge of the proposed approach lies in the interpretability of the discovered latent traits. Although these traits are encoded as 64-dimensional vectors, the dimensions are entangled and lack explicit correspondence to interpretable educational concepts. This entanglement hinders the ability to provide educators with intuitive explanations regarding the meaning of each latent dimension or its relationship to observable student attributes and question features. The abstract nature of these representations may constrain their practical applicability in educational contexts where clear and actionable insights are required by stakeholders.

Furthermore, the current CDLD model treats each student–question interaction as independent, thereby failing to capture the temporal dynamics inherent in learning processes. Although students’ knowledge states evolve over time, the model does not consider sequential patterns or learning trajectories. This static method may overlook important information regarding the progression of student ability and the influence of prior interactions on subsequent performance.

5.3. Future Work

Building on our findings and addressing the identified limitations, several promising directions for future research emerge. To enhance the interpretability of latent traits, future work should develop methods for analyzing correlations between specific latent dimensions and observable features such as student achievement levels or question difficulty ratings. Dimensionality reduction techniques and feature selection methods could help identify more interpretable latent representations.

Incorporating temporal modeling represents another crucial research direction. Integrating CDLD with sequence modeling techniques such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or transformer architectures could capture the evolving nature of student knowledge. Such temporal extensions would enable the model to consider learning trajectories, identify knowledge retention patterns, and predict long-term learning outcomes more accurately.

Domain generalization and practical deployment warrant further investigation. While the results on English language learning data are encouraging, validation across diverse educational domains—such as mathematics, science, and the humanities—is necessary. Each domain may present unique interaction patterns and require domain-specific adaptations of the CDLD framework. In addition, user studies involving educators and students could offer valuable insights into the effective use of latent trait information in classroom settings. Such studies should evaluate the practical benefits of CDLD-based recommendations, the usability of latent trait visualizations, and their overall impact on learning outcomes.

6. Conclusion

We successfully applied CDLD to the EdNet educational dataset to discover the latent traits of students and questions and to predict question responses. CDLD achieved an AUC of 0.793, indicating meaningful predictive performance. An ablation study was conducted to assess the informativeness of the discovered traits. These results suggest the potential utility of CDLD for various educational applications.

Author Contributions

G.Y. conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. D.R. conceived the study, supervised the research, and contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The EdNet dataset used in this study is publicly available from the Riiid organization (

https://github.com/riiid/ednet). The processed dataset and code used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ding X, Larson EC (2021) On the interpretability of deep learning based models for knowledge tracing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.11335. [CrossRef]

- Rim D, Nuriev S, Hong Y (2025) Cyclic Training of Dual Deep Neural Networks for Discovering User and Item Latent Traits in Recommendation Systems. IEEE Access 13:10663–10677. [CrossRef]

- Choi Y, Lee Y, Shin D, Cho J, Park S, Lee S, Baek J, Bae C, Kim B, Heo J (2020) EdNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Dataset in Education. In: Bittencourt I, Cukurova M, Muldner K, Luckin R, Millán E (eds) Artificial Intelligence in Education. AIED 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 12164. Springer, Cham, pp 69–73. [CrossRef]

- Corbett AT, Anderson JR (1994) Knowledge tracing: Modeling the acquisition of procedural knowledge. User Model User-Adapt Interact 4(4):253–278. [CrossRef]

- Pavlik PI, Cen H, Koedinger KR (2009) Performance factors analysis–a new alternative to knowledge tracing. In: Proc Artif Intell in Education, pp 531–538. [CrossRef]

- Shen S, Liu Q, Huang Z, Zheng Y, Yin M, Wang M, Chen E (2024) A Survey of Knowledge Tracing: Models, Variants, and Applications. IEEE Trans Learn Technol 17:1858–1879. [CrossRef]

- Piech C, Bassen J, Huang J, Ganguli S, Sahami M, Guibas LJ, Sohl-Dickstein J (2015) Deep knowledge tracing. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, Canada, pp 505–513.

- Zhang J, Shi X, King I, Yeung DY (2017) Dynamic key-value memory networks for knowledge tracing. In: Proc 26th Int Conf World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, pp 765–774. [CrossRef]

- Pandey S, Karypis G (2019) A self-attentive model for knowledge tracing. In: Proc 12th Int Conf Educational Data Mining, Montreal, Canada, pp 384–389. [CrossRef]

- Choi Y, Lee Y, Cho J, Baek J, Kim B, Cha Y, Shin D, Bae C, Heo J (2020) Towards an appropriate query, key, and value computation for knowledge tracing. In: Proc 7th ACM Conf Learning@Scale, Virtual Conference, pp 341–344. [CrossRef]

- Shin D, Shim Y, Yu H, Lee S, Kim B, Choi Y (2021) Saint+: Integrating temporal features for ednet correctness prediction. In: Proc 11th Int Learn Analytics and Knowl Conf, Virtual Conference, pp 490–496. [CrossRef]

- Xu F, Huang J, Lv M, Deng S, Liu H, Yang Y (2024) DKVMN&MRI: A new deep knowledge tracing model based on DKVMN incorporating multi-relational information. PLoS One 19(10):e0312022. [CrossRef]

- Cheng K, Peng L, Wang P, Ye J, Sun L, Du B (2024) DyGKT: Dynamic Graph Learning for Knowledge Tracing. In: Proc 30th ACM SIGKDD Conf Knowl Discovery Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, pp 409–420. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Rong W, Zhang J, Sun Q, Ouyang Y, Xiong Z (2025) AAKT: Enhancing Knowledge Tracing With Alternate Autoregressive Modeling. IEEE Trans Learn Technol 18:25–38. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Yang Y, Chen X, Shen J, Zhang H, Yu Y (2020) Improving Knowledge Tracing via Pre-training Question Embeddings. In: Proc 29th Int Joint Conf Artificial Intelligence, pp 1577–1583. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).