1. Introduction

Argentina ranks globally as the third-largest honey producer and the second-largest exporter, with an annual average production of 70,000 tons of honey [

1]. This international trade generates significant economic impacts at both regional and national levels [

2]. However, the close relationship between supply and demand has substantial environmental consequences for the producing country. Like other sectors of the food industry [

3], this activity requires a large amount of water, as it is used throughout most plant operations. This is directly related to an increase in the grey water footprint, primarily linked to effluent generation throughout the supply chain [

4].

As a result of honey processing, organic effluents are generated, consisting mainly of honey residues, external contaminants (dust particles, soil, etc.) from drums to transport honey from the field to the fractionation plant and by-products of cleaning activities of the plant. The high levels of Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), together with the low pH levels in the wastewater resulting from the cleaning of drums and the floors of the fractionation plant, require treatment prior to its discharge or infiltration into the ground. Currently, the available information on the management of this type of wastewater is limited, and the literature does not describe applicable in situ biological treatments. In practice, various approaches persist, ranging from highly hazardous and polluting methods (such as the direct discharge of these effluents without prior treatment) to unsustainable strategies, such as outsourced treatment, in which the waste is transported and treated ex situ using conventional technologies. Although this latter alternative ensures a certain level of treatment, it entails significant increases in operational costs and environmental impacts, mainly associated with the carbon footprint generated by the transportation and external processing of the effluents.

Bee honey is known not only for its nutritional and therapeutic properties for humans [

5,

6], but also for its bactericidal potential, attributed to various factors such as its low pH, high sugar concentration, generation of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), presence of antimicrobial peptides, and low nitrogen and phosphorus content [

7]. These characteristics confer a high level of complexity to the effluent, that significantly limits the applicability of the conventional biological treatment systems, as only a few microorganisms can thrive under these conditions [

7]. Therefore, to achieve effective biological treatment, it is essential to select microbial strains adapted and highly tolerant to such complex matrices.

In this context, the identification of organisms present in the effluent is the first step in finding a solution to its treatment. Subsequently, studying the bioremediation potential of these organisms will support the development of alternative biological treatments for effluents from honey processing facilities.

In a previous research, a non-Saccharomyces yeast strain, identified as strain H3 of

Candida ethanolica, was isolated from an industrial effluent from Argentine exporting company [

8]. The bioremediation potential of strain H3 was evaluated positioning this yeast strain as a promising candidate for the treatment of wastewater from the beekeeping industry. However, due to the high COD concentrations in these effluents, integrated bioremediation approaches are required, combining different microorganisms with complementary metabolic capabilities [

8].

In this sense, microalgae have been extensively described as bioremediation agents for effluents with organic and inorganic contamination [

9].

Chlorella vulgaris, in particular, is one of the most commonly used species in bioremediation [

10,

11], due to its ability to adapt to various types of effluents and remove nutrients, heavy metals, and organic matter, among other pollutants [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Recent studies have explored the synergy between microalgae and heterotrophic microorganisms, such as yeasts, in co-culture systems for bioremediation [

16,

17]. Through their metabolism, yeasts transform complex sugars and other organic compounds into simpler and less toxic substances than can be assimilated by other organisms, such as microalgae, in later treatment stages or in combined systems [

18]. This approach offers several advantages: i) mixed microbial cultures reflect dynamics typical of natural ecological systems; ii) nutrients and metabolite exchange between species enhances co-culture stability and resilience; iii) it facilitates biomass harvesting; and iv) functional metabolite production, such as lipids, is enhanced through microbial interactions, contributing to waste valorization [

16,

19,

20]. Furthermore, the co-utilization of microalgae and heterotrophic microorganisms has been shown to improve the overall efficiency of wastewater treatment [

21].

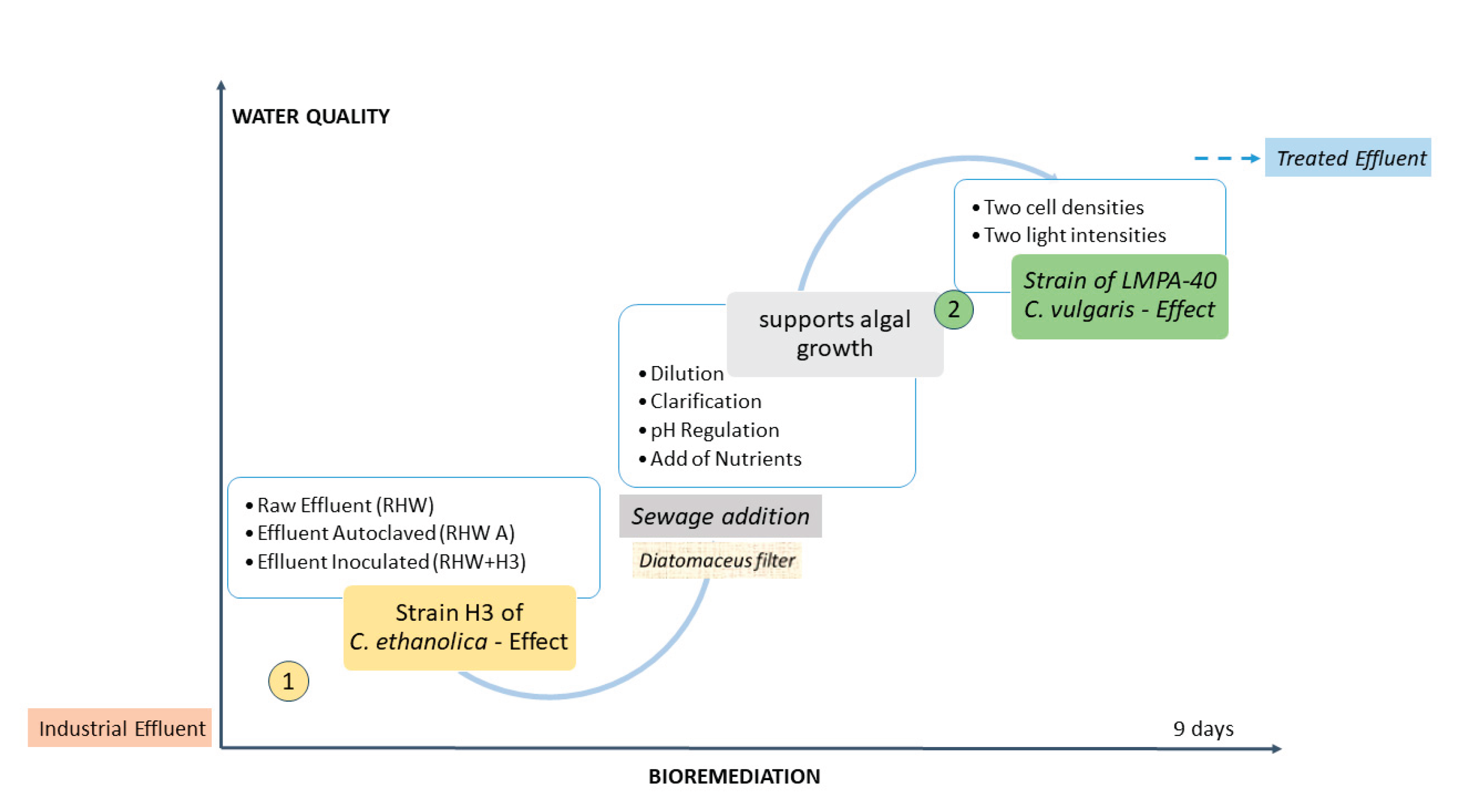

The present study was conducted to develop a sequential biological treatment that integrates two complementary bioprocesses. In the first stage, the strategy of using the native non-Saccharomyces yeast strain H3 of C. ethanolica isolated and inoculated in the industrial effluent for its initial conditioning is resumed. In the second stage, the microalga C. vulgaris is incorporated together with a second effluent generated in the administrative sector of the company (quite similar to domestic wastewater), which supports algal growth and completes the treatment. This strategy not only optimizes pollutant load reduction but also represents a novel, environmentally sustainable, and economically viable in situ alternative for the integral management of all liquid waste generated by the beekeeping industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wastewater Samples and Microorganisms

2.1.1. Industrial Effluent

Effluent generation during the processing and conditioning of honey for export is associated with the following main stages of the process: i) Reception: external washing of drums from beekeepers and collectors, ii) Sampling, and iii) Homogenization: in both stages, tools, equipment and facilities are cleaned. These liquid wastes present mixed contamination, with a predominant organic load from honey residues, along with a variety of substances such as dust, soil particles, and cleaning products. Honey residual wastewater (RHW) is collected through a drainage system and conveyed via pipes to a 15 m

3 storage tank located outside the facility (

Table 1). There it is stored until its final disposal via ex-situ treatment. RHW samples were obtained from this tank at a honey processing and exporting plant located in the Canning District, Buenos Aires Province –Argentina, between September 2022 and July 2023.

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters of residual honey water (RHW) and sewage effluent (RTW) at the beginning of the assay.

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters of residual honey water (RHW) and sewage effluent (RTW) at the beginning of the assay.

| |

Untreatment |

| Parameter |

RHW |

RTW |

| pH |

4.33 ± 0.03 |

6.57 ± 0.16 |

| COD (mg O2/L) |

27167 ± 192 |

731 ± 33 |

| Total sugar (mg/L) |

3690 ± 275 |

10 ± 0.02 |

| NH4 -N (mg/L) |

0.02 ± 0.00 |

32.9 ± 2.8 |

| Soluble reactive phosphorous (mg/L) |

0.03 ± 0.00 |

2.50 ± 0.39 |

2.1.2. Sewage Effluent

The administrative activities of the company generate grey and black water with characteristics similar to domestic wastewater (RTW), originating from bathrooms and changing rooms, kitchen and dining area (

Table 1). These effluents are collected in a septic tank and discharged without treatment into a sewage network that ends in soil absorption. RTW samples were collected directly from this septic tank belonging to the same company. The collection of RHW and RTW samples was conducted following appropriate biosafety standards.

2.1.3. Microbial Strains and Their Maintenance

C. ethanolica strain H3 was isolated from RHW by our team during the initial phase of this research line [

8]. This strain presents natural adaptation to the complex environmental conditions of this industrial effluent and has demonstrated high bioremediation potential [

8]. The strain was deposited and registered under code CoMIM4426 in the genetic bank of the National Institute of Agriculture Technology (INTA) – Mendoza – San Juan, Argentina. It was maintained in 50 mL of Yeast Extract Beef (YEB) medium in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks at 28°±2°C in a rotary shaker at 100 rpm. The composition of the YEB medium is as follows (g/L): Meat (Beef) Extract (5.00), Yeast Extract (1.00); Peptone from Meat (5.00), Sucrose (5.00), Magnesium Sulphate Anhydrous (0.24).

C. vulgaris native strain LMPA-40 (National Biological Data System, SNDB-173) was obtained from the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the National University of Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Argentina. It was maintained in 50 mL of synthetic wastewater medium (WS) [

22], in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. The cultures were incubated at 24°±2°C in a rotary shaker at 100 rpm under a 16 h PAR photoperiod (14 000 kJ, 400 μmol photon / m

2 s). The composition of the WS medium is as follows (mg/L): CH

3COONH

3 (240.88), KH

2PO

4 (43.94), NaHCO

3 (125.00), CaCl

2 (10.00), FeCl

2 (0.375), MnSO

4(0.038), ZnSO

4 (0.035), MgSO

4 (25.00), Yeast extract (50.00).

2.2. Experimental Design and Measurements

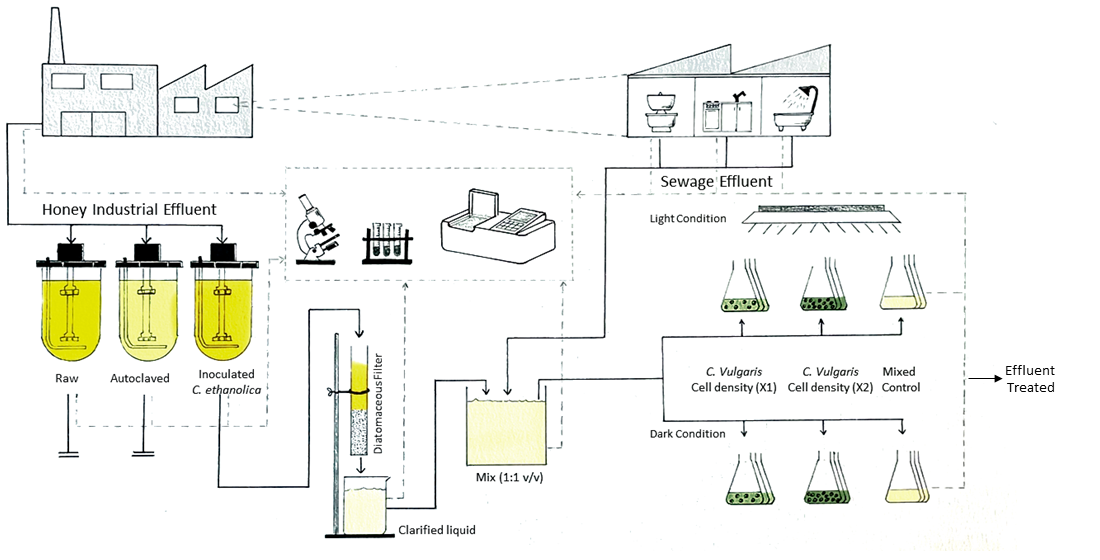

Figure 1 shows the schematic representation of the strategy used for the bioremediation of wastewater from the honey processing industry, using a dual-microorganism approach (

C. ethanolica and

C. vulgaris) in an integrated bioprocess.

The first stage was conducted in a stirred tank bioreactor (Minifors, Infors,

® Switzerland) with a working volume of 1.5 L. The non-aerated bioreactor was equipped with mechanical agitation provided by a marine propeller at 50 rpm. The temperature was maintained at 28±2 °C [

23]. Three treatments were applied: raw effluent RHW; autoclaved RHW (Arcano 80 L

® Chamberland) at 0.1 MPa for 20 minutes (RHW A); and RHW inoculated with H3 strain (2% v/v, DO 600 nm: 1.36±0.02) (RHW+H3). After 5 days, a filtration process was conducted using a column (238 cm

3) with diatomaceous earth under gravity flow obtaining a filtered effluent (RHWF). The RHWF was collected and mixed with a sewage effluent (RTW) in 1:1 ratio (v/v), adjusting the pH adjusted to 7.00 with 1N NaOH and called as RW.

The second stage involved a factorial experimental design with two factors for 4 days (

Figure 1). The first factor was cell density, evaluated at two levels. RW was inoculated with

C. vulgaris to achieve the following initial concentrations:

X1: 2.78x105cells/ mL

X2: 3.97x105cells/ mL

The second factor was light intensity, also at two levels. Both conditions maintained a photoperiod of 16 hours.

High light intensity (*): culture under high PAR intensity (14,000k, 400 μmol photon/ m2 s).

Low light intensity: culture under low PAR intensity (14,000k, 100 μmol photon/ m2 s).

A control treatment was also included, consisting of RW without C. vulgaris inoculation, cultured under high PAR intensity (14,000k, 400 μmol photon/ m2 s).

All treatments with microalgae were carried out in Erlenmeyer flasks (50 ml working volume; 250 ml total volume), incubated at 24±2 °C on an orbital shaker at 100 rpm.

2.3. Analytical Methods

Cell density (DO) for Candida ethanolica H3 was measured at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV-mini 1240, Shimadzu ®). C. vulgaris cell number was determined by counting in a Neubauer chamber.

Kinetic cell growth was estimated using the formula:

where X represents the biomass obtained at time (t), and μ is the specific growth rate.

The duplication time was calculated as:

The concentration of monosaccharides (glucose and fructose), sucrose and total sugar (glucose, fructose, sucrose) in the culture medium were determined using the colorimetric phenol-sulphuric acid method, as described in [

24,

25], with glucose, fructose and sucrose (Sigma) as the standards.

The Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), soluble reactive phosphorous (SRP) and ammoniacal Nitrogen (N-NH

4) were determined according [

26].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analytical determinations were carried out in triplicate. Results were evaluated by ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons, or by Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables, using Infostat software [

27,

28].

3. Results and Discussion

Honey is composed of approximately 80% carbohydrates, of which 75% corresponds to glucose and fructose, followed by sucrose, which accounts for less than 5%. In the residual honey effluent, both the content and proportions of these sugars are altered. These modifications are attributed to several factors such as dilution (estimated at approximately 100-fold), the incorporation of other residues present on the surface of honey drums, and the contribution of by-products derived from equipment and facility cleaning activities [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. The mixture of these substances, together with the prolonged storage of the effluent prior to final disposal, generates a synergistic effect that promotes microbial metabolic activity, leading to increased biomass and elevated COD levels that 40 times higher than the discharge limits established by the local environmental authority (700 mg O₂ /L, ADA Res. 336/03).This effluent is characterized not only by its high total sugar content, but also by low pH, and marked deficiency of essential macronutrients, primarily soluble reactive phosphorus and ammonium nitrogen (

Table 1).

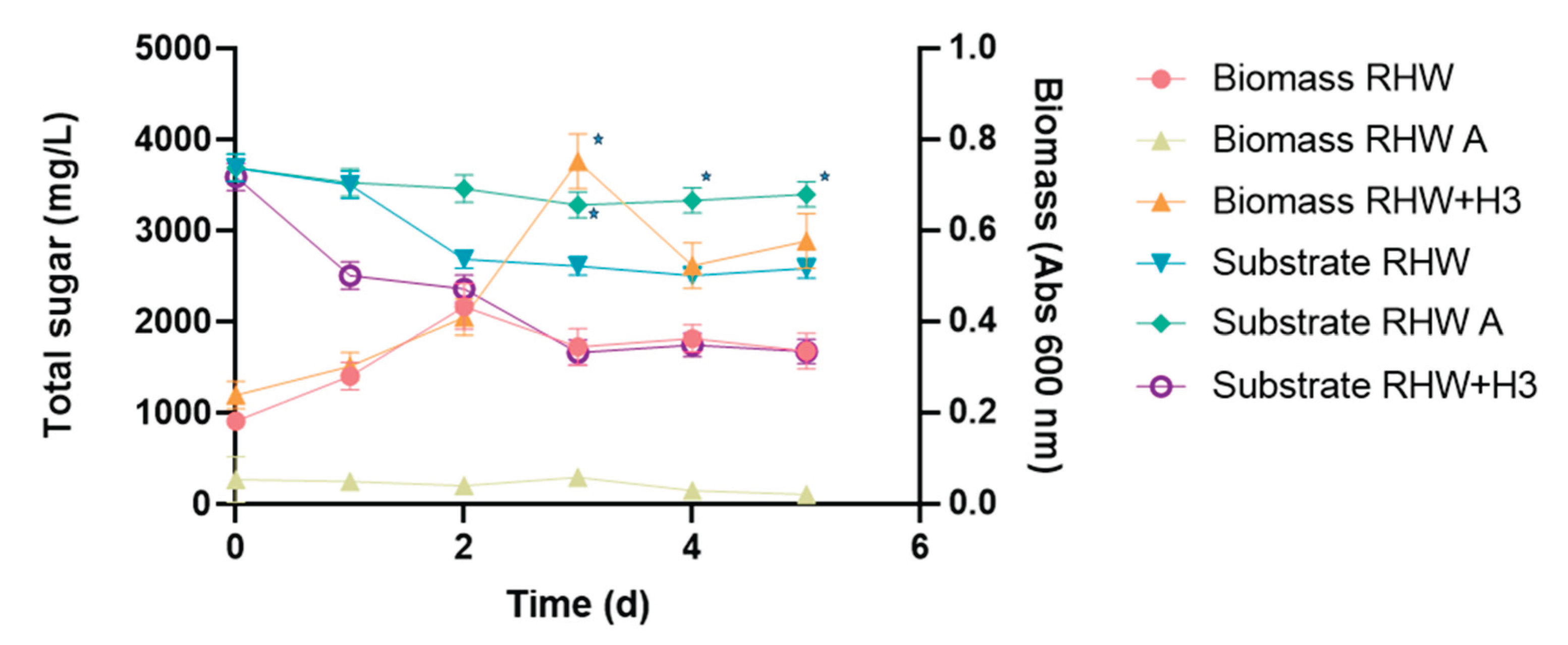

3.1. Yeast Treatment

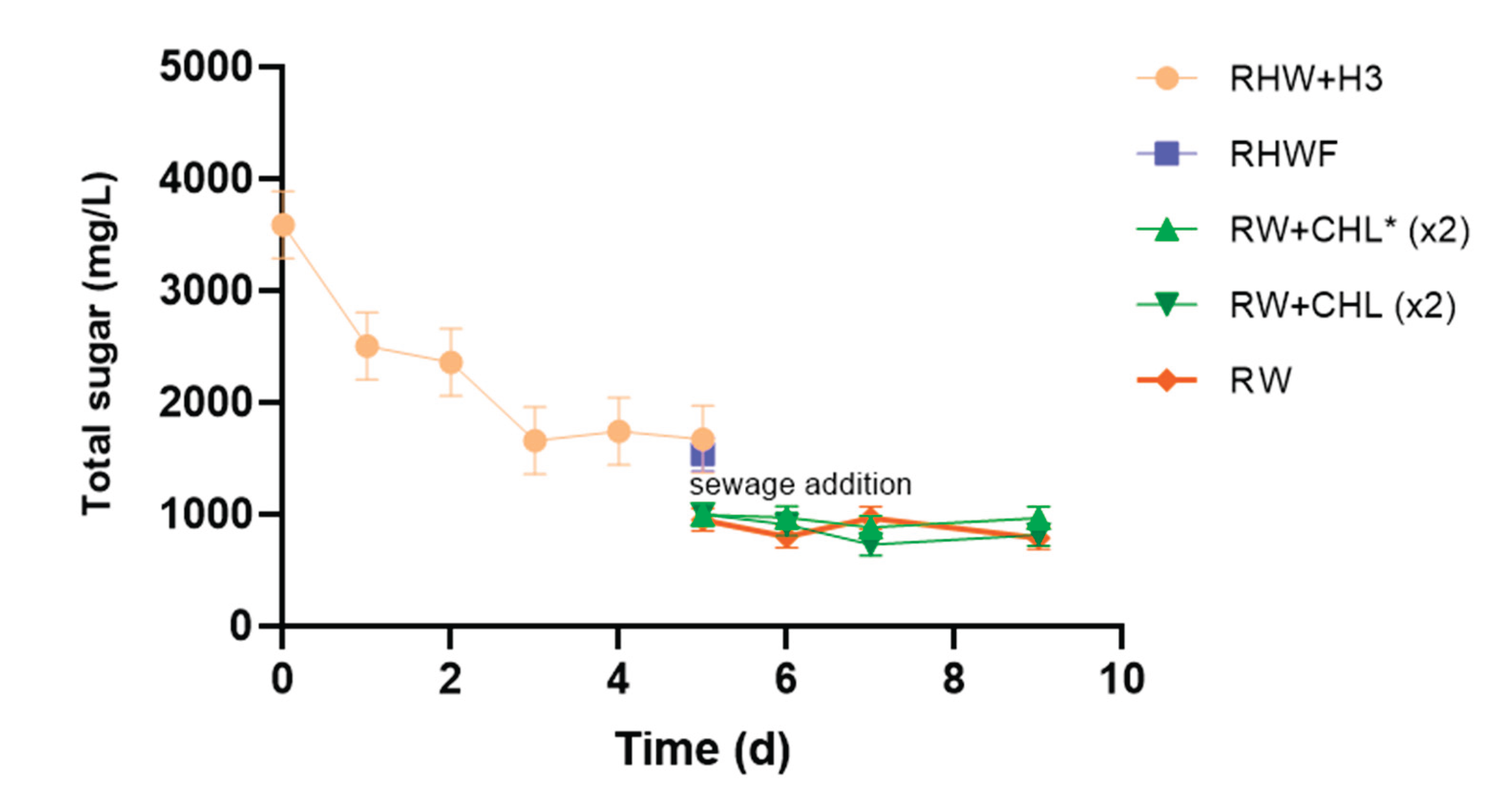

During RHW treatment, an increase in biomass corresponding to the native microflora was observed, along with 30% reduction in total sugar, composed of approximately 42% monosaccharides and 58% sucrose (

Figure 2). In environments with an excess of carbon sources such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose, yeasts are capable of rapidly hydrolyzing these compounds into simpler forms [

29,

34]. Furthermore, the native microbiota of the effluent can metabolize these compounds as nutrients through high- or low-affinity transport systems, enhancing the overall efficiency of the process [

18,

34]. In contrast, the axenic effluent RHW A, free of native microbiota, showed neither yeast growth nor significant substrate utilization, with only an 8% reduction in total sugar observed (

Figure 2).

The assays conducted during this treatment stage confirmed the positive effect of the

C. ethanolica H3 strain on total sugar reduction. The effluent inoculated with this yeast at 2% v/v RHW+H3 showed a significant increase in cell growth, reaching a total sugar removal efficiency nearly doubling that observed with the native microflora treatment (RHW) (

Figure 2). The RHW+H3 system exhibited a typical batch culture growth curve, with substrate (total sugar) consumption associated with the exponential growth phase, which peaked on day 3, followed by a decline phase as shown in

Figure 2. The kinetic parameters obtained included a specific growth rate (µ) of 0.607 d⁻¹ and a doubling time of 1.14 d. During this growth phase, 53% of the total sugar was consumed within three days (

Figure 2). At the end of the RHW+H3 treatment, the pH decreased to 3.96 ± 0.06, while COD increased by 8.7% compared to the initial value (

Table 1 and

Table 2). The COD slight increase could be attributed to oxygen consumption as well as the synthesis, accumulation, and availability of new organic compounds in the aqueous matrix and suspended biomass [

35].

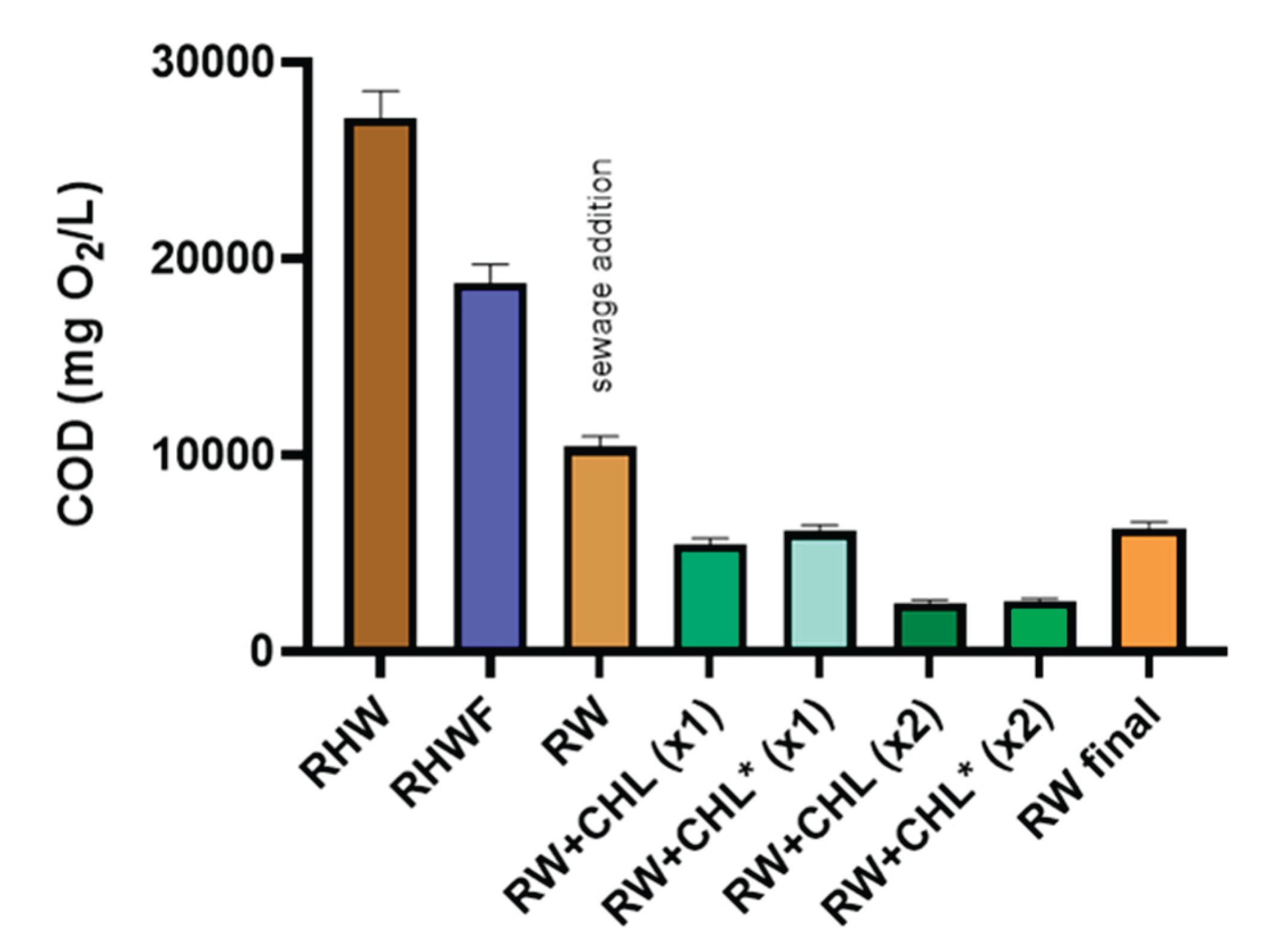

The effluent treated in RHW+H3 was filtered through a diatomaceous earth column to obtain RHWF. This filtering medium is an inert, naturally derived material composed of rigid, highly porous, and morphologically diverse nanostructures, making it an efficient and environmentally friendly alternative for industrial filtration system [

36,

37]. Clarification using this technique achieved a 91.6% reduction in turbidity, resulting in a 30.9% decrease in COD (

Figure 3,

Table 2). Additionally, during the filtration process, the intermittent vertical flow system not only functioned as a physical barrier for the removal of suspended solids and microorganisms, but it may also have induced an increase in dissolved oxygen in the filtered water, improving the oxidative conditions of the system [

38]. The total residence time for the RHW+H3 treatment, considering both substrates consumption and the filtration process, was five days.

Figure 3.

COD levels (mg O2/L) during an 9-day integrated bioprocess using C. ethanolica and C. vulgaris for honey industry effluent remediation in different stages of the treatment sequence. RHW: Residual honey water; RHWF: Filtered residual honey water; RW: RHWF mixed with septic tank effluent (RTW) in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio; RW+CHL (X1): C. vulgaris at low light condition, standard inoculum density; RW+CHL* (X2): C. vulgaris at high light condition, double inoculum density; RW+CHL (X2): C. vulgaris at low light condition, double inoculum density; CTRL: Control treatment containing RW. Note: CHL* denotes high light condition, while CHL indicates low light condition. Bars show s.d. of triplicated samples.

Figure 3.

COD levels (mg O2/L) during an 9-day integrated bioprocess using C. ethanolica and C. vulgaris for honey industry effluent remediation in different stages of the treatment sequence. RHW: Residual honey water; RHWF: Filtered residual honey water; RW: RHWF mixed with septic tank effluent (RTW) in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio; RW+CHL (X1): C. vulgaris at low light condition, standard inoculum density; RW+CHL* (X2): C. vulgaris at high light condition, double inoculum density; RW+CHL (X2): C. vulgaris at low light condition, double inoculum density; CTRL: Control treatment containing RW. Note: CHL* denotes high light condition, while CHL indicates low light condition. Bars show s.d. of triplicated samples.

3.2. C. vulgaris Treatment

The deficiency of essential macronutrients, primarily soluble reactive phosphorus and ammonium nitrogen and low pH of RHWF create hostile environmental conditions under which the growth of the LMPA-40 strain of

C. vulgaris can be significantly inhibited during the initial treatment stage, according to previous experiments (data not shown). The incorporation of RTW to RHWF as a second source of organic nutrients enriched the previously clarified effluent with essential nutrients during the initial treatment stage, enabling the complete replacement of the chemical additives commonly used in microalgae cultivation. This step was therefore fundamental to achieving the ecological sustainability and technological feasibility of the process.

Table 2 shows the nutrient contribution of RTW, which helped created favorable conditions for the development of microalgae and other beneficial microorganisms involved in the following treatment stage [

39,

40,

41]. Moreover, the mixture of these two liquid wastes (RHWF:RTW) not only served as a critical nutrient source but also contributed to pH regulation and dilution of the contaminant load of the effluent (RW). The dilution effect was evidenced by 44.4% decrease in COD and a 38.1% reduction in total sugar (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4;

Table 2). This contributed to an accumulated COD removal of 61.6% at this stage of the treatment (

Figure 3).

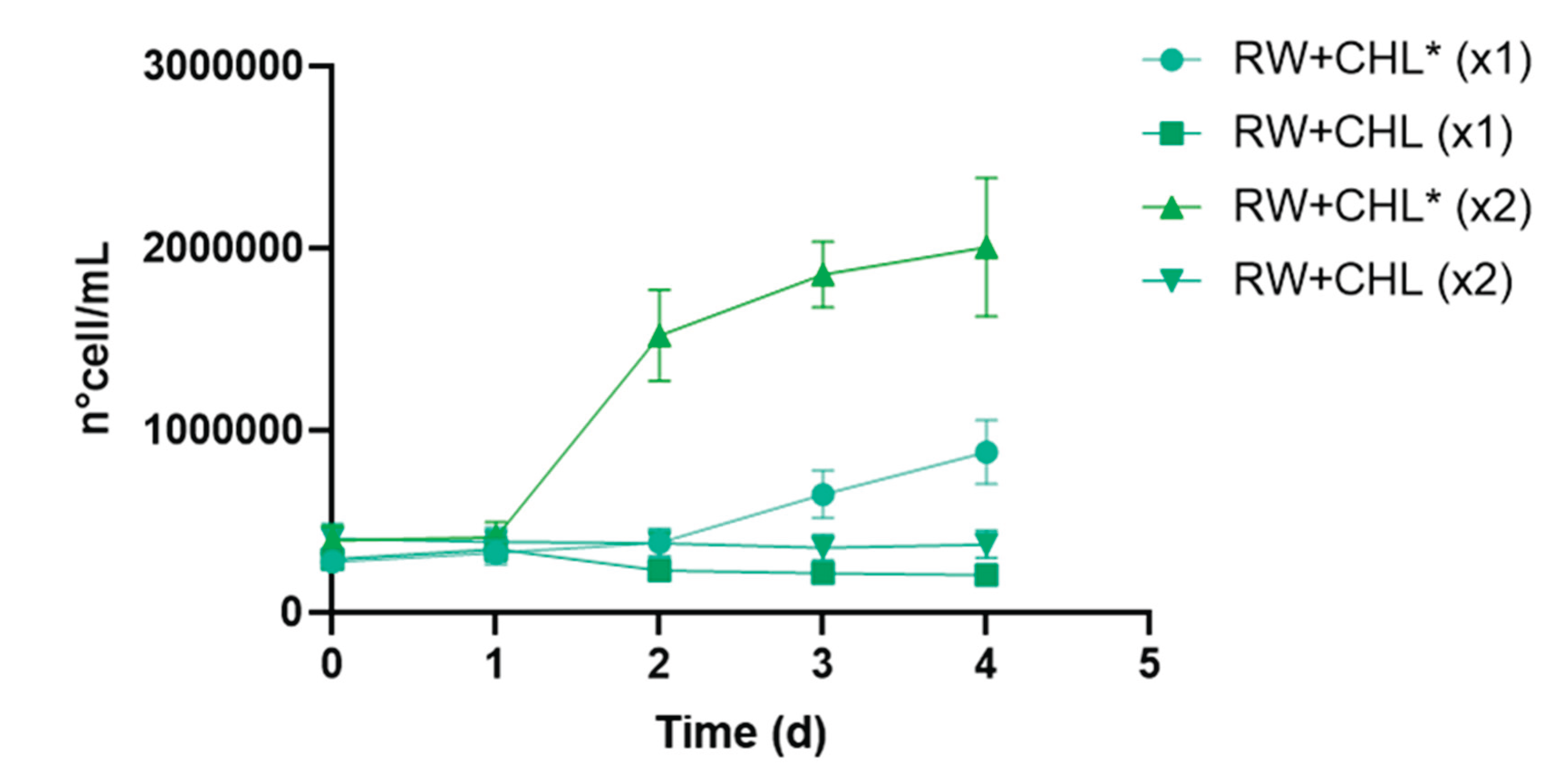

During the microalgae treatment stage, the highest biomass production of

C. vulgaris was achieved under PAR light intensity conditions using an initial inoculum with double the cell density (RW+CHL* X2;

Figure 5). Under these conditions,

C. vulgaris biomass increased fivefold in four days, with a specific growth rate (µ) of 0.752 d⁻¹ and a doubling time (dt) of 0.921 d. At the end of the experiment, total sugar reduction reached 20.5%, along with 92.7% ammonium removal and 79.3% soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP) removal (

Table 2,

Figure 4). In contrast, the treatment with the same inoculum under low light intensity conditions (RW+CHL X2) showed no biomass increase, although it achieved the highest total sugar removal (25.4%), indicating greater utilization of organic compounds as an energy source under light-limited conditions (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Nutrient removal in this treatment did not differ significantly from the high light condition culture, reaching 89.6% ammonium and 61.3% SRP removal (

Table 2). This behavior has been previously reported, indicating that under prolonged environmental conditions with limited light, microalgae can metabolize sugars for survival [

35,

42,

43].

Regarding the treatments with lower cell density inoculum (X1), no biomass growth was observed, and sugar removal efficiency was below 17% for RW+CHL* X1 and 11% for RW+CHL X1. In these treatments, nutrient removal over four days reached 80.1% ammonium and 51.3% SRP for the high light condition, and 72.6% ammonium and 36.5% SRP for the low light condition.

COD reduction was significant in all

C. vulgaris treatments compared to the control culture (

Figure 3). Although the native microbiota in the RW effluent contributed to COD reduction, treatments with

C. vulgaris at higher initial cell density (X2), under both lighting conditions, showed more pronounced decreases (

Table 2). This improvement can be attributed to the ability of the

C. vulgaris LMPA-40 strain to switch between autotrophic and heterotrophic metabolism. This metabolism flexibility allows the microalgae to produce O

2, fix CO

2, and assimilate various sources of organic carbon such as sugars, acetate, glycerol, and organic matter from wastewater [

40,

42,

44,

45,

46].

The integrated bioprocess, which included inoculation with the

C. ethanolica H3 yeast strain, clarification, enrichment with a second RTW stream, and subsequent incorporation of

C. vulgaris LMPA-40 strain at higher initial cell density (X2), resulted in an accumulated COD reduction of 90.6% under high light condition and 90.8% under low light condition, measured from raw RHW effluent to the end of the treatment process (

Figure 3). Similarly, treatments with

C. vulgaris at lower initial inoculum (X1) achieved substantial COD reductions of 77.5% under high light condition and 79.8% under low light condition. In all cases, significant removals of both COD and total sugar were achieved within a 9-day period (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Also, revalorization of RTW as a useful resource has been observed previously demonstrating that it can be an effective nutrient source [

47].

4. Conclusions

The integrated bioprocess, combining a yeast (C. ethanolica) treatment followed by a microalga (C. vulgaris) treatment, proved effective reducing the main contamination parameters of industrial effluent from honey processing facility within a total residence time of 9 days. This approach is based on the synergy between respiratory metabolism and either autotrophic or an alternative heterotrophic process enabling the progressive biotransformation of complex compounds into simpler and available forms.

Notably, the system demonstrated remarkable adaptability to variable environmental conditions, such as fluctuating solar radiation, which is a key factor for its implementation in outdoor treatment systems. The resilience observed under both high and low light conditions highlights the robustness of the proposed approach and its potential for scaling up for real in-situ applications in honey processing facilities.

Moreover, the system enables the integration of domestic effluents (such as greywater and blackwater from the other sectors of the facility), promoting a comprehensive and decentralized solution for managing all liquid waste generated by this economic activity. This feature reinforces its value as a nature-based solution, characterized by low-cost, low energy consumption, adaptability, and alignment with principles of circular economy and environmental sustainability, contributing to the mitigation of both grey water footprint and carbon footprint of the generating company.

Author Contributions

Juan Gabriel Sánchez Novoa: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing, Visualization. Natalia Rodríguez: Data curation, Writing - review and editing. Tomás Debandi: Data curation, Writing - review and editing. Laura I de Cabo: Writing - review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Juana M Navarro Llorens: Writing - review and editing. Patricia L Marconi: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Supervision Writing - review and editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 2020-2681), CONICET (PIP 1122021 0100641) and Fund. Científica Felipe Fiorellino, U. Maimónides, Argentina (to JGSN, PLM). The APC was funded by Fund. Científica Felipe Fiorellino, U. Maimónides, Argentina.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available in the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the “Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (CYTED)” through RED RENUWAL 320rt0005.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- G.y.P. Secretaría de Agricultura, Secretaría de agricultura, ganadería y pesca. https://magyp.gob.ar/apicultura/material_descarga.php (12 9 2023).

- OEC-WORLD, The observatory of economic complexity. https://oec.world/es/profile/hs/honey (20 8 2023).

- Sathya, K.; Nagarajan, K.; Carlin Geor Malar, G.; Rajalakshm, S.; Raja Lakshm, P. A comprehensive review on comparison among effluent treatment methods and modern methods of treatment of industrial wastewater effluent from different sources. Appl. Water Sci. 12, 2022, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra, A.; Chapagain, A.; Aldaya, M.; Mekonnen, M. The water footprint assessment manual setting the global standard, 2011, Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute:Faculty Publications 77. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/wffdocs/77.

- Hossain, M.L.; Lim, L.Y.; Hammer, K.; Hettiarachchi, D.; Locher, C. A review of commonly used methodologies for assessing the antibacterial activity of honey and honey products, Antibiotics 11, 2022, 975. [CrossRef]

- Oryan, A.; Alemzadeh, E.; Moshiri, A. Biological properties and therapeutic activities of honey in wound healing: A narrative review and meta-analysis, J. Tissue Viability 25, 2016, 98-118. [CrossRef]

- Kwakman, P.H.S.; Velde, A.A.T.; de Boer, L.; Speijer, D.; Christina Vandenbroucke-Grauls, M.J.; Zaat, S.A.J. How honey kills bacteria, The FASEB J. 24, 2010, 2576-2582. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Novoa, J.G.; Domínguez, F.G.; Pajot, H.; de Cabo, L.I.; Navarro Llorens, J.M.; Marconi, P.L. Isolation and assessment of highly sucrose-tolerant yeast strains for honey processing factory’s effluent treatment, AMB Express. 14, 2024, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Halder, G.N.; Gunapati, O.; Indrama, T.; Tiwari, O.N. Chapter 17 - Bioremediation of organic and inorganic pollutants using microalgae, New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2019, pp. 223-235. [CrossRef]

- de Cabo Laura, L.; Marconi, P. L. Eds. Estrategias de remediación para las cuencas de dos ríos urbanos de llanura: Matanza-Riachuelo y Reconquista, 2021, Ed. Fundación Azara. ISBN 978-987-3781-74-2. https://fundacionazara.org.ar/estrategias-de-remediacion-para-las-cuencas-de-dos-rios-urbanos-de-llanura-matanza-riachuelo-y-reconquista/.

- Rajamanickam, R.; Selvasembian, R. Insights into the potential of Chlorella species in the treatment of hazardous pollutants from industrial effluent. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. A41, 2025, 135. [CrossRef]

- Groppa, M.D.; Trentini, A.; Zawoznik, M.; Bigi, R.; Nadra, C.; Marconi, P. Assessment and optimization of a bioremediation strategy for an urban stream of Matanza-Riachuelo Basin, Int. J. Environ. Eng. 13, 2019, 418-424. https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/159748 (12 9 2023).

- Marconi, P.L.; Trentini, A.; Zawoznik, M.; Nadra, C.; Mercadé, J.M.; Sánchez Novoa, J.G.; Orozco, D.; Groppa, M.D. Development and testing of a 3D-printable polylactic acid device to optimize a water bioremediation process, AMB Express. 10, 2020, 142. [CrossRef]

- González-López, F.; Rendón-Castrillón, L.; Ramírez-Carmona, M.; Ocampo-López, C. Evaluation of a Landfill Leachate Bioremediation System Using Spirulina sp. Sustainability, 17, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Najar-Almanzor, C.E.; Velasco-Iglesias, K.D.; Solis-Bañuelos, M.; González-Díaz, R.L.; Guerrero-Higareda, S.; Fuentes-Carrasco, O.J.; García-Cayuela, T.; Carrillo-Nieves, D. Chlorella vulgaris-mediated bioremediation of food and beverage wastewater from industries in Mexico: Results and perspectives towards sustainability and circular economy, Sci. Total Environ. 940, 2024, 173753. [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Nayak, M.; Ghosh, A. A review on co-culturing of microalgae: A greener strategy towards sustainable biofuels production, Sci. Total Environ. 802, 2022, 149765. [CrossRef]

- Sobolewska, E.; Borowski, S.; Kręgiel, D. Cultivation of yeasts on liquid digestate to remove organic pollutants and nutrients and for potential application as co-culture with microalgae, J. Environ. Manage. 362, 2024, 121351. [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Patel, A.; Mehtani, J.; Pruthi, P.A.; Pruthi, V.; Poluri, K.M. Co-culturing of oleaginous microalgae and yeast: paradigm shift towards enhanced lipid productivity, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 26, 2019, 16952-16973. [CrossRef]

- Ashtiani, V.; Jalili, H.; Rahaie, M.; Sedighi, M.; Amrane, A. Effect of mixed culture of yeast and microalgae on acetyl-CoA carboxylase and Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase expression, J. Biosci. Bioeng. 131, 2021, 364-372. [CrossRef]

- Suastes-Rivas, J.K.; Hernández-Altamirano, R.; Mena-Cervantes, V.Y.; Valdez-Ojeda, R.; Toledano-Thompson, T.; Tovar-Gálvez, L.R.; López-Adrián, S.; Chairez, I. Efficient production of fatty acid methyl esters by a wastewater-isolated microalgae-yeast co-culture, Environ Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27, 2020, 28490-28499. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Karitani, Y.; Yamada, R.; Matsumoto, T.; Ogino, H. Co-utilization of microalgae and heterotrophic microorganisms improves wastewater treatment efficiency, App. Microbiol. Biotechnol.108, 2024, 468. [CrossRef]

- Hyungseok, Y.; Kyu-Hong, A.; Hyung-Jib, L.; Kwang-Hwan, L.; Youn-Jung, K.; Kyung-Guen, S. Nitrogen removal from synthetic wastewater by simultaneous nitrification and denitrification (SND) via nitrite in an intermittently-aerated reactor, Water Res. 33, 1999, 145-154. [CrossRef]

- Marconi, P.L. Alvarez, M.A.; Klykov S.P.; Kurakov, V.V. Application of a mathematical model for production of recombinant antibody 14D9 by Nicotiana tabacum cell suspension batch culture, BioProcess Int. 12, 2014, 42-49.

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. A colorimetric method for the determination of sugars, Nature. 168, 1951, 167-167. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances, Anal. Chem. 28 1956 350-356. [CrossRef]

- APHA, Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 23 ed., American Public Health Association, Washington DC, 2017.

- Di Rienzo, J.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M. G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.: Robledo, C.W. InfoStat versión Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina, retrieved from. http://www.infostat.com.ar 2013.

- Tukey, J. Some selected quick and easy methods of statistical analysis, Trans. NY Acad. Sci. 16, 1953, 88-97. [CrossRef]

- Escuredo, O.; Dobre, I.; Fernández-González, M.; Seijo, M.C. Contribution of botanical origin and sugar composition of honeys on the crystallization phenomenon, Food Chem. 149, 2014, 84-90. [CrossRef]

- Tafere, D.A. Chemical composition and uses of Honey: A Review, J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 4, 2021, 194-201. [CrossRef]

- Young, G.W.Z.; Blundell, R. A review on the phytochemical composition and health applications of honey, Heliyon 9, 2023, e12507. [CrossRef]

- C.A.S.f. Honey, Codex Alimentarius Commission. Standard for Honey CXS, 2019.

- Fattori, S.B. “LA MIEL” Propiedades, composición y análisis físico- químico. s.l.: www.apimondia.org, 2004.

- D’Amore, T.; Russell, I.; Stewart, G.G. Sugar utilization by yeast during fermentation, J. Ind. Microbiol. 4, 1989, 315-323. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.A.; Höffner, K.; Barton, P.I. From sugars to biodiesel using microalgae and yeast, Green Chem. 18, 2016, 461-475. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.; Gordon, R. Beyond micromachining: the potential of diatoms. Trends in Biotechnol. 17(5), 1999, 190-196. [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen-Jensen, M. Proposal for the treatment of effluents from the production of craft beer, Degree thesis in civil engineering, UNCPBA, Buenos Aires, 2020.

- Leung, S.M.; Little, J.C.; Holst, T.; Love, N. G.; Air/water oxygen transfer in a biological aerated filter, J. Environ. Engineering 132, 2006, 181-189. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zurano, A.; Lafarga, T.; Morales-Amaral, M.D.M.; Gómez-Serrano, C.; Fernández-Sevilla, J.M.; Acién-Fernández, F.G.; Molina-Grima, E. Wastewater treatment using Scenedesmus almeriensis: effect of operational conditions on the composition of the microalgae-bacteria consortia, J. Appl. Phycol. 33, 2021, 3885-3897. [CrossRef]

- Trentini, A.; Groppa, M.; Zawoznik, M.; Bigi, R.; Perelman, P.; Marconi, P. Biorremediación del lago Lugano de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires por algas unicelulares—estudios preliminares para su posterior utilización, Terra Mundus 4 ,2017.

- Van Do, T.C.; Nguyen, T.N.T.; Tran, D.T.; Le, T.G.; Nguyen, V.T. Semi-continuous removal of nutrients and biomass production from domestic wastewater in raceway reactors using Chlorella variabilis TH03-bacteria consortia, Environ. Technol. Innov. 20, 2020, 101172. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sánchez, D.; Martinez-Rodriguez, O.A.; Kyndt, J.; Martinez, A. Heterotrophic growth of microalgae: metabolic aspects, World J. Microb. Biot. 31, 2015, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Michelon, W.; Pirolli, M.; Mezzari, M.P.; Soares, H.M.; da Silva, M.L.B. Residual sugar from microalgae biomass harvested from phycoremediation of swine wastewater digestate, Water science and technology: a journal of the International Association on Water Pollution Research 79, 2019, 2203-2210. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, K.K.; Kumar, S.; Dixit, D.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, D. ; Jawed, A.; Haque, S. Implication of industrial waste for biomass and lipid production in Chlorella minutissima under autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic grown conditions, Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 176, 2015, 1581-1595. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sánchez, D.; Martinez-Rodriguez, O.A.; Martinez, A. Heterotrophic cultivation of microalgae: production of metabolites of commercial interest, J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 92, 2017, 925-936. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, O.; Escalante, F.M.E.; de-Bashan, L.E.; Bashan, Y. Heterotrophic cultures of microalgae: Metabolism and potential products, Water Research. 45, 2011, 11-36. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Cho, K. H.; Ligaray, M.; Choi, M. J. Organic matter composition of manure and its potential impact on plant growth, Sustainability, 11, 2019, 1-12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).