1. Introduction

Complicated components with numerous small key local features (KLFs) are commonly used in modern advanced manufacturing industries such as aerospace, marine engineering, and automotive sectors. Automated and accurate 3D shape measurement of these features is critical for ensuring quality control, enhancing product reliability, and minimizing manufacturing costs [

1,

2,

3]. Three-dimensional (3D) shape measurement techniques are generally classified into contact and non-contact approaches. Among contact-based methods, coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) equipped with tactile probes [

4] offer exceptional precision. Nevertheless, they are constrained by low efficiency in acquiring high-density 3D point cloud data. In recent years, structured light sensors [

5,

6,

7], known for their non-contact nature, high precision, and efficiency, have been widely used in industrial applications and integrated with CMMs for 3D shape measurements. However, the combined method, which integrates CMMs with a structured light sensor [

8], is not suitable for online measurements due to its restrictive mechanical structure and limited measurement efficiency. In contrast to CMMs, industrial robots are well-suited for executing complex spatial positioning and orientation tasks with efficiency. Equipped with a high-performance controller, these robots can also transport a vision sensor mounted on the end-effector to specified target locations. During the online measurement process, the spatial pose of the vision sensor varies as the robot’s end-effector moves to different positions. Nevertheless, the relative transformation between the sensor’s coordinate system and the end-effector remains fixed—an essential concept known as hand–eye calibration. Consequently, the accuracy of this calibration plays a pivotal role in determining the overall measurement accuracy of the system.

For hand–eye calibration, techniques are generally classified into three categories based on the nature of the calibration object: 2D target-based methods, single-point or standard-sphere-based methods, and 3D-object-based methods. One of the most widely recognized hand–eye calibration methods based on a two-dimensional calibration target was introduced by Shiu [

9]. The fundamental constraint of the calibration process is derived by commanding the robot to move the vision sensor and observe the calibration target from multiple poses. Consequently, the hand–eye calibration problem is formulated as solving the homogeneous matrix equation AX=XB. Since then, a wide range of solution methods have been developed for these calibration equations, which are generally categorized into linear and nonlinear algorithms [

10,

11]. Representative approaches include the distributed closed-loop method, the global closed-loop method, and various iterative techniques. However, these methods tend to be highly sensitive to measurement noise. Compared to typical calibration methods, Sun et al. [

12] introduced a flexible hand–eye calibration method for robotic systems. This approach estimates the hand–eye relationship using only the robot’s predefined motion and a 2D chessboard pattern. In contrast, Xu et al. [

13] proposed a single-point-based calibration method that utilizes a single point—such as a standard sphere—to compute the transformation, offering a relatively simple and practical implementation. Furthermore, hand–eye calibration methods utilizing a standard sphere of known radius have been extensively adopted to estimate the hand–eye transformation parameters [

14]. These methods provide an intuitive and user-friendly solution for determining both rotation and translation matrices. Among the 3D-object-based calibration methods, Liu et al. [

15] designed a calibration target consisting of a small square with a circular hole. Feature points were extracted from line fringe images and used as reference points for the calibration process. However, the limited number of calibration points and the low precision of the extracted image features resulted in suboptimal calibration accuracy. In addition to hand-eye calibration methods based on calibration objects, several approaches that use environmental images, rather than calibration objects, have been successfully applied to determine hand-eye transformation parameters, as reported by Sang [

16] and Nicolas and Qi [

17]. Song et al. [

18] proposed a robot hand–eye calibration algorithm based on irregular targets, where the calibration is achieved by registering multi-view point clouds using FPFH-based sampling consistency and a probabilistic ICP algorithm, followed by solving the derived spatial transformation equations. However, the methods mentioned above do not account for the robot positioning errors introduced by kinematic parameter errors during the hand-eye calibration process.

To overcome this limitation, many researchers have proposed various hand-eye calibration methods that account for the correction of robot kinematic parameter errors. Yin et al. [

19] introduced an enhanced hand-eye calibration algorithm. Initially, hand-eye calibration is conducted using a standard sphere, without accounting for robot positioning errors. Then, both the robot’s kinematic parameters and the hand-eye relationship parameters are iteratively refined based on differential motion theory. Finally, a unified identification of hand-eye and kinematic parameter errors is accomplished using the singular value decomposition (SVD) method. However, the spherical constraint-based error model lacks absolute dimensional information, and cumulative sensor measurement errors further limit the accuracy of parameter estimation. Li et al. [

20] introduced a method that incorporates fixed-point information as optimization constraints to concurrently estimate both hand-eye transformation and robot kinematic parameters. However, the presence of measurement errors from visual sensors substantially compromises the robustness and generalizability of the resulting parameter estimations. To further optimize measurement system parameters, Mu et al. [

21] introduced a unified calibration method that simultaneously estimates hand-eye and robot kinematic parameters based on distance constraints. However, this method does not adequately address sensor measurement error correction during the solution of the hand-eye matrix, resulting in accumulated sensor inaccuracies that significantly degrade the precision of the derived relationship matrix.

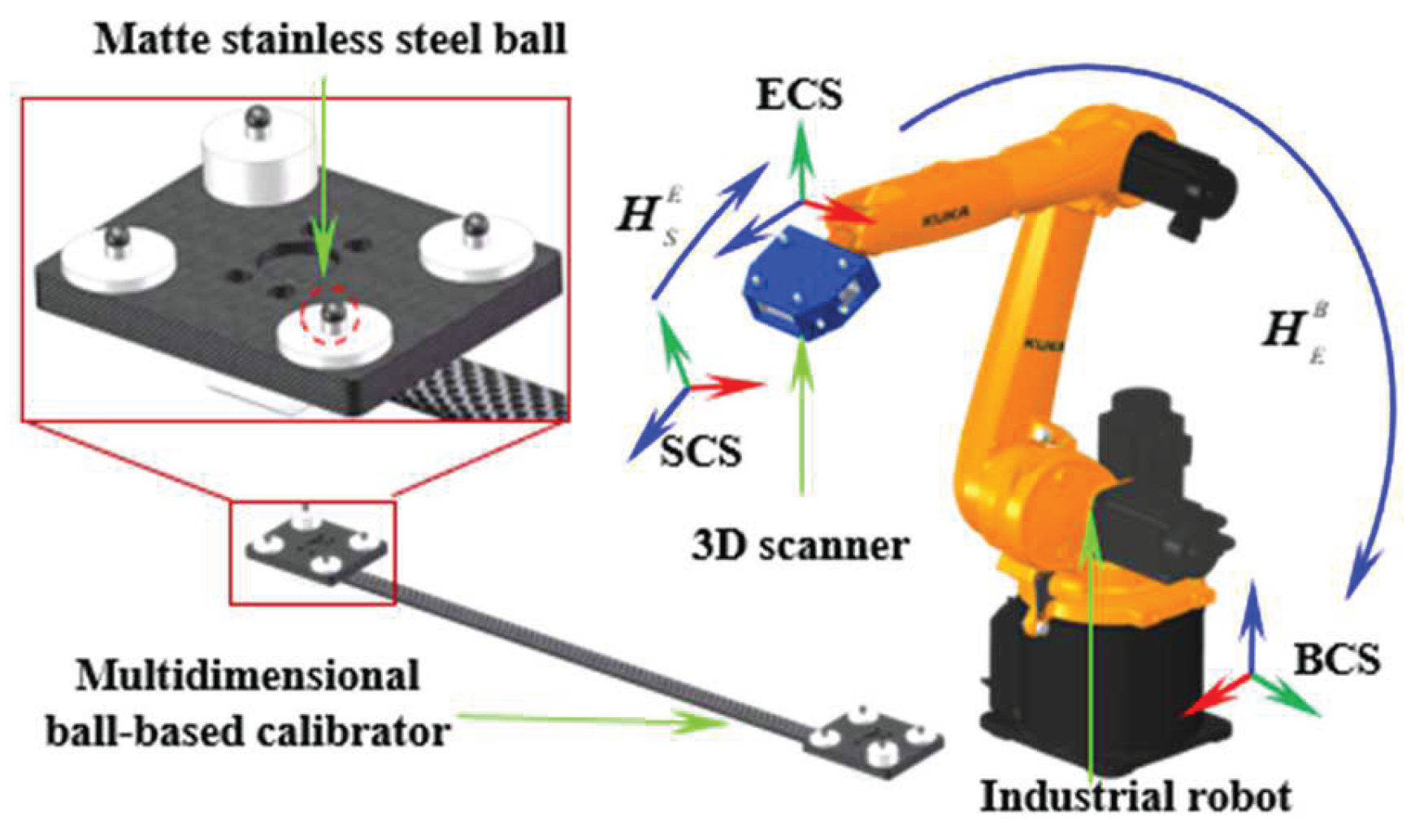

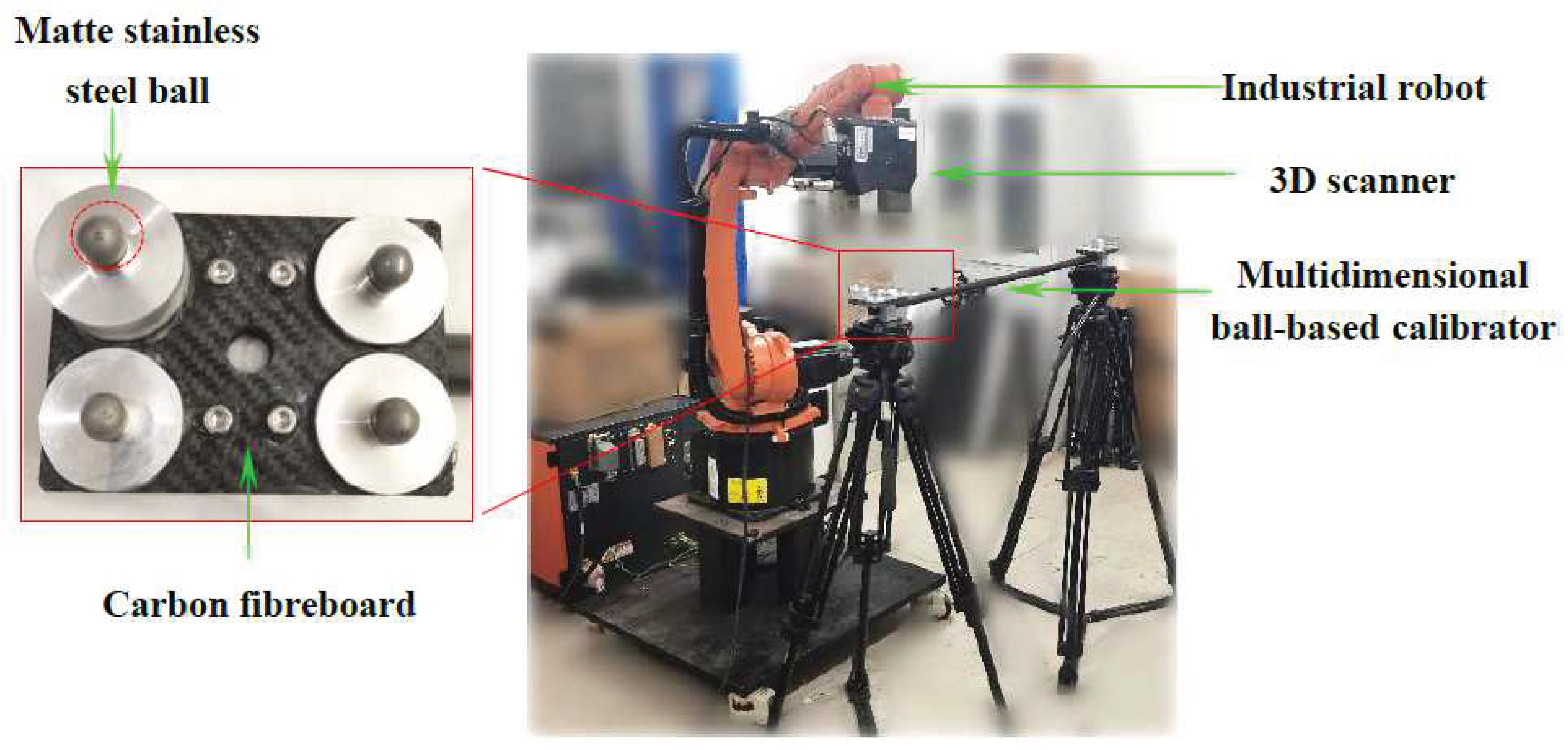

To address the aforementioned limitations, we propose an accurate calibration method for a robotic flexible 3D scanning system based on a multidimensional ball-based calibrator (MBC) [

22]. This method constructs a distance-based calibration model that concurrently considers measurement errors, hand-eye parameter errors, and robotic kinematic errors. Specifically, by incorporating angular-constraint-based optimization for compensating coordinate errors of the measurement points, a preliminary hand-eye calibration method is introduced based on a single virtual point determined via the barycenter technique. Subsequently, a distance-constraint-based calibration method is developed to further optimize both hand-eye and kinematic parameters, effectively associating system parameter errors with deviations in the measured coordinates of the single virtual point.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the model of the measurement system.

Section 3 outlines the proposed calibration methodology.

Section 4 presents the experimental setup and accuracy validation. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the study with a brief summary of the findings.

3. Measurement System Calibration

To improve the accuracy of hand-eye calibration, the paper proposed an online accurate calibration method using a multidimensional ball-based calibrator (MBC) to simultaneously identify both hand-eye transformation and robot kinematic parameters. A schematic of the calibration procedure is presented in

Figure 2. First,

Section 3.1 introduces an initial hand-eye calibration method that compensates for measurement point errors using an angular-constraint-based optimization method. This method is based on a virtual point calculated via the barycenter algorithm. Subsequently,

Section 3.2 presents a distance-constraint-based calibration strategy to further refine the estimation of both hand-eye transformation and kinematic parameters.

3.1. Initial Calibration of the Hand-Eye Parameters

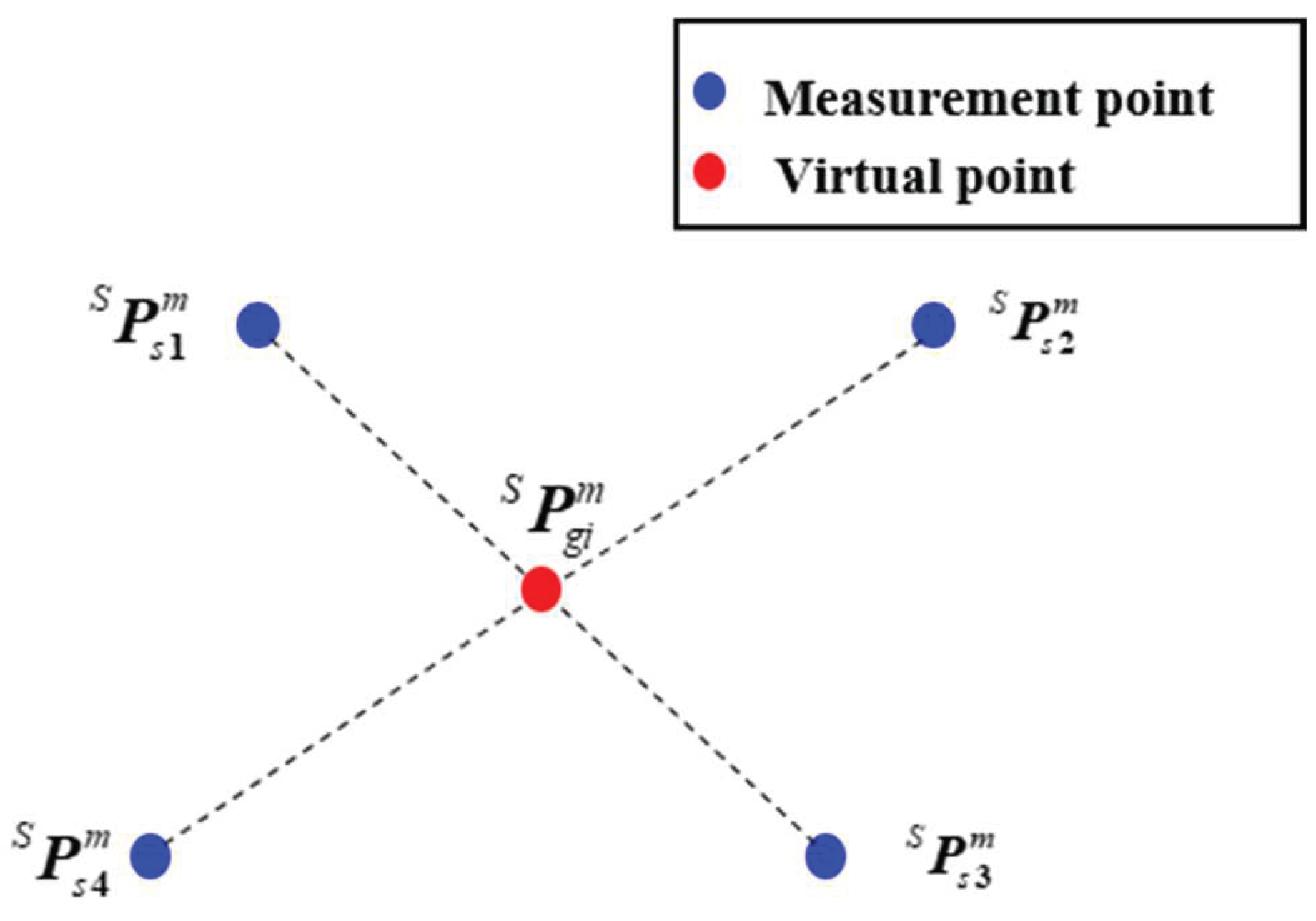

3.1.1. Preliminary Hand-Eye Calibration Method based on a Virtual Single Point

During the initial stage of hand-eye calibration, the MBC is stably positioned within a suitable workspace. A single virtual point, serving as the calibration target, is calculated based on the coordinates of four measurement points optimized using an angular-constraint-based optimization method. Specifically, the initial hand-eye transformation is then determined by capturing this virtual point from multiple robot’s poses using the 3D scanner. Furthermore, the position of the single virtual point relative to the BCS remains constant. According to the principle of barycentric coordinates, an initial (non-optimized) virtual point

, as illustrated in

Figure 2, is computed based on the initial coordinates of four measurement points

, and is formulated as follows:

When the 3D scanner moves to the

i-th and

j-th poses, the following equations considering the measurement deviation can be obtained according to Equation (1):

where

, computed by the optimized method introduced in section 3.1.2, is the deviation between the nominal and actual coordinates of the single virtual point in the SCS.

By translating the 3D scanner multiple times to measure the points, a matrix equation with form of

is given by:

The unknown matrixis determined using the singular value decomposition (SVD) algorithm. Subsequently, the unknown translation vectoris calculated via the least squares method. Since measurement errors at the target point substantially affect the overall calibration accuracy, it is essential to optimize the coordinates of the measurement points acquired by the 3D scanner.

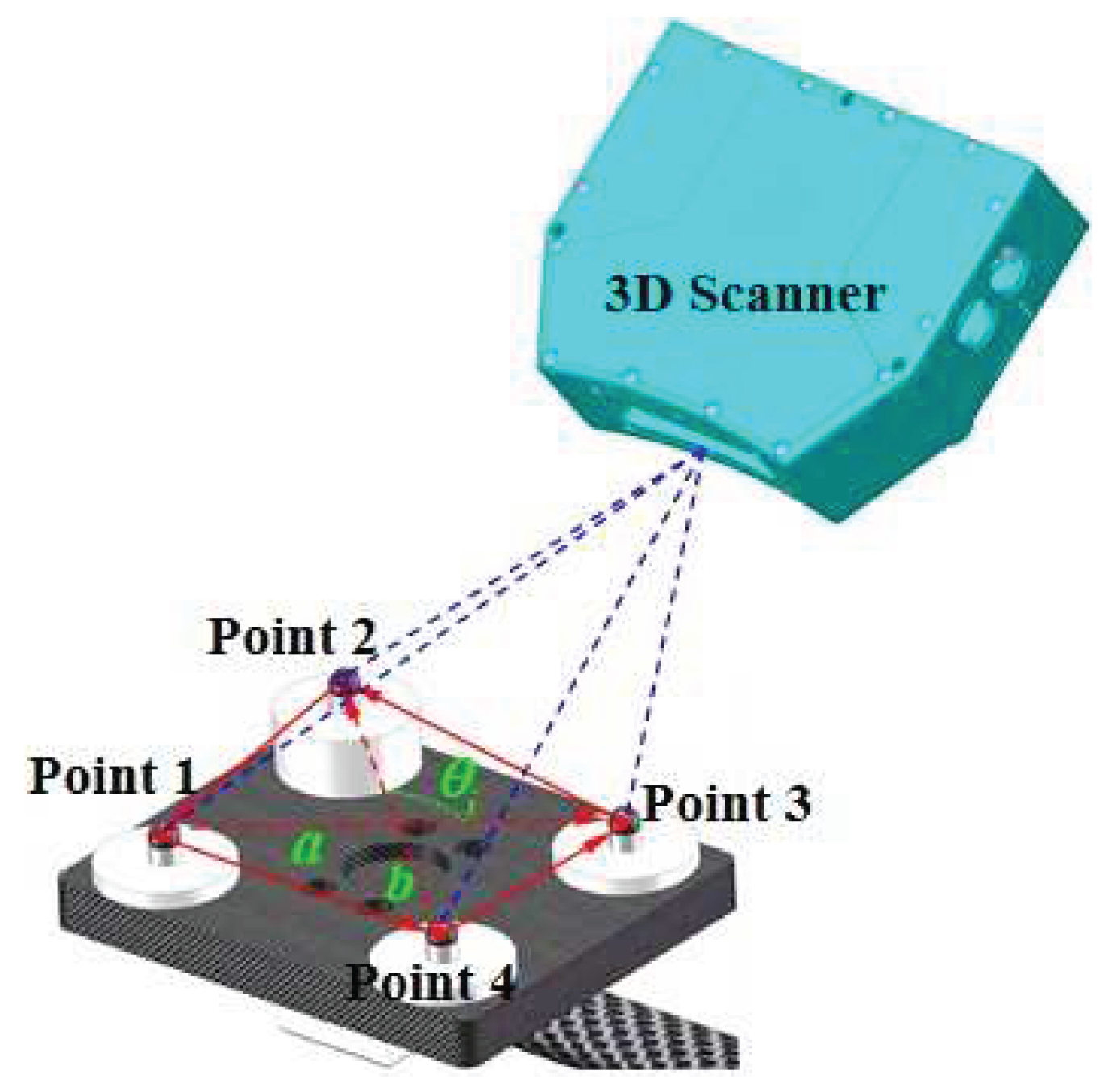

3.1.2. Measurement Error Identification Method

To identify and compensate for the measurement errors of the measurement points, an adjustment optimization method based on the angle constraints is introduced, and the diagram of a spatial angle constructed by two nonzero vectors is shown in

Figure 3.

Based on the property that the angle between two vectors in Euclidean space is independent of the coordinate system, the angle values formed by the target points on the MBC are considered as the reference true values. These points are pre-calibrated using a high-precision CMM. The angular values derived from the measured coordinates on the MBC are then compared with the reference true to establish an angular error equation.

According to the angle information composed of the initial measurement points in the MBC, the arccosine function is given by:

where

is the angle between the vectors

a and

b.

Next, the prior angle values are selected as the reference true values. The angular values derived from the field measurements of each target point are then subtracted from the reference true values to form the angular error equation. Taking angle

as an example, we apply a Taylor expansion to Equation (8), neglecting second-order and higher-order terms, resulting in the linearized equation for the angular constraint:

where

represent the coordinate corrections of the initial measurement points, the nominal angle

is calibrated by CMM, and

is the measured angle.

The angular error is characterized by the following mathematical expression, which quantifies the relationship between measurement variables and angular deviation:

To further facilitate analysis, the above equation is reformulated into a matrix form as follows:

where

denotes the vector of coordinate corrections;

represents the angular error vector;

is the coefficient matrix.

According to the principle of least squares adjustment, the normal equations are derived as follows:

where

is weight matrix.

In the paper, the ridge estimation method [

23] was employed to calculate the optimal parameters. As a result, after compensating for measurement errors, an optimized single virtual point

is derived from the adjusted measurement points.

3.2. Accurate Calibration of Robot Kinematic and Hand-Eye Parameters

Discrepancies between the theoretical and actual kinematic parameters of the robot lead to deviations in the end-effector’s pose. Additionally, the robot motion involved in the initial hand-eye calibration process introduces inevitable positioning errors, further compromising calibration accuracy. Measurement errors from the 3D scanner also impose constraints on improving calibration precision. To address these issues, this section presents a joint calibration method based on a stereo target, aiming to simultaneously compensate for both hand-eye and kinematic parameter errors. Specifically, a distance error model is derived for associating the parameter errors with the deviations in the measured coordinates of the single virtual point. By reducing the impact of scanner measurement noise and kinematic deviations, the proposed approach significantly enhances the online calibration accuracy of the integrated robot-scanner system.

Assume that

represents the homogeneous coordinates of a measurement point in the SCS, and the corresponding measurement result in the BCS can be denoted as:

where

and

represent the theoretical values of the robot end-effector pose matrix and the hand-eye transformation matrix, respectively.

Considering the influences of hand-eye calibration errors, robotic kinematic parameter deviations, and scanner measurement errors, the actual position of the measurement point in the BCS can be expressed as:

where

represents the scanner measurement error,

denotes the robotic end-effector pose error, and

corresponds to the hand-eye calibration error.

By subtracting Equation (14) from Equation (13) and neglecting higher-order terms beyond the second order, the deviation between the actual and measured values of the point in the BCS is obtained:

where

is the corrected coordinates of the scanned measurement point. The first term on the right-hand side can be expressed as:

According to differential kinematics, the hand-eye relationship error can be expressed as:

where

is the differential operator.

Thus, the second term on the right-hand side of Equation (15) can be simplified as:

Similarly, the error model for the robot end-effector pose can be expressed as:

where

represents the coordinates of the corrected scan measurement point transformed into the robot base coordinate system, and

represents the robot end-effector pose error model from Equation (4).

By neglecting second-order high-order terms, the hand-eye relationship model incorporating scanner measurement errors and robot kinematic parameter errors is obtained as follows:

where

is the coefficient matrix corresponding to the

i-

tℎ calibration pose of the robot, while

is a vector comprising system parameter errors, including hand-eye parameter errors and robot kinematic parameter errors.

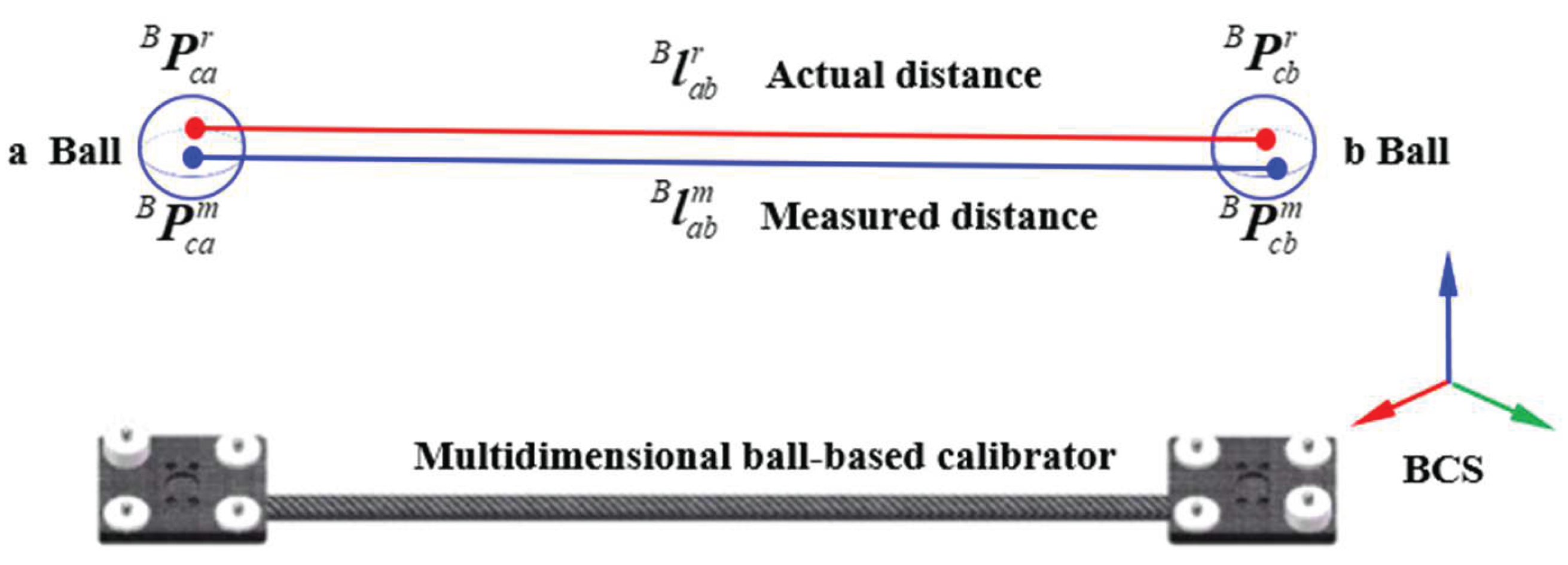

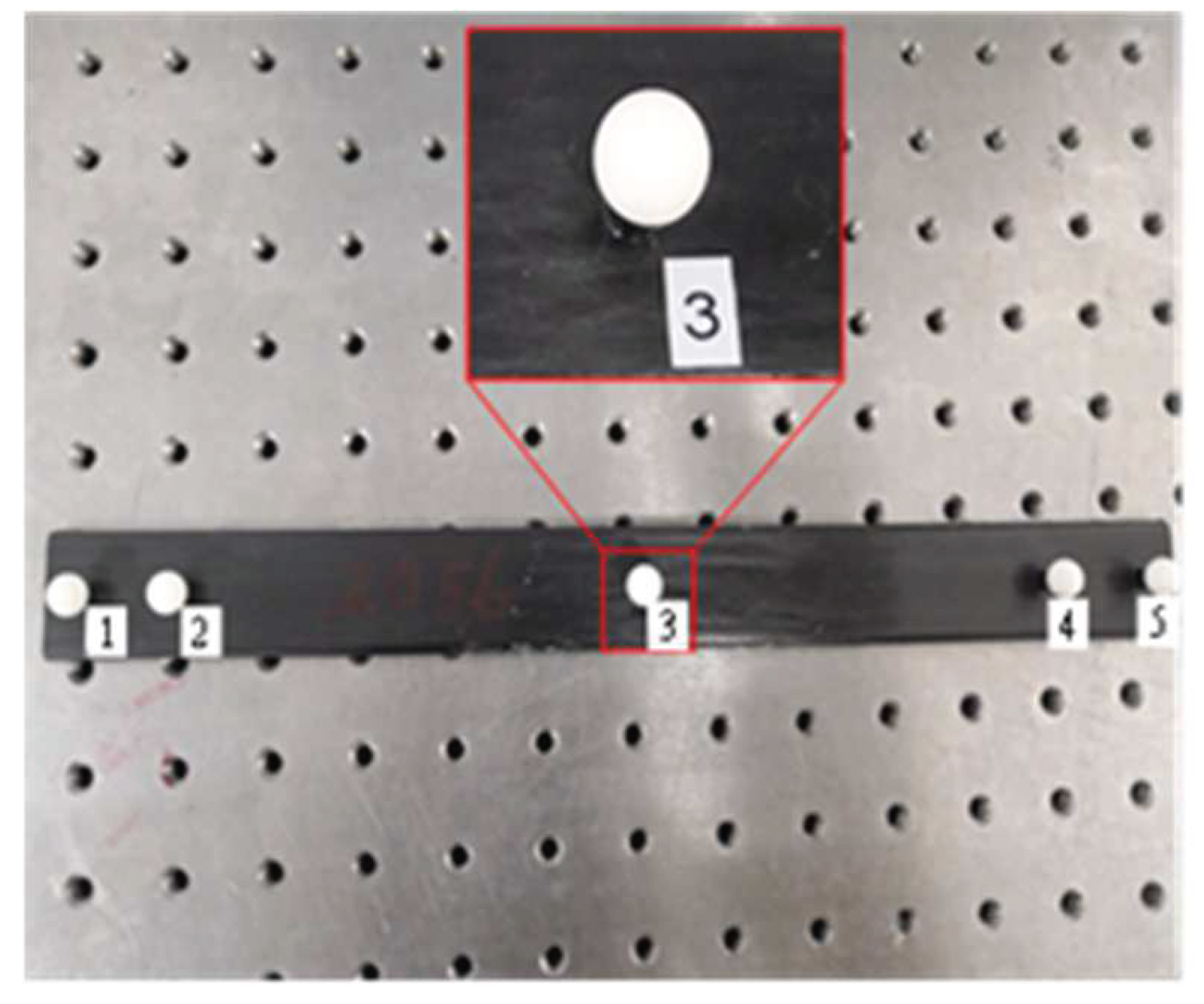

Building upon the preceding research, a system parameter identification model is further developed based on distance error analysis. In Euclidean space, the theoretical distance between two measured points should remain invariant across different coordinate systems. However, discrepancies arise between the theoretical and measured distances of two points in the BCS due to scanner measurement errors, inaccuracies in hand-eye parameters, and deviations in robot kinematic parameters—collectively referred to as distance errors. In the paper, the distance error is defined as the difference between the calibrated distance and the measured distance between the center points of two spheres on the stereo target, as illustrated in the

Figure 4.

Let

and

represent the actual coordinates of points

a and

b on the stereo target in the BCS. Let

and

represent the measured coordinates of the corresponding points. Similarly, let

be the actual distance vector between the two points, and

be the measured distance vector. The error vectors between the measured and actual values of the two points are denoted as

and

, respectively. Then, we have:

Thus, the distance errorbetween the two points can be expressed as:

whereis the distance error vector.

Substituting Equation (20) into the above expression yields:

To refine the kinematic model and hand-eye transformation matrix for improved end-effector scanning accuracy, the position of the stereo target was varied, and the above process was repeated multiple times to establish a system of linear equations. The Levenberg-Marquardt (L-M) algorithm was then employed to solve for system parameter errors, resulting in a more accurate representation of the system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z.; methodology, Z.Z. and X.S; software, J.S.; validation, Z.Z., Y.L. and X.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Z. and D.Z; investigation, Z.Z. and H.L.; resources, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.S.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, X.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.