Submitted:

18 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Limited Model Generalization: Most prior studies have concentrated on optimizing performance within controlled experimental settings, with limited attention to cross-domain generalization or cross-user robustness. This restricts the applicability of current models in complex and dynamic real-world environments.

- Absence of Physiological Constraint Modeling: Existing methods typically lack explicit incorporation of human anatomical structures or kinematic constraints, which often leads to estimations that violate basic biomechanical principles. As a result, the predicted skeletal poses can deviate substantially from physically plausible human motion patterns.

2. Related Work

2.1. Point-Cloud Based

2.2. FFT-Spectrum Based

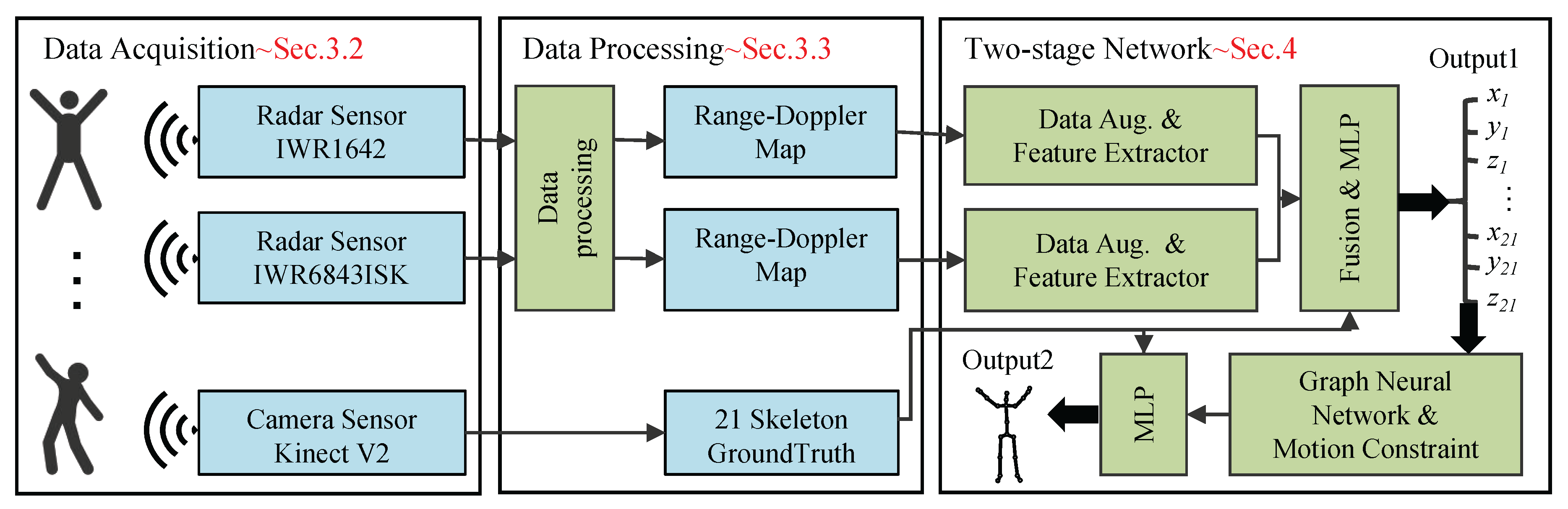

3. Radar Data Acquisition and Processing

3.1. Operating Principle of FMCW Radar

3.2. Experimental Setup and Data Acquisition

3.2.1. Data Acquisition Platforms

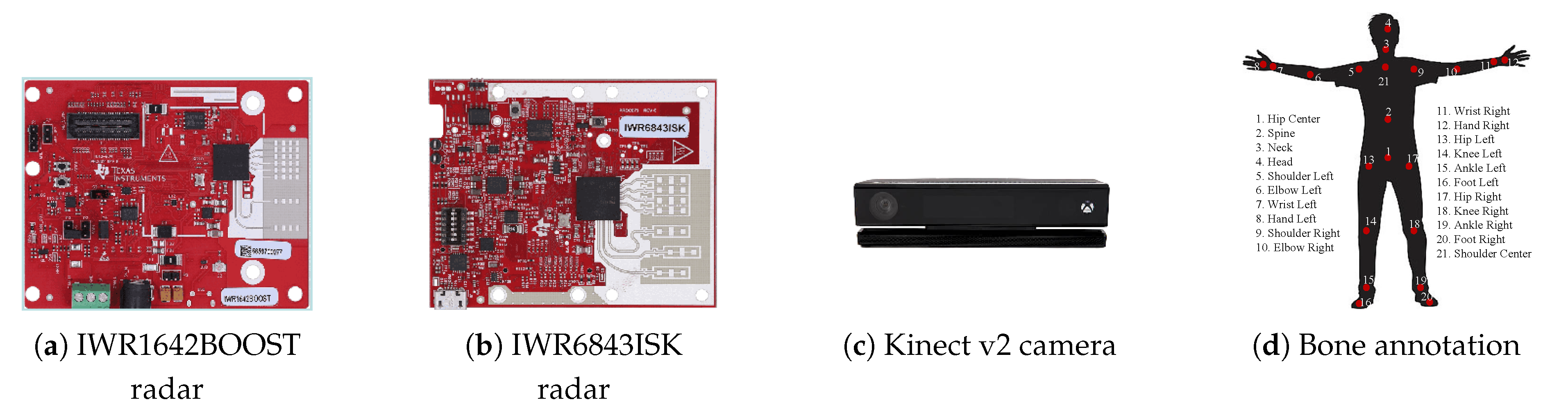

- mmWave FMCW Radar Sensing: As illustrated in Figure 2(a) and (b), the system integrates two commercial mmWave FMCW radars from Texas Instruments—the IWR1642BOOST and IWR6843ISK—as primary sensing devices. These radars are connected to the DCA1000EVM data capture module, enabling efficient acquisition and real-time transmission of raw radar signals.

- Optical Groundtruth Annotation: As shown in Figure 2(c), the system employs the Microsoft Kinect V2 optical sensor as the groundtruth annotation device. This sensor provides high-precision three-dimensional coordinates for 21 skeletal joints, as depicted in Figure 2(d), as a reliable reference for subsequent algorithm training.

- Synchronization and Control System: Two high-performance computers functioning as the control center manage the entire system. Time synchronization across multiple data sources is achieved using the Network Time Protocol (NTP), enabling millisecond-level timestamp alignment and ensuring temporal consistency among different modalities.

- Radar Configuration: The core parameters of the two radars are optimized as shown in Table 1. The IWR1642BOOST operates in the 77 GHz mmWave band, employing a 2-transmitter, 4-receiver antenna array design, which forms 8 equivalent channels in the azimuth dimension through MIMO virtual aperture technology. The IWR6843ISK operates at 60 GHz, featuring a 3-transmitter, 4-receiver antenna array to enhance elevation resolution. Notably, other parameters remain consistent across both devices: the effective bandwidth is set to 3.072 GHz, the number of samples per frame is fixed at 256, and the frame period is strictly controlled at 50 ms.

3.2.2. Data Acquisition and Action Design

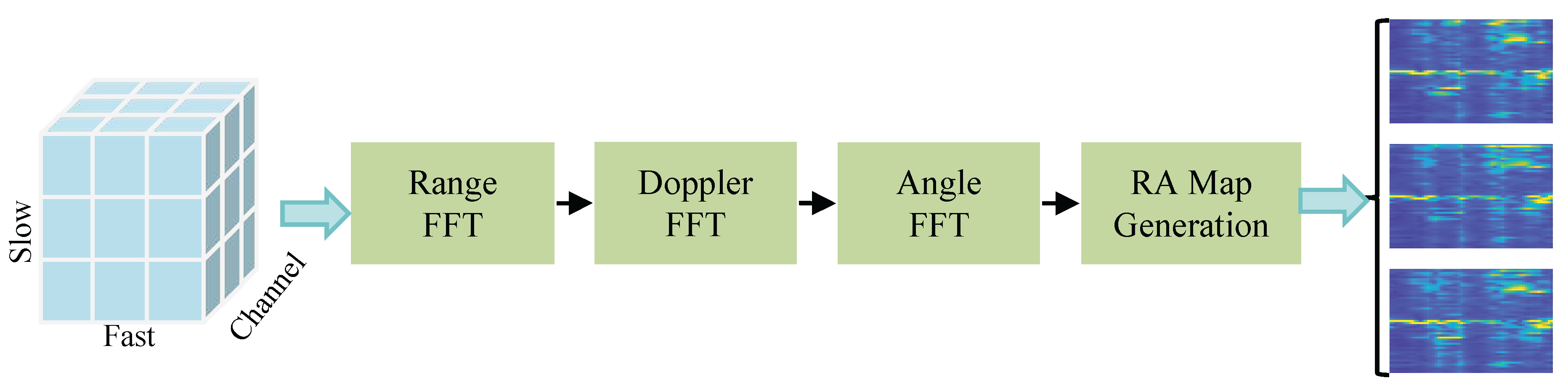

3.3. Signal Processing Pipeline for RA Map Generation

- Range Processing: Perform a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) along the fast-time axis (i.e., within each chirp) to obtain the range profilewhere denotes the IF signal for the i-th chirp, m-th antenna element, n-th sample within a chirp; and k indexes the range bins.

- Doppler Processing: Apply an FFT along the slow-time axis (i.e., across chirps) to generate the Range-Doppler mapwhere is the number of chirps per frame, and p indexes the Doppler bins.

- Angle Processing: Perform an FFT across the multiple receiver antennas to resolve the angular position of targetswhere is the number of receiver antennas, and q indexes the angle bins.

- RA Heatmap Generation: Generate the RA heatmap by extracting the zero-Doppler slice or integrating over the Doppler dimension of the radar data cube

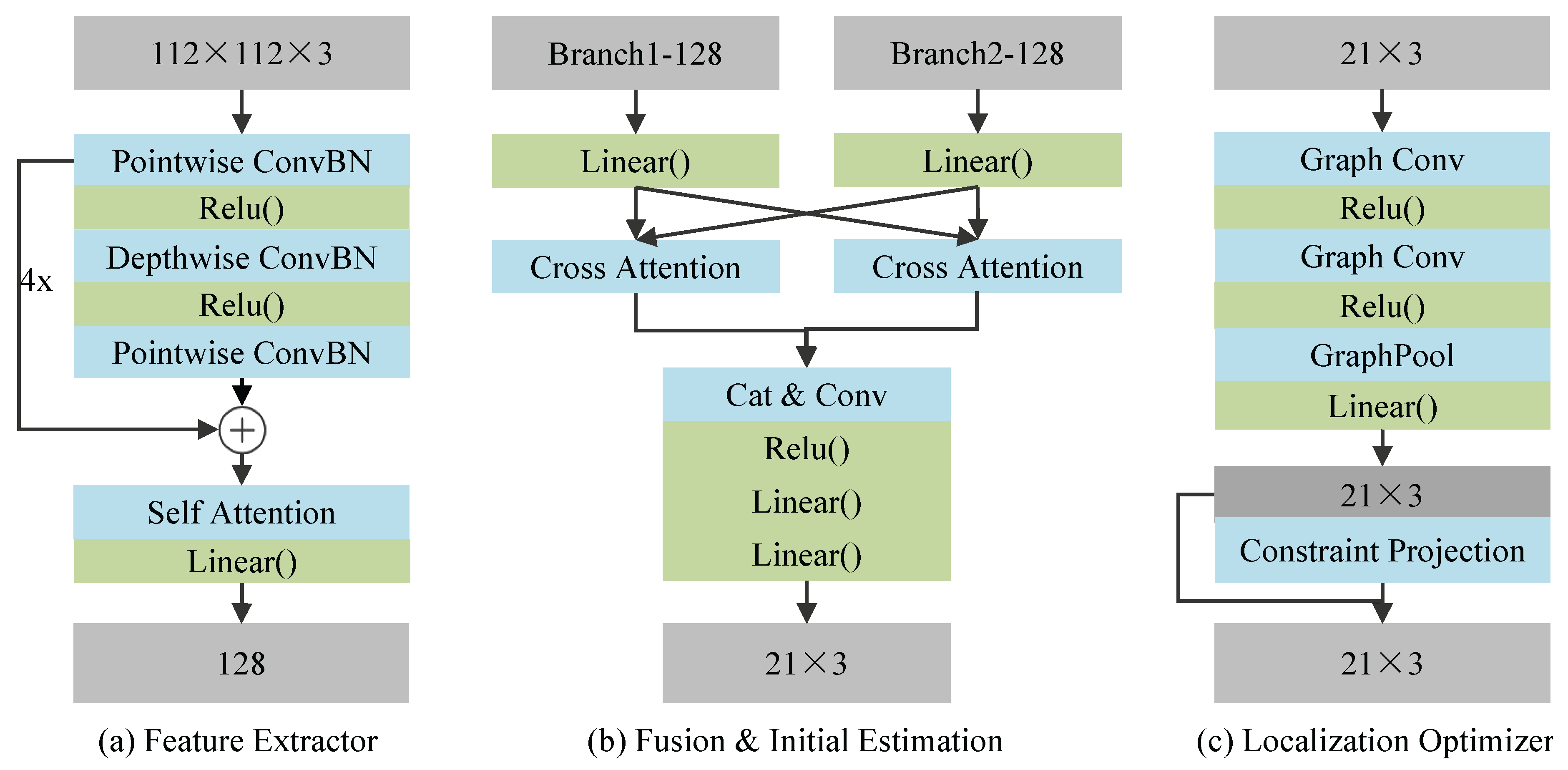

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Augmentation

- Temporal Augmentation: Each radar heatmap sequence comprises T consecutive frames, with each sample consisting of 5 frames. To introduce temporal variability, we apply random shuffling to the frame order with a probability of 0.5. Specifically, we generate a random permutation , where denotes the set of all permutations of T elements, and reorder the frames accordingly to obtain the augmented sequence . This process encourages the model to learn temporal-invariant features, thereby improving its robustness to dynamic motion patterns.

-

3D Keypoint Rotation: To account for variations in target orientation, we apply spatial transformations to the groundtruth 3D keypoints. With a probability of 0.5, we sample a random rotation angle from the interval and rotate the keypoints around the vertical (y) axis. The rotation is implemented using the standard 3D rotation matrix for the y-axisThe transformed keypoints are then computed as , where represents the original keypoint coordinates, and corresponds to the number of keypoints. This transformation maintains the skeletal structure while enhancing the model’s adaptability to changes in target orientation.

4.2. Feature Extractor

4.3. Fusion and Initial Estimation

4.4. Localization Optimizer

4.4.1. Graph-Based Encoding

4.5. Constraint Projection

4.5.1. Bone Length Refinement

4.5.2. Joint Angle Refinement

4.5.3. Residual Fusion

4.5.4. Total Loss

4.6. Evaluation Metrics

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): This metric quantifies the average L1 distance between the predicted keypoints and the groundtruth keypoints across all samples, joints, and spatial coordinate dimensions .where and denote the predicted and groundtruth coordinates of the n-th keypoint in the b-th sample, along the x, y, and z axes respectively.

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): This metric measures the average L2 error between predicted and groundtruth coordinates along the three spatial dimensions.

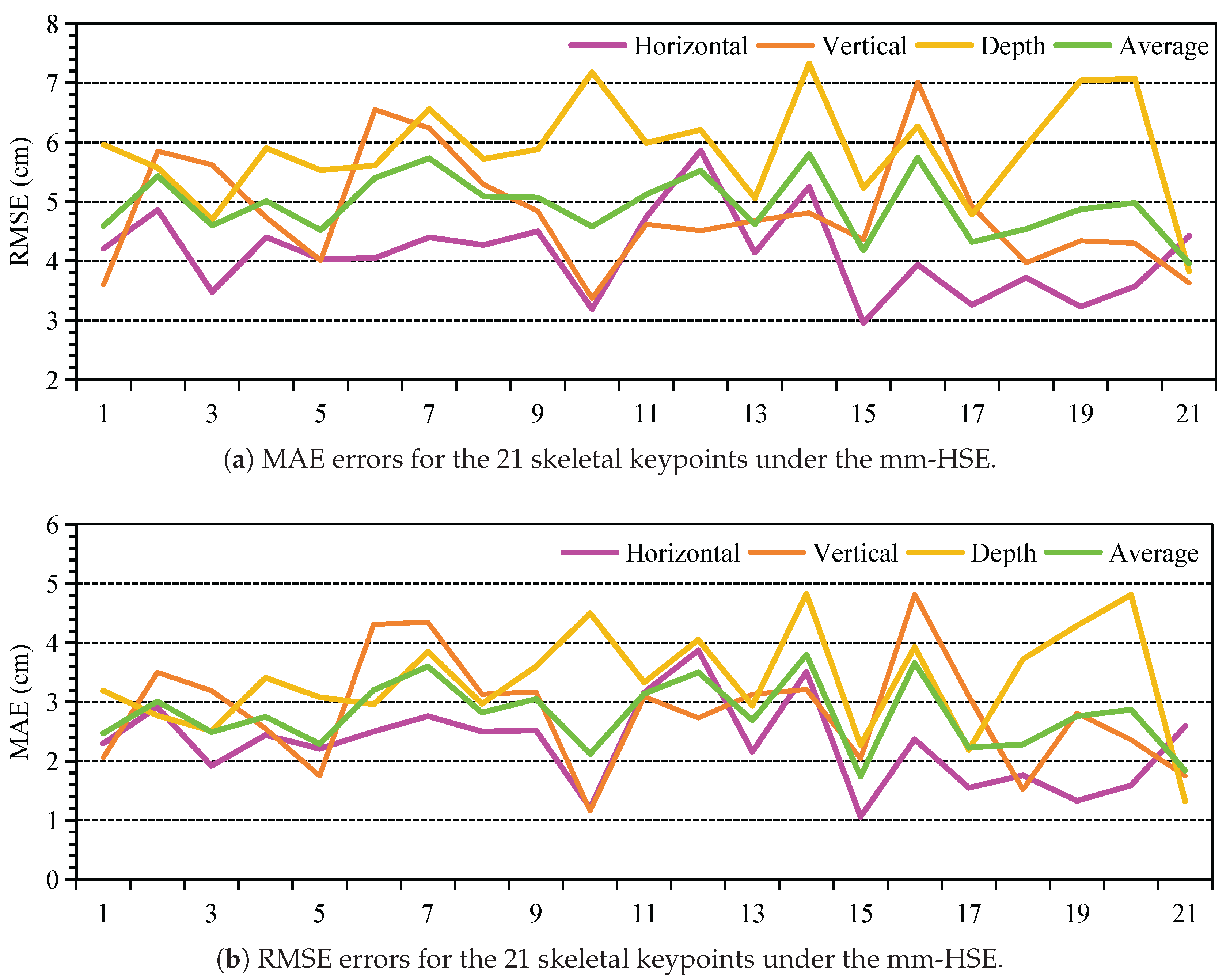

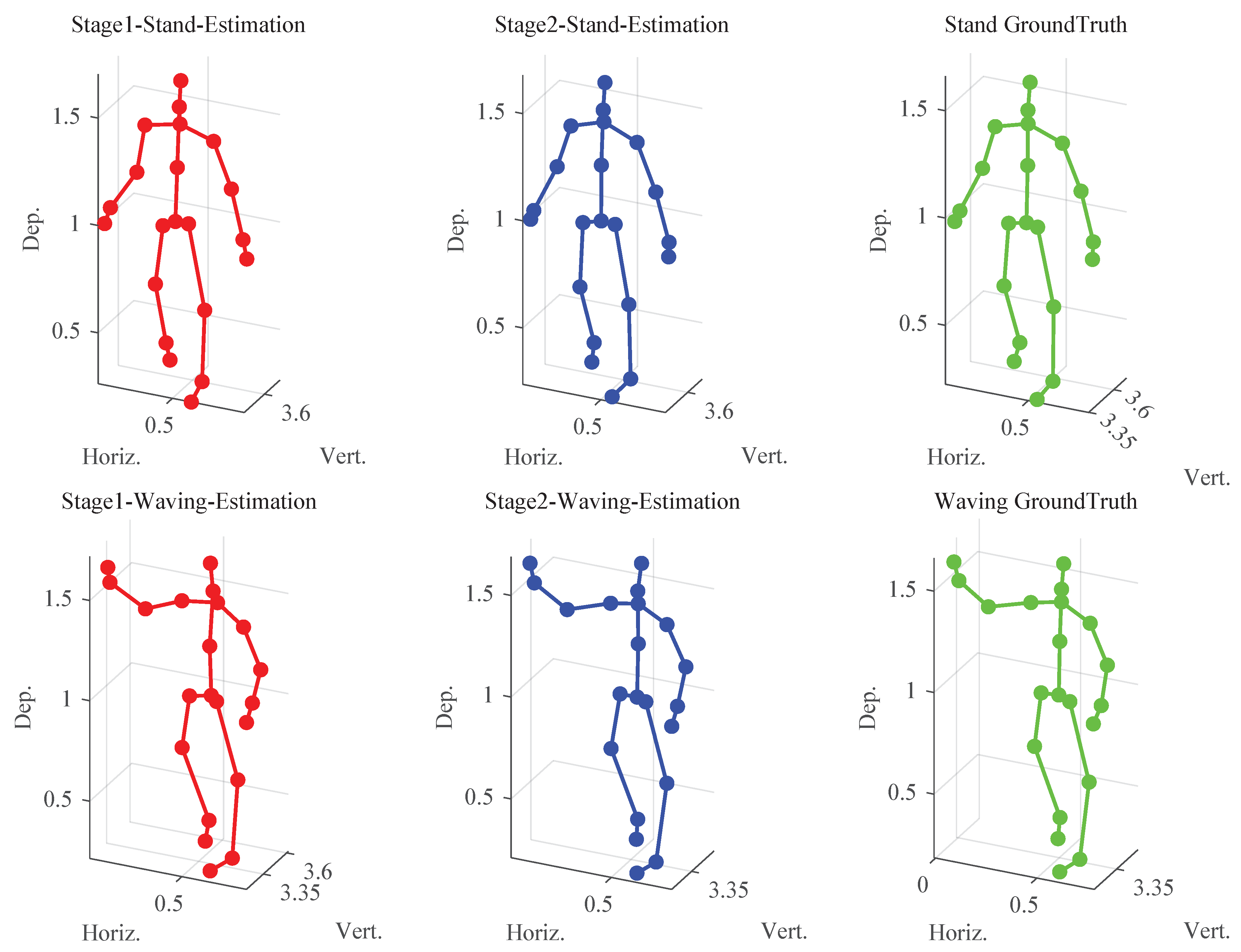

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

5.1. Experimental Setup

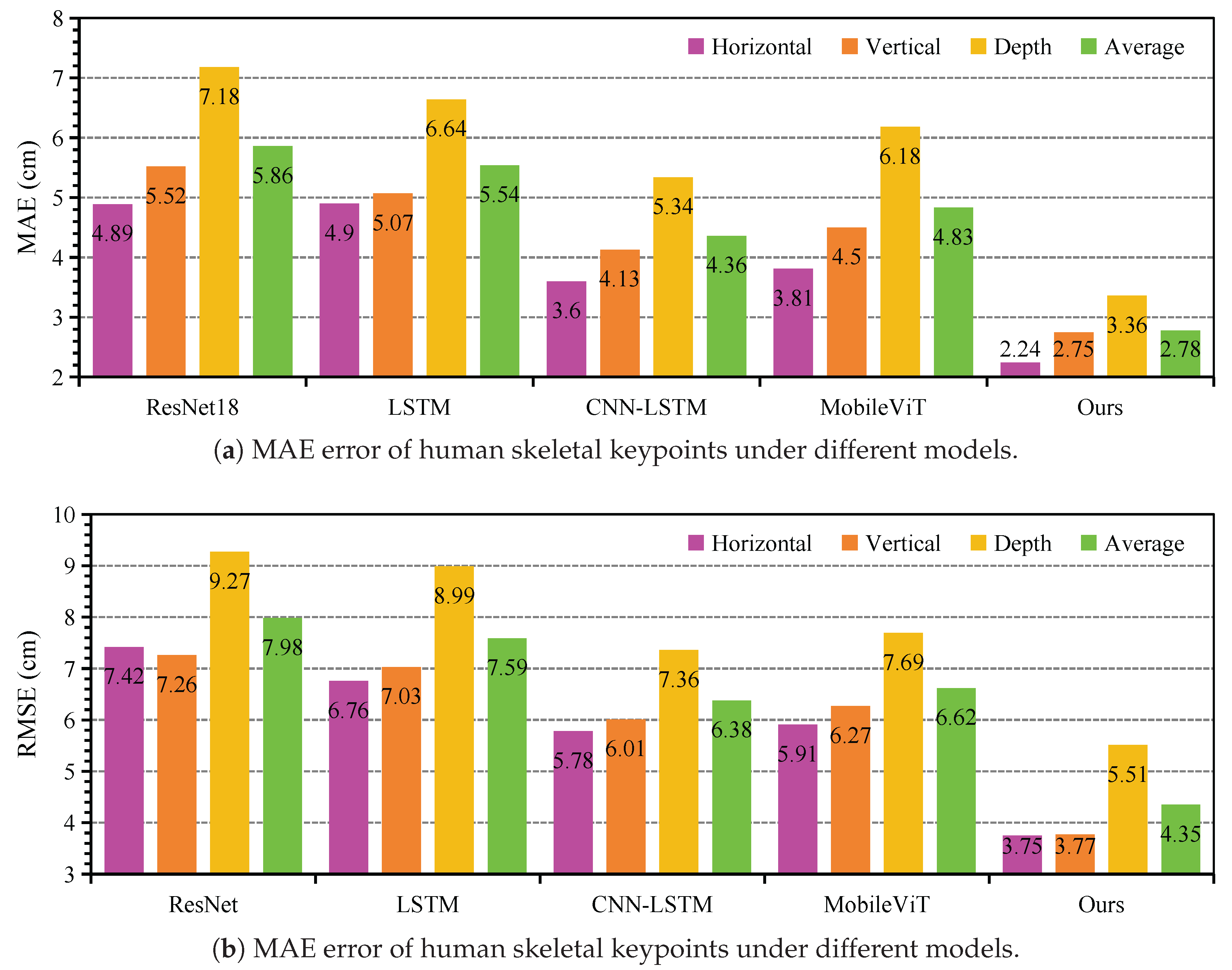

5.2. Comparative experiment

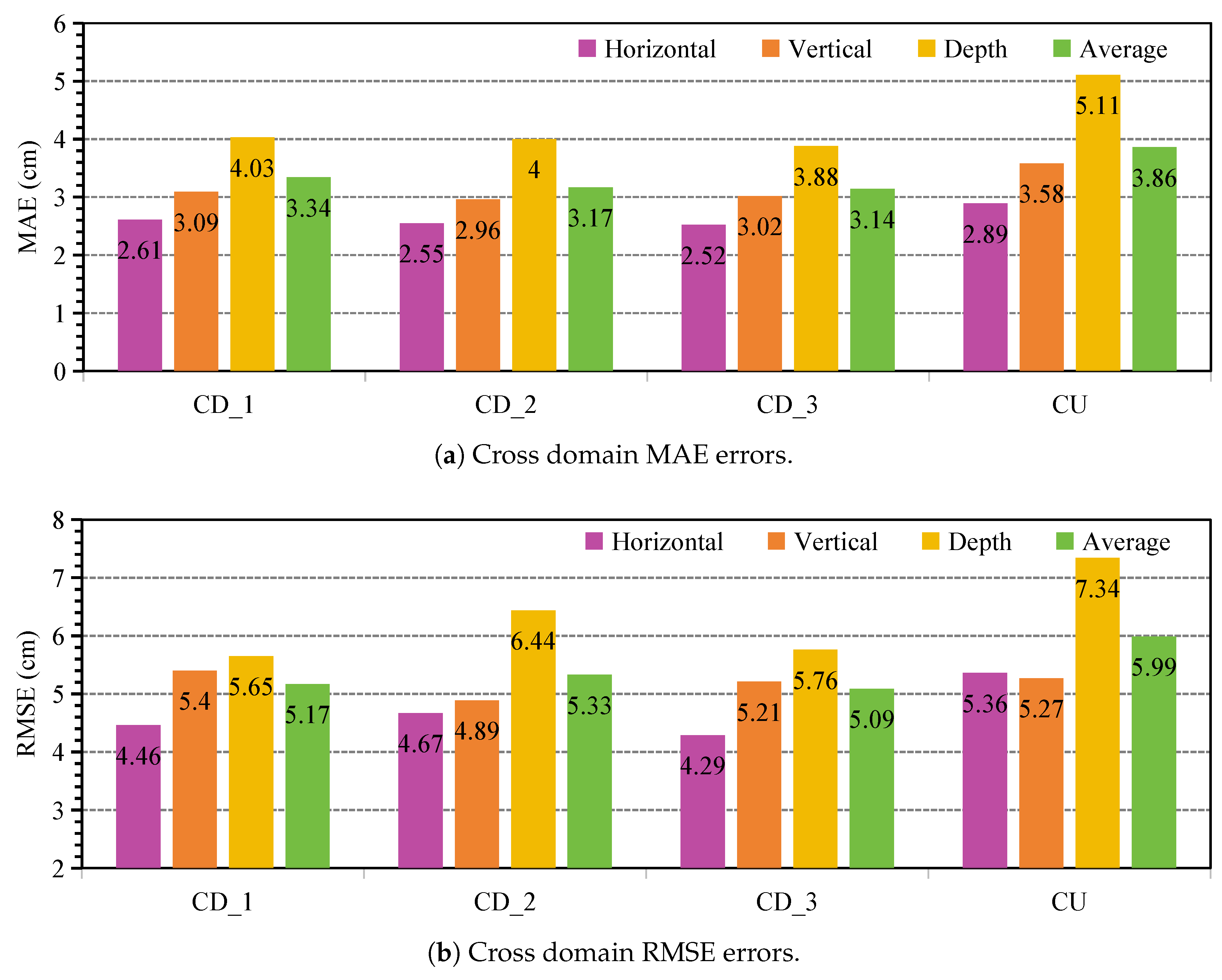

5.3. Cross-Domain Experiment

5.4. Ablation Experiment

5.4.1. The Influence of the Module

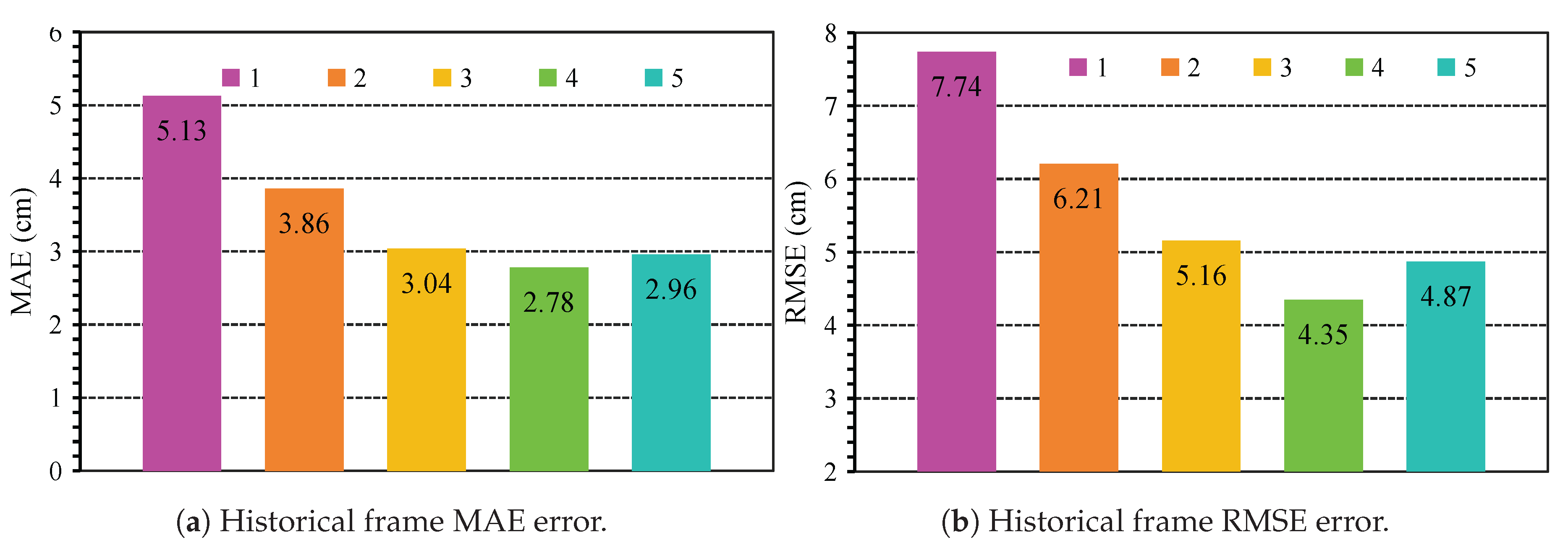

5.4.2. Impact of Historical Frame Amount

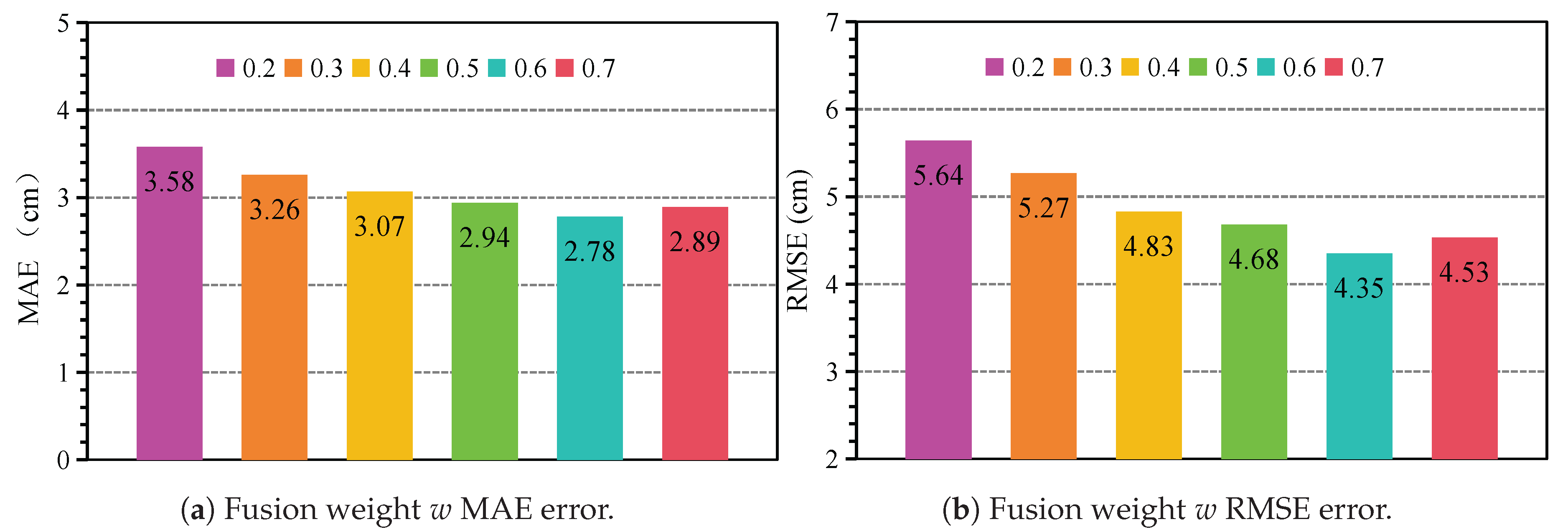

5.4.3. Impact of Fusion Weigh Size

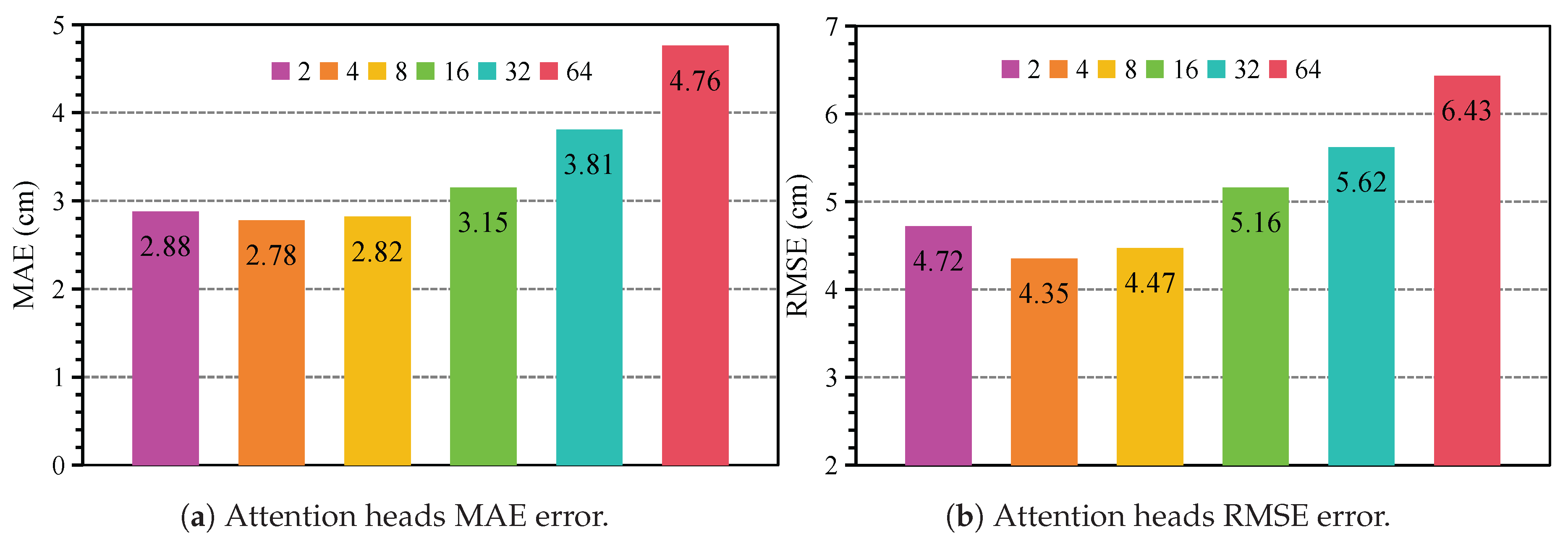

5.4.4. Impact of Attention Head Amount

6. Conclusions

- Depth Estimation Refinement and Lightweight Real-Time Deployment. In current HSE systems, the relatively low accuracy of depth (z-axis) estimation limits the overall quality of skeletal reconstruction. To overcome this, future work will explore incorporating more diverse datasets and using larger-capacity neural networks to improve depth estimation. To enable real-time performance and flexible deployment in practical scenarios, we will also optimize the network via model pruning, quantization, and hardware-aware adaptation. These techniques aim to reduce model size and latency, supporting lightweight deployment on edge devices for real-time skeletal tracking under limited computational resources.

- Deployment in more diverse scenes and action categories. To enhance the applicability of mm-HSE, we plan to extend its deployment to a wider array of scenarios and action categories. Specifically, we aim to adapt the model for diverse real-world environments, including cluttered indoor spaces and dynamic outdoor settings, while supporting a broader spectrum of motion types, such as sitting, falling, and dancing. These advancements will enable robust full-body tracking in unconstrained applications, including smart healthcare, surveillance, and human-robot interaction.

- Integration with vision language models and large-scale heterogeneous data. We plan to explore the integration of radar signals with pre-trained vision–language models to enhance semantic reasoning and long-range contextual modeling. Additionally, we will construct a cross-domain and cross-user benchmark by combining open-source and self-collected radar datasets, thereby promoting more generalizable learning and robust adaptation in practical multimodal settings.

- High-precision evaluation with motion capture systems and application in gaming. To further improve the rigor and reliability of model evaluation, we plan to integrate our radar-based setup with a professional motion capture system (e.g., VICON). This integration will enable precise synchronization and provide accurate 3D skeletal ground-truth data via standardized formats such as C3D files or outputs from Nexus software. Such ground-truth references are widely accepted in the research community and will serve as a robust benchmark for performance assessment. In addition, given the centimeter-level joint accuracy and the incorporation of anatomical constraints in mm-HSE, we will investigate its potential for low-cost, lighting-invariant motion capture in game development scenarios—particularly where traditional camera-based systems are impractical or unreliable.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Gao, F. A Sliding Window-Based CNN-BiGRU Approach for Human Skeletal Pose Estimation Using mmWave Radar. Sensors 2025, 25. [CrossRef].

- Cao, Z.; Ding, W.; Chen, R.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, G. A Joint Global–Local Network for Human Pose Estimation With Millimeter Wave Radar. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 434–446. [CrossRef].

- Zhang, J.; Xi, R.; He, Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, W.; Na, X.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Gu, T. A survey of mmWave-based human sensing: Technology, platforms and applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 2052–2087. [CrossRef].

- Kong, H.; Huang, C.; Yu, J.; Shen, X. A Survey of mmWave Radar-Based Sensing in Autonomous Vehicles, Smart Homes and Industry. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 463–508. [CrossRef].

- Wang, Z.; Ma, M.; Feng, X.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Guo, Y.; Chen, D. Skeleton-Based Human Pose Recognition Using Channel State Information: A Survey. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef].

- Chen, W.; Yu, C.; Tu, C.; Lyu, Z.; Tang, J.; Ou, S.; Fu, Y.; Xue, Z. A Survey on Hand Pose Estimation with Wearable Sensors and Computer-Vision-Based Methods. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef].

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Yin, Z.; Hossain, M.S.B.; Choi, H.; Guo, Z. Wearable motion capture: Reconstructing and predicting 3d human poses from wearable sensors. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 5345–5356. [CrossRef].

- Mehta, D.; Sridhar, S.; Sotnychenko, O.; Rhodin, H.; Shafiei, M.; Seidel, H.P.; Xu, W.; Casas, D.; Theobalt, C. VNect: real-time 3D human pose estimation with a single RGB camera. ACM Trans. Graph. 2017, 36. [CrossRef].

- Jain, H.P.; Subramanian, A.; Das, S.; Mittal, A. Real-Time Upper-Body Human Pose Estimation Using a Depth Camera. In Proceedings of the Proc. 5th Comput. Vis. Comput. Graph. Collab. Tech.; Gagalowicz, A.; Philips, W., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 227–238. [CrossRef].

- Ren, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J. GoPose: 3D Human Pose Estimation Using WiFi. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2022, 6. [CrossRef].

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, H.; Yuan, S.; Zou, H.; Xie, L.; Yang, J. Metafi++: Wifi-enabled transformer-based human pose estimation for metaverse avatar simulation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 14128–14136. [CrossRef].

- Singh, A.D.; Sandha, S.S.; Garcia, L.; Srivastava, M. RadHAR: Human Activity Recognition from Point Clouds Generated through a Millimeter-wave Radar. In Proceedings of the Proc. 3rd ACM Workshop Millimeter-Wave Netw. Sens. Syst., New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 51–56. [CrossRef].

- An, S.; Ogras, U.Y. MARS: mmWave-based Assistive Rehabilitation System for Smart Healthcare. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2021, 20. [CrossRef].

- Xue, H.; Ju, Y.; Miao, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, A.; Su, L. mmMesh: towards 3D real-time dynamic human mesh construction using millimeter-wave. In Proceedings of the Proc. 19th Annu. Int. Conf. Mobile Syst. Appl. Serv., New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 269–282. [CrossRef].

- Cao, Z.; Mei, G.; Guo, X.; Wang, G. Virteach: mmwave radar point-cloud-based pose estimation with virtual data as a teacher. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 17615–17628. [CrossRef].

- Sengupta, A.; Cao, S. mmpose-nlp: A natural language processing approach to precise skeletal pose estimation using mmwave radars. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 8418–8429. [CrossRef].

- Shi, X.; Ohtsuki, T. A Robust Multi-Frame mmWave Radar Point Cloud-Based Human Skeleton Estimation Approach with Point Cloud Reliability Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE SENSORS, 2023, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef].

- Xie, L.; Li, H.; Tian, J.; Zhao, Q.; Shiraishi, M.; Ide, K.; Yoshioka, T.; Konno, T. MiKey: Human Key-points Detection Using Millimeter Wave Radar. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE WCNC, 2024, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef].

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Ni, H.; Mao, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, W.; Han, J. mmHPE: Robust Multi-Scale 3D Human Pose Estimation Using a Single mmWave Radar. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 1032–1046. [CrossRef].

- Hu, S.; Cao, S.; Toosizadeh, N.; Barton, J.; Hector, M.G.; Fain, M.J. mmPose-FK: A forward kinematics approach to dynamic skeletal pose estimation using mmWave radars. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 6469–6481. [CrossRef].

- Zhao, M.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, H.; Alsheikh, M.A.; Li, T.; Hristov, R.; Kabelac, Z.; Katabi, D.; Torralba, A. RF-based 3D skeletons. In Proceedings of the Proc. Conf. ACM Spec. Interest Group Data Commun., New York, NY, USA, 2018; SIGCOMM ’18, p. 267–281. [CrossRef].

- Xie, C.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Z.; Yu, C.; Hu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Chen, Y. Accurate Human Pose Estimation using RF Signals. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE 24th Int. Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing, 2022, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef].

- Lee, S.P.; Kini, N.P.; Peng, W.H.; Ma, C.W.; Hwang, J.N. HuPR: A Benchmark for Human Pose Estimation Using Millimeter Wave Radar. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE/CVF Winter Conf. Appl. Comput. Vis., 2023, pp. 5704–5713. [CrossRef].

- Rahman, M.M.; Martelli, D.; Gurbuz, S.Z. Radar-Based Human Skeleton Estimation with CNN-LSTM Network Trained with Limited Data. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE EMBS Int. Conf. Biomed. Health Inform., 2023, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef].

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., 2016, pp. 770–778. [CrossRef].

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [CrossRef].

- Kim, T.Y.; Cho, S.B. Predicting residential energy consumption using CNN-LSTM neural networks. Energy 2019, 182, 72–81. [CrossRef].

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. Mobilevit: light-weight, general-purpose, and mobile-friendly vision transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.02178 2021. [CrossRef].

- Chen, V.; Li, F.; Ho, S.S.; Wechsler, H. Micro-Doppler effect in radar: phenomenon, model, and simulation study. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2006, 42, 2–21. [CrossRef].

| Symbol | Parameter | IWR1642BOOST | IWR6843ISK |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting Frequency | 77GHz | 60GHz | |

| B | Effective Bandwidth | 3.001GHz | 3.001GHz |

| Number of TX Antennas | 2 | 3 | |

| Number of RX Antennas | 4 | 4 | |

| Number of Samples per Chirp | 256 | 256 | |

| Number of Chirps per Frame | 32 | 32 | |

| Frame Period | 50ms | 50ms |

| Model | Data Representation | Training Set | Test Set | MAE (cm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horiz. | Vert. | Depth | Avg. | ||||

| RF-Pose3D[21] | Heatmap | 127080 | 423360 | 4.9 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.37 |

| RPM[22] | Heatmap | 278480 | 69620 | – | – | – | 5.71 |

| mmPose[20] | RGB Image | 32000 | 1700 | 7.5 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 4.47 |

| HuPR[23] | VRADE Heatmap | 115800 | 12600 | – | – | – | 6.82 |

| mm-HSE | Heatmap | 27000 | 3000 | 2.24 | 2.75 | 3.36 | 2.78 |

| Data Aug | Stage1 | Fusion | Stage2 | MAE (cm) | RMSE (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | 7.34 | 9.86 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 5.86 | 8.04 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4.62 | 7.19 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3.84 | 5.83 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2.78 | 4.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).