1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women under 40 years old [

1]. Up to 12% of malignancies in this patient group occur in

BRCA (Breast Cancer Gene) pathogenic-variant carriers [

2]. Pathogenic variants in the

BRCA 1 and

BRCA 2 genes, belonging to the category of DNA double-strand-break repair genes, place female carriers at risk of developing several malignancies, of which breast or ovarian cancers are the most significant [

3]. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, more than 60% of women with a pathogenic germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 are projected to develop breast cancer over the course of their lifetime [

4]. Breast neoplasia diagnosed in these populations is usually more aggressive than in BRCA-wildtype females, with BRCA1 mutation often being associated with triple-negative subtypes [

5]. Breast cancer often occurs at a younger age in this population, frequently before parental project completion [

6].

In recent years, there has been a growing number of studies focusing on BRCA-associated breast cancer. These studies cover molecular diagnosis, genetic testing, management of early or metastatic carcinoma, management of long-survival patients for their risk of second primary malignancy, surgical procedures, and clinical follow-up [

7]. With improved life expectancy in females with BRCA-associated breast cancer [

8], fertility and fertility preservation have become highly relevant topics in this specific oncological field.

Survival alone is no longer the standard of care in oncology in the 21st century; instead, successful reintegration into daily life should be the ultimate goal of multimodal treatment [

9,

10].

While pregnancy has been proven to be safe in women with breast cancer history overall [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], little data are available regarding a possible detrimental impact on the prognosis for the subset of patients carrying

BRCA mutations [

11].

Consequently, this study scrutinized the influence of the BRCA mutation status of breast cancer patients on reproductive outcomes in a population of Romanian women. To our knowledge, this analysis is among the first in Romania to investigate the impact of pregnancy on breast cancer outcomes in women carrying mutations in the BRCA germline while also reporting pregnancy, fetal, and obstetric outcomes.

2. Study Design and Patients

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at a single tertiary care center in Romania, focusing on women with BRCA-mutated breast cancer. Eligible participants were aged 40 or younger at diagnosis and had been treated for stage I to III breast cancer between 1995 and 2017. Only those with confirmed pathogenic germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 were included. The exclusion criteria encompassed individuals with BRCA variants of uncertain significance, a history of ovarian or other non-breast malignancies, noninvasive breast cancer, de novo stage IV disease, lack of follow-up data, or no post-treatment pregnancy information. Patients who were BRCA mutation carriers but had not developed breast cancer were also excluded. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board, and all participants gave informed consent prior to inclusion. Clinical data were gathered on tumor characteristics, treatment received, BRCA mutation type, reproductive outcomes, cancer recurrence, survival, and post-treatment pregnancies. All of the patients were monitored up to the present.

3. Statistical Analysis

Pregnancy, fetal, and obstetric outcomes were primary endpoints. Descriptive analysis was used to evaluate the two groups while considering the time interval between oncological diagnosis and the reproductive history, along with its particularities and outcomes.

All of the data from the study were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and formatted using Microsoft Office Excel/Word 2021. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test for the normal distribution of the analyzed quantitative variables, with these being written as averages with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges. Absolute values or percentages were used in qualitative variables, and differences between groups were tested using Fisher’s exact test. Z-tests with Bonferroni correction were applied for more precise results in the contingency tables.

Mann–Whitney U tests were used to test the quantitative independent variables with non-parametric distribution. Student T-tests were used to test quantitative independent variables with a normal distribution between groups. Survival analyses, including overall survival, disease-free survival, progression-free survival, and time from diagnosis to pregnancy, were conducted using the Kaplan–Meier curve. The differences in survival times between BRCA gene groups were determined with Tarone–Ware or Log-rank tests.

4. Results

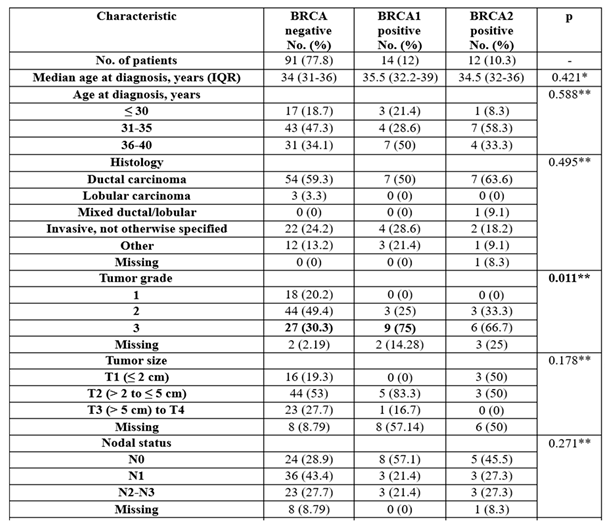

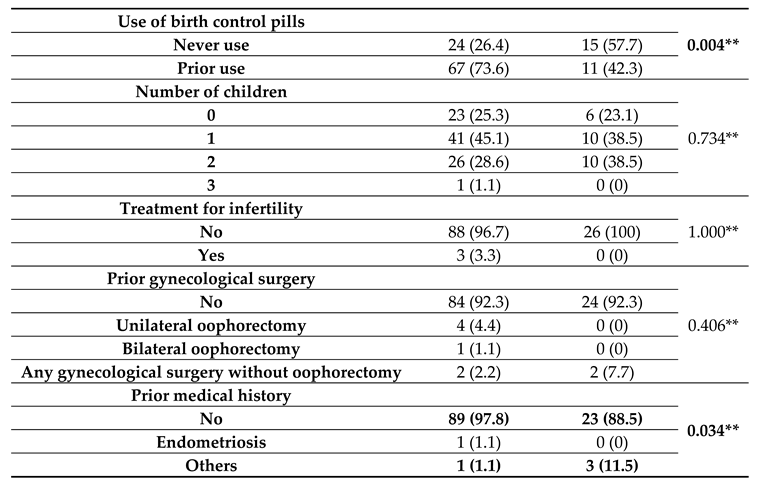

One hundred and seventeen young patients diagnosed with breast cancer were eligible to be included in the current analysis, of whom 15 had at least one pregnancy after breast cancer treatment; 11 were BRCA-wildtype and 4 were BRCA-positive (2 patients were BRCA1-positive and 2 patients were BRCA2-positive). In our study, 4 out of 15 pregnant patients in both cohorts opted for induced abortion. The baseline patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics are listed in

Table 1.

The age at diagnosis was not significant between groups (p=0.421/p=0.588). Most patients were between 31 and 35 or 36 and 40, with the median age being 34 in the BRCA-negative group and 35.5 in the BRCA1 group/34.5 in the BRCA2-positive group. Thirteen patients out of 15 in the pregnancy cohort were younger than 35 years at diagnosis.

The histological subtypes were not significantly different between groups (p=0.495), with most of the patients having a ductal carcinoma (59.3%—BRCA-negative group, 50%—BRCA1 group, 63.6%—BRCA2 group).

The tumor grade was particularly distinct between groups (p=0.001), with BRCA1 patients being more associated with poorly differentiated tumors (75% vs. 30.3%).

Hormone receptor status was significantly different between groups (p<0.001), with BRCA1 patients being more frequently ER- and PR-negative (85.7% vs. 18.9%/27.3%), while BRCA negative patients or BRCA2 patients were more frequently ER- and/or PR-positive (81.1%/72.7% vs. 14.3%).

HER2 status was not significantly different between groups (p=0.052), with most of the patients being HER2-negative (73.3%—BRCA-negative group, 92.9%—BRCA1 group, 100%—BRCA2 group).

The usage of chemotherapy was not significantly different between groups (p=0.228); most of the patients had chemotherapy (92.1%—BRCA negative group, 100%—BRCA1 group, 83.3%—BRCA2 group).

The usage of endocrine therapy was significantly different between groups (p<0.001), with BRCA-negative patients having more frequent endocrine therapy than BRCA1 patients (83.3% vs. 28.6%), while BRCA1 patients had less frequent endocrine therapy (71.4% vs. 16.7%).

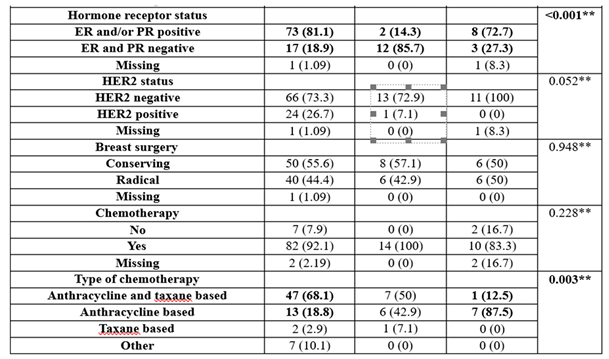

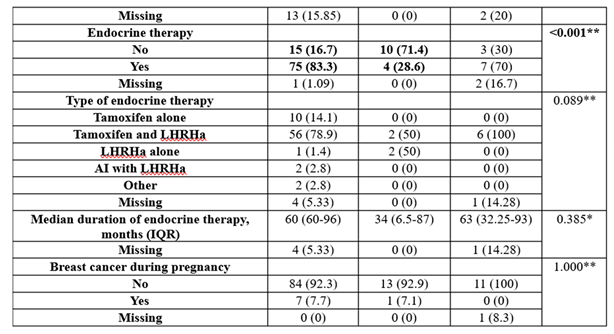

For patients with medical history characteristics grouped by BRCA gene existence (listed in

Table 2), it was observed that usage of birth control pills was significantly different between groups (

p=0.004), with BRCA-negative patients more frequently using birth control (73.6% vs. 42.3%) while BRCA-positive patients less frequently used birth control (57.7% vs. 26.4%). Prior medical history was significantly different between groups (

p=0.034); BRCA-negative patients were more associated with no medical history (97.8% vs. 88.5%), while BRCA-positive patients were more associated with other comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus or systemic lupus erythematosus) (11.5% vs. 1.1%).

5. Reproductive Outcomes

The data in

Table 3 show the pregnancy, fetal, and obstetric outcomes in the pregnancy cohort grouped by BRCA gene status. There were 15 pregnant patients analyzed, with 11 being BRCA-wildtype and 4 being BRCA-positive (2 patients were BRCA1-positive and 2 patients were BRCA2-positive). All of the analyzed tests had a low/very low significance value due to the small number of pregnant patients.

The results show the following:

Differences in time from diagnosis to pregnancy were insignificant between groups (p=0.337), with the median period being 6 years in the BRCA-negative group, 2.5 years in the BRCA1 group, and 4.5 years in the BRCA2 group. The pregnancy interval was also not significant between groups (p=0.328); most of the patients in the BRCA-negative group had more than 5 years from diagnosis to pregnancy (54.5%), while most of the BRCA1 patients and BRCA2 patients had less than 2 years from diagnosis to pregnancy (50%/50%), but the differences observed could not be proven to be significant.

The pregnancy outcomes were not significant between groups (p=0.292). Most of the patients had one live birth: 63.6%—BRCA-negative group, 100%—BRCA1 group, 0%—BRCA2 group).

The timing of delivery was not significant between groups (p=0.417). Most of the patients delivered the pregnancy at term (85.7%—BRCA-negative group, 50%—BRCA1-positive group).

For the rate of breastfeeding, a tendency towards statistical significance (p=0.083) was observed in the direction of breastfeeding being more present to the BRCA-negative group (85.7% vs. 0%), but the significance could not be demonstrated because of the limited number of analyzed patients, as the median duration of breastfeeding in the BRCA-negative group was 6 months (IQR = 1-18 months).

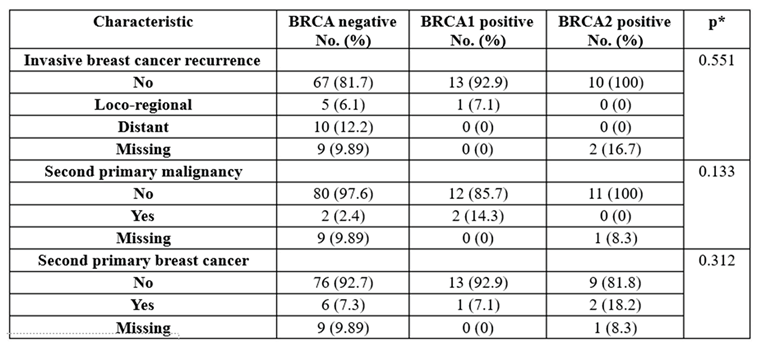

The data in

Table 4 show the patient recurrence distribution grouped by the existence of the BRCA gene. The results show the following:

The rate of recurrence was not significant between groups (p=0.551). Most of the patients did not have any recurrence (81.7%—BRCA-negative, 92.9%—BRCA1 group, 100%—BRCA2 group).

The rate of second primary malignancy was not significant between groups (p=0.133). Most of the patients did not have any second primary malignancies (97.6%—BRCA-negative, 85.7%—BRCA1 group, 100%—BRCA-positive).

The rate of second primary breast cancer was not significant between groups (p=0.312). Most of the patients did not have any second primary breast cancer (92.7%—BRCA-negative, 92.9%—BRCA1 group, 81.8%—BRCA2 group).

6. Discussion

This study is the first in Romania to precisely assess the safety of pregnancy in young breast cancer patients with BRCA mutation. The analysis included 117 young breast cancer patients, of whom 15 had at least one pregnancy after their diagnosis. The study found that pregnancy after breast cancer did not appear to worsen maternal prognosis and was associated with favorable fetal outcomes. All patients were continuously monitored until the present.

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in young adult women [

17]. Many women diagnosed with breast cancer may still be interested in a future pregnancy, but a positive BRCA1/2 germline mutation can significantly impact reproductive decision making due to its long-term implications, including a lifetime risk of breast and ovarian cancers, an autosomal dominant condition, and preventative surgeries [

18]. In addition,

BRCA1/2 germline mutation leads to impaired DNA repair, accelerating oocyte aging and reducing the oocyte reserve by initiating oocyte apoptosis [

3]. Moreover, young patients diagnosed with breast cancer will more often fall within the criteria for genetic testing or counseling guidelines, therefore testing positive for a BRCA mutation. Most young, fit patients, especially those with TNBC, will undergo chemotherapy as part of their treatment plan, further altering their reproductive options, principally in the absence of fertility counseling beforehand. Above all, there is a sociocultural phenomenon of postponing parenthood due to the rise in effective contraception and increases in women’s education, but delayed childbirth (first child after the age of 30 years) is known to be a risk factor for breast cancer [

19].

EUROSTAT figures indicate a consistent upward trend in the age of first-time motherhood across the European Union, with the average reaching 29.3 years by 2018 [

20]. Additionally, approximately 10% of women diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 40 carry a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation [

21]. These statistics suggest that many young women in this demographic may either postpone or have not yet initiated childbearing when faced with a cancer diagnosis. This is why we have to understand that larger studies are needed to ensure that pregnancy after breast cancer in patients with germline

BRCA mutations is safe without apparent worsening of maternal prognosis. Although conflicting results can be employed, a large, statistically powered study previously demonstrated the safety of subsequent pregnancy in young breast cancer patients irrespective of estrogen-receptor status, but only in a select subgroup of early-stage breast cancer [

22].

Age at diagnosis was not significant between groups, with the median age being 34 in the BRCA-negative group, 35.5 in the BRCA1-positive group, and 34.5 in the BRCA2-positive group; 13 patients of 15 in the pregnancy cohort were younger than 35 years at diagnosis. This can be attributed to selection bias due to the fact that the cohort included patients who were tested for BRCA mutations according to national guidelines. Lambertini et al. found that BRCA1/2 carriers who became pregnant after breast cancer were usually younger and had early-stage tumors without lymph node involvement [

23]. This may reflect the "healthy mother effect"—women with better outcomes are more likely to try for pregnancy [

24]. Experts advise waiting at least two years after starting hormone therapy to finish treatment and catch early relapses [

25]. In our study, differences in time from diagnosis to pregnancy were not significant between groups, with the median period in the BRCA-negative group being 6 years, while it was 2.5 years in the BRCA1 group and 4.5 years in the BRCA2 group. The pregnancy interval was also not significant between groups, with most of the patients in the BRCA-negative group having more than 5 years from diagnosis to pregnancy (54.5%), while most of the BRCA1 patients and BRCA2 patients had less than 2 years from diagnosis to pregnancy (50%/50%), but the differences observed could not be proven to be significant.

On the basis of the last results from the POSITIVE trial [

22], no international guidelines advise against pregnancy in young women with breast cancer who completed oncological treatment [

37,

38]. As mentioned, 1 in 10 women with breast cancer diagnosed under 40 years carry a

BRCA1/2 mutation [

13], and among these patients, a higher-than-expected pregnancy rate was observed (19% in 10 years). Our results showed that the pregnancy interval was also not significant between groups; most of the patients in the BRCA-negative group had more than 5 years from diagnosis to pregnancy, while most of the BRCA1 patients and BRCA2 patients had less than 2 years from diagnosis to pregnancy (50%/50%). This may be due to a lower proportion of patients with hormone receptor-positive tumors and the younger age of the patients at diagnosis, as well as to prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy recommendation as early as possible at that time.

A key concern for these patients is the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as congenital anomalies linked to previous gonadotoxic treatments; although most studies are reassuring, some suggest higher rates of preterm birth and perinatal complications in breast cancer survivors [

39].

The effect of chemotherapy on the uterine arteries is certainly a path to be investigated, as this would bring valuable information for both obstetrics and embryo transfer during in vitro fertilization procedures. Our data show that all pregnancies in the cohort resulted in full-term deliveries, with no adverse events or congenital malformations being observed. However, other studies with larger cohorts revealed a preterm rate of 9.2% [

23,

40], which is similar to that expected in the general population (approximately 11%) [

33], and a congenital anomaly rate of 1.8% [

15], which is 3% in the general population [

41]. Prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in the BRCA-positive group made breastfeeding impossible, but it is important to note the role of breastfeeding among women with a

BRCA1 or

BRCA2 mutation. Data from one study show a protective role of breastfeeding against

BRCA1-mutated breast cancer, but there is no protection for those with

BRCA2 mutations. However, women with a

BRCA mutation should be informed of the benefits of breastfeeding in terms of reducing breast cancer risk [

42]

In our study, 4 out of 15 pregnant patients in both cohorts opted for induced abortion. The reason for this procedure was that patients did not expect to become pregnant after their oncological treatment. However, we have to inform the patients that safe and reliable options for contraception are available for women who do not desire conception.

While there is much research behind these studies, many physicians remain concerned about a potential relapse of breast cancer in germline BRCA mutation patients in the setting of pregnancy. The POSITIVE trial results demonstrated the safety of subsequent pregnancy in patients with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer, but only for select subgroups of early-stage disease, and with a lack of long-term data. There is a lack of studies regarding pregnancy in patients with a positive germline mutation. Even so, recent studies demonstrated a similar long-term prognosis for BRCAmut patients when compared with BRCA-wildtype cohorts. Therefore, similar guidelines and precautions regarding pregnancy should be applied to these groups. Of course, our study should be considered in the context of its limitations, which include the retrospective nature, some missing information on the course, and the relatively small number of patients included in both cohorts, with an impact on the statistical results.

To conclude, larger, prospective, multicentric studies are needed in order to confirm the safety of pregnancy in BRCA-mutated breast cancer patients. The present analysis, although limited by selection bias and the small number of patients, did not associate BRCA mutation with a worse prognosis in the setting of pregnancy, nor did pregnancy outcomes seem to be affected by the BRCA status. These findings could stand as a pillar for further investigations and could have an important impact on healthcare providers involved in counseling young BRCAmut patients with breast cancer who are concerned about the feasibility and safety of future conception.

7. Conclusions

This retrospective study is the first in Romania to evaluate the reproductive outcomes in young breast cancer patients with BRCA mutations. Our findings indicate that pregnancy after breast cancer treatment does not appear to adversely affect maternal prognosis, even in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Although the statistical significance of the obtained results was limited by the small sample size, reproductive outcomes such as live birth rates, breastfeeding, and delivery timing were comparable between BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative patients.

Importantly, BRCA status did not correlate with increased cancer recurrence or adverse obstetric outcomes in this cohort. These results support the notion that pregnancy is feasible and likely safe after breast cancer in BRCA mutation carriers, reinforcing current international guidelines. However, larger multicenter prospective studies are warranted to confirm these findings and provide stronger evidence to guide clinical practice in fertility counseling and cancer survivorship care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Cristina Tanase-Damian and Diana Loreta Paun; Methodology, Nicoleta Antone and Alexandru Eniu; Formal analysis, Eliza Belea and Carina Crisan; Investigation, Ioan Tanase and Anca Coricovac; Resources, Patriciu Achimas-Cadariu; Writing—original draft, Cristina Tanase-Damian; Writing—review and editing, Nicoleta Antone. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Oncology “Prof. Dr. Ion Chiricuta”, Cluj Napoca, Romania (Nr 245/27.09.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Breast cancer statistics | World Cancer Research Fund [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 7]. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/breast-cancer-statistics/.

- Rosenberg SM, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM, Gelber S, Schapira L, Come S, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Testing in Young Women With Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2016 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Dec 14];2(6):730–6. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2490541.

- Turan V, Oktay K. BRCA-related ATM-mediated DNA double-strand break repair and ovarian aging. Hum Reprod Update [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2021 Jun 17];26(1):43–57. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31822904/.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network - Home [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 20]. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/.

- Chen H, Wu J, Zhang Z, Tang Y, Li X, Liu S, et al. Association Between BRCA Status and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol [Internet]. 2018 Aug 21 [cited 2024 Oct 14];9(AUG). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30186165/.

- Londero AP, Bertozzi S, Xholli A, Cedolini C, Cagnacci A. Breast cancer and the steadily increasing maternal age: are they colliding? BMC Womens Health [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Apr 7];24(1):1–11. Available online: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-024-03138-4.

- Dubsky P, Jackisch C, Im SA, Hunt KK, Li CF, Unger S, et al. BRCA genetic testing and counseling in breast cancer: how do we meet our patients’ needs? npj Breast Cancer 2024 10:1 [Internet]. 2024 Sep 5 [cited 2024 Oct 3];10(1):1–12. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41523-024-00686-8.

- Fasching, P.A. Breast cancer in young women: do BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations matter? Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2018 Feb 1 [cited 2024 Oct 14];19(2):150–1. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S1470204518300081/fulltext.

- Peate M, Meiser B, Hickey M, Friedlander M. The fertility-related concerns, needs and preferences of younger women with breast cancer: A systematic review [Internet]. Vol. 116, Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat; 2009 [cited 2021 Jun 17]. p. 215–23. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19390962/.

- Ruddy KJ, Gelber SI, Tamimi RM, Ginsburg ES, Schapira L, Come SE, et al. Prospective study of fertility concerns and preservation strategies in young women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology [Internet]. 2014 Apr 10 [cited 2021 Jun 17];32(11):1151–6. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24567428/.

- Lambertini M, Goldrat O, Toss A, Azim HA, Peccatori FA, Ignatiadis M, et al. Fertility and pregnancy issues in BRCA-mutated breast cancer patients. Cancer Treat Rev [Internet]. 2017 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];59:61–70. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28750297/.

- Iqbal J, Amir E, Rochon PA, Giannakeas V, Sun P, Narod SA. Association of the Timing of Pregnancy With Survival in Women With Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2017 May 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];3(5):659–65. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28278319/.

- Lambertini M, Kroman N, Ameye L, Cordoba O, Pinto A, Benedetti G, et al. Long-term Safety of Pregnancy Following Breast Cancer According to Estrogen Receptor Status. J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. 2018 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];110(4):426–9. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29087485/.

- Lambertini M, Martel S, Campbell C, Guillaume S, Hilbers FS, Schuehly U, et al. Pregnancies during and after trastuzumab and/or lapatinib in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive early breast cancer: Analysis from the NeoALTTO (BIG 1-06) and ALTTO (BIG 2-06) trials. Cancer [Internet]. 2019 Jan 15 [cited 2023 Dec 15];125(2):307–16. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30335191/ Reference class.

- Azim HA, Santoro L, Pavlidis N, Gelber S, Kroman N, Azim H, et al. Safety of pregnancy following breast cancer diagnosis: A meta-analysis of 14 studies. Eur J Cancer [Internet]. 2011 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];47(1):74–83. Available online: http://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959804910008725/fulltext.

- Azim HA, Kroman N, Paesmans M, Gelber S, Rotmensz N, Ameye L, et al. Prognostic impact of pregnancy after breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status: a multicenter retrospective study. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2013 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];31(1):73–9. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23169515/.

- Ellington TD, Miller JW, Henley SJ, Wilson RJ, Wu M, Richardson LC. Trends in Breast Cancer Incidence, by Race, Ethnicity, and Age Among Women Aged ≥20 Years — United States, 1999–2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report [Internet]. 2022 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];71(2):43. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8757618/.

- Haddad JM, Robison K, Beffa L, Laprise J, ScaliaWilbur J, Raker CA, et al. Family planning in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. J Genet Couns. 2021 Dec 1;30(6):1570–81.

- Kelsey JL, Gammon MD, John EM. Reproductive factors and breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev [Internet]. 1993 [cited 2024 Nov 3];15(1):36–47. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8405211/.

- Women are having their first child at an older age - Products Eurostat News - Eurostat [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 14]. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20200515-2.

- Copson ER, Maishman TC, Tapper WJ, Cutress RI, Greville-Heygate S, Altman DG, et al. Germline BRCA mutation and outcome in young-onset breast cancer (POSH): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2018 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];19(2):169–80. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S1470204517308914/fulltext.

- Partridge AH, Niman SM, Ruggeri M, Peccatori FA, Azim HA, Colleoni M, et al. Interrupting Endocrine Therapy to Attempt Pregnancy after Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2023 May 4 [cited 2023 Dec 15];388(18):1645–56. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2212856.

- Lambertini MMP, Ameye LMP, Hamy ASMP, Zingarello AM, Poorvu PD ,md, Carrasco EM, et al. Pregnancy After Breast Cancer in Patients With Germline BRCA Mutations. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2020 Sep 10 [cited 2023 Dec 15];38(26):3012–23. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32673153/.

- Sankila R, Heinävaara S, Hakulinen T. Survival of breast cancer patients after subsequent term pregnancy: “Healthy mother effect.” Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Mar 1;170(3):818–23.

- Maksimenko J, Irmejs A, Gardovskis J. Pregnancy after breast cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Hered Cancer Clin Pract [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];20(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8781048/.

- Profile [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 15]. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/profile.

- Bayraktar S, Glück S. Systemic therapy options in BRCA mutation-associated breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2012 Sep [cited 2023 Dec 15];135(2):355–66. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22791366/.

- Cibula D, Zikan M, Dusek L, Majek O. Oral contraceptives and risk of ovarian and breast cancers in BRCA mutation carriers: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther [Internet]. 2011 Aug [cited 2023 Dec 15];11(8):1197–207. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21916573/.

- Cibula D, Gompel A, Mueck AO, La Vecchia C, Hannaford PC, Skouby SO, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of cancer. Hum Reprod Update [Internet]. 2010 Jun 12 [cited 2023 Dec 15];16(6):631–50. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20543200/.

- Cibula D, Zikan M, Dusek L, Majek O. Oral contraceptives and risk of ovarian and breast cancers in BRCA mutation carriers: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther [Internet]. 2011 Aug [cited 2023 Dec 15];11(8):1197–207. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21916573/.

- Moorman PG, Havrilesky LJ, Gierisch JM, Coeytaux RR, Lowery WJ, Urrutia RP, et al. Oral contraceptives and risk of ovarian cancer and breast cancer among high-risk women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2013 Nov 20 [cited 2023 Dec 15];31(33):4188–98. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24145348/.

- Buonomo B, Massarotti C, Dellino M, Anserini P, Ferrari A, Campanella M, et al. Reproductive issues in carriers of germline pathogenic variants in the BRCA1/2 genes: an expert meeting. BMC Med. 2021 Dec 1;19(1).

- Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, Feroce I, Bonanni B, Radice P, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: A meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer [Internet]. 2010 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];46(12):2275–84. Available online: http://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959804910003400/fulltext.

- Pasanisi P, Hédelin G, Berrino J, Chang-Claude J, Hermann S, Steel M, et al. Oral contraceptive use and BRCA penetrance: A case-only study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention [Internet]. 2009 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];18(7):2107–13. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0024.

- Kotsopoulos J, Lubinski J, Moller P, Lynch HT, Singer CF, Eng C, et al. Timing of oral contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2014 Feb 24 [cited 2023 Dec 15];143(3):579–86. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10549-013-2823-4.

- Huber D, Seitz S, Kast K, Emons G, Ortmann O. Use of oral contraceptives in BRCA mutation carriers and risk for ovarian and breast cancer: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Oct 3];301(4):875. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8494665/.

- Peccatori FA, Azim JA, Orecchia R, Hoekstra HJ, Pavlidis N, Kesic V, et al. Cancer, pregnancy and fertility: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Annals of Oncology [Internet]. 2013 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Dec 18];24(SUPPL.6):vi160–70. Available online: http://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923753419315492/fulltext.

- Paluch-Shimon S, Cardoso F, Partridge AH, Abulkhair O, Azim HA, Bianchi-Micheli G, et al. ESO–ESMO 4th International Consensus Guidelines for Breast Cancer in Young Women (BCY4). Annals of Oncology. 2020 Jun 1;31(6):674–96.

- van der Kooi ALLF, Kelsey TW, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Laven JSE, Wallace WHB, Anderson RA. Perinatal complications in female survivors of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2019 Apr 1;111:126–37.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2019 Jul 1;(346):1–8.

- Dolk H, Loane M, Garne E. The prevalence of congenital anomalies in Europe. Adv Exp Med Biol [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2023 Dec 18];686:349–64. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-90-481-9485-8_20.

- Kotsopoulos J, Lubinski J, Salmena L, Lynch HT, Kim-Sing C, Foulkes WD, et al. Breastfeeding and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Research [Internet]. 2012 Mar 9 [cited 2024 Nov 10];14(2):1–7. Available online: https://breast-cancer-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/bcr3138.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics grouped by BRCA gene existence.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics grouped by BRCA gene existence.

Table 2.

Patients’ medical history characteristics grouped by BRCA gene existence.

Table 2.

Patients’ medical history characteristics grouped by BRCA gene existence.

| Characteristic |

BRCA-negative

No. (%) |

BRCA-positive

No. (%) |

p |

| Smoking habit |

|

|

0.272** |

| Never smoker |

53 (58.2) |

16 (61.5) |

| Smoker |

29 (31.9) |

10 (38.5) |

| Former smoker |

9 (9.9) |

0 (0) |

| Age at menarche, years (IQR) |

13 (12-14) |

13 (11.87-14) |

0.279* |

| Use of birth control pills |

|

|

0.004** |

| Never use |

24 (26.4) |

15 (57.7) |

| Prior use |

67 (73.6) |

11 (42.3) |

| Number of children |

|

|

0.734** |

| 0 |

23 (25.3) |

6 (23.1) |

| 1 |

41 (45.1) |

10 (38.5) |

| 2 |

26 (28.6) |

10 (38.5) |

| 3 |

1 (1.1) |

0 (0) |

| Treatment for infertility |

|

|

1.000** |

| No |

88 (96.7) |

26 (100) |

| Yes |

3 (3.3) |

0 (0) |

| Prior gynecological surgery |

|

|

0.406** |

| No |

84 (92.3) |

24 (92.3) |

| Unilateral oophorectomy |

4 (4.4) |

0 (0) |

| Bilateral oophorectomy |

1 (1.1) |

0 (0) |

| Any gynecological surgery without oophorectomy |

2 (2.2) |

2 (7.7) |

| Prior medical history |

|

|

0.034** |

| No |

89 (97.8) |

23 (88.5) |

| Endometriosis |

1 (1.1) |

0 (0) |

| Others |

1 (1.1) |

3 (11.5) |

Table 3.

Pregnancy, fetal, and obstetric outcomes in the pregnancy cohort grouped by BRCA gene existence.

Table 3.

Pregnancy, fetal, and obstetric outcomes in the pregnancy cohort grouped by BRCA gene existence.

Table 4.

Patient recurrence distribution grouped by BRCA gene existence.

Table 4.

Patient recurrence distribution grouped by BRCA gene existence.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).