Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Lipid Metabolism Indexes And Fatty Acid Composition Of Stored Brown Rice

2.2. Effects of Stored Brown Rice on Growth Performance and Meat Quality of Broilers

2.3. Antioxidant Properties and Digestive Enzyme Analyses

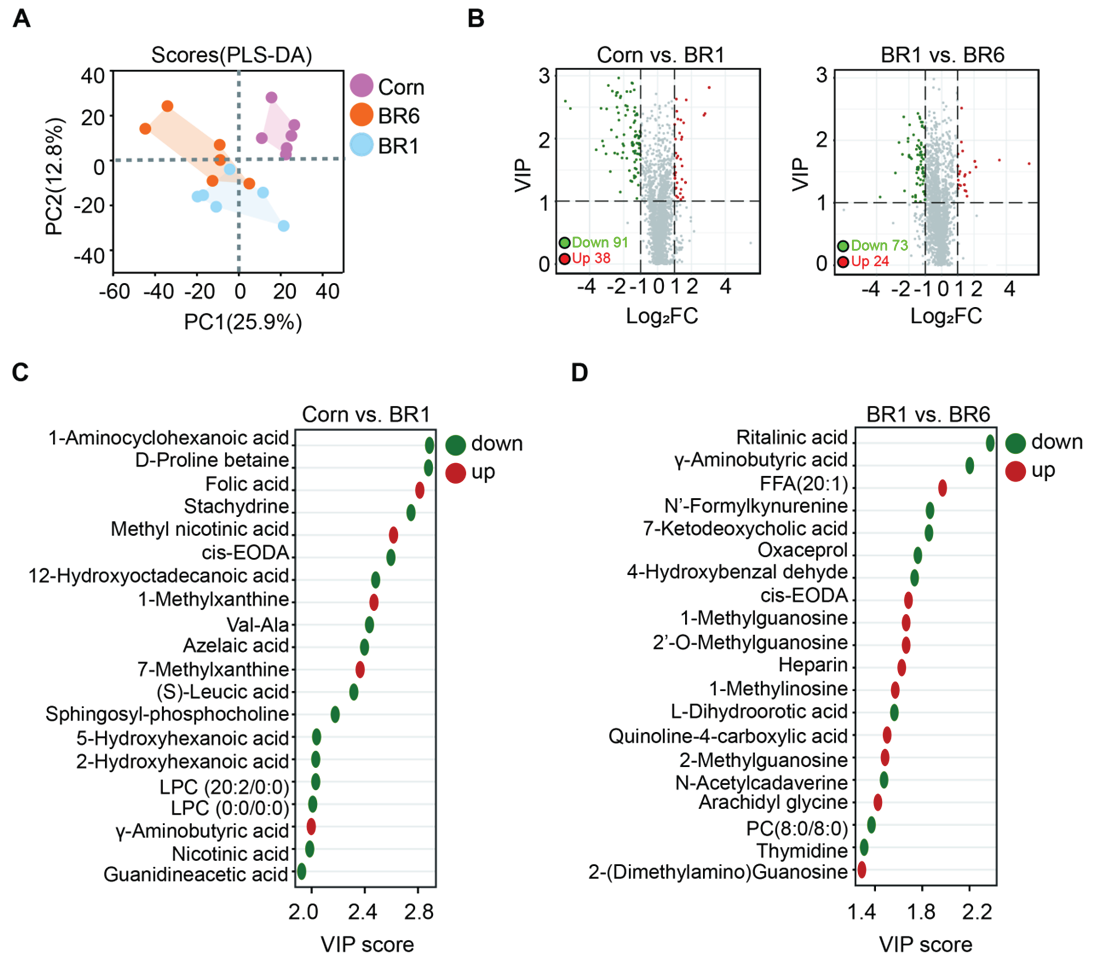

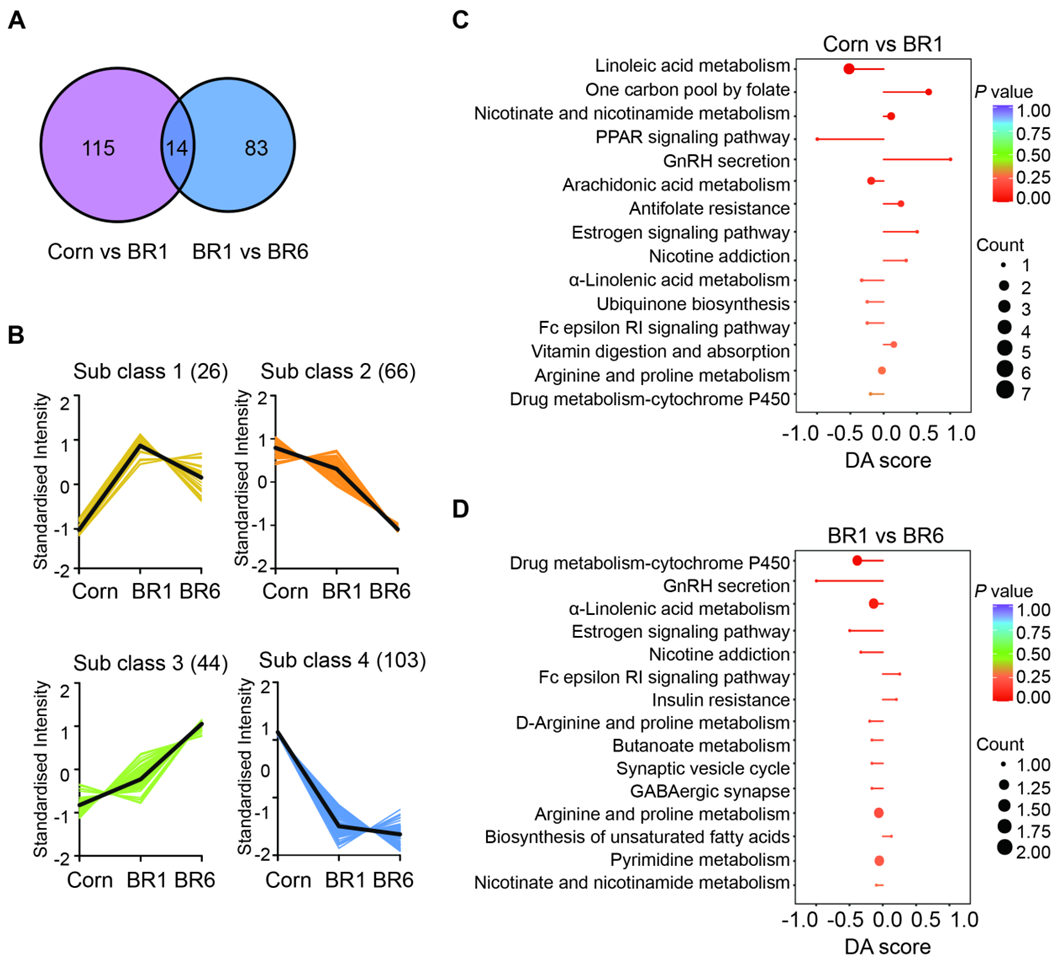

2.4. Metabolomics Analysis of Broilers Ileum

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Ethics Statement

4.2. Experimental Materials

4.3. Lipid Metabolism Indexes and Fatty Acid Composition of Stored Brown Rice

4.3. Animals and Dietary Treatments

4.4. Performance Measurement and Sampling

4.5. Antioxidant Properties Analyses

4.6. Untargeted Metabolome Analysis of Broiler Ileum

4.6.1. Extraction of Metabolites

4.6.2. Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrum Parameters

4.6.3. Data Extraction and Processing

4.7. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sittiya, J.; Yamauchi, K.; Takata, K. Effect of replacing corn with whole-grain paddy rice and brown rice in broiler diets on growth performance and intestinal morphology. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 100, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikrishna A, Dutta S, Subramanian V, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C. Ageing of rice: A review. Journal of Cereal Science. 2018;81:161–70.

- Zhang, M.; Liu, K. Lipid and Protein Oxidation of Brown Rice and Selenium-Rich Brown Rice during Storage. Foods 2022, 11, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, S.; Wang, Q.; Shang, B.; Liu, J.; Xing, X.; Hong, Y.; Liu, H.; Duan, X.; Sun, H. Lipidomics and volatilomics reveal the changes in lipids and their volatile oxidative degradation products of brown rice during accelerated aging. Food Chem. 2023, 421, 136157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou K, Luo Z, Huang W, Liu Z, Miao X, Tao S, et al. Biological Roles of Lipids in Rice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences [Internet]. 2024;25. Available from: https://www.mdpi. 1422.

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species signalling in plant stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, B.J.; Kellner, T.A.; Shurson, G.C. Characteristics of lipids and their feeding value in swine diets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, X.; Liang, Y.; Wu, W. Potential implications of oxidative modification on dietary protein nutritional value: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 22, 714–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Kerr, B.J.; Curry, S.M.; Chen, C. Identification of C9-C11 unsaturated aldehydes as prediction markers of growth and feed intake for non-ruminant animals fed oxidized soybean oil. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, B.J.; Lindblom, S.C.; Zhao, J.; Faris, R.J. Influence of feeding thermally peroxidized lipids on growth performance, lipid digestibility, and oxidative status in nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Frame, C.; Johnson, E.; Kilburn, L.; Huff-Lonergan, E.; Kerr, B.J.; Serao, M.R. Impact of dietary oxidized protein on oxidative status and performance in growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, K. Lipid and Protein Oxidation of Brown Rice and Selenium-Rich Brown Rice during Storage. Foods 2022, 11, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.T.; Liu, K.; Han, S.; Jatoi, M.A. The Effects of Thermal Treatment on Lipid Oxidation, Protein Changes, and Storage Stabilization of Rice Bran. Foods 2022, 11, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, R.B.; Lincoln, L.; Momen, S.; Minkoff, B.B.; Sussman, M.R.; Girard, A.L. Role of protein and lipid oxidation in hardening of high-protein bars during storage. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e17657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Al Mahmud, J.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Bi, J.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, X.; Wang, P.; Shu, Z. Quality changes in Chinese high-quality indica rice under different storage temperatures with varying initial moisture contents. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1334809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Arif, Y.; Miszczuk, E.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Specific Roles of Lipoxygenases in Development and Responses to Stress in Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Lin, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fang, G. Nutritional Changes and Early Warning of Moldy Rice under Different Relative Humidity and Storage Temperature. Foods 2022, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Duan, X.; Shang, B.; Hong, Y.; Sun, H. Analysis of lipidomics profile of rice and changes during storage by UPLC-Q-extractive orbitrap mass spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirgozliev VR, Birch,C.L., Rose,S.P., Kettlewell,P.S., and Bedford MR. Chemical composition and the nutritive quality of different wheat cultivars for broiler chickens. British Poultry Science. 2003;44:464–75.

- Pirgozliev, V.; Rose, S.; Kettlewell, P. Effect of ambient storage of wheat samples on their nutritive value for chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2006, 47, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavárez, M.; Boler, D.; Bess, K.; Zhao, J.; Yan, F.; Dilger, A.; McKeith, F.; Killefer, J. Effect of antioxidant inclusion and oil quality on broiler performance, meat quality, and lipid oxidation. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Yuan, J.; Guo, Y.; Chiba, L.I. Effect of storage time on the characteristics of corn and efficiency of its utilization in broiler chickens. 3. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, H.A.; Shivazad, M.; Mirzapour Rezaei, S.S.; Karimi orshizi, M.A. Effect of synbiotic supplementation and dietary fat sources on broiler performance, serum lipids, muscle fatty acid profile and meat quality. Br. Poult. Sci. 2016, 57, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hong, T.; Zhao, Z.; Gu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Han, J. Fatty Acid Profiles and Nutritional Evaluation of Fresh Sweet-Waxy Corn from Three Regions of China. Foods 2022, 11, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munarko, H.; Sitanggang, A.B.; Kusnandar, F.; Budijanto, S. Phytochemical, fatty acid and proximal composition of six selected Indonesian brown rice varieties. CyTA - J. Food 2020, 18, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortinas, L.; Villaverde, C.; Galobart, J.; Baucells, M.D.; Codony, R.; Barroeta, A.C.; Baucells, M.D. Fatty Acid Content in Chicken Thigh and Breast as Affected by Dietary Polyunsaturation Level. Poult. Sci. 2004, 83, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.P.; Leskovec, J.; Levart, A.; Pirman, T.; Salobir, J.; Rezar, V. Comparison of High n-3 PUFA Levels and Cyclic Heat Stress Effects on Carcass Characteristics, Meat Quality, and Oxidative Stability of Breast Meat of Broilers Fed Low- and High-Antioxidant Diets. Animals 2024, 14, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NR, Abdulla, TC, Loh, H, Akit, et al. Fatty Acid Profile, Cholesterol and Oxidative Status in Broiler Chicken Breast Muscle Fed Different Dietary Oil Sources and Calcium Levels. South African Journal of Animal Science. 2015.

- Prates, J.A.M. Nutritional Value and Health Implications of Meat from Monogastric Animals Exposed to Heat Stress. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbruslais, A.; Wealleans, A.L. Oxidation in Poultry Feed: Impact on the Bird and the Efficacy of Dietary Antioxidant Mitigation Strategies. Poultry 2022, 1, 246–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu Y, Zhang K, Bai S, Wang JP, Zeng Q, Ding X. Effects of vitamin E supplementation on performance, serum biochemical parameters and fatty acid composition of egg yolk in laying hens fed a diet containing ageing corn. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2019;103:135–45.

- Raes, K.; De Smet, S.; Demeyer, D.; Huyghebaert, G.; Nollet, L.; Arnouts, S. The Deposition of Conjugated Linoleic Acids in Eggs of Laying Hens Fed Diets Varying in Fat Level and Fatty Acid Profile. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, B.J.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, S.K. Effects of Feeding Rancid Rice Bran on Growth Performance and Chicken Meat Quality in Broiler Chicks. Asian-Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 15, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Osowiecka, M.; Ott, C.; Tziraki, V.; Meusburger, L.; Blaßnig, C.; Krivda, D.; Pjevac, P.; Séneca, J.; Strauss, M.; et al. Dietary oxidized lipids in redox biology: Oxidized olive oil disrupts lipid metabolism and induces intestinal and hepatic inflammation in C57BL/6J mice. Redox Biol. 2025, 81, 103575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.-J.; Won, Y.-S.; Kim, E.-K.; Park, S.-I.; Lee, S.J. Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: a review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Zaki, E.F.; Salama, A.A.; Badri, F.B.; Thabet, H.A. Assessing different oil sources efficacy in reducing environmental heat-stress effects via improving performance, digestive enzymes, antioxidant status, and meat quality. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, B.; Shi, J.; Liu, K.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, A. Evaluation of the Available Energy Value and Amino Acid Digestibility of Brown Rice Stored for 6 Years and Its Application in Pig Diets. Animals 2023, 13, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Yang, X. Dietary folic acid addition reduces abdominal fat deposition mediated by alterations in gut microbiota and SCFA production in broilers. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 12, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winarti C, Widaningrum, Widayanti SM, Setyawan N, Qanytah, Juniawati, et al. Nutrient Composition of Indonesian Specialty Cereals: Rice, Corn, and Sorghum as Alternatives to Combat Malnutrition. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2023;28:471–82.

- Boronovskiy, S.E.; Kopylova, V.S.; Nartsissov, Y.R. Metabolism and Receptor Mechanisms of Niacin Action. Cell Tissue Biol. 2024, 18, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, R.; Sawan, S.A.; Orrú, M.; Tinlsey, G.M.; Purpura, M.; Wells, S.D.; Liao, K.; Godavarthi, A.; Abreu-Villaça, Y. 1-Methylxanthine enhances memory and neurotransmitter levels. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0313486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, H.-S.; Sponder, G.; Pieper, R.; Aschenbach, J.R.; Deiner, C. GABA selectively increases mucin-1 expression in isolated pig jejunum. Genes Nutr. 2015, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai J, Rimal B, Jiang C, Chiang JYL, Patterson AD. Bile acid metabolism and signaling, the microbiota, and metabolic disease. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2022;237:108238.

- Wang, W.; Zhao, J.; Gui, W.; Sun, D.; Dai, H.; Xiao, L.; Chu, H.; Du, F.; Zhu, Q.; Schnabl, B.; et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid inhibits intestinal inflammation and barrier disruption in mice with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 175, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.-H.; Kim, M.; Yun, C.-H. Regulation of Gastrointestinal Immunity by Metabolites. Nutrients 2021, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzikowska, U.; Rinaldi, A.O.; Çelebi, Z.C.; Karaguzel, D.; Wojcik, M.; Cypryk, K.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A.; Sokolowska, M. The Influence of Dietary Fatty Acids on Immune Responses. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Mei, X.; He, Z.; Xie, X.; Yang, Y.; Mei, C.; Xue, D.; Hu, T.; Shu, M.; Zhong, W. Nicotine metabolism pathway in bacteria: mechanism, modification, and application. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, T.; Dai, W.; Zhang, C. NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase mediates resistance to neonicotinoid insecticides in Bradysia odoriphaga. . 2025, 211, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | BR6 | BR1 | P-value |

| Fatty acid value (mg KOH/100 g) | 27.83 ± 2.11a | 17.44 ± 1.05b | < 0.01 |

| MDA (nmol/mg) | 6.24 ± 0.54a | 3.67 ± 0.30b | < 0.01 |

| Carbonylated protein (nmol/mg) | 3.25 ± 0.32a | 1.60 ± 0.05b | < 0.01 |

| SOD (U/mg) | 6.48 ± 0.93 | 6.52 ± 0.52 | 0.97 |

| GSH-PX (U/mg) | 41.80 ± 5.45b | 68.13 ± 5.87a | < 0.01 |

| GSH (μmol/mg) | 1.52 ± 0.06b | 2.18 ± 0.18a | <0.01 |

| CAT (U/mg) | 7.44 ± 0.86 | 8.40 ± 0.67 | 0.40 |

| LPS (U/mg) | 2.66 ± 0.33 | 1.86 ± 0.36 | 0.13 |

| APX (U/mg) | 0.94 ± 0.10 | 1.25 ± 0.15 | 0.11 |

| Items | BR6 | BR1 | P-value |

| Myristic acid (C14: 0) | 0.55 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 0.75 |

| Palmitic acid (C16: 0) | 25.40 ± 0.07 | 25.58 ± 0.17 | 0.27 |

| Stearic acid (C18: 0) | 2.13 ± 0.06a | 1.86 ± 0.02b | < 0.01 |

| Oleic acid (C18: 1n-9c) | 33.98 ± 0.18a | 31.74 ± 0.44b | < 0.01 |

| Linoleic acid (C18: 2n-6c) | 33.88 ± 0.27b | 36.01 ± 0.25a | < 0.01 |

| Alpha-linolenic acid (C18: 3n-3) | 1.07 ± 0.02b | 1.46 ± 0.03a | < 0.01 |

| Icosanoic acid (C20: 0) | 0.64 ± 0.02a | 0.56 ± 0.00b | < 0.01 |

| Eicosenoic acid (C20: 1) | 0.55 ± 0.01a | 0.50 ± 0.01b | < 0.01 |

| Docosanoic acid (C22: 0) | 0.33 ± 0.01a | 0.30 ± 0.00b | 0.03 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (C22: 6n-3) | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.79 |

| Tricosanoic acid (C23: 0) | 0.30 ± 0.01b | 0.36 ± 0.01a | 0.04 |

| Tetracosanoic acid acid (C24: 0) | 0.84 ± 0.04a | 0.72 ± 0.01b | 0.03 |

| Total (g/100g) | 2.91± 0.16 | 2.69± 0.03 | 0.23 |

| SFA | 30.16 ± 0.18 | 29.91 ± 0.19 | 0.38 |

| MUFA | 34.53 ± 0.19a | 32.24 ± 0.45b | < 0.01 |

| PUFA | 35.32 ± 0.28b | 37.85 ± 0.29a | < 0.01 |

| UFA | 69.84 ± 0.18 | 70.09 ± 0.19 | 0.38 |

| SFA/UFA | 0.43 ± 0.00 | 0.43 ± 0.00 | 0.38 |

| PUFA/SFA | 1.17 ± 0.02b | 1.27 ± 0.01a | < 0.01 |

| Items | BR6 | BR1 | P-value | |

| Growth performance | ||||

| Feed intake, kg | ||||

| Wk 0 to 3 | 36.24 ± 0.42 | 36.32 ± 0.85 | 35.22 ± 0.66 | 0.44 |

| Wk 4 to 6 | 98.45 ± 3.33 | 93.70 ± 4.64 | 94.77 ± 3.97 | 0.69 |

| Wk 0 to 6 | 67.36 ± 1.78 | 64.95 ± 2.08 | 64.95 ± 2.26 | 0.64 |

| Body weight gain, kg | ||||

| Wk 0 to 3 | 27.60 ± 0.29 | 26.65 ± 0.57 | 26.72 ± 0.47 | 0.29 |

| Wk 4 to 6 | 63.65 ± 1.31 | 62.51 ± 0.92 | 64.85 ± 0.65 | 0.28 |

| Wk 0 to 6 | 45.64 ± 0.74 | 44.58 ± 0.42 | 45.79 ± 0.54 | 0.30 |

| FCR | ||||

| Wk 0 to 3 | 1.31 ± 0.01b | 1.36 ± 0.01a | 1.32 ± 0.01b | 0.03 |

| Wk 4 to 6 | 1.55 ± 0.05 | 1.50 ± 0.06 | 1.46 ± 0.06 | 0.56 |

| Wk 0 to 6 | 1.48 ± 0.03 | 1.47 ± 0.04 | 1.42 ± 0.04 | 0.58 |

| Meat quality | ||||

| pH | 5.63 ± 0.02 | 5.58 ± 0.02 | 5.62 ± 0.01 | 0.13 |

| Drop loss, % | 5.56 ± 0.28b | 7.00 ± 0.25a | 5.93 ± 0.36b | < 0.01 |

| Cooking percentage, % | 63.48 ± 0.96 | 60.53 ± 0.92 | 61.58 ± 0.55 | 0.06 |

| Items | Corn | BR6 | BR1 | P-value |

| Myristic acid (C14: 0) | 0.55 ± 0.02ab | 0.61 ± 0.06a | 0.49 ± 0.02b | 0.09 |

| Palmitic acid (C16: 0) | 22.91 ± 0.39b | 24.48 ± 0.23a | 24.39 ± 0.18a | < 0.01 |

| Palmitoleic acid (C16: 1) | 1.29 ± 0.09b | 2.54 ± 0.14a | 2.79 ± 0.08a | < 0.01 |

| Stearic acid (C18: 0) | 14.37 ± 0.37a | 12.75 ± 0.36b | 11.90 ± 0.19b | < 0.01 |

| Oleic acid (C18: 1n-9c) | 20.59 ± 0.54b | 26.98 ± 1.13a | 28.49 ± 0.31a | < 0.01 |

| Linoleic acid (C18: 2n-6c) | 23.87 ± 0.60a | 19.56 ± 0.37b | 20.03 ± 0.34b | < 0.01 |

| Alpha-linolenic acid (C18: 3n-3) | 1.05 ± 0.07 | 0.96 ± 0.06 | 1.15 ± 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Eicosenoic acid (C20: 1) | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.13 |

| Eicosandienoic acid (C20: 2) | 1.32 ± 0.10a | 0.79 ± 0.06b | 0.71 ± 0.04b | < 0.01 |

| Sciadonic acid (C20: 3n-6) | 1.28 ± 0.09 | 1.34 ± 0.13 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 0.17 |

| Docosadienoic acid (C20: 4n-6) | 8.52 ± 0.51a | 6.02 ± 0.48b | 5.36 ± 0.16b | < 0.01 |

| Erucic Acid (C22: 1n-9) | 2.51 ± 0.28 | 2.48 ± 0.32 | 0.33 ± 0.21 | 0.89 |

| Nervonic acid (C24: 1) | 0.55 ± 0.02a | 0.54 ± 0.05a | 0.43 ± 0.02b | 0.04 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (C22: 6n-3) | 0.67 ± 0.05a | 0.47 ± 0.04b | 0.48 ± 0.02b | < 0.01 |

| Total (mg/g) | 0.61± 0.02b | 0.84 ± 0.07a | 0.92 ± 0.05a | < 0.01 |

| SFA | 37.82 ± 0.63 | 37.5 ± 0.36 | 36.78 ± 0.27 | 0.18 |

| MUFA | 25.48 ± 0.62b | 33.01 ± 0.92a | 34.33 ± 0.33a | < 0.01 |

| PUFA | 36.70 ± 0.27a | 29.1 ± 0.68b | 28.83 ± 0.50b | < 0.01 |

| UFA | 62.18 ± 0.63 | 62.15 ± 0.36 | 63.22 ± 0.7 | 0.18 |

| SFA/UFA | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.61 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 0.18 |

| PUFA/SFA | 0.97 ± 0.02a | 0.77 ± 0.02b | 0.78 ± 0.02b | < 0.01 |

| MUFA/PUFA | 0.69 ± 0.02b | 1.14 ± 0.06a | 1.20 ± 0.03a | < 0.01 |

| EFA | 24.92 ± 0.66a | 20.52 ± 0.38b | 21.19 ± 0.37b | < 0.01 |

| Items | Corn | BR6 | BR1 | P-value |

| MDA | 0.91 ± 0.02a | 0.62 ± 0.01b | 0.51 ± 0.01c | < 0.01 |

| SOD (U/mg) | 10.52 ± 0.35b | 11.73 ± 0.42a | 12.42 ± 0.27a | < 0.01 |

| TAOC (U/mg) | 1.99 ± 0.02b | 2.72 ± 0.08a | 2.89 ± 0.10a | < 0.01 |

| GSH-PX (U/mg) | 266.12 ± 8.32b | 305.07 ± 13.29a | 308.06 ± 9.73a | 0.02 |

| CAT (U/mg) | 9.64 ± 0.47b | 13.04 ± 0.29a | 13.81 ± 0.29a | < 0.01 |

| α-AMY (U/mg) | 1.11 ± 0.03a | 0.84 ± 0.02b | 1.12 ± 0.04a | < 0.01 |

| Trypsin (U/mg) | 39.01 ± 1.80a | 27.40 ± 1.54b | 42.96 ± 1.21a | < 0.01 |

| Chymotrypsin (U/mg) | 70.00 ± 2.71a | 55.37 ± 0.94b | 74.65 ± 4.16a | < 0.01 |

| LPS (U/mg) | 50.94 ± 0.94b | 42.69 ± 1.57c | 56.30 ± 2.34a | < 0.01 |

| Items | 1 to 21 days of age | 22 to 42 days of age | ||||

| Corn | BR6 | BR1 | Corn | BR6 | BR1 | |

| Ingredients | ||||||

| Corn | 55.88 | / | / | 60.74 | / | / |

| Soybean meal | 34.76 | 35.04 | 35.90 | 27.48 | 27.90 | 27.90 |

| BR6 | 0.00 | 56.97 | / | 0.00 | 62.51 | / |

| BR1 | 0.00 | / | 56.68 | 0.00 | / | 62.76 |

| Corn gluten meal | 3.00 | 2.22 | 1.50 | 4.42 | 4.12 | 3.83 |

| Soybean oil | 3.28 | 1.90 | 2.10 | 3.68 | 1.98 | 2.00 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.78 | 1.68 | 1.68 | 1.48 | 1.38 | 1.38 |

| Limestone | 1.26 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.24 | 1.30 | 1.32 |

| NaCl | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Vitamin premixa | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Mineral premixb | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Choline chloride (50%) | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Met | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Lys-HCl (98%) | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Thr | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Nutrients levels4 | ||||||

| Dry matter | 89.05 | 88.91 | 89.67 | 88.70 | 89.10 | 88.63 |

| Crude protein | 21.59 | 21.40 | 21.46 | 20.16 | 20.07 | 19.92 |

| Calcium | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| Total phosphorus | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| Metabolizable energy, MJ/kgc | 12.48 | 12.48 | 12.48 | 12.89 | 12.89 | 12.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).