1. Introduction

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into histopathology has revolutionized cancer diagnostics, enabling the extraction of intricate morphological and spatial features from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained whole slide images (WSIs) [

1]. AI-driven approaches have demonstrated remarkable potential in predicting molecular phenotypes and genomic alterations from histopathological images. Various AI models have been successfully applied to classify cancer subtypes, predict microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and infer tumor mutational burden (TMB) from WSIs [

2,

3]. These advancements underscore the transformative role of AI in bridging the gap between histopathology and molecular diagnostics.

Recent studies have highlighted the ability of AI to detect subtle visual markers in H&E-stained WSIs, which correlate with underlying genomic alterations and molecular phenotypes [

4,

5]. This capability is particularly relevant for homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) prediction, as HRD arises from complex genomic and molecular mechanisms that manifest in cellular morphology. By training AI models on H&E stained WSIs, researchers have achieved high-precision predictions of molecular status, offering a non-invasive and cost-effective alternative to traditional methods [

6]. Moreover, AI-driven digital pathology enables the integration of multi-omics data, enhancing the accuracy of predictive models and supporting personalized therapeutic strategies [

7].

HRD has emerged as a critical biomarker in oncology, guiding therapeutic decisions for Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and platinum-based treatments. HRD reflects genome-wide scarring and impaired DNA repair mechanisms, often resulting in chromosomal instability. Traditional methods for HRD detection, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), are highly effective but limited by their cost, and lengthy turnaround times. These limitations have spurred the exploration of alternative approaches, particularly those leveraging advancements in digital pathology and AI.

It is known that HRD is caused by BRCA1/2 mutations and yet not all patients with mutations in BRCA1/2 respond to PARP inhibitors. The differences in response to PARP inhibitor treatment could also result from the development of resistance. In addition, PARP inhibitor resistance could result from restoration of homologous recombination (HR) repair due to secondary mutations in BRCA1/2, and depletion of HR compensatory repair pathways such as the non-homologous end joining pathway.

Increasingly NGS large somatic panels on tumor DNA are being used to personalize the treatments, however these tests have their limitations. Example, the Myriad Genetics test uses sequencing to find BRCA mutations and produces a ‘genomic instability’ score that is related to DNA damage. However, the threshold at which a score is said to identify HRD is controversial. In addition, the current tests also have false positives with no mutations detections (NMDs), leading to non-reliable predictors with benefit from PARP inhibitors. It also detects pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 within the same assay.

Using a ResNet-50-based model, we aim to address the limitations of traditional HRD detection methods and explore the feasibility of AI-driven digital pathology as a rapid screening tool. The approach reported here utilizes AI to extract morphological and architectural features associated with HRD, offering a scalable and efficient solution for patient stratification and therapeutic decision-making in precision oncology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Preparation

A total of 514, including 395 H&E-stained WSIs were collected from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The dataset consisted of 315 breast cancer slides and 80 ovarian cancer slides. Ground truth labels for HRD status—classified as HRD-positive or HRD-negative—were retrieved from TCGA. The model was internally validated with a private dataset of 119 ovarian cancer samples with known BRCA1/2 status, other relevant homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene mutations, or HRD status.

2.2. HRD Scores and Associated Genomic Markers

HRD scores were calculated using scarHRD, as described by Sztupinszki et al. [

8]. Clinically, an HRD score of ≥42 is commonly used to guide treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy or PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer, as established by Telli et al. [

9,

10]. Additionally, a threshold of ≥63 has been proposed in certain treatment contexts, as reported by Takaya et al. [

11]. The HRD score threshold was centered at 50, reflecting the median HRD score for ovarian cancer [

12]. Samples were classified as HRD if they had an HRD score ≥50 or harbored BRCA1/2 mutations or alterations in other relevant HRR genes. Conversely, samples with an HRD score <50 and no detected mutations in other relevant HRR genes were considered homologous recombination proficient, corresponding to the upper and lower quartiles, respectively. Pathogenicity of mutations in BRCA1/2 and 24 additional HRD-related genes were assessed by cross-referencing variants across multiple genomic databases, as previously described by Abkevich et al. [

13].

2.3. Histopathological Feature Extraction

Histopathological features were extracted from H&E-stained slides to capture the morphological and structural characteristics of the tumor regions. These features encompassed aspects such as cellular architecture, nuclear morphology, and overall tissue organization, which are essential for distinguishing between HRD-positive and HRD-negative cases.

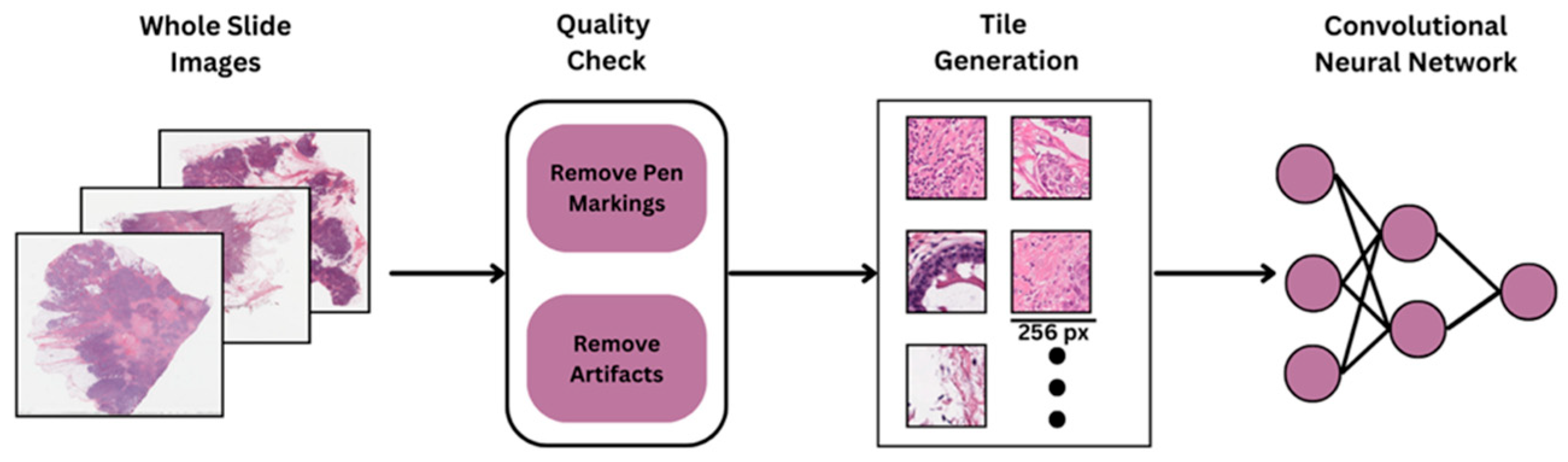

2.4. Image Preprocessing and Tile Generation

To facilitate deep learning-based analysis, all H&E-stained WSIs underwent a standardized preprocessing and tiling workflow. Due to the high resolution of WSIs, each slide was divided into smaller, manageable regions for model training. Initially, each WSI was visually inspected to ensure quality control, removing slides with scanning artifacts, pen marks, or incomplete tissue sections. Following quality control, tissue segmentation was performed using color thresholding and morphological operations to generate tissue masks, effectively distinguishing tissue regions from background areas using HistoQC. (

Figure 1). Only regions with sufficient tissue coverage (e.g., >90% tissue area) were retained for further processing to avoid including empty or irrelevant background regions.

The WSIs were then divided into non-overlapping tiles of 256 × 256 pixels at a 40× magnification level (approximately 0.25 μm/pixel). This high magnification setting was selected to capture critical cellular and architectural features relevant for downstream deep learning tasks. The tiling strategy ensured comprehensive sampling of each slide, resulting in a diverse and representative collection of image patches reflecting both tumor and stromal regions.

To reduce the variability in H&E staining across samples originating from multiple centers in TCGA, stain normalization was applied to all tiles. The normalization was performed using a structure-preserving method to standardize color profiles while maintaining morphological integrity. This step was crucial for mitigating stain-related biases and improving the generalization capability of the deep learning model across heterogeneous datasets. The final set of pre-processed tiles was used as input to the deep learning pipeline, enabling robust feature extraction and classification at the patch level.

2.5. Dataset Splitting

The dataset was split into training and validation subsets to ensure robust model evaluation. Specifically: 80% of the data was allocated for training the AI model. 20% of the data was reserved for validation to assess the model’s performance and generalizability.

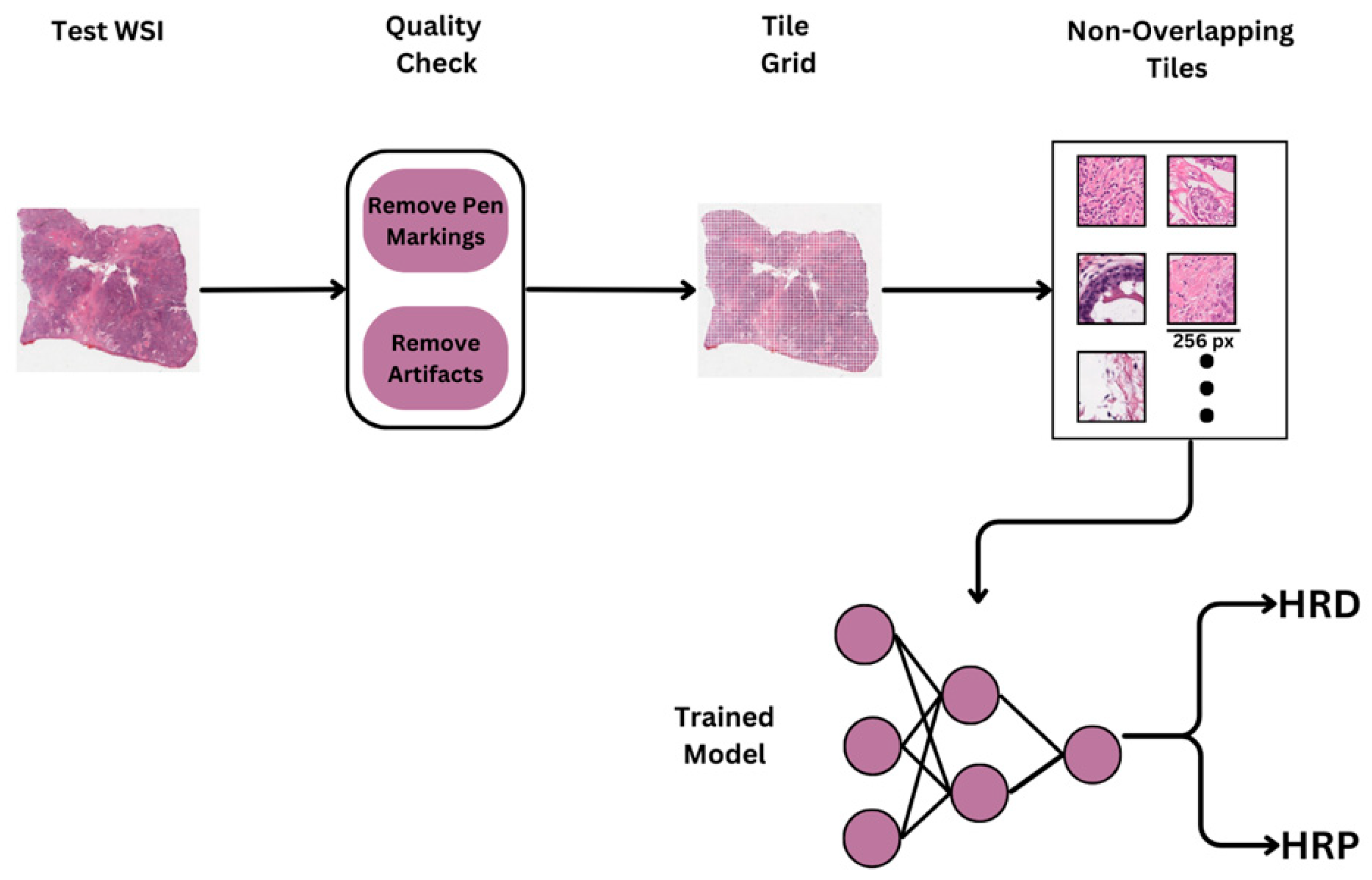

2.6. OncoPredikt Model Architechture

In this study, we implemented a tumor detection pipeline to identify tumor regions within WSIs, followed by classification using the ResNet-50 architecture, a widely recognized deep learning model for image analysis tasks (

Figure 2). The tumor detection pipeline included an initial preprocessing stage to eliminate artifacts, after which feature extraction was performed using a pretrained Hibou model fine-tuned on tiles from the BCSS dataset (

https://bcsegmentation.grand-challenge.org/). The tumor detection model carried out segmentation by accurately delineating tumor regions within H&E-stained slides. Subsequently, these segmented tumor regions were utilized for HRD status prediction.

2.7. Model Training

The objective of the study was to develop HRD classification models for both breast and ovarian cancer samples. A common custom architecture was designed by leveraging the pre-trained weights of the ResNet50 model. Transfer learning was applied to fine-tune the model on image tiles categorized under HRD and HRP (homologous recombination proficient) classes. For optimization, binary cross-entropy was used as the loss function, and the Adam optimizer was employed to update model weights efficiently. The training process involved multiple epochs to achieve a better accuracy with reduced loss. As mentioned earlier, 80-20 split is adapted for training and validating both the models.

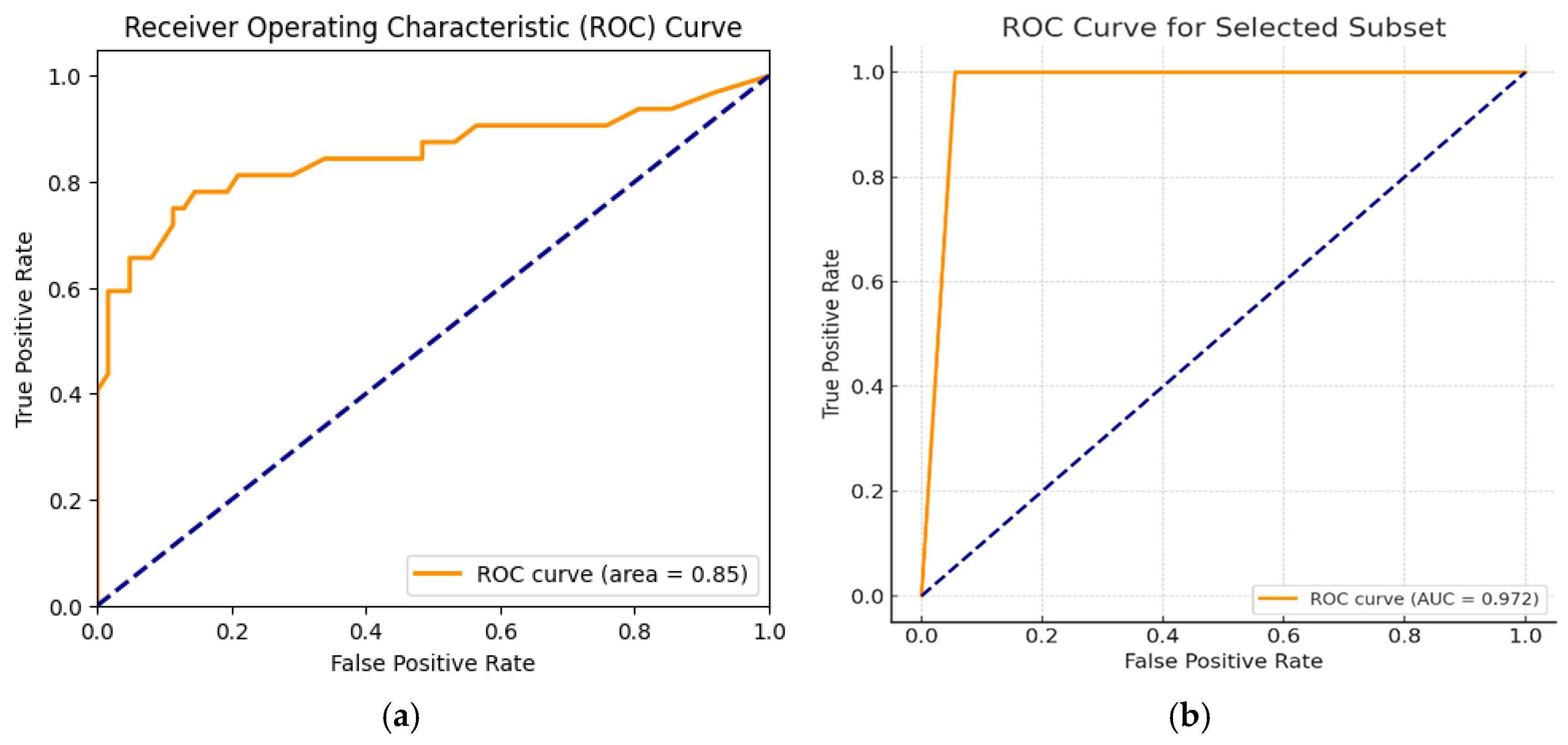

2.8. OncoPredikt Model Validation

The trained models for both breast and ovarian samples were validated on the reserved 20% of the validation set. Performance metrics such as Sensitivity, Specificity and (Receiver operating characteristic) ROC/(Area under curve) AUC were calculated to evaluate the model’s ability to predict HRD status. The validation results were compared against the NGS ground truth to assess the model’s reliability and generalizability.

3. Results

The OncoPredikt model was trained and evaluated on a total of 514 H&E-stained whole slide images (WSIs) of breast and ovarian cancer. A total of 395 WSIs were obtained from TCGA, consisting of 315 breast cancer and 80 ovarian cancer slides. Ground truth labels for HRD status—categorized as HRD-positive or HRD-negative—were calculated using scarHRD, as described by Sztupinszki et al. [

8]. The model was further validated on an independent private dataset of 119 ovarian cancer samples with known BRCA1/2 status, HRR gene mutations, or HRD status.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the successful development and validation of an AI-based pipeline for predicting HRD status directly from H&E-stained WSIs across two major cancer types: ovarian and breast cancer. Leveraging a ResNet-50 backbone, our models exhibited promising predictive potential, particularly when trained on tumor-segmented and stain-normalized regions. The ovarian cancer-specific model achieved a true positive rate of approximately 97%, highlighting its high sensitivity for HRD prediction in ovarian cancer. Similarly, the breast cancer model demonstrated moderate cross-cancer performance (AUC-ROC = 0.85), with stain normalization significantly enhancing its predictive accuracy. These results align with recent studies demonstrating the ability of deep learning (DL) models to extract subtle morphological features associated with molecular phenotypes and genomic alterations [

4,

6] and studies indicating that machine learning-based cancer classification models often face challenges in achieving high specificity, particularly in heterogeneous cancers such as breast and ovarian cancer [

14]. The superior performance may be attributed to more distinct molecular profiles, which exhibit higher genomic heterogeneity [

15,

16]. Future work should focus on improving specificity in breast and ovarian cancer detection, potentially by integrating multi-omics data and advanced DL approaches [

17,

18].

However, the models achieved modest AUC-ROC values for pancreatic and prostate cancer (0.48 and 0.51 at HRD cutoffs of 42 and 50, respectively), indicating challenges posed by tumor heterogeneity across different cancer types (data not shown here). This variability highlights the complexity of generalizing HRD prediction models across diverse histological and molecular landscapes, a challenge also noted in previous studies [

2,

19]. Despite these limitations, the model’s high specificity in reducing false positives is a significant advantage, as it minimizes unnecessary HRD testing for HRD-negative patients, thereby conserving resources and accelerating clinical decision-making.

The integration of stain normalization and tumor segmentation techniques proved critical in enhancing model performance. Stain normalization addressed variability in staining protocols and scanner differences, while tumor segmentation ensured that predictions were based on biologically relevant tissue regions. These preprocessing steps not only improved model accuracy but also underscored the importance of addressing technical and biological variability in digital pathology workflows, as highlighted in prior research [

1,

20].

Our findings contribute evidence supporting the use of AI-driven digital pathology for molecular biomarker prediction. We approach bridges the gap between histopathology and molecular diagnostics, offering a cost-effective and efficient solution for HRD prediction. This aligns with recent advancements in the field, which have demonstrated the potential of AI to integrate multi-omics data and enhance predictive accuracy [

3,

21].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential of AI-powered histopathological image analysis as a rapid, non-invasive screening tool for HRD prediction. The strong performance of the ovarian and breast cancer-specific models, coupled with the model’s high specificity, underscores its clinical utility in optimizing patient stratification for HRD-targeted therapies such as PARP inhibitors and platinum-based treatments. While challenges related to tumor heterogeneity remain, our findings provide a foundation for further refinement and expansion of this framework. Future work necessitates validating the model on larger and more diverse pan-cancer datasets, as well as exploring its applicability to other clinically actionable molecular layers including transcriptome and clinical features. By advancing the role of AI in precision oncology, there is immense potential to transform cancer diagnostics and therapeutic decision-making, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.U., K.B. and G.S.; methodology, A.U. and S.P.M.; software, S.P.M.; formal analysis, A.U.; data curation, S.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| HRD |

Homologous recombination deficiency |

| TAT |

Turn-around time |

| H&E |

Hematoxylin and eosin |

| TCGA |

The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| HRR |

Homologous recombination repair |

| AUC |

Area under curve |

| PPV |

Positive predictive value |

| NPV |

Negative predictive value |

| WSI |

Whole slide image |

| MSI |

Microsatellite instability |

| TMB |

Tumor mutational burden |

| PARP |

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| NMD |

No mutations detection |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

| HRP |

Homologous recombination proficient |

| QC |

Quality control |

| DL |

Deep learning |

References

- Janowczyk, A.; Zuo, R.; Gilmore, H.; Feldman, M.; Madabhushi, A. HistoQC: An open-source quality control tool for digital pathology slides. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2019, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Nimir, M.; Snead, D.; Taylor, G.S.; Rajpoot, N. Role of AI and digital pathology for colorectal immuno-oncology. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Lv, H.; Zhao, S.; Lin, C.J.; Su, G.H.; Shao, Z.M. Prediction of clinicopathological features, multi-omics events and prognosis based on digital pathology and deep learning in HR+/HER2− breast cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2023, 15, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Yang, W.; Han, X.; Liu, Y. Automatic diagnosis and grading of prostate cancer with weakly supervised learning on whole slide images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 152, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafi, G.; PM, S.; Ulle, A.; Srinivasan, K.; Vasudevan, A.; Jadhav, V.; Joshi, D.S.; Raut, N.V.; Khandare, J.; Uttarwar, M.; Bloom, K.J. AI-enabled identification prediction of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) from histopathology images. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Dinstag, G.; Hermida, L.C.; Ben-Zvi, D.S.; Elis, E.; Caley, K.; Sammut, S.J.; Sinha, S.; Sinha, N.; Dampier, C.H.; et al. Prediction of cancer treatment response from histopathology images through imputed transcriptomics. Res. Sq. [Preprint] 2023, rs.3:rs-3193270, Update in: Nat. Cancer. 2024, 5, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zeng, H.; Xiang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ma, X. Histopathological images and multi-omics integration predict molecular characteristics and survival in lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 720110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sztupinszki, Z.; Diossy, M.; Krzystanek, M.; Reiniger, L.; Csabai, I.; Favero, F.; Birkbak, N.J.; Eklund, A.C.; Syed, A.; Szallasi, Z. Migrating the SNP array-based homologous recombination deficiency measures to next generation sequencing data of breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2018, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telli, M.L. Triple-negative breast cancer. In Molecular Pathology of Breast Cancer; Badve, S., Gökmen-Polar, Y., Eds.; Springer, 2016; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Telli, M.L.; Stover, D.G.; Loi, S.; Aparicio, S.; Carey, L.A.; Domchek, S.M.; Newman, L.; Sledge, G.W.; Winer, E.P. Homologous recombination deficiency and host anti-tumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 171, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaya, H.; Nakai, H.; Takamatsu, S.; Mandai, M.; Matsumura, N. Homologous recombination deficiency status-based classification of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timms, K.M.; Abkevich, V.; Hughes, E.; Neff, C.; Reid, J.; Morris, B.; Kalva, S.; Potter, J.; Tran, T.V.; Chen, J.; Iliev, D. Association of BRCA1/2 defects with genomic scores predictive of DNA damage repair deficiency among breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abkevich, V.; Timms, K.M.; Hennessy, B.T.; Potter, J.; Carey, M.S.; Meyer, L.A.; Smith-McCune, K.; Broaddus, R.; Lu, K.H.; Chen, J.; Tran, T.V. Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict homologous recombination repair defects in epithelial ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1776–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, T.P.; Exarchos, K.P.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Fotiadis, D.I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. (CSBJ) 2015, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Ledesma, E.; Verhaak, R.G.; Treviño, V. Identification of a multi-cancer gene expression biomarker for cancer clinical outcomes using a network-based algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Rueda, H.; Martínez-Ledesma, E.; Martínez-Torteya, A.; Palacios-Corona, R.; Trevino, V. Integration and comparison of different genomic data for outcome prediction in cancer. BioData Min. 2015, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Bi, M.; Guo, H.; Li, M. Multi-omics approaches for biomarker discovery in early ovarian cancer diagnosis. EBioMedicine 2022, 79, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wekesa, J.S.; Kimwele, M. A review of multi-omics data integration through deep learning approaches for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1199087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shmatko, A.; Ghaffari Laleh, N.; Gerstung, M.; Kather, J.N. Artificial intelligence in histopathology: Enhancing cancer research and clinical oncology. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahadane, A.; Peng, T.; Sethi, A.; Albarqouni, S.; Wang, L.; Baust, M.; Steiger, K.; Schlitter, A.M.; Esposito, I.; Navab, N. Structure-preserving color normalization and sparse stain separation for histological images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging (T-MI) 2016, 35, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, M.; Alexanderani, M.K.; Valencia, I.; Loda, M.; Marchionni, L. Applications of digital pathology in cancer: A comprehensive review. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2024, 8, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).