1. Introduction

Carbon storage is a crucial component of the global carbon cycle and vital for mitigating global warming [

1]. Against the backdrop of global climate change and rapid economic development, reducing carbon emissions alone is insufficient to address climate risks [

2]. Enhancing the carbon storage capacity of ecosystems is imperative. Soil carbon pools in terrestrial ecosystems account for over 80% of global terrestrial carbon cycling [

3]. Marine ecosystems also possess extremely high carbon fixation efficiency, with a per-unit carbon storage efficiency 15 times that of terrestrial systems [

3]. The coastal zone serves as a link between land and sea, simultaneously encompassing both marine and terrestrial carbon pools [

4]. It includes important marine ecosystems such as mangroves, tidal flats, and salt marshes, as well as terrestrial carbon reservoirs like forests and soils, all of which possess exceptional carbon storage capacity [

5]. However, coastal zones experience significant population concentration [

6], resulting in higher human disturbance and increased ecosystem vulnerability. Bays are the most geographically advantageous areas of the coastal zone, with highly concentrated resources and serving as main hubs for human development [

7]. Significant location value, unique ecological environments, and frequent human activities make bays typical ecologically fragile and environmentally sensitive areas [

8]. The conflict between protection and development is increasingly prominent, making bays a key focus of sustainability research [

5]. Furthermore, bays are home to over 60% of the global population and are regarded as important transportation hubs or economic centers [

9], thus facing greater pressure from carbon emissions.

Land use change profoundly affects soil structure and biological distribution, serving as a key driver of carbon storage variation [

10]. Current research on carbon storage based on land use change can be divided into two main categories: biomass estimation [

10,

11] and modeling approaches [

12,

13]. Biomass estimation is time-consuming and less adaptable, making it difficult to accurately capture long-term carbon storage changes [

10]. Thus, more recent studies tend to use modeling approaches, such as the Forestry and Carbon Cycle of China Model (FORCCHN) model [

14], Multi-scale Comprehensive Assessment Tool - Denitrification-Decomposition (MCAT-DNDC) model [

15], and Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) model [

9]. Compared to InVEST, other models require more detailed data and numerous parameters, which increases their complexity and operational costs [

16]. The InVEST model can estimate carbon storage more accurately and efficiently with fewer data and parameters, making it the most widely used [

17]. For example, Babbar et al. used the InVEST model to assess carbon storage in the Sariska Tiger Reserve from 2000 to 2018 [

18]. Bacani et al. predicted carbon storage in Brazil’s Cerrado eucalyptus production areas for 2030 under different scenarios using InVEST [

19].

Common models for land use prediction include the Cellular Automata (CA) model [

20], CA-Markov model [

21], Future Land Use Simulation (FLUS) model [

22], Conversion of Land Use and its Effects at Small regional extent (CLUE-S) model [

23], and Patch-generating Land Use Simulation (PLUS) model [

24]. CA and CA-Markov are discrete models that lack consideration of external influences and have low operational efficiency. The CLUE-S and FLUS models have limitations in structure and flexibility, making it difficult to handle complex land use scenarios [

25]. The PLUS model, incorporating a Markov chain as well as CA and multi-objective programming (MOP), predicts land use patch evolution by analyzing driving factors of land change. It allows for more comprehensive simulation and prediction of land use change [

26], leading to its widespread use. For example, Zhang et al. used the PLUS model to predict the landscape pattern of the Fujian Delta in 2050 [

27], and Liang et al. explored the drivers of land expansion and landscape changes in Wuhan using the PLUS model [

26].

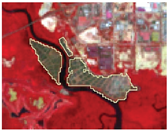

The Johor Estuary is an important transportation hub for both Malaysia and Singapore [

28]. Over the past 50 years, its population has grown rapidly from 2.1 million to 3.7 million—far exceeding the national growth rate of Malaysia (2.6%) [

29]. This surge has driven up demand for food, housing, and other natural resources, resulting in significant changes in land use patterns and carbon storage. However, the frequent clouds and rain typical of South China Sea have limited the acquisition of remote sensing images and other geographic data [

28], leading to relatively little research in the region. Advanced remote sensing technologies are therefore urgently needed as key research tools for coastal studies in this area. Additionally, previous studies on land use and carbon storage have largely relied on existing land use data and have lacked research into the response mechanisms of carbon storage to changes in land use types [

12,

30].

Here, our study aims to investigate the impact mechanisms of land use changes on carbon storage under multiple scenarios in bay areas, using the Johor River Estuary Bay in the South China Sea as a case study and leveraging multi-source remote sensing data. The specific objectives are: (1) To perform land classification through object-based segmentation with Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) texture features and spectral indices. (2) To couple the InVEST-PLUS model to simulate and analyze land use changes in the Johor estuary from 1977-2023, and 2030 under three scenarios (natural development, ecological protection, and economic development). (3) To construct a Carbon Impact (CI) function to quantify the driving effect of each type of land use change on carbon storage. The findings will provide reference for low-carbon sustainable development and future land planning in the Johor estuary and other similar coastal regions.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Case of Changes

Over the past five decades, land use changes in the Johor Estuary Bay have been primarily driven by demographic shifts, policy decisions, and socioeconomic development. The reclamation projects initiated in the 1970s significantly accelerated the reduction of estuarine waters [

29]. During the 1980s, the implementation of the "Johor 2000" plan—jointly developed by the Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA) and the Southeastern Johor Development Authority (SEJDA) aimed to establish Malaysia as a Newly Industrialized Nation (NIN) by the millennium [

6,

36]. This ambitious initiative catalyzed robust economic development in the Johor Estuary Bay region, resulting in a gradual shift of construction areas toward the bay's center. Consequently, extensive forest clearing occurred, particularly in the northern bay where vast forested areas were converted to agriculture land, predominantly oil palm and rubber. Furthermore, since 1990, large-scale infrastructure projects have continued to transform the landscape. Notable examples include the construction of the Linggiu Dam in the upper reaches of the Johor River and the development of the Sungai Johor Bridge spanning the river [

4,

31]. These major engineering projects have consumed substantial areas previously occupied by forests, mangroves, and agricultural lands.

Land use changes have significantly impacted the carbon sequestration capacity of the Johor Estuary Bay. From 1977 to 2023, the degradation of forests and mangroves led to carbon storage reductions of 268,400t and 54,600t, respectively, together accounting for 78.83% of the total carbon loss. Simulation of land use and carbon storage changes under different 2030 scenarios shows that the EPS scenario offers the greatest carbon sequestration capacity, while the EDS results in a substantial decline. Although EPS is more suitable for the bay's low-carbon future, it may reduce regional economic output. Thus, it is important to balance ecological protection and economic growth in future development. As follows:

First, policy interventions can restrict forest and mangrove clearing to maintain carbon sequestration capacity in the Johor Estuary Bay, such as establishing nature reserves or no-logging zones.

Second, economic development should be conducted responsibly, with expansion of construction areas avoiding significant occupation of high-carbon storage land types like forests and mangroves.

Third, increasing the density of existing forests can efficiently and effectively enhance carbon sequestration, requiring less labor, resources, and time compared to restoring already degraded forestland.

5.2. Uncertainties and Limitations

Our land classification used maximum likelihood methods based on Landsat and Sentinel images. However, the frequent cloudy and rainy weather in Johor Estuary Bay limited the availability of high-quality images, making continuous temporal analysis difficult. Consequently, our final land use results did not account for seasonal and phenological changes in the region. Image resolution was also a key factor affecting classification accuracy. In this study, the 30m resolution Landsat images showed edge effects and mixed pixels, particularly affecting boundary delineation between different land use types, such as transition zones between mangroves and water bodies, with Kappa coefficients ranging between 0.86-0.89. The 10m resolution Sentinel images significantly reduced mixed pixels, achieving Kappa coefficients of up to 0.92.

Additionally, the InVEST model used for carbon storage calculation applied uniform carbon coefficients for each land type, without fully accounting for spatial heterogeneity within the same land type. Although this simplification is standard practice, it may underestimate actual carbon storage changes. Furthermore, as this research focused on Johor Estuary Bay, the results have specific regional applicability.

In the future, deep learning and multi-source remote sensing fusion will offer new advantages for land classification and carbon storage assessment. We will also develop dynamic carbon storage assessment methods that integrate remote sensing and process models, and use remote sensing indices (such as NDVI, LAI) and phenological changes for continuous carbon density estimation to avoid within-class simplification.

5. Conclusions

This study used image segmentation to classify land use in Johor Estuary Bay from 1977-2023. Based on the InVEST-PLUS model and multi-scenario simulation, we assessed land use and carbon storage changes in Johor Estuary Bay from 1977-2030. We also constructed a CI function to quantitatively analyze the driving mechanisms of land use changes on carbon sequestration capacity, aiming to provide reference for low-carbon development in Johor Estuary Bay and similar regions. Results show that between 1989-2023, construction land in Johor Estuary Bay expanded approximately 10-fold, while non-construction land decreased, especially forests, water areas, and mangroves, leading to a declining trend in regional carbon storage. The reduction of forests and mangroves was the main cause of carbon sequestration loss. Additionally, comparing the BAU, EPS, and EDS development scenarios, EPS best meets low-carbon development requirements and can serve as a reference for future development models. This study innovatively integrates high-resolution remote sensing classification, scenario simulation, and carbon response index analysis to improve assessment accuracy. However, model parameters have uncertainties such as empirical values, and regional applicability is relatively limited. In the future, deep learning and multi-source remote sensing fusion methods could further improve the accuracy and universality of land classification and carbon storage estimation.