1. Introduction

The utilization of biomass recovered from inedible agricultural wastes for bioplastic production is a promising research avenue, offering significant environmental benefits within a circular economic framework

[

1,

2,

3,

4]. Bioplastics are defined as biodegradable or nonbiodegradable polymers produced from renewable or natural biological sources. However, non-biodegradable bioplastics from biomass and fossil sources fundamentally follow a linear economy model and are not considered to be sustainable. In contrast, biodegradable bioplastics are derived from biomass and support a circular economy by combining short-term biodegradability with the conversion of waste biomass into value-added products [

5,

6].

Bioplastics manufactured from plant biomass provide new functionalities to the resulting product, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, and nutraceutical properties [

7]. During bioplastic production, biomass is typically dried and ground into powder form to reduce bacterial and enzymatic activities, helping to preserve its composition during storage [

8]. Due to its lack of thermoplasticity, this dried and ground biomass cannot be directly converted into bioplastic. Therefore, several methods have been recommended for the digestion and dissolution of the biomass [

2,

4,

9]. Among these, acidic and alkaline hydrolysis are the most used processes [

2]. The resulting plant residue is plasticized with various plasticizers, including glycerol, glycol, xylitol, sorbitol, sugars, amides, urea, formamide, and ethylene-bis-formamide [

10], and is blended with synthetic polymers like polyvinyl alcohol and polylactic acid to enhance both physicochemical properties and biodegradability [

11].

Wheat is one of the most consumed crops in the world [

12,

13]. Wheat belongs to the genus

Triticum spp. The wheat kernel contains 14.5% bran, which is removed during the milling process. A significant amount of wheat bran is produced every year and is primarily used as cattle feed. However, due to low demand and high transportation costs, 90% of the wheat bran remains in landfills, causing environmental pollution [

14].

Wheat bran contains carbohydrates like cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, as well as proteins, minerals such as calcium and phosphorus, silica, acid detergent fibers, and ash. Numerous studies have explored the production of value-added products such as bioplastics, biochar, and others from wheat bran fiber and/or wheat bran starch [

15,

16,

17,

18]. In this study, arabinoxylan, a major polysaccharide, was extracted from wheat bran and used it for bioplastic.

Physico-mechanical properties are essential for evaluating the suitability of bioplastics as sustainable alternatives to conventional plastics. Among these properties, tensile strength, elongation at break, Young’s modulus, water solubility, and thermal and chemical resistance significantly influence the functionality and application of bioplastics in fields like food packaging, agriculture, and biomedical devices [

19]. For example, tensile strength and elongation provide insights into the material’s ability to withstand mechanical stress and deformation, which are crucial for load-bearing or flexible packaging applications [

20].

To assess these characteristics, a range of analytical techniques is employed. The Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is used to detect chemical functional groups, while Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) reveals surface morphology and structural integrity, and tensile testing is evaluated by a Universal Testing Machine (UTM). Additionally, water contact angle (WCA) analysis helps determine hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity. Together, these techniques provide a comprehensive understanding of bioplastic performance and serve as essential tools in material design and improvement.

However, this study focuses on utilizing arabinoxylan derived from wheat bran to develop eco-friendly bioplastics, aiming to reduce the use of commercially available synthetic plastic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Glycerol used as a plasticizer was purchased from Thermo Scientific, USA Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was obtained from Thermo Scientific, USA, and potassium hydroxide (KOH) was obtained from Fisher Chemicals, Belgium. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was bought from Fisher Chemical, USA. The CuSO4.5H2O, commercially known as blue vitriol, was purchased from Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA.

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Wheat Bran Collection and Extraction of Arabinoxylan

Wheat bran was collected from North Dakota Mill, Grand Forks, North Dakota. Upon collecting, the wheat bran was sieved to obtain a uniform size distribution of 2-3 mm of the bran by using a Hamilton Beach blender (Model 609-4, Hamilton Beach Inc.). Arabinoxylan was extracted following the method described in our previous work [

21].

2.2.2. Bioplastic Synthesis

The bioplastic synthesis was conducted using a three-step process, following a slightly modified method described by Mendes et al. [

22]. The first step involved extracting arabinoxylan. The second step includes hydrolysis and plasticization with glycerol. In this phase, arabinoxylan was placed in a beaker containing distilled water. The mixture was heated to 80°C for 20 minutes, after which glycerol was added as a plasticizer to enhance the flexibility and moldability of the plastic. Finally, the mixture was blended with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and stirred continuously at 80°C for an additional two hours until the solution was thickened and turned into a jelly-like slurry. The thick slurry solution was poured into a petri dish and dried overnight in an oven (Thermo Scientific, Heratherm OGS60, made in Germany) at 60°C. The following day, the petri dish was removed from the oven while bioplastic film was formed. The film was then allowed to cool to room temperature and pressed into sheets using a mold. During the process, a specific ratio of materials – arabinoxylan, glycerol, and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) – was used, as detailed in

Table 1.

2.3. Characterization of the Synthesized Bioplastics

2.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR spectral analysis was conducted after extracting arabinoxylan from wheat bran. The FT-IR spectra of the bioplastic film were analyzed after casting, and after two months of the burial of the bioplastic film in soil that used for testing biodegradability. The FT-IR analysis experiment was conducted at the Department of Chemistry, University of North Dakota, USA, using an FT-IR machine model: NICOLETiS5, Thermo Scientific, USA. The spectra, recorded in the 4000–650 cm⁻¹ range, displayed absorption frequency against transmittance (%). Data acquisition resulted in an incidence angle of 45°, a 2 mm sampling area, 16 background scans, an optical resolution of 0.8 cm⁻¹, and data spacing of 0.06 cm⁻¹. The degree of cationization was quantified using the following equation:

where I

1648 and I

1495 represent the peak intensities at 1648 cm⁻¹ and 1495 cm⁻¹, respectively.

2.3.2. Mechanical Properties

Tensile strength (TS) was determined using an Instron Model 5542, made in the USA, following ASTM D412 [

23]. Bioplastic film specimens were cut to 2.7 mm in width, with an average gauge length of 50 mm, and were mounted on the testing apparatus. The tensile test was performed at a crosshead speed of 20 mm/min to evaluate the elastic modulus. Elongation at break (EAB) was calculated by assessing the ratio of the specimen’s final length after failure to its original length under applied tensile stress.

2.3.3. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

The surface morphology of the bioplastic was observed using high-resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy at the Department of RCA Electron Microscopy Core, North Dakota State University, USA. First, the treated plastic samples were cut with scissors and affixed to cylindrical aluminum stubs using silver paint (SPI Products, West Chester, Pennsylvania, USA). A thin conductive layer of gold was then applied to the mounted samples with a sputter coater (Cressington 108Auto, Ted Pella, Redding, California, USA). Imaging was conducted with a JEOL JSM-6490LV scanning electron microscope (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, Massachusetts, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

2.3.4. Film’s Thickness Measurements

The thickness of the film samples was measured by using a digital micrometer with a sensitivity of 0.01 mm, by taking measurements at five randomly selected points. The mean thickness value was then used for subsequent mechanical and optical property analyses.

2.3.5. Film’s Transparency

The transparency of the film samples was evaluated following the slightly modified method described by Mulyono et al [

24]. Bioplastic films were cut into dimensions of 1 cm × 3 cm to fit the width and height of a standard cuvette. Each film sample was attached to the side of the cuvette, and a synthetic polyethylene film served as the control. Absorbance measurements were taken at a wavelength of 800 nm by using a GENESYS 10S UV-VIS Spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific, USA, at Mayville State University. Blue vitriol solution was used for the measurement of absorption. The transmittance (%T) was then calculated using the following equation

And transparency was calculated by using the following formula

Where T is the transmittance at 800 nm and b is the thickness of the bioplastic film in millimeters.

2.3.6. Film’s General Appearance

The visual characteristics of the bioplastic films were evaluated through systematic observation to assess surface texture, uniformity, color, opacity, and the presence of any physical defects such as bubbles, cracks, or warping. Each sample was photographed under standardized conditions—consistent ambient lighting, neutral background, and fixed camera settings—to ensure reliable visual documentation. These images were used to compare the aesthetic and structural integrity of films prepared under different processing conditions or compositions. Visual assessment served as an initial qualitative indicator of film quality and was used alongside analytical techniques to interpret the material’s overall performance and stability.

2.3.7. Water Contact Angle

The way water interacts with the surface is commonly described by two phenomena: hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity. The water contact angle (WCA) is used as a key indicator to evaluate this behavior. Over the years, extensive research has utilized this method to investigate and understand the surface properties [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. In this study, the water contact angle of the synthesized film was measured to evaluate the wearability of the film. A pluggable USB 2.0 Digital Microscope (purchased from Amazon.com) was employed to capture images of water droplets placed on the surface of the film samples. A Ziploc bag and a polyethylene bag collected from local Walmart were used as a reference to compare the water contact angle of the synthesized film. The experiment was conducted at an ambient temperature of 23 °C, a needle width of 0.525 mm, and a droplet volume of 5 µL. The water contact angle was measured using ImageJ software [

30]. Images were taken multiple times for each film, and the best image was selected for analysis.

2.3.8. Water Absorption Percentage

All prepared bioplastic films were cut into dimensions of 2 cm × 2 cm and oven-dried at 60 °C for 24 hours. The initial mass of each film (M₀) was recorded. The samples were then immersed in 50 mL of distilled water for 24 hours at room temperature. After immersion, the films were removed, gently wiped with Pacific Blue Select Multifold Premium 2-Ply Paper Towels by GP PRO (Georgia-Pacific) to remove surface water and weighed to determine the final mass (M₁). The water absorption percentage was calculated using the following formula:

Where Mo and M1 are the initial (dry) mass and the water immersion mass of the film, respectively. The experiment was conducted by the modified method described by Saberi et al [

31].

2.3.9. Effect of Acid

Accurately weighed samples of about 1.0 g of the synthesized bioplastics from arabinoxylan were immersed in sulfuric acid (H

2SO

4) solutions with concentrations of 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%. The samples were continually dried and weighed over certain days to assess weight loss over time, and a photograph was taken after each data collection interval. The experiment was conducted by following the method described by Mostafa et al [

32].

2.3.10. Effect of Alkalis

Accurately weighed samples (synthesized bioplastics from arabinoxylan) of about 1.0 g were taken by using a high-accuracy electronic balance (Denver Instruments XE-100, USA, Serial No NO111601, Max: 100g, d: 0.0001g). The plastic pieces were immersed in potassium hydroxide (KOH) solutions at varying concentrations of 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%. The percentage of weight loss was calculated every second day for ten days, and a photograph was taken after each data collection interval.

2.3.11. Biodegradability Test

The biodegradability experiment was conducted following a modified procedures described by various researchers [

32,

33]. The synthesized bioplastic samples were oven-dried at 45°C for two hours and weighed on a high-accuracy electronic balance. The weighted bioplastic pieces were buried in natural soil obtained from a fallow land surrounding Mayville State University to assess biodegradation. Throughout the experiment, soil moisture content and temperatures were carefully maintained. At four-week intervals, the samples were washed, dried, and weighed to calculate the percentage of weight loss, with a photograph taken after each data collection. For the final data collection, a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) image and a Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectrum were assessed obtained with a photograph for general appearance.

3. Results

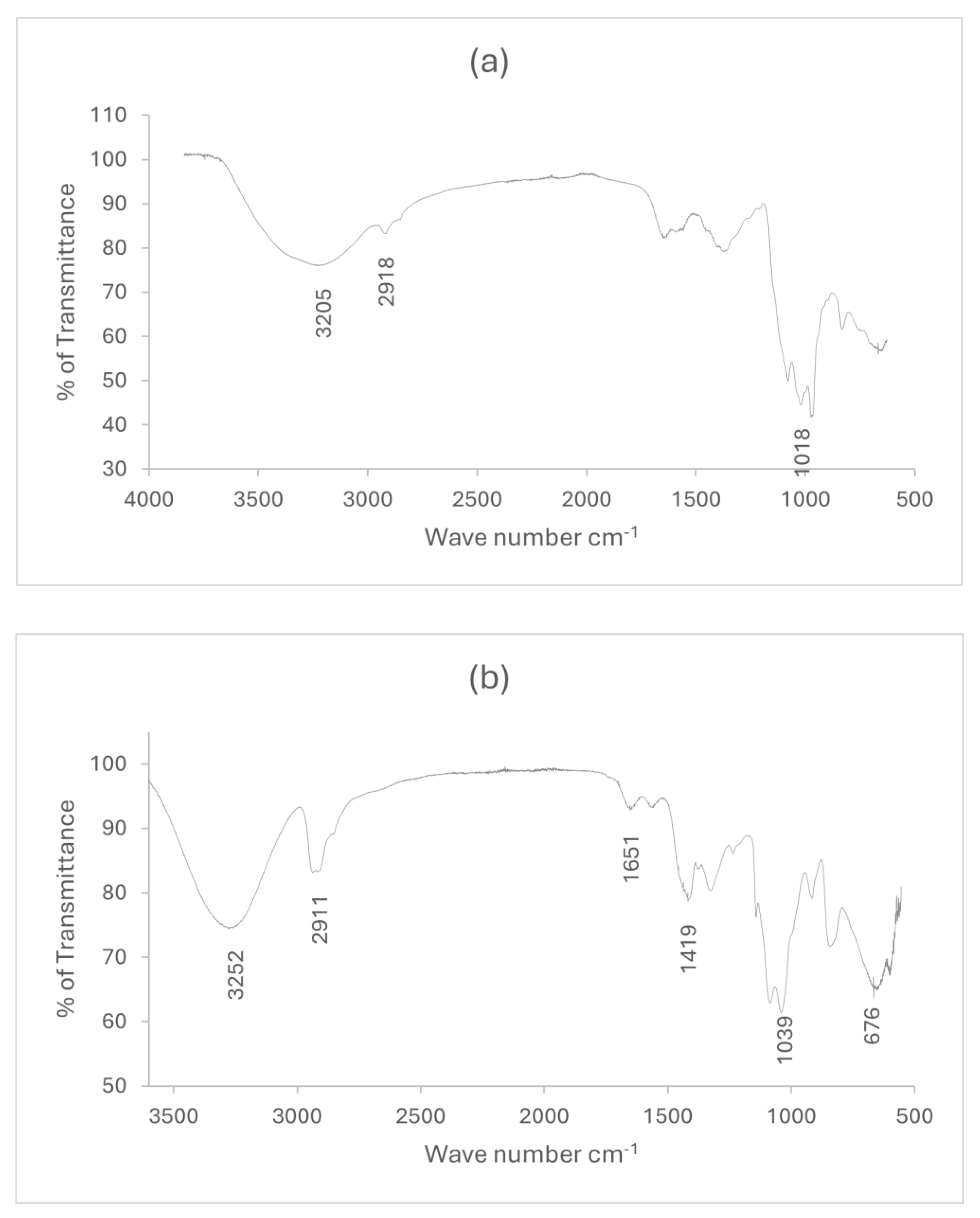

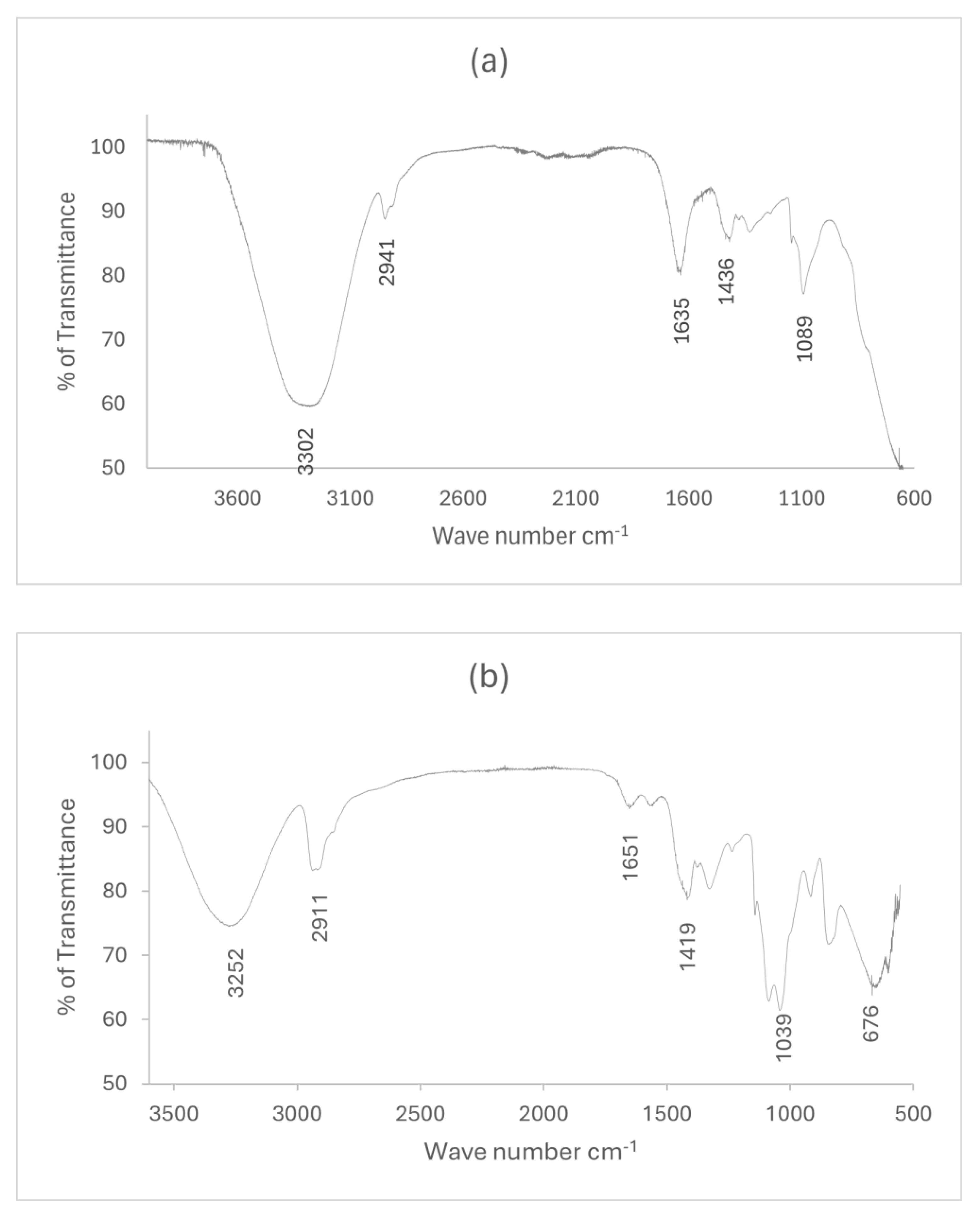

3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

Figure 1 shows the FT-IR spectra of arabinoxylan extracted from wheat bran and the bioplastic made from it. From

figure 1(a), the characteristic spectrum for arabinoxylan was observed at 3205 cm

-1, 2918 cm

-1, and 1018 cm

-1, which correspond to O-H stretching, C-H stretching, and C-OH stretching of glycosidic linkages, respectively.

Figure 1(b) indicates the characteristic peaks of WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic at 3252 cm

-1, 2911 cm

-1, 1651 cm

-1, 1419 cm

-1, 1039 cm

-1, and 676 cm

-1. The broad peaks at 3252 cm

-1 and 2911 cm

-1 indicate the stretching vibrations of O-H and -CH respectively, confirming the interactions of different O-H groups in the arabinoxylan, glycerol, and PVA blend. The peak at 1651 cm

-1 confirms the triglyceride linkage [

34]. The peaks below 1039 cm

-1 indicate the strong molecular hydrogen bonding of hydroxyl group.

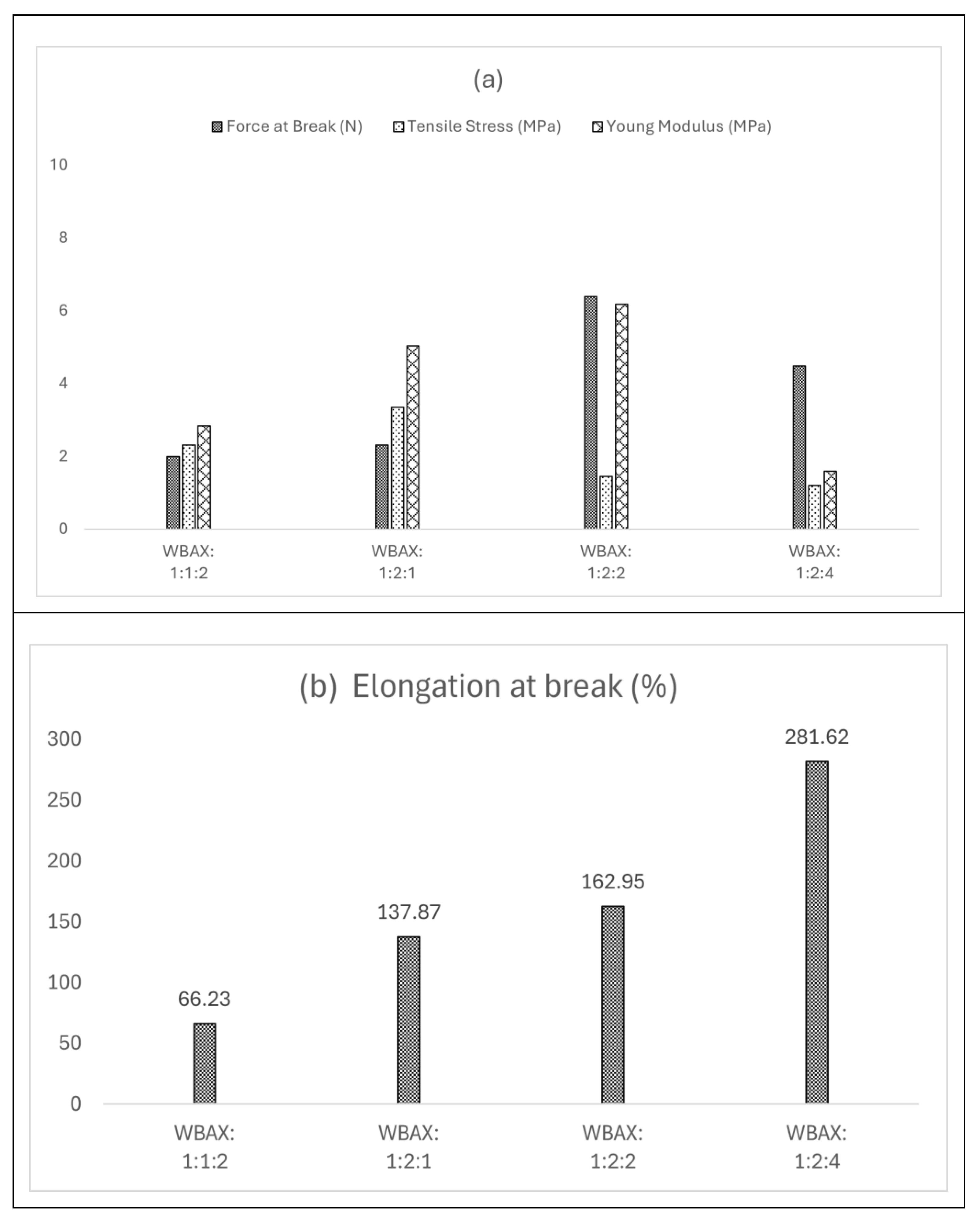

3.2. Mechanical Properties

Tensile stress (TS) and elongation at break (EAB) are essential indicators of a film’s mechanical performance, reflecting its ability to maintain structural integrity under applied stress. The wheat bran extracted arabinoxylan-based bioplastic films of different ratios (WBAX) demonstrated stress at break ranging from 1.2 MPa to 3.34 MPa and an elongation at break (EAB) across from 66% to 281% (

Figure 2). The relatively higher stress values were attributed to the strong interactions between arabinoxylan, polyvinyl alcohol, and glycerol, as a plasticizer and reinforcing agent, thereby enhancing its rigidity and structural stability. However, among the four different bioplastic compositions, the WBAX bioplastic obtained from a matrix blend ratio of 1:2:1 showed the best mechanical performance, with a stress at break of 3.34 MPa and an EAB of 137%. This performance is comparable to that of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and cotton fiber-based bioplastics [

35].

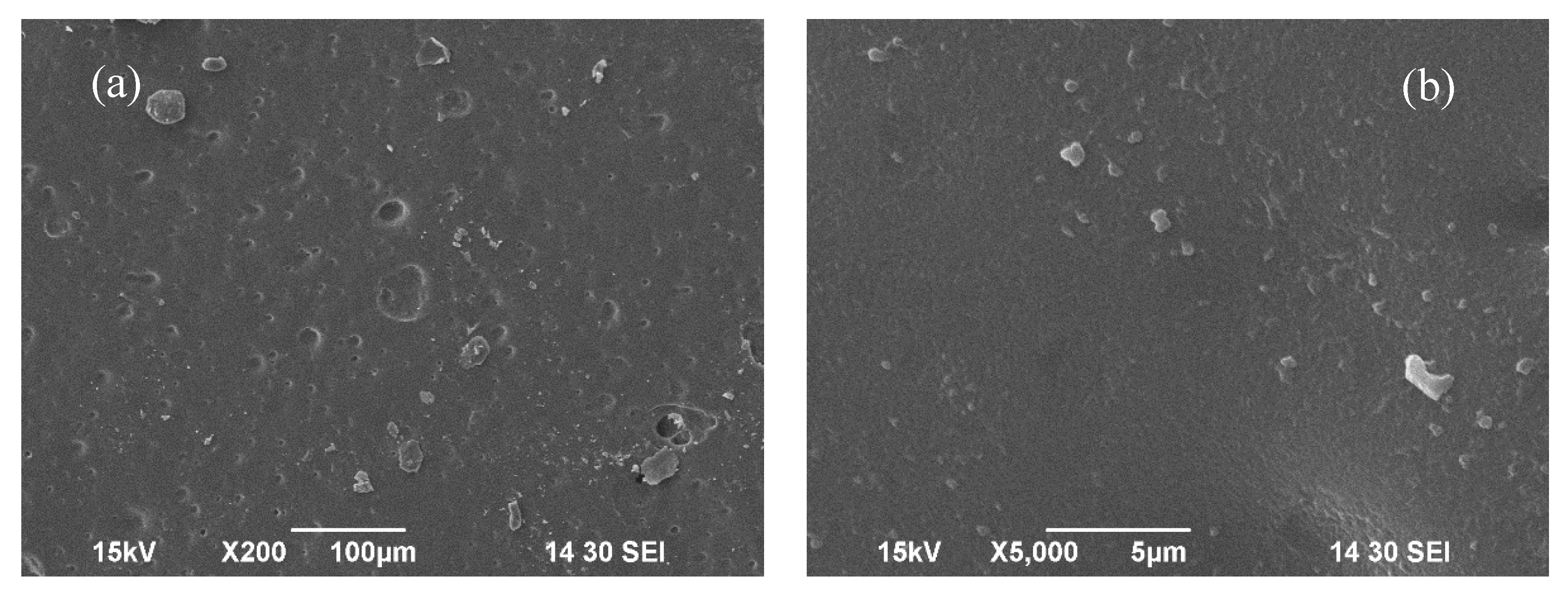

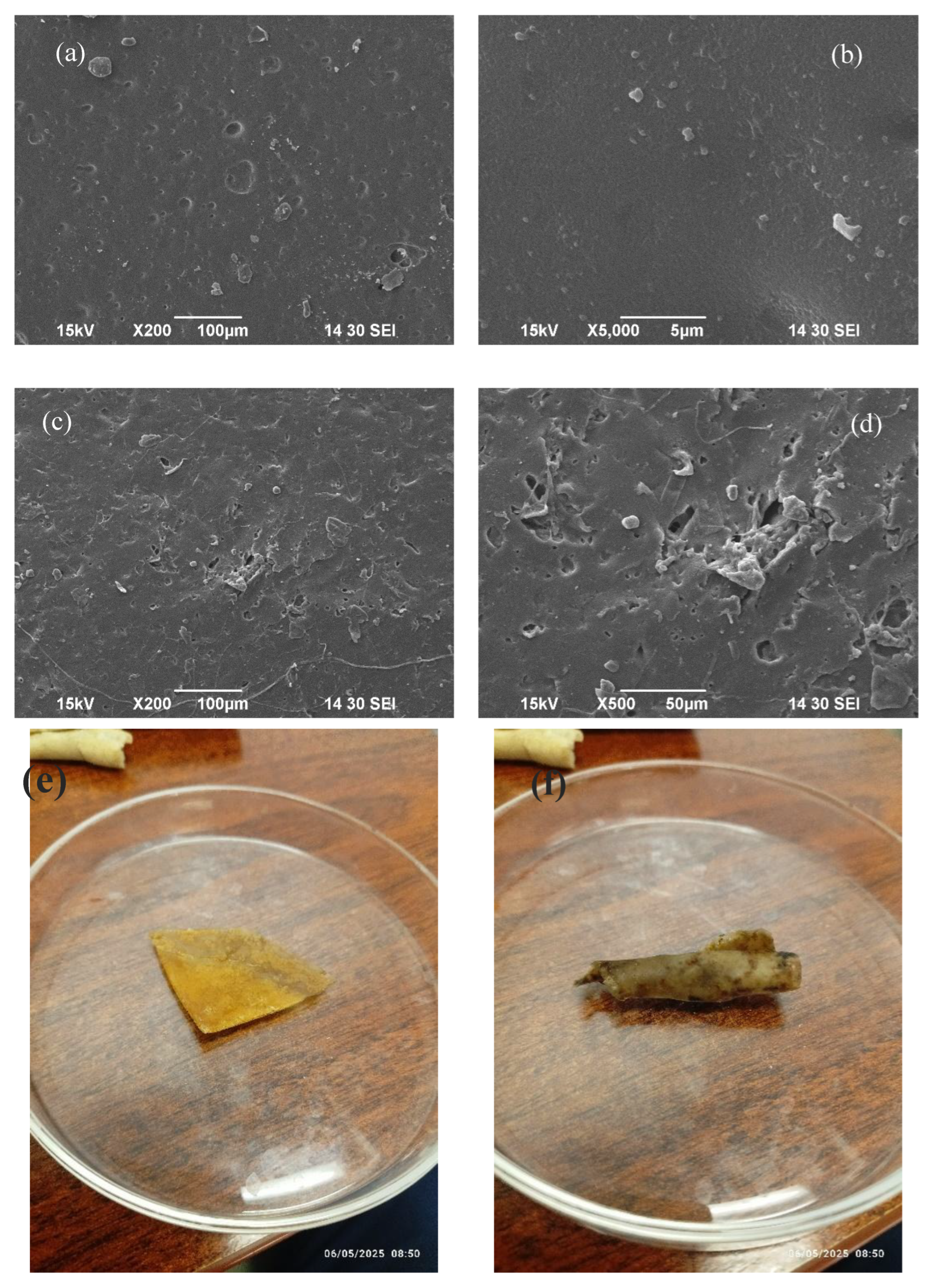

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

Figure 3 shows the surface morphology of WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic at two different resolutions. The SEM image displays the smooth surface of the bioplastic, although it contains some micro-voids. These micro-voids are due to the degree of glycerol dispersion within the plastic matrix. During the gelatinization process, the hydrogen bonds in the long arabinoxylan chains break down, allowing water molecules to penetrate the hydroxyl groups of the arabinoxylan, resulting in the formation of voids and micro-voids. The surface morphology of this bioplastic is found to be similar to the morphology of the polyethylene elastic material studied by Gere et al [

36].

3.4. Film’s Transparency

Table 2 shows that the bioplastic films exhibited lower transparency compared to synthetic polyethylene, which may be due to the presence of fillers and the integral thickness of the bioplastic films. Nonetheless, the PAV-based bioplastic demonstrated superior transparency relative to results reported in previous studies. For instance, Mulyono et al [

24] reported a maximum transparency value of 3.13 for tapioca-based films, whereas the bioplastic films developed in this study achieved a transparency value of 1.50.

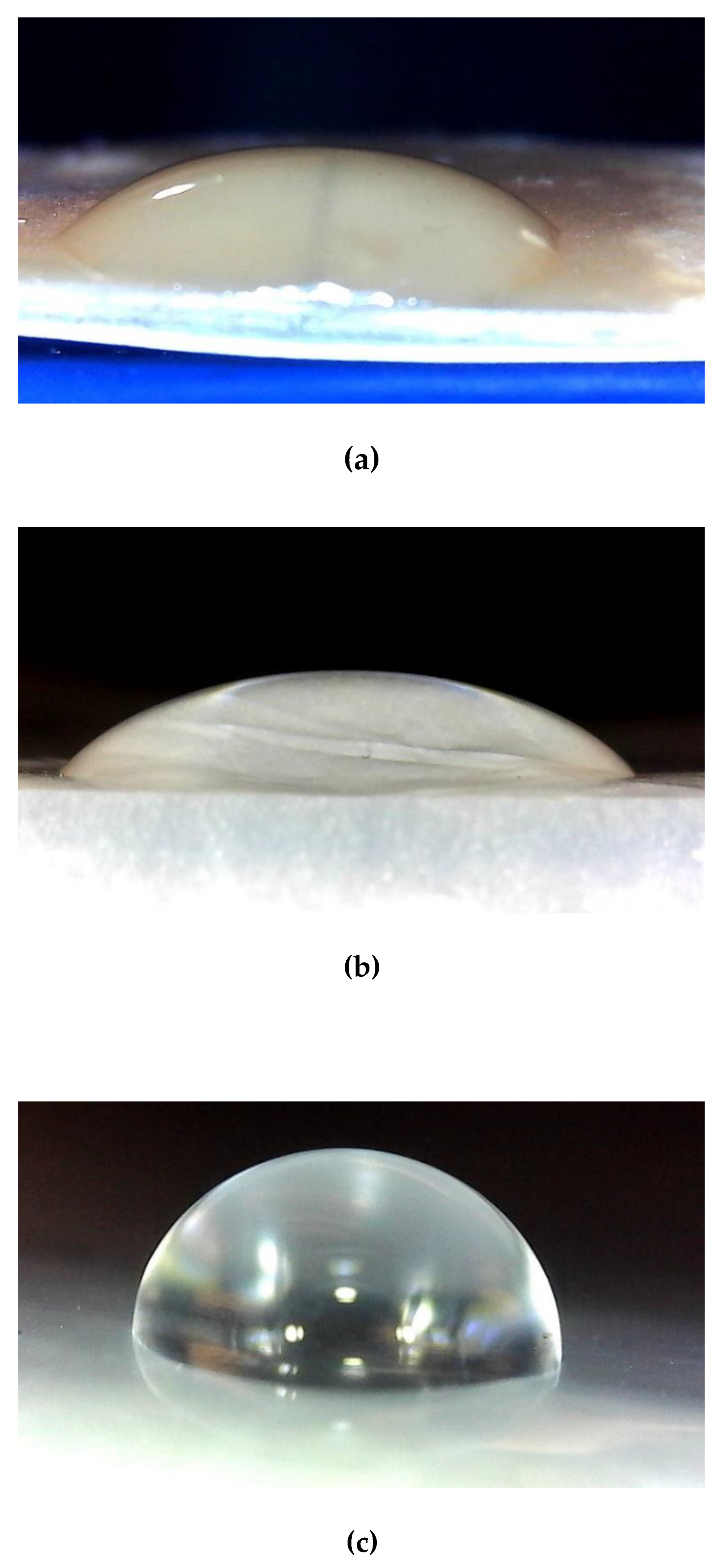

3.5. Water Contact Angle

Figure 4 illustrates the water contact angle measurements, accompanied by images of water droplets on the surfaces of the film samples.

Table 3 presents the water contact angle (WCA) values of the bioplastic film developed in this study, alongside those of a commercially available synthetic plastic bag and selected literature references [

37]. The results indicate that the WBAX bioplastic film exhibits a water contact angle comparable to that of the market plastic, suggesting similar surface wettability characteristics. However, the WCA value of the WBAX bioplastic film remains below 90

0, indicating that it is not truly hydrophobic. For a material to be classified as hydrophobic, its water contact angle must exceed 90°. Therefore, while the WBAX film demonstrates reduced water affinity relative to other bioplastics, it does not meet the threshold for hydrophobicity, implying potential applications where moderate water resistance is sufficient.

3.6. Effect of Acids

The concentration of sulfuric acid has an impact on the weight loss behavior of the bioplastic produced from wheat bran-extracted arabinoxylan. As shown in

Figure 5(a), weight loss increased when the acid concentration was raised from 10% to 20%, indicating that degradation depends on the acid content. At higher concentrations of 30% and 40%, the bioplastic showed complete dissolution, dissolving almost entirely after 2 days in 30%, 40% acid, and after 4 days in 20%. However, in both cases, some residue remained, which makes the solution thicker and slurry, as shown in

Figure 5 (b), indicating that the material did not completely break down. This suggests that high acid concentrations lead to severe degradation, possibly through extensive hydrolysis and disruption of the polymer matrix.

In general, the bioplastics derived from wheat bran-extracted arabinoxylan exhibited strong resistance to acidic conditions at low concentration. Their acid resistance was slightly superior to that of commercial cellulose acetate (CA), which has an environmental resistance factor of three for strong acids, classified as good resistance. This suggests that the bioplastics developed from this study not only offer a sustainable alternative but also performed comparably, if not better, in harsh chemical environments.

3.7. Effect of Alkalis

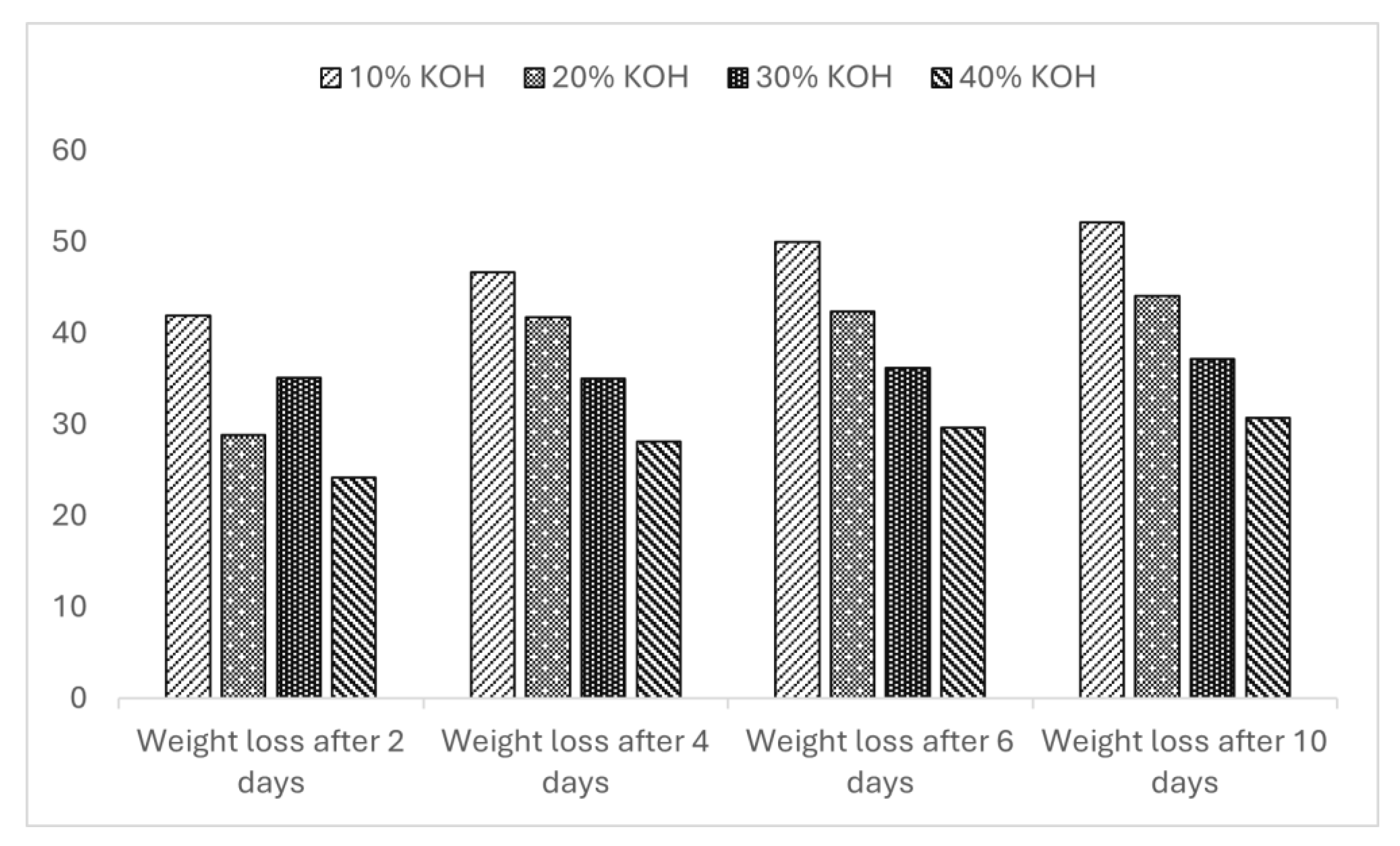

Figure 6 shows the weight loss behavior of bioplastic, produced from wheat bran-extracted arabinoxylan, when treated with different concentrations of potassium hydroxide (KOH) for ten days. After 10 days of exposure to a 40% sodium hydroxide solution, the maximum weight loss was 52% for WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic for 10% KOH.

In comparison, with a 40% KOH concentration, both residues showed a lower weight loss of 31%. The results indicate that the alkali-resistant synthesized bioplastic is nearly identical. However, the bioplastics from this study exhibit strong resistance to alkalis when compared to commercial CA [

32], which has a higher resistance factor (=3) against strong alkalis.

3.8. Water Absorption Percentage

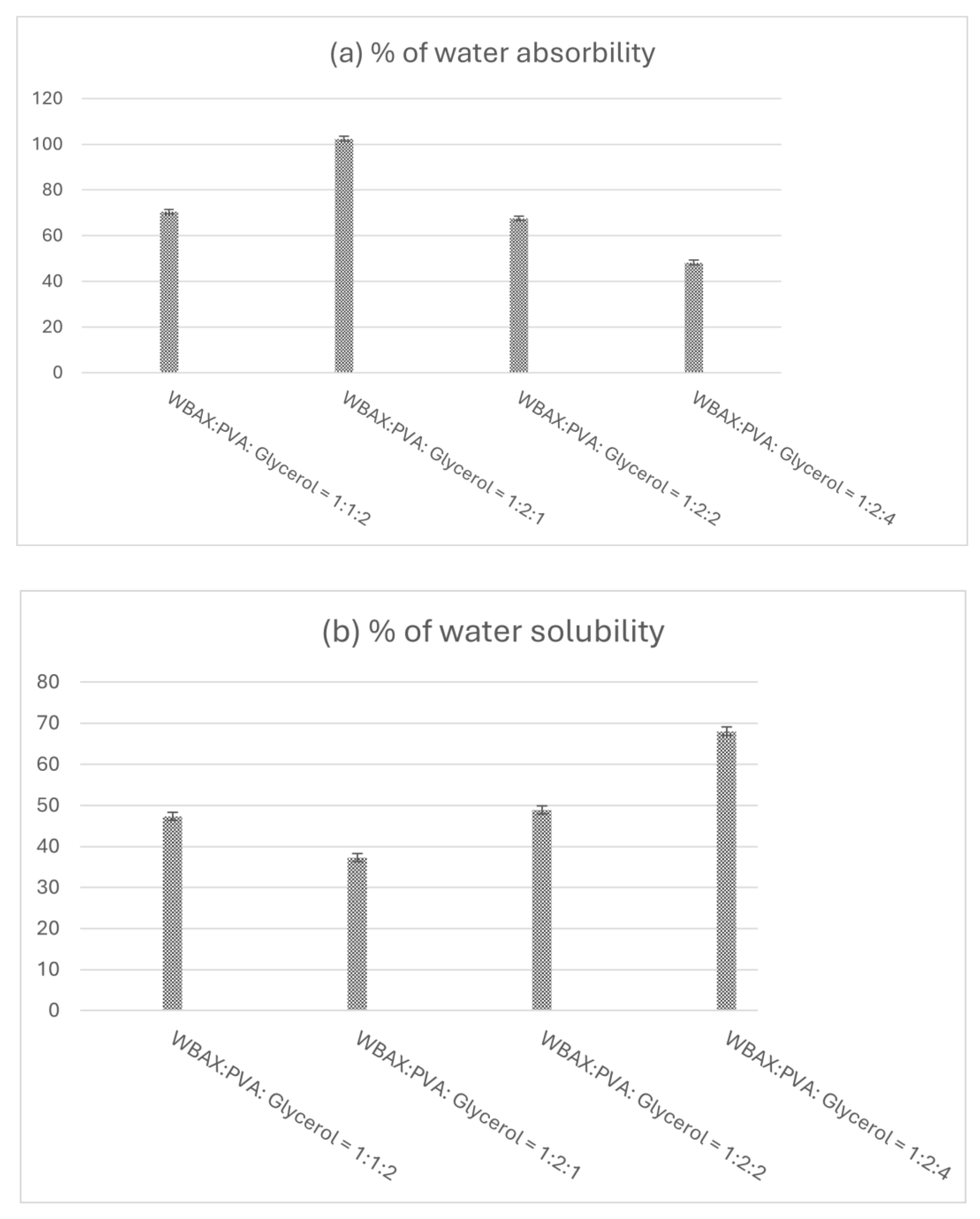

Film water absorption tendency indicates the presence of hydrophilic components in the material.

Figure 7(a) illustrates the water absorption characteristics of the bioplastic film. The bioplastic film’s increased water absorption is due to the presence of PVA, which has water-absorbing qualities. In contrast, those films exhibited a lower tendency, indicating the strong intermolecular forces and cross-linking within the matrix, limiting their interaction with water. Consequently, the bioplastic film at a 1:2:4 ratio displayed the lowest water solubility, while the film at a 1:2:1 proportion showed a moderate level of solubility.

Figure 7(b) illustrates the water solubility behavior of the bioplastic films. Among the tested formulations, the WBAX film with a 1:2:1 ratio exhibited the lowest water absorption, with solubility below 40%. In contrast, the film with a 1:2:4 ratio demonstrated the highest solubility, reaching approximately 70%. The reduced solubility observed in the 1:2:1 film suggests stronger intermolecular interactions and a more compact polymer matrix, which limits water penetration and absorption.

3.9. Biodegradability Analysis

The biodegradability of the WBAX bioplastic film was evaluated through a soil burial testing for two months, and the structural changes were analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR). In

Figure 8 (a,b,c,d), the SEM micrographs revealed notable morphological changes on the film surface after degradation. Compared to the smooth and uniform structure of the undegraded film, the buried samples exhibited cracks, voids, and surface erosion, indicating microbial and environmental activity that contributed to the breakdown of the polymer matrix.

These surface disruptions are characteristic of ongoing biodegradation, where microbial enzymes and soil moisture gradually weaken the film structure. The presence of micro-voids supports the hypothesis that biodegradation initiates through localized enzymatic attack, which leads to fragmentation of the polymer chains and structural disintegration. The physical appearance of the bioplastic film before and after degradation has been displayed in

Figure 8 (e,f).

Further confirmation of chemical degradation was obtained through FT-IR analysis.

Figure 9 shows a comparison of spectra before and after the two-month burial period, revealing significant changes in peak intensities, reflecting the breakdown of functional groups. Most notably, the absorption peak below 1000 cm⁻¹, which corresponds to the hydrogen bonding among the matrix blend, disappeared entirely after degradation. The disappearance of these peaks indicates molecular degradation (hydrogen bond disruption) during the biodegradation process.

4. Discussion

The wheat bran-extracted arabinoxylan-based bioplastic film produced in this study demonstrates a promising combination of mechanical strength, flexibility, chemical resistance, and environmental sustainability, making it a feasible alternative to conventional synthetic plastics, mainly low-density polyethylene (LDPE), which is excessively used in packaging applications worldwide [

38].

Mechanically, WBAX bioplastic shows a tensile strength of 3.34 MPa, which are below the range of commercial LDPE, typically reported to have tensile strengths between 10–30 MPa and an elongation at break of 138%, which are well within the range of commercial LDPE, typically reported to have elongation values from 100% to 600%, depending on processing conditions [

39]. This indicates that WBAX bioplastic could serve well in applications requiring flexibility and moderate mechanical performance, such as food packaging, and others.

Surface wettability analysis shows that WBAX bioplastic has a water contact angle (WCA) of 80°, indicating moderate hydrophilicity. In contrast, LDPE typically has a WCA greater than 95°, making it more hydrophobic [

40]. Although this bioplastic film does not reach the hydrophobic threshold (>90°), its surface properties suggest reduced water affinity, sufficient for many short-term or controlled moisture exposure applications.

The water solubility of WBAX is approximately 40%, emphasizing its partial water resistance while allowing for biodegradation. In comparison, LDPE is virtually insoluble in water and highly resistant to biodegradation, contributing to its long-term environmental persistence [

41]. The biodegradability of WBAX bioplastic is a significant environmental advantage, aligning with the growing demand for sustainable materials.

In terms of chemical resistance, WBAX biofilms show resilience in low concentrations of acid and high concentrations of alkali, supporting their use in chemically variable environments such as agriculture or food packaging. Additionally, the transparency of this biofilm enhances its suitability for applications where visibility or product presentation is significant.

Table 4 shows the comparison of WBAX bioplastic with conventional synthetic plastic.

In conclusion, WBAX bioplastic films show modest performance in terms of mechanical and optical properties while extending the key benefit of environmental compatibility. Although somewhat more hydrophilic than LDPE, their biodegradable and partial water resistance make them suitable for applications where plastic waste reduction is a priority. Future improvements could focus on enhancing hydrophobicity through surface modifications or polymer blending, further expanding their application scope.

5. Conclusions

The eco-friendly, arabinoxylan-based bioplastic derived from wheat bran was successfully synthesized through a multi-step procedure and characterized using a range of analytical techniques and environmental performance evaluations. In terms of mechanical performance, flexibility, optical property, and hydrophobicity, the WBAX bioplastic film in a 1:2:1 blend ratio performs the best, which is comparable to those of LDPE and other biodegradable plastics developed by several researchers. This bioplastic has high resistance to alkali and diluted mineral acid solutions, alongside showing moderate hydrophobicity. The bioplastics show excellent potential for biodegradation, emphasizing their environmental benefits over conventional petroleum-based plastics. Their ability to break down efficiently in natural environments significantly reduces the long-term environmental impact. The satisfactory overall performance of these bioplastics implied potential applications in packaging, food storage containers, and plastic tools, making them a promising alternative to conventional petroleum-based non-biodegradable materials.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript

Author Contributions

The experiment was performed, and the manuscript was prepared by M.A.R.B. under the supervision of K.H., M.K., and K.H. and C. U were involved in concept creation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted at Mayville State University, Mayville, ND, with partial support from the NSF ND EPSCoR ND-ACES program (OIA #1946202).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the support and facilities provided by the NDSU Electron Microscopy Core, which significantly contributed to the characterization aspects of this research. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0619098. We acknowledge the Department of Chemistry, UND, and Mechanical Engineering department NDSU for their contribution to the characterization aspect of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CA |

Cellulose acetate |

| EAB |

Elongation at break |

| FT-IR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| LDPE |

Low-density polyethylene |

| PVA |

Polyvinyl alcohol |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscope |

| TS |

Tensile strength |

| WCA |

Water contact angle |

| WB |

Wheat bran |

| WBAX |

Wheat bran arabinoxylan |

References

- Otoni, C. G.; Avena-Bustillos, R. J.; Azeredo, H. M. C.; Lorevice, M. V.; Moura, M. R.; Mattoso, L. H. C.; McHugh, T. H. Recent Advances on Edible Films Based on Fruits and Vegetables-A Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2017, 16, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, I. S.; Guzman-Puyol, S.; Heredia-Guerrero, J. A.; Ceseracciu, L.; Pignatelli, F.; Ruffilli, R.; Cingolani, R.; Athanassiou, A. Direct Transformation of Edible Vegetable Waste into Bioplastics. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 5135–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, D.; Paul, U. C.; Athanassiou, A. Bio-Based Plastic Films Prepared from Potato Peels Using Mild Acid Hydrolysis Followed by Plasticization with a Polyglycerol. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, D.; Simonutti, R.; Perotto, G.; Athanassiou, A. Direct Transformation of Industrial Vegetable Waste into Bioplastic Composites Intended for Agricultural Mulch Films. Green Chemistry 2021, 23, 5956–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUBIO_Admin. Materials. European Bioplastics e.V. 2024. Available online: https://www.european-bioplastics.org/bioplastics/materials/ (accessed on day month year).

- Aristei, L.; Villani, L.; Ricciardi, W. Directive. The Need to Raise Awareness on Plastic Misuse and Consequences on Health. European Journal of PublicHealth 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, S. G. , Nishad, J., Jakhar, N., & Kaur, C. Food industry waste: mine of nutraceuticals. Int. J. Sci. Environ. Technol 2015, 4, 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Addai, Z. R.; Abdullah, A.; Mutalib, S. A.; Musa, K. H. Evaluation of Fruit Leather Made from Two Cultivars of Papaya. Italian Journal of Food Science 2016, 28, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tang, C.; Yue, Y.; Qiao, W.; Hong, J.; Kitaoka, T.; Yang, Z. Highly Translucent All Wood Plastics via Heterogeneous Esterification in Ionic Liquid/Dimethyl Sulfoxide. Industrial Crops and Products 2017, 108, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Chang, P. R.; Yu, J.; Geng, F.; Ma, X. Relationship of Thermoplastic Starch Crystallinity to Plasticizer Structure. Starch - Stärke 2010, 62, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z. A.; Butt, A. A.; Alghamdi, T. A.; Fatima, A.; Akbar, M.; Ramzan, M.; Javaid, N. Energy Management in Smart Sectors Using Fog Based Environment and Meta-Heuristic Algorithms. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 157254–157267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awika, J. M. ; Vieno Piironen; Bean, S., Ed.; American Chemical Society. Division Of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Advances in Cereal Science : Implications to Food Processing and Health Promotion; American Chemical Society: Washington, Dc, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hensel, G.; Kastner, C.; Oleszczuk, S.; Riechen, J.; Kumlehn, J. Agrobacterium-Mediated Gene Transfer to Cereal Crop Plants: Current Protocols for Barley, Wheat, Triticale, and Maize. International Journal of Plant Genomics 2009, 2009, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemery, Y.; Rouau, X.; Lullien-Pellerin, V.; Barron, C.; Abecassis, J. Dry Processes to Develop Wheat Fractions and Products with Enhanced Nutritional Quality. Journal of Cereal Science 2007, 46, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, N. C.; Rahim, A.; Hillukka, G.; Holter, B.; Kjelland, M.; Hossain, K. Pyrolyzed Biochar from Agricultural Byproducts: Synthesis, Characterization, and Application in Water Pollutants Removal. Processes 2025, 13, 1358–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Mense, A. L.; Brewer, L. R.; Shi, Y.-C. Wheat Bran Layers: Composition, Structure, Fractionation, and Potential Uses in Foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katileviciute, A.; Plakys, G.; Budreviciute, A.; Onder, K.; Damiati, S.; Kodzius, R. A Sight to Wheat Bran: High Value-Added Products. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, K.; Pehlivan, E.; Schmidt, C.; Bahadir, M. Use of Modified Wheat Bran for the Removal of Chromium(VI) from Aqueous Solutions. Food Chemistry 2014, 158, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, O. A.; Mojicevic, M.; Garcia, E. L.; Azeem, M.; Chen, Y.; Asmawi, S.; Brenan Fournet, M. Macro and Micro Routes to High Performance Bioplastics: Bioplastic Biodegradability and Mechanical and Barrier Properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, Avérous; Pollet, E. Environmental Silicate Nano-Biocomposites; London Springer London, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, A.; Mahmud, M.; Koistinen, K.; Davisson, G.; Roeges, B.; Boechler, H. ; Md Abdur Badsha; Khan, R.; Kjelland, M.; Dorsa Fereydoonpour; Quadir, M.; Mallik, S.; Hossain, K. Wheat Bran Polymer Scaffolds: Supporting Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Growth and Development. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.F.; Laís Bruno Norcino; Anny Manrich; Carla, A. ; Oliveira, J. E.; Luiz. Development, Physical-Chemical Properties, and Photodegradation of Pectin Film Reinforced with Malt Bagasse Fibers by Continuous Casting. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurul Nadiah Azmi; Mohd; Noor, S.; Mahmud, J. Nurul Nadiah Azmi; Mohd; Noor, S.; Mahmud, J. Testing Standards Assessment for Silicone Rubber. 2014 International Symposium on Technology Management and Emerging Technologies, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyono, N. , Suhartono, M.T. and Angelina, S. Development of Bioplastic Based on Cassava Flour and Its Starch Derrivatives for Food Packaging. Journal of Harmonized Research in Applied Sciences 2015, 3, 125–3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Duan, Y.; Xin, Z.; Yao, X.; Abliz, D.; Ziegmann, G. Fabrication of an Enriched Graphene Surface Protection of Carbon Fiber/Epoxy Composites for Lightning Strike via a Percolating-Assisted Resin Film Infusion Method. Composites Science and Technology 2018, 158, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, E. M.; Cansoy, C. E.; Zayim, E. O. Optical and Wettability Properties of Polymers with Varying Surface Energies. Applied Surface Science 2015, 350, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Shen, T.; Chen, H.; Lu, J.; Yang, H.-C.; Li, W. Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces (SLIPSs): A Perfect Solution to Both Marine Fouling and Corrosion? Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2020, 8, 7536–7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Bhardwaj, R. Wetting Characteristics of Colocasia Esculenta (Taro) Leaf and a Bioinspired Surface Thereof. Scientific Reports 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Chen, P.; Mu, J.; Yu, Q.; Lu, C. Improvement and Mechanism of Interfacial Adhesion in PBO Fiber/Bismaleimide Composite by Oxygen Plasma Treatment. Applied Surface Science 2011, 257, 6935–6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasband, W. S. ImageJ. Nih.gov. Available online: https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/.

- Saberi, B.; Chockchaisawasdee, S.; Golding, J. B.; Scarlett, C. J.; Stathopoulos, C. E. Physical and Mechanical Properties of a New Edible Film Made of Pea Starch and Guar Gum as Affected by Glycols, Sugars and Polyols. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 104, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, N. A.; Farag, A. A.; Abo-dief, H. M.; Tayeb, A. M. Production of Biodegradable Plastic from Agricultural Wastes. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2018, 11, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R. Biodegradability of Polymers: Regulations and Methods for Testing. Biopolymers Online 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harunsyah; Yunus, M. ; Fauzan, R. Mechanical Properties of Bioplastics Cassava Starch Film with Zinc Oxide Nanofiller as Reinforcement. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2017, 210, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumi, S. S.; Liyanage, S.; Abidi, N. Conversion of Low-Quality Cotton to Bioplastics. Cellulose 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edhirej, A.; Sapuan, S. M.; Jawaid, M.; Zahari, N. I. Effect of Various Plasticizers and Concentration on the Physical, Thermal, Mechanical, and Structural Properties of Cassava-Starch-Based Films. Starch - Stärke 2016, 69, 1500366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, J.; Johannissen, L. O.; Blaker, J. J.; Hay, S. A Machine Learning Model for the Prediction of Water Contact Angles on Solid Polymers. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, K.; Bugusu, B. Food Packaging - Roles, Materials, and Environmental Issues. Journal of Food Science 2007, 72, R39–R55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrady, A. L.; Neal, M. A. Applications and Societal Benefits of Plastics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2009, 364, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodas, D.; Khan-Malek, C. Hydrophilization and Hydrophobic Recovery of PDMS by Oxygen Plasma and Chemical Treatment—an SEM Investigation. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2007, 123, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, J.; Dvorak, R.; Kosior, E. Plastics Recycling: Challenges and Opportunities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2009, 364, 2115–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of (a) wheat bran extracted arabinoxylan, (b) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of (a) wheat bran extracted arabinoxylan, (b) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic.

Figure 2.

Mechanical properties of WBAX bioplastic at different ratios.

Figure 2.

Mechanical properties of WBAX bioplastic at different ratios.

Figure 3.

SEM image of (a) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic at 200x resolution, (b) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic at 5,000x resolution.

Figure 3.

SEM image of (a) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic at 200x resolution, (b) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic at 5,000x resolution.

Figure 4.

Water Contact Angle of (a) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic, (b) Walmart plastic bag, (c) Ziploc plastic bag.

Figure 4.

Water Contact Angle of (a) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic, (b) Walmart plastic bag, (c) Ziploc plastic bag.

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of acid concentration and treatment duration on weight loss, (b) the thicker and slurry solution after 2 days of dissolution (right side), 40% acid solution (left side).

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of acid concentration and treatment duration on weight loss, (b) the thicker and slurry solution after 2 days of dissolution (right side), 40% acid solution (left side).

Figure 6.

Effect of alkali concentration and treatment duration on weight loss.

Figure 6.

Effect of alkali concentration and treatment duration on weight loss.

Figure 7.

Water Absorption property of WBAX bioplastics (a) % of water absorbability, (b) % of water solubility.

Figure 7.

Water Absorption property of WBAX bioplastics (a) % of water absorbability, (b) % of water solubility.

Figure 8.

SEM image of (a) WBAX 1:2:1 before degradation at 200x resolution, (b) WBAX 1:2:1 before degradation at 500x resolution, (c) WBAX 1:2:1 after 2 months of natural degradation at 00x resolution, (d) WBAX 1:2:1 after 2 months of natural degradation at 500x resolution, (e) physical appearance of WBAX 1:2:1 before degradation, (f) physical appearance of WBAX 1:2:1 after degradation.

Figure 8.

SEM image of (a) WBAX 1:2:1 before degradation at 200x resolution, (b) WBAX 1:2:1 before degradation at 500x resolution, (c) WBAX 1:2:1 after 2 months of natural degradation at 00x resolution, (d) WBAX 1:2:1 after 2 months of natural degradation at 500x resolution, (e) physical appearance of WBAX 1:2:1 before degradation, (f) physical appearance of WBAX 1:2:1 after degradation.

Figure 9.

FT-IR spectra of (a) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic after 2 months of degradation, (b) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic before degradation.

Figure 9.

FT-IR spectra of (a) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic after 2 months of degradation, (b) WBAX 1:2:1 bioplastic before degradation.

Table 1.

The composition ratio of the bioplastic blend.

Table 1.

The composition ratio of the bioplastic blend.

| Title |

Wheat bran arabinoxylan (WBAX) |

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) |

Glycerol |

| WBAX 1:1:2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| WBAX 1:2:1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

| WBAX 1:2:2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

| WBAX 1:2:4 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

Table 2.

Transparency of bioplastic films.

Table 2.

Transparency of bioplastic films.

| Film type |

Absorbance |

Transmission% |

Thickness |

Transparency |

| WBAX bioplastic film |

1.23 |

5.92 |

0.19 |

1.50 |

| CPS bioplastic film |

1.25 |

5.60 |

0.17 |

1.52 |

| Ziploc plastic bag |

0.05 |

89.23 |

0.02 |

3.57 |

| Walmart plastic bag |

- |

- |

- |

3.78 |

| tapioca-based films, |

- |

- |

- |

3.13 |

Table 3.

Water Contact Angle (WCA) of different plastics.

Table 3.

Water Contact Angle (WCA) of different plastics.

| Film type |

Water Contact Angle (degree) |

| WBAX bioplastic film |

75.80 |

| Ziploc plastic bag |

124.83 |

| Walmart plastic bag |

76.78 |

| PLA/starch/lecithin film |

59.250 |

Table 4.

Comparison of physico-mechanical properties of WBAX bioplastic and LDPE.

Table 4.

Comparison of physico-mechanical properties of WBAX bioplastic and LDPE.

| Property |

WBAX Bioplastic |

LDPE (Synthetic Plastic) |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) |

3.34 |

10–30 |

| Elongation at Break (%) |

138 |

100–600 |

| Water Contact Angle (°) |

80 |

>95 |

| Water Solubility (%) |

~40 |

<1 |

| Biodegradability |

Yes |

No |

| Acid Resistance |

Low concentration |

Moderate |

| Alkali Resistance |

High concentration |

Moderate |

| Transparency |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).