1. Introduction

Persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) is the primary cause of cervical cancer, with HPV types 16 and 18 being the most frequently detected [

1,

2]. In response to the limitations (poor sensitivity) of cytology-based screening, molecular tests, detecting HPV DNA or mRNA, are increasingly used for primary screening due to their higher clinical sensitivity for identifying women at risk of high-grade cervical lesions (CIN2/3) [

3,

4,

5].

Among molecular tests, mRNA-based assays provide a key clinical advantage by detecting E6/E7 oncogene transcripts, which are indicators of transcriptionally active and potentially transforming HPV infections [

5,

6,

7]. This improves diagnostic specificity and risk stratification compared to DNA-based assays, which may detect transient, clinically insignificant infections [

5,

8,

9,

10]. However, mRNA assays have shown slightly lower analytical sensitivity compared to DNA-based platforms [

8,

11], and comparative studies such as that by Dockter et al. have highlighted this trade-off when evaluating mRNA-based detection against widely used DNA assays like Qiagen’s Hybrid Capture 2 test [

11].

DNA-based assays such as the Abbott RealTime High Risk HPV, Hybrid Capture 2, and Roche Cobas 4800 are widely validated and commonly used [

9,

10]. These platforms typically target conserved regions of the viral genome, often reporting HPV 16 and 18 separately due to their high oncogenic risk [

8,

9,

10]. However, in high-burden, resource-limited settings, their limited specificity may result in over-referral and overtreatment [

10,

12].

Furthermore, as HPV vaccination coverage expands, shifts in genotype prevalence, including possible type replacement or unmasking of non-vaccine types, necessitate ongoing molecular surveillance [

8,

12]. This is particularly critical in sub-Saharan Africa, where types such as HPV 33, 35, 45, 52, and 58 are common [

12,

13,

14], with HPV 35 sometimes competing with HPV 16 in cervical cancer cases [

14,

15,

16].

To support such surveillance and improve screening, extended genotyping platforms are increasingly used [

10]. The Seegene Allplex™ II HPV28 assay enables the detection of 28 HPV genotypes via multiplex real-time PCR, offering high-throughput processing, automation, and strong agreement with FDA-approved assays [

8,

17].

Despite these advancements, the inability of DNA assays to differentiate between transient and transforming infections limits their clinical performance [

11]. mRNA assays such as the APTIMA

® HPV test have emerged as more specific tools for identifying clinically significant infections [

6,

7,

9]. Large trials like ESTAMPA have reinforced the value of molecular screening in diverse populations [

19], and the World Health Organization now recommends a global shift to HPV-based screening, particularly in resource-limited settings [

20].

This study assessed the screening performance of the APTIMA HPV mRNA assay with two DNA-based platforms, the Seegene Allplex™ HPV28 and Abbott RealTime HR-HPV assays, in cervical samples from a South African cohort. Previous studies, including a screen-and-treat trial by Sørbye et al. [

21], have demonstrated the utility of mRNA-based testing (APTIMA) in improving screening specificity and reducing overtreatment in South African women. However, while comparisons between mRNA and DNA-based assays (such as Cobas or Abbott) have been reported [

8,

10,

11,

22], there remains a lack of published evidence directly comparing mRNA assays with extended genotyping platforms like the Seegene Allplex™ HPV28. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the analytical performance of the Seegene and APTIMA platforms. By evaluating relative sensitivity and specificity for detecting 14 HR-HPV types, this study aims to address that gap and inform evidence-based screening strategies that improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce overtreatment, and support cervical cancer prevention in high-prevalence, resource-constrained settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size

A non-probability convenience sampling strategy was utilized, with participants enrolled until the target sample size was reached. The sample size was calculated using Epi Info version 7.1.5 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, United States of America), to ensure 90% statistical power and 95% confidence, initially determined to be 416 but later increased to 527 to minimize potential study participant loss and information errors.

2.2. Study Sample and Sample Collection

The study sample consisted of 527 women aged 18 years and older who attended Termination of Pregnancy (TOP) and gynecology oncology clinics at the Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital (DGMAH) in Ga-Rankuwa between January 2016 to December 2018. The women sought various gynecological services, including family planning, pregnancy termination, Pap smears requested by attending clinicians, colposcopy, large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ), and post-LLETZ review. Eligible participants had an intact cervix, gave informed consent, and completed a questionnaire. Women were excluded if they had a history of hysterectomy, were menstruating at the time of sampling, or had missing key data or compromised specimens. Participants were recruited from clinic waiting areas and enrolled after providing written informed consent. They then completed a questionnaire. Cervical samples (including endocervical, ectocervical, and transformation zone cells) were collected by healthcare workers using the Cervex-Brush® Combi and a speculum (Rovers Medical Devices, Oss, The Netherlands). Each brush was immediately rinsed into a vial containing 20 mL ThinPrep® PreservCyt® solution (Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA), and then discarded. The vials were transported to the Virology Department at Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University (SMU), where they were stored at room temperature until further processing and long-term storage and testing.

2.3. Sample Processing

Upon arrival at the department, 2 mL of each sample were aliquoted into 2 mL tubes for HPV testing, while the rest of the samples were used for liquid based cytology testing.

2.4. DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted using the Abbott mSample Prep System DNA on the Abbott m2000sp platform (Abbott Molecular Diagnostics, Inc., Branchburg, NJ, USA). For each sample, 800 μL of PreservCyt cervical sample was aliquoted into labeled Abbott sample tubes and loaded onto the m2000sp. The extraction yielded 100 μL of DNA eluent per sample, which was transferred into a 96-deep-well plate, then into 96-PCR plates on the m2000sp for Abbott RealTime High Risk HPV testing. The extraction process included internal positive and negative controls to validate assay performance and monitor for contamination or technical error.

2.5. HPV DNA Detection and Genotyping

2.5.1. The Abbott RealTime High-Risk HPV Assay

The Abbott RealTime High-Risk HPV assay (Abbott Molecular GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden, Germany) is a real-time PCR-based test designed to detect 14 HR-HPV types by targeting the conserved L1 gene of HPV. It individually identifies HPV16 and HPV18, while the remaining 12 types (HPV 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) are collectively reported as “Other High Risk”. Amplification and genotyping were performed on the Abbott m2000rt system using 25 μL of extracted DNA per sample, in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. To ensure sample integrity and adequacy, the assay included an internal control that detects the endogenous human beta-globin sequence. Test results were reported as either negative or positive, with positive results further classified as HPV16, HPV18, or Other High Risk. Remaining eluates were aliquoted into labeled 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes and stored at –70 °C for subsequent testing with the Seegene Allplex™ HPV28 assay.

2.5.2. The Allplex™ II HPV28 Detection Assay

The Allplex™ II HPV28 Detection assay (Seegene, Seoul, Korea) was performed in two tubes to permit the simultaneous amplification, detection and differentiation of target nucleic acids for 19 HR HPV types (16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 69, 73, 82) and nine LR HPV types (6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Five micro liters of the extracted samples were used for HPV detection. The human beta globin gene served as an Internal Control (IC) to monitor nucleic acid isolation and assess for potential PCR inhibition. Although this assay detects 28 HPV types, only the 14 HR types common to both assays are reported for direct comparison. Results were reported as positive or negative for the detected HPV genotype with corresponding CT values together with IC for that sample.

2.6. HPV E6/E7 mRNA Detection

HPV E6/E7 mRNA was tested using the APTIMA HPV assay on the PANTHER system (Hologic Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA, USA). One milliliter of the PreservCyt cervical sample was transferred into an APTIMA Specimen Transfer tube containing lysis solution and then tested. The APTIMA HPV assay detects E6/E7 viral mRNA from 14 HR HPV types (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68). The assay uses a non-infectious RNA transcript as an internal control to monitor nucleic acid capture, amplification, and detection. Results were reported as positive or negative for mRNA, without specifying the genotype present.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata version 18.5 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Assay performance was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, and Cohen’s kappa (κ) statistic to assess agreement, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Agreement strength was interpreted as poor (κ ≤ 0.20), fair (κ = 0.21–0.40), moderate (κ = 0.41–0.60), good (κ = 0.61–0.80), or very good (κ = 0.81–1.00). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to assess discriminatory ability, using the Abbott RealTime High Risk HPV assay as the reference test. Area under the ROC curve (AUC) values were reported with 95% CIs. Prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% CIs were calculated to compare detection rates across assays. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Analytical Performance of mRNA vs DNA-Based HPV Assays

Overall HR-HPV prevalence, based on the 14 HR-HPV types shared across the Abbott RealTime, Seegene Allplex™ HPV28, and APTIMA assays, was 48.2% with Abbott, 53.7% with Seegene, and 45.2% with APTIMA (

Table 1). These proportions form the basis for the comparative performance assessment. The Seegene HPV DNA and APTIMA HPV mRNA assays were evaluated against the Abbott HPV DNA assay, which served as the comparator assay. Although the Seegene assay detects 28 HPV types, the analysis was restricted to the 14 HR-HPV types common to all three platforms.

As shown in

Table 1a, Seegene demonstrated a sensitivity of 82.3% (95% CI: 77.3–86.5) and specificity of 81.6% (95% CI: 76.5–86.0), with an overall agreement of 82.9% and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.70 (95% CI: 0.60–0.76), indicating good concordance with Abbott. In comparison, the APTIMA assay (

Table 1b) showed higher sensitivity at 89.9% (95% CI: 85.4–93.4) and specificity at 86.2% (95% CI: 81.6–89.9), with an overall agreement of 87.9% and a kappa value of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.73–0.85), reflecting strong agreement with Abbott. These findings suggest that the APTIMA assay provides comparable sensitivity to DNA-based methods, while achieving higher specificity, which is particularly important for minimizing unnecessary follow-up in screening settings.

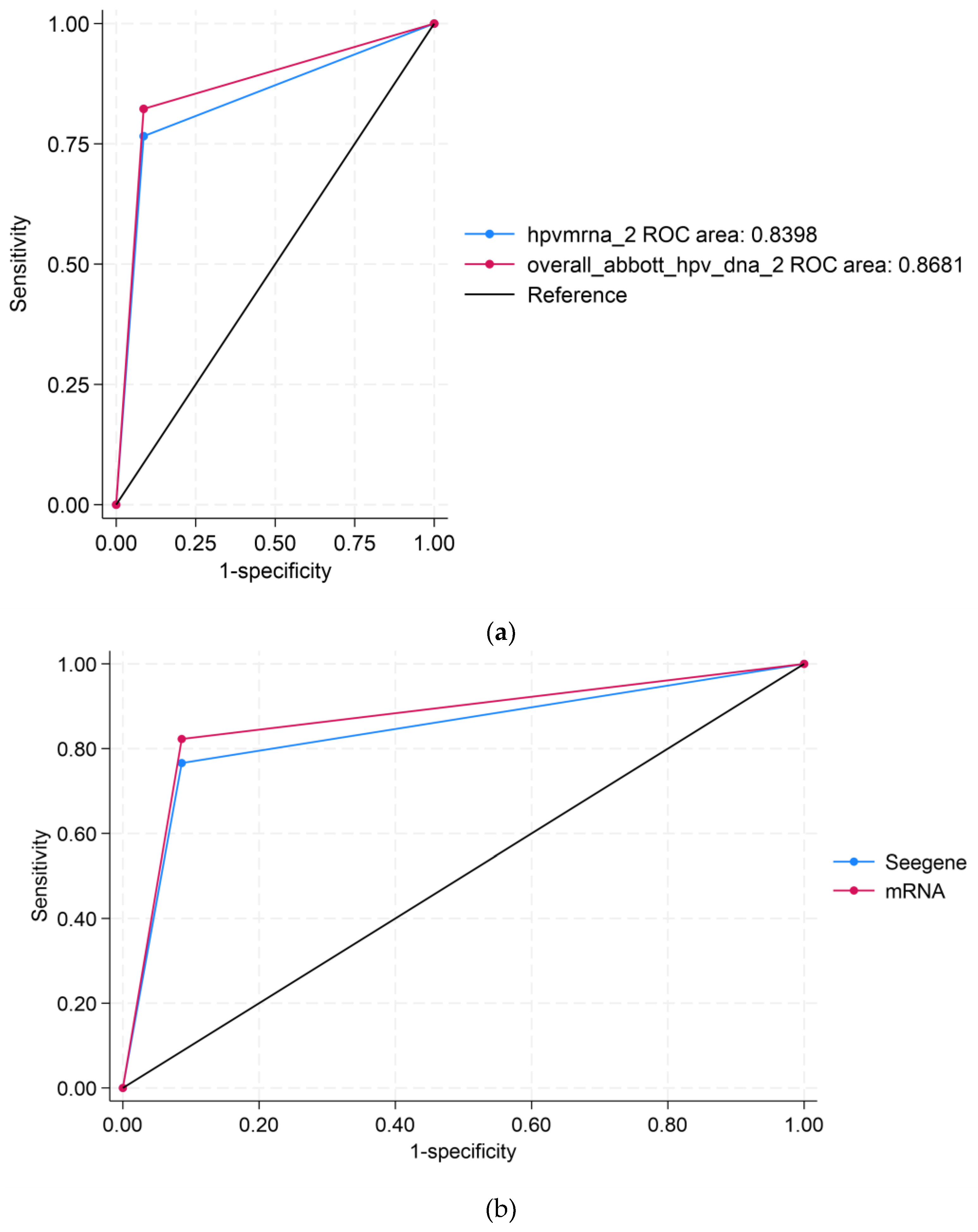

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analyses

Figure 1 displays the ROC analyses using Abbott as the reference test. Panel (A) compares APTIMA to Abbott, showing an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.8398 for APTIMA and 0.8681 for Abbott, indicating strong overall concordance. Panel B compares APTIMA and Seegene assays. APTIMA showed a marginally higher AUC (0.8804) than Seegene (0.8681), though the difference was not statistically significant (

p = 0.0563). These ROC comparisons reflect analytical agreement and are not measures of clinical diagnostic accuracy, as no histologic reference standard (e.g., CIN2/3) was available.

3.2. Detection Concordance of HR-HPV Types

Table 2 presents detection concordance for the 14 HR-HPV genotypes (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) targeted by all three assays. Seegene reported the highest positivity rate (53.7%), followed by Abbott (48.2%) and APTIMA (45.1%).

The Seegene assay identified more positives, likely due to broader analytical sensitivity. APTIMA identified fewer positive cases, consistent with its targeting of E6/E7 oncogene transcripts, which may better reflect transcriptionally active infections. Notably, 4.6% were APTIMA-positive but Abbott-negative, and 1.9% were APTIMA-positive but Seegene-negative (

Table 2). These cases are unlikely to be false positives, as APTIMA detects viral oncogene expression, which may be missed by DNA assays if viral DNA is present at low levels or in a latent state. Thus, the mRNA-positive, DNA-negative samples likely represent true infections with active transcription missed by DNA-based assays. On the other hand, each DNA assay also identified a small number of positives not detected by APTIMA, which may reflect the detection of latent or transient infections without transcriptional activity. These discrepancies highlight key methodological differences across platforms and have important implications for clinical interpretation and follow-up strategies

3.3. HPV Genotype Distribution and Implications for Vaccine Coverage

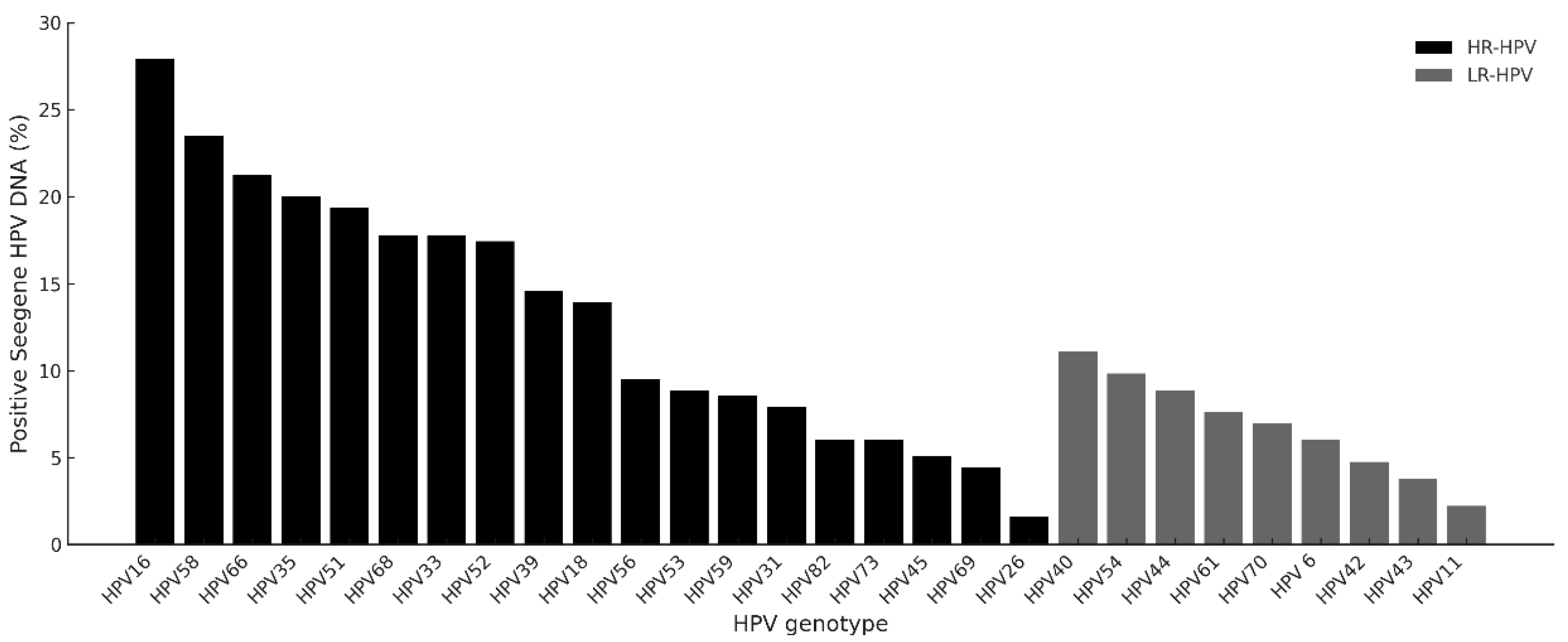

The overall genotype distribution detected by the Seegene assay is shown in

Figure 2. Among HR-HPV types, HPV16 was the most prevalent (27.9%), followed by HPV58 (23.5%), HPV66 (21.3%), and HPV35 (20.0%). Low-risk types were less frequent, with HPV40 (11.1%) being the most common among them. Notably, HPV6 and 11, targeted by current vaccines, were rarely detected, suggesting regional variation or population-specific genotype distribution.

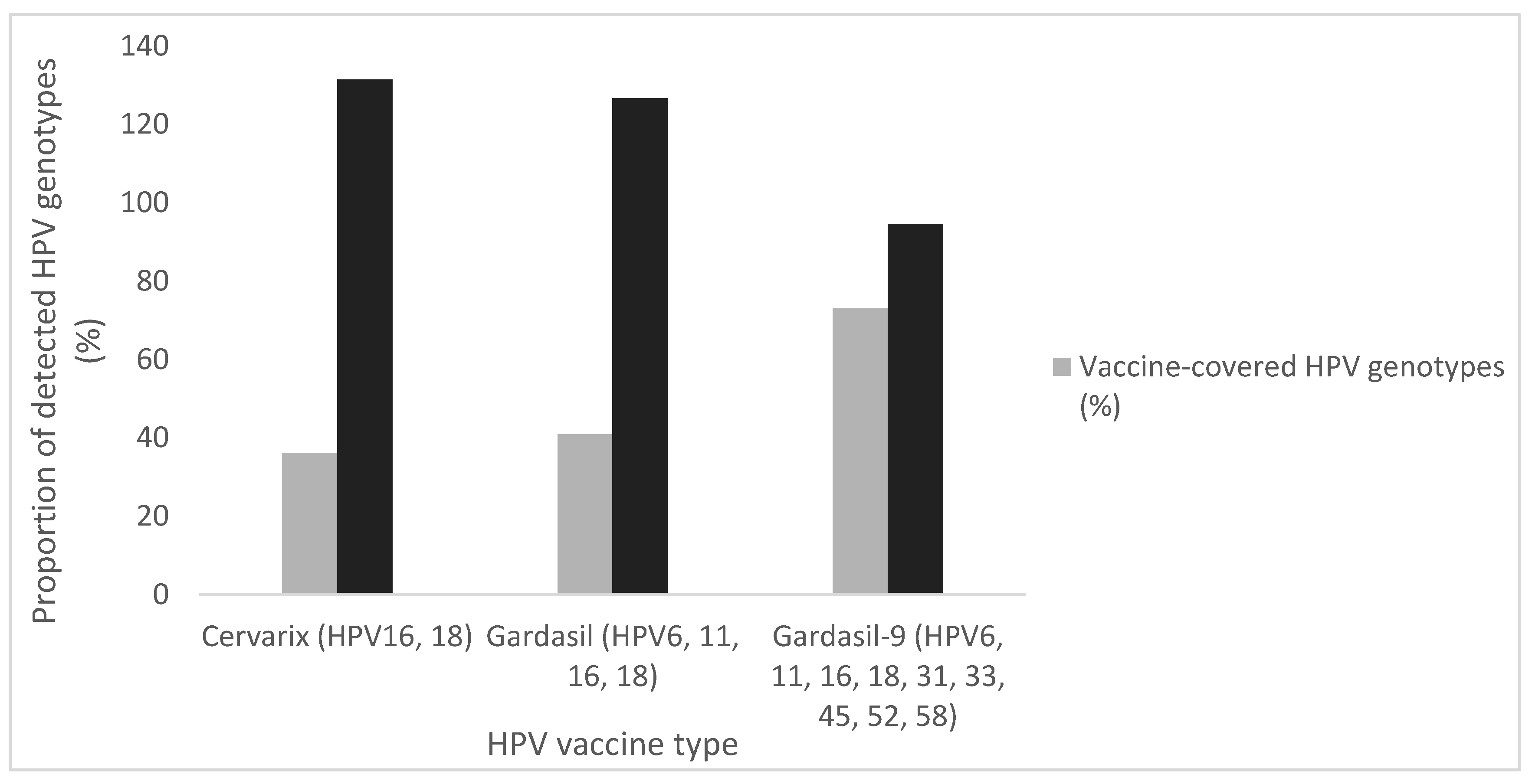

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of HPV genotypes detected among the 315 HPV-positive individuals across all the tests, categorized according to coverage by currently licensed HPV vaccines. Based on the detected genotypes, Cervarix, which targets HPV16 and 18, would have provided protection to 36.2% of individuals. The inclusion of LR-types HPV6 and 11 in Gardasil extends this coverage slightly to 41.0%. Gardasil-9, which also targets five additional HR HPV types (HPV31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), would have increased the potential vaccine coverage to 73.0% of the cases.

3.4. Sociodemographic Predictors of HR-HPV Infection

Table 3 summarizes the HPV detection rates across the three assays, along with socio-demographic associations. The highest overall HPV prevalence was observed with the Seegene DNA assay (60.0%, 315/525), followed by Abbott (48.2%, 254/527), and APTIMA (45.0%, 237/527). This trend likely reflects the broader analytical detection of Seegene and the mRNA higher specificity of APTIMA, which targets transcriptionally active infections.

Across all assays, HPV positivity was statistically associated with employment and marital/relationship status (p < 0.001). Women who were unemployed and single had notably higher infection rates. No statistically significant associations were found for age, ethnicity, province, or residential location although there was a difference in number of participants by province and location where majority were from Gauteng and Semi-Urban.

4. Discussion

HPV DNA-based testing has become a valuable tool in cervical cancer screening due to its high sensitivity compared to traditional cytology. However, its lower specificity poses a challenge because it cannot reliably differentiate between infections that will resolve on their own and those that persist and carry a higher risk of progressing to disease. Distinguishing persistent infections is crucial to minimize unnecessary worry for women who test positive and to avoid overwhelming healthcare systems with follow-ups and treatments for cases unlikely to advance. This concern is especially important in settings with limited resources, such as South Africa, where careful allocation of healthcare services is essential. South Africa’s recent implementation of HPV testing in its national screening program highlights the importance of using diagnostic methods that offer both accuracy and practical clinical value.

To support such context-sensitive screening strategies, this study compared the analytical performance of three HPV assays, APTIMA (mRNA-based), Seegene, and Abbott (both DNA-based), using the Abbott assay as the reference comparator. APTIMA demonstrated higher sensitivity (89.9%), and specificity (86.2%) compared to Seegene (82.3% and 81.6%, respectively). Although APTIMA reported a lower HR-HPV positivity rate (45.2%) than Seegene (53.7%), this likely reflects its selective detection of clinically significant infections rather than a lower detection capacity [

23,

24,

25].

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis further supported APTIMA’s superior discriminatory capacity, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.8804 compared to 0.8681 for Seegene (

p = 0.0563). While not statistically significant, this difference suggests that APTIMA may better differentiate between potentially pathogenic and benign infections based on molecular signatures [

19,

24]. However, it is important to clarify that as cytological or histological endpoints were not included, the findings pertain to analytical rather than clinical performance.

Differences in assay performance likely reflect underlying methodological distinctions. For instance, Abbott and Seegene both target the L1 region using real-time PCR but differ in approach, wherein, Abbott employs TaqMan hydrolysis probes to detect 14 HR-HPV types, while Seegene uses multiplex PCR with Dual Priming Oligonucleotide (DPO) primers and tagging oligonucleotide cleavage and extension (TOCE) technology to simultaneously genotype 28 HPV types [

8,

10]. In contrast, APTIMA targets E6/E7 mRNA transcripts, markers of viral oncogenic activity, using transcription-mediated amplification (TMA). These transcripts are typically upregulated in persistent infections, making mRNA detection a more biologically relevant approach for identifying infections with transformation potential [

10,

22].

This fundamental difference in biological targets complicates direct assay comparison. Nonetheless, comparing mRNA- and DNA-based assays remains relevant when assessing their suitability for screening, where both analytical characteristics and clinical implications must be carefully considered [

10,

11,

21]. In the context of this study, APTIMA’s performance supports its potential role in programmes aiming to prioritize the detection of persistent, high-risk infections over transient colonization, an approach that aligns with the overarching theme of improving strategies for detecting persistent HPV infections.

The genotype distribution derived from Seegene’s Allplex HPV28 assay was dominated by HPV16, followed by HPV58, 66, 35, and 18, mirroring previously reported data in South African populations [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The prominence of non-vaccine types such as HPV58 and HPV35 highlights the need for continued local genotype surveillance to inform future vaccine updates and screening strategies. Based on the distribution observed in this cohort, the 9-valent vaccine would have covered 73.0% of HR-HPV infections, compared to 41.0% and 36.2% coverage from the quadrivalent and bivalent vaccines, respectively. These findings support calls for broader-valency vaccine strategies, especially in high-burden settings where local HPV type prevalence diverges from global patterns. Additionally, WHO guidance recommends screening platforms capable of genotyping, as genotype-specific persistence is associated with differential risk for cervical precancer and can inform risk-based management pathways [

20].

Associations were observed between HPV positivity and socio-demographic variables, specifically employment and marital status (

p < 0.001), with higher prevalence among unemployed and single women. These findings align with regional studies linking socio-economic vulnerability to increased HPV acquisition and persistence [

30,

31]. In contrast, no significant associations were observed with age, ethnicity, province, or residence (urban vs rural). The absence of age-specific trends may reflect the clinical context of this cohort, that is, women already seeking care and presumed sexually active, resulting in high prevalence across age groups. This observation could obscure age-specific patterns typically observed in general populations [

32,

33], thus, supporting recent suggestions that age-based screening thresholds may need adaptation based on local epidemiological data [

21].

Collectively, these findings emphasize the importance of assay specificity in screening programmes, particularly in high-prevalence settings. While DNA-based assays offer broader genotyping for surveillance, mRNA-based tests like APTIMA enhance clinical relevance by detecting viral oncogene expression associated with transformation. This approach aligns with WHO recommendations to transition to HPV-based screening and highlights the value of biologically informed, operationally feasible tools in improving programmatic outcomes [

20]. By selectively identifying persistent infections, mRNA platforms contribute meaningfully to evolving strategies aimed at enhancing the predictive value of cervical screening.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. While the sample size was adequate for assay comparison, it may not be representative of the broader South African population, limiting generalizability. The geographic focus may also not reflect regional variations in HPV prevalence or genotype distribution. The cross-sectional design restricts assessment of infection persistence or progression, and the absence of histological endpoints (e.g., CIN2/3 lesions) limits interpretation of the assays’ clinical accuracy. Additionally, cost-effectiveness was not evaluated, an important consideration for implementation in resource-limited settings. Despite these limitations, the study provides key insights into the comparative performance of DNA- and mRNA-based assays and contributes valuable data on genotype prevalence among South African women.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that mRNA-based HPV testing, exemplified by the APTIMA assay, offers superior specificity and comparable sensitivity to DNA-based assays, supporting its clinical utility in cervical cancer screening, particularly in high-burden, resource-limited settings. The findings also show a genotype distribution dominated by HPV16, with notable prevalence of non-vaccine types such as HPV58 and HPV35, reinforcing the need for ongoing surveillance and broader-valency vaccine strategies. While limited by the absence of histological endpoints and longitudinal data, this study emphasizes the importance of aligning screening tools with epidemiologic realities to optimize cervical cancer prevention efforts in South Africa and similar contexts. These findings support WHO’s recommendation to transition to HPV-based molecular screening and underscore the potential programmatic value of mRNA assays in resource-constrained settings. Together, these insights inform the selection of screening tools that are both clinically effective and contextually appropriate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Varsetile Nkwinika and Ramokone Lebelo; Data curation, Varsetile Nkwinika and Ramokone Lebelo; Formal analysis, Varsetile Nkwinika; Funding acquisition, Ramokone Lebelo; Investigation, Varsetile Nkwinika and Kelvin Amissah; Methodology, Varsetile Nkwinika and Ramokone Lebelo; Project administration, Varsetile Nkwinika and Ramokone Lebelo; Resources, Ramokone Lebelo; Supervision, Jonny Rakgole, Moshawa Khaba, Cliff Magwira and Ramokone Lebelo; Validation, Ramokone Lebelo; Visualization, Varsetile Nkwinika; Writing – original draft, Varsetile Nkwinika; Writing – review & editing, Kelvin Amissah, Jonny Rakgole, Moshawa Khaba, Cliff Magwira and Ramokone Lebelo.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) Research Trust (GRANT004_94740), and Flemish Government: Flemish Interuniversity Council (VLIR-IUC) (VLIR-UOS ZIUS2015AP021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University (Ref: SMUREC/M/317/2022:PG).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study through the overarching study (Ref: SMUREC/P/75/2016:IR).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the women who participated in the study and the healthcare providers at gynaecology clinics (Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital) who assisted with recruitment and collection of the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| CIN |

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DPO |

Dual Priming Oligonucleotide |

| E6/E7 |

Early Proteins 6 and 7 (HPV oncogenes) |

| HPV |

Human Papillomavirus |

| HR-HPV |

High-Risk Human Papillomavirus |

| LBC |

Liquid-Based Cytology |

| LR-HPV |

Low-Risk Human Papillomavirus |

| mRNA |

Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| TMA |

Transcription-mediated amplification |

| TOCE |

Tagging oligonucleotide cleavage and extension |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- De Vuyst, H.; Alemany, L.; Lacey, C.; Chibwesha, C.J.; Sahasrabuddhe, V.; Banura, C.; Denny, L.; Parham, G.P. The burden of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in sub-saharan Africa. Vaccine. 2013, 31, F32–F46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedell, S.L.; Goldstein, L.S.; Goldstein, A.R.; Goldstein, A.T. Cervical Cancer Screening: Past, Present, and Future. Sex Med Rev. 2020, 8, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, G.; Dillner, J.; Elfström, K.M.; Tunesi, S.; Snijders, P.J.; Arbyn, M.; Kitchener, H.; Segnan, N.; Gilham, C.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; Berkhof, J.; Peto, J.; Meijer, C.J.; International HPV Screening Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014, 383, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.; Kostiuk, M.; Biron, V.L. Molecular Detection Methods in HPV-Related Cancers. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 864820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucksom, P.G.; Sherpa, M.L.; Pradhan, A.; Lal, S.; Gupta, C. Advances in HPV Screening Tests for Cervical Cancer-A Review. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2022, 72, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnam, S.; Coutlee, F.; Fontaine, D.; Bentley, J.; Escott, N.; Ghatage, P.; Gadag, V.; Holloway, G.; Bartellas, E.; Kum, N.; Giede, C.; Lear, A. Aptima HPV E6/E7 mRNA test is as sensitive as Hybrid Capture 2 Assay but more specific at detecting cervical precancer and cancer. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heideman, D.A.; Hesselink, A.T.; van Kemenade, F.J.; Iftner, T.; Berkhof, J.; Topal, F.; Agard, D.; Meijer, C.J.; Snijders, P.J. The Aptima HPV assay fulfills the cross-sectional clinical and reproducibility criteria of international guidelines for human papillomavirus test requirements for cervical screening. J Clin Microbiol. 2013, 51, 3653–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.; Verberckmoes, B.; Devolder, J.; Vermandere, H.; Degomme, O.; Guimarães, Y.M.; Godoy, L.R.; Ambrosino, E.; Cools, P.; Padalko, E. Comparison between the Roche Cobas 4800 Human Papillomavirus (HPV), Abbott RealTime High-Risk HPV, Seegene Anyplex II HPV28, and Novel Seegene Allplex HPV28 Assays for High-Risk HPV Detection and Genotyping in Mocked Self-Samples. Microbiol Spectr. 2023, 11, e0008123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevolo, M.; Vocaturo, A.; Caraceni, D.; French, D.; Rosini, S.; Zappacosta, R.; Terrenato, I.; Ciccocioppo, L.; Frega, A.; Giorgi Rossi, P. Sensitivity, specificity, and clinical value of human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 mRNA assay as a triage test for cervical cytology and HPV DNA test. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49, 2643–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Simon, M.; Peeters, E.; Xu, L.; Meijer, C.J.L.M.; Berkhof, J.; Cuschieri, K.; Bonde, J.; Ostrbenk Vanlencak, A.; Zhao, F.H.; Rezhake, R.; Gultekin, M.; Dillner, J.; de Sanjosé, S.; Canfell, K.; Hillemanns, P.; Almonte, M.; Wentzensen, N.; Poljak, M. 2020 list of human papillomavirus assays suitable for primary cervical cancer screening. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021, 27, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockter, J.; Schroder, A.; Hill, C.; Guzenski, L.; Monsonego, J.; Giachetti, C. Clinical performance of the APTIMA HPV Assay for the detection of high-risk HPV and high-grade cervical lesions. J Clin Virol. 2009, 45 (Suppl 1), S55–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarankiewicz, N.; Zielińska, M.; Kosz, K.; Kuchnicka, A.; Ciseł, B. High-risk HPV test in cervical cancer prevention – present and future. J Pre Clin Clin Res. 2020, 14, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.C.; Denny, L.; Wang, C.; Tsai, W.Y.; Wright TCJr Kuhn, L. Distribution of high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes among HIV-negative women with and without cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in South Africa. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e44332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, R.; Cuzick, J.; Hunt, W.C.; McDonald, R.M.; Wheeler, C.M.; New Mexico HPV Pap Registry Steering Committee. Role of HPV Genotype, Multiple Infections, and Viral Load on the Risk of High-Grade Cervical Neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019, 28, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, J.O.; Ofodile, C.A.; Adeleke, O.K.; Obioma, O. Prevalence of high-risk HPV genotypes in sub-Saharan Africa according to HIV status: a 20-year systematic review. Epidemiol Health. 2021, 43, e2021039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbulawa, Z.Z.A.; Phohlo, K.; Garcia-Jardon, M.; Williamson, A.L.; Businge, C.B. High human papillomavirus (HPV)-35 prevalence among South African women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia warrants attention. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0264498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mafi, S.; Theuillon, F.; Meyer, S.; Woillard, J.B.; Dupont, M.; Rogez, S.; Alain, S.; Hantz, S. Comparative evaluation of Allplex HPV28 and Anyplex II HPV28 assays for high-risk HPV genotyping in cervical samples. PLoS One. 2025, 20, e0320978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulmala, S.M.; Syrjänen, S.; Shabalova, I.; Petrovichev, N.; Kozachenko, V.; Podistov, J.; Ivanchenko, O.; Zakharenko, S.; Nerovjna, R.; Kljukina, L.; Branovskaja, M.; Grunberga, V.; Juschenko, A.; Tosi, P.; Santopietro, R.; Syrjänen, K. Human papillomavirus testing with the hybrid capture 2 assay and PCR as screening tools. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42, 2470–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, A.T.; Valls, J.; Baena, A.; Rojas, F.D.; Ramírez, K.; Álvarez, R.; Cristaldo, C.; Henríquez, O.; Moreno, A.; Reynaga, D.C.; Palma, H.G.; Robinson, I.; Hernández, D.C.; Bardales, R.; Cardinal, L.; Salgado, Y.; Martínez, S.; González, E.; Guillén, D.; Fleider, L.; Tatti, S.; Villagra, V.; Venegas, G.; Cruz-Valdez, A.; Valencia, M.; Rodríguez, G.; Terán, C.; Picconi, M.A.; Ferrera, A.; Kasamatsu, E.; Mendoza, L.; Calderon, A.; Luciani, S.; Broutet, N.; Darragh, T.; Almonte, M.; Herrero, R.; ESTAMPA Study Group. Performance of cervical cytology and HPV testing for primary cervical cancer screening in Latin America: an analysis within the ESTAMPA study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023, 26, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention [Internet], 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 8 May 2021; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572317/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Sørbye, S.W.; Falang, B.M.; Botha, M.H.; Snyman, L.C.; van der Merwe, H.; Visser, C.; Richter, K.; Dreyer, G. Enhancing Cervical Cancer Prevention in South African Women: Primary HPV mRNA Screening with Different Genotype Combinations. Cancers. 2023, 15, 5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Simon, M.; de Sanjosé, S.; Clarke, M.A.; Poljak, M.; Rezhake, R.; Berkhof, J.; Nyaga, V.; Gultekin, M.; Canfell, K.; Wentzensen, N. Accuracy and effectiveness of HPV mRNA testing in cervical cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 950–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijkaart, D.C.; Heideman, D.A.; Coupe, V.M.; Brink, A.A.; Verheijen, R.H.; Skomedal, H.; Karlsen, F.; Morland, E.; Snijders, P.J.; Meijer, C.J. High-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) E6/E7 mRNA testing by PreTect HPV-Proofer for detection of cervical high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer among hrHPV DNA-positive women with normal cytology. J Clin Microbiol. 2012, 50, 2390–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiiti, T.A.; Mashishi, T.L.; Nkwinika, V.V.; Benoy, I.; Selabe, S.G.; Bogers, J.; Lebelo, R.L. High-risk human papillomavirus detection in self-collected vaginal samples compared with healthcare worker collected cervical samples among women attending gynecology clinics at a tertiary hospital in Pretoria, South Africa. Virol J. 2021, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbie, A.; Maier, M.; Amare, B.; Misgan, E.; Nibret, E.; Biadglegne, F.; Liebert, U.G.; Minas, T.Z.; Yenesew, M.A.; Nigatu, D.; Mersha, T.B.; Enquobahrie, D.A.; Woldeamanuel, Y.; Abebe, T. HPV E6 and E7 mRNA Test for the Detection of High-Grade Cervical Lesions. JAMA Netw Open. 2025, 8, e2459698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiiti, T.A.; Selabe, S.G.; Bogers, J.; Lebelo, R.L. High prevalence of and factors associated with human papillomavirus infection among women attending a tertiary hospital in Gauteng Province, South Africa. BMC Cancer. 2022, 22, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbulawa, Z.Z.; Marais, D.J.; Johnson, L.F.; Coetzee, D.; Williamson, A.L. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus on the natural history of human papillomavirus genital infection in South African men and women. J Infect Dis. 2012, 206, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, L.; Adewole, I.; Anorlu, R.; Dreyer, G.; Moodley, M.; Smith, T.; Snyman, L.; Wiredu, E.; Molijn, A.; Quint, W.; Ramakrishnan, G.; Schmidt, J. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in invasive cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Cancer. 2014, 134, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikhotso, R.R.; Mitchell, E.M.; Wilson, D.T.; Doede, A.; Matume, N.D.; Bessong, P.O. Prevalence and distribution of selected cervical human papillomavirus types in HIV infected and HIV uninfected women in South Africa, 1989-2021: A narrative review. S Afr J Infect Dis. 2022, 37, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah-Dacosta, E.; Blose, N.; Nkwinika, V.V.; Chepkurui, V. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in South Africa: Programmatic Challenges and Opportunities for Integration With Other Adolescent Health Services? Front Public Health 2022, 10, 799984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbulawa, Z.Z.A.; van Schalkwyk, C.; Hu, N.C.; Meiring, T.L.; Barnabas, S.; Dabee, S.; Jaspan, H.; Kriek, J.M.; Jaumdally, S.Z.; Muller, E.; Bekker, L.G.; Lewis, D.A.; Dietrich, J.; Gray, G.; Passmore, J.S.; Williamson, A.L. High human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence in South African adolescents and young women encourages expanded HPV vaccination campaigns. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0190166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, K.; Becker, P.; Horton, A.; Dreyer, G. Age-specific prevalence of cervical human papillomavirus infection and cytological abnormalities in women in Gauteng Province, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2013, 103, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbulawa, Z.Z.; Coetzee, D.; Williamson, A.L. Human papillomavirus prevalence in South African women and men according to age and human immunodeficiency virus status. BMC Infect Dis. 2015, 15, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).