1. Introduction

The temporary economy emerged as a key issue in the review of modern employment practices. Taylor et al. (2017), identified the temporary economy as comprising platform, on-site delivery, physical and, remote delivery, and exchange work. Huws et al. (2016), estimated that approximately 70 million workers worldwide are registered on online labor platforms that facilitate remote work. Heeks (2017) reported that the index of online labor platform usage is increasing at a rate of 26% per year (Kässi & Lehdonvirta 2016). However, despite being employed in at temporary economy, there are concerns about its impact on future work. Piecework creates insecurity and reduces the standard employment relationship, which should be carefully considered when developing future economic policies and human resource management in at temporary economy (Wood et al. 2019). Most previous studies have focused on permanent employees; however researchers are now increasingly interested in temporary work (Oliveira et al. 2021). Policies that address employee attitudes and behaviors focus on flexibility and developing skills that are in line with current and future changes enable flexible work in today's business and social worlds. (Brauner et al., Research in Thailand has found a growing trend of temporary work, with a 170% increase in temporary job applicants, and digital graphic work is a major factor. The increase in online business work, according to research by the National Council for Higher Education, Science, Research, and Innovation Policy in 2021. Changes in the free market economy in Thailand have affected the trend of temporary work, especially part-time work, causing high levels of stress and job uncertainty, which affect employees' mental and physical health. Learning about employee well-being can help organizations manage and promote employees, reduce emotional exhaustion, and increase their mental energy and self-esteem. This, in turn, affects well-being (Gabriel et al. 2020). Other research also suggests that it is important to create an environment that protects employees’ mental and emotional well-being (Montgomery et al. 2022), leading to long-term job performance and success (Alvarez-Torres & Schiuma 2022; Li et al. 2021).

Work flexibility affects employees’ well-being by enabling them to meet their own mental and physical health needs and improve their quality of life, both at work and outside of work. Work flexibility is a key factor in today’s workplace that promotes innovative work behaviors, which are important for organizations that want to lead and grow in today’s competitive business environment (Afrin et al. 2022; Jain 2022; Muhamad et al. 2023). Work techniques and support are also important factors in promoting creative work behaviors (Koroglu & Ozmen 2021). Innovative work behaviors affect job performance by enhancing employees’ ability to solve problems and develop innovation in their work. It makes job performance more creative and effective according to the needs of the organization (Saridakis et al. 2020). Job performance reflects an employee’s ability to achieve organizational goals (Ángeles López-Cabarcos et al. 2022; Deng et al. 2022; Wibowo et al. 2022).

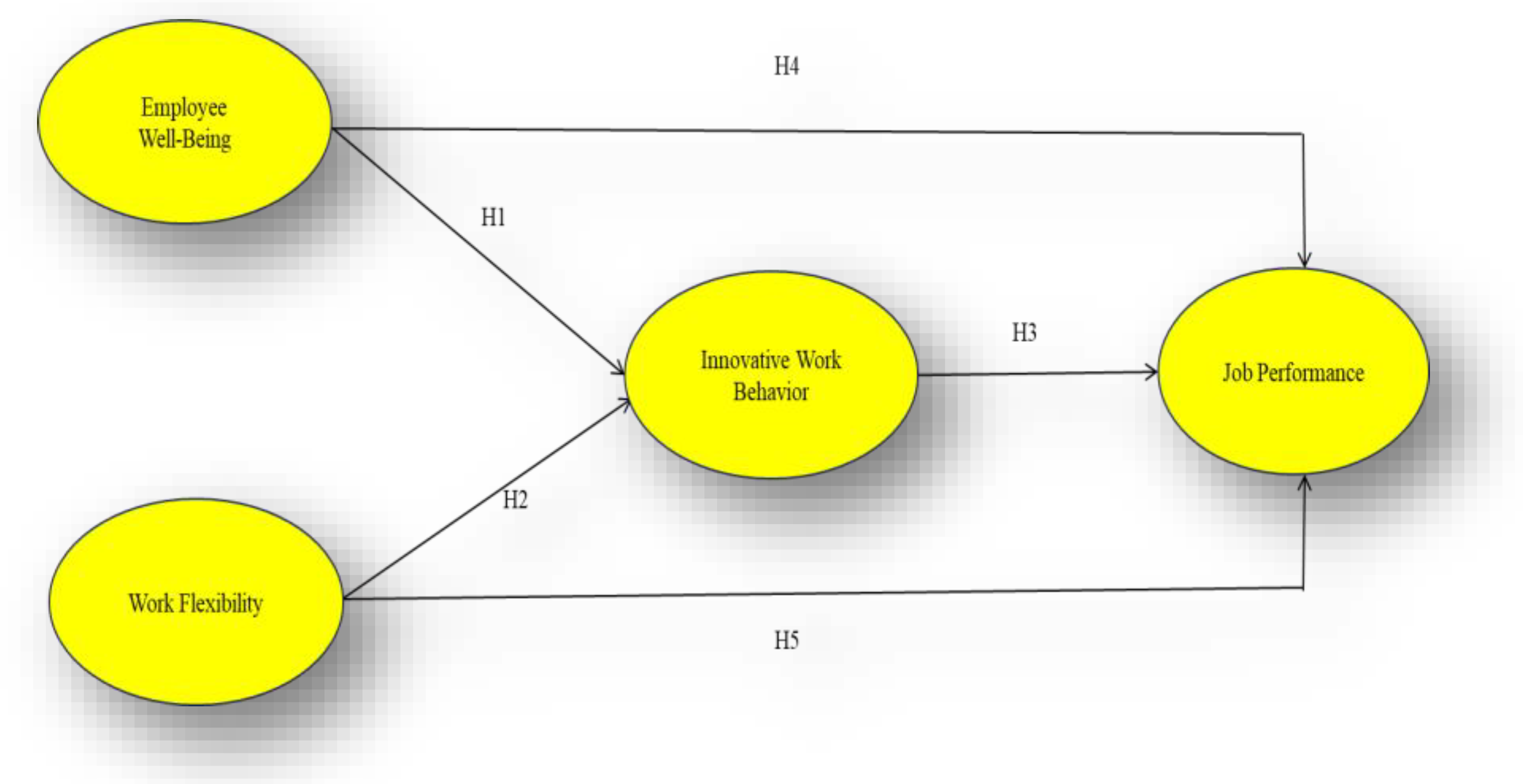

A review of the literature on employee well-being, work flexibility, and innovative work behavior, found that job performance is directly affected by employee well-being and work flexibility, which, in turn, affects innovative behavior in the organization. Blau’s (1964) social exchange theory, describes the relationship between employees and organizations based on mutual benefit exchange. While substantial research has examined employee well-being (EWB), work flexibility (WF), and innovative work behavior (IWB), most studies have focused on permanent employees and have neglected the role of temporary employees in the digital economy. Furthermore, limited research has addressed these variables within Thailand’s cultural context, where trust and personal relationships significantly influence workplace dynamics. The differentiation between permanent and temporary employees in terms of factors affecting IWB in digital business environments remains underexplored. Additionally, the application of Social Exchange Theory (SET) explains the interplay of EWB and WF with job performance (JP) and IWB in diverse employment contexts. This study bridges these gaps by analyzing the effects of EWB and WF on IWB and JP among permanent and temporary employees in the digital sector, offering insights for effective workforce management.

2. Literature Review

Theoretical Background

Social Exchange Theory (SET), which originated in the 1920s, has significantly influenced various disciplines, including social psychology (Homans 1958), and sociology (Blau 1964). This theory explains interpersonal behavior through the exchange of resources and expectations of returns. Homans(1969), further developed SET in the context of stock market studies, highlighting behavior, commitment, trust, fairness, and coalition formation. More recently, SET has been expanded to incorporate the role of emotions in social exchanges, both in controlled environments and real-world settings. From an economic perspective, (Zychlinski et al. 2021), emphasized the relevance of SET to contemporary business operations, with Cropanzano et al.(2017), noting that social exchanges are essential not only within organizations but also in daily life, such as in family and peer relationships. Prior research, including studies by Kmieciak (2020), Koroglu and Ozmen (2021), Liu et al.(2023), and Ridwan et al.(2020), has applied SET to examine employee behavior and job performance, particularly in relation to innovative work behavior. This study posits that when employees perceive a positive psychological and social environment and are supported by flexible work arrangements, they are more likely to exhibit innovative behavior, ultimately leading to optimal job performance.

Employee Well-Being and Innovative Work Behavior

Interpersonal relationships within organizations enhance employee well-being by fostering trust and a positive work climate, which, in turn, encourages innovative behavior. Nazir et al. (2019) emphasized that employee well-being promotes innovative work behavior when supported by organizational cultures that encourage information sharing, reward systems, and social networking. Rasool et al.(2021), found that organizational support and well-being reduce negative work environments, whereas self-efficacy boosts both well-being and innovation performance(Singh et al. 2019). Despite growing interest in this area, Afsar et al.(2020), and Nguyen et al.(2019) noted limited research on enhancing overall employee motivation and well-being. Miao and Cao(2019), identified a positive link between well-being and innovative behavior, while AlSuwaidi et al.(2021), highlighted that well-being also motivates pro-environmental actions. Effective management strategies, such as promoting psychological capabilities (Mishra et al. 2019), providing job flexibility and safety during crises, such as COVID-19 (Azizi et al. 2021), and fostering supportive leadership (Cai et al. 2018), are essential for driving innovative behavior and job performance. Kim and Park (2017), further stress the role of employee engagement in enhancing performance. This study proposes that Social Exchange Theory (SET) explains the relationship between employee well-being and innovative work behavior. Therefore, this study aimed to explore this relationship to develop policies and strategies that promote well-being and stimulate innovation in the workplace. Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypotheses.

H1: Employee well-being has a positive influence on innovative work behavior.

Work Flexibility and Innovative Work Behavior

Work flexibility refers to the balance between work and personal life, including flexible working hours, location, and communication methods tailored to individual needs. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced many organizations to restructure their arrangements. Allowing employees to choose their work style, location, and communication technologies can alleviate these challenges, because flexible working supports better adaptability. Telework, when supported by proper facilities and effective communication systems, is a viable alternative (Aidla et al. 2022). Work flexibility is closely linked to innovative work behavior, with psychological empowerment and knowledge sharing serving as key enablers(Wen et al. 2021). Ethical leadership and self-esteem positively influence innovation(Yasir et al. 2021). Rafique et al. (2022). found that leader-member exchange (LMX) and schedule flexibility significantly impact employee empowerment and innovative behavior. Similarly, knowledge sharing plays a vital role in fostering innovation(Anser et al. 2020). Chua et al. (2022), highlighted the importance of open-plan workspace designs and a robust IT infrastructure for adopting flexible work arrangements. In addition, smart technologies, digital applications, and modern IT systems can enhance workplace management and operations. Aura and Desiana (2023), emphasized that flexible working styles, where employees manage their own time and workplace, reflect adaptive human resource practices. Autonomy promotes psychological empowerment and enhances innovation performance. Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypotheses.

H2: Work flexibility has a positive influence on innovative work behavior.

3. Methodology

Measurement

The researchers reviewed the literature to determine the study’s components, working definitions, and variable structures. A questionnaire, comprising four sections covering key variables, was developed. The first measures employee well-being and was, adapted from Kuriakose and Sreejesh (2023), Jaiswal et al.(2022), and Pradhan and Hati (2019). The second section assessed work flexibility, adapted from Chatterjee et al. (2022), Hartner-Tiefenthaler et al.(2022), and Aura and Desiana(2023). The third section focuses on innovative work behavior, adapted from Parnitvitidkun et al. (2024) (2024).. The final section evaluates job performance, as adapted from Sanlioz et al. (2023), Santos et al.(2018), and Pachec et al.(2023). A 5-point Likert scale was used (1 = least, 5 = most) (Bell et al. 2022), where higher scores indicate greater awareness and lower scores indicate less awareness. Lower scores indicate less awareness. The data collection questionnaire was approved by the Human Research Ethics Exemption Review, (Code HE673232), of the Human Research Ethics Committee of Khon Kaen University.

Data Coll ection

This study was conducted in Thailand with a sample of 201 full-time employees working in digital business system development (Digital Economy 2023). Participants were male or female, aged 20–60 years, with at least two years of work experience, ensuring that they could provide relevant insights into employee well-being, work flexibility, innovative work behavior, and performance (Garg & Dhar 2017). The questionnaire was distributed online, using a web-based platform. Additionally, gig workers from the IT Support Thailand public Facebook group, who occasionally worked in digital business system development, were included. As the exact population size was unknown, Cochran's (1977) formula was applied, suggesting a sample size of 384 at a 95% confidence level and a 5% error margin. Convenience sampling was also conducted. However, only 199 valid responses were received, likely because of concerns about the data security and privacy associated with online surveys. Despite this, the response rate exceeded 50%, which Hoonakker and Carayon (2009), considered acceptable for online surveys and sufficient for data analyses. Therefore, the final sample size was deemed appropriate. The relevant details are presented in .

Methodology

The analysis was conducted in two phases. First, multiple group Structural Equation Modeling (MG-SEM) using GSCA Pro 1.2.1, a free licensed software, developed by Hwang and available for downloading from the developer's official website, examined the variables and generated factor scores. (Hwang et al. 2023a; Manosuthi et al. 2021). This approach improves validity by addressing moderator research gaps (Lee et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2019), and convergent validity was confirmed with factor loadings > 0.7 (strong) or > 0.6 (acceptable), average variance extracted > 0.50, and CR >0.70 (Hair et al. 2020). Discriminant validity was assessed using the HTMT (<0.85) (Fornell & Larcker 1981). For the FIT model, the acceptable when FIT and the ideal value should be close to 1(Hwang et al. 2023b), SRMR < 0.08, and GFI > 0.9 (Benitez et al. 2020; Hair et al. 2020; Manosuthi et al. 2021). For NCA, it was analyzed according to Dul (2015), is having if p < 0.05 (Manosuthi et al. 2021). This method is gaining popularity in MG-SEM research.

Table 1.

Population Demographics.

Table 1.

Population Demographics.

Respondent profile

|

Category |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Gender |

Male |

206 |

51.50 |

| |

Female |

194 |

48.50 |

| Age |

> 25 years |

35 |

8.75 |

| |

25 – 30 years |

112 |

28.00 |

| |

31-40 years |

133 |

33.25 |

| |

41-50 years |

85 |

21.25 |

| |

51-60 years |

27 |

6.75 |

| |

< 60 years |

8 |

2.00 |

| Education level |

Below bachelor’s degree |

37 |

9.25 |

| |

Bachelor's degree |

256 |

64.00 |

| |

Above bachelor’s degree |

107 |

26.75 |

| Nature of work |

Digital services |

108 |

27.00 |

| |

Software and software services |

194 |

48.50 |

| |

Digital content |

63 |

15.75 |

| |

Other (please specify) |

35 |

8.75 |

| Employment type |

Full-time |

201 |

50.25 |

| |

Gig worker |

199 |

49.75 |

| Average monthly Income |

> 30,000 THB |

118 |

29.50 |

| |

30,000 – 40,000 THB |

101 |

25.25 |

| |

40,001 – 50,000 THB |

88 |

22.00 |

| |

50,001 – 60,000 THB |

52 |

13.00 |

| |

Over 60,000 THB |

41 |

10.25 |

| Work experience in the digital business Sector |

1 - 2 years |

128 |

32.00 |

| |

3 - 4 years |

148 |

37.00 |

| |

< 5 years |

124 |

31.00 |

4. Results

The analysis was conducted in three phases. First, (MG-SEM) was used to examine all variables and generate component scores (Manosuthi et al. 2021). In the second phase, these scores were analyzed using NCA to identify essential variables (Richter et al. 2020). To enhance external validity, the component scores were divided into high and low groups (one SD above and below the mean) for each variable: employee well-being, work flexibility, innovative work behavior, and job performance, following Aiken and West's (1991), guidelines. This approach addresses previously overlooked research gaps (Lee et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2019). Finally, the interaction effects among all the variables were assessed using component scores. The proposed research framework was evaluated using a fully informed estimator and integrated generalized structural component analysis. Convergent validity was used to evaluate the average variance extracted (AVE) of the EWB, WF, IWB, and JP variables for both permanent and temporary employees, with an AVE value of at least 0.50. However, an AVE value of 0.40 was considered acceptable, with the CR being more than the acceptable level of adequate reliability(0.6) considered(Lam 2012; Maruf et al. 2021), as convergent validity according to the criteria in MG-SEM (). In addition, to examine discriminant validity, this study adopted an advanced heterogeneous -univariate correlation ratio. This method is popular because it can estimate the relationship between latent variables without bias compared with the traditional method (Roemer et al. 2021). The results indicated that all values were lower than the recommended criterion (0.85), confirming the discriminant validity (Roemer et al. 2021). No significant conflicting issues were found, as all VIF values were less than 5 (Belsley et al. 2005). Additional measures were used in this study, as recommended by Hwang et al.(2023a). The results showed that the proposed model is suitable for theoretical data (FIT = 0.870, GFI = 0.951, SRMR = 0.088) (Benitez et al. 2020; Hair et al. 2020; Hwang et al. 2023b; Manosuthi et al. 2021).This met the criteria for the analysis, which focused on assessing the appropriateness of the GFI and SRMR. When N > 100, researchers may choose a GFI cutoff of 0.93 and an SRMR cutoff of 0.08. In this case, no one index is chosen over another, or a combination of indices is used instead of using each index separately. The recommended cutoff values of each index may be used separately to assess the fit of the model, that is, GFI ≥ 0.93 or SRMR ≤ 0.08, indicating acceptable fit (Cho et al. 2020). Therefore, the research model was reliable and valid. We then study the relationship between the research constructs. Multiple path coefficients showed significant and positive relationships between identified causes and desired outcomes (). The main concepts of full-time and gig workers are employee well-being, work flexibility, innovative work behaviors, and job performance. The results show a positive influence, as hypothesized H1, H2, and H3, whereas H4 and H5 show a negative relationship between the identified causes and desired outcomes.

In addition, we examined the relationships between employees' well-being, work flexibility, creative work behaviors, and work performance. Our results indicate that EWB and WF have significant effects on IWB, and IWB has a significant effect on JP, EWB and WF have no significant effects on JP, thus supporting H1, H2, and H3.

Table 2.

Verification of the Research Framework.

Table 2.

Verification of the Research Framework.

| Construct Indicator |

AVE |

CR |

wi

|

CIwi |

i

|

CIi

|

| EWB |

I consistently value your work. |

0.417 |

0.865 |

0.190 |

[0.1660,0.2232] |

0.715 |

[0.6470,0.7620] |

| |

I work Job performance inspires. |

|

|

0.172 |

[0.1477,0.1928] |

0.645 |

[0.5500,0.7180] |

| |

I am enthusiastic about developing skills. |

|

|

0.176 |

[0.1548,0.2030] |

0.662 |

[0.5860,0.7260] |

| |

I am involved in teamwork with colleagues to achieve goals. |

|

|

0.166 |

[0.1488,0.1897] |

0.625 |

[0.5620,0.7030] |

| |

I have a way of building and maintaining good social relationships with people around. |

|

|

0.142 |

[0.1186,0.1577] |

0.532 |

[0.4040,0.6360] |

| |

I am able to adapt to changes in life on a daily basis. |

|

|

0.167 |

[0.1501,0.1870] |

0.629 |

[0.5010,0.7070] |

| |

I feel confident in using your expertise and experience in work. |

|

|

0.184 |

[0.1653,0.2150] |

0.692 |

[0.6170,0.7700] |

| |

I feel happy at work. |

|

|

0.172 |

[0.1517,0.2041] |

0.647 |

[0.5830,0.6970] |

| |

I am able to manage and control emotional reactions. |

|

|

0.174 |

[0.1580,0.1912] |

0.652 |

[0.5630,0.7440] |

| WF |

I can work whenever want. |

0.469 |

0.812 |

0.331 |

[0.3009,0.3591] |

0.777 |

[0.7130,0.8380] |

| |

I can manage working hours to help be more productive. |

|

|

0.286 |

[0.2615,0.3072] |

0.672 |

[0.6060,0.7440] |

| |

I can set own working style. |

|

|

0.320 |

[0.2940,0.3461] |

0.751 |

[0.6840,0.8140] |

| |

I can choose own workplace. |

|

|

0.305 |

[0.2754,0.3412] |

0.716 |

[0.6560,0.7980] |

| |

I can use technology to communicate effectively. |

|

|

0.198 |

[0.1624,0.2383] |

0.464 |

[0.3590,0.5810] |

| IWB |

I find new ideas for your work to solve problems for I service recipients |

0.454 |

0.892 |

0.155 |

[0.1405,0.1697] |

0.703 |

[0.6520,0.7560] |

| |

I studied the feasibility of using new methods or solutions to benefit work. |

|

|

0.155 |

[0.1396,0.1713] |

0.701 |

[0.6480,0.7640] |

| |

I can analyze the real problems of your work. |

|

|

0.131 |

[0.1174,0.1479] |

0.596 |

[0.5150,0.6760] |

| |

I meet and discuss with colleagues to exchange new ideas for your work. |

|

|

0.142 |

[0.1310,0.1571] |

0.642 |

[0.5740,0.7210] |

| |

I am proactive in learning and seeking up-to-date knowledge. |

|

|

0.147 |

[0.1310,0.1635] |

0.665 |

[0.5860,0.7620] |

| |

I collect information or opinions from service recipients and related persons. |

|

|

0.151 |

[0.1366,0.1673] |

0.686 |

[0.6220,0.7420] |

| |

I have new ideas for providing services. |

|

|

0.155 |

[0.1411,0.1771] |

0.702 |

[0.6410,0.7640] |

| |

I evaluate the results after implementing new methods or new problem-solving methods |

|

|

0.156 |

[0.1424,0.1723] |

0.710 |

[0.6430,0.7680] |

| |

I apply new methods of work to solve unresolved problems. |

|

|

0.146 |

[0.1317,0.1642] |

0.661 |

[0.5960,0.7180] |

| |

I present or recommend to your colleagues to implement the new methods have created. |

|

|

0.146 |

[0.1322,0.1588] |

0.662 |

[0.5920,0.7300] |

| JP |

I complete the assigned tasks within the specified time frame. |

0.485 |

0.903 |

0.151 |

[0.1388,0.1624] |

0.732 |

[0.6480,0.8050] |

| |

I can efficiently perform the tasks specified in the job description. |

|

|

0.158 |

[0.1396,0.1763] |

0.766 |

[0.7100,0.8200] |

| |

I can perform the tasks in accordance with the assigned position, according to standards and with quality. |

|

|

0.145 |

[0.1308,0.1660] |

0.703 |

[0.6450,0.7720] |

| |

I work plays an important role in the success of the project or assigned task. |

|

|

0.146 |

[0.1322,0.1629] |

0.706 |

[0.6180,0.7780] |

| |

I can efficiently and successfully complete special assignments. |

|

|

0.152 |

[0.1369,0.1702] |

0.735 |

[0.6440,0.8110] |

| |

I can efficiently perform and achieve the set goals. |

|

|

0.149 |

[0.1355,0.1649] |

0.721 |

[0.6460,0.7850] |

| |

I have achieved the quality criteria set for work. |

|

|

0.159 |

[0.1411,0.1748] |

0.772 |

[0.6790,0.8330] |

| |

I have completed more work than the set target. |

|

|

0.105 |

[0.0935,0.1204] |

0.510 |

[0.4160,0.6220] |

| |

I have achieved higher quality work than the set standard. |

|

|

0.116 |

[0.1028,0.1282] |

0.563 |

[0.4680,0.6400] |

| |

I have achieved the results of work that are responsible for. |

|

|

0.146 |

[0.1339,0.1624] |

0.708 |

[0.6370,0.7830] |

Table 3.

Multiple Group SEM Analysis and Hypothesis Testing.

Table 3.

Multiple Group SEM Analysis and Hypothesis Testing.

| Relationship |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

95%CI (L, U) |

Result |

| |

G1 |

G2 |

G1 |

G2 |

G1 |

G2 |

|

| H1 : EWB -> IWB |

0.716*

|

0.543*

|

0.083*

|

0.089*

|

[0.534,0.832] |

[0.359,0.699] |

Supported |

| H2 : WF -> IWB |

0.159*

|

0.294*

|

0.080*

|

0.094*

|

[0.042,0.355] |

[0.145,0.495] |

Supported |

| H3 : IWB - > JP |

0.715*

|

0.751*

|

0.202*

|

0.170*

|

[0.203,1.006] |

[0.327,1.051] |

Supported |

| H4 : EWB -> JP |

0.135 |

0.065 |

0.205 |

0.199 |

[-0.175,0.670] |

[-0.310,0.450] |

Not Supported |

| H5 : WF- > JP |

-0.048 |

0.003 |

0.087 |

0.144 |

[-0.233,0.116] |

[-0.180,0.264] |

Not Supported |

5. Discussion

A study of full-time gig workers in digital businesses supports three key hypotheses. H1 confirms that employee well-being positively influences innovative work behavior (β = 0.715, 0.544). Full-time workers benefit from job security and career growth, fostering motivation and commitment, whereas gig workers leverage flexibility for creative problem solving. Despite these differences, both groups rely on organizational support and leadership to enhance well-being and innovation (Nazir et al. 2019; Rasool et al. 2021; Singh et al. 2020). H2 reveals that work flexibility positively impacts innovative work behavior (β = 0.156, 0.298). Although full-time workers enjoy stability, their limited flexibility may hinder creativity. By contrast, gig workers benefit from flexible schedules, adapt quickly, and generate new ideas. However, job insecurity can influence morale among gig workers, contrasting with the relatively secure environment of full-time employees. Organizations should balance stability and flexibility to support innovation (Anser et al. 2020; Wen et al. 2021; Yasir et al. 2021). H3 establishes that innovative work behavior enhances job performance (β = 0.740, 0.765). Full-time workers thrive in stability and development, whereas gig workers gain diverse experiences but struggle with job insecurity. Despite these contrasts, both groups ultimately depend on innovation as a critical driver of performance. Organizations must support both groups to drive innovation and long-term performance (Alikaj et al. 2020; Shanker et al. 2017). However, H4 found that employee well-being did not significantly affect job performance. Full-time workers focus on achievement and undervalue well-being, whereas gig workers prioritize financial stability over health (Abdullah et al. 2021; Kosec et al. 2022). Similarly, H5 indicates that work flexibility does not significantly influence performance, especially in rigid organizational cultures. Employees may not perceive flexibility as beneficial because of management constraints, teamwork demands, or a lack of telework support and this perception can vary between full-time and gig workers depending on their work conditions (Irawan & Sari 2021; Taibah & Ho 2023). Overall, organizations must tailor strategies to support both full-time and gig workers, fostering a culture that balances well-being, flexibility, and innovation for sustainable job performance, while also recognizing the unique needs, strengths, and challenges of each group.

This study employs MG-SEM between employee well-being and work flexibility. The findings indicate that, while both factors are crucial for fostering creative work behavior and performance, they do not support a direct positive impact of well-being on job performance. However, employee well-being is essential for creative work behavior, which drives performance (Fakfare et al. 2024). Although work flexibility does not directly enhance job performance, it is a necessary condition for creativity, a key driver of high job performance. This finding underscores the need for a work culture that nurtures innovation. Ultimately, the study revealed that, without creative work behavior, high performance may not materialize, despite work flexibility and well-being. Flexibility fosters well-being. Notably, while flexibility fosters well-being and supports long-term performance in both groups, the mechanisms differ: full-time workers benefit more from structured support and career development, whereas gig workers depend on adaptability and diverse work experiences. Ultimately, organizations must embrace differentiated strategies that acknowledge these group-specific dynamics to sustain innovation and performance.

6. Conclusion

This study examines how organizations can better support employees by adapting strategies to different workforce groups. Permanent employees need job security, career growth, and strong benefits to stay engaged, while casual employees value flexibility, diverse work experiences, and support into managing job insecurity. To identify the key factors influencing employee performance, this study used Necessary Condition Analysis to determine the essential conditions for success. When organizations manage both permanent and casual employees under the same strategy, Multi-Group Structural Equation Modeling is applied alongside Necessary Condition Analysis for a more complete analysis. The findings reveal that organizations must meet specific conditions to achieve high performance. This study provides useful insights for individuals, businesses, and global research based on data from Thailand. Companies in the digital business sector can use these findings to improve their workplace well-being, increase job flexibility, and promote innovation, leading to sustainable growth and a competitive edge.

Theoretical contribution

This study contributes to the theoretical understanding of employee well-being, work flexibility, and innovative work behavior in digital businesses. It provides empirical support for the hypothesis that employee well-being positively influences innovative work behavior (H1), highlighting the critical role of well-being factors such as physical and mental health, a supportive work environment, and work-life balance. These findings align with those of previous studies, reinforcing the importance of fostering an organizational culture that prioritizes employee well-being to enhance creativity and innovation (Nazir et al. 2019; Rasool et al. 2021). Additionally, the study confirms that work flexibility positively impacts innovative work behavior (H2), demonstrating that flexibility in time and location can stimulate creativity, particularly among casual employees. This supports research by emphasizing the necessity of flexible work arrangements to foster creative thinking and problem-solving skills (Wen et al. 2021; Yasir et al. 2021). Furthermore, the study reveals that innovative work behavior significantly influences job performance (H3), with both permanent and casual employees benefiting from innovative practices. This finding aligns with those of other studies, underscoring the importance of promoting innovative behavior to enhance overall job performance (Alikaj et al. 2020). However, the study also found that employee well-being did not significantly influence job performance (H4), and work flexibility did not significantly influence work performance (H5), challenging the conventional wisdom that well-being and flexibility are directly correlated with performance. These insights suggest that while well-being and flexibility are crucial for fostering innovative work behavior, they do not directly translate to improved job performance without the mediation of creative behaviors (Shanker et al. 2017).

Practical Implications

The practical implications of this study are multifaceted and provide valuable insights for managers and policymakers in digital business. Organizations promoting employee well-being should invest in comprehensive well-being programs that address both physical and mental health, provide a supportive work environment, and promote work-life balance. This investment is essential for enhancing innovative work behavior, as demonstrated by the positive correlation between well-being and creativity. Employers should consider implementing wellness initiatives, offering mental health support, and creating a culture that values employee well-being. Given the positive impact of work flexibility on innovative behavior, organizations should explore flexible work arrangements, such as remote work options and flexible schedules. These arrangements can help casual employees leverage their adaptability and creativity while also providing permanent employees with the flexibility needed to stimulate innovative thinking. Organizations should develop policies that support flexible work practices and provide the necessary tools and resources for effective teleworking. Organizations should create an environment that encourages creativity and idea generation to enhance job performance through innovative work behavior. This can be achieved by providing opportunities for skill development, fostering open communication, and recognizing and rewarding innovative contributions. Leaders should focus on creating a supportive and inclusive culture that empowers employees to experiment with and be innovative.

Limitations and Future Studies

This study has several limitations. First, the study employed only quantitative methods, utilizing structural equation modeling for analysis. The lack of qualitative approaches limits the depth of insights that can be obtained. Incorporating qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, could provide a more nuanced understanding and actionable insights into the factors influencing employee well-being, work flexibility, and innovative behavior. For example, employing fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) (Manosuthi et al. 2021). It could be advantageous, as it provides both causal and non-causal explanations, enhancing theory development and testing. Second, while the study identifies significant relationships between employee well-being, work flexibility, and innovative work behavior, it does not delve deeply into the specific aspects of these variables. A more detailed examination of elements, such as types of flexible work arrangements, specific well-being initiatives, and their respective impacts on innovation, would provide a richer understanding. Additionally, exploring the role of organizational culture and leadership styles in these dynamics could offer valuable insights. Finally, this study focuses primarily on employees within the digital business sector in a specific geographical region. This limited the generalizability of our findings. Broadening the research to include more diverse industries and regions would enhance the applicability of the results. Furthermore, this study's cross-sectional design captures data at a single point in time, restricting its ability to infer causality.

Future studies should address these limitations by combining qualitative methods. Qualitative approaches, such as interviews and focus groups, can provide deeper insights into the factors that influence employee well-being and work flexibility. Employing techniques such as fsQCA can also enhance the robustness of the theoretical models. An in-depth examination of the specific components of work flexibility and well-being initiatives is needed to better understand their individual and combined effects on innovative behavior and job performance. Exploring the impacts of various leadership styles and organizational cultures on these relationships would further enrich the findings. Additionally, expanding the scope of this study to include a wider range of industries and geographical regions would improve the generalizability of the results. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to establish causal relationships and observe changes over time. Research focusing on different generational segments and their perceptions of work flexibility and well-being could also provide valuable insights into enhancing the overall understanding of these dynamics in the workplace.

References

- Abdullah, M.I.; Huang, D.; Sarfraz, M.; Ivascu, L.; Riaz, A. Effects of internal service quality on nurses' job satisfaction, commitment and performance: Mediating role of employee well-being. Nurs Open 2021, 8, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Raihan, T.; Uddin, A. I.; Uddin, M. A. Predicting Innovative Work Behaviour in an Interactive Mechanism. Behav Sci (Basel) 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B. M.; Cheema, S.; Javed, F. Cultural intelligence and innovative work behavior: the role of work engagement and interpersonal trust. European Journal of Innovation Management 2020, 24, 1082–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidla, A.; Kindsiko, E.; Poltimäe, H.; Hääl, L. To work at home or in the office? Well-being, information flow and relationships between office workers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Facilities Management 2022. [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L. S.; West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-97932-000. 1991.

- Alikaj, A.; Ning, W.; Wu, B. Proactive Personality and Creative Behavior: Examining the Role of Thriving at Work and High-Involvement HR Practices. Journal of Business and Psychology 2020, 36, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSuwaidi, M.; Eid, R.; Agag, G. Understanding the link between CSR and employee green behaviour. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2021, 46, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Torres, F. J.; Schiuma, G. (2022). Measuring the impact of remote working adaptation on employees' well-being during COVID-19: insights for innovation management environments. European Journal of Innovation Management. [CrossRef]

- Ángeles López-Cabarcos, M.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, P.; Quiñoá-Piñeiro, L. M. An approach to employees’ job performance through work environmental variables and leadership behaviours. Journal of Business Research 2022, 140, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M. K.; Yousaf, Z.; Yasir, M.; Sharif, M.; Nasir, M. H.; Rasheed, M. I.; Waheed, J.; Hussain, H.; Majid, A. How to unleash innovative work behavior of SMEs' workers through knowledge sharing? Accessing functional flexibility as a mediator. European Journal of Innovation Management 2020, 25, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aura, N. A. M.; Desiana, P. M. Flexible Working Arrangements and Work-Family Culture Effects on Job Satisfaction: The Mediation Role of Work-Family Conflicts among Female Employees. Jurnal Manajemen Teori dan Terapan | Journal of Theory and Applied Management 2023, 16, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M. R.; Atlasi, R.; Ziapour, A.; Abbas, J.; Naemi, R. Innovative human resource management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review approach. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.; Alan, B.; Bill, H. (2022). Business research methods. Oxford university press.

- Belsley, D. A.; Kuh, E.; Welsch, R. E. (2005). Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential data and sources of collinearity John Wiley & Sons.

- Benitez, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A.; Schuberth, F. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Information & Management 2020, 57, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, M. P. (1964). New York: Wiley, W: Life New York.

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E. I. , Khapova, S. N., Bossink, B. A. G. Servant Leadership and Innovative Work Behavior in Chinese High-Tech Firms: A Moderated Mediation Model of Meaningful Work and Job Autonomy. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D. Does remote work flexibility enhance organization performance? Moderating role of organization policy and top management support. Journal of Business Research 2022, 139, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.; Hwang, H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle C., M. Cutoff criteria for overall model fit indexes in generalized structured component analysis. Journal of Marketing Analytics 2020, 8, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, S. J. L.; Myeda, N. E.; Teo, Y. X. Facilities management: towards flexible work arrangement (FWA) implementation during Covid-19. Journal of Facilities Management 2022, 21, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E. L. , Daniels, S. R., Hall, A. V. Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Academy of Management Annals 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevalia, M.; Alib, F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, A. A.; Apostu, S.-A.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work Flexibility, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance among Romanian Employees—Implications for Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, T.; Duan, C. Behavioural and economic impacts of end-user computing satisfaction: Innovative work behaviour and job performance of employees. Computers in Human Behavior 2022, 136, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital, Economy P. A. (2023). List of registered digital entrepreneurs. https://www.depa.or.

- Dul, J. Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA). Organizational Research Methods 2015, 19, 10–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ererdi, C.; Wang, S.; Rofcanin, Y.; Las, Heras, M. Understanding flexibility i-deals: integrating performance motivation in the context of Colombia. Personnel Review 2022, 52, 1094–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakfare, P.; Manosuthi, N.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, S.-M.; Han, H. (2024). Investigating the Formation of Ethical Animal-Related Tourism Behaviors: A Self-Interest and Pro-Social Theoretic Approach. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker D., F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frare, A. B.; Beuren, I. M. Effects of corporate reputation and social identity on innovative job performance. European Journal of Innovation Management 2021, 25, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A. S.; Erickson, R. J.; Diefendorff, J. M.; Krantz, D. When does feeling in control benefit well-being? The boundary conditions of identity commitment and self-esteem. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2020, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Dhar, R. Employee service innovative behavior. International Journal of Manpower 2017, 38, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F.; Howard, M. C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halinski, M.; Duxbury, L. Workplace flexibility and its relationship with work-interferes-with-family. Personnel Review 2019, 49, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartner-Tiefenthaler, M.; Mostafa A. M., S. , Koeszegi, S. T. The double-edged sword of online access to work tools outside work: The relationship with flexible working, work interrupting nonwork behaviors and job satisfaction. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1035989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R. (2017). Decent work and the digital gig economy: a developing country perspective on employment impacts and standards in online outsourcing, crowdwork, etc.. Development Informatics Working Paper no 7. Manchester: Global Development Institute SEED, University of Manchester., Available at: http://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/ publications/workingpapers/di/di_wp71. pdf.

- Homans. G. C. THE EXPLANATION OF ENGLISH REGIONAL DIFFERENCES. Past and Present 1969, 42, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G. C. Social behavior as exchange. American journal of sociolog 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoonakker, P.; Carayon, P. Questionnaire Survey Nonresponse: A Comparison of Postal Mail and Internet Surveys. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 2009, 25, 348–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huws, U.; Spencer, N.; Joyce, S. (2016). Crowd work in Europe: preliminary results from a survey in the UK, Sweden, Germany, Austria and the Netherlands. FEPS Studies, December. Available at: http://www.feps-europe.eu/assets/, 1 March.

- Hwang, H.; Cho, G.; Choo, H. (2023a). Hwang, H., Cho, G., & Choo, H. (2023). GSCA Pro (Version1.2.1). http://www.gscapro.com.

- Hwang, H.; Sarstedt, M.; Cho, G.; Choo, H.; Ringle C., M. A primer on integrated generalized structured component analysis. European Business Review 2023, 35, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, D. A.; Sari, P. Employee productivity: The effect of flexible work arrangement, indoor air quality, location and amenities at one of multinational logistics providers in Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 729, 012126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P. Cultural intelligence and innovative work behavior: examining multiple mediation paths in the healthcare sector in India. Industrial and Commercial Training 2022, 54, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Sengupta, S.; Panda, M.; Hati, L.; Prikshat, V.; Patel, P.; Mohyuddin, S. (2022). Teleworking: role of psychological well-being and technostress in the relationship between trust in management and employee performance. International Journal of Manpower. [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, J. The impact of coaching on well-being andperformance of managers and their teamsduring pandemic. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring 2021, 19, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kässi, O.; Lehdonvirta, V. (2016). Online labour index: measuring the online gig economy for policy and research. Paper presented at Internet, Politics & Policy, Oxford. Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/74943/1/MPRA_paper_74943.pdf (accessed 1 March 2018)., 22–23 September.

- Kim, M.-S.; Koo, D.-W. Linking LMX, engagement, innovative behavior, and job performance in hotel employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2017, 29, 3044–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. Corporate social responsibility, employee engagement, well-being and the task performance of frontline employees. Management Decision 2020, 59, 2040–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Examining Structural Relationships between Work Engagement, Organizational Procedural Justice, Knowledge Sharing, and Innovative Work Behavior for Sustainable Organizations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmieciak, R. Trust, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior: empirical evidence from Poland. European Journal of Innovation Management 2020, 24, 1832–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroglu, Ş.; Ozmen, O. The mediating effect of work engagement on innovative work behavior and the role of psychological well-being in the job demands–resources (JD-R) model. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 2021, 14, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosec, Z.; Sekulic, S.; Wilson-Gahan, S.; Rostohar, K.; Tusak, M.; Bon, M. Correlation between Employee Performance, Well-Being, Job Satisfaction, and Life Satisfaction in Sedentary Jobs in Slovenian Enterprises. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, V.; Sreejesh, S. Co-worker and customer incivility on employee well-being: Roles of helplessness, social support at work and psychological detachment- a study among frontline hotel employees. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 56, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. W. Impact of competitiveness on salespeople's commitment and performance. Journal of Business Research 2012, 65, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Y.; Bonn, M. A.; Reid, E. L.; Kim, W. G. Differences in tourist ethical judgment and responsible tourism intention: An ethical scenario approach. Tourism Management 2017, 60, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Y.; Sun, R.; Tao, W.; Lee, Y. Employee coping with organizational change in the face of a pandemic: The role of transparent internal communication. Public Relat Rev 2021, 47, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Kim, J.; Na, S. How Ethical Leadership Cultivates Innovative Work Behaviors in Employees? Psychological Safety, Work Engagement and Openness to Experience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosuthi, N.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, H. An innovative application of composite-based structural equation modeling in hospitality research with empirical example. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 2021, 62, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, T. I.; Manaf, N. H. B. A.; Haque, A. K. M. A.; Maulan, S. B. Factors affecting attitudes towards using ride-sharing apps. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law 2021, 25, 60-70.

- Miao, R.; Cao, Y. High-Performance Work System, Work Well-Being, and Employee Creativity: Cross-Level Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Bhatnagar, J.; Gupta, R.; Wadsworth S., M. How work–family enrichment influence innovative work behavior: Role of psychological capital and supervisory support. Journal of Management & Organization 2019, 25, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, H.; Hobbs F. D., R. , Padilla, F., Arbetter, D., Templeton, A., Seegobin, S., Kim, K., Campos, J. A. S., Arends, R. H., Brodek, B. H., Brooks, D., Garbes, P., Jimenez, J., Koh, G., Padilla, K. W., Streicher, K., Viani, R. M., Alagappan, V., Pangalos, M. N., Esser, M. T., group, T. s. Efficacy and safety of intramuscular administration of tixagevimab-cilgavimab for early outpatient treatment of COVID-19 (TACKLE): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2022, 10, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, L. F.; Bakti, R.; Febriyantoro, M. T.; Kraugusteeliana, K.; Ausat, A. M. A. DO INNOVATIVE WORK BEHAVIOR AND ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT CREATE BUSINESS PERFORMANCE: A LITERATURE REVIEW. Community Development Journal: Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat 2023, 4, 713–717. [Google Scholar]

- Nazir, S.; Shafi, A.; Atif, M. M. , Qun, W., Abdullah, S. M. (2019). How organization justice and perceived organizational support facilitate employees’ innovative behavior at work. Employee Relations: The International Journal. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P. V.; Le, H. T. N.; Trinh, T. V. A.; Do, H. T. S. The Effects of Inclusive Leadership on Job Performance through Mediators. Asian Academy of Management Journal 2019, 24, 63–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Barbeitos, I.; Calado, A. The role of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations in sharing economy post-adoption. Information Technology & People 2021, 35, 165–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachec, P. O.; Montece, D. C.; Tello, M. Psychological Empowerment and Job Performance: Examining Serial Mediation Effects of Self-Efficacy and Affective Commitment. Administrative Sciences 2023, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnitvitidkun, P.; Ponchaitiwat, K.; Chancharat, N.; Thoumrungroje, A. Understanding IT professional innovative work behavior in the workplace: A sequential mixed-methods design. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2024, 10, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R. K.; Hati, L. The Measurement of Employee Well-being: Development and Validation of a Scale. Global Business Review 2019, 23, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quade, M. J.; McLarty, B. D.; Bonner, J. M. The influence of supervisor bottom-line mentality and employee bottom-line mentality on leader-member exchange and subsequent employee performance. Human Relations 2020, 73, 1157–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, S.; Khan, N. R.; Soomro, S. A.; Masood, F. (2022). Linking LMX and schedule flexibility with employee innovative work behaviors: mediating role of employee empowerment and response to change. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S. F.; Wang, M.; Tang, M.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, J. How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, T. K.; Pana-Cryan, R. Work Flexibility and Work-Related Well-Being. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N. F.; Schubring, S.; Hauff, S.; Ringle, C. M.; Sarstedt, M. When predictors of outcomes are necessary: guidelines for the combined use of PLS-SEM and NCA. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2020, 120, 2243–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridwan Maksum, I.; Yayuk Sri Rahayu, A.; Kusumawardhani, D. A Social Enterprise Approach to Empowering Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Indonesia. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, A.; Sutton, A.; Medvedev O., N. The role of dispositional mindfulness in employee readiness for change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Organizational Change Management 2021, 34, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanlioz, E.; Sagbas, M.; Surucu, L. The Mediating Role of Perceived Organizational Support in the Impact of Work Engagement on Job Performance. Hosp Top 2023, 101, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A. S.; Reis Neto, M. T.; Verwaal, E. Does cultural capital matter for individual job performance? A large-scale survey of the impact of cultural, social and psychological capital on individual performance in Brazil. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2018, 67, 1352–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridakis, G.; Lai, Y.; Muñoz, T.o.r.r. es, R. I.; Gourlay, S. Exploring the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: an instrumental variable approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2020, 31, 1739–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, R.; Bhanugopan, R.; van der Heijden, B. I. J. M.; Farrell, M. Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: The mediating effect of innovative work behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2017, 100, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. K.; Giudice, M. D.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. K.; Pradhan, R. K.; Panigrahy, N. P.; Jena, L. K. Self-efficacy and workplace well-being: moderating role of sustainability practices. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2019, 26, 1692–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibah, D.; Ho, T. C. F. The Moderating Effect of Flexible Work Option on Structural Empowerment and Generation Z Contextual Performance. Behav Sci (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Marsh, G.; Nicole, D.; Broadbent, P. (2017). Good Work: The Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/good-workthe-taylor-review-of-modern-working-practices (accessed, 1 March.

- Wen, Q.; Wu, Y.; Long, J. Influence of Ethical Leadership on Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Role of Organization-Based Self-Esteem and Flexible Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S.; Deng, H.; Duan, S. Understanding Digital Work and its Use in Organizations from a Literature Review. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2022, 14, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. J.; Graham, M.; Lehdonvirta, V.; Hjorth, I. Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy. Work Employ Soc 2019, 33, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Majid, A.; Yousaf, Z.; Nassani, A. A. , Haffar, M. An integrative framework of innovative work behavior for employees in SMEs linking knowledge sharing, functional flexibility and psychological empowerment. European Journal of Innovation Management 2021, 26, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-N.; Li, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-H.; Ruan, W.-Q. Critical factors in the identification of word-of-mouth enhanced with travel apps: the moderating roles of Confucian culture and the switching cost view. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 2019, 24, 422–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Gong, Z. Radical and incremental creativity: associations with work performance and well-being. European Journal of Innovation Management 2020, 24, 968–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zychlinski, E.; Lavenda, O.; Shamir, M. M. , Kagan, M. Psychological Distress and Intention to Leave the Profession: The Social and Economic Exchange Mediating Role. The British Journal of Social Work 2021, 51, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).