Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Escherichia Coli Isolates Identification

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Escherichia Coli Isolates Identification

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

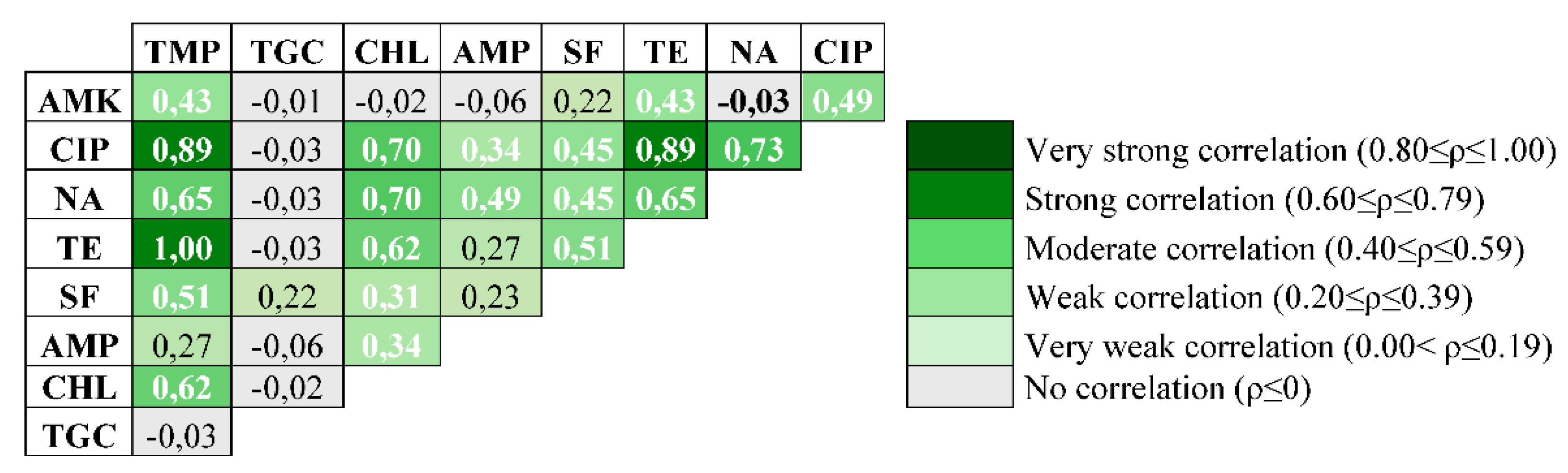

3.3. Statistical Análisis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fariñas Guerrero, Fernando.; Astorga Márquez, Rafael Jesús. Zoonosis transmitidas por animales de compañía. Una guía de consulta para el profesional sanitario. Zaragoza (España). Editorial Amazing Books. 2019. ISBN.: 978-84-174043-32-4.

- Li, Yanli. ; Fernández, Rubén.; Durán, Inma.; Molina-López, Rafael A.; Darwich, Laila. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria Isolated from Cats and Dogs from the Iberian Peninsula. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, C.V.; Scarlett, J.M.; Wade, S.E.; McDonough, P. Prevalence of enteric zoonotic agents in cats less than 1 year old in central New York state. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2001, 15, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philbey, A.W.; Brown, F.M.; Mather, H.A.; Coia, J.E.; Taylor, D.J. Salmonellosis in cats in the United Kingdom: 1955 to 2007, Vet. Rec. 2009, 164, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otranto, D.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Mihalca, A.D.; Traub, R.J.; Lappin, M.; Baneth, G. Zoonotic parasites of sheltered and stray dogs in the era of the global economic and political crisis. Trends Parasitol. 2017, 33, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, Ricardo G. ; Halls, Vicky.; Krämer, Friederike.; Lappin, Micahel.; Pennisi, Maria Grazia.; Peregrine, Andrew S.; … & Wright, Ian. Vector-borne and other pathogens of potential relevance disseminated by relocated cats. Parasit. Vectors. 2022, 15, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhold, R.W.; Jessup, D.A. Zoonotic diseases associated with Free-Roaming cats. Zoonoses Public Health. 2013, 60, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.; García, M.; Gálvez, R.; Checa, R.; Marino, V.; Sarquis, J.; Miró, J. Implications of zoonotic and vector-borne parasites to free-roaming cats in central Spain. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 251, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, A.; Bhekharee, A.K.; Feng, M.; Cheng, X.; Halim, M. Prevalence of zoonotic pathogens in domestic and feral cats in Shanghai, with Special Reference to Salmonella. J. Health Res. 2021, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Caxito, M.; Benavides, J.A.; Adell, A.D.; Paes, A.C.; Moreno-Switt, A.I. Global Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Producing-Escherichia Coli in Dogs and Cats—A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. One Health. 2021, 12, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateo, A.; Zappaterra, M.; Covella, A.; Padalino, B. Factors Influencing Stress and Fear-Related Behaviour of Cats during Veterinary Examinations. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario, Inmaculada. ; Calcines, María Isabel.; Rodríguez-Ponce, Eligia.; Déniz, Soraya.; Real, Fernando.; Vega, Santiago.; Marín, Clara.; Padilla, Daniel.; Martín, José L.; Acosta-Hernández, Begoña. Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotypes isolated for the first time in feral cats: The impact on public health. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 84, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, G.; Stranieri, A.; Penati, M.; Dall’ara, P.; Luzzago, C.; Lauzi, S. Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Producing Escherichia coli Stray cats from Northern Italy. IJID. 2022, 116, S1–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, Valeria. ; Gambino, Delia.; Orefice, Tiziana.; Cirincione, Roberta.; Castelli, Germano.; Bruno, Federica.; … & Casata, Giovani. ¿Can Stray Cats Be Reservoirs of Antimicrobial Resistance? Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2021/578 Supplementing Regulation (EU) 2019/6 of the European Parliament and of the Council Regarding Requirements for the Collection of Data on the Volume of Sales and on the Use of Antimicrobial Medicinal Products in Animals; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mader, R.; Muñoz Madero, C.; Aasmäe, B.; Bourély, C.; Broens, E.M.; Busani, L.; Callens, B.; Collineau, L.; Crespo-Robledo, P.; Damborg, P. ; Review and Analysis of National Monitoring Systems for Antimicrobial Resistance in Animal Bacterial Pathogens in Europe: A Basis for the Development of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network in Veterinary Medicine (EARS-Vet). Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 838490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto Ferreira, J. Why Antibiotic Use Data in Animals Needs to Be Collected and How This Can Be Facilitated. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plan estratégico 2025-2027 del Plan Nacional frente a la Resistencia a los Antibióticos (PRAN). Mayo 2025. NIPO: 134-25-015-4.

- Guardabassi, L. Pet Animals as Reservoirs of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria: Review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damborg, P.; Broens, E.M.; Chomel, B.B.; Guenther, S.; Pasmans, F.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Weese, J.S.; Wieler, L.H.; Windahl, U.; Vanrompay, D.; Guardabassi, L. Bacterial Zoonoses Transmitted by Household Pets: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives for Targeted Research and Policy Actions. J. Comp. Pathol. 2016, 155, S27–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.L.; Buldain, D.; Castillo, L.G.; Buchamer, A.; Chirino-Trejo, M.; Mestorino, N. Pet and Stray Dogs as Reservoirs of Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia coli. Int. J. Microbiol. 2021, 2021, 6664557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Fuertes, Ana. ; Marin, Clara.; Lorenzo-Rebenaque, Laura.; Vega, Santiago.; Montoro-Dasi, Laura. Antimicrobial Resistance in Companion Animals: A New Challenge for the One Health Approach in the European Union. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwich, Laila. ; Seminati, Chiara.; Burballa, Ares.; Nieto, Alba.; Durán, Inma.; Tarradas, Núria.; Molina-López, Rafael A. Antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial isolates from urinary tract infections in companion animals in Spain. Vet. Rec. 2021, 188, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Fuertes, A.; Jordá, J.; Marin, C.; Lorenzo-Rebenaque, L.; Montoro-Dasi, L.; Vega, S. Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Strains to Last Resort Human Antibiotics Isolated from Healthy Companion Animals in Valencia Region. Antibiotics. 2023, 12, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO's List of Medically Important Antimicrobials: a risk management tool for mitigating antimicrobial resistance due to non-human use. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Categorisation of Antibiotics Used in Animals Promotes Responsible Use to Protect Public and Animal Health. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/categorisation-antibiotics-used-animals-promotes-responsible-use-protect-public-animal-health (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Matos, A.; Cunha, E.; Baptista, L.; Tavares, L.; Oliveira, M. ESBL-Positive Enterobacteriaceae from Dogs of Santiago and Boa Vista Islands, Cape Verde: A Public Health Concern. Antibiotics. 2023, 12, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coragem da Costa, Romay. ; Guerra Cunha, Francisca.; Abreu, Raquel.; Pereira, Gonçalo.; Geraldes, Catarina.; Cunha, Eva.; Chambel, Lélia.; Oliveira, Manuela. Insights into Molecular Profiles, Resistance Patterns, and Virulence Traits of Staphylococci from Companion Dogs in Angola. Animals. 2025, 15, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, G.; Dunkler, D. Five Myths about Variable Selection. Transpl. Int. 2017, 30, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley 7/2023, de 28 de marzo, de protección de los derechos y el bienestar de los animales. (B.O.E. N.º 75, miércoles 29 de marzo de 2023).

- European Food Safety Authority. Monitoring AMR in Escherichia coli [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Oct1]. Available from: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/788684f1e7cd48f09238101536577dc4/.

- Tawfick, MM.; Elshamy, AA.; Mohamed, KT.; El Menofy, NG. Gut Commensal Escherichia coli, a High- Risk Reservoir of Transferable Plasmid-Mediated Antimicrobial Resistance Traits. Infect Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, FJ.; Widiasih, DA.; Mentari, AO.; Isnaeni, M.; Qurratu’ain, SH.; Jalal, I.; Islam, AF.; Fardinasyah, A.; Nguyen-Viet, H. Multidrug Resistance in Stray Cats of The NorthSurabaya Region, East Java, Indonesia. World Vet J. 2024, 14, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Bo-Youn.; Md. Sekendar Ali, Dong-Hyeon Kwon, Ye-Eun Heo, Yu-Jeong Hwang, Ji-In Kim, Yun Jin Lee, Soon-Seek Yoon, Dong-Chan Moon, and Suk-Kyung Lim. Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli Isolated from Healthy Dogs and Cats in South Korea, 2020–2022. Antibiotics. 2023, 13, 27. [CrossRef]

- Matope, Gift. ; Chaima, Kudzai.; Bande, Beauty.; Bare, Winnet.; Kadzviti, Faith.; Jinjika, Farai.; Tivapasi, Musavenga. Isolation of multi-drug-resistant strains of Escherichia coli from faecal samples of dogs and cats from Harare, Zimbabwe. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Samudio, V.; Pimentel-Peralta, G.; De La Cruz, A, Landires I. Multidrug-resistant phenotypes of genetically diverse Escherichia coli isolates from healthy domestic cats. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 11260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Feng, M.; Liao, S.; Zheng, Z.; Jia, C.; Zhou, X.; Nambiar, RB.; Ma, Z.; Yue, M.A. Cross-Sectional Study of Companion Animal-Derived Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli in Hangzhou, China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0211322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, MH.; Siddique, AB.; Zihadi, MAH. ; Ahmed, SMS.; Sumon, MSH.; Ahmed, S. Prevalence and molecular characterization of multi-drug and extreme drug-resistant Escherichia coli in companion animals in Bangladesh. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 16419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buranasinsup, Shutipen. ; Wiratsudakul, Anuwat.; Chantong, Boonrat.; Maklon, Khuanwalai.; Suwanpakdee, Sarin.; Jiemtaweeboon, Sineenard.; Sakcamduang, Walasinee. Prevalence and characterization of antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from veterinary staff, pets, and pet owners in Thailand. J. Infect. Public Health. 2023, 194-202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzewusk, Magdalena.; Czopowicz, Micha.; Kizerwetter-Uwida, Magdalena.; Chrobak, Dorota.; Baszczak, Borys.; Binek, Marian. Multidrug Resistance in Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Infections in Dogs and Cats in Poland (2007-2013). Sci. World J. 2015,. [CrossRef]

- Ruch-Gallie, Rebecca A. ; Veir, Jukia K.; Spindel, Miranda E.; Lappin, Michael R. Efficacy of amoxycillin and azithromycin for the empirical treatment of shelter cats with suspected bacterial upper respiratory infections. JFMS. 2008, 10, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattasathuchana, P.; Srikullabutr, S.; Kerdsin, A.; Assawarachan, S.N.; Amavisit, P.; Surachetpong, W.; Thengchaisri, N. Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli in cats and their drinking water: drug resistance profiles and antimicrobial-resistant genes. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njamkepo, Elisabeth.; Fabre, Laetitia.; Lim, Catherine.; Peteux, Claire.; Le Chevalier Sontag, Lucile.; Larsen, Alice.; Weill, Francois-Xavier.; Le Hello, Simon. Emerging resistance to azithromycin in non-typhoidal Salmonella: the example of a multidrug-resistant S. enterica serotype Blockley strain. I3S Int. Symp. Salmonella and Salmonellosis. 2016. June 6-7-8, 2016 Saint-Malo, France.

- Nair, Satheesh.; Ashton, Philip.; Doumith, Michel.; de Pinna, Elizabeth.; Day Martin. Whole Genome Sequencing for antimicrobial drug surveillance: Prevalence of azithromycin resistance in a U.K. population of Non Typhoidal Salmonella. 2016. I3S Int. Symp. Salmonella and Salmonellosis. June 6-7-8, 2016 Saint-Malo, France.

- Sobkowich, KE.; Hui, AY.; Poljak, Z.; Szlosek, D.; Plum, A.; Weese, JS. Nationwide analysis of methicillin-resistant staphylococci in cats and dogs: resistance patterns and geographic distribution. Am J Vet Res. 2025, 86(3), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, John. L. (et al). Pharmaceutical pollution of the world’s rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (PNAS). 2022, 119, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Xinyang. ; Toro, Magaly.; Reyes-Jara, Angelica.; Moreno-Switt,Andrea I.; Adell, Aiko D.; Oliveira, Celso J.B.; Bonelli, Raquel R.; Gutierrez,Sebastian.; Alvarez, Francisca P.; de Lima Rocha, Alan Douglas.; Kraychete, Gabriela B.; Chen, Zhao.; Grim, Christopher.; Brown, Eric.; Bellg, Rebecca.; Meng, Jianghong. Integrative genome-centric metagenomics for surface water surveillance: Elucidating microbiomes, antimicrobial resistance, and their associations. Water Res. 2024, 264, 122208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, B.; Phillips, M.; Mowery, H.; Jones-Lepp, T. Contamination profiles and mass loadings of macrolide antibiotics and illicit drugs from a small urban wastewater treatment plant. Chemosphere. 2009, 75(1), 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS). Centro de Información online de Medicamentos de la AEMPS (CIMA). 2025. https://cima.aemps.es/cima/publico/home.html.

- Zhou, Y.; Ji, X.; Liang, B.; Jiang, B.; Li, Y.; Yuan, T.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Guo, X.; Sun, Y. Antimicrobial Resistance and Prevalence of Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli from Dogs and Cats in Northeastern China from 2012 to 2021. Antibiotics. 2022, 11, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittayasut, N.; Yindee, J.; Boonkham, P.; Yata, T.; Suanpairintr, N.; Chanchaithong, P. Multiple and High-Risk Clones of Extended- Spectrum Cephalosporin-Resistant and Blandm-5-Harbouring Uropathogenic Escherichia coli from Cats and Dogs in Thailand. Antibiotics. 2021, 10, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AMA Group | AMA | EMA* | N.º Strains and Percentage (%) | |

| S | R | |||

| Aminoglycosides | GEN | C | 68/68 (100) | 0/68 (0) |

| AMK | C | 67/68 (98.5) | 1/68 (1.5) | |

| Cephalosporins | CTX | B | 68/68 (100) | 0/68 (0) |

| CAZ | B | 68/68 (100) | 0/68 (0) | |

| Quinolones | CIP | B | 64/68 (94.1) | 4/68 (5.9) |

| NA | B | 63/68 (92.6) | 5/68 (7.4) | |

| Tetracyclines | TE | D | 63/68 (92.6) | 5/68 (7.4) |

| Sulphonamides | SF | D | 51/68 (75) | 17/68 (25) |

| Aminopenicillins | AMP | D | 54/68 (79.4) | 14/68 (20.6) |

| Carbapenems | MEM | A | 68/68 (100) | 0/68 (0) |

| Macrolides | AZM | C | 0/68 (0) | 68/68 (100) |

| Polymyxins | CL | B | 68/68 (100) | 0/68 (0) |

| Amphenicols | CHL | C | 67/68 (98.5) | 1/68 (1.5) |

| Glycylcyclines | TGC | A | 67/68 (98.5) | 1/68 (1.5) |

| Diaminopyrimidines | TMP | D | 63/68 (92.6) | 5/68 (7.4) |

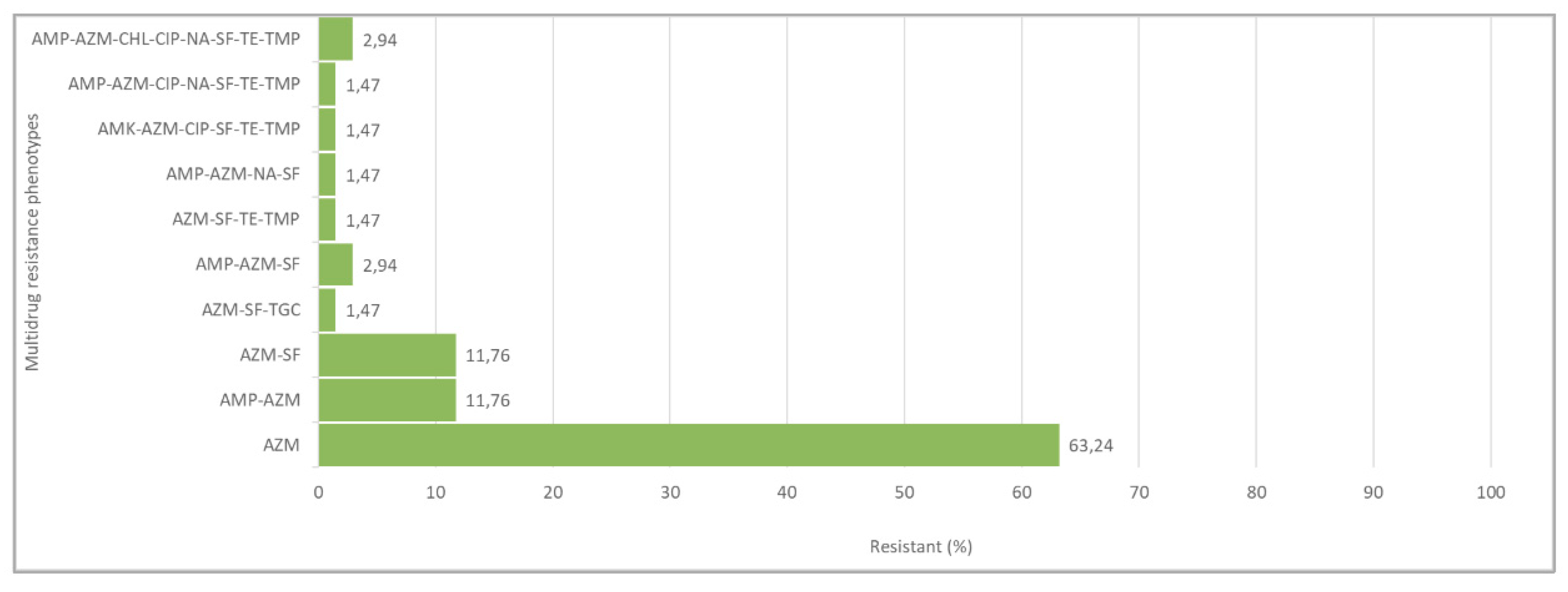

| N of Isolates | AMR Phenotypes | N Antimicrobials |

| 43 | AZM | 1 |

| 8 | AMP-AZM | 2 |

| 8 | AZM-SF | 2 |

| 1 | AZM-SF-TGC | 3 |

| 2 | AMP-AZM-SF | 3 |

| 1 | AZM-SF-TE-TMP | 4 |

| 1 | AMP-AZM-NA-SF | 4 |

| 1 | AMK-AZM-CIP-SF-TE-TMP | 6 |

| 1 | AMP-AZM-CIP-NA-SF-TE-TMP | 7 |

| 2 | AMP-AZM-CHL-CIP-NA-SF-TE-TMP | 8 |

| Total 68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).