Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- To date, cBP-Tnet was the only deep learning method with automatic photoplethysmogram feature extraction to have both Systolic (4.32 mmHg) and Diastolic (2.18 mmHg) blood pressure acceptable to the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) international standards (<5 mmHg, >85 subjects) [19].

- 2.

- 3.

- The cBP-Tnet method efficiently takes 13.67% faster to train and still output better and AAMI accepted results compared to recent studies [5] in the field.

2. Related Works

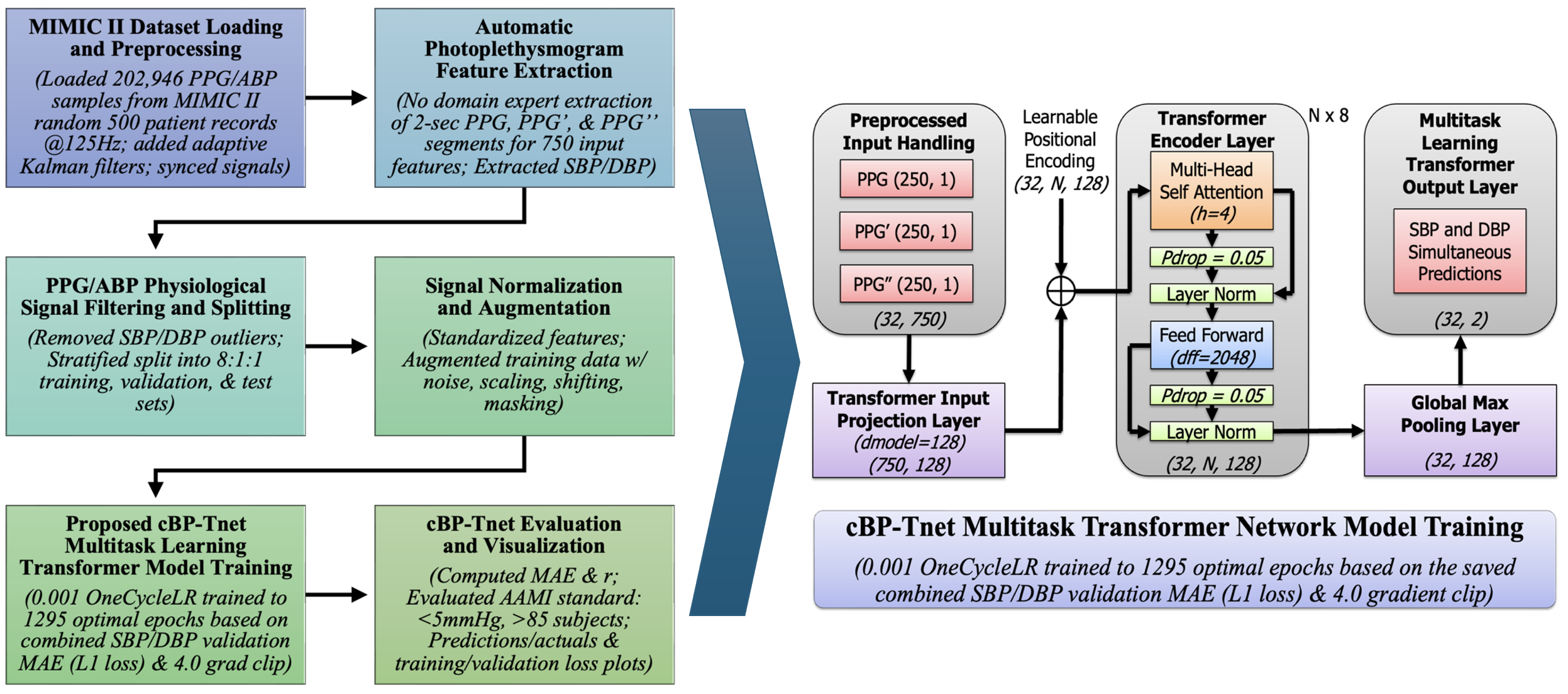

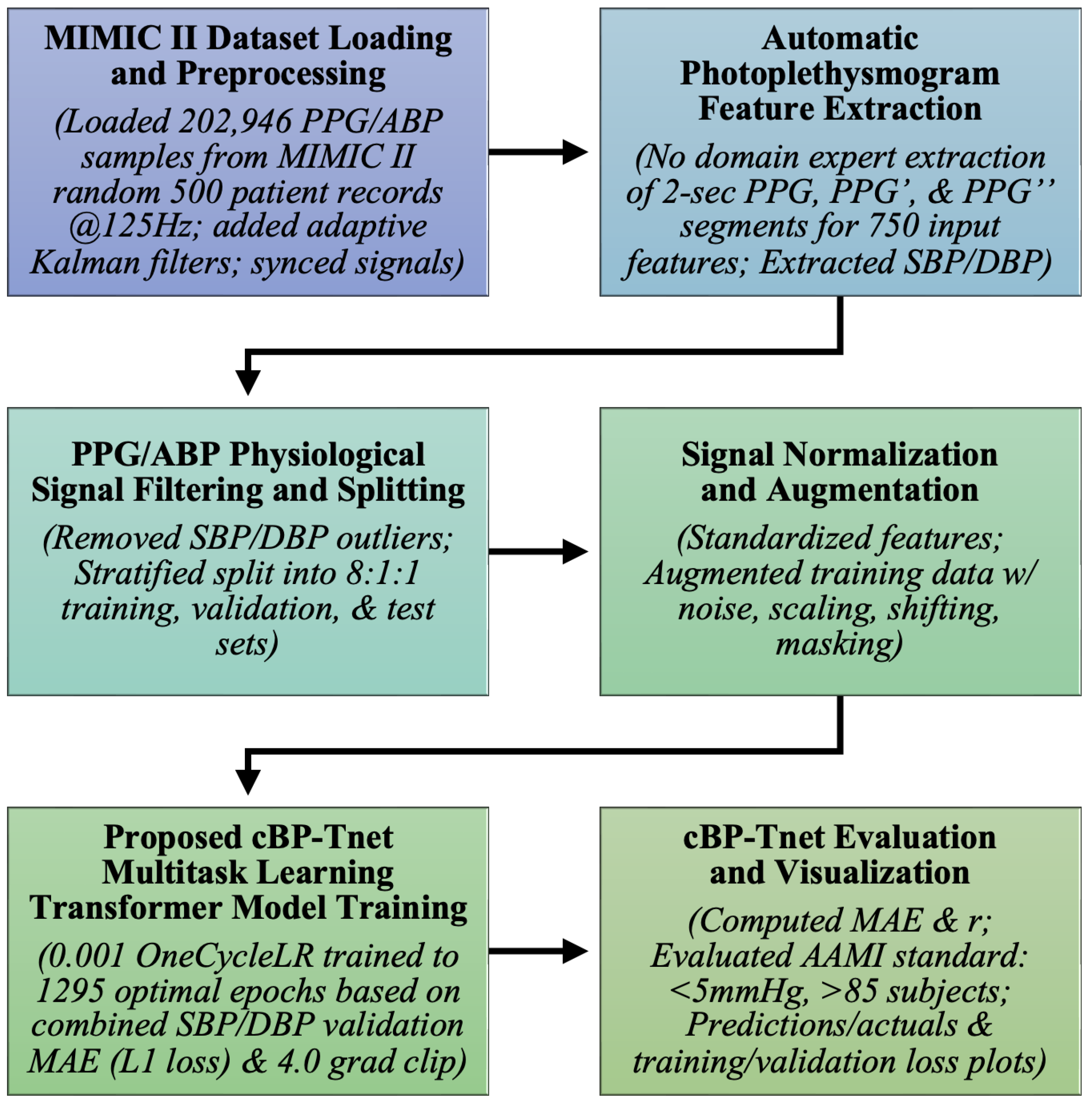

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. MIMIC II Dataset Loading and Preprocessing

3.2. Automatic Photoplethysmogram Feature Extraction

3.3. PPG/ABP Data Filtering and Splitting

3.4. Signal Normalization and Augmentation

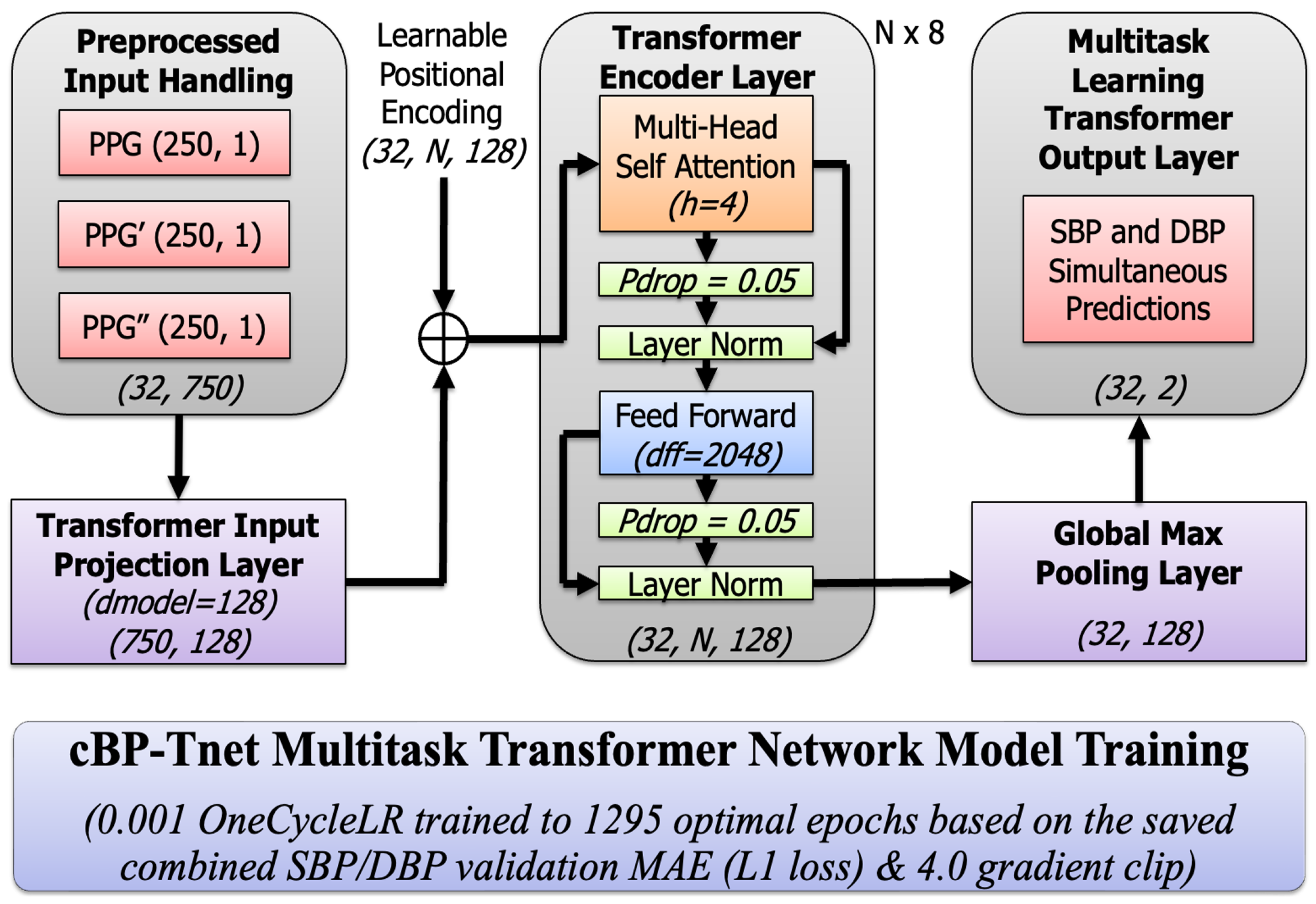

3.5. Proposed cBP-Tnet Multitask Transformer Model Training

3.5.1. Input Projection and Positional Encoding

3.5.2. Multi-Head Scaled Dot-Product Attention

3.5.3. Residual Connections and Layer Normalization

3.5.4. Position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN)

3.5.5. Global Max Pooling layer

3.5.6. Multi-task Learning Output Layer

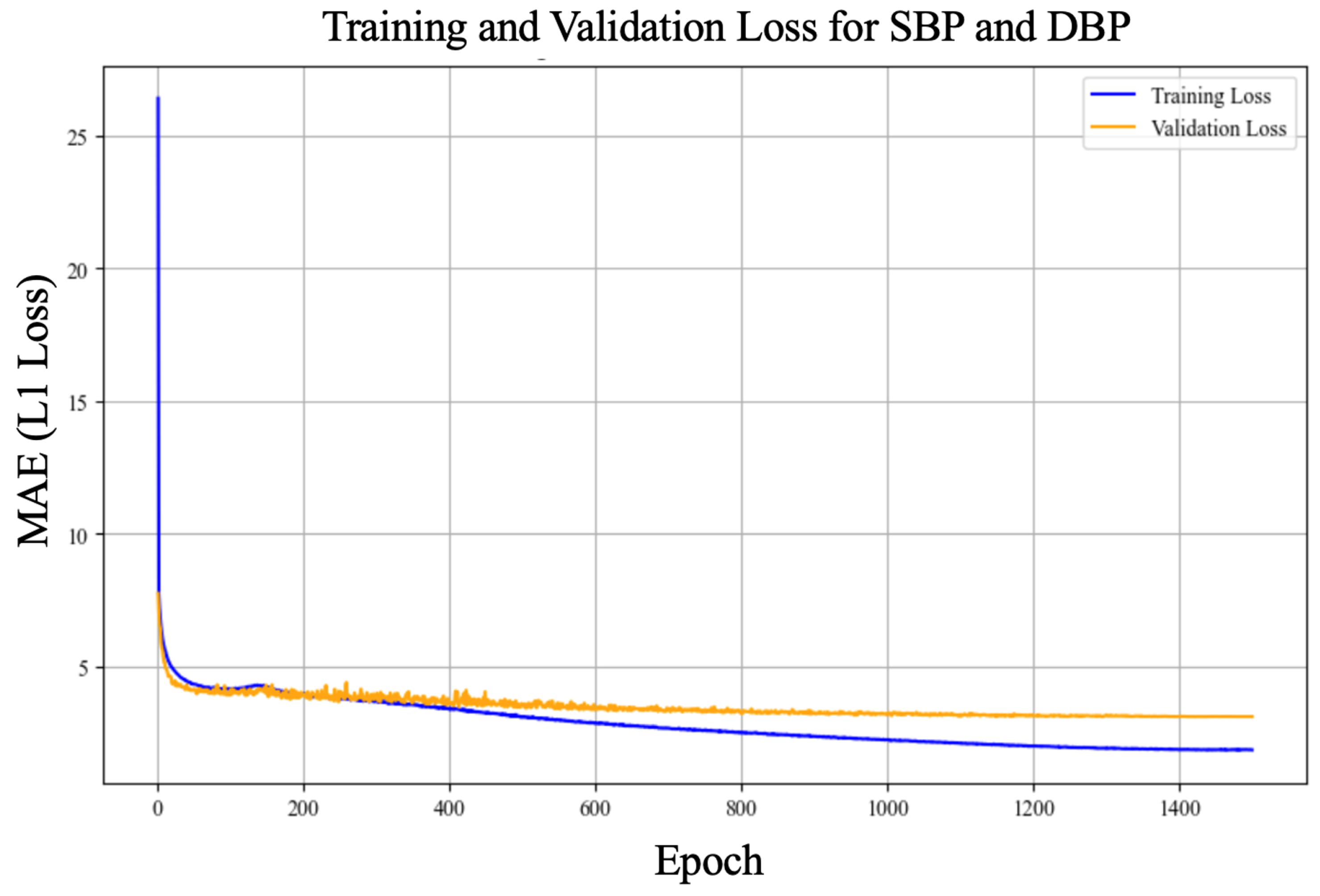

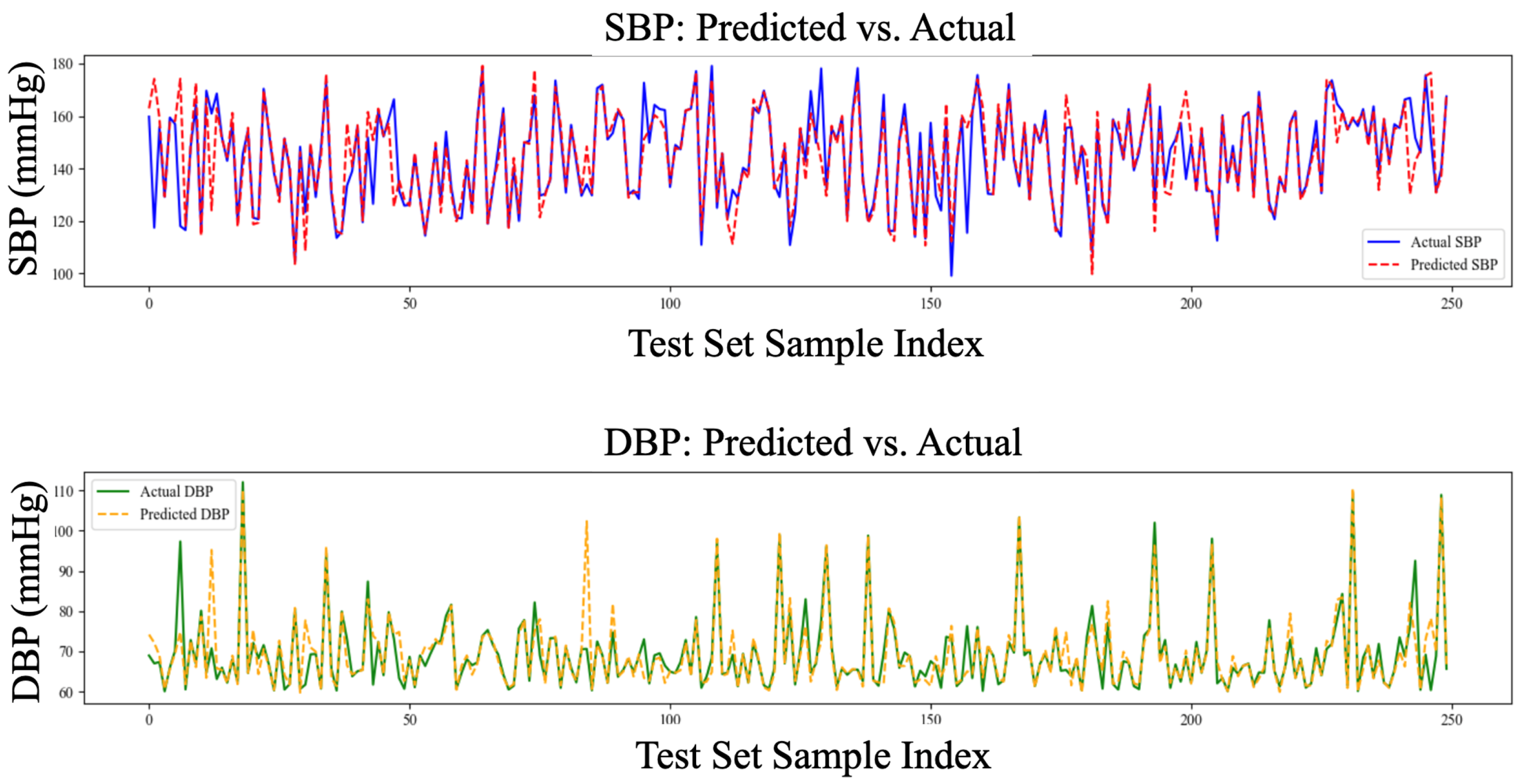

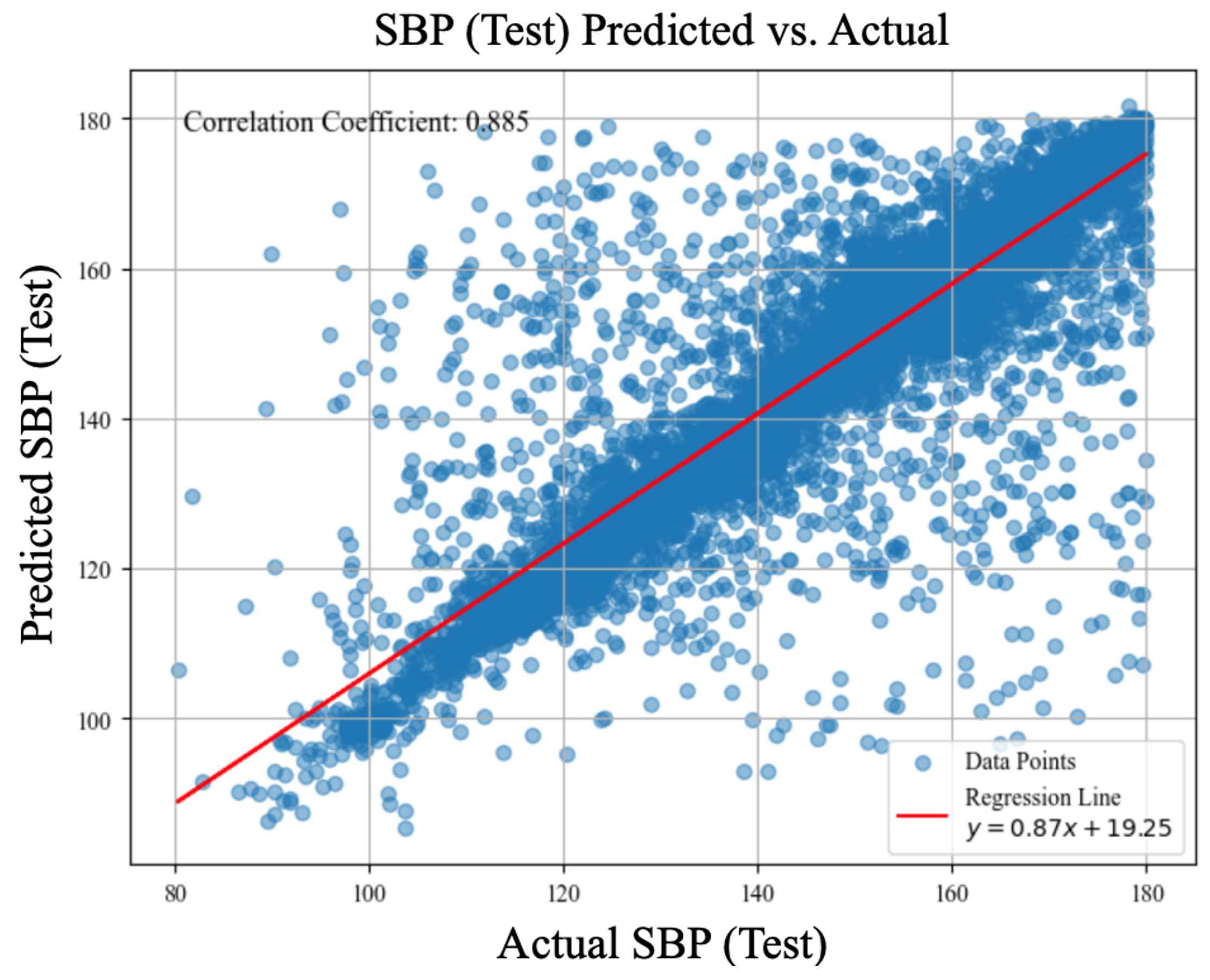

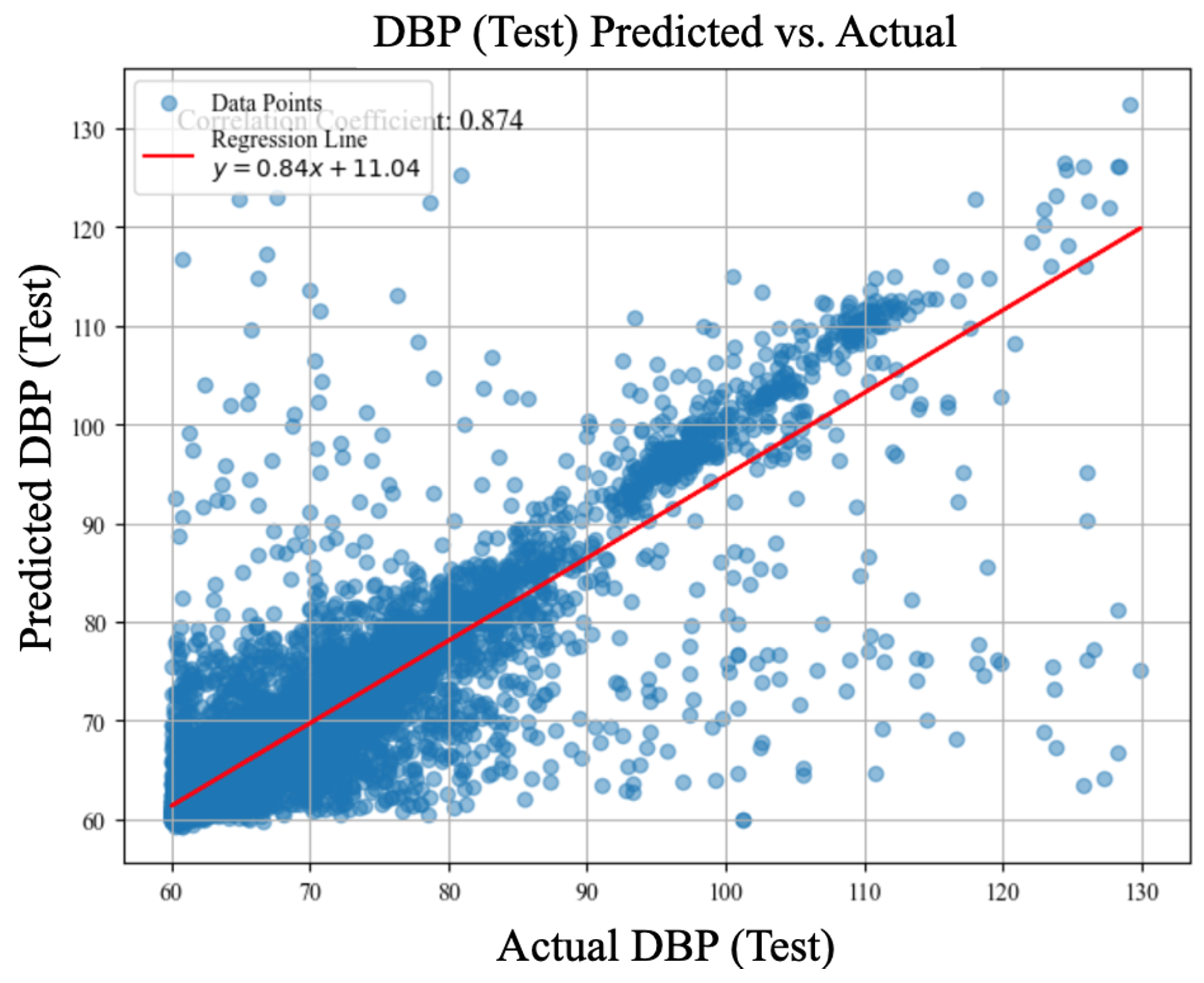

4. cBP-Tnet Experimental Results and Discussions

4.1. Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO) Experiments

4.2. Hyperparameter Tuning/Analysis

4.3. Comparison Against Related Deep Learning Methods to Estimate Blood Pressure with Automatic Feature Extraction using Photolethysmogram Feature Extraction

4.4. cBP-Tnet Evaluation and Visualization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIMIC-II | Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care II |

| TCN-CBAM | Temporal Convolutional Network- Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| MTFF-ANN | Multi-type Features Fusion Artificial Neural Network |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| AAMI | Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation |

| Resnet | Residual Neural Network |

| mmHg | Millimetre of Mercury |

| LOSO | Leave-One-Subject-Out |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| BCG | Ballistocardiogram |

| PPG | Photoplethysmogram |

| MTL | Multi-Task Learning |

| PTT | Pulse Transit Time |

| PWV | Pulse Wave Velocity |

| ABP | Arterial Blood Pressure |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| r | Pearson correlation coefficient |

Short Biography of Authors

|

Angelino A. Pimentel received his B.Sc. in Electronics Engineering (ECE) degree from Saint Mary’s University (SMU), Nueva Vizcaya, Philippines, in 2014. His M.Sc. in Electronics Engineering degree from Mapua University (MU), Manila, Philippines, in 2019. He is currently pursuing Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering, specifically researching in Biomedical Electronic Center at the Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology (STUST), Tainan City, Taiwan. From 2015, he began his career as an In-process Quality Engineer at SFA Semicon, a subsidiary SAMSUNG company in Pampanga City, Philippines. Since 2017, he has been a researcher/faculty, serving also as the Head of the Electronics Engineering Department & Technology Transfer and Business Development Office (TTBDO) at SMU. His research interests are in Intelligent Biomedical Electronic Devices and Post-harvest Collaborative Robotic (Cobot) e-Systems. |

|

Ji-Jer Huang is now an associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology. He received a B.S. in electrical engineering in 1992 from Feng Chia University. He received his M.S. and Ph.D. in biomedical engineering in 1994 and 2001 from the National Cheng Kung University (NCKU), Tainan, Taiwan. He did research in the field of optoelectronic instruments at the Instrument Technology Research Center, National Applied Research Laboratories, before 2006. His research interests are in electrical impedance imaging, the development of bioelectrical impedance analysis technology, the development of noninvasive biomedical measurement technologies, and the design of MCU/DSP-based biomedical instrument circuits. He now focuses on using AI technology to obtain blood pressure parameters using real-time measurement of physiological signals. He also continues to develop measurement and analysis technology from BIA, EMG, and motion detection to estimate sarcopenia. |

|

Aaron Raymond See was born in Manila, Philippines, and received his B.S. degree in Electronics and Communications Engineering from De La Salle University (DLSU), Manila, in 2006. He obtained his M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical Engineering with a major in Biomedical Engineering from Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology (STUST) in 2010 and 2014, respectively. Subsequently, he did his postdoctoral research in neuroscience at the Brain Research Center, National Tsing Hua University (NTHU), Hsin Chu, Taiwan. He was an associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at STUST and is currently an associate professor in the Department of Electronics Engineering at National Chin- Yi University of Technology (NCUT). His research interests are in assistive device design and development, haptics, machine learning, and biomedical signal processing. |

References

- Zhou, B.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Danaei, G.; Riley, L.M.; Paciorek, C.J.; Stevens, G.A.; Gregg, E.W.; Bennett, J.E.; Solomon, B.; Singleton, R.K.; et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. The lancet 2021, 398, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global report on hypertension: the race against a silent killer, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081062 (accessed December 19, 2024).

- Picone, D.S.; Schultz, M.G.; Otahal, P.; Aakhus, S.; Al-Jumaily, A.M.; Black, J.A.; Bos, W.J.; Chambers, J.B.; Chen, C.H.; Cheng, H.M.; et al. Accuracy of cuff-measured blood pressure: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017, 70, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachuee, M.; Kiani, M.M.; Mohammadzade, H.; Shabany, M. Cuff-less high-accuracy calibration-free blood pressure estimation using pulse transit time. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE international symposium on circuits and systems (ISCAS); IEEE, 2015; pp. 1006–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D.; Ji, Z.; Wang, H. Non-invasive continuous blood pressure estimation from single-channel PPG based on a temporal convolutional network integrated with an attention mechanism. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, I.; Zecchi, M.; Corsini, A.; Marcelli, E.; Cercenelli, L. Technologies for hemodynamic measurements: past, present and future. In Advances in cardiovascular technology; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 515–566.

- Huang, J.J.; Yu, S.I.; Syu, H.Y.; See, A.R. The non-contact heart rate measurement system for monitoring HRV. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE; 2013; pp. 3238–3241. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.J.; Huang, Y.M.; See, A.R. Studying peripheral vascular pulse wave velocity using bio-impedance plethysmography and regression analysis. ECTI Transactions on Computer and Information Technology (ECTI-CIT) 2017, 11, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.J.; Syu, H.Y.; Cai, Z.L.; See, A.R. Development of a long term dynamic blood pressure monitoring system using cuff-less method and pulse transit time. Measurement 2018, 124, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Chen, W.; Lin, C.L.; Juang, C.F.; Wang, J. MLP-BP: A novel framework for cuffless blood pressure measurement with PPG and ECG signals based on MLP-Mixer neural networks. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 73, 103404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidhya, C.; Maithani, Y.; Singh, J.P. Recent advances and challenges in textile electrodes for wearable biopotential signal monitoring: A comprehensive review. Biosensors 2023, 13, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, S.; GholamHosseini, H.; Lowe, A. Non-invasive continuous blood pressure monitoring systems: current and proposed technology issues and challenges. Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine 2020, 43, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachuee, M.; Kiani, M.M.; Mohammadzade, H.; Shabany, M. Cuffless blood pressure estimation algorithms for continuous health-care monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2016, 64, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.; Hsieh, W.T.; Chen, T.P.C. A benchmark for machine-learning based non-invasive blood pressure estimation using photoplethysmogram. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slapničar, G.; Mlakar, N.; Luštrek, M. Blood pressure estimation from photoplethysmogram using a spectro-temporal deep neural network. Sensors 2019, 19, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, M.; Li, K. A multi-type features fusion neural network for blood pressure prediction based on photoplethysmography. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 68, 102772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Scott, D.J.; Villarroel, M.; Clifford, G.D.; Saeed, M.; Mark, R.G. Open-access MIMIC-II database for intensive care research. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE; 2011; pp. 8315–8318. [Google Scholar]

- Kachuee, M.; Kiani, M.M.; Mohammadzade, H.; Shabany, M. Cuff-less blood pressure estimation data set. UCI Machine Learning Repository 2015. [Google Scholar]

- White, W.B.; Berson, A.S.; Robbins, C.; Jamieson, M.J.; Prisant, L.M.; Roccella, E.; Sheps, S.G. National standard for measurement of resting and ambulatory blood pressures with automated sphygmomanometers. Hypertension 1993, 21, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Zhang, Y. Continuous and noninvasive estimation of arterial blood pressure using a photoplethysmographic approach. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (IEEE Cat. No. 03CH37439). IEEE, 2003, Vol. 4, pp. 3153–3156.

- Kurylyak, Y.; Lamonaca, F.; Grimaldi, D. A Neural Network-based method for continuous blood pressure estimation from a PPG signal. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International instrumentation and measurement technology conference (I2MTC). IEEE; 2013; pp. 280–283. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Po, L.M.; Fu, H. Cuffless blood pressure estimation based on photoplethysmography signal and its second derivative. International Journal of Computer Theory and Engineering 2017, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R. Multitask learning. Machine learning 1997, 28, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, A.L.; Amaral, L.A.; Glass, L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Ivanov, P.C.; Mark, R.G.; Mietus, J.E.; Moody, G.B.; Peng, C.K.; Stanley, H.E. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. circulation 2000, 101, e215–e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, G.D.; Scott, D.J.; Villarroel, M.; et al. User guide and documentation for the MIMIC II database. MIMIC-II database version 2009, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, R. On the identification of variances and adaptive Kalman filtering. IEEE Transactions on automatic control 1970, 15, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.S.; Firouzmand, M.; Charmi, M.; Hemmati, M.; Moghadam, M.; Ghorbani, Y. Blood pressure estimation from appropriate and inappropriate PPG signals using A whole-based method. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2019, 47, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python Gaël Varoquaux Bertrand Thirion Vincent Dubourg Alexandre Passos PEDREGOSA, VAROQUAUX, GRAMFORT ET AL. Matthieu Perrot Edouard Duchesnay. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Sun, L.; Yang, F.; Song, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, H. Time Series Data Augmentation for Deep Learning: A Survey. Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.N. A disciplined approach to neural network hyper-parameters: Part 1 – learning rate, batch size, momentum, and weight decay. arXiv:1803.09820 [cs, stat] 2018.

- Pascanu, R.; Mikolov, T.; Bengio, Y. On the difficulty of training recurrent neural networks, 2013.

- Liu, P.; Qiu, X.; Huang, X. Adversarial Multi-task Learning for Text Classification, 2017.

- Smith, L.N. Cyclical Learning Rates for Training Neural Networks, 2017. [CrossRef]

| LOSO Experiments | Systolic Blood Pressure (MAE, mmHg) |

Diastolic Blood Pressure (MAE, mmHg) |

|---|---|---|

| cBP-Tnet (raw PPG only) | 5.72 | 3.09 |

| cBP-Tnet (raw PPG + PPG′) | 5.08 (▾11.24%) | 2.79 (▾9.55%) |

| cBP-Tnet (raw PPG + PPG′ + PPG′′) | 5.00 (▾1.56%) | 2.75 (▾1.43%) |

| cBP-Tnet (raw PPG + PPG′ + PPG′′ + Adaptive Kalman Filter) | 4.95 (▾1.06%) | 2.80 (▾1.56%) |

| cBP-Tnet (raw PPG + PPG′ + PPG′′ + Adaptive Kalman Filter + SBP/DBP Outlier Removal) | 4.81 (▾2.69%) | 2.38 (▾14.84%) |

| cBP-Tnet (raw PPG + PPG′ + PPG′′ + Adaptive Kalman Filter + SBP/DBP Outlier Removal + Signal Synchronization) | 4.80 (▾0.29%) | 2.35 (▾1.30%) |

| cBP-Tnet (raw PPG + PPG′ + PPG′′ + Adaptive Kalman Filter + SBP/DBP Outlier Removal + Signal Synchronization +Data Augmentation) | 4.71 (▾1.85%) | 2.34 (▾0.43%) |

| cBP-Tnet Hyperparameter Tuning/Analysis |

h | N | grad clip |

SBP MAE (mmHg) |

DBP MAE (mmHg) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cBP-Tnet (Base) Model | 128 | 4 | 8 | 0.05 | 4.0 | 4.71 | 2.34 |

| (A) | 64 | 7.25 | 3.72 | ||||

| 256 | 5.03 | 2.55 | |||||

| (B) | 2 | 6.02 | 3.15 | ||||

| 8 | 4.75 | 2.36 | |||||

| (C) | 6 | 4.77 | 2.42 | ||||

| 10 | 4.76 | 2.37 | |||||

| (D) | 0.00 | 4.74 | 2.37 | ||||

| 0.10 | 4.87 | 2.46 | |||||

| (E) | 0.0 | 145.43 | 69.72 | ||||

| 8.0 | 4.75 | 2.36 | |||||

| cBP-Tnet (Extended) Model | 128 | 4 | 8 | 0.05 | 4.0 | 4.32 | 2.18 |

| Related Deep Learning Methods | SBP (MAE, mmHg) | DBP (MAE, mmHg) |

|---|---|---|

| ResNet | 9.43 (r=N/A) | 6.88 (r=N/A) |

| MTFF-ANN | 5.59 (r=0.92) | 3.36 (r=0.86) |

| TCN-CBAM | 5.35 (r=0.80) | 2.12 (r=0.60) |

| cBP-Tnet | 4.32 (r=0.89) | 2.18 (r=0.87) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).