Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The need for an integrated theoretical framework that connects environmental determinants, faculty satisfaction, professional commitment, and institutional outcomes

- The limited attention to bidirectional and reciprocal relationships between these constructs

- Insufficient recognition of important contextual factors, including institutional type, appointment status, career stage, and disciplinary differences

- The lack of validated assessment tools that can be applied across diverse faculty populations

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

2.2. Key Determinants of Faculty Satisfaction and Commitment

2.3. Dimensions of Faculty Satisfaction

2.4. Types and Dimensions of Professional Commitment

2.5. Institutional Outcomes of Faculty Satisfaction and Commitment

2.6. Contextual Variations in Faculty Experiences

2.7. Gaps in Current Literature

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Development

3.2. Assessment Instrument Development

- Item generation based on literature review and qualitative findings

- Expert review by six researchers specializing in faculty development and four academic administrators

- Cognitive interviews with 12 faculty members to assess item clarity and interpretation

- Pilot testing with 78 faculty members across three institutions

- Psychometric analysis including internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha), test-retest reliability, and construct validity

- Final item selection based on factor analysis and item response theory

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Validation of the Integrated Model

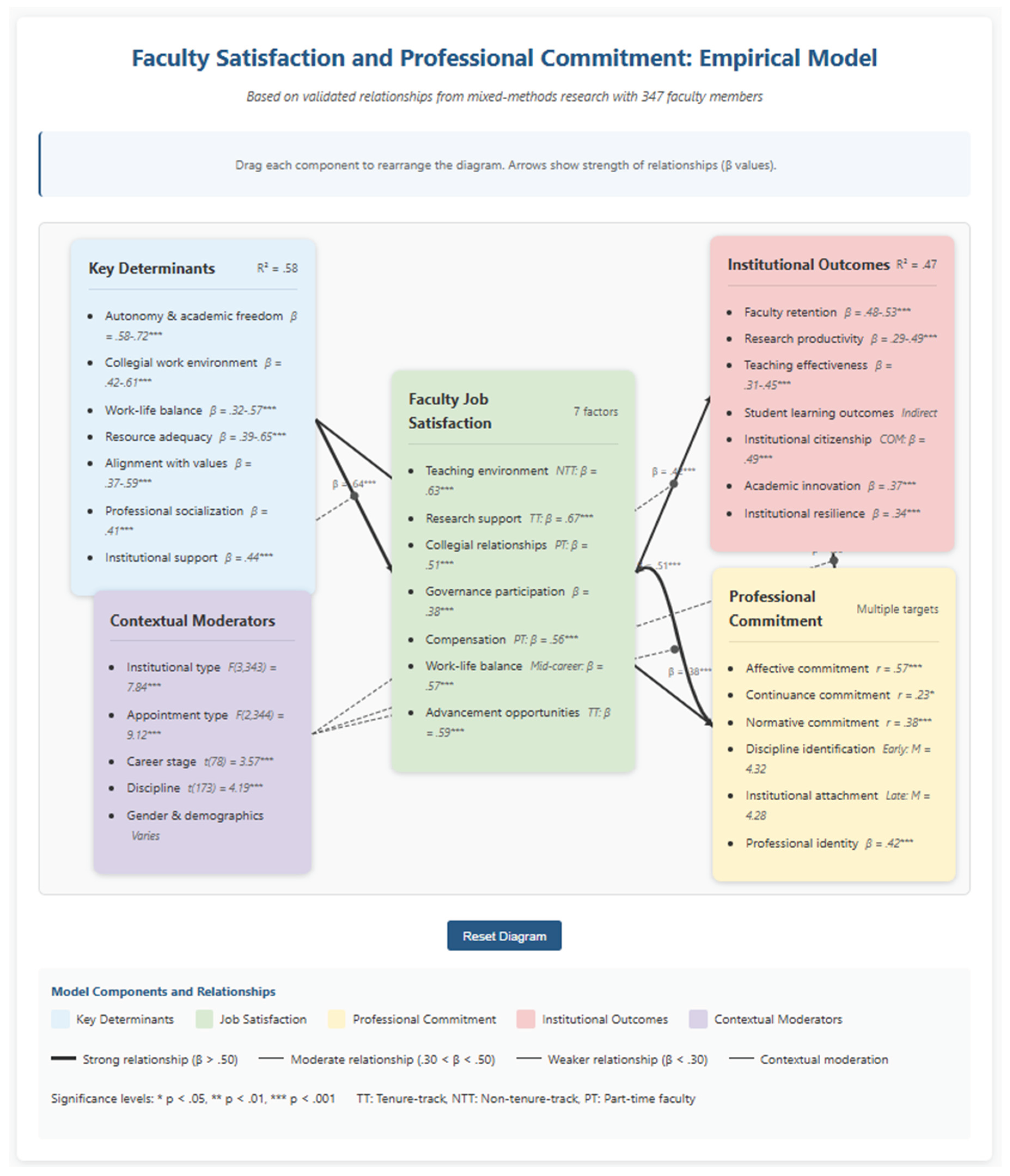

- Autonomy and academic freedom (β = .58-.72***): The strongest predictor across all institutional types, though with varying emphasis on research autonomy at research universities (β = .68***) versus teaching autonomy at teaching-focused institutions (β = .61***).

- Collegial work environment (β = .42-.61***): Particularly important for early-career faculty (β = .61***) compared to mid-career (β = .42***) and late-career faculty (β = .35**).

- Work-life balance (β = .32-.57***): Most influential for mid-career faculty (β = .57***) when family and caregiving responsibilities often peak.

- Resource adequacy (β = .39-.65***): More critical at research universities (β = .65***) than teaching-focused institutions (β = .39***).

- Alignment with values (β = .37-.59***): Especially important for commitment at liberal arts colleges (β = .59***).

- Professional socialization (β = .41***): Consistent across institutional types but with stronger effects for early-career faculty.

- Institutional support (β = .44***): Including recognition, development opportunities, and responsiveness to faculty concerns.

- 2.

- Faculty Job Satisfaction (Green)

- Teaching environment (NTT: β = .63***): Particularly important for non-tenure-track faculty.

- Research support (TT: β = .67***): The strongest predictor for tenure-track faculty at research universities.

- Collegial relationships (PT: β = .51***): Especially important for part-time faculty feeling included.

- Governance participation (β = .38***): Associated with institutional commitment across faculty types.

- Compensation (PT: β = .56***): Particularly important for part-time faculty satisfaction.

- Work-life balance (Mid-career: β = .57***): Most critical for mid-career faculty.

- Advancement opportunities (TT: β = .59***): A strong predictor for tenure-track faculty satisfaction.

- 3.

- Professional Commitment (Yellow)

- Affective commitment (r = .57***): Emotional attachment showing the strongest relationship with discretionary effort and citizenship behaviors.

- Continuance commitment (r = .23*): Awareness of costs associated with leaving, showing the weakest relationship to positive outcomes.

- Normative commitment (r = .38***): Feeling obligated to continue employment.

- Discipline identification (Early: M = 4.32): Strongest among early-career faculty.

- Institutional attachment (Late: M = 4.28): Strongest among late-career faculty.

- Professional identity (β = .42***): Integration of academic role into self-concept.

4.2. Key Determinants and Their Relative Influence

4.3. Dimensions of Faculty Satisfaction

4.4. Professional Commitment Patterns

4.5. Institutional Outcomes

4.6. Contextual Variations

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

- Develop supportive department leadership. Given the strong influence of departmental climate on faculty experiences, institutions should invest in selecting and developing department chairs who can create supportive, inclusive environments. As one faculty participant noted: “My department chair makes all the difference in how I experience my work—they buffer external pressures, recognize achievements, and help navigate challenges.”

- Create transparent workload policies. Clear, equitable policies regarding teaching loads, service expectations, and research support can address important determinants of satisfaction. These policies should acknowledge differences across appointment types while ensuring fairness within categories.

- Implement flexible work arrangements. The increasing importance of work-life balance, particularly following the pandemic, suggests institutions should maintain and expand flexible work options. One administrator in the study observed: “The flexible arrangements we developed during the pandemic have become a recruitment and retention advantage as we’ve maintained some of those options.”

- Align resources with stated priorities. These findings on resource adequacy suggest institutions should ensure alignment between what they claim to value and what they fund. Misalignment between rhetoric and resource allocation emerged as a significant source of faculty dissatisfaction and decreased commitment.

- Establish comprehensive mentoring programs. The particular importance of mentoring for early-career faculty and those from underrepresented groups suggests institutions should develop structured mentoring programs that address both discipline-specific and institutional navigation needs.

- Differentiate support by career stage. These findings on career stage differences suggest the need for tailored faculty development programs that address the evolving concerns of faculty throughout their careers. As one dean explained: “We’ve moved from a one-size-fits-all approach to career-stage appropriate programming, and we’re seeing much better engagement.”

- Create meaningful governance opportunities. The relationship between governance participation and institutional commitment suggests academic leaders should ensure faculty have authentic influence in institutional decision-making, particularly on issues directly affecting academic work.

5.3. Assessment Applications

- Diagnostic assessment. Institutions can use the instrument to identify specific areas of concern within particular departments, colleges, or faculty subgroups, allowing for targeted interventions rather than generic initiatives.

- Program evaluation. The instrument can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of faculty development programs, policy changes, or leadership initiatives in improving satisfaction and commitment over time.

- Comparative benchmarking. With appropriate anonymity protections, institutions can benchmark their results against peer institutions to identify relative strengths and opportunities for improvement.

- Individual faculty development. Individual faculty members can use the self-assessment to reflect on their own experiences and develop personalized strategies for enhancing satisfaction and commitment.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Appendix A. Faculty Satisfaction and Professional Commitment Assessment Instrument

- Instrument Items by Thematic Area

- Section A: Environmental Determinants (12 items)

-

Autonomy and Academic Freedom

- I have sufficient freedom to determine my research agenda.

- I can choose my own teaching approaches and methods.

- I have adequate control over my daily work priorities.

- 2.

-

Collegial Work Environment

- My department has a supportive and collaborative climate.

- My colleagues respect my contributions and perspectives.

- Department leadership is responsive to faculty concerns.

- 3.

-

Work-Life Balance

- My institution supports my efforts to balance professional and personal responsibilities.

- I can maintain a healthy balance between my work and personal life.

- Flexibility in my work arrangements helps me manage competing demands.

- 4.

-

Resource Adequacy

- I have access to the resources needed to perform my work effectively.

- Resources are distributed equitably in my department or unit.

- My institution provides adequate administrative support for my work.

- Section B: Faculty Job Satisfaction (12 items)

-

Teaching Environment

- I am satisfied with my teaching assignments and responsibilities.

- I receive appropriate recognition for my teaching efforts.

- My students are engaged and motivated learners.

- 2.

-

Research Support

- My institution adequately supports my research or scholarly activities.

- I have sufficient time for my research or scholarly pursuits.

- My scholarly achievements are appropriately recognized.

- 3.

-

Collegial Relationships

- I feel a sense of belonging in my department.

- I have productive collaborative relationships with colleagues.

- I can freely share my ideas and concerns with my colleagues.

- 4.

-

Governance and Recognition

- I have meaningful opportunities to participate in departmental decision-making.

- My compensation fairly reflects my contributions and expertise.

- My efforts across all domains (teaching, research, service) are appropriately valued.

- Section C: Professional Commitment (12 items)

-

Affective Commitment

- I feel emotionally attached to my institution.

- I enjoy discussing my institution with people outside it.

- I feel a strong sense of belonging to my academic discipline.

- 2.

-

Continuance Commitment

- Leaving my current institution would require considerable personal sacrifice.

- I have too much invested in my current position to consider changing institutions.

- There are too few alternatives to consider leaving my academic career.

- 3.

-

Normative Commitment

- I feel an obligation to remain at my current institution.

- I feel a responsibility to contribute to my academic discipline.

- I believe in maintaining commitments to institutions even when difficult.

- 4.

-

Professional Identity

- My academic role is a central part of my self-identity.

- I strongly identify with the values of my discipline.

- I see myself primarily as a member of my academic profession.

- Section D: Institutional Outcomes (12 items)

-

Retention Intentions

- I plan to remain at my current institution for the foreseeable future.

- I rarely think about leaving my current position.

- If I could start over, I would choose to work at this institution again.

- 2.

-

Productivity and Effectiveness

- I am productive in my research/scholarly activities.

- I am effective in my teaching responsibilities.

- I make valuable contributions to institutional service and governance.

- 3.

-

Innovation and Growth

- I regularly explore new approaches in my teaching.

- I pursue innovative directions in my research or scholarship.

- I seek out professional development opportunities to enhance my skills.

- 4.

-

Institutional Citizenship

- I willingly take on service responsibilities beyond the minimum expected.

- I advocate for my institution to external stakeholders.

- I help colleagues succeed even when not formally required.

- Comprehensive Assessment Instructions

- Purpose and Use

- Individual faculty members with insights into their professional experiences and potential areas for enhancing satisfaction and commitment.

- Academic leaders with aggregated data to identify institutional strengths and opportunities for improving faculty work environments.

- Researchers with a validated tool for studying faculty experiences across different institutional contexts.

- Administration Guidelines

- Self-Assessment Instructions for Faculty

- Response Scale:

- Demographic Information:

- Institution type (Research university, liberal arts college, comprehensive university, community college, other)

- Appointment type (Tenure-track, full-time non-tenure-track, part-time)

- Career stage (Early: 0-7 years, Mid: 8-20 years, Late: 21+ years)

- Primary disciplinary area (Humanities, Social Sciences, STEM, Professional/Applied, Other)

- Administrative role (Yes/No)

- Gender (Optional)

- Race/Ethnicity (Optional)

- Institutional Administration Guidelines

- Timing: Administer the assessment during a typical academic period, avoiding unusual stress points (e.g., beginning of term rather than finals week).

- Communication: Clearly communicate the purpose of the assessment, how data will be used, and confidentiality protections.

- Sampling: Aim for representative participation across departments, appointment types, and career stages. Consider stratified sampling if complete participation is not feasible.

- Confidentiality: Ensure demographic categories are broad enough that individuals cannot be identified when results are disaggregated.

- Frequency: Consider annual or biennial administration to track changes over time.

- Scoring and Interpretation

- Individual Scoring

- Calculate average scores for each of the four main sections (A-D).

- Calculate subscale scores within each section (e.g., Autonomy, Collegial Environment, etc.).

-

Compare your scores to the following interpretive ranges:

- 4.0-5.0: Strong/High level

- 3.0-3.99: Moderate level

- 2.0-2.99: Low level

- 1.0-1.99: Very low level

- Individual Interpretation Guidelines

- Environmental Determinants (Section A):

- High scores (4.0-5.0) indicate a supportive work environment with adequate resources, autonomy, collegiality, and work-life balance.

- Low scores (below 3.0) suggest environmental constraints that may limit professional effectiveness and satisfaction.

- Pay particular attention to subscale variations, as specific environmental factors may require different strategies for improvement.

- Job Satisfaction (Section B):

- High scores reflect contentment with various aspects of your academic role.

- Low scores may indicate areas where career adjustments or institutional advocacy could improve your experience.

- Consider how your satisfaction profile aligns with your career priorities and values.

- Professional Commitment (Section C):

- Examine the balance between different types of commitment (affective, continuance, normative) and commitment targets (institution, discipline, profession).

- Strong affective commitment (wanting to stay) generally predicts more positive outcomes than continuance commitment (needing to stay).

- Consider how your commitment profile may influence career decisions and institutional engagement.

- Institutional Outcomes (Section D):

- These scores reflect the consequences of your satisfaction and commitment levels.

- Low scores, particularly in retention intentions, may signal the need for career reflection or environment changes.

- High variability across outcome subscales (e.g., high productivity but low citizenship) may indicate strategic adaptation to your environment.

- Institutional Analysis Guidelines

- Overall Patterns: Calculate institutional averages for each section and subscale.

-

Comparative Analysis: Examine differences by:

- Department or college

- Appointment type

- Career stage

- Discipline

- Demographics (when sample size ensures confidentiality)

- 3.

- Relationship Analysis: Examine correlations between environmental factors, satisfaction, commitment, and outcomes to identify priority areas for intervention.

- 4.

- Benchmarking: If available, compare results to national norms or peer institutions.

- 5.

- Longitudinal Tracking: Monitor changes over time, particularly following interventions.

- Using Assessment Results

- For Individual Faculty

- 1.

- Identify Strengths and Challenges: Review your profile to identify areas of strength and potential concern.

- 2.

-

Develop Personal Strategies: Based on your scores, consider:

- For low environmental scores: Strategies to advocate for improved conditions or to create microenvironments that better support your work

- For low satisfaction: Potential adjustments to workload, focus, or approach

- For commitment imbalances: Reflection on career alignment and priorities

- 3.

- Set Professional Development Goals: Use results to inform specific professional development objectives.

- 4.

- Track Changes: Reassess periodically to monitor progress and adapt strategies.

- For Academic Leaders

-

Prioritize Interventions: Focus on factors with:

- Low overall scores

- Strong correlations with important outcomes

- Significant disparities across faculty groups

- 2.

-

Develop Targeted Initiatives: Create specific programs addressing identified needs, such as:

- Mentoring programs for early-career faculty

- Work-life policies for mid-career faculty

- Leadership opportunities for late-career faculty

- Resource equity initiatives for underrepresented groups

- 3.

- Engage Faculty in Solutions: Share aggregated findings and involve faculty in developing improvement strategies.

- 4.

- Evaluate Effectiveness: Reassess after implementing changes to measure impact.

- 5.

- Integrate with Strategic Planning: Use findings to inform broader institutional planning and resource allocation.

- Technical Notes

- Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha): .82 to .91 for subscales

- Test-retest reliability: .78 to .86

- Convergent validity with established measures: r = .67 to .79

- Discriminant validity: Confirmed through factor analysis

- Criterion validity: Significant correlations with objective outcome measures

References

- Austin, A.E. Preparing the Next Generation of Faculty: Graduate School as Socialization to the Academic Career. J. High. Educ. 2002, 73, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A.J. The socialization of future faculty: Implications for higher education. Metropolitan Universities 2011, 22, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.G.; Lunceford, C.J.; E Vanderlinden, K. Faculty in the Middle Years: Illuminating an Overlooked Phase of Academic Life. Rev. High. Educ. 2005, 29, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, P.J.; Kyvik, S. Academic work from a comparative perspective: a survey of faculty working time across 13 countries. High. Educ. 2011, 63, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, R.T.; Lawrence, J.H. Faculty at work: Motivation, expectation, satisfaction; Johns Hopkins University Press: 1995.

- Bozeman, B.; Gaughan, M. Job satisfaction among university faculty: Individual, work, and institutional determinants. The Journal of Higher Education 2011, 82, 154–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.R. The academic life: Small worlds, different worlds; Princeton University Press: 1987.

- Daly, C.J.; Dee, J.R. Greener pastures: Faculty turnover intent in urban public universities. The Journal of Higher Education 2006, 77, 776–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denson, N.; Szelényi, K.; Bresonis, K. Correlates of Work-Life Balance for Faculty Across Racial/Ethnic Groups. Res. High. Educ. 2018, 59, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, R.G. Don't Blame Faculty for High Tuition: The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession 2003-04. Academe 2004, 90, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, D.E.; Hyle, A.E. Assistant to “full”: Rank and the development of expertise. Teachers College Record 2009, 111, 443–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.F.; Mohapatra, S. Social-organizational characteristics of work and publication productivity among academic scientists in doctoral-granting departments. The Journal of Higher Education 2007, 78, 542–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gappa, J.M. , Austin, A.E.; Trice, A.G. In Rethinking faculty work: Higher education’s strategic imperative; Jossey-Bass, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn, L.S. Conceptualizing Faculty Job Satisfaction: Components, Theories, and Outcomes. New Dir. Institutional Res. 2000, 2000, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsrud, L.K.; Rosser, V.J. Faculty Members' Morale and Their Intention to Leave: A Multilevel Explanation. J. High. Educ. 2002, 73, 518–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezar, A.; Sam, C. Understanding the new majority of non-tenure-track faculty in higher education: Demographics, experiences, and plans of action. ASHE Higher Education Report 2010, 36, 1–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, J.H.; Celis, S.; Ott, M. Is the Tenure Process Fair? What Faculty Think. J. High. Educ. 2014, 85, 155–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.A. , Wolfinger, N.H.; Goulden, M. Do babies matter? Gender and family in the ivory tower; Rutgers University Press:, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T. , Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Y.; Finaly-Neumann, E. The reward-support framework and faculty commitment to their university. Res. High. Educ. 1990, 31, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Meara, K. A career with a view: Agentic perspectives of women faculty. The Journal of Higher Education 2015, 86, 331–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Meara, K.; Bloomgarden, A. The pursuit of prestige: The experience of institutional striving from a faculty perspective. The Journal of the Professoriate 2011, 4, 39–73. [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara, K.; Lennartz, C.J.; Kuvaeva, A.; Jaeger, A.; Misra, J. Department Conditions and Practices Associated with Faculty Workload Satisfaction and Perceptions of Equity. J. High. Educ. 2019, 90, 744–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponjuan, L. , Conley, V.M.; Trower, C. Career stage differences in pre-tenure track faculty perceptions of professional and personal relationships with colleagues. The Journal of Higher Education 2011, 82, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, V.J. Faculty Members' Intentions to Leave: A National Study on Their Worklife and Satisfaction. Res. High. Educ. 2004, 45, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabharwal, M.; Corley, E.A. Faculty job satisfaction across gender and discipline. Soc. Sci. J. 2009, 46, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terosky, A.L.; Gonzales, L.D. Re-envisioned Contributions: Experiences of Faculty Employed at Institutional Types that Differ from their Original Aspirations. Rev. High. Educ. 2016, 39, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigwell, K.; Prosser, M. Development and Use of the Approaches to Teaching Inventory. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbach, P.D.; Wawrzynski, M.R. Faculty do Matter: The Role of College Faculty in Student Learning and Engagement. Res. High. Educ. 2005, 46, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltman, J. , Bergom, I., Hollenshead, C., Miller, J.; August, L. Factors contributing to job satisfaction and dissatisfaction among non-tenure-track faculty. The Journal of Higher Education 2012, 83, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, K.L. Research productivity of foreign- and US-born faculty: differences by time on task. High. Educ. 2012, 64, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, K.L. The working environment matters: Faculty member job satisfaction by institution type. Research in Higher Education 2018, 59, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).