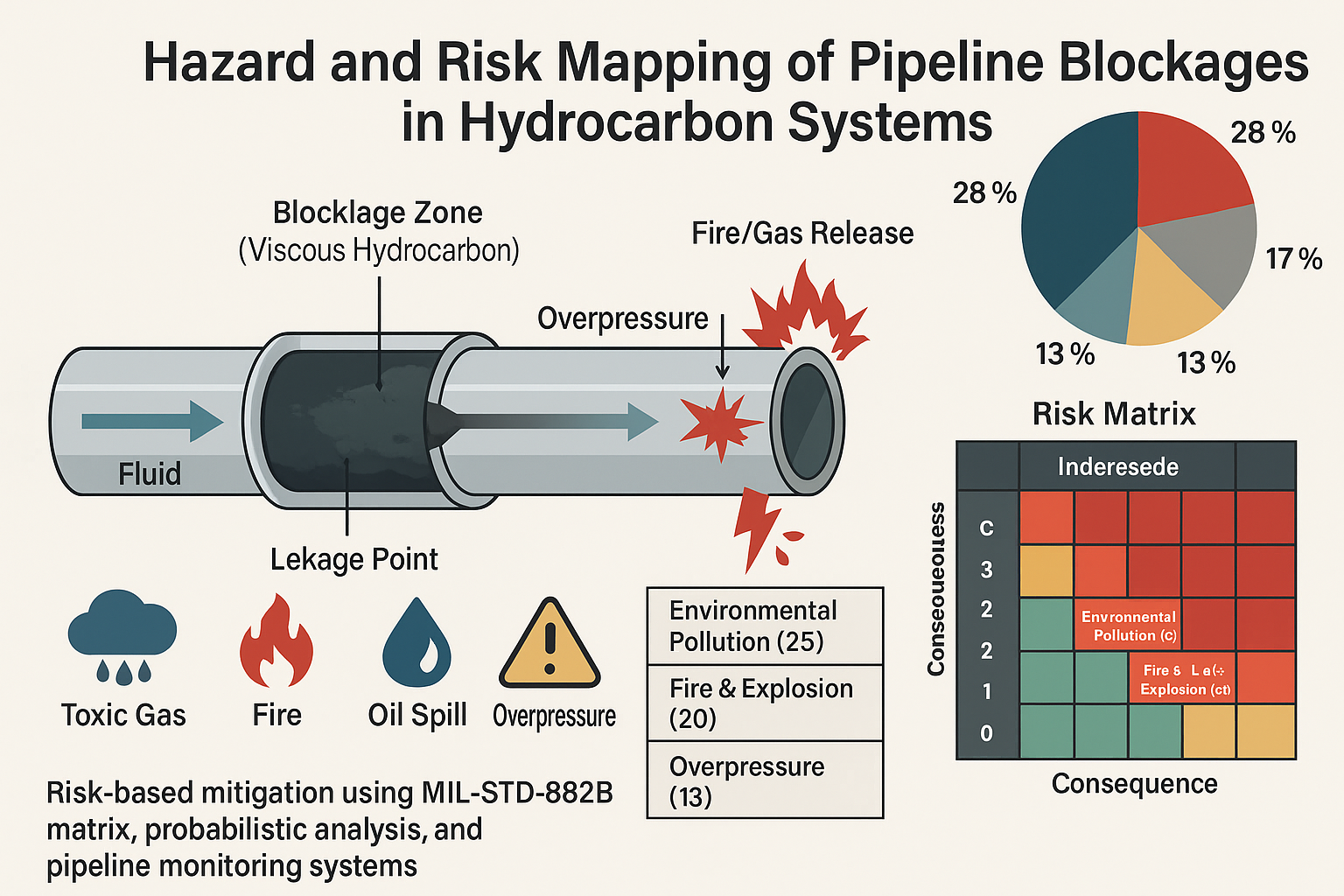

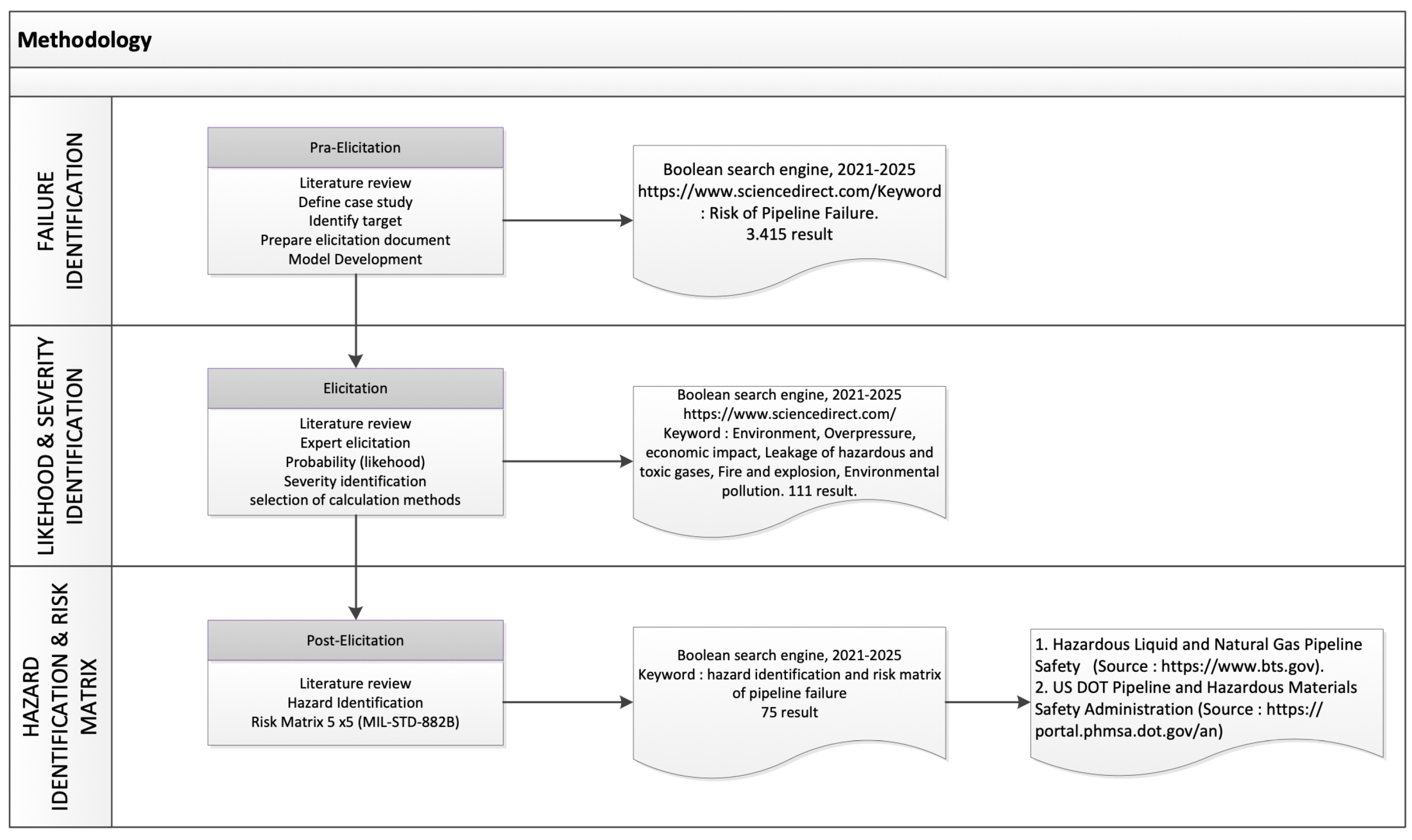

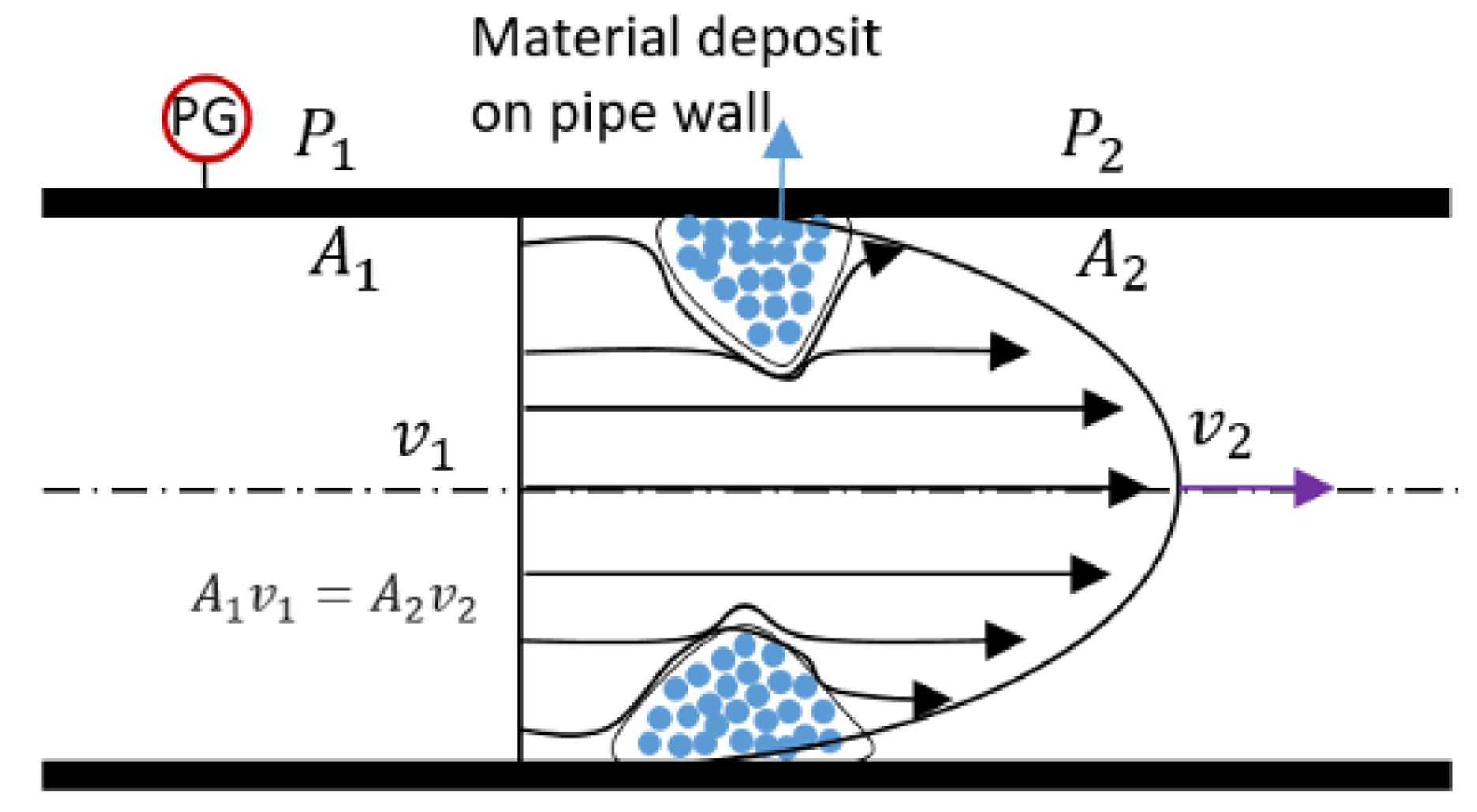

3.1. Causes of Pipe Blockage

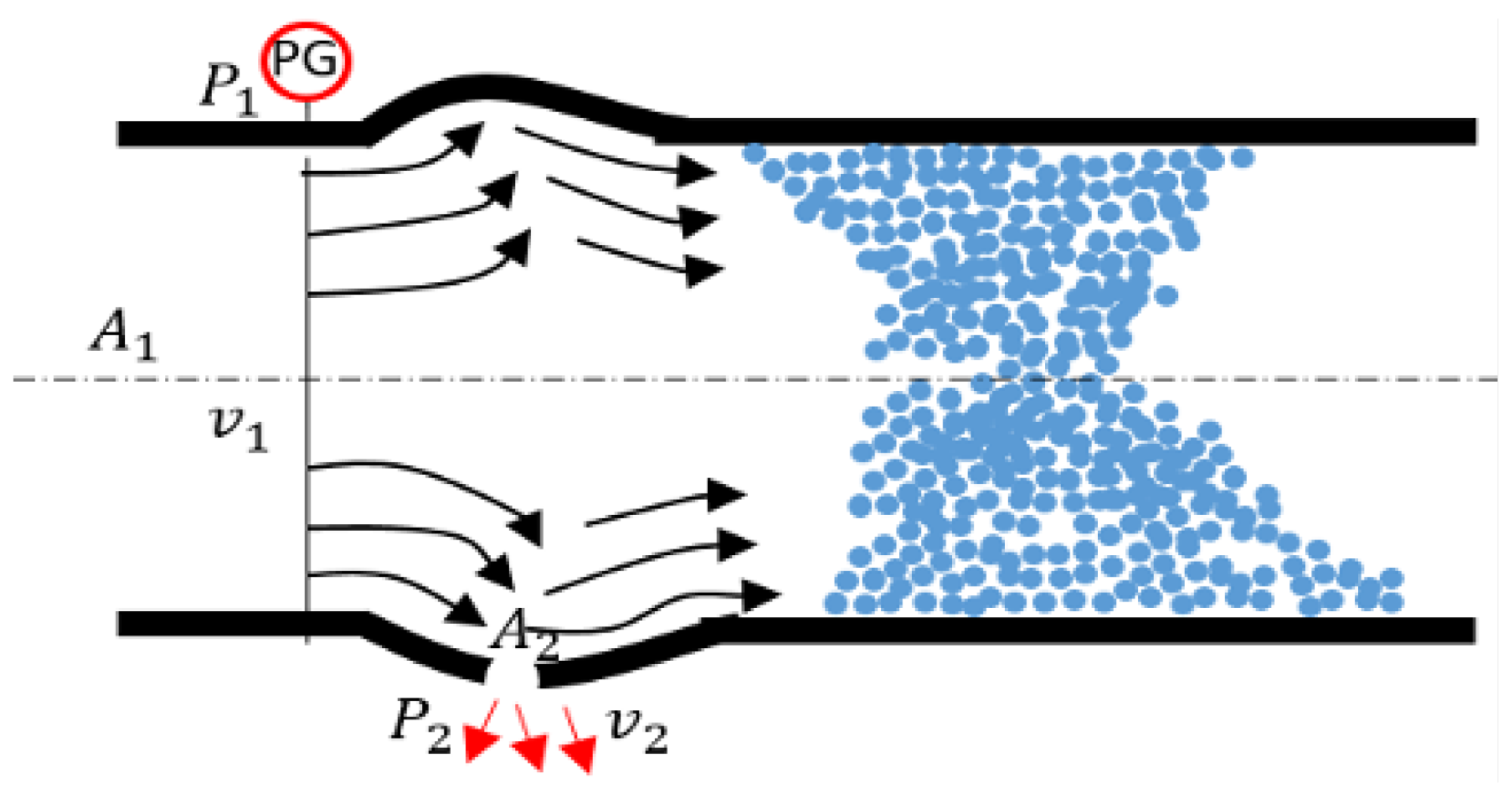

Under normal flow conditions through a pipe network, Bernoulli’s law equation applies. In ideal fluid flow (without friction and no energy loss), fluid pressure, kinetic energy, and potential energy remain constant along the flow line [

43], as shown in

Figure 3:

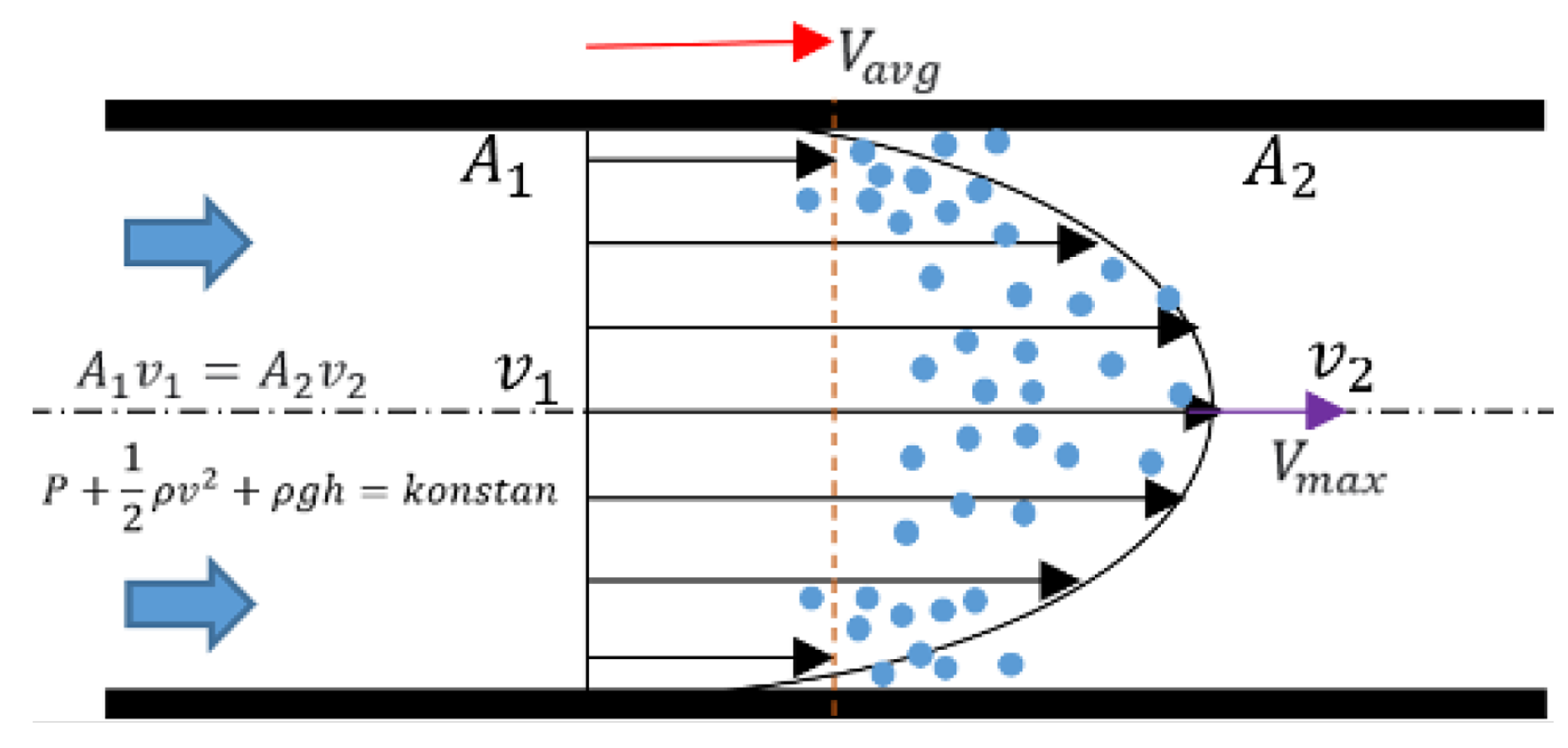

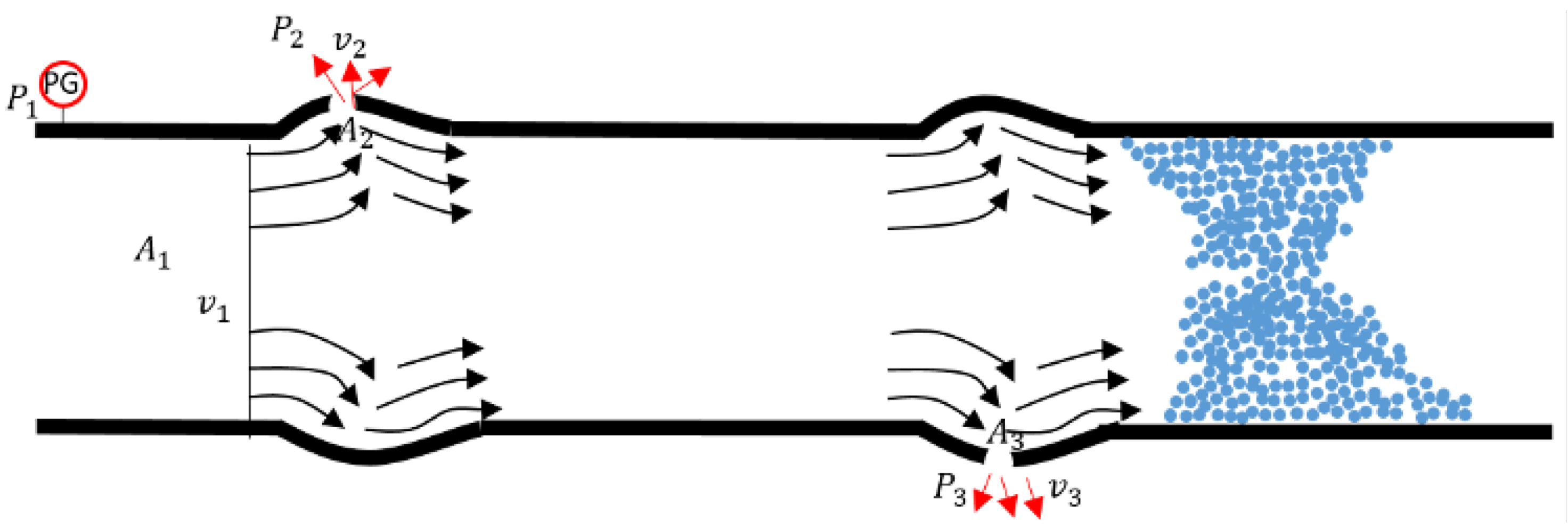

The blockage of the pipe diameter begins with the adhesion of material deposits on the pipe wall, which gradually causes a narrowing of the pipe cross-section (

Figure 4). Finally, under certain conditions, the pipe hole through which this fluid passes becomes closed or blocked [

44,

45].

When there is a build-up of deposit material on the pipe wall, there will be a narrowing of the pipe cross-sectional diameter (), which will cause an increase in fluid velocity (), and there will also be a pressure drop at the downstream position ().

This attached material is a hydrocarbon compound, generally composed of 1-4% sulphur and nitrogen, oxygen, metals, salts, 13% hydrogen, and 85.5% carbon. Hydrocarbons with an API specific gravity between

have the characteristic of freezing on the pipe wall at the pour point temperature [

46,

47].

Hydrocarbon complex mixtures are formed from several chemical compound structures consisting of aromatics, iso-paraffins, naphtha, sulphur compounds, nitrogen, paraffin, asphalt, and oxygen. This chemical mixture is grouped based on solubility and polarity, which results in viscosity properties. The higher the viscosity, the greater the flow resistance and the slower the speed of flow. The higher the viscosity, the greater the resistance to flow, and the slower the speed of the hydrocarbons flowing (velocity), where these viscous properties come from the mixture that exists in hydrocarbons, especially paraffin wax and asphalt [

48,

49].

The American Petroleum Institute standard (API gravity unit) is a unit for the specific gravity of crude oil. API gravity below

or greater than 1000

is considered extra heavy oil, API gravity from

to

or 920 kg/m3 to 1000 kg/m3 is in the heavy category, and API greater than

or less than 870

is light oil. Viscosity is the resistance of a fluid to flow or deform, also known as a measure of fluid thickness, measured in centipoise units. The higher the centipoise number, the higher the fluid viscosity [

50].

Many mixtures of chemical structures form hydrocarbon complexes, which are classified according to solubility and polarity, contributing to viscosity properties. The higher the viscosity, the greater the flow resistance and the slower the speed of hydrocarbons flowing (velocity). These viscous properties come from mixtures that exist in hydrocarbons such as paraffin, iso-paraffin, asphalt, sulphur, and others [

51].

Paraffin wax is a compound that sticks to the pipe wall and forms wax crystals when the temperature is below its cloud point at 14.2 °C–37.83 °C, commonly referred to as the Wax Appearance Temperature (WAT) [

51,

52].

Hydrocarbons with asphalt and wax content are usually difficult to flow through pipes because the high viscosity causes congealing and sticking to the pipe wall. Gradually, the cross-sectional diameter of the pipe through which the fluid flows shrink and closes (blockage), which is a very serious problem in hydrocarbon distribution operations [

52].

The problem of wax deposition has been studied by modelling using equations from the disciplines of thermodynamics, heat transfer, mass transfer, fluid dynamics, and Petro-chemistry to design piping systems and maintenance strategies. However, it is very difficult to measure the rate of deposit formation, determine the point where deposits occur, the number of deposits formed, and the area and thickness of the deposits.

3.2. Risk of Pipe Blockage

Deposits adhering to the pipe wall will reduce the diameter of the pipe cross-section flow. At one point, this pipe diameter hole will suddenly close (totally blocked) without knowing the position, amount, and area of the blockage (

Figure 6). The closure of this fluid flow will cause an increase in pumping pressure at the upstream position, which will be greater than the maximum allowable working pressure, causing the weakest part of the pipe or the smallest thickness to be penetrated by its working pressure, resulting in leakage (

Figure 7) [

53].

The number of leakage points due to this blockage in complex and long pipelines will be difficult to determine quickly and will take a long time to address (

Figure 8). Until the point of blockage is resolved, the pressure increase cannot be controlled, and the potential for leakage can occur at any time along the complex pipeline network.

This leak can occur suddenly without being noticed along the pipe network, where the leak flow rate and the fluid pressure that comes out will be very difficult to handle quickly. The anomaly that occurs should start from an abnormal increase in pressure at the upstream position, a large pressure drops at the downstream position of the pipe, and an unnatural temperature loss. This anomaly will increase in intensity over time, and if ignored without corrective action or continued operation under normal conditions, it will increase the probability of pipe damage.

Calculation of the probability of failure and damage to the pipe and assessment of the consequences of the incident are key elements of the risk assessment of pipe blockages. The assessment of the risk of pipe blockages can be started by determining the rate of sediment formation and the damage mechanisms that can occur as a result of this sedimentation, which is assessed from the beginning until the estimated failure that causes leakage.

The probabilistic method is an assessment that is estimated to determine the possibility of failure, where the limit state approach is also applied so that the assessment results are more precise and not confusing. This limit state is influenced by inherent variables that are random and uncertain but can be modelled with probability theory. Risk assessment based on the probability of occurrence in the form of the release of toxic and hazardous gases that can cause fires, explosions, and respiratory disorders can be regulated based on the characteristics of the mixture of hydrocarbons that pass through the piping system.

The assessment of the risk of environmental pollution is based on the geographical risk passed by the pipeline network, which can be in the form of forests, rivers, seas, gardens, and other environmental ecosystems. The more difficult the geographical topography and the larger the area of the complex area with plant ecology and animal biota, the greater the risk will be assessed.

From the company’s perspective, it is used to assess the social risks caused by the assessment by calculating the impact on the health and activities of the surrounding community. If there are casualties, there is a non-linear relationship between the risk and the number of fatalities that can be calculated as a high level of social disruption risk that can affect the company’s reputation, the potential for large compensation payments for death and health recovery, termination of operating permits, and company closure by the government.

3.3. Identifying Pipe Blockage Hazard

Several hazards can be identified in the case of an unmonitored pipe blockage, namely the occurrence of overpressure upstream of the pipe, which will cause the pipe to rupture because it is unable to withstand the pressure (operating pressure above the maximum allowable working pressure).

Leaks that occur can result in oil spills, toxic gases, and flammable gases that can cause hazardous exposure to the surrounding environment and community. If not immediately isolated, they can cause environmental pollution due to crude oil seeping into the ground (oil spill) or polluting water bodies, endangering local ecosystems and requiring high costs for the clean-up process. Toxic gas leaks cause respiratory problems, such as hydrogen sulphide () gas, which can cause asphyxiation (lack of oxygen) and death of plants within a certain radius. The release of flammable gases causes fires and explosions that endanger lives and property. In addition, there is a risk that the company will experience a potential loss of production due to unplanned shutdowns to handle leaks.

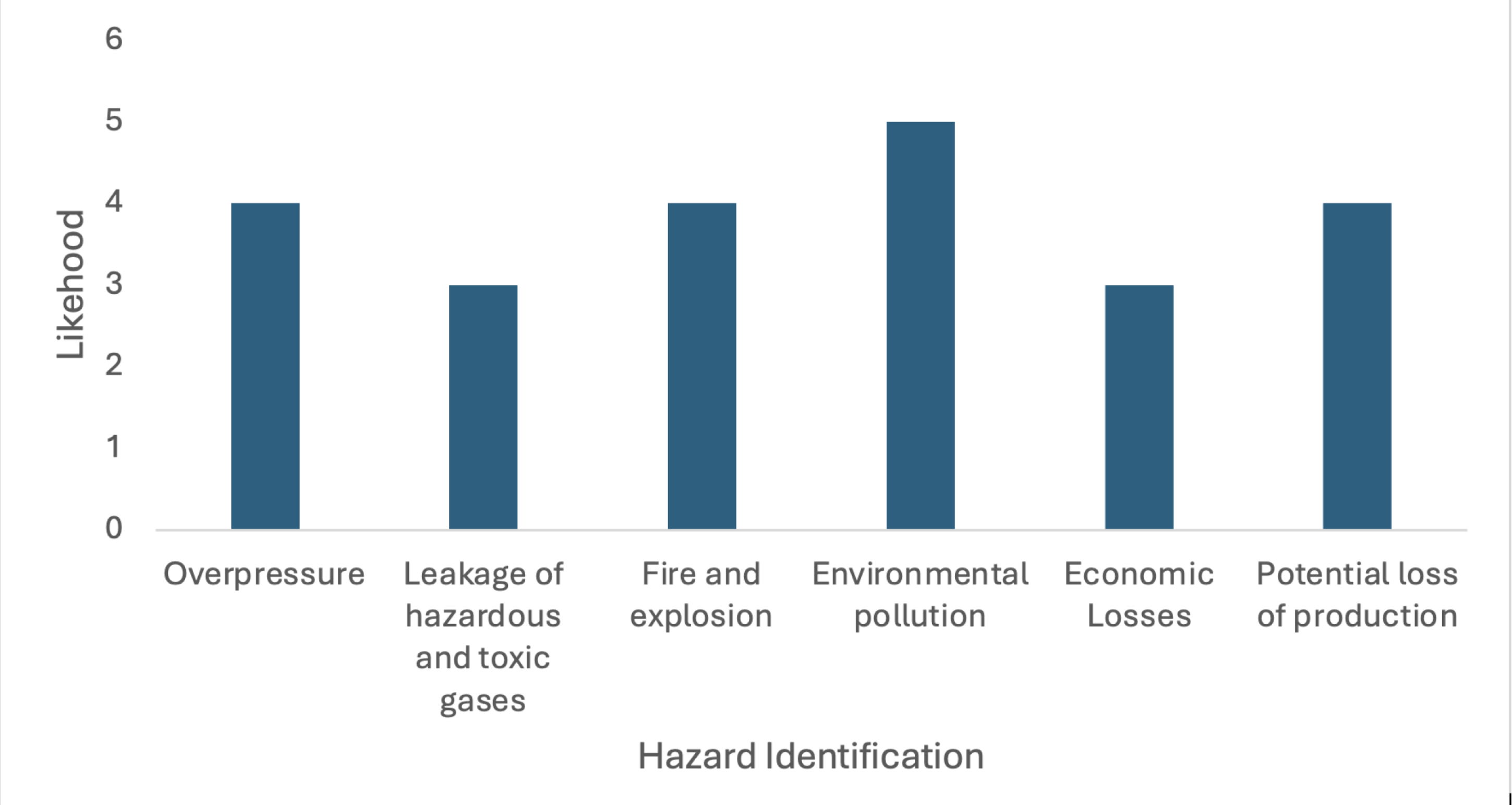

The probability value of the possibility of the identified risk occurring can be used to assess the likelihood of the risk occurring according to

Table 4 as follows:

Environmental damage becomes a certainty that occurs in the future if the blockage causes a leak, where the possibility of occurring is more than 80%, while the danger of overpressure will tend to increase from 50% to 80%, the same as the danger of fire and explosion and the potential for loss of production. The danger of hazardous and toxic gases and respiratory disorders will occur under certain conditions, such as leaks at higher ambient temperatures and wind flow in all directions, so it is only worth 20%–50%.

From

Figure 9, it is very clear that environmental pollution has the greatest possibility of occurring compared to other potential hazards. This is because no matter how much crude oil is spilled, it will always result in environmental pollution on land and in water, where the only difference is the area contaminated by the volume of crude oil spilled. The dangers of overpressure, fire, explosion, and the potential for production loss are at the same probability value because pipeline blockages that can be identified too late can be minimized by stopping production and closing the flow in the blocked pipeline.

Meanwhile, the severity level is calculated using

Table 2 severity assessment parameters, as shown in the following

Table 5:

Meanwhile, hazardous and toxic gas leaks that can cause death depend on the chemical mixture contained in hydrocarbons, such as light hydrocarbon gases (methane, ethane, propane, and butane), which, in addition to causing dizziness, nausea, and hallucinations, can also form explosive mixtures in the air. Hydrogen sulphide () content at high doses can cause fainting, respiratory paralysis, and death. Hydrocarbons containing carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (), nitrogen oxide (), and sulphur oxide () can irritate the respiratory tract, causing headaches and respiratory disorders. At high concentrations, they can cause respiratory arrest.

The severity of the hazards is assessed based on the aspects of health and safety, environmental impact, reputation, and asset damage. From the health and safety aspect, all hazards except the potential loss of production are rated five because they can cause more than one fatality and impact the environment, such as causing smoke from fires and spreading fire to the surrounding area.

For the environmental impact aspect, hazardous and flammable gas leaks and environmental pollution are rated five because they will cause an oil spill of more than 500 barrels, causing permanent environmental damage. As a result, the company must provide special compensation to the affected community (economic losses). For this incident, a special team is needed to handle it. In the aspect of the company’s reputation, hazardous and toxic gas, fire and explosion, and environmental pollution are rated five because they will have an impact on reputation damage due to negative news from national and international media, disrupting society and violating the law, resulting in demands for rehabilitation and even demands to stop or close the operating permit.

For aspects that impact the environment, toxic and hazardous gas leaks, environmental pollution, and respiratory disorders are rated 5 because the hazards that occur require a very long time for the recovery process. From the aspect of company reputation, the severity of toxic and hazardous gas leaks, fire, and environmental contamination are also rated at the maximum because damage to this reputation can result in the termination of management permits by the government or the termination of hydrocarbon sales and purchase contracts with partners, thus affecting the company’s finances. As for the aspect of asset damage, fire and explosion hazards and environmental pollution are rated 5 because these hazards can cause the loss and damage of assets used by the company to produce hydrocarbons.

Aspects of asset damage, fire, and explosion hazards, and environmental damage are rated five because they will likely cause losses of more than USD 20,000,000, a decrease of more than 75% in daily production, and a stoppage of production for more than 30 days. Of all the aspects identified and assessed, the highest severity level is the leakage of hazardous and toxic gases, fire and explosion, and environmental damage. From the possible risks and severity, the risk levels can be identified as follows:

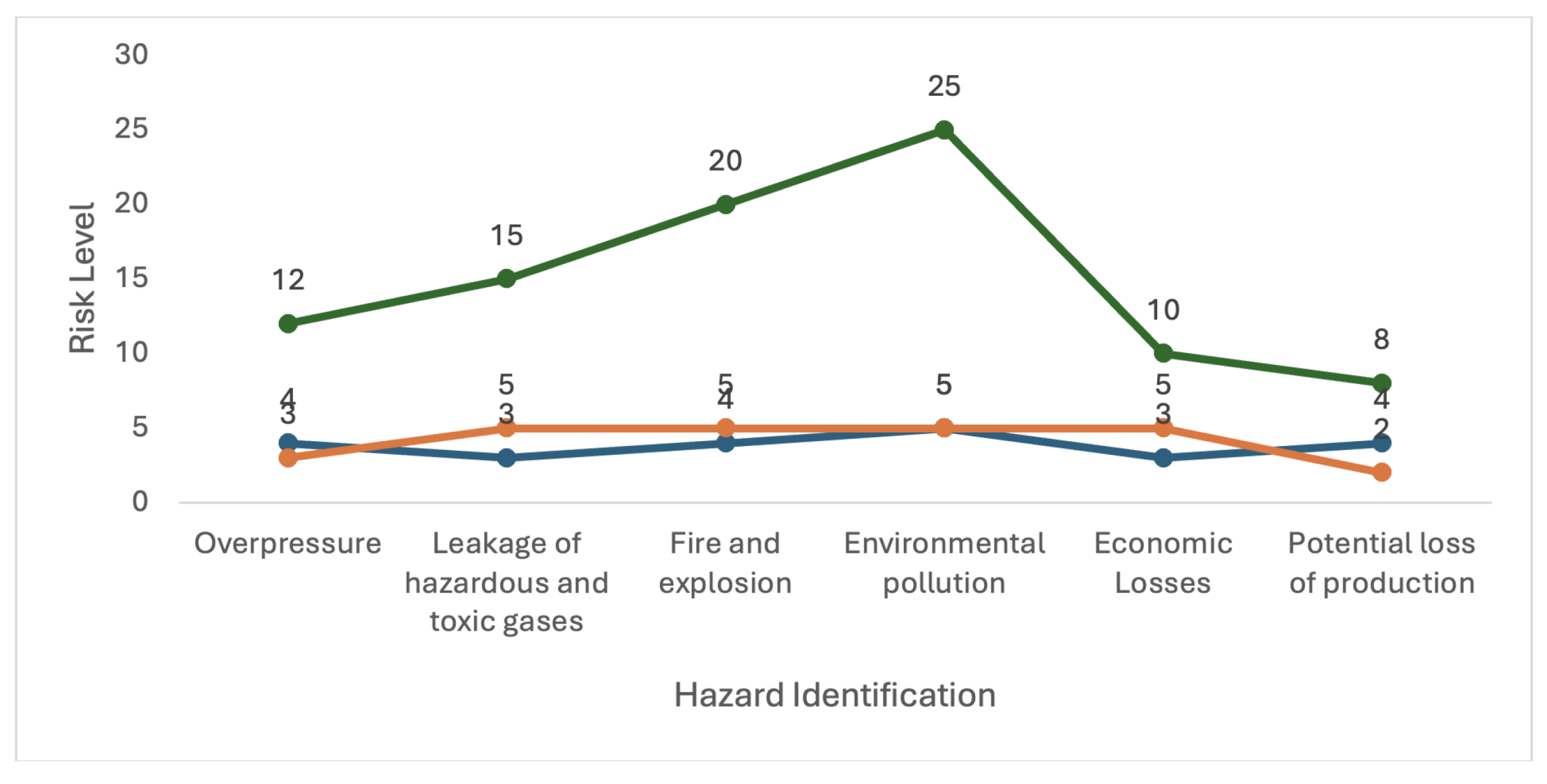

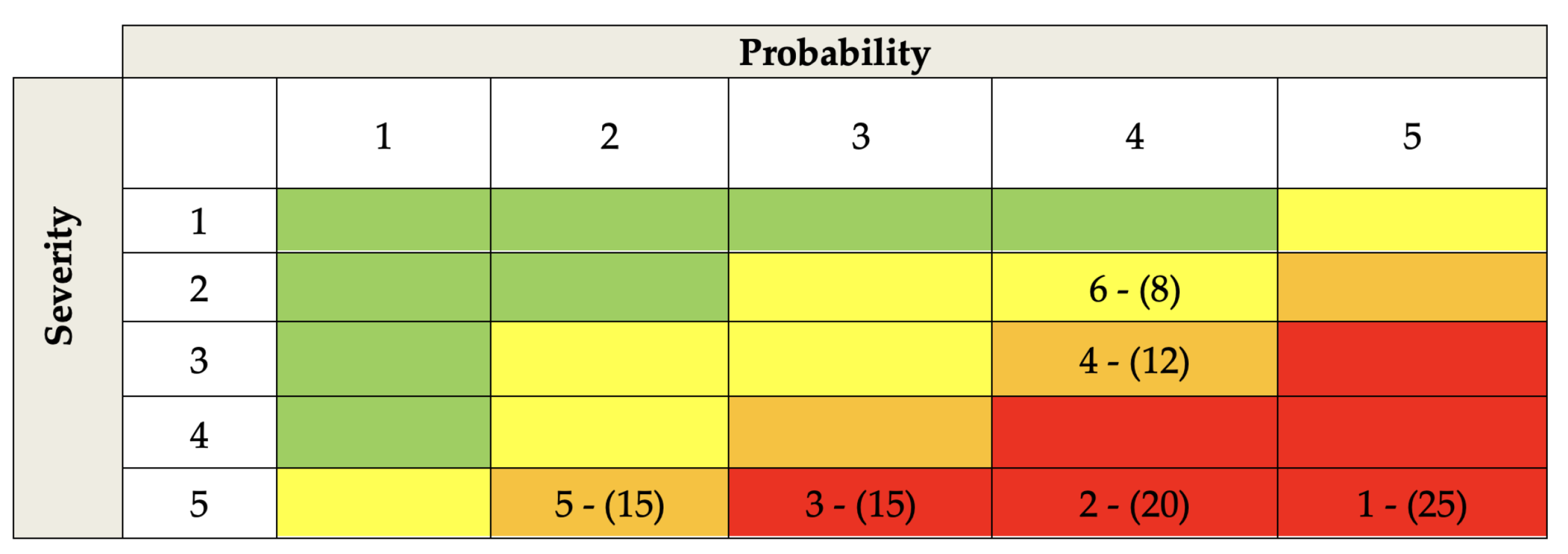

The risk level is then calculated by identifying the possibility and severity (

Table 6). The highest risk level is 25 for environmental pollution, fire, and explosion, and hazardous and toxic gases. This risk is unacceptable, and a control action plan must be carried out immediately before a dangerous event occurs. If it occurs, action must be taken immediately by involving all stakeholders and rapid response teams from within and outside the company. Improvement efforts must also align with improvements in administrative documents, such as improvements to safety and environmental designs, procedures, and documents, and changes to critical management.

From

Figure 11, it is known that the probability of occurrence is inversely proportional to the severity of each identified hazard (overpressure, hazardous and toxic gases, fire and explosion, environmental pollution, economic loss, and loss of production). Environmental pollution is very likely to occur with a high level of severity, almost the same as fire and explosion. While the danger of hazardous and toxic gases is still influenced by the composition of hydrocarbons, even though the severity level is at its maximum value, the probability of occurrence is smaller than that of fire and explosion. Loss of production will occur but is considered low for the severity level because it is considered that loss of production is only a delay in the hydrocarbons that will be produced. From the possible risk levels that have been calculated from the probability and severity levels, the risk levels can then be plotted on the risk matrix as follows:

The risk matrix shows that the red risks are environmental pollution, fire and explosion, and leakage of hazardous and toxic gases. From this risk matrix, the company can identify and evaluate risks in various modes of operating conditions and equipment so that risks can be managed and mapped in a structured manner by preparing all company resources to prevent the risk of danger from occurring. This includes conducting administrative controls and periodic checks, updating procedures periodically, finding the right method to avoid blockage or methods for finding blockage points, and complying with applicable standards and regulations. All preventive measures are arranged based on priorities and hazards that have been identified. From the matrix description, appropriate and fast actions can be decided immediately with effective and efficient resource management, periodic risk monitoring and evaluation, and socialization to improve a good culture for managing risks so that they do not become hazards that threaten the environment’s and the company’s sustainability.

This is in line with the costs that have been incurred for recovery in several cases that have occurred, based on the order of severity and risk level, as follows:

The oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico damaged the marine and coastal ecosystem and ecology due to the spill of 4 million barrels of oil for 3 months, which required a cost of USD 65 billion for handling and recovery [

54]. The Piper Alpha fire and explosion in northeast Scotland caused 167 fatalities, which required a cost of USD 3.4 billion for repairs and compensation [

55]. In the Bhopal accident case in India, toxic and hazardous gases caused thousands of fatalities and had long-term impacts on health and the environment, with recovery and compensation costs of USD 3 billion [

56]. The overpressure incident in an old pipe, which caused major damage to surrounding settlements and claimed lives, occurred in the PG&E gas pipeline in the San Bruno area [

16]. Economic losses of USD 54 billion occurred in the case of crude oil pipeline blockage in Nigeria, as well as the incident at Lake Nyos in Cameroon, Central Africa, which claimed many lives due to respiratory problems [

57]. Finally, in the case of the Nord Stream Gas Pipeline, production losses amounted to 478,000 tons of

[

14].

3.4. Risk Mitigation

In order to prevent disasters caused by pipeline spills, risk mitigation is carried out as an effort to reduce the risk impact of this event, which is detrimental to the global environment and society. Mitigating the risk of this incident starts from the planning and design of the pipe, which must be calculated based on environmental conditions, fluid flow, nature, and characteristics of the fluid passing through it. This opinion was also conveyed by Palmer-Jones et al., 2006 [

58] at the International Pipeline Conference in Canada, where pipe design, operation, inspection, and repair must be considered in the pipeline risk management system.

Strengthening the pipe layer with anti-corrosion materials, equipping the pipe with heaters and insulation, and equipping it with chemical injector facilities are the best choices for piping systems passing through disaster-prone and densely populated routes. Price et al. also conveyed the same opinion at the 2007 International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference [

59] for the use of anti-corrosion insulation on offshore pipelines.

The combination of advanced technology, rapid response, and careful planning is joint mitigation that must be prepared as a preventive measure, detection, and rapid action so that the impacts can be minimized. This is in accordance with the opinion of Tatiparthi et al., 2025, who suggested the use of Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors to detect blockages in real-time [

60]. However, this combination will only be successful if supported by comprehensive and accurate field data, resulting in more sophisticated technological improvements and fast and precise responses. In addition, a deeper analysis of the level of research success needs to be synchronized with the cost-benefit analysis and performance of the pipeline facilities so that all risks and hazards that have been conveyed can be minimized.

Installation of monitoring and detection systems to monitor pipe flow, temperature, and pressure in real-time so that anomalous events can be analyzed immediately. Conduct internal pipe cleaning and periodic inspections with intelligent pigs and drone technology for pipe damage detection. Kim et al., 2024 developed a real-time deep learning-based pipe monitoring method that can save the cost of pipe flow simulator licenses [

61]. Conducting regular and scheduled maintenance and repairs by providing a dedicated emergency response team, as well as complete materials and equipment for immediate response, where this emergency response event has been regulated in a special procedure that has an organizational structure and a team that has been trained and tested to deal with leakage events.

Provide specialized equipment to locate spills, such as booms and oil spill absorbent materials, to reduce the spread of oil spills that cause environmental pollution. Conduct audits and risk management periodically to assess and identify potential hazards, equipped with the history and results of inspections and repairs that have been carried out, so that the possibility of the occurrence of this leakage event can be measured and estimated.

Obtaining the right method to determine the exact location of the blockage in the pipeline, including the number of blockages, length, and thickness of the blockages that occur, so that proper handling of blockage events can be carried out immediately. This method of determining the location of the blockage must be established in a procedure so that it can be used as a guide to prevent repeated events from becoming a hazard in the future. Compliance with a country’s regulatory rules and following international standards (API) is something that must be done as an emergency preparedness step, and things that may conflict with local and international laws so as not to increase company losses that cause the termination of the oil and gas industry management license contract.