Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

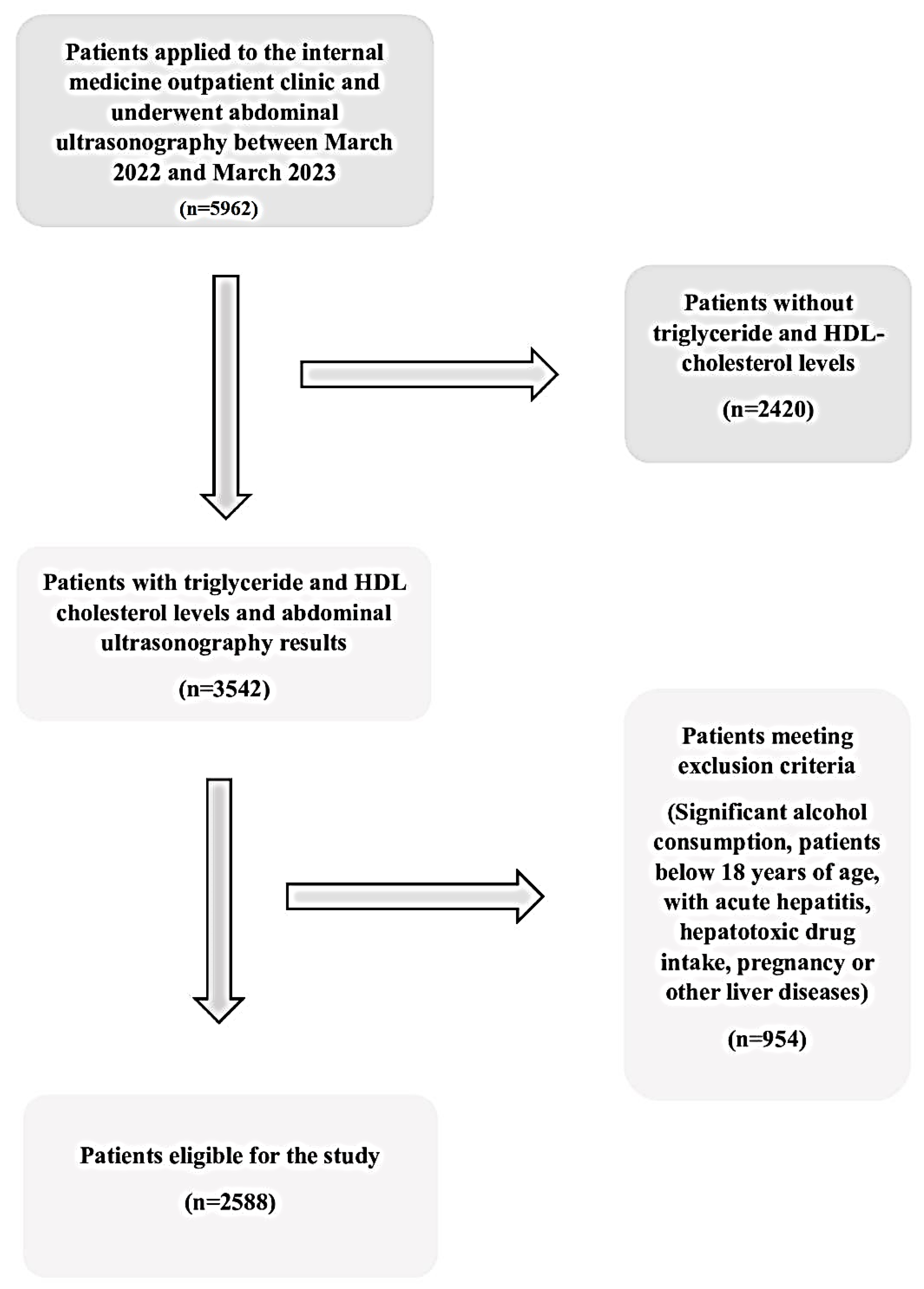

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Laboratory and Radiological Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis:

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| NASH | Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| US | Ultrasound |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| APRI | AST to platelet ratio index |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 |

| EASL | European Association for the Study of the Liver |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| WBC | White blood cell |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| PLT | Platelet |

References

- Pouwels S, Sakran N, Graham Y, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022 Mar 14;22(1):63. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang F, Han Y, Zheng L, et al. Association between chitinase-3-like protein 1 and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ir J Med Sci. 2024 Aug;193(4):1843-1853. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, AJ. The clinical features, diagnosis and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2004 Aug; 8(3): 521-33, viii. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reccia I, Kumar J, Akladios C, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A sign of systemic disease. Metabolism. 2017 Jul;72:94-108. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi R, Iuculano F, Pallini G, et al. Nutrients, Genetic Factors, and Their Interaction in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Nov 19;21(22):8761. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55(6):2005-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenzer NF, Springer F, Schraml C, et al. Non-invasive assessment and quantification of liver steatosis by ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance. J Hepatol. 2009;51(3):433-45. Epub 20090611. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernaez R, Lazo M, Bonekamp S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011 Sep 2;54(3):1082-1090. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou Y, Zhong L, Hu C, et al. Association between the alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase ratio and new-onset non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a nonobese Chinese population: a population-based longitudinal study. Lipids Health Dis. 2020 Nov 25;19(1):245. [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti AE, Bondesan A, Rondinelli E, et al. The Role of Aspartate Transaminase to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) for the Prediction of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in Severely Obese Children and Adolescents. Metabolites. 2022 Feb 8;12(2):155. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell EE, Wong VW, Rinella M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet. 2021 Jun 5;397(10290):2212-2224. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, ZM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease–a global public health perspective. Journal of hepatology. 2019;70(3):531-44.

- Tabacu L, Swami S, Ledbetter M, et al. Socioeconomic status and health disparities drive differences in accelerometer-derived physical activity in fatty liver disease and significant fibrosis. PLoS One. 2024 ;19(5):e0301774. 9 May. [CrossRef]

- Summart U, Thinkhamrop B, Chamadol N, et al. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the Northeast of Thailand: A population-based cross-sectional study. F1000Res. 2017;6:1630. Epub 20170904. [CrossRef]

- Eguchi Y, Hyogo H, Ono M, et al. Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population from 2009 to 2010 in Japan: a multicenter large retrospective study. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(5):586-95. Epub 20120211. [CrossRef]

- Kim KS, Hong S, Han K, et al. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with cardiovascular disease and all cause death in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: nationwide population based study. BMJ. 2024 Feb 13;384:e076388. [CrossRef]

- Ballestri S, Zona S, Targher G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with an almost twofold increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):936-44. [CrossRef]

- Amernia B, Moosavy SH, Banookh F, et al. FIB-4, APRI, and AST/ALT ratio compared to FibroScan for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Bandar Abbas, Iran. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):453. [CrossRef]

- Leoni S, Tovoli F, Napoli L, et al. Current guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review with comparative analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(30):3361-73. [CrossRef]

- Long MT, Pedley A, Colantonio LD, et al. Development and Validation of the Framingham Steatosis Index to Identify Persons With Hepatic Steatosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Aug;14(8):1172-1180.e2. [CrossRef]

- Lin MS, Lin HS, Chang ML, et al. Alanine aminotransferase to aspartate aminotransferase ratio and hepatitis B virus on metabolic syndrome: a community-based study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jul 29;13:922312. [CrossRef]

- Thong VD, Quynh BTH. Correlation of Serum Transaminase Levels with Liver Fibrosis Assessed by Transient Elastography in Vietnamese Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:1349-55. [CrossRef]

- Jamialahmadi T, Bo S, Abbasifard M, et al. Association of C-reactive protein with histological, elastographic, and sonographic indices of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in individuals with severe obesity. J Health Popul Nutr. 2023 Apr 7;42(1):30. [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra M, Van Eck M. High-density lipoproteins and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Atheroscler Plus. 2023 Aug 19;53:33-41. [CrossRef]

- Tomizawa M, Kawanabe Y, Shinozaki F, et al. Triglyceride is strongly associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among markers of hyperlipidemia and diabetes. Biomed Rep. 2014 Sep;2(5):633-636. [CrossRef]

- Kawano Y, Cohen DE. Mechanisms of hepatic triglyceride accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(4):434-41. Epub 20130209. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Zhan F, Peng T, et al. Association between the Triglyceride-Glucose Index and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Eur J Med Res. 2023 Sep 19;28(1):355. [CrossRef]

- Wu KT, Kuo PL, Su SB, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease severity is associated with the ratios of total cholesterol and triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(2):420-5.e1. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda Y, Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, et al. Triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio is an independent predictor of incident fatty liver; a population-based cohort study. Liver Int. 2016;36(5):713-20. Epub 20151105. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Qin H, Qiu S, et al. Correlation of triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among the non-obese Chinese population with normal blood lipid levels: a retrospective cohort research. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):162. [CrossRef]

- Zhou YG, Tian N, Xie WN. Total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein ratio and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a population with chronic hepatitis B. World J Hepatol. 2022 Apr 27;14(4):791-801. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S. Incidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetic patients. Yeditepe Medical Journal 2016;12(37-38): 960-967. [CrossRef]

- Sefa Sayar M, Bulut D, Acar A. Evaluation of hepatosteatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2023 Feb;24(1):11-15. [CrossRef]

- Yin JY, Yang TY, Yang BQ, et al. FibroScan-aspartate transaminase: A superior non-invasive model for diagnosing high-risk metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024 ;30(18):2440-2453. 14 May. [CrossRef]

- Rigor J, Diegues A, Presa J, et al. Noninvasive fibrosis tools in NAFLD: validation of APRI, BARD, FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score, and Hepamet fibrosis score in a Portuguese population. Postgrad Med. 2022 May;134(4):435-440. [CrossRef]

- Nanji AA, French SW, Freeman JB. Serum alanine aminotransferase to aspartate aminotransferase ratio and degree of fatty liver in morbidly obese patients. Enzyme. 1986;36(4):266-9. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics and Findings |

Entire patients (n:2588) |

|---|---|

| Gender (F/M) | 1631/957 |

| Age (years) | 45.31±12.50 |

| WBC (109/L) | 7.35±1.93 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 4.32±1.50 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 13.58±1.78 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 258.81±70.92 |

| Glucose (>mg/dl) | 109.34±41.40 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.25±1.48 |

| AST (U/L) | 24.80±38.88 |

| ALT (U/L) | 29.91±49.99 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 84.37±36.09 |

| LDH (U/L) | 182.75±47.96 |

| Creatinine (>mg/dl) | 0.75±0.16 |

| Triglyceride (>mg/dl) | 147.42±93.89 |

| HDL cholesterol (>mg/dl) | 49.28±12.82 |

| Total cholesterol (>mg/dl) | 189.23±41.0 |

| Uric acid (>mg/dl) | 4.70±1.31 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 45.63±3.0 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 4.91±9.32 |

| Characteristics and Findings |

Patients without NAFLD (n:1270) |

Patients with NAFLD (n:1318) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.42±13.33 | 49.07±10.34 | <0.001 |

| Gender (F/M) | 811/459 | 820/498 | 0,249 |

| WBC (109/L) | 7.11±1,91 | 7,58±1.92 | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 4.23±1.56 | 4.40±1.45 | 0.005 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 13,4±1,85 | 13,76±1,70 | <0.001 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 257.26±76.02 | 260.31±65.62 | 0.275 |

| Glucose (>mg/dl) | 100.63±31.48 | 117.73±47.61 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.88±1.30 | 6.52±1.54 | <0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 22.67±30.62 | 26.84±45.33 | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 24.02±36.87 | 35.60±59.45 | <0.001 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 82.38±42.0 | 86.45±28.49 | 0.013 |

| LDH (U/L) | 178.05±46.45 | 187.77±49.06 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (>mg/dl) | 0.74±0.15 | 0.76±0.16 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride (>mg/dl) | 122.67±80.57 | 171.27±99.50 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (>mg/dl) | 51.26±13.54 | 47.37±11.78 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (>mg/dl) | 181.16±40.62 | 197.02±39.88 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (>mg/dl) | 4.34±1.22 | 5.06±1,30 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 45.41±3.28 | 45.83±2.70 | 0.002 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 4.31±9.85 | 5,49±8.75 | 0.007 |

| Patients without NAFLD (n:1270) |

Patients with NAFLD (n:1318) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

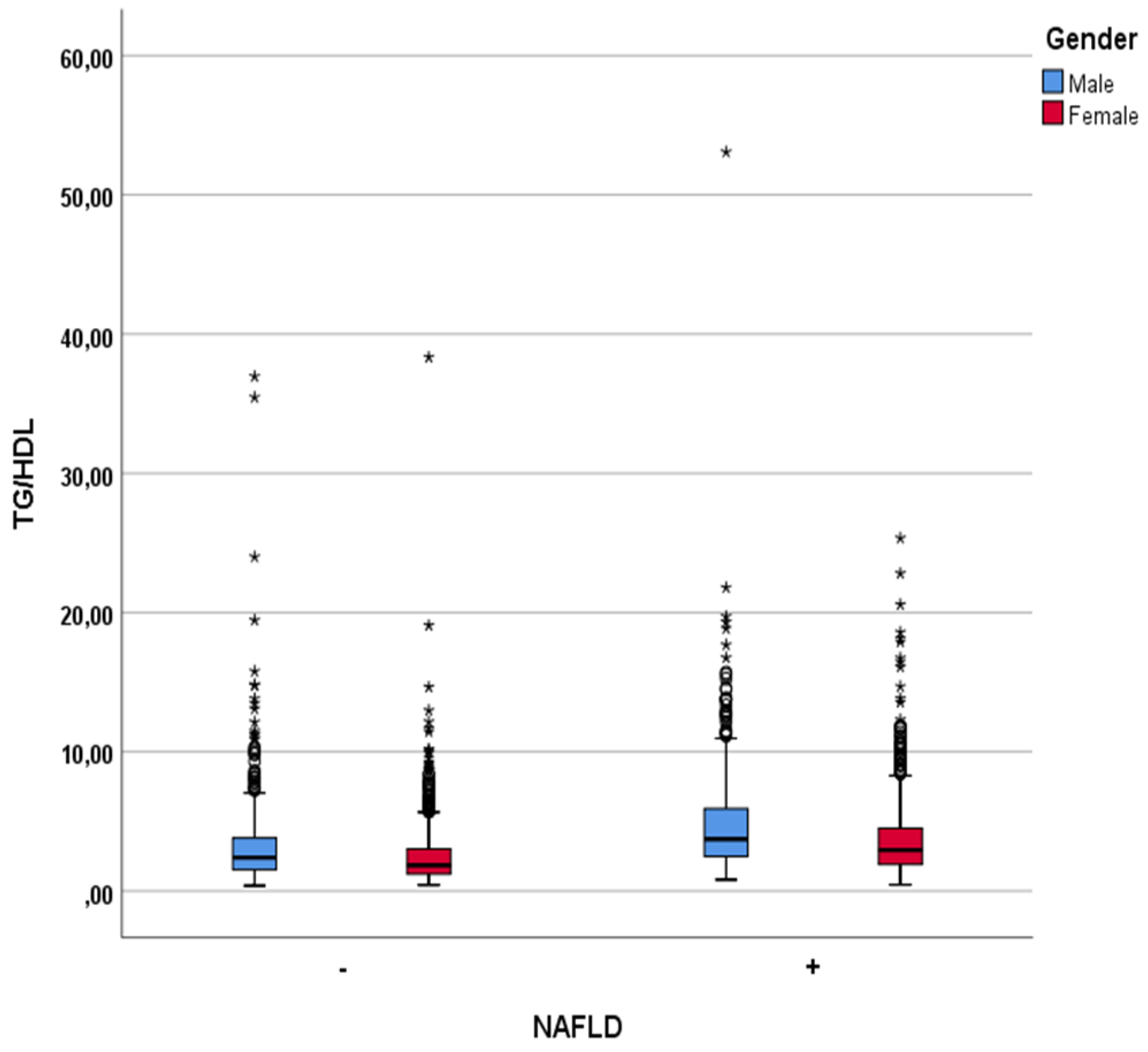

| TG/HDL ratio | 2.79±2.83 | 4.08±3.30 | <0.001 |

| TC/HDL ratio | 3.75±1.39 | 4.36±1.24 | <0.001 |

| ALT/AST ratio | 0.99±0.39 | 1.23±0.49 | <0.001 |

| APRI | 0.32±0.64 | 0.35±0.62 | <0.001 |

| FIB-4 score | 0.85±0.80 | 0.93±0.50 | <0.001 |

| TG/Glucose ratio | 1.24±0.74 | 1.54±0.88 | <0.001 |

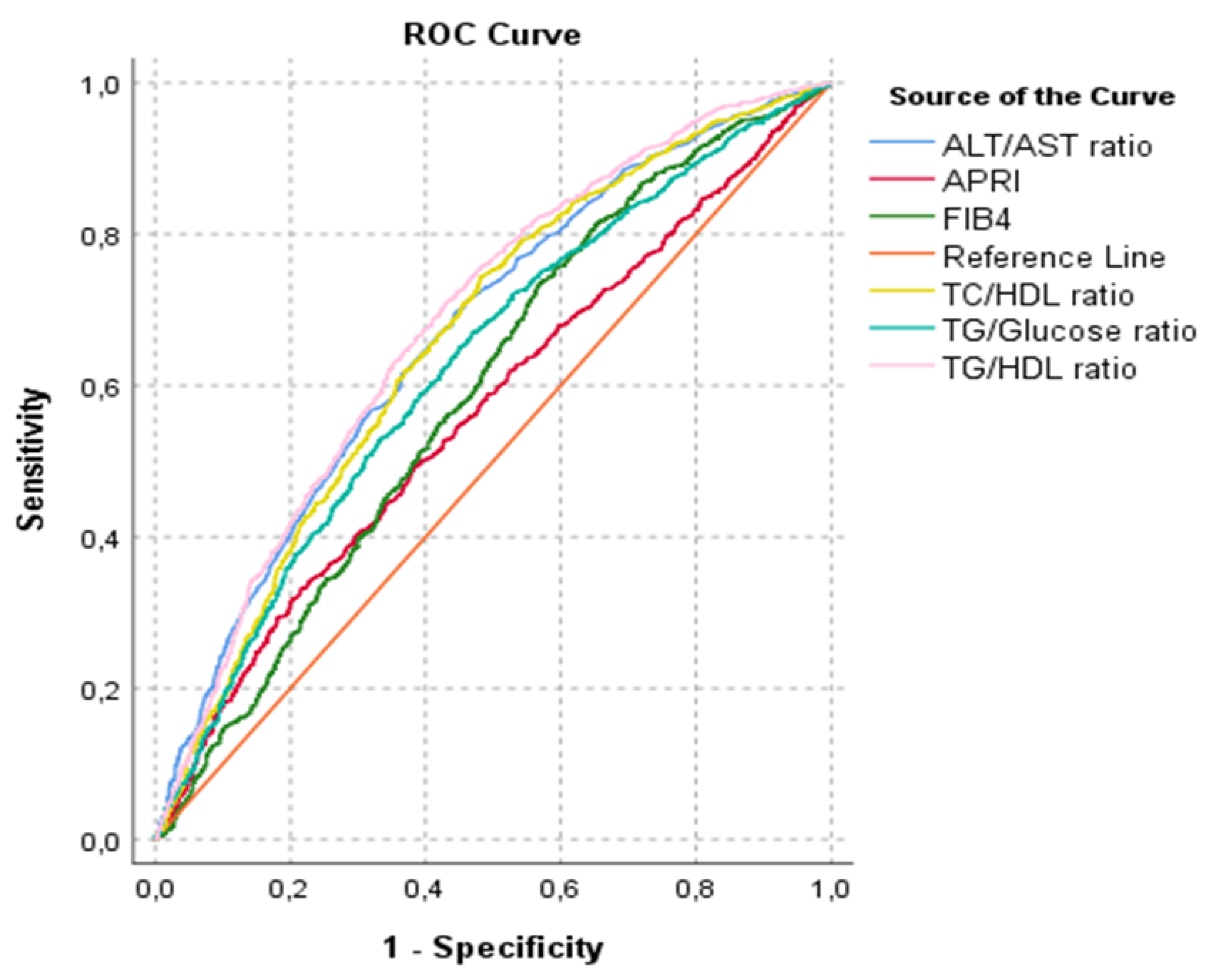

| AUROC for NAFLD (%95 CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Tg/HDL ratio | 0.682 (0.662-0.703) | <0.001 |

| TC/HDL ratio | 0.661 (0.640-0.682) | <0.001 |

| ALT/AST ratio | 0.668 (0.647-0.689) | <0.001 |

| APRI | 0.565 (0.543-0.587) | <0.001 |

| FIB-4 | 0.591 (0.569-0.613) | <0.001 |

| Tg/Glucose ratio | 0.626 (0.604-0.647) | <0.001 |

| TG/HDL Ratio | N of Patients Without NAFLD | N of Patients with NAFLD |

Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1.86 | 578 | 254 | 832 |

<0.001 |

| ≥1.86 | 692 | 1064 | 1756 | |

| Total | 1270 | 1318 | 2588 |

| Parameter | r (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.139 (0.066-0.210) | <0.001 |

| WBC | 0.183 (0.114-0.246) | <0.001 |

| Hgb | 0.213 (0.140-0.287) | <0.001 |

| PLT | -0.008 (-0.083-0.062) | 0.818 |

| Creatinine | 0.174 (0.102-0.237) | <0.001 |

| AST | 0.146 (0.077-0.212) | <0.001 |

| ALT | 0.229 (0.158-0.296) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid | 0.272 (0.208-0.337) | <0.001 |

| Glucose | 0.244 (0.179-0.309) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c | 0.242 (0.168-0.311) | <0.001 |

| LDH | 0.021 (-0.044-0.090) | 0.554 |

| APRI | 0.109 (0.038-0.178) | 0.002 |

| FIB-4 | 0.061 (-0.010-0.134) | 0.084 |

| ALT/AST ratio | 0.249 (0.183-0.315) | <0.001 |

| TG/Glucose ratio | 0.795 (0.763-0.825) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).