1. Introduction

Viral respiratory diseases in poultry have been implicated in significant mortalities and economic losses in the poultry industry worldwide for decades [

1]. The financial losses are associated with concurrent or secondary infections, which result in significant clinical disease and lesions [

2]. However, experimental infection to study viral pathogenesis and vaccine safety/efficacy may not produce the significant lesions seen in the field situation [

3,

4,

5]. This challenge creates a need for an objective grading scheme to score subtle histological changes that may go unnoticed in controlled experimental trials. The histologic respiratory index (HRI) is designed to assess multiple histologic features that are expected to change after experimental viral infection in poultry.

The histopathological changes in the affected tissues provide significant information about the pathogenicity, virulence, tissue tropism, and comparative pathogenicity of various pathogens. This helps understand the dynamics, clinical severity, and mechanism of infection progression [

6]. The histological lesions assessment can also serve as a subjective tool, a scoring system, to evaluate the efficacy of vaccines and the development of an integrated challenge model for vaccine assessment [

7]. Our team has previously developed a specific scoring system for the hock joints and gastrocnemius tendons, known as histologic inflammation scores, to evaluate the extent of turkey reovirus infection [

8]. This scoring system represents a unique and objective tool, not only in the field of turkey reovirus diagnosis but also in research studies. This histologic inflammation score was effectively utilized to understand the pathogenicity of turkey reoviruses, as well as any newly emerged variants and their host ranges [

9,

10]. It also helped determine the dynamics of infection and associated immunity [

11]. Moreover, it was a crucial tool in the challenge model, which was used to assess the developed vaccines against turkey reoviruses [

12]

Therefore, this work explains the detailed HRI and the validation in birds inoculated experimentally with two poultry respiratory viruses. The validated HRI will be used in experimental pathogenicity and vaccine evaluation trials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Grading Scheme:

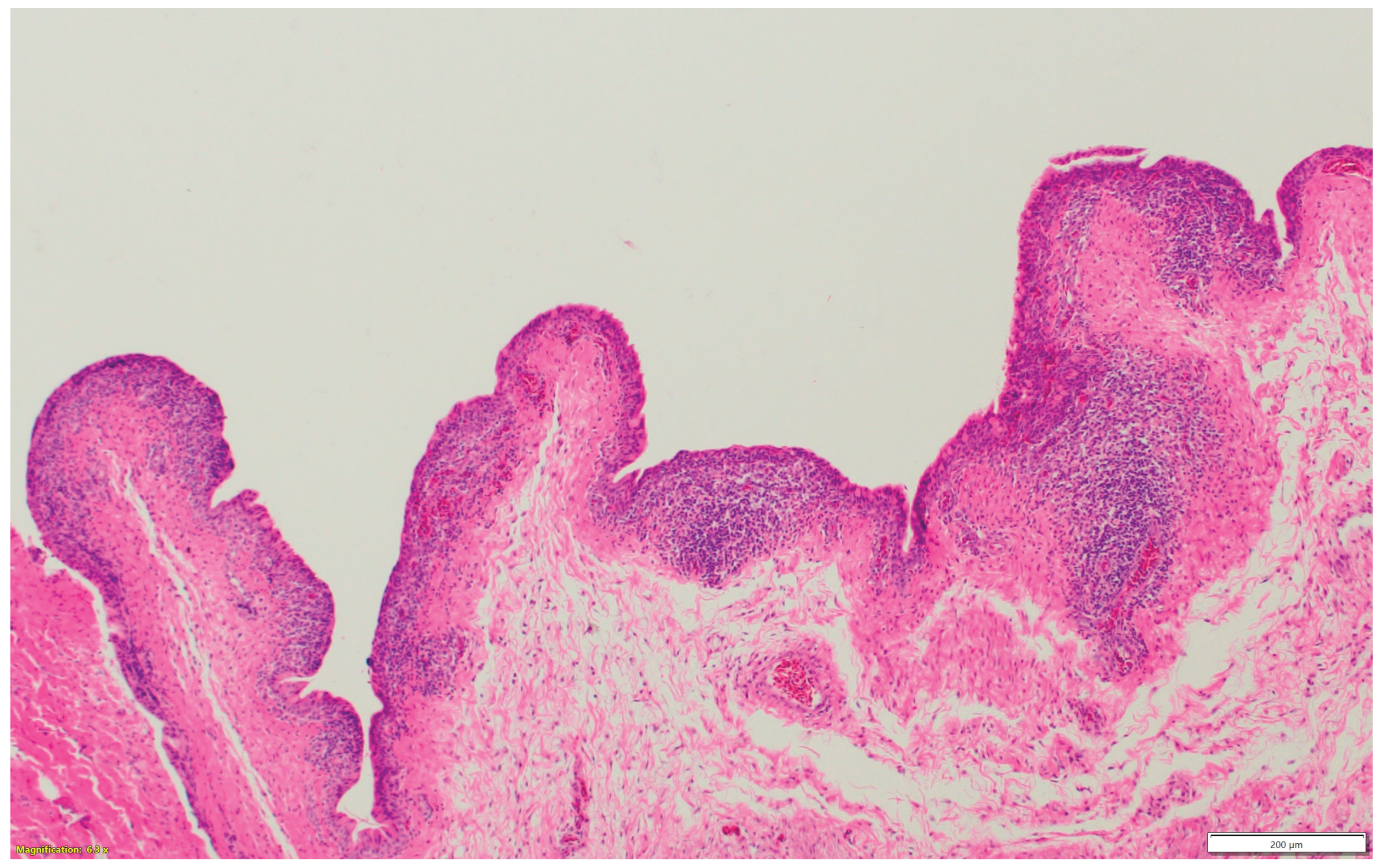

Nasal sinuses (

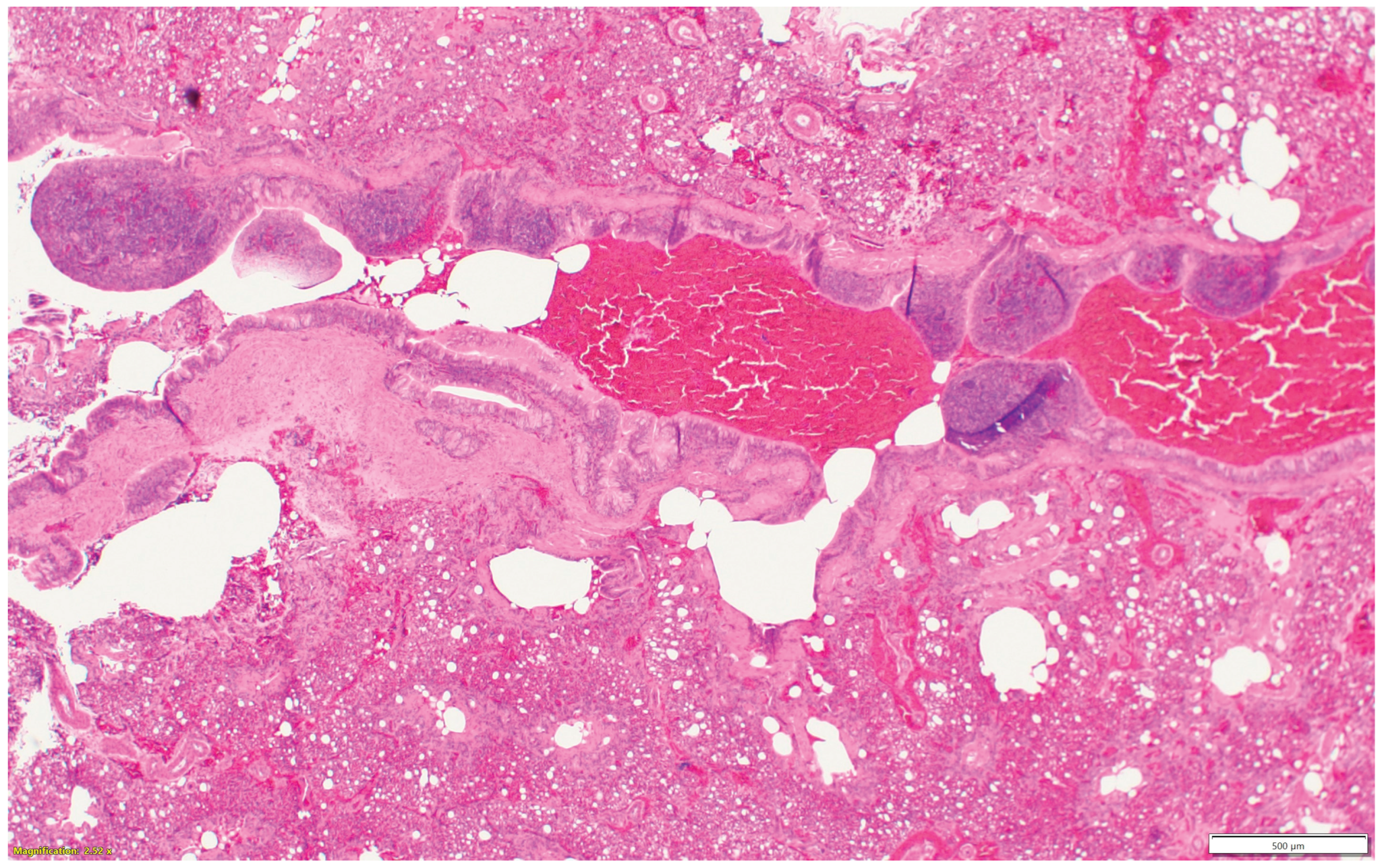

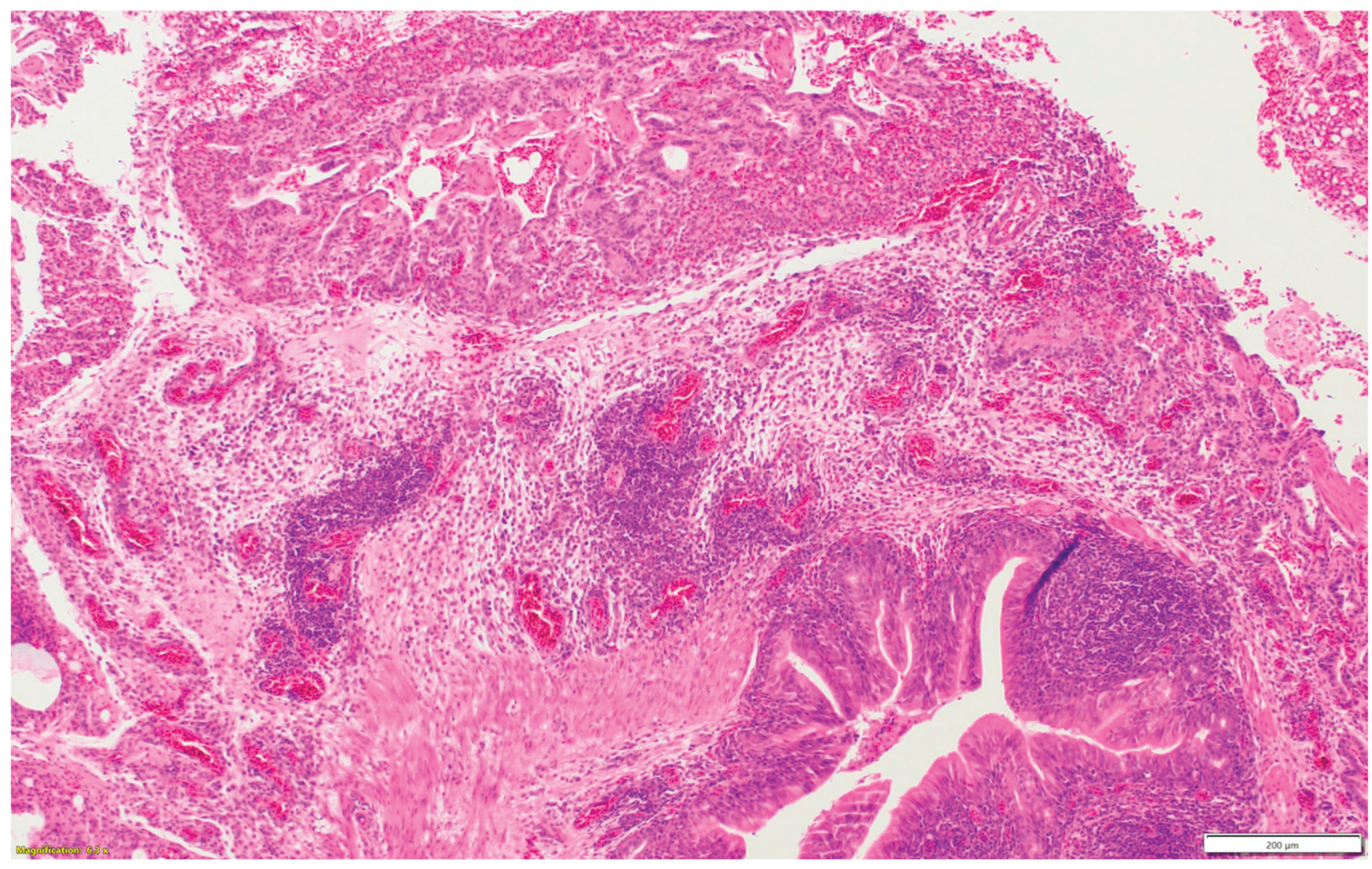

Figure 1a-d), including the nasal turbinate and infraorbital sinus, are scored at two levels: mucosa and submucosa. Respiratory mucosa hyperplasia/metaplasia takes 1-point, desquamated mucosa within the lumen takes one more point. Submucosal lymphocytes take 1 point with a small number of lymphocytes and 2 points if they are too numerous to count (above 100 in one 400X microscopic field). An additional 1-point is added when there is infiltration of heterophils in the submucosa or mucosa. If there is vasculitis in the submucosa, 1-point is counted. The scores of the nasal turbinate and infraorbital sinuses are added to give total nasal sinus scores. Similarly, trachea and eyelids (

Figure 1e) are graded considering mucosal hyperplasia/metaplasia, luminal debris, submucosal lymphocytes, heterophils, and vasculitis (One point each). Lungs (

Figure 1f-h) are scored considering hyperplasia in the bronchial associated lymphoid tissue (BALT- 1point), germinal center formation (1 point), air capillaries lymphocytic infiltration (1 point or 2 points in more than 100 in one 400X microscopic field), and vasculitis (1 point) (Figure1a-h). The sum of scores of the nasal sinuses, trachea, lungs, and eyelids forms the value of the histologic respiratory index (HRI).

Figure 1a.

Normal nasal and infraorbital sinuses.

Figure 1a.

Normal nasal and infraorbital sinuses.

Figure 1b.

Lymphocytic infiltration in the submucosa of the nasal sinus.

Figure 1b.

Lymphocytic infiltration in the submucosa of the nasal sinus.

Figure 1c.

Nasal respiratory mucosa hyperplasia and metaplasia, along with lymphocytic infiltration in the submucosa of the nasal sinus.

Figure 1c.

Nasal respiratory mucosa hyperplasia and metaplasia, along with lymphocytic infiltration in the submucosa of the nasal sinus.

Figure 1d.

Heterophilic infiltration in the mucosa and submucosa of the infraorbital sinus, mixed with lymphocytic infiltration as well as vasculitis.

Figure 1d.

Heterophilic infiltration in the mucosa and submucosa of the infraorbital sinus, mixed with lymphocytic infiltration as well as vasculitis.

Figure 1e.

Multifocal lymphocytic infiltration and vasculitis in the submucosa of the eyelid.

Figure 1e.

Multifocal lymphocytic infiltration and vasculitis in the submucosa of the eyelid.

Figure 1f.

Bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) hyperplasia around the secondary bronchi (Lungs).

Figure 1f.

Bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) hyperplasia around the secondary bronchi (Lungs).

Figure 1g.

Multifocal vasculitis around the secondary bronchi (Lungs).

Figure 1g.

Multifocal vasculitis around the secondary bronchi (Lungs).

Figure 1h.

Multifocal lymphocytic infiltration in the air capillaries around the parabronchus (Lungs).

Figure 1h.

Multifocal lymphocytic infiltration in the air capillaries around the parabronchus (Lungs).

2.2. Validation of HRI:

Nasal sinuses, trachea, lungs, and eyelids from experimentally infected birds were scored in comparison to non-infected controls. Four trials were conducted where turkeys and chickens were inoculated with avian metapneumovirus (aMPV subgroup B- two trials in turkeys and one trial in chickens) and low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI H4N6- one trial in turkeys). Turkeys and chickens were inoculated in two trials with aMPV subgroup B via oral/nasal route at different ages (1-, 7-, and 14-day-old turkeys, 7- and 14-day-old chickens) and were euthanized followed by sample collection at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post inoculation (DPI) for histological evaluation. In another trial, turkeys were inoculated with aMPV subgroup B at 7 days of age via the oral/nasal route, and euthanasia with sample collection was done 10 DPI. Using another respiratory virus, turkeys were inoculated with LPAI H4N6 via oral/nasal route at 7 days old, and birds were euthanized and samples collected for histologic evaluation at 7 DPI.

3. Results

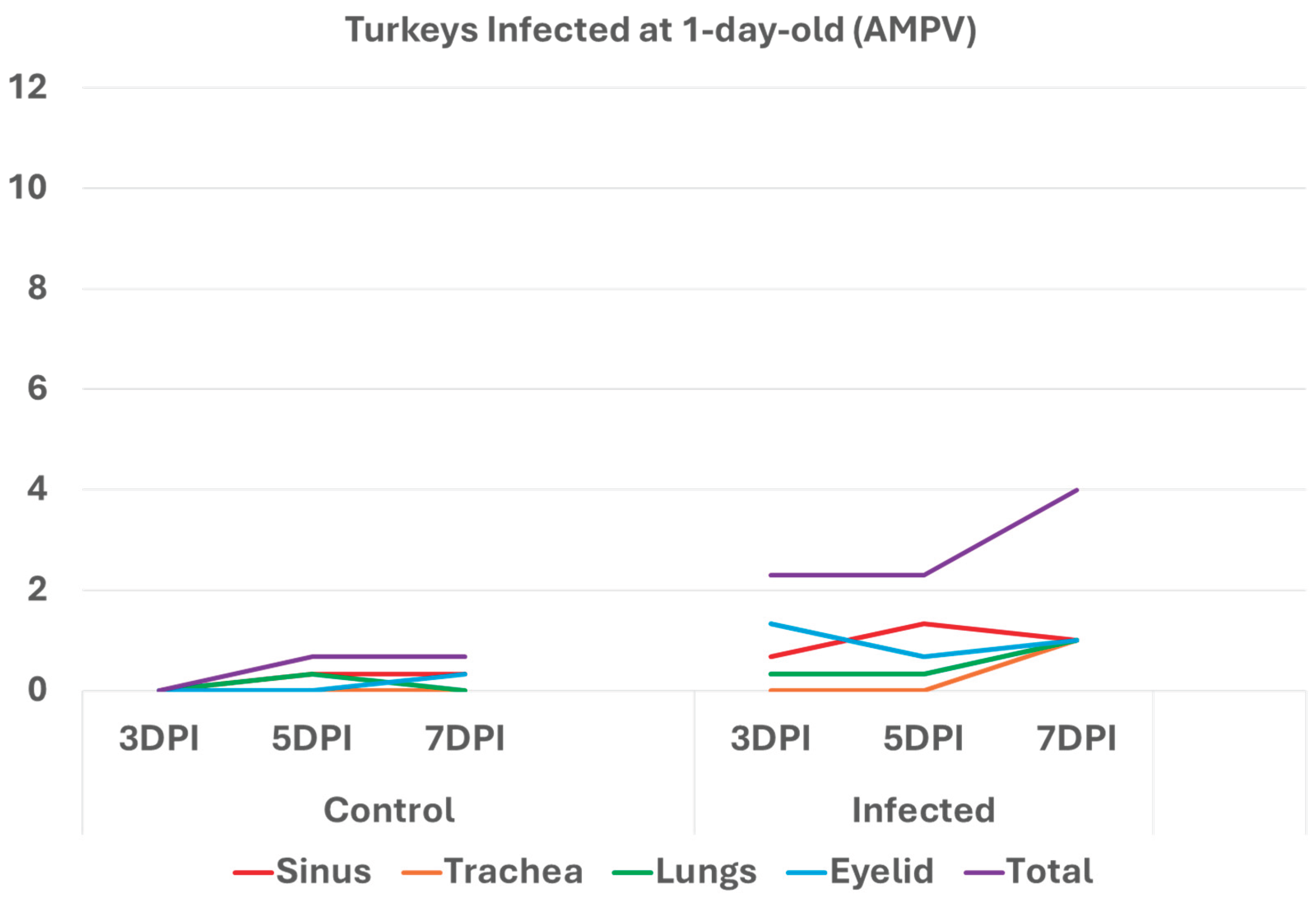

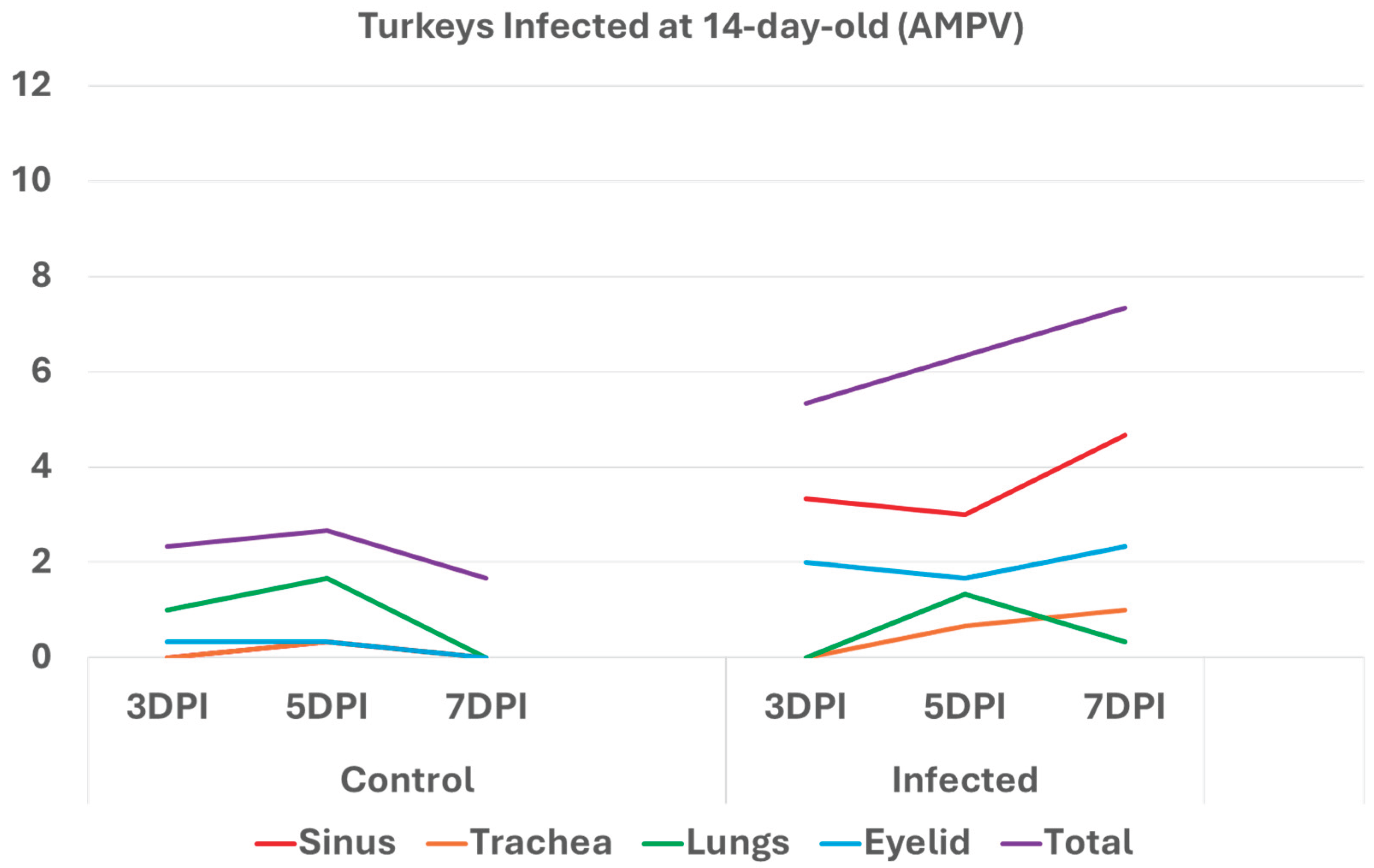

3.1. Turkeys infected with aMPV at 1-day-old (Figure 2a) had a higher total HRI compared with noninfected controls. The gap between the two groups increased significantly as the birds aged. Sinus and eyelid scores were the main contributors to the difference between the control and infected groups. A similar pattern was observed in groups inoculated at 7- and 14-day-old (Figure 2 b-c), but with higher scores. Sinus was the central part of the score difference, followed by the eyelids.

Figure 2a.

Figure 2a. Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 1-day-old. Total HRI, sinus, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 2a.

Figure 2a. Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 1-day-old. Total HRI, sinus, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 2b.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 7-day-old. Total HRI, sinus, and trachea scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 2b.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 7-day-old. Total HRI, sinus, and trachea scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 2c.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 14 days of age. Total HRI, sinus, eyelid, and trachea scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 2c.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 14 days of age. Total HRI, sinus, eyelid, and trachea scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

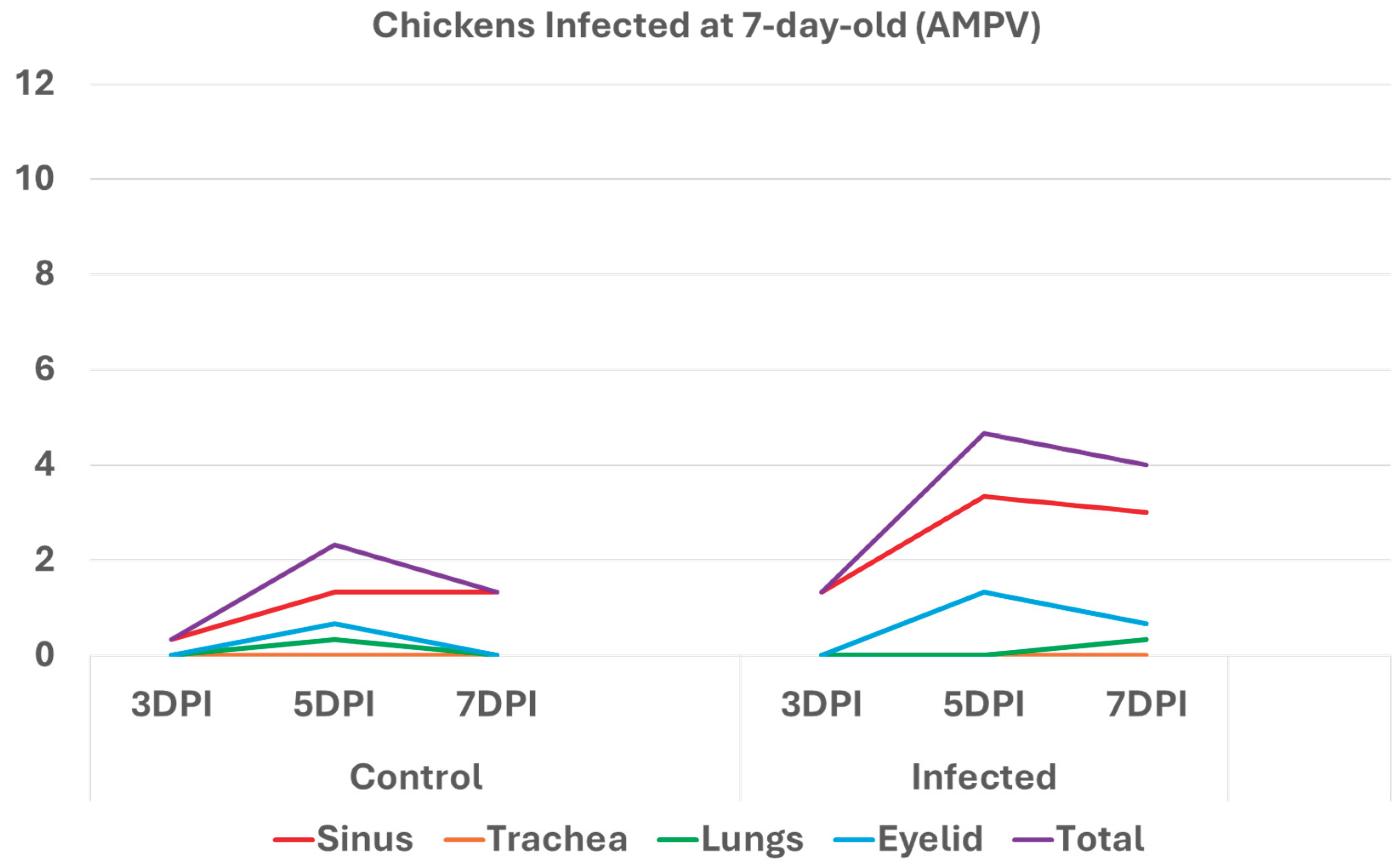

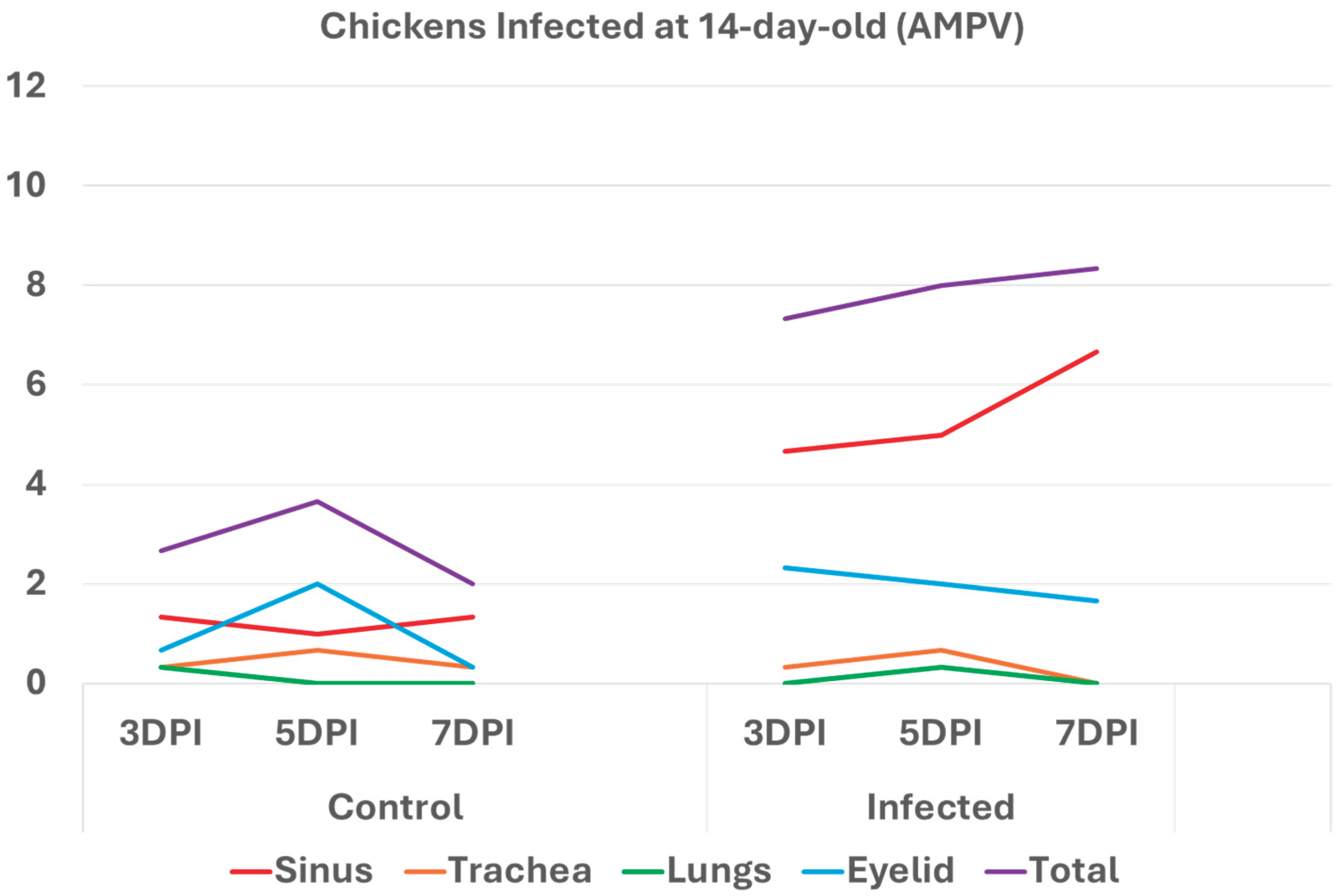

3.2. Chickens infected with aMPV at 7- and 14-day-old (Figure 3a-b): A similar pattern to the turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 7- and 14-day-old. Similarly, sinuses and eyelids created the main difference between the control and infected groups.

Figure 3a.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in chickens inoculated with AMPV at 7-day-old. Total HRI, sinus, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 3a.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in chickens inoculated with AMPV at 7-day-old. Total HRI, sinus, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 3b.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in chickens inoculated with AMPV at 14 days of age. Total HRI, sinus, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls. .

Figure 3b.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 3-, 5-, and 7-days post infection (DPI) in chickens inoculated with AMPV at 14 days of age. Total HRI, sinus, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls. .

3.3. Turkeys inoculated with aMPV at 7 days of age showed higher lesion scores at 10 DPI compared with the non-infected control group. Sinus and eyelids were the main organs scoring points compared with other organs (Figure 4a).

Figure 4a.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 10 days post-infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 7 days of age. Total HRI, sinus, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 4a.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 10 days post-infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with AMPV at 7 days of age. Total HRI, sinus, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

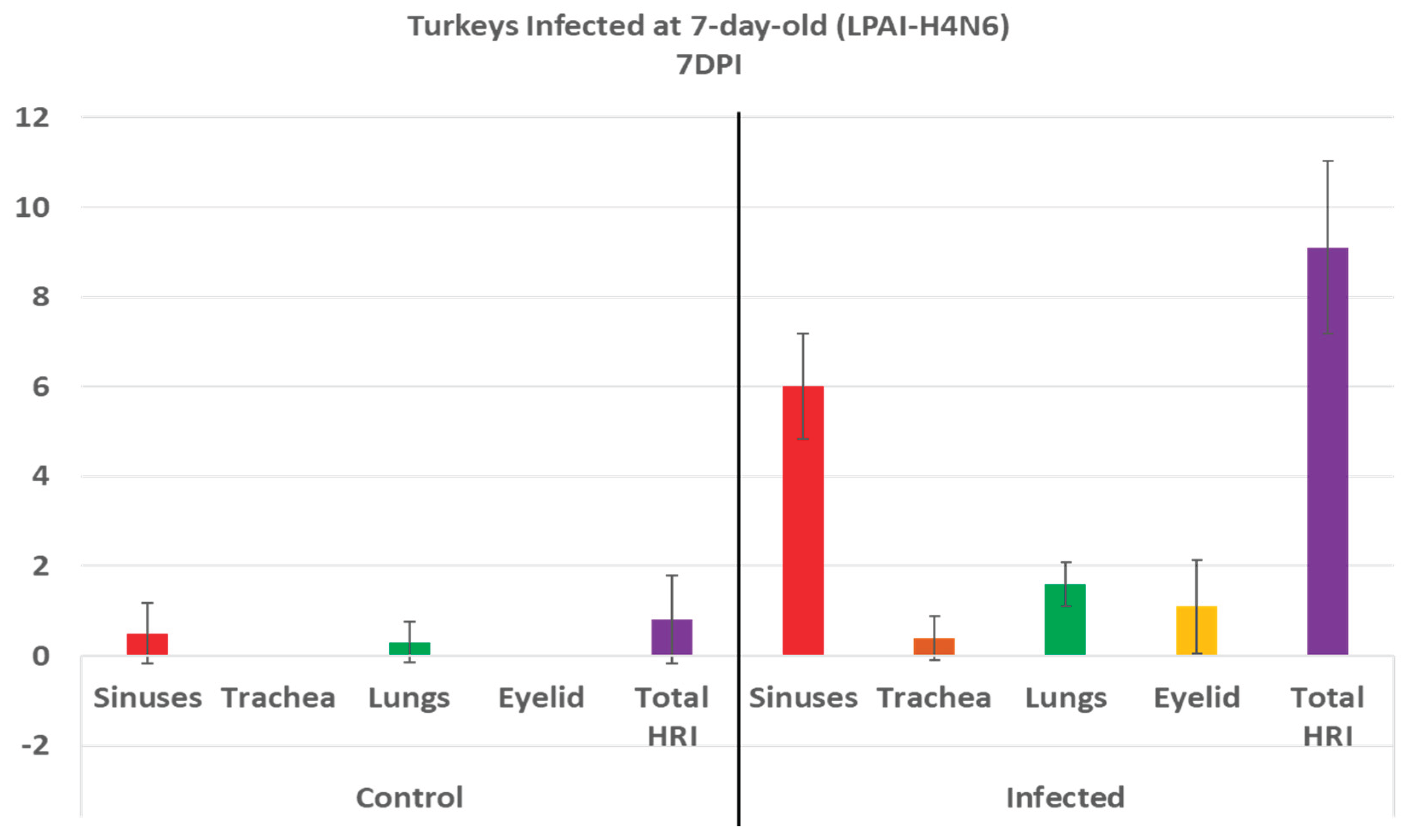

3.4. Turkeys inoculated with low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI-H4N6) at 7 days of age had also increased histologic lesion scores at 7 DPI compared with the non-infected control group. Sinus, lungs, eyelids, and trachea were orderly contributing to a higher total HRI (Figure 4b).

Figure 4b.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 7 days post infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI-H4N6) at 7 days of age. Total HRI, sinus, trachea, lungs, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

Figure 4b.

Histologic respiratory index (HRI) at 7 days post infection (DPI) in turkeys inoculated with low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI-H4N6) at 7 days of age. Total HRI, sinus, trachea, lungs, and eyelid scores are higher in infected birds compared with noninfected controls.

4. Discussion

The development of an objective histologic score for respiratory organs in poultry is necessary for a detailed and unbiased evaluation of disease pathogenicity. It is also a potential tool in establishing the challenge model needed for any vaccine evaluation. While conducting viral respiratory pathogenicity trials under a controlled environment, observing striking gross lesions may not be achieved due to the absence of secondary bacterial infection in the experimentally infected birds [

13]. Additionally, experimentally infected birds may recover after a few days with no observable lesions or clinical signs of disease [

14]. That is why using a validated histologic score for respiratory organs is strongly recommended to accurately monitor microscopic changes in a metric pattern. The HRI not only provides a sum of scores for different respiratory organs, considering expected cellular changes after respiratory viral pathogens in poultry, but it also offers detailed information about lesion intensity, progression, and distribution in various respiratory organs.

The score takes into account a variety of mucosal and submucosal changes that occur during and after respiratory viral infections. Respiratory mucosal cells hyperplasia, metaplasia, breakdown, and subsequent formation of luminal debris are subsequent changes seen during respiratory viral infection in poultry [

15,

16,

17]. Scoring any respiratory mucosal cellular change is representative, as well as the additional score for the luminal cellular debris after respiratory mucosal cell breakdown. It reflects the intensity of the infection as well as the pathogenicity/virulence[

18,

19]. Additionally, submucosal lymphocytic inflammation (1 point or 2 points due to excessive lymphocytes) as well as an additional point for mucosal/submucosal heterophilic infiltration is a correct referral to the intensity of the host response, which is proportional to virulence or involvement in a mild secondary infection [

20,

21]. Adding a point for vasculitis is a fair representation of respiratory viral pathogenesis [

22].

Respiratory viral pathogenicity is to be assessed via different features compared within the respiratory organs. In lungs, BALT hyperplasia reflects an immune response to infection or vaccination [

23]. An additional point regarding germinal center formation explains both the intensity and duration of the immune response. Furthermore, lymphocytic infiltration within air capillaries and/or vasculitis in avian lungs are observed features with respiratory viral infections in poultry [

24].

Analyzing the scores of different organs involved in the HRI enables an understanding of the significant parts of the HRI. This can help with the slight modification of the grading scheme to obtain the best scoring criteria for different respiratory diseases. In AMPV, relying mainly on the sinuses and eyelids, and less likely on the trachea and lungs, can support an accurate grading for evaluation of pathogenicity. Similarly, in LPAI H4N6, relying mainly on sinuses and eyelids is helpful, but with the addition of lungs to the list, in which scores are significantly higher in infected birds compared with non-infected controls at 7DPI (

Figure 4b).

The nearly similar pattern in inoculated chickens and turkeys with AMPV (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) and in turkeys inoculated with AMPV and LPAI H4N6 confirms the reliability of the developed HRI. Further validation and refinement are ongoing with additional experimental trials using different respiratory pathogens, at various ages and routes of inoculation, and at other times post-inoculation.

5. Conclusions

The developed and validated HRI can be reliably used in grading lesions in experimentally infected birds. Validation with AMPV and LPAI was established. Further validation and minor modifications will be needed for other poultry respiratory. The developed HRI will be recruited in the challenge models for vaccine trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S., S.M; Methodology, T.S., M.S., and N.B.; Optimization, T.S.; Writing original draft, T.S.; Writing-reviewing and editing, T.S., M.S., N.B., S.M.; Project administration, T.S., S.M.; Funding acquisition, T.S., S.M.

Funding

South Dakota Board of Regent and US Poultry and Egg

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) 2408-073A 2025-06-01.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, H.; Pan, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, W.; Wei, X.; He, Y.; Xu, T.; Shi, K.; Si, H. Review of Respiratory Syndromes in Poultry: Pathogens, Prevention, and Control Measures. Veterinary Research 2025 56:1 2025, 56, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Samy, A.; Naguib, M.M. Avian Respiratory Coinfection and Impact on Avian Influenza Pathogenicity in Domestic Poultry: Field and Experimental Findings. Veterinary Sciences 2018, Vol. 5, Page 23 2018, 5, 23. [CrossRef]

- Kariithi, H.M.; Welch, C.N.; Ferreira, H.L.; Pusch, E.A.; Ateya, L.O.; Binepal, Y.S.; Apopo, A.A.; Dulu, T.D.; Afonso, C.L.; Suarez, D.L. Genetic Characterization and Pathogenesis of the First H9N2 Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses Isolated from Chickens in Kenyan Live Bird Markets. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 78. [CrossRef]

- Kye, S.J.; Park, M.J.; Kim, N.Y.; Lee, Y.N.; Heo, G.B.; Baek, Y.K.; Shin, J.I.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, Y.J. Pathogenicity of H9N2 Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses of Different Lineages Isolated from Live Bird Markets Tested in Three Animal Models: SPF Chickens, Korean Native Chickens, and Ducks. Poult Sci 2021, 100. [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.A.; Allée, C.; Courtillon, C.; Szerman, N.; Lemaitre, E.; Toquin, D.; Mangart, J.M.; Amelot, M.; Eterradossi, N. Host Specificity of Avian Metapneumoviruses. Avian Pathology 2019, 48, 311–318. [CrossRef]

-

Fenner’s Veterinary Virology, 78. [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Corley, K.N.; Olivier, A.K.; Meyerholz, D.K. Principles for Valid Histopathologic Scoring in Research. Vet Pathol 2013, 50, 10.1177/0300985813485099. [CrossRef]

- Sharafeldin, T.A.; Mor, S.K.; Bekele, A.Z.; Verma, H.; Goyal, S.M.; Porter, R.E. The Role of Avian Reoviruses in Turkey Tenosynovitis/Arthritis. Avian Pathology 2014, 43, 371–378. [CrossRef]

- Sharafeldin, T.A.; Mor, S.K.; Verma, H.; Bekele, A.Z.; Ismagilova, L.; Goyal, S.M.; Porter, R.E. Pathogenicity of Newly Emergent Turkey Arthritis Reoviruses in Chickens. Poult Sci 2015, 94, 2369–2374. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sharafeldin, T.A.; Sobhy, N.M.; Goyal, S.M.; Porter, R.E.; Mor, S.K. Comparative Pathogenesis of Turkey Reoviruses. Avian Pathology 2022, 51, 435–444. [CrossRef]

- Sharafeldin, T.A.; Mor, S.K.; Sobhy, N.M.; Xing, Z.; Reed, K.M.; Goyal, S.M.; Porter, R.E. A Newly Emergent Turkey Arthritis Reovirus Shows Dominant Enteric Tropism and Induces Significantly Elevated Innate Antiviral and T Helper-1 Cytokine Responses. PLoS One 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Porter, R.E.; Mor, S.K.; Goyal, S.M. Efficacy and Immunogenicity of Recombinant Pichinde Virus-Vectored Turkey Arthritis Reovirus Subunit Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 486. [CrossRef]

- Trottein, F.; Alcorn, J.F. Editorial: Secondary Respiratory Infections in the Context of Acute and Chronic Pulmonary Diseases. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2764. [CrossRef]

- Spickler, A.R.; Trampel, D.W.; Roth, J.A. The Onset of Virus Shedding and Clinical Signs in Chickens Infected with High-Pathogenicity and Low-Pathogenicity Avian Influenza Viruses. Avian Pathology 2008, 37, 555–577. [CrossRef]

- Histopathological Profiling of Respiratory Tract Lesions in Chickens Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281004753_Histopathological_Profiling_of_Respiratory_Tract_Lesions_in_Chickens (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Benyeda, Z.; Szeredi, L.; Mató, T.; Süveges, T.; Balka, G.; Abonyi-Tóth, Z.; Rusvai, M.; Palya, V. Comparative Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry of QX-like, Massachusetts and 793/B Serotypes of Infectious Bronchitis Virus Infection in Chickens. J Comp Pathol 2010, 143, 276. [CrossRef]

- Bóna, M.; Földi, J.; Dénes, L.; Harnos, A.; Paszerbovics, B.; Mándoki, M. Evaluation of the Virulence of Low Pathogenic H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus Strains in Broiler Chickens. Vet Sci 2023, 10, 671. [CrossRef]

- Okino, C.H.; Mores, M.A.Z.; Trevisol, I.M.; Coldebella, A.; Montassier, H.J.; Brentano, L. Early Immune Responses and Development of Pathogenesis of Avian Infectious Bronchitis Viruses with Different Virulence Profiles. PLoS One 2017, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rüger, N.; Sid, H.; Meens, J.; Szostak, M.P.; Baumgärtner, W.; Bexter, F.; Rautenschlein, S. New Insights into the Host–Pathogen Interaction of Mycoplasma Gallisepticum and Avian Metapneumovirus in Tracheal Organ Cultures of Chicken. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Maina, J.N. A Critical Assessment of the Cellular Defences of the Avian Respiratory System: Are Birds in General and Poultry in Particular Relatively More Susceptible to Pulmonary Infections/Afflictions? Biological Reviews 2023, 98, 2152–2187. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.L.; Kao, D.J.; Colgan, S.P. Neutrophils and the Inflammatory Tissue Microenvironment in the Mucosa. Immunol Rev 2016, 273, 112. [CrossRef]

- Blood and Circulatory System Diseases of Poultry. CABI Compendium 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pabst, R. The Bronchus-Associated-Lymphoid Tissue (BALT) an Unique Lymphoid Organ in Man and Animals. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger 2022, 240, 151833. [CrossRef]

- Bezuidenhout, A.; Mondal, S.P.; Buckles, E.L. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Study of Air Sac Lesions Induced by Two Strains of Infectious Bronchitis Virus. J Comp Pathol 2011, 145, 319. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).