1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, cancer is the second leading cause of death globally, highlighting the urgent need to predict responses to anticancer drugs. Various databases, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [

1], the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [

2] and the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) [

3], aim to comprehensively study genomic changes and catalog genetic mutations involved in human cancer through genotype-phenotype analysis technologies. While these initiatives provide a substantial amount of publicly accessible data, the heterogeneity within and between tumors makes research a complex and exhaustive process. Thus, the development of novel gene-drug mapping tools is crucial for identifying potential cancer biomarkers and drug targets, facilitating the drug discovery process and reducing the experimental workload.

Predicting the efficacy of anticancer drugs is a formidable challenge due to the need to integrate diverse data types, including genomic profiles, therapeutic intervention, and clinical characteristics and outcomes. The outcomes of drug therapy can be unpredictable, ranging from beneficial to toxic, and are largely driven by the tumor’s molecular profile [

4]. Responses to anticancer drugs can be influenced by both germline and acquired somatic mutations, as well as the status of gene expression and signaling pathways [

5,

6,

7]. This suggests that therapies targeting an individual’s genomic landscape are more effective than one-size-fits-all approaches. Recent advances in high-throughput drug screening, along with the availability of pharmacological and omics data (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic), have paved the way for identifying genetic biomarkers associated with treatment responses [

8]. These datasets have helped assess the sensitivity of many compounds including FDA-approved drugs in vitro and have enabled collective analysis of drug sensitivity and gene expression data to uncover novel gene-drug relationships [

6]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that machine learning models can achieve high accuracy in predicting drug activity against cancer cell lines [

9,

10]. However, they are all still in digital modeling phase far from clinical application.

Despite advancements in genomics-based drug sensitivity analysis, the practical application of genomic profiling for selecting appropriate drugs remains limited. The breakthrough PGA technology offers a novel method to predict drug sensitivity through personalized gene expression signatures [

6]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and only study to validate predicting patients’ sensitivity to the existing ~700 anticancer drugs using gene activation patterns derived from individual patients.

The majority of lung cancers (~85%) are grouped broadly as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In this heterogeneous class, the prognosis is particularly poor when cancer has spread to contralateral lymph nodes (Stage IIIB) or distant sites (Stage IV). The five-year survival rate drops dramatically—from 61% in earlier stages (IA-IIA) to just 6% in advanced stages [

11]. Since more than half of new cases are diagnosed at the metastatic disease stage, effective treatment in this setting is crucial. The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology recommend biomarker testing for eligible patients with metastatic NSCLC, if clinically feasible, to identify the most appropriate treatment options [

12]. However, there is limited information on whether and to what extent real-world clinicians have adopted these recommendations and altered the treatment of advanced NSCLC patients.

To further validate PGA technology in a real-world setting, we explored a reality check and the extent to which a NSCLC patient’s tumor response to multiple approved and experimental drugs (or drug efficacies) can be predicted based on the patient’s gene expression profile obtained through targeted transcriptomic profiling. Mapping patient-specific gene signatures to drug efficacies is highly transformative, as it paves the way for the transcriptomic characterization of treatment responses. This approach also has the potential to exclude certain drugs from being used in a patient’s treatment based on his/her functional genomic profile. In this study, PGA LUNG test results were compared to the current treatment trends in NSCLC, as the systematic review of publications and TCGA databases captured the evolving treatment patterns in the US.

3. Results

3.1. A Revolutionary Gene-to-Drug Technology

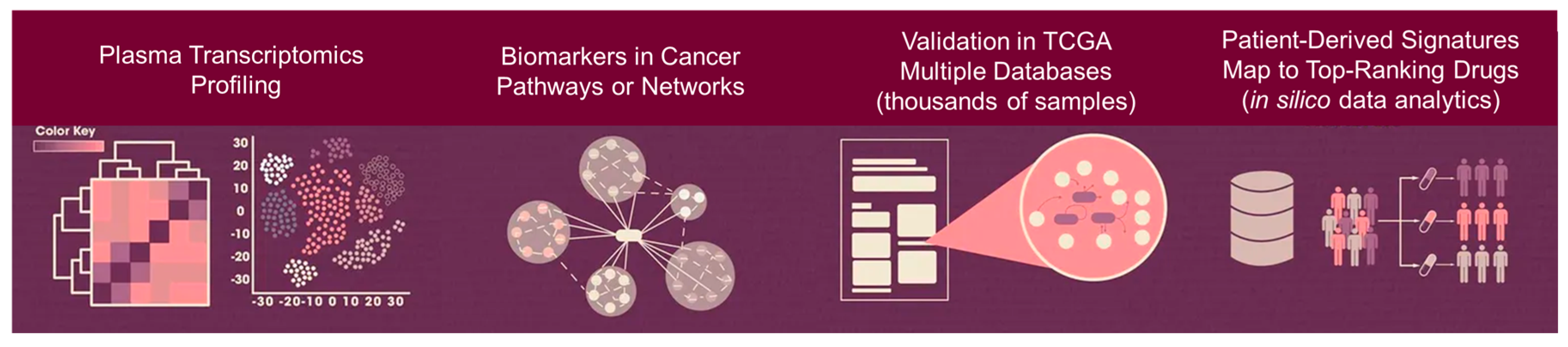

Our main goal was to use a patient-derived gene expression signature, coupled with in silico computational analytics, to predict drug efficacy/response for individual patients with cancer. An overview of the breakthrough gene-to-drug technology PGA (Patient-derived Gene expression-informed Anticancer drug efficacy) was shown in

Figure 1 [complete development and technical details were published in reference 6]. PGA performed consistently as the best predictor, with the added advantage of being highly computationally efficient, which is crucial for accurate gene-drug mapping. Furthermore, our data demonstrated that blood-based transcriptomic profiling can capture far more information about tumor microenvironment and immune cell interaction, than may have been previously appreciated beyond tumor mutations. Leveraging advanced liquid biopsy knowhow and disruptive technologies, we have maximized the PGA’s panel capacity enabling a high payload capacity for both tumor and non-tumor microenvironment biomarkers. The system integrates a real-time patient testing that allow it to establish the patient’s gene expression signature with precision–meaning the drug screening and mapping then can be made digitally, connected with data sources and merged to the reporting system. A laboratory can offer multiple PGA tests for different cancer types e.g., PGA LUNG, PGA BREAST and PGA PANCREATIC. With this diverse biomarker detection capability, PGA is capable of making accurate drug efficacy/response prediction following thorough interrogation of ~700 existing cancer drugs, either approved, in clinical trial or investigational.

The PGA’s ability to report out multiple classes, top-ranking cancer drugs from a single run, as opposed to the traditional one-class-of-drugs-per-test approach (i.e., companion diagnostics or biomarker testing for targeted therapy or immunotherapy), represents a major breakthrough: a single system for a wide variety of cancer drugs and combinations. The PGA test is particularly suited for cancer patients who are not qualified for precision therapy or have refractory, metastatic, relapsed disease or when the standard of care has exhausted. It greatly enhances alternative treatment options and provides flexibility with personalized drug selection.

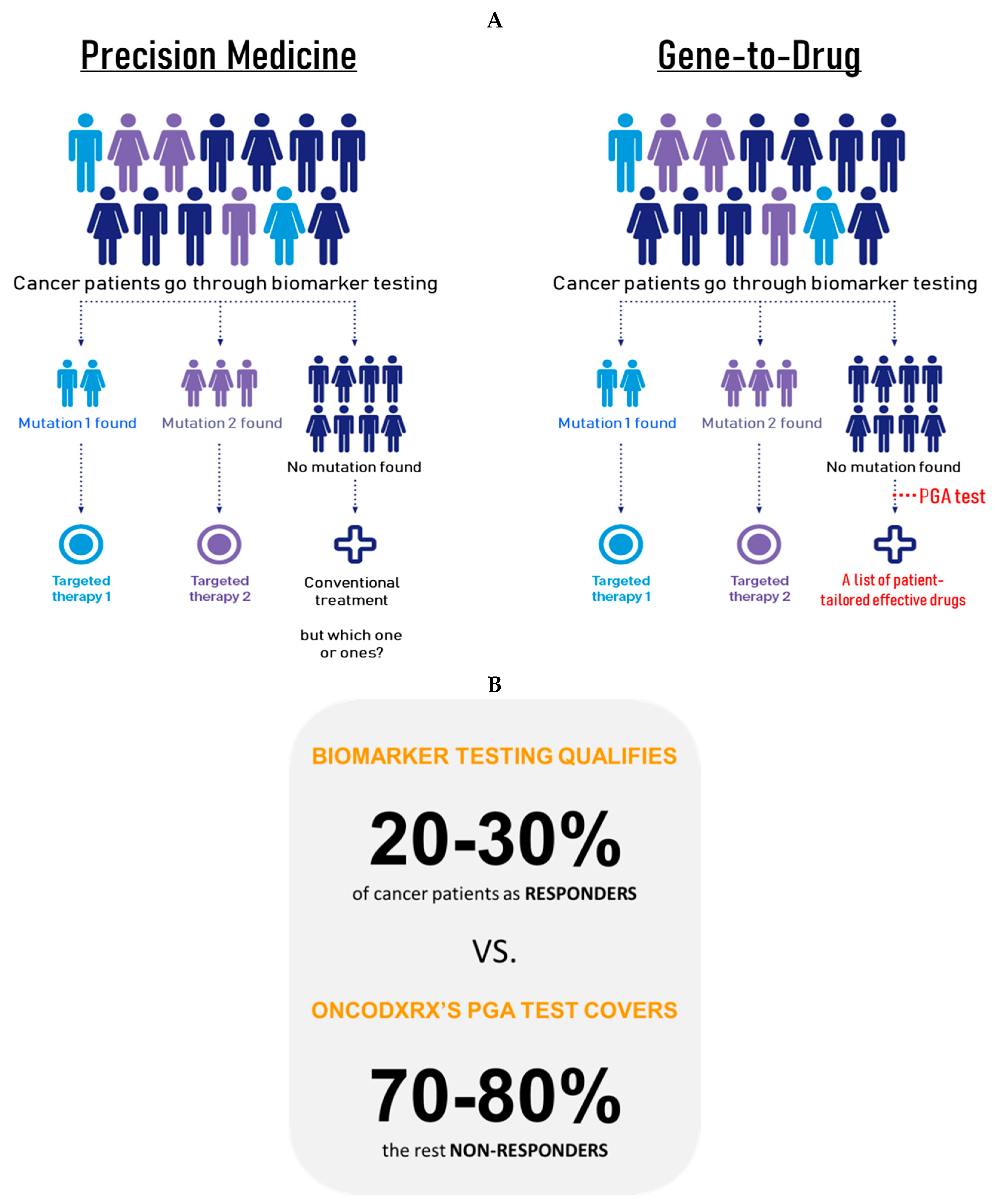

Both the PGA and biomarker testing (or companion diagnostics) offer distinct advantages, making them formidable technologies in their own right. The biomarker testing with its NGS-informed targeted therapy features, advanced bioinformatics, and cutting-edge tumor genome profiling systems, excels in modern, networked clinical decision-making. Meanwhile, the PGA, known for its versatility, quick turnaround, low cost, and powerful drug efficacy/response prediction capabilities, remains a patient-tested gene-to-drug technology capable of screening all existing cancer drugs in a single run.

While the biomarker testing and companion diagnostics, have long been a symbol of precision medicine, its limitations are becoming increasingly apparent. The lack of full-spectrum patient coverage puts biomarker testing and precision therapy at a significant disadvantage in the clinical reality where they can only qualify 20-30 percent of cancer patients while benefiting only 10-20 percent of patients (15). Without targeted therapy, the rest 70-80 percent non-responders would be vulnerable to the lacking of drug efficacy/response prediction tool, and therefore limiting treatment options (

Figure 2). Although targeted therapy remains effective in many scenarios, the benefit gap between responders and non-responders is growing. The rapid advancements in tumor clonal evolution and disease progression, including low response rate, drug resistance, metastasis and relapse, are making the situation more dire.

These situations have shifted the balance of power in the fight against cancer, and for the first time since first targeted drug approval, the revolution in precision medicine is being questioned. Precision oncology, in particular, is feeling the strain as the fleet of biomarker-targeted drugs—good though they are—lacks the therapeutic edge or diversity to benefit the entire patient population and fails to deliver their promise of no patient left behind. Most significantly, in the event of therapeutic exhaustion, clinicians will struggle to sustain any treatment plans beyond standard of care.

For precision diagnostic laboratories, the decision to potentially implement PGA could mark a significant expansion in its precision treatment selection capabilities, integrating it with current precision oncology testing workup. On the other hand, the biomarker testing, already in service with some molecular laboratories, continues to be a reliable and effective assay, offering a proven platform tailored to patients’ clinical needs. Yet, here is the real-life situation of today’s precision oncology biomarker testing: Apart from the few glaringly obvious actionable mutations, most end up receiving the blanket “mutation not detected” label, effectively leaving patients without any more treatment answers than when they came into the clinic to be sequenced as precious time ticks away.

Much more than a laboratory developed test, PGA offers a real-time, gene-to-drug mapping capability. The platform can smoothly integrate a patient’s own gene signature, enhancing and improving therapeutic efficacies and responses. Decision-making time is shortened from weeks down to days – which could save lives by giving early warnings and actionable options to patients sooner than later. Designed to benefit the patients who are not responding to current precision medicine, PGA marks a significant development of technology innovation into a transformative system aligned with modern clinical requirements.

3.2. Personalized Drug Efficacy/Response Results

We performed the PGA LUNG test in NSCLC patients through a pilot study to identify the top-ranking drugs for each patient. PGA LUNG classified drug responses as excellent, good and fair based on the confidence levels of 95%, 90% and 80% of Z-scores, respectively. As shown in

Table 1, for the five representative patients PGA LUNG predicted positive drug responses including cisplatin, oxaliplatin, paclitaxel, docetaxel along with irinotecan, topotecan, gemcitabine as well as 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide and temozolomide, all of which are very common chemotherapy drugs used to treat NSCLC. Similarly, some targeted therapy drugs approved by FDA for NSCLC were also picked up by PGA LUNG such as erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, osimertinib, cetuximab and trametinib, suggesting that PGA LUNG could enrich for drug responders, regardless of any known actionable mutations.

Additionally, PGA LUNG predicted efficacies of other cancer drugs that could potentially be used as off-label or for drug repurposing (repositioning) like PARP and HDAC inhibitors among others. Drug repurposing or repositioning is a method for identifying new therapeutic uses of existing drugs. Repositioning potent candidate drugs in NSCLC treatment is one of the important topics in personalized medicine. A recent meta-analysis suggested that PARP inhibitor-containing regimens can improve overall survival, particularly in NSCLC [

16]. While HDAC inhibitors are not highly efficacious as single agents for the treatment of NSCLC, the results of early phase clinical trials utilizing combination strategies have been encouraging, especially the combination with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors [

17].

The current study showcased PGA LUNG’s drug repurposing capability to identify candidate drugs to treat NSCLC patients. Our results here showed that the PGA LUNG test, derived from a patient’s own gene signature, have superior power to predict drug efficacy/response of a full spectrum of cancer drugs from standard-of-care to off-label, in contrast to other one-model-one-drug deep learning computational algorithms.

3.3. Treatment Trends for NSCLC in Archived Datasets and Real World

The TCGA database searches identified 1,145 records that reported treatment patterns in NSCLC patients. Of these, beside radiotherapy 286 cases reported on platinum-based therapies, followed by 71 cases with paclitaxel, 66 cases with pemetrexed, 56 cases with gemcitabine and 53 patients with docetaxel (

Table 2). Approximately 24% of patients were deceased while 62% are still alive. The majority of the patients were in the 45-85 age range, their cancers were localized and have not metastasized to other organs (M0/N0 stages). Chemotherapy was the most common first-line treatment among this cohort of NSCLC patients in the TCGA databases. NSCLC is the most common type of epithelial lung cancer, often diagnosed after 40% of lung tissue invasion. According to the World Health Organization, 30% of NSCLC cases can be cured if detected and treated early. Currently, treatment decisions rely heavily on genomic alterations and mutations. Achieving optimal outcomes requires considering available therapeutics in current anticancer approaches to enhance quality of life and treatment results for NSCLC patients. Importantly, PGA LUNG proposed drug list was in agreement with the treatment trends in the TCGA databases.

The choice of treatment for NSCLC in real world depends on several factors, including tumor grade, size, location, lymph node status, overall patient health, and lung function (

Table 3). For Stage 0 NSCLC, surgery is typically curative, with no need for chemotherapy or radiation therapy. For Stage I NSCLC, surgery remains the primary treatment option, and postoperative radiation therapy or adjuvant chemotherapy may reduce cancer recurrence. In Stage II NSCLC, surgery may be followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy. Initial treatment for Stage IIIA NSCLC often involves a combination of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or surgery, supplemented by immunotherapy. For patients with specific EGFR gene mutations, adjuvant therapy with the targeted drug osimertinib may be considered. Stage IIIB NSCLC, which cannot be entirely removed by surgery, benefits from chemoradiotherapy and immunotherapy. Stage IVA or IVB NSCLC is more challenging to cure, but treatments such as surgery, photodynamic therapy, laser therapy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy can help relieve symptoms. Compared to best supportive care, platinum-based chemotherapy extends survival, improves symptom control, and enhances quality of life for patients with metastatic disease. For patients with advanced, incurable NSCLC, cisplatin-based combinations have shown improved survival rates. Combining platinum with newer agents such as vinorelbine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine, or irinotecan has proven more effective than older platinum-based combinations. For patients whose disease progresses during or after first-line therapy, single-agent docetaxel and pemetrexed are preferred second-line therapies. Pemetrexed has demonstrated comparable efficacy to docetaxel with a more favorable adverse-effect profile [

18]. For Stage IVB cancers that have metastasized throughout the body, cancer cells will be tested for specific gene mutations, including VEGF, KRAS, EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, RET, MET, and NTRK genes. If any of these genes are mutated, targeted therapy drugs like EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors will likely be the first line of treatment [

19].

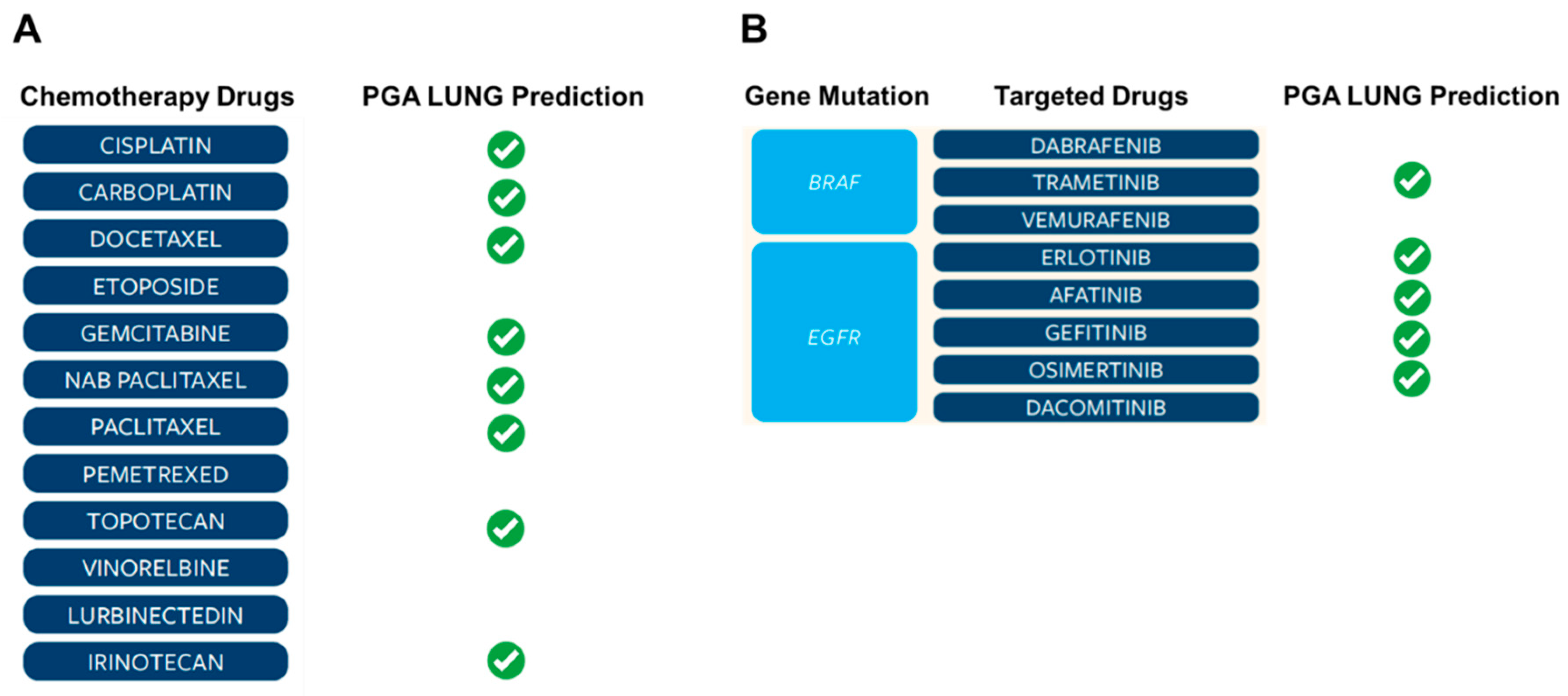

3.4. The Most Common Drugs Used to Treat NSCLC in Real World Were Picked Up by PGA LUNG Test

Real world data are becoming increasingly important in the evaluation of modern therapeutics. They allow for a pragmatic assessment of treatment patterns found in a variety of conditions and are particularly insightful in oncology where multiple lines of different treatments can be offered to the patient. Nevertheless, a growing literature describing the poor clinical outcomes among patients with NSCLC who experience progression on the front-line treatments, highlighting the large unmet need for additional treatment options that may improve survival in later lines of therapy. Therefore, clinical trials of novel agents that may offer benefit in this patient population are needed. Given the heterogeneous monitoring and treatment approaches in real-world clinical practice, it is noteworthy that certain PGA LUNG identified drugs, either chemotherapy or targeted therapy, were found to be frequently used in real world (

Figure 3). Together, the PGA LUNG test represents an unprecedented tool to support clinical decision-making of treatment selection.

3.5. PGA LUNG Provided Vital Insights for Combination Therapy

In the past decade, advances in molecular pathology have deepened our understanding of NSCLC’s pathophysiology and heterogeneity, leading to significant improvements in treatment methods. Despite the control provided by targeted therapies, drug resistance in tumors remains inevitable. To enhance treatment effectiveness, the development of combination therapies and a better understanding of resistance mechanisms are essential. Numerous clinical trials evaluating chemotherapy and targeted therapy agents are currently underway, and the results have been encouraging (

Table 4). Developing combination therapy is a complex endeavor that can greatly benefit from PGA LUNG that match patients’ transcriptional signatures with extensive drug efficacy/response data. This innovative gene-drug mapping approach allows for the identification of drugs and drug combinations tailored to target specific tumor pathways, networks or vulnerabilities in individual patients, making it highly suitable for developing personalized cancer treatment strategies.

Going forward, enhanced knowledge of predictive biomarkers and the development of combination therapies can provide the most effective treatments. Proper patient selection using PGA LUNG could be crucial for personalized oncological intervention, maximizing benefits, and reducing toxicities. Future improvements in patient survival are anticipated if resistance is addressed, suitable drugs or combinations of drugs are used, and side effects are minimized.

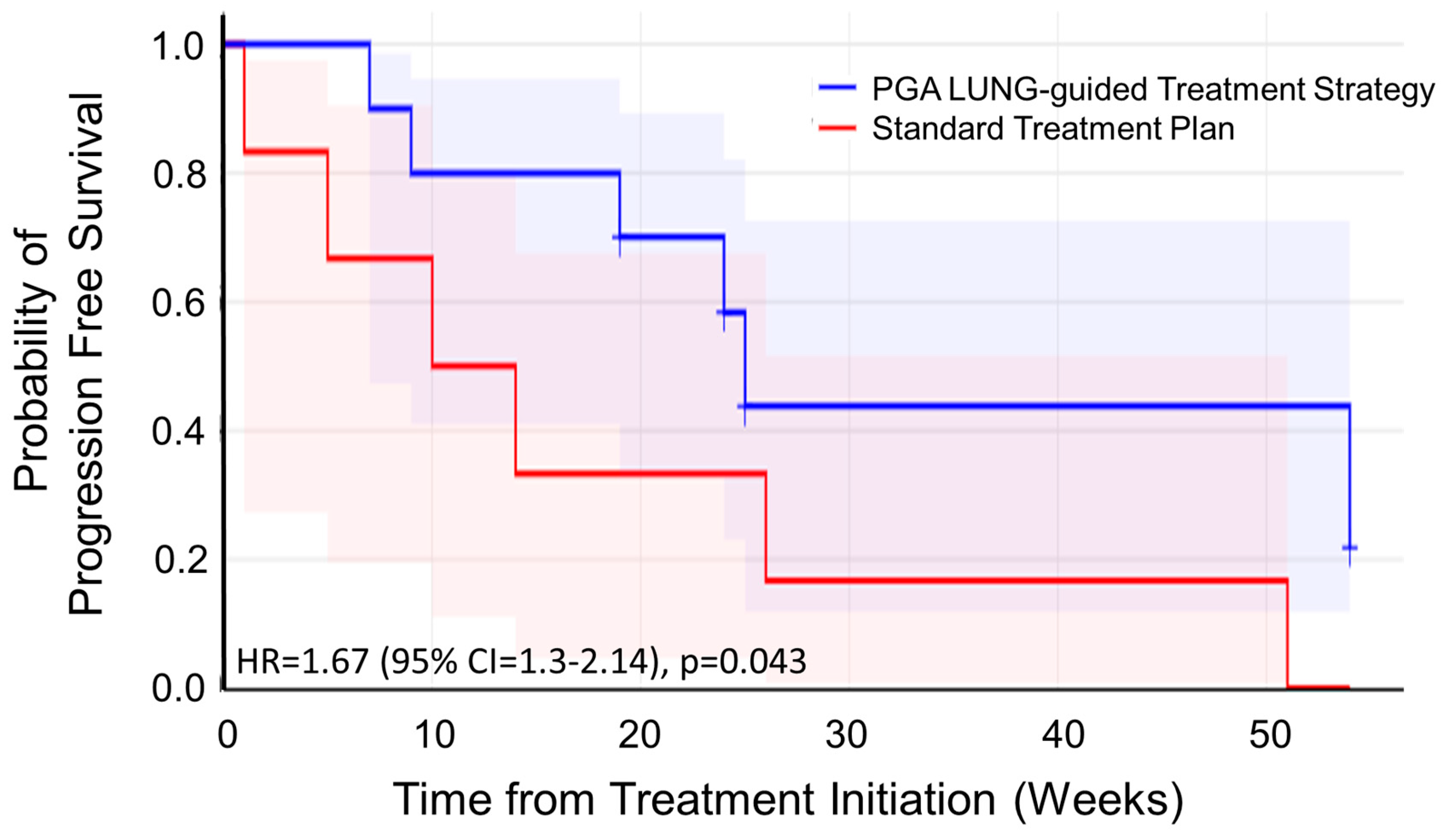

3.6. Clinical Performance of the PGA LUNG Test in A Small Real-World Trial

Progression-free survival (PFS) serves as the preferred endpoint in small-scale, short-duration oncology trials due to three key advantages over overall survival (OS) [

20]: (i) PFS events manifest earlier than OS events, enabling interim analysis within compressed trial timelines; (ii) Requires fewer participants and abbreviated follow-up versus OS studies, as progression events. It occurs more frequently than deaths and presents earlier in the disease trajectory, reducing trial costs by 30-50% and accelerating development cycles; (iii) PFS is less confounded by subsequent treatment lines, non-cancer mortality, providing a cleaner signal of the investigational therapy’s efficacy.

To evaluate clinical performance of PGA LUNG in a real-world setting, we analyzed 12 patients with recurrent/progressive lung cancer who have limited therapy options. Patients were prospectively stratified into two matched cohorts (placebo: n=6; experimental: n=6) balanced by age, gender, and disease stage. In the placebo group, patients received standard-of-care therapy without PGA guidance; while in the experimental cohort, patients went through PGA LUNG test and received PGA-informed treatment selection. The Kaplan-Meier method and a log-rank test were used to analyze the univariate discrimination of PFS as the primary outcome by demographic data, baseline clinical information and toxicities. Kaplan-Meier analysis in our small trial demonstrated significantly prolonged PFS (HR=1.67; 95% CI:1.3-2.14; p=0.043) in PGA LUNG-guided versus non-guided lung cancer patients (

Figure 4). These findings confirmed PGA LUNG’s clinical utility, showing a substantial survival impact in real-world settings.

4. Discussion

Cancer’s complexity arises from the intricate interplay of genetic and epigenetic factors, biological networks, compensatory mechanisms, and environmental influences, making it unlikely that each patient will respond similarly to the same drug(s). Over the past few decades, there has been a lack of new treatment mechanisms for cancer patients who do not respond to precision therapies, i.e., non-responders. This is largely because modern medicine has focused primarily on the development of target-based therapies. Even patients with the same cancer type need personalized treatments due to factors like genetic predisposition, lifestyle, and immune response. Therapeutic outcomes range from complete remission to treatment resistance, and cancer cells often develop drug resistance through genetic mutations, making therapy ineffective.

Today there are more than 60 companion diagnostics approved by the FDA, most of these in the field of oncology. Most drugs that are out there today will help a fraction of the patients that receive them; identifying the fraction that will respond to these drugs is incredibly important. Most companion/biomarker tests in the market today target a single biomarker, and therefore, lack the ability to tackle the vast heterogeneity seen across patients and within individual tumors. These constraints contribute to the fact that, even today, many patients who receive targeted treatments fail to respond to them. Therefore, it is utmost critical to getting a patient on the right drug as quickly as possible!

We have demonstrated a breakthrough technology, PGA LUNG, for the prediction of drug efficacy/response in NSCLC patients using patient-derived gene expression signature. First, we established a lung cancer-specific gene overexpression panel using liquid biopsy transcriptomic profiling. Following patient testing with data homogenization and filtering, the patient-unique gene pattern was used to map out the best fitting drugs from a library of ~700 cancer drugs, yielding a list of potential drugs predictive of excellent, good or fair responses.

PGA LUNG captured a statistically significant proportion of potentially effective drugs, regardless of standard-of-care or off-label and in all cases, results were consistent with those treatment trends in the TCGA databases, NCCN guidelines and real-world patients. Overall, our results here suggested that PGA LUNG created on patient’s own gene signature, can complement, or even surpass the performance of companion diagnostics biomarker testing. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a drug response prediction technology capable of this function has been described.

In NSCLC, standard treatments yield poor outcomes, except in the most localized cases. Newly diagnosed NSCLC patients are potential candidates for studies exploring new treatment methods. Surgery offers the most curative potential for this disease. Postoperative chemotherapy may further benefit patients with resected NSCLC. Radiation therapy combined with chemotherapy can cure a small number of patients and provide palliation for many. Prophylactic cranial irradiation may reduce brain metastases incidence, but there’s no evidence of a survival benefit, and its impact on quality of life remains unknown [

21]. In advanced-stage disease, chemotherapy or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase inhibitors provide modest improvements in median survival, though overall survival remains poor [

22].

Chemotherapy has led to short-term improvements in disease-related symptoms for patients with advanced NSCLC. Numerous clinical trials have evaluated the impact of chemotherapy on tumor-related symptoms and quality of life. Collectively, these studies indicate that chemotherapy can manage tumor-related symptoms without negatively affecting overall quality of life [

23,

24]. However, further research is needed to fully understand its impact on quality of life. Generally, older patients who are medically eligible and have good performance status experience the same benefits from treatment as younger patients.

The discovery of gene mutations in lung cancer has paved the way for molecularly targeted therapies, improving the survival rates of certain patients with metastatic disease [

25]. Specifically, genetic abnormalities in the EGFR, MAPK, and PI3K signaling pathways in subsets of NSCLC can define mechanisms of drug sensitivity and resistance, both primary and acquired, to kinase inhibitors. EGFR mutations significantly predict an enhanced response rate and progression-free survival with EGFR inhibitors. ALK fusions with EML4 and other genes, found in about 3% to 7% of unselected NSCLC cases, respond well to ALK inhibitors like alectinib. The MET oncogene, encoding the hepatocyte growth factor receptor, is linked to secondary resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Recurrent ROS1 gene fusions, observed in up to 2% of NSCLCs, respond to crizotinib and entrectinib. NTRK gene fusions, present in up to 1% of NSCLCs, can be treated with TRK inhibitors such as larotrectinib and entrectinib [

19,

26].

A systematic review of the TCGA databases and real-world statistics revealed that the primary chemotherapeutics used in NSCLC are platinum analogs (cisplatin and carboplatin), vinca alkaloids (vinorelbine, vinblastine, vindesine), etoposide, gemcitabine, pemetrexed, topoisomerase I inhibitors (irinotecan, topotecan), and taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel). While chemotherapy monotherapy is less commonly employed as a first-line treatment, it is most frequently administered to elderly patients aged 65 years and above. Conversely, targeted therapies, including TKIs such as gefitinib, erlotinib, afatinib, and osimertinib, showed the highest utilization as first-line treatments [

27,

28].

With the recent expansion of personalized treatment options for NSCLC, the adoption of immunotherapy has steadily increased in frontline treatment within real-world practice. Most patients receiving immunotherapy were treated with pembrolizumab, either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy. Combination therapy is expected to grow in popularity over the coming years. For second-line treatment, unspecified chemotherapy regimens remained the primary therapy in studies, closely followed by chemotherapy monotherapy.

In this study, the PGA LUNG test successfully passed a reality check and demonstrated its accuracy by aligning its results with TCGA data and real-world treatment trends in NSCLC. PGA LUNG goes beyond merely predicting drug responses; it enables the identification and ranking of the most effective drugs, whether approved, in clinical trials, or investigational. Our findings also indicated that real-world treatment patterns shift as new therapies are introduced and as US treatment guidelines evolve. Clinical practice treatment decisions appear more adaptable to therapies designed to target cellular signaling and/or modulate the immune microenvironment as the PGA LUNG test does.

The “tumor vulnerability” biomarkers included in PGA LUNG highlighted key genes and signaling pathways that may play significant roles in the mechanisms of action of various lung cancer drugs. These findings suggested that our gene-to-drug mapping technology can generate biologically relevant genes and pathways, enhancing the understanding of mechanisms underlying drug efficacy and response. Furthermore, it may provide additional combinatorial therapeutic strategies to overcome certain drug resistances.

A significant strength of the PGA LUNG test lies in its robust, streamlined, and reproducible approach to mapping, identifying, and ranking the best cancer drugs for individual patients. It outperforms other in silico deep-learning models in terms of the number of drugs for which it can distinguish between resistant and sensitive tumors as well as prediction accuracy. Notably, while all in silico digital training models are still in the development stage and far from clinical application, PGA LUNG has shown promising results ready for its prime time in clinical settings.

By incorporating patient-specific gene signatures, PGA LUNG extracts more precise drug efficacy/response information. Furthermore, it highlights the efficacy of certain off-label cancer drugs, such as inhibitors of PARP (poly ADP-ribose polymerase), MEK (mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase), and HDAC (histone deacetylase). Despite significant advancements in surgical, radiological, chemical and immunological approaches that have improved cancer treatment outcomes, drug regimen remains a key therapeutic strategy. However, its clinical efficacy is often limited by drug resistance and severe toxic side effects, highlighting the critical need for novel cancer therapeutics. One promising strategy gaining attention is drug repurposing, which involves identifying new applications for existing, clinically approved drugs. This approach offers several advantages in cancer treatment, as repurposed drugs are typically cost-effective, proven to be safe, and can expedite the drug development process due to their established safety profiles. In this regard, PGA LUNG could provide an unprecedented and unmatched power for cancer drug repurposing or re-positioning, advancing the field of precision medicine and showcasing its potential to provide more effective and less toxic therapeutic options for cancer patients.

PGA LUNG testing results demonstrated exceptional performance in predicting clinical drug efficacy/response, aligning with real-world treatment patterns and potentially having a profound impact on patient care. For example, predicting therapeutic efficacy/response in vitro is significantly less costly and time-consuming than conducting large clinical trials. Additionally, in vitro patient testing is typically conducted under controlled experimental conditions, leading to greater accuracy. The ability to test a larger number of patients with greater accuracy, lower costs, and faster turnaround times can enhance statistical power compared to in vivo animal models, which rely on smaller sample sizes and often yield noisy clinical response data. Overall, the PGA LUNG approach represents a revolutionary breakthrough in personalizing drug treatment.

There is no limit to the number of drugs that could be mapped out against a patient’s gene expression profile. With PGA LUNG, predictive efficacies of all existing anti-cancer compounds can be obtained, meaning that given a liquid biopsy, it would be game-changing and disruptive to use this approach to estimate response to every drug prior to any course of clinical treatment. The affordability and accessibility of PGA LUNG makes it feasible to incorporate this technology into standard of care.

Our findings have also significant implications for drug development, where the PGA approach could be utilized to identify likely drug responders before conducting clinical trials. There is growing interest in developing drugs alongside companion diagnostic tests. While the benefits of identifying potential drug responders are clear, developing accurate biomarkers without exposing the drug to patients is challenging. PGA LUNG holds tremendous potential as a companion diagnostic, especially for patients unresponsive to precision therapy. Additionally, there is a clear ethical advantage, as this diagnostic method can be developed without exposing potentially unresponsive patients to toxic drug candidates.