1. Introduction

The Royal Irrigation Department (RID), through the Regional Irrigation Office 3 in Phitsanulok Province, has implemented the Bang Rakam model project, focusing on strategic water management in lowland areas. Each year, the project adjusts the planting schedule for rain-fed rice farming to begin in April and complete harvesting by July, allowing the area to function as a temporary flood retention zone during the rainy season. The Bang Rakam model area is capable of storing approximately 400–500 million cubic meters of water; however, this capacity is estimated based on the experience of irrigation officials and local residents, as precise flood volume measurements in such an expansive area remain challenging [

1]. Current flood monitoring tools in the region still exhibit discrepancies in measuring flood volume, leading to delays in flood warnings and inefficiencies in emergency response due to lack of real-time flood data [

2]. Recent studies emphasize the importance of accurate flood volume assessment and real-time data collection in flood-prone regions[

3,

4,

5,

6].

A field survey conducted by the Irrigation Region 3 Office during the 2020 rainy season revealed that local residents were significantly affected by the lack of reliable flood data. This deficiency led to poor agricultural and aquaculture planning, including delays in seedling preparation and fishing activities, as farmers were unaware of the actual water situation[

7]. Furthermore, the lack of public participation in water management was in part due to the inaccessibility of flood data and monitoring technologies. Studies highlight that limited accessibility to real-time flood data hinders effective decision-making and planning, particularly in rural agricultural communities.

Currently, flood monitoring tools available in the region are costly, both in terms of procurement and maintenance, making large-scale deployment impractical [

8,

9]. To address this issue, the Regional Irrigation Office 3 developed a semi-automatic water level assessment tool based on closed-circuit television (CCTV) images. This system, referred to as Semi-GIC (Graphic Information Camera), relies on manual evaluation by personnel to determine water levels from CCTV footage [

10,

11,

12]. However, this semi-automated process is labor-intensive and dependent on staff availability, particularly during non-office hours, which limits the timeliness and efficiency of data collection. Research by [

13,

14,

15] show that IoT-based systems that use automation and artificial intelligence (AI) can solve these problems by needing less human work and allowing for constant, real-time flood monitoring[

16,

17,

18].

Given these challenges, this research focuses on improving water level monitoring accuracy using spatial data analysis techniques by integrating the Geospatial Information Systems (GIS) and the Internet of Things (IoT) [

19]. IoT-based flood monitoring systems, as demonstrated by[

17,

20], have proven to be highly effective in real-time water level tracking, allowing for timely alerts and improved disaster management[

21]. This study aims to develop a real-time flood monitoring and simulation system that integrates IoT sensors, GIS data, and raster processing techniques to enhance flood prediction, monitoring, and decision-making capabilities, ultimately addressing the limitations of existing flood management approaches

2. Materials and Methods

To effectively monitor flood dynamics in the Bang Rakam model area, this study integrates low-cost IoT-based water level sensors with a flood simulation model[

22]. The approach involves deploying sensors across multiple stations to collect high-frequency water level data, which is then processed and analyzed to generate spatial flood extent and depth maps[

23]. By combining sensor-based measurements with geospatial analysis, the system provides a cost-effective and automated alternative to traditional flood monitoring methods[

24,

25,

26]. The following sections detail the sensor deployment strategy and the flood model development process, describing the hardware components, data transmission methods, and analytical techniques used in this study.

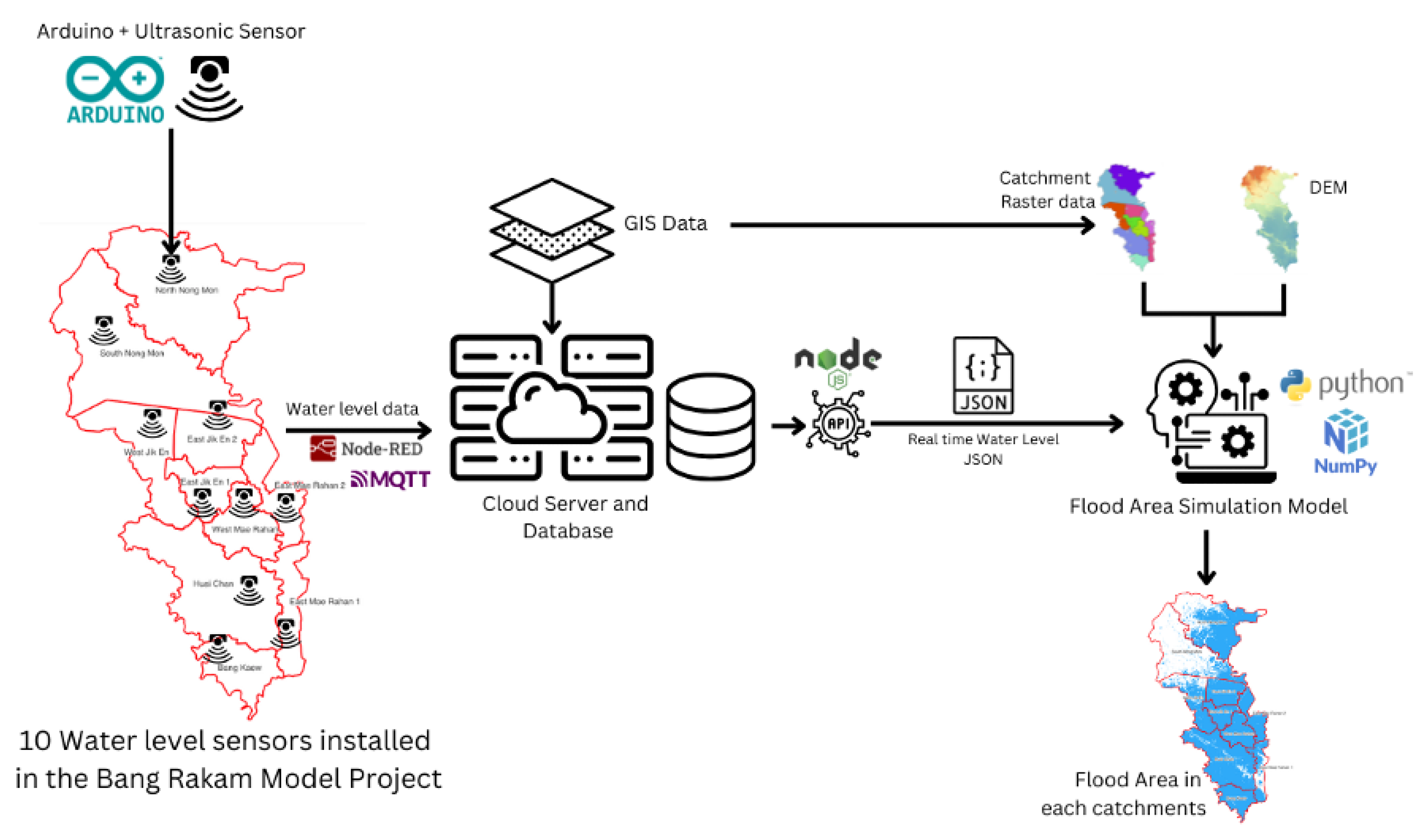

Figure 1 demonstrates the concept of this framework; 10 water level stations, coupled with Arduino and ultrasonic technology, have been installed in the Bang Rakam model area. These sensors collect water level data and send it to a cloud server using Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) protocol, which uses Node-RED for data management and API interaction[

27]. The cloud architecture saves and processes water level data at predetermined time intervals, sending JSON outputs to modeling applications. Python-based flood simulation models, powered by libraries like NumPy, combine GIS data, such as catchment raster data and DEM, with water level data. The produced models predict flood-prone areas in all catchments, resulting in flood-prone maps.

2.1. Study Area

The provinces of Sukhothai and Phitsanulok are extremely vulnerable to floods, especially in the Yom River Basin’s lowland regions. Because of the basin’s conical and twisting topography, water drainage is considerably slowed, which prolongs flooding throughout the rainy season. Excess water frequently overflows downstream from heavy rainfall in the upper Yom River Basin, causing significant flooding in Sukhothai province that affects both residential areas and agricultural grounds[

1].

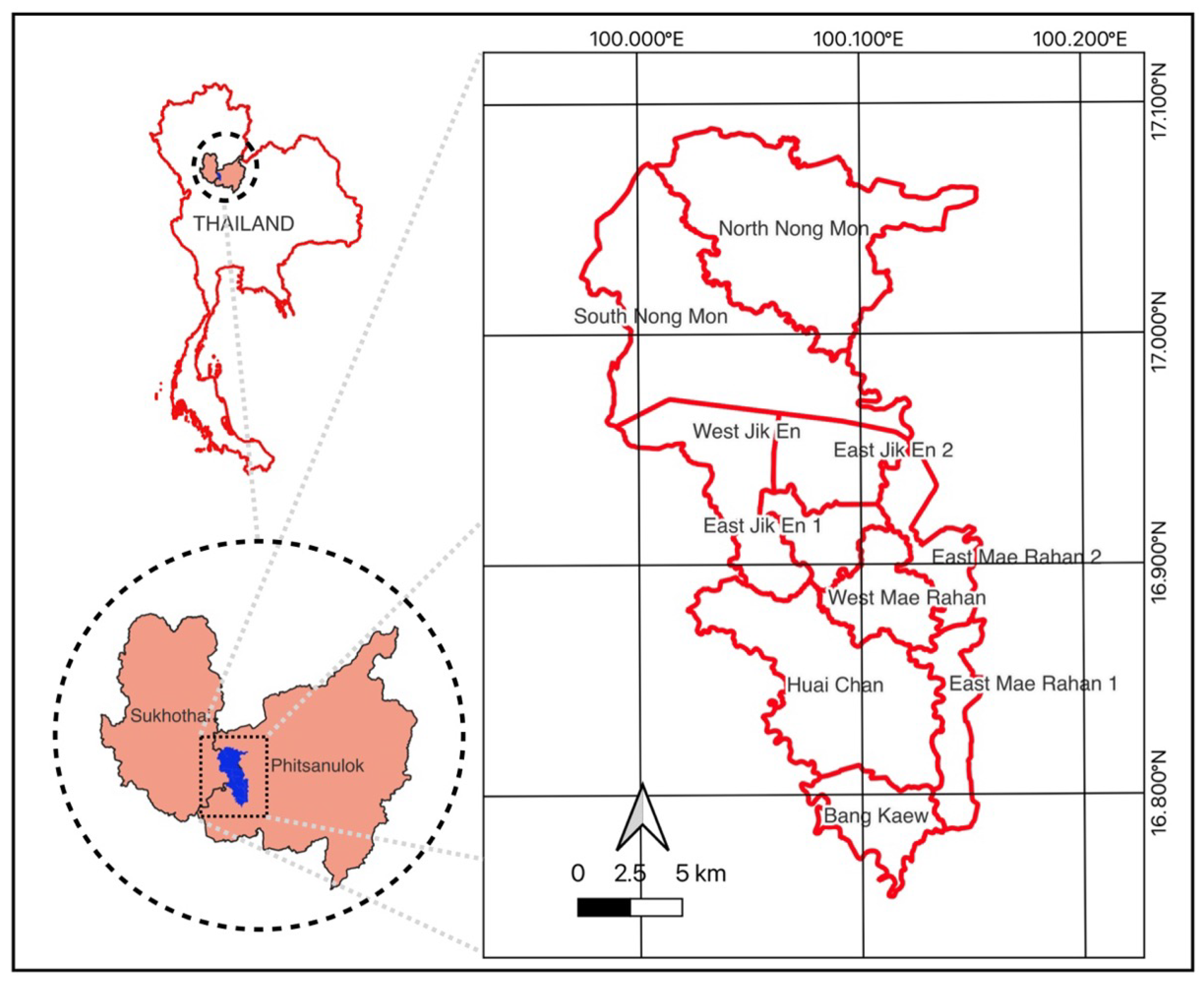

The Phitsanulok province’s Bang Rakam model area, depicted in

Figure 2, is a designated flood retention zone. Large tracts of low-lying farmland that are vulnerable to seasonal flooding and rice paddies make up the majority of this area’s agricultural landscape. The natural geography of the region helps to lessen the intensity of floods in downstream areas by temporarily storing floodwaters before they gradually drain into the Nan River system. The network of floodplains, reservoirs, and irrigation canals in the study area is essential for distributing and retaining water. For efficient flood assessment and management, it is crucial to comprehend the hydrological interactions between these water bodies since they affect the temporal and spatial changes in flood depth and duration.

2.2. Hardware Design and Implementation

The goal of developing and implementing a water level monitoring system is to provide a reliable and effective platform for precisely tracking water levels. Modern technologies like low-cost sensors for real-time data collecting, automation to lessen the need for manual work, and sophisticated geospatial analysis tools for efficient data processing and visualization are all integrated into this system [

24,

28]. The created system is to improve flood monitoring [

29], increase water management capabilities, and offer timely information for decision-making in lowland areas that are vulnerable by resolving current restrictions.

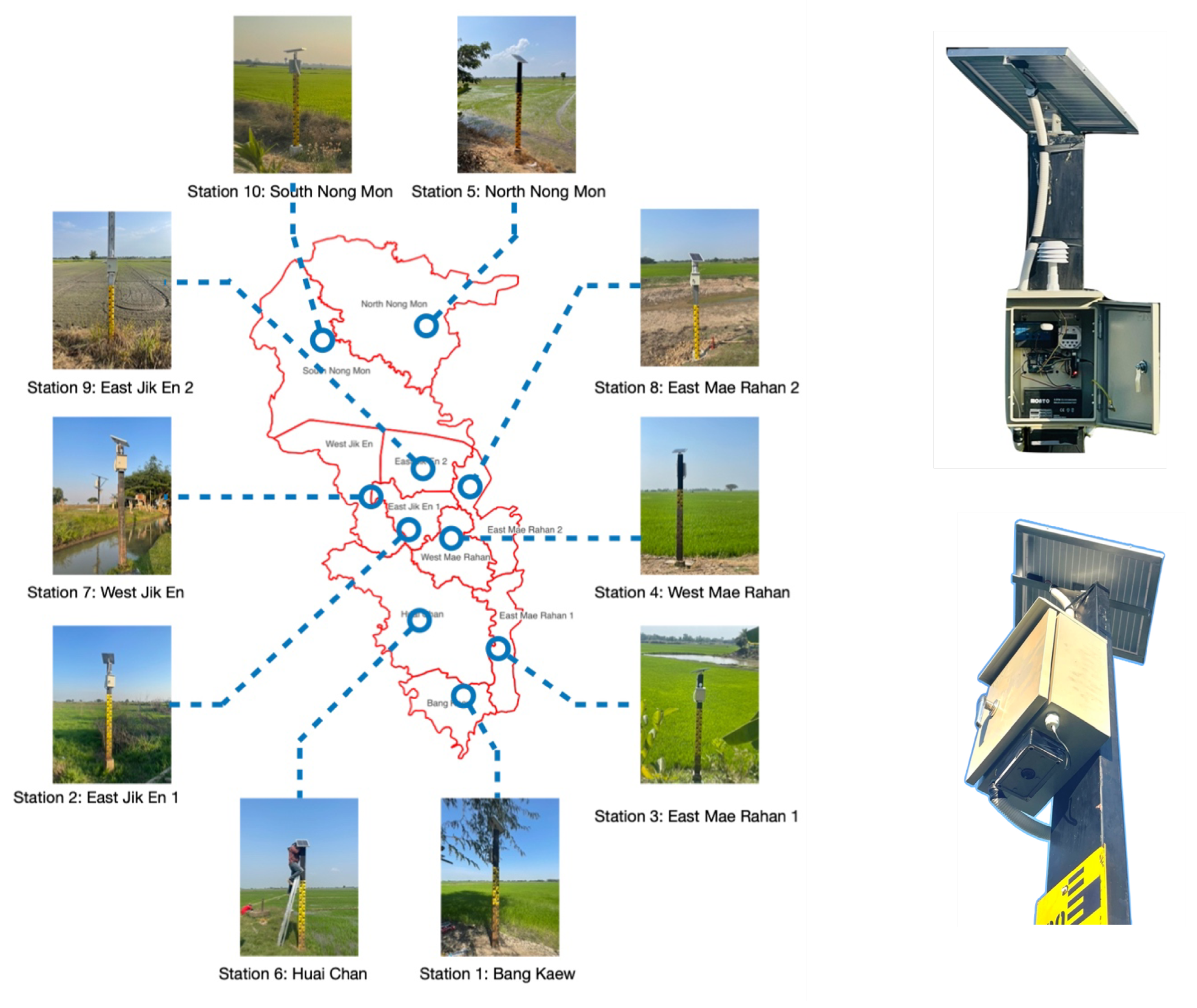

The creation of the real-time water level monitoring system, which makes use of the JSN-SR04T Ultrasonic Module, is shown in

Figure 3. This module is appropriate for outdoor applications because of its splash and moisture resistance construction. The sensor can identify objects and determine their distance from the sensor, which is between 20 cm and 4 m. With a working current of less than 8 mA, a probe frequency of 40 kHz, a resolution of 1 mm, a distance accuracy of ±1 cm, and a DC voltage of 3.0 to 5.5 V, it functions. Because of these features, the module is very dependable for precise and effective water level readings in real-time monitoring systems.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the sensor is combined with an Arduino Wemos D1 ESP8266 board, a Wi-Fi-capable board built around the ESP8266 chip. The Wemos D1 runs at 3.3 V and has the same design as the Arduino UNO. The board is controlled by the 32-bit CPU ESP8266 chip, which also has more flash memory than the Arduino UNO. With its eleven digital I/O pins and one analog input pin, it can be used in a variety of ways. A Micro-B USB cable can be used to connect the board. It is a great platform for IoT systems because of its Wi-Fi capability and support for MQTT communication, which allows it to effectively control outputs, read inputs, and manage interruptions [

30,

31]. This configuration allows for smooth data transfer between IoT devices and the central server in real-time via 3G signals supplied by Pocket Wi-Fi.

As seen in

Figure 4, all ten stations were placed in the Bang Rakam model area. For high-frequency water level monitoring, a sensor unit consisting of a JSN-SR04T ultrasonic sensor is placed 350 cm above the surface. The sensor was manually maintained once a week and included a waterproof glue covering to guard against damage from extended exposure to water. In order to avoid system freezes and guarantee smooth functioning, a timer was also built to reset the sensor on a regular basis. To reduce the possibility of equipment damage, all parts were kept inside a weatherproof enclosure that protected them from elements including sunshine, wind, and rain.

2.3. Real-Time Data Collection

Since the RID releases water into the area and diverts it out around this time every year, we began gathering data from the beginning of August until the second week of November. A real-time data transmission module that uses a 3G network and an Arduino Wemos D1 ESP8266 board to transmit data over the MQTT protocol to a central server. In order to ensure continuous functioning in remote locations, the complete system was powered by a solar panel coupled to a 12V battery. The sensor devices use the MQTT protocol to transmit data when they are connected to a pocket Wi-Fi network.

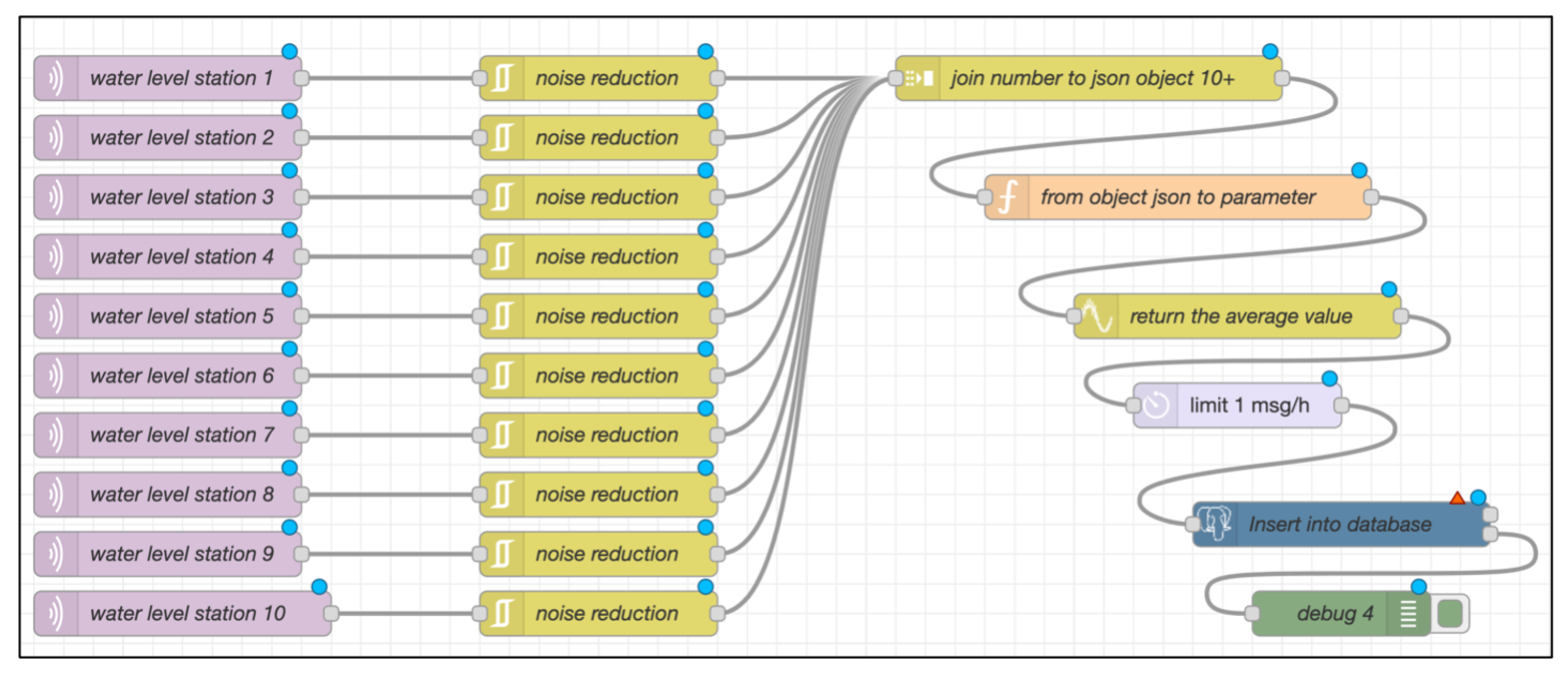

Figure 5 illustrates how Node-RED, which subscribes to MQTT, processes the data before sending it to the PostgreSQL/PostGIS database. Data transmission is planned to happen once daily while water is not yet arriving and once every hour when water is coming in. Spatial analysis techniques are used to further evaluate the data once it has been placed in the database.

2.4. Flood Simulation Model

A flood simulation model was created utilizing water level data obtained from ten sensor locations in the Bang Rakam model area. The system incorporates a variety of data sources, including real-time water level data from sensors, raster-based catchment area information, and DEM data [

4,

5]. These datasets are run via a simulation algorithm that predicts flood extent and depth in the selected catchment regions.

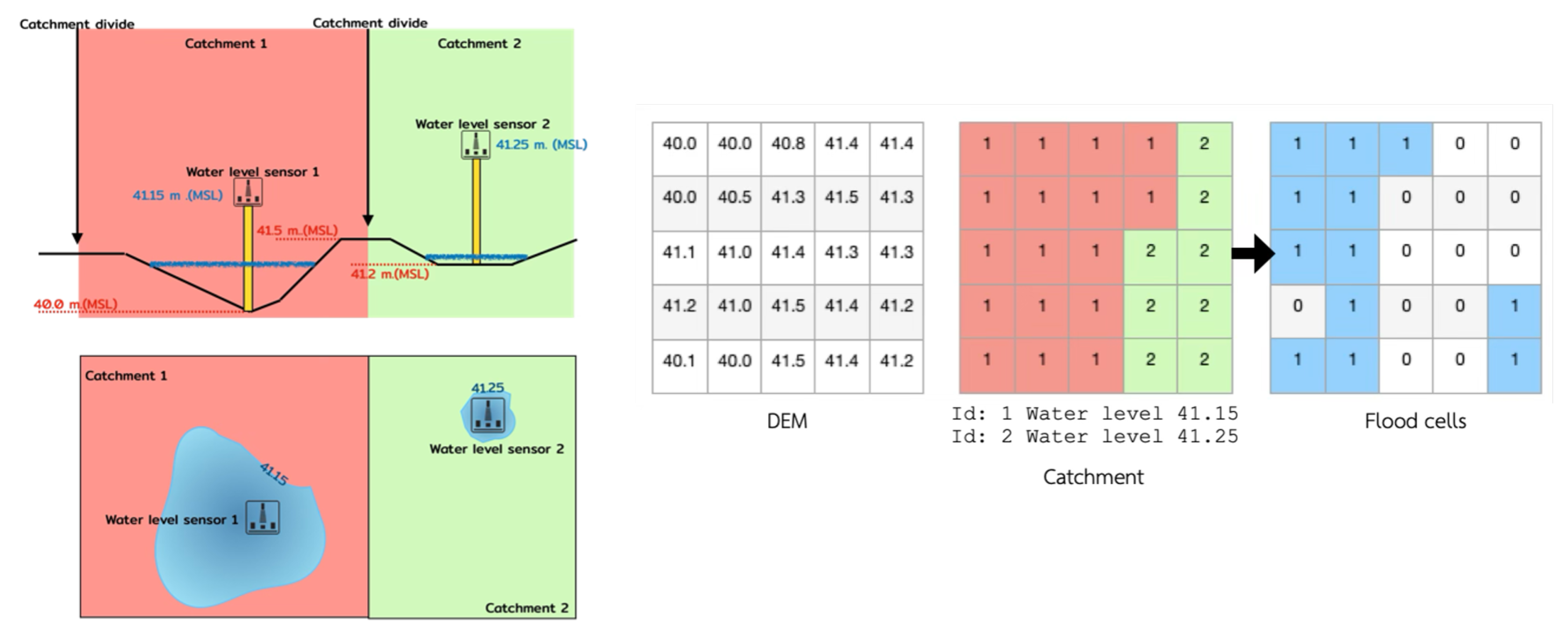

Figure 6 explains how to generate DEM and catchment area data in raster format to suit grid observations from 10 monitoring stations. The application examines this information by comparing DEM values for each grid cell to actual water levels. If a DEM cell value is less than or equal to the recorded water level, it is deemed flooded; otherwise, it remains dry. The simulation results are demonstrated by mapping the flooded areas, indicating flood extent using data collected from sensors.

The algorithm for Flood Area Simulation The following steps were created using raster-based processing[

3]:

Data Preparation: Gather raster-based catchment data with corresponding dimensions and DEM data.

Water Level Retrieval: Get data from 10 sensors about the water level in JSON format by retrieving it from the database. The simplest method for retrieving data from the server for additional analysis is to use the JSON format[

32,

33]].

Data processing: The DEM and catchment data are loaded as Numpy arrays using Python programming to do computations.

Flood Calculation: Depending on the level of each catchment region, designate a cell as flooded (1) if its DEM value is less than the sensor water level and as dry (0) otherwise.

Generating Results: Save the processed data in Geotiff format for display.

3. Results

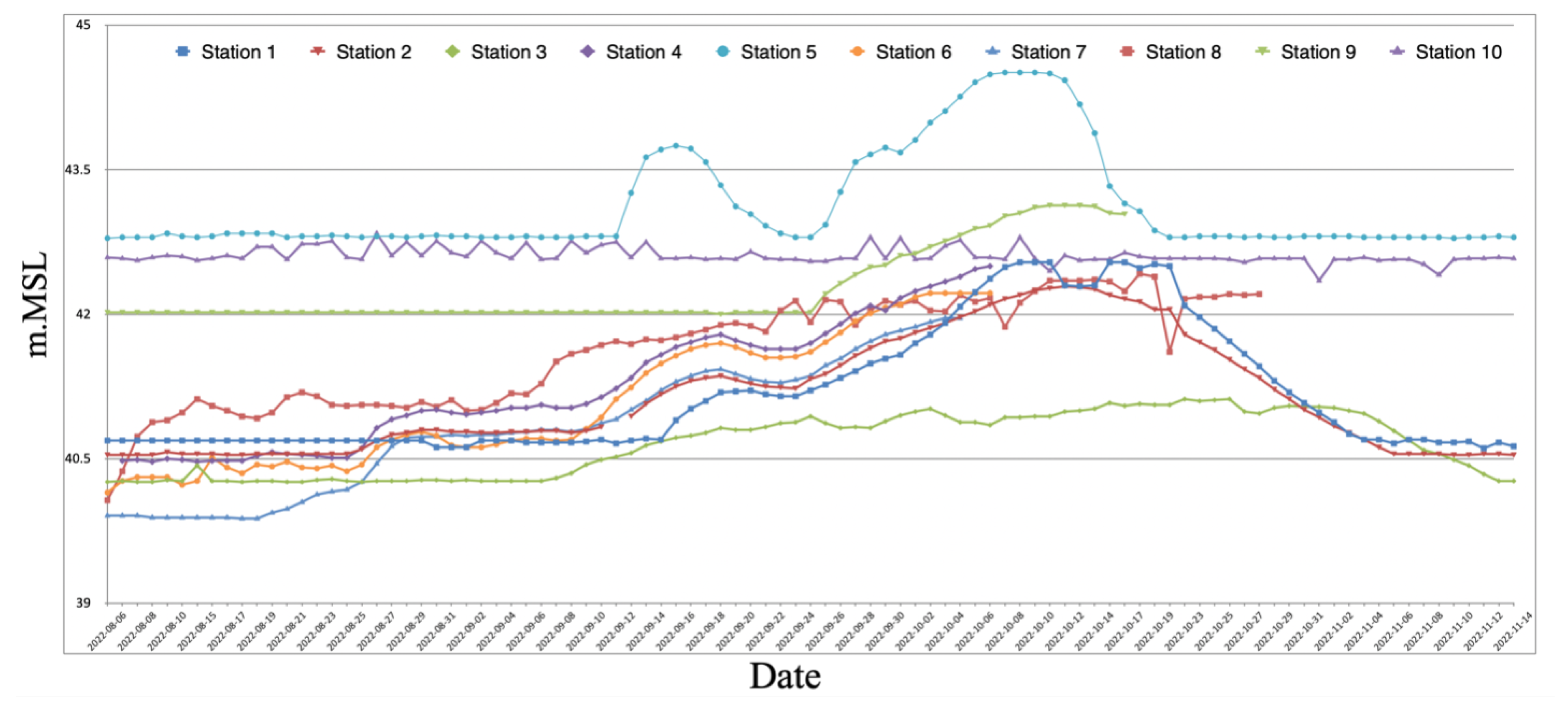

An overview of the daily water level readings and depth fluctuations obtained at every monitoring station in the Bang Rakam model region is given in

Figure 7. With recorded water levels ranging from 40 to 44 meters above mean sea level (m.MSL), the data show that overall water levels started to rise in the first week of September and then progressively dropped to near-normal levels between early and mid-November. With a maximum recorded water level of around 44.51 m.MSL and a ground height of about 42.81 m.MSL, Station 5 (North Nong Mon) is the highest elevation of the monitoring stations. With a highest recorded water level of 41.96 m.MSL and a ground height of 39.9 m.MSL, Station 7 (East Jik En) is situated at the lowest elevation. The disparities in flood behavior throughout the region are emphasized by these water level fluctuations.

Because there are ten different basins in the research area, the graph shows how the initial water levels before flooding vary in m.MSL. Users can monitor the data in real-time. Creating an appropriate flood model that takes into consideration the variations in water flow dynamics is made more difficult by this spatial diversity. Furthermore, the graph shows that the timing of water entry and outflow varies among basins, suggesting that drainage and flooding do not always happen at the same time. This demonstrates how intricate the water movement is in the Bang Rakam model and emphasizes the necessity of a thorough flood simulation to comprehend and forecast flood behavior in the area.

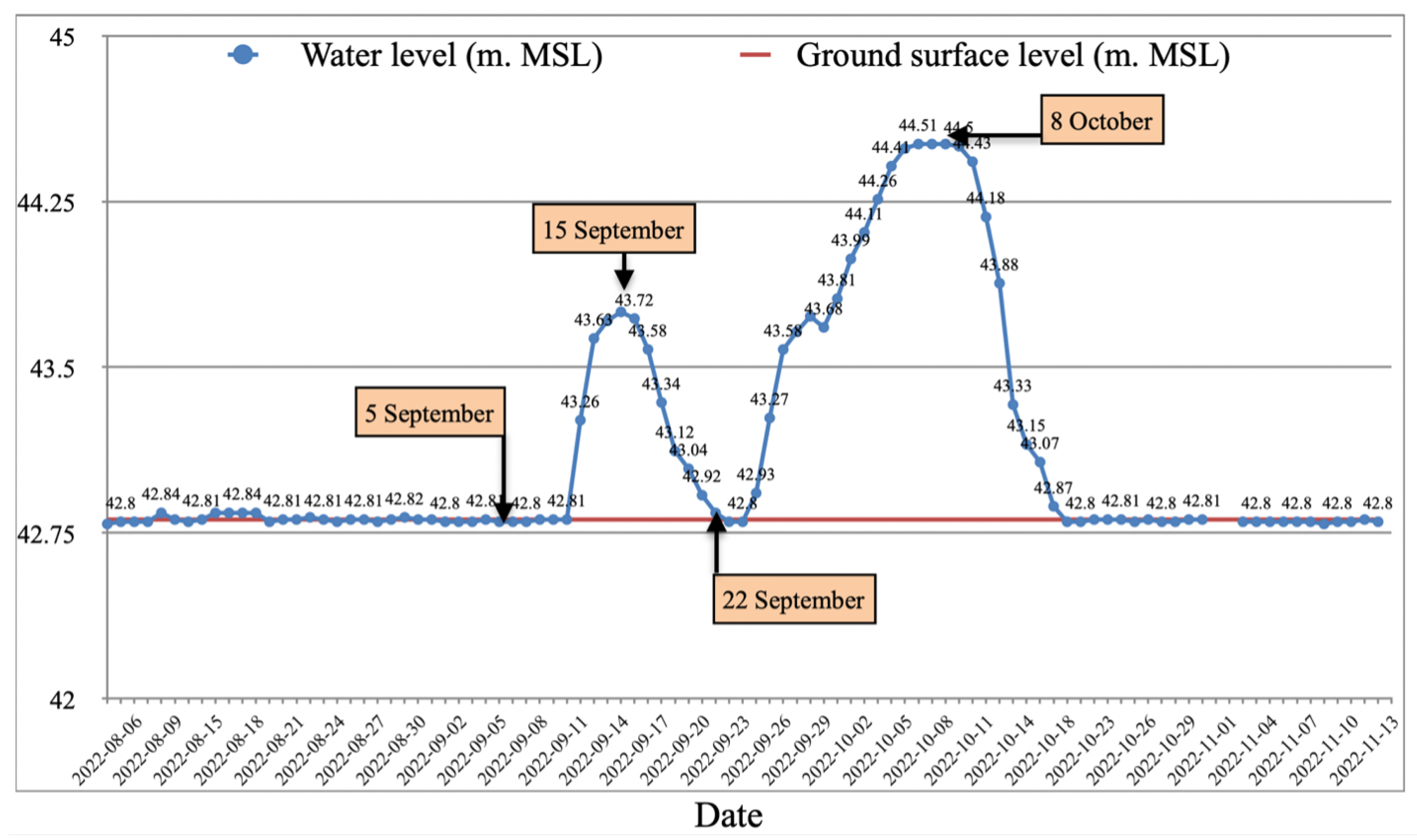

A graph of water level readings taken at Station 5 is shown in

Figure 8, which illustrates how the water level (measured in m.MSL) has changed over time. The red line indicates the station’s ground surface level, and the blue line shows variations in the water level. According to the graph, water levels first stayed constant before beginning to rise in mid-September and peaking at about 44.51 m.MSL in early October before progressively dropping back to normal levels in mid-November. With separate input and outflow times, the observed pattern accurately depicts the seasonal flood dynamics in the study area.

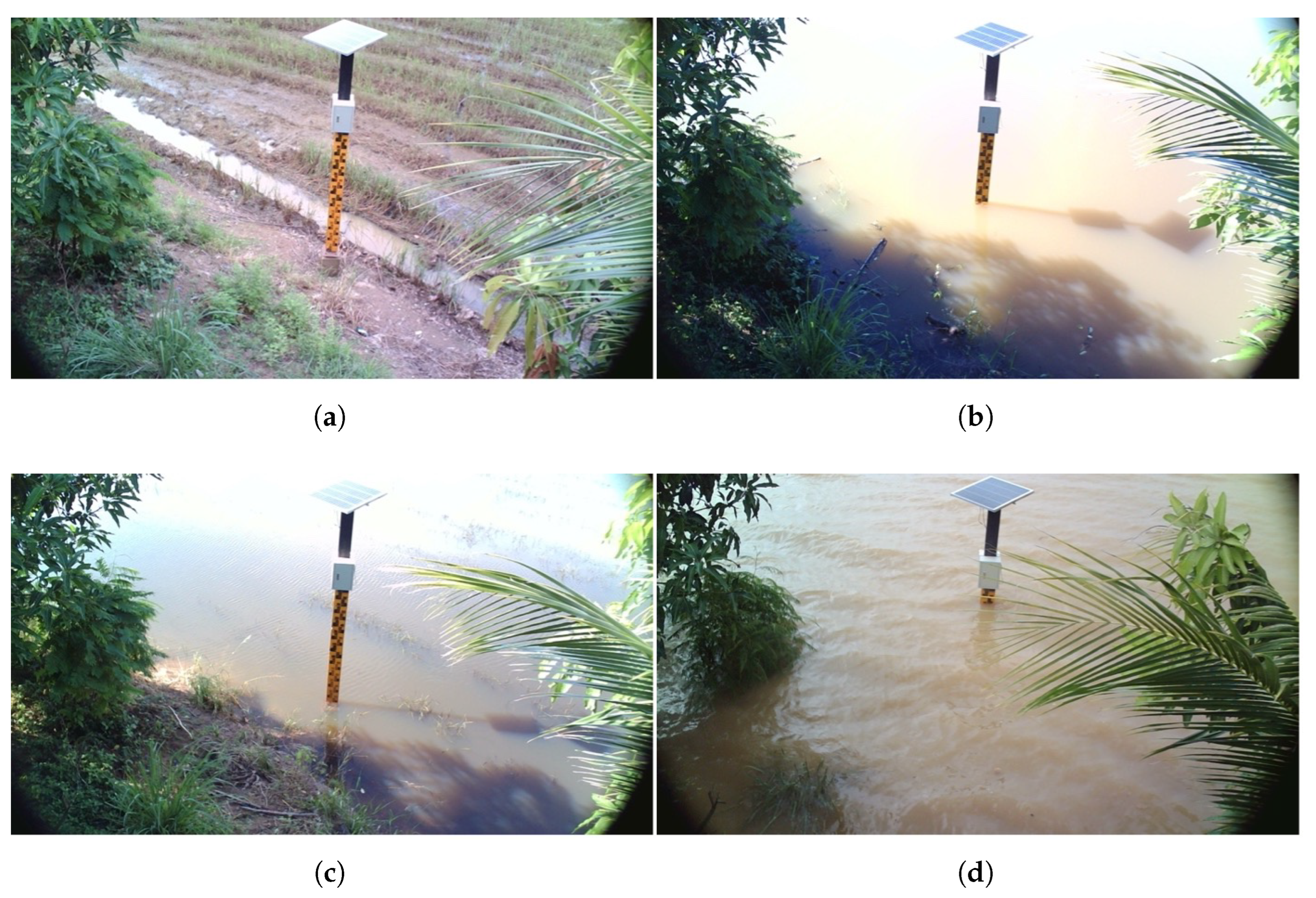

A visual record of the flooding advancement on September 5, September 15, September 22, and October 8 is shown in

Figure 9, which is taken from the monitoring camera at Station 5. The sensor is positioned in a rice field in the first photograph (September 5), which depicts a dry environment. Water gradually submerges the staff gauge as the flooding worsens, and on October 8, the water level is significantly higher, matching the peak levels shown in

Figure 9. The automatic water level monitoring system’s dependability is shown by these pictures, which visibly validate the sensor data. These images together show how the sensor-based monitoring system efficiently records flood dynamics, offering both visual and numerical confirmation—both of which are essential for flood control and decision-making in the Bang Rakam model region.

Following collection, the water level data is incorporated into the flood model for additional examination. The model simulates flood extent, depth variations, and drainage patterns throughout the research region using the reported water levels. The flood model offers a thorough depiction of water movement by integrating temporal and spatial data, enabling a more precise evaluation of flood-prone areas. In the Bang Rakam model area, this data is crucial for early warning systems, disaster management, and enhancing water management plans.

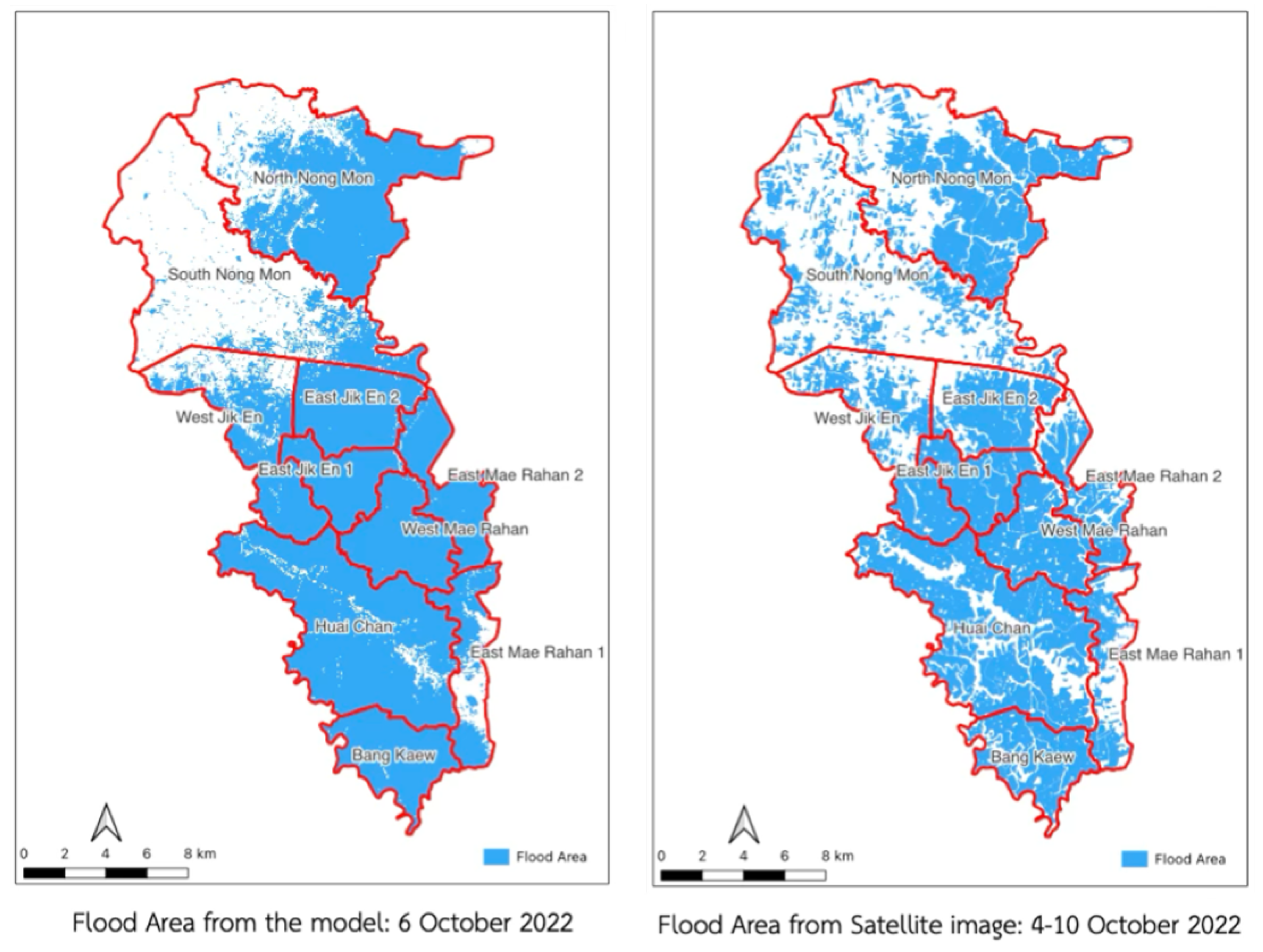

3.1. Flood from the Model Compares to Flood from Satellite Images

The comparison of flood maps produced by satellite imagery analysis and simulations reveals both parallels and discrepancies in the forecast of flood extent. We produced a simulated flood map for October 6, 2022, for this study and contrasted it with flood maps created from satellite imagery taken between October 4 and October 10, 2022. The overall flood boundary trends from both sources were aligned, as seen in

Figure 10.

In comparison to satellite data observations as shown in

Figure 11, the flood simulation model anticipated much bigger flooded areas in specific places. In some cases, the model predicted floods when none existed, while in others, it failed to detect flooding that was captured on satellite images. This reveals disparities between simulated and actual flood occurrences, indicating possible areas for improvement in model accuracy and calibration.

These disparities highlight potential deficiencies in simulation models or variations in the techniques used to collect data for satellite and ground-based observations. This simulation model solely employed ground-level data from sensor locations, which may not have represented the catchment area’s lowest points. This technique might ignore key topographic variables, resulting in mistakes in estimating water flow and flood extent during real-world flood occurrences. Satellite observations, on the other hand, give near real-time data but are susceptible to atmospheric conditions, sensor limits, and picture resolution constraints, which can result in mistakes in outlining flood borders. Furthermore, delays in satellite overpasses or cloud cover during data collection might result in incomplete or inaccurate flood area estimations.

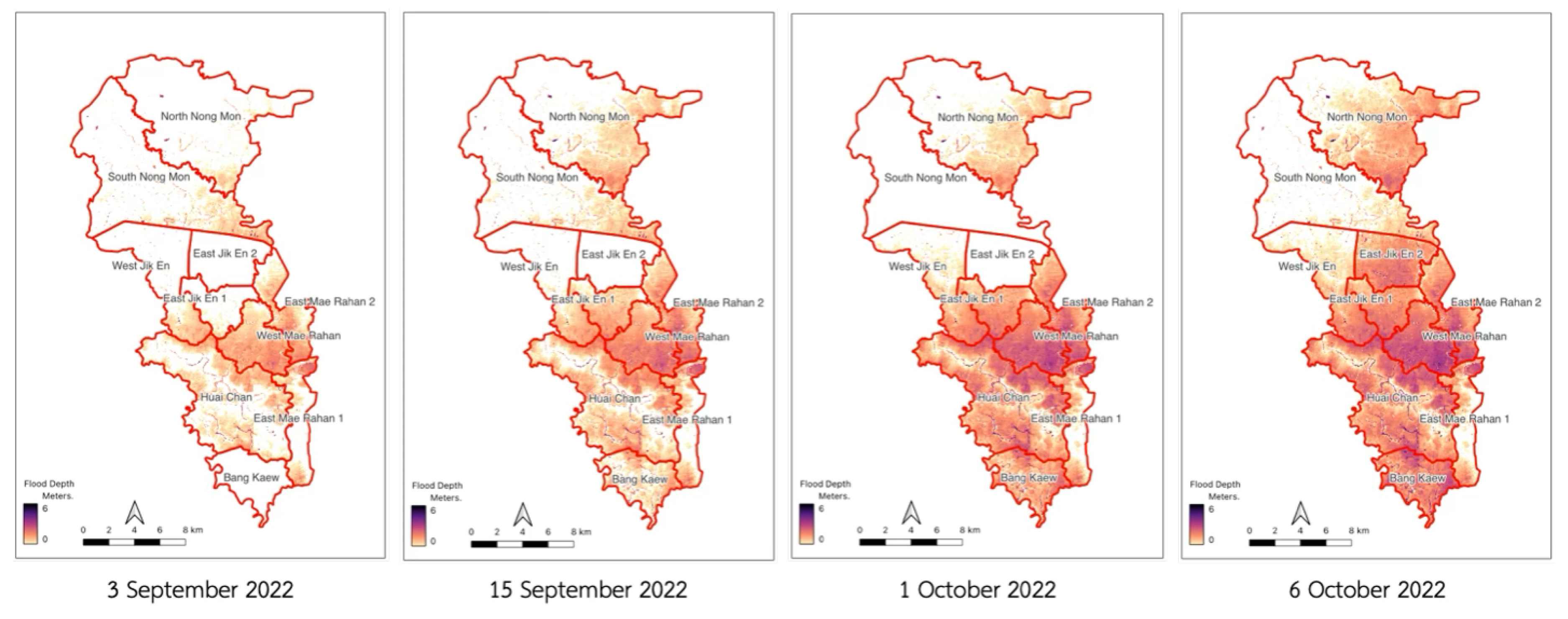

3.2. Simulate Flood Map

This paper estimated water depth levels in near real time and created flood maps using a flood analysis algorithm, as mentioned earlier. Complete data from all 10 stations was only accessible until October 6, 2022, due to damage at Station 7 and equipment collection from Stations 4 and 6 on October 7, 2022. In order to represent the scope and evolution of floods, flood simulations were run on September 3, September 15, October 1, and October 6, 2022.

According to the data, flood coverage increased gradually until it peaked in early October, when water depths in certain locations reached 6 meters. The most affected areas of the project region were in the center and south, which included the Bang Kaew, Huai Chan, West Jik En, and the western and eastern Mae Rahan fields.

The size of flood areas grew dramatically throughout the course of the investigation. According to the simulation, South Nong Mon was unaffected by the flooding, while the Huai Chan field had a massive area by October 6, 2022.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The developed system has both advantages and limitations when compared to existing systems and commercially available off-the-shelf solutions. These comparisons include aspects such as system development, installation, and, most importantly, data accuracy. The developed system achieves comparable accuracy to high-cost sensors used by the RID, offering a cost-effective alternative for flood monitoring. Furthermore, this research evaluates key factors such as cost-effectiveness, maintenance requirements, and durability, providing a comprehensive assessment of the system’s feasibility and practical implementation.

4.1. Low-Cost Water Level Sensor

The ultrasonic sensor has a measurement range of approximately 400 cm. Although this range is not exceptionally high, it is well-suited for areas with moderate flooding, such as the low-lying Bang Rakam model area. While expensive sensors can be installed at greater heights, their high costs make widespread deployment impractical. For instance, in this project, installing traditional sensors priced at 150,000 THB each across 10 stations would require a budget of 150,000 THB, which may not justify the investment in high-cost equipment for this area. Moreover, the water management operations for the Bang Rakam model area are conducted over a period of only 3–4 months per year. Investing in high-cost sensors for such a limited duration may not be economically viable. In contrast, the use of low-cost sensors developed in this study facilitates broader and more cost-effective deployment, enhancing the coverage and effectiveness of flood monitoring in the region. The developed water level sensor utilizes the Waterproof Ultrasonic Module (JSN-SR04T), which operates on low power consumption, making it suitable for battery-powered applications. Field tests conducted in flood-prone areas, along with controlled experiments using a water level simulation in a glass tank, demonstrated that the sensor provides accurate water level measurements. When compared with manual readings from a staff gauge, the sensor exhibited reliable performance. Given its high accuracy and low cost, this sensor proves to be a cost-effective solution for future water level monitoring applications.

The developed water level sensor operates on low power, making it ideal for battery-powered applications. It provides ±1 cm accuracy with millimeter-level resolution, ensuring precise water level readings. These irregularities may be attributed to various factors, including sensor errors at certain times and the detection of objects other than the water surface, such as vegetation. A 12-month field test of the sensor enclosure showed that in the early stages, before flooding occurred, the sensor occasionally misread distances due to interference from grass or weeds. However, once the study area was inundated, the system exhibited high stability, accuracy, and durability, with only minor errors. These minor discrepancies are expected in highly sensitive distance sensors, which may register false readings when objects pass through or obscure the actual water level. The implementation of water level sensors enables continuous hourly data collection, allowing users to review historical records and visualize trends through graph-based analysis, significantly improving efficiency compared to traditional manual staff gauge readings that require personnel to conduct daily measurements, typically providing a maximum of two readings per day; however, a 12-month field deployment (covering both pre-flood and actual flood periods) demonstrated that while the sensors operated effectively under real-world conditions, exhibiting durability and long-term reliability, occasional failures in data transmission to the central server were observed due to two primary factors: (1) power supply limitations, as the sensors rely on solar energy, which on cloudy or rainy days sometimes failed to store sufficient energy, leading to temporary sensor inactivity, with the recommended solution being to increase battery capacity for multiple days of operation without sunlight; and (2) internet connectivity issues, as the IoT-based sensors depend on 4G or 5G networks for data transmission, and network disruptions occasionally prevented data from reaching the central server, a problem exacerbated when combined with power shortages, with a potential solution being a network signal assessment at the installation site to determine the need for switching network providers, ultimately highlighting that despite these challenges, the developed system has proven to be an effective and scalable solution for flood monitoring, significantly improving data availability while reducing the need for manual labor, with further enhancements to power and connectivity expected to improve its reliability and operational efficiency.

4.2. Flood Model

This research employs an automated program that retrieves real-time water level data from a database to generate hourly flood maps, aligning with the sensor’s data collection intervals. The resulting maps visualize flood extent and water depth, which are then displayed on web and mobile applications for monitoring and decision-making. Additionally, all generated maps are stored on a central server, ensuring convenient access for future reference and verification. To evaluate the accuracy of the flood model developed in this study, satellite-derived flood extent data from the Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (GISTDA) were used for comparison. The analysis revealed key differences between the two datasets, which can be attributed to the following factors:

Temporal limitations of satellite data. Satellite-derived flood data rely on satellite overpasses, which occur approximately every 7 days to ensure full coverage of Thailand. As a result, there are gaps in data availability for certain periods, leading to missing or outdated information. Furthermore, the mosaicking process, which combines images from different times, may not reflect real-time flood conditions, especially if water levels have changed due to drainage or natural fluctuations within the 7-day interval[

8,

9].

Atmospheric errors in satellite image processing. Satellite-based flood mapping is dependent on image processing algorithms that apply predefined classification rules. However, atmospheric variations (e.g., cloud cover, haze, and lighting conditions) introduce errors in flood extent detection, as images captured on different days may yield inconsistent results in flood area estimation.

Exclusion of permanent water bodies. The publicly available satellite-derived flood maps typically exclude permanent water bodies such as rivers, canals, and reservoirs, as these are not considered part of the temporary flood extent. When comparing these datasets with the flood model developed in this study, this exclusion contributes to the observed differences in flood extent.

Lack of water depth information in satellite data. One major limitation of satellite-derived flood maps is the inability to provide water depth measurements. Unlike the sensor-based approach in this research, which generates flood depth maps, satellite data only indicate the presence or absence of floodwaters. The flood depth information obtained from sensors enables the calculation of floodwater volume, which is crucial for effective water management and disaster response.

Beyond its effectiveness in Bang Rakam, the developed flood monitoring system offers a scalable and cost-efficient solution for other flood-prone agricultural regions. Future work could focus on improving network connectivity for real-time data transmission and integrating machine learning algorithms to enhance flood forecasting precision.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.,K.P.,U.S.,N.K., and T.N.; methodology, S.C.,K.P.,N.K. and U.S.; software, S.C.,K.P.,R.H., and R.C.; validation, S.C.,K.P., and V.R.; formal analysis, S.C., and K.P.; investigation, V.R., and T.N.; resources, S.C., and K.P.; data curation, R.H.; writing—original draft preparation,S.C.,K.P., and R.H.; writing—review and editing, V.R.; visualization, S.C.,K.P.,R.C. and T.N.; supervision, V.R.; project administration, K.P.; funding acquisition, K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Agricultural Research Development Agency grant (Public Organization), Thailand (Grant number CRP6405032340) and was also partly supported by the Global Strategy Fund of Osaka Metropolitan University, Japan.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Agricultural Research Development Agency (Public Organization) and Osaka Metropolitan University, Japan, for their valuable support and contribution to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GIS |

Geographic Information System |

| DEM |

Digital Elevation Model |

| RID |

The Royal Irrigation Department |

| GIC |

Graphic Information Camera |

| CCTV |

Closed-Circuit Television |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| MQTT |

Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| MSL |

Mean Sea Level |

References

- Noidee, M.; Kessornpatoom, Y.; ThongKuod, W.; Bodeerat, C. Bang Rakam Model: A model for living life under flood problems. *Journal of Modern Learning Development 2024, 9*(6), 385–392. Available online: https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jomld/article/view/268434.

- Giordan, D.; Notti, D.; Villa, A.; Zucca, F.; Calò, F.; Pepe, A.; Dutto, F.; Pari, P.; Baldo, M.; Allasia, P. Low cost, multiscale and multi-sensor application for flooded area mapping. *Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2018, 18*, 1493–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, P.D.; De Roo, A.P.J. A simple raster-based model for flood inundation simulation. *Journal of Hydrology 2000, 236*(1–2), 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Fang, J.; Fang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Wu, C.; Liu, M. The Importance of Digital Elevation Model Selection in Flood Simulation and a Proposed Method to Reduce DEM Errors: A Case Study in Shanghai. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 2021, 12, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, L.; Bates, P.; Neal, J.; Rougier, J. Perspectives on Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Simulation for Flood Modeling in the Absence of a High-Accuracy Open Access Global DEM. Front. Earth Sci 2018, 6, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakuldit, T.; Faysse, N. Difficult encounters around “monkey cheeks”: Farmers’ interests and the design of flood retention areas in Thailand. Journal of Flood Risk Management 2019, 12(S2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehiakpor, D.S.; Danso-Abbeam, G.; Mubashiru, Y. Adoption of interrelated sustainable agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2021, 101(2021), 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notti, D.; Giordan, D.; Caló, F.; Pepe, A.; Zucca, F.; Galve, J. P. Potential and Limitations of Open Satellite Data for Flood Mapping. remote sensing 2018, 10(11), 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahsaini, M.; Albano, F.; Albano, R.; Mazzariello, A.; Lacava, T. A Synthetic Aperture Radar-Based Robust Satellite Technique (RST) for Timely Mapping of Floods. Remote Sensing 2024, 16(12), 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H.; Kim, M. G.; Yoon, P. R.; Bang, J. H.; Myoung, W. H.; Choi, J. Y.; Choi, G. H. Application of CCTV image and semantic segmentation model for water level estimation of irrigation channel. Journal of The Korean Society of Agricultural Engineers 2022, 64(3), 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Lee, S. H.; Choi, G. H.; Yoo, S. H.; Na, R.; Kim, H.; Yoon, K. S. Development of Methodology for Measuring Water Level in Agricultural Water Reservoir through Deep Learning anlaysis of CCTV Images. Journal of the Korean Society of Agricultural Engineers 2023, 65(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. H.; Lee, S. Deep Learning to Recognize Water Level for Agriculture Reservoir Using CCTV Imagery. Water Resources Management 2024, 38(3), 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, H.R.; Ghashala, K.K.; Sharma, S. Post flood management system based on smart IoT devices using AI approach. meterialstoday proceedings 2021, 46(20), 10411–10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, A. I.; Kulkarni, M. A. P.; Gaikwad, M. N. L.; Powar, M. P. M.; Surve, A. R. An IoT and AI based flood monitoring and rescue system. Int. J. Eng. Tech. Res 2020, 9(9), 564–567. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Ahmad, M.; Jeon, G.; Chehri, A. An internet of things and ai-powered framework for long-term flood risk evaluation. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 11(3), 3812–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Barthwal, A.; Acharya, D. FLOODWALL: a real-time flash flood monitoring and forecasting system using IoT. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 23(1), 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, S.; Kang, J.; Lee, I. A study on real-time flood monitoring system based on sensors using flood damage insurance map. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2018, 42, 569–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Barthwal, A.; Acharya, D. An IoT-based system for monitoring and forecasting flash floods in real-time. Journal of Earth System Science 2023, 132(4), 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strigaro, D.; Capelli, C.; Cannata, M. An open early-warning system prototype for managing and studying algal blooms in Lake Lugano. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2024, XLVIII-4/W12-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznichenko, S.; Buchynska, I.; Kovalenko, L.; Tereshchenko, T. Integrated information system for regional flood monitoring using internet of things. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings 2019, 2683, 1–5. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2683/paper1.pdf.

- Zeng, F.; Pang, C.; Tang, H. Sensors on the Internet of Things Systems for Urban Disaster Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2023, 23(17), 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, R. M. P. N. S.; Jayasignhe, A. B.; Retscher, G. The Integration of IoT (Internet of Things) Sensors and Location-Based Services for Water Quality Monitoring: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2025, 25(6), 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. H.; Lee, S. Deep Learning to Recognize Water Level for Agriculture Reservoir Using CCTV Imagery. Water Resources Management 2024, 38(3), 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diriyana, A.; Darusalam, U.; Natasha, N. D. Water Level Monitoring and Flood Early Warning Using Microcontroller With IoT Based Ultrasonic Sensor. Jurnal Teknik Informatika CIT Medicom 2019, 11(1), 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odli, Z. S. M.; Izhar, T. N. T.; Razak, A. R. A.; Yusuf, S. Y.; Zakarya, I. A.; Saad, F. N. M.; Nor, M. Z. M. Development of portable water level sensor for flood management system. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2016, 11(8), 5352–5357. [Google Scholar]

- Tejaswitha, V.; Babu, M. J. Monitoring of water level variations in rivers and flood alert system using wireless sensor networks. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology 2016, 3(07). Available online: https://www.irjet.net/archives/V3/i7/IRJET-V3I786.pdf.

- Choosumrong, S.; Hataitara, R.; Panumonwatee, G; Raghavan, V.; Nualsri, C.; Phasainam, T.; Phasinam, K. Development of IoT based smart monitor and control system using MQTT protocol and Node-RED for parabolic greenhouse solar drying. Int. j. inf. tecnol. 2023, 15, 2089–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyowati, R.; Sujono, H.A.; Musthofa, A.K. A River Water Level Monitoring System Using Android-Based Wireless Sensor Networks for a Flood Early Warning System. In Proceedings of Second International Conference on Electrical Systems, Technology and Information 2015 (ICESTI 2015); Pasila, F., Tanoto, Y., Lim, R., Santoso, M., Pah, N., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2016; vol 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividad, J. G.; Mendez, J. M. Flood monitoring and early warning system using ultrasonic sensor. In IOP conference series: materials science and engineering325(1); 2018; p. 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phasinam, T.; Phasinam, K.; U-kaew, A.; Piyathamrongchai, K.; Hataitara, R.; Raghavan, V.; Nemoto, T.; Choosumrong, S. Real-Time Monitoring and Positioning of Agricultural Tractors Using a Low-Cost GPS and IoT Device. International Journal of Geoinformatics 2024, 21(1), 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hataitara, R.; Piyathamrongchai, K.; Choosumrong, S. Development of an emergency notification system to analyze the access route for emergency medical services using Geo-IoT and pgRouting. Appl Geomat 2024, 16, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, M.K. Efficiency of JSON for Data Retrieval in Big Data. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2017, 7(1), 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Park, E.Y. Search performance evaluation of JSON datasets in a big data environment. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2022, 7(1), 198–203. Available online: https://kalaharijournals.com/resources/IJME-21-40/IJME_Vol7.1_27.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).