1. Introduction

The incidence of femoral periprosthetic fractures is expected to increase due to increasing life expectancy in most countries and increasing provision of hip and knee arthroplasty worldwide. Across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, over 3.4 million hip and knee arthroplasty surgeries have been in the national joint registry since 2003. Femoral periprosthetic fractures contribute to 2.5 % of indications for revision arthroplasty surgery with their frequency ranging from 1.5% in primary implants and about 7% in revision arthroplasty [

5,

6]. A retrospective data review over a 15-year period in a single center found periprosthetic fractures occurred in 1.2% of patients treated with cephallomedullary nailing and had post operative hospital mortality rate of almost 17% within 90 days [

7]. The treatment of periprosthetic fractures, however, remains very challenging and requires specialist expertise and equipment. Management of these injuries is guided by both patient and injury factors. Generally, treatment options of periprosthetic fractures of the femur may be non-operative or operative, which may be open reduction and internal fixation, or revision arthroplasty. Although surgical intervention can be a complex undertaking, non-operative management carries increased risk of malunion and non-union. This potentially may lead to prolonged periods of immobility and decline in patient’s function and independence [

8,

9]. The mortality rate with these injuries can be as high as 11% in the first year which is concerning [

10]. The aim of our study is to review outcomes of patients treated with NCB plating for femoral periprosthetic fractures over a 10-year period in our arthroplasty unit

2. Classification

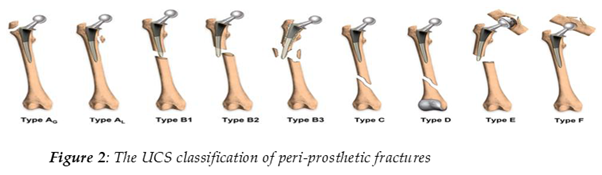

In periprosthetic fracturs involving Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA), the Vancouver classification by Duncan and Masri (1995) remains popular and provides a good guide to management, similar to Su and Associates' Classification of Supracondylar Fractures of the Distal Femurs around total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [

11]. In our study, however, we adopted the UCS classification Table 1 of [

12] to streamline a comprehensive description of periprosthetic fractures in our case series which included both knee and hip arthroplasty, originally published in the 2014 Bone and Joint Journal by Duncan and Haddad.

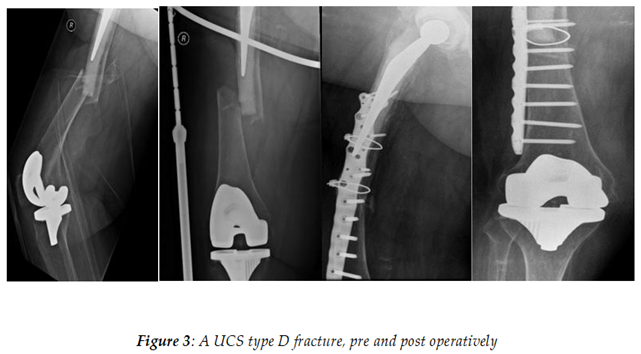

In a well-fixed stem, treatment with an open reduction and internal fixation remains an option for patients, with multiple techniques and devices having been developed over the years. For the purposes of reduction and synthesis; A, B1, C and D type fractures would be proposed to be most amenable due to the presence of a stable implant. Our choice of implant was the Zimmer Non-Contact Bridging Plate (NCB) which provides a polyaxially angular stability combined with conventional plating [

13]

3. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed notes and radiographs of patients who presented with femoral periprosthetic fractures to our unit from January 2012 to December 2022. An inclusion criterion was set for all patients treated with NCB plating with retention of implant. There were no exclusion criteria for patients.

We identified 111 patients over this period using our hospital’s electronic theatre management systems. All patients had appropriate radiographs of injuries pre operatively , intra operatively and at follow up when arranged.

Each patient’s clinical notes were reviewed to identify relevant patient demography, functional status and mobility pre and post operatively, as well as duration of hospital stay. Operative notes were reviewed identifying grade of operating surgeon, choice of implant, use of augments, plate length and weight bearing instructions post operatively. All patient radiographs were reviewed to assess for preoperative UCS classification, comminution, implant type and working length, and post operative radiological union.

Patients had a wound check appointment at 2 weeks followed by a clinic review at 3 months and discharged at union or 1 year follow up.

The main outcomes measured were length of admission, post operative mobility and function at final follow up or 1 year follow up , union , implant failure , soft tissue complications, reoperation rates including revision and mortality (30 days and 1 year).

Non-union was defined as no evidence of callus formation on radiographs after 3 months follow up as documented in clinic letters.

4. Results

Epidemiology of study: In our 111 patient cohort, median age was 81 with 72 patients ASA 3 or above. Hospital stay ranged from 4 to 143 days (Median=20 days). 24% of cases were males, whilst 76% of cases were females. There was a consultant scrubbed in all cases with most lead surgeons being Consultant grade (n=109).

The periprosthetic fractures involved 68 total hip replacements, 1 hip hemiarthroplasty, 17 intramedullary nails and 42 total knee replacements. As per the UCS classification of fractures we recorded A (n=1), B1 (n=49), B2 (n=10), C (n=34) and D (n=14). All surgeries were done open with the most frequent plate length being the 9-hole plate (41.4%) augmented with further screws or screws with cables for all patients.

| Complication. |

Non-Union |

Implant Failure |

Joint revision |

Wound Dehiscence |

| Incidence |

12 (10..8%) |

6 (5.4%) |

7 (6.31%) |

1 (0.09%) |

Complications: 12 fractures post-fixation went into non-union with 6 concurrent implant failures in this group. Average working length of plates in patients with non-union was 170mm. Of those 12 patients identified to have non-union, 42% were classification B1 (n=5), 33% (n=4) were C and 25% were D (n=3). One patient with non-union and plate fracture declined further intervention with all others in the group having a repeat procedure. One patient had wound dehiscence requiring debridement and closure. At time of final follow up, there was a revision arthroplasty rate of 6.31% (n=7) for infection, re-fracture and aseptic loosening.

Mobility outcomes: Post operatively, most patients (56.7%) were non-weight bearing (NWB), with 12 patients (10.8%) allowed to fully weight bear (FWB). 82 patients lived in their own homes at time of injury, and 13.4% (n=11) of these patients were discharged requiring more support at their discharge destination. Most patients (n=75) maintained their prehospital mobility or better at final follow up. Of those who were independent pre-operatively, 43% maintained their pre-hospital mobility. Of those who used walking aids, 64% maintained or improved their pre-hospital mobility. Of those who used zimmerframes, 82% maintained or improved their pre-hospital mobility.

| 30 day mortality |

1 year mortality |

| 4.01 % |

14.4% |

| Mobility Prior to Admission |

Number of Patients who maintained or improved prehospital mobility |

| Independent |

43% |

| Sticks/Aids |

64% |

| Zimmer-frame |

82% |

Mortality: Mortality at 30 days and 1 year post-operatively was 4.01% and 14.4% respectively. There was one inpatient death. This was in keeping with averages in current literature, when comparing with other similar studies [

17].

5. Discussion

The UCS classification system was more useful when gathering our data compared to the Vancouver classification system. Being able to categorize all types of periprosthetic fractures compared to solely fractures surrounding prosthetic hip joints allowed for a greater sample size to be evaluated, with 42 knee replacements in our study that would otherwise not have been included.

The incidence of periprosthetic fractures is highest among frail patients with multiple comorbidities [

14,

15,

16]. In our study, this was evident with a high median age and most patients with ASA grades above 2. The concern with these patients is the complications of immobilization thus our aim of treatment was to allow early mobilization when able.

Our recorded 30-day mortality of 4.01% was less than results reported in a similar cohort treated with NCB plates (9.5%) [

17].

Although most patients were initially instructed as NWB, all patients except one were mobilized post operatively. As expected, mobility outcomes were shown to be higher in those patients whose pre-hospital admission mobility status was that which already used mobility aids. Given that only 42% of patients who were independently mobile pre-operatively regained their pre-hospital mobility, questions can be raised as to why this could be the case. One explanation would be to consider the general demographic of the patients, and the likely associated frailty and co-morbidity that comes with the median age of our cohort (81). The major surgery required in treating these fractures would naturally decrease a frail, co-morbid patients’ mobility.

More complications occurred in UCS type B1 fracture than any other sub-type. However, given that far more type B1 fractures were surveyed in total this could account for this increase in complication rate seen.

6. Conclusions

We believe that NCB plates remain an effective way of treating periprosthetic fractures, as evidence by maintaining mobility in 68% of patients with a 4.01% 30-day mortality rate, and 86.6% of patients who were admitted from their own home returning to their own home as a discharge destination.

Further work on the use of fracture specific plates in combination with other devices to allow early weight bearing is recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Buadooh and A.Ng; methodology, A.Korosi. and K. Buadooh; software, A.Korosi and K.Buadooh; validation, A.Ng and T. Boddice; formal analysis, A.Korosi and K.Buadooh; investigation, A.Korosi, K.Buadooh, A.Ng and T. Boddice; resources, A.Korosi, K.Buadooh, A.Ng and T. Boddice; data curation A.Korosi and K.Buadooh; writing—original draft preparation, A.Korosi and K.Buadooh; writing—review and editing, A.Ng and T. Boddice; supervision A.Ng and T. Boddice. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects (who had not passed away at time of study) involved in the study

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NCB |

Non Contact Bridging |

| UCS |

Unified Classification System |

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiology |

| TKA |

Total Knee Arthroplasty |

| THA |

Total Hip Arthroplasty |

| NWB |

Non weight bearing |

| FWB |

Fully Weight Bearing |

References

- De Meo D, Zucchi B, Castagna V, Pieracci EM, Mangone M, Calistri A, et al. Validity and reliability of the Unifed Classifcation System applied to periprosthetic femur fractures: a comparison with the Vancouver system. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(8):1375–81.

- Haddad FS, Duncan CP, Berry DJ, Lewallen DG, Gross AE, Chandler HP. Periprosthetic femoral fractures around well-fxed implants: use of cortical onlay allografts with or without a plate. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(6):945–50.

- Pike J, Davidson D, Garbuz D, Duncan CP, O’Brien PJ, Masri BA. Principles of treatment for periprosthetic femoral shaft fractures around well-fxed total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(11):677–88.

- National Joint Registry 20th Annual Report 2023. https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/national-joint-registry-20th-annual-report-2023/, Accessed on 9/5/24 at 15:49.

- Duwelius PJ, Schmidt AH, Kyle RF, Talbott V, Ellis TJ, Butler JBV. A prospective, modernized treatment protocol for periprosthetic femur fractures. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2004;35:485–492.

- Tsaridis E, Haddad FS, Gie GA. The management of periprosthetic femoral fractures around hip replacement. Injury. 2003;34:95–105.

- Lang NW, Joestl J, Payr S, Platzer P, Sarahrudi K. Secondary femur shaft fracture following treatment with cephalomedullary nail: a retrospective single-center experience. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017 Sep;137(9):1271-1278. Epub 2017 Jul 18. PMID: 28721591. [CrossRef]

- Mcelfresh EC , MB Coventry Femoral and pelvic fractures after total hip arthroplasty.JBJS. 1974; 56: 483-492.

- Duncan CP, Masri BA. Fractures of the femur after hip replacement.Instr Course Lect. 1995; 44: 293-304.

- Bhattacharyya T, Chang D, Meigs JB, Estok DM, Malchau H. Mortality after periprosthetic fracture of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2007;89(12):2658–62.

- Su ET, DeWal H, Di Cesare PE. Periprosthetic femoral fractures above total knee replacements. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12(1):12–20. [CrossRef]

- Duncan CP, Haddad FS. The Unifed Classifcation System (UCS):improving our understanding of periprosthetic fractures. Bone Joint J.2014;96-B(6):713–6.

- Erhardt JB, Grob K, Roderer G, Hoffmann A, Forster TN, Kuster MS. Treatment of periprosthetic femur fractures with the non-contact bridging plate: a new angular stable implant. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008 Apr;128(4):409-16. Epub 2007 Jul 18. PMID: 17639435. [CrossRef]

- Farrow L., Ablett A.D., Sargeant H.W., Smith T.O., Johnston A.T. Does early surgery improve outcomes for periprosthetic fractures of the hip and knee? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021;141:1393–1400. [CrossRef]

- Boddapati V., Grosso M.J., Sarpong N., Geller J.A., Cooper H.J., Shah R.P. Early Morbidity but Not Mortality Increases with Surgery Delayed Greater Than 24 Hours in Patients with a Periprosthetic Fracture of the Hip. J. Arthroplast. 2019;34:2789–2792. [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Lynn S., Ngu A., Holland J., Carluke I., Fearon P. The effect of delay to surgery on morbidity, mortality and length of stay following periprosthetic fracture around the hip. Injury. 2016;47:725–727. [CrossRef]

- Rahuma MA, Noureddine H. The Outcome of Fixing Distal Femur Periprosthetic Fracture around Total Knee Replacement using a Locking Plate Non-Contact Bridging (NCB). Malays Orthop J. 2022 Mar;16(1):46-50. PMID: 35519537; PMCID: PMC9017929. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).