1. Introduction

Cacao is one of Ecuador’s most emblematic crops, internationally recognized for its “fine aroma” quality. National production exceeds 333,700 tons annually, and the activity involves hundreds of thousands of small- and large-scale farmers. For instance, Charry [1] reports that approximately 260,000 producers from Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru jointly harvested around 584,000 tons of cacao in 2020/21, reflecting the crop’s significant social and economic importance for rural communities. This productive dynamism positions the cacao sector as a pillar of the local economy and a major export commodity—vital to the livelihoods of countless farming families.

Accurately forecasting cacao yields is complex due to high climatic variability and the presence of multiple biotic and abiotic factors. Droughts, frost, or pests can cause abrupt yield fluctuations, making agricultural planning challenging. Traditional estimation methods based on partial forecasts or empirical knowledge often prove unreliable in the face of such complexity. In response to these challenges, artificial intelligence (AI) offers a promising approach: AI-based models can simulate how changes in climatic variables and crop management practices affect production, thereby suggesting adaptation strategies. According to Mohan [2], AI predictive models “can simulate how climate change will affect crops and recommend strategies to make agriculture more resilient.” In this context, AI provides the tools to analyze complex relationships between climate and crops, while NWP models offer prospective meteorological information that enables informed predictions and potentially enhances the resilience and effectiveness of the agricultural sector. Having advanced prediction tools is therefore crucial to improving decision-making in the field.

In Ecuador’s most remote regions, the lack of connectivity in the field makes it essential for mobile applications to function offline. A relevant example is the study by Pineda [3], who developed a free, offline application for diagnosing potato diseases, designed to be compatible with low-performance devices. The authors highlight that such an app, being “free, offline, and suitable for low-end devices, can serve as a decision-support assistant,” enabling real-time diagnoses without internet access. Similarly, a cacao yield prediction system based on AI can be implemented in an application that works offline, allowing farmers to consult yield estimates directly in the field where network coverage is unavailable. These mobile technologies facilitate the adoption of artificial intelligence in farming communities by bringing complex analysis tools directly to producers.

Digital technologies powered by artificial intelligence provide significant value to cacao agriculture; the digitalization of the agricultural sector has been shown to increase both efficiency and productivity. For example, Shamshiri [4] reports that digitalization enables real-time crop monitoring, which leads to higher yields and reduced input waste. Likewise, Mohan [2] emphasizes that “predictive analytics, driven by artificial intelligence and machine learning, provide farmers with actionable insights and transform reactive practices into proactive strategies.” In practice, an offline mobile application with AI-supported harvest predictions would help Ecuadorian cacao producers plan planting and fertilization activities more accurately, optimizing input use and reducing risks. In this way, such tools contribute to the sustainability and competitiveness of the cacao sector by offering farmers and other stakeholders reliable, data-driven decision-making support.

2. Methods

This study followed the CRISP-DM (Cross-Industry Standard Process for Data Mining) methodology, which consists of six stages: business understanding, data understanding, data preparation, modeling, evaluation, and deployment. This approach was selected due to its proven effectiveness in projects that involve developing predictive models and integrating them into technological tools. The methodology enabled a structured and iterative development of the cacao yield prediction system [5].

2.1. Understanding of the Agricultural Problem

This phase involved analyzing the cacao production context in the province of Cotopaxi, specifically in the canton of La Maná, where the needs of farmers regarding yield prediction, harvest planning, and input optimization were identified. This understanding made it possible to define the main objective: the development of an accessible predictive system, operable without internet connection, and capable of providing reliable estimates under limited connectivity conditions.

2.2. Data collection and Processing

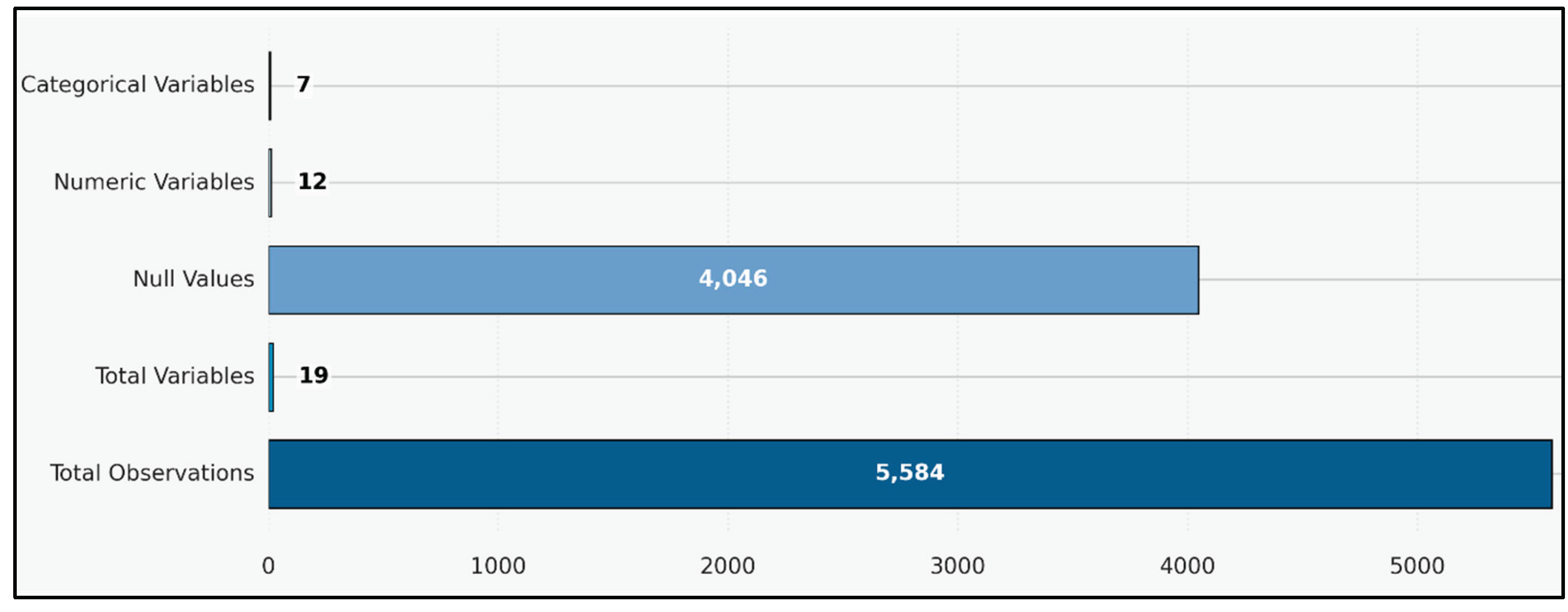

A dataset composed of 5,584 observations and 19 independent variables was collected using meteorological and soil sensors deployed in experimental plots in the canton of La Maná. The variables included temperature, relative humidity, precipitation, soil pH, electrical conductivity, plant height, stem diameter, number of branches, among others. The data correspond to three cacao genotypes: CCN-51, Cacao 800, and Cacao 801, which are widely cultivated in the region. Data cleaning involved the removal of outliers, treatment of missing values, and the application of scaling techniques such as normalization and standardization, following the best practices recommended by Fan [6],

Figure 1 presents a graphical diagram illustrating the structure of the dataset. Python was used for data transformation and preparation of the training set, utilizing libraries such as Pandas, Numpy, and Scikit-learn.

2.3. Comparison and Selection of Predictive Algorithms

With the objective of identifying the most suitable model for estimating cacao yield under variable field conditions, a comparative evaluation was conducted among five supervised learning algorithms: Decision Trees, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and XGBoost. This comparison was based on quantitative performance metrics such as the coefficient of determination (R²), root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean squared error (MSE), using the same training and testing datasets to ensure fair evaluation conditions, in accordance with the recommendations of Chicco [7].

For the models that produced distinct results for each target variable (plant height, stem diameter, and number of fruits), average values were calculated in order to obtain a representative global metric. The comparative results revealed substantial differences among the evaluated algorithms. While Gradient Boosting and Random Forest showed strong performance metrics, the XGBoost model achieved the highest performance, with a global coefficient of determination of 0.9399 and the lowest RMSE (7.32), consistently outperforming the other techniques analyzed.

These findings, summarized in

Table 1, support the selection of XGBoost as the final model for implementation in the mobile application, as it combines predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and stability in agricultural environments characterized by high variability in conditions.

2.4. Predictive Modeling with XGBoost.

To construct the predictive model, the XGBoost algorithm was employed as the primary machine learning technique. This approach was chosen for its ability to efficiently model nonlinear relationships, its robustness against overfitting, and its high performance in prediction tasks under highly variable conditions—making it particularly suitable for agricultural mobile applications [8].

The model was trained on 80% of the dataset, with 10% reserved for validation and the remaining 10% for testing. To prevent overfitting, key hyperparameters were tuned, including the learning rate, maximum tree depth, and number of iterations. Although XGBoost does not use pruning in the same way traditional decision tree models do, it incorporates early regularization mechanisms—such as gamma and min_child_weight—which control tree growth and help prevent overfitting [9].

In the practical implementation of the model, the HistGradientBoostingRegressor estimator from the Scikit-learn library was used, as it is considered an efficient alternative to XGBoost due to its optimized histogram-based structure and its ability to scale with large datasets. This model was trained individually for each target variable (plant height and stem diameter), using a low learning rate of 0.01, a moderate tree depth (max_depth = 6), and a high number of iterations (max_iter = 12,000) to achieve progressive convergence.

The metrics used to evaluate the model included Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and the Coefficient of Determination (R²), in line with recent studies on agricultural prediction such as that of Joshua [10]. The model’s satisfactory performance demonstrated its generalization capability and robustness in environments with multiple sources of variability. Recent studies confirm the effectiveness of this type of model in crops such as rice, maize, and tomato under variable climatic conditions.

2.4. Mobile Application Development

The trained model was packaged and deployed in an offline mobile application developed using the React Native framework, enabling local execution on Android devices. The model file (APK) was serialized using Joblib and loaded directly from the user’s device, eliminating the need for an internet connection.

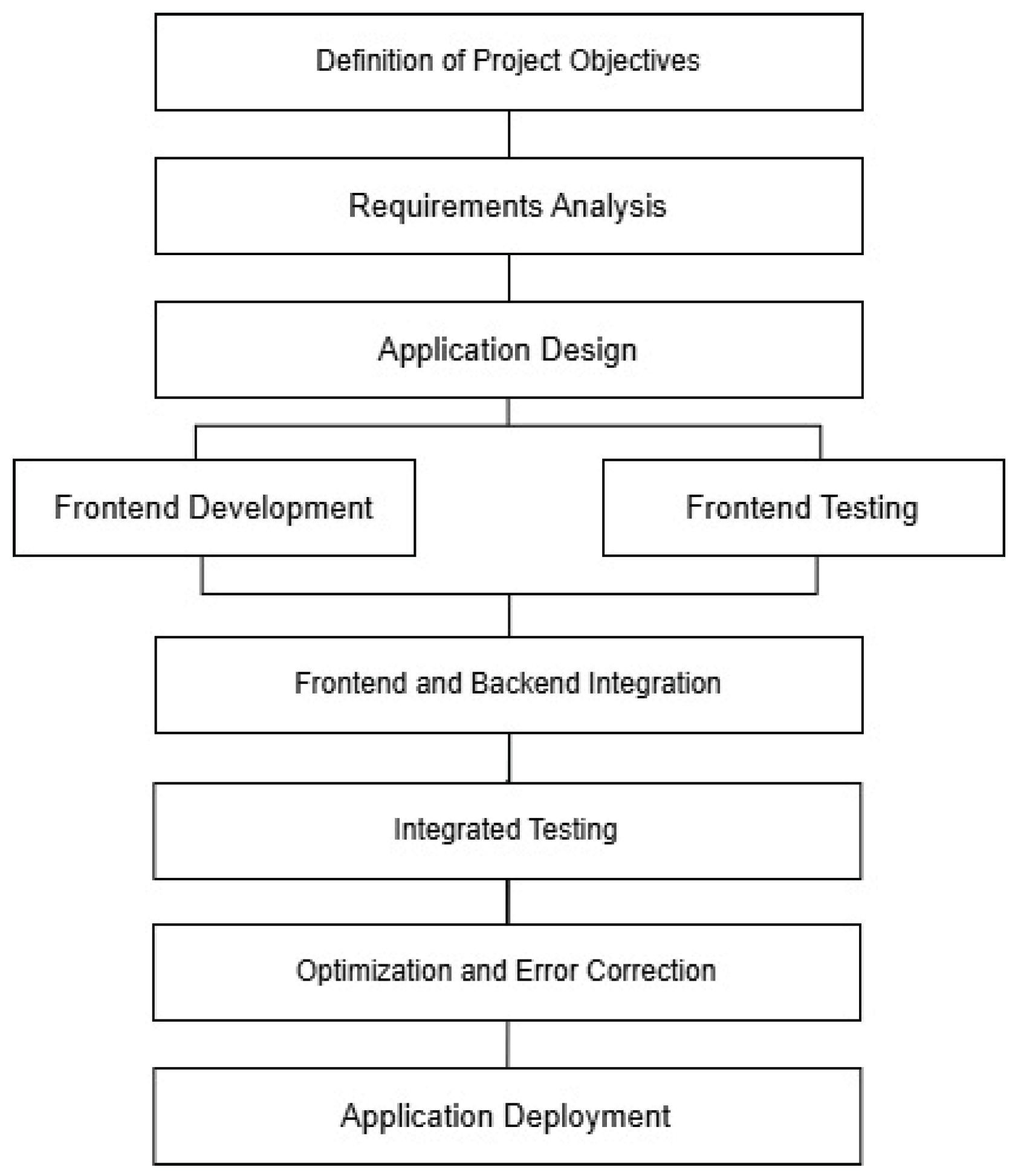

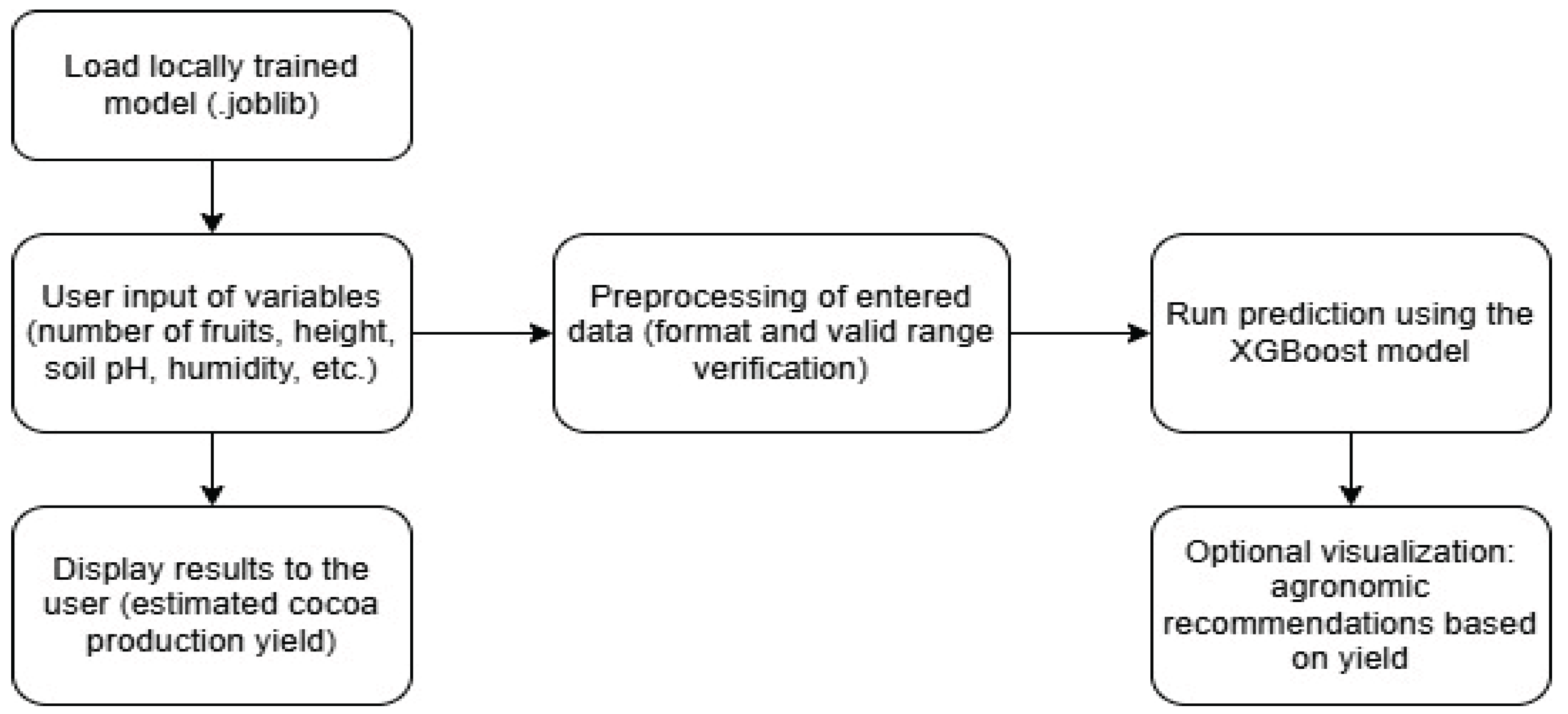

The graphical interface allows users to select the cacao genotype, input environmental and management variables, and receive as output the estimated yield prediction (in kg/ha). Input validations were implemented to control data entry and display error messages in case of inconsistencies. This strategy has proven effective in other agricultural applications deployed in remote areas, according to Pechlivani [11]. The development of the application is summarized in

Figure 2.

2.5. Implementation and Functional Validation Testing

The application was converted to APK format and deployed on Android mobile devices using the Buildozer tool. Subsequently, functional testing was conducted in rural cacao-producing communities. The tests focused on evaluating the application’s ability to operate offline, the accuracy of its predictions, response times, and the user-friendliness of the interface [12].

The system was validated using black-box testing techniques and participatory observation. Users reported a satisfactory experience, highlighting the usefulness of the predictions for planning planting activities and managing inputs. The application maintained an average response time of under 5 seconds and was compatible with low-end devices.

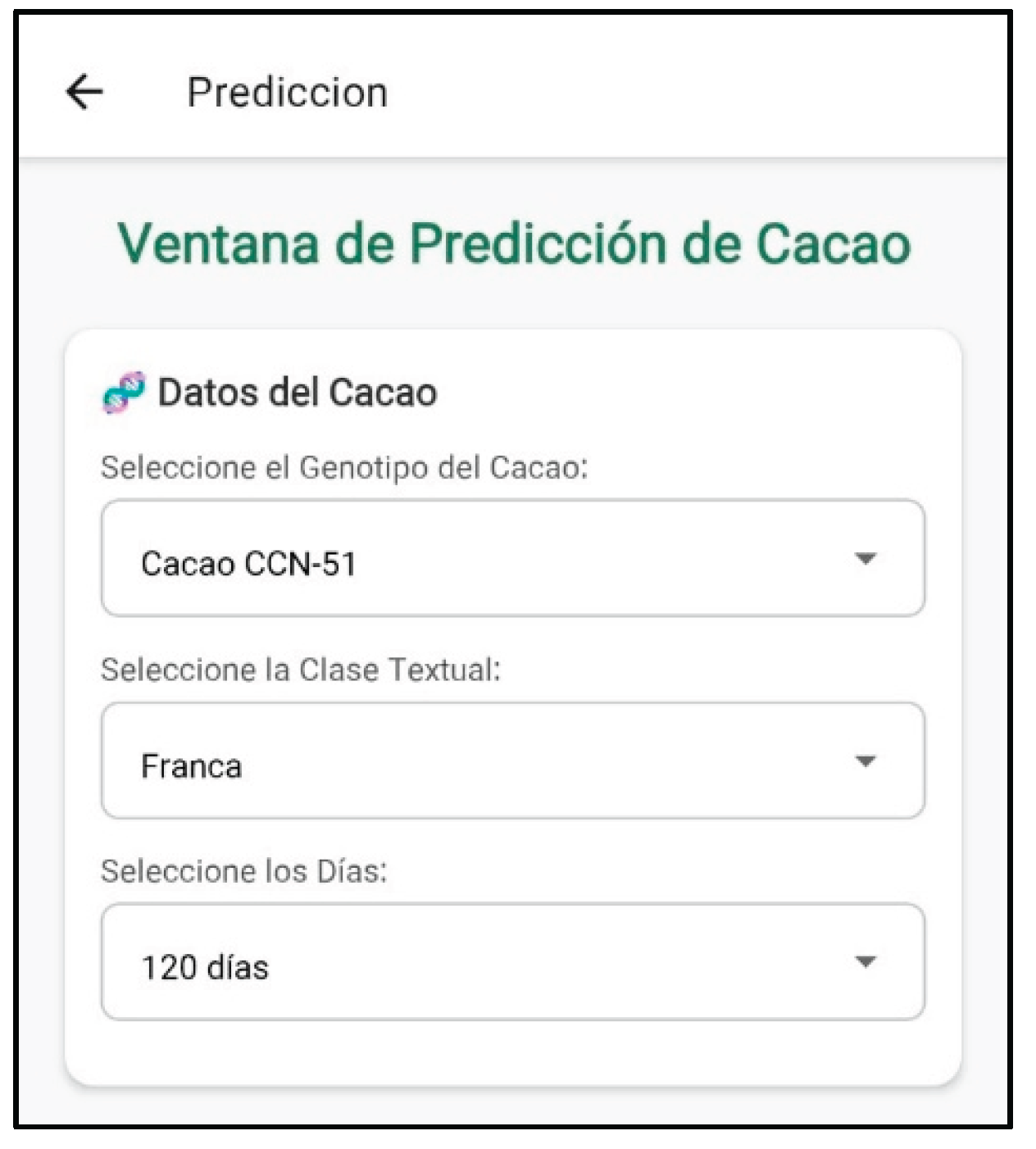

Figure 3 displays a screenshot of the application in operation.

3. Results and Discussion

The implementation of the XGBoost model and its deployment in an offline mobile application for cacao yield forecasting produced significant results in terms of accuracy, interpretability, and practical applicability. The most relevant findings of the study are presented and discussed below, grouped into five main areas: data behavior, validation of the predictive model, variable importance, technical performance of the application, and end-user perception.

3.1. Performance of the XGBoost Model

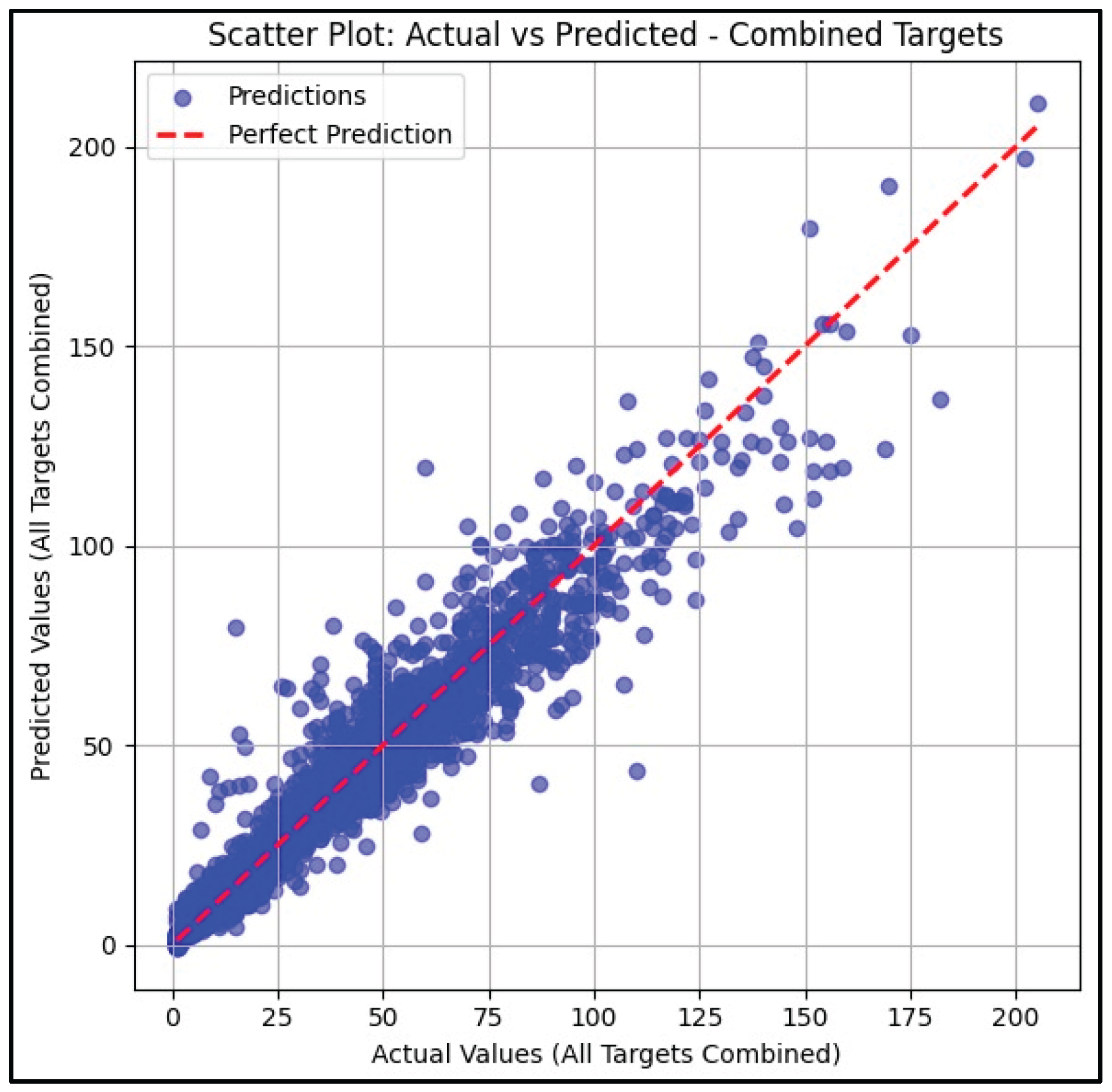

Chico [7] discusses the importance of the coefficient of determination (R²) as a key metric for evaluating the fit of predictive models. The XGBoost model was evaluated using standardized metrics such as Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and the Coefficient of Determination (R²). The results obtained during the validation and testing phases indicated a high degree of fit between the model’s predictions and the actual values observed in the experimental plots.

The values obtained for each of these metrics were as follows:

Mean Square Error Medio (MSE): 53.6068

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): 7.3217

Coefficient of Determination (R²): 0.9399

These results reflect a good model fit, demonstrating adequate predictive capability for cacao yield under the specific conditions of the experimental plots. Additionally, a close alignment with the diagonal can be observed in the scatter plot of actual versus predicted values in

Figure 4, which highlights the model’s ability to accurately estimate cacao yield. This correlation remained stable even under climatic variability, validating the supervised learning approach for this type of crop.

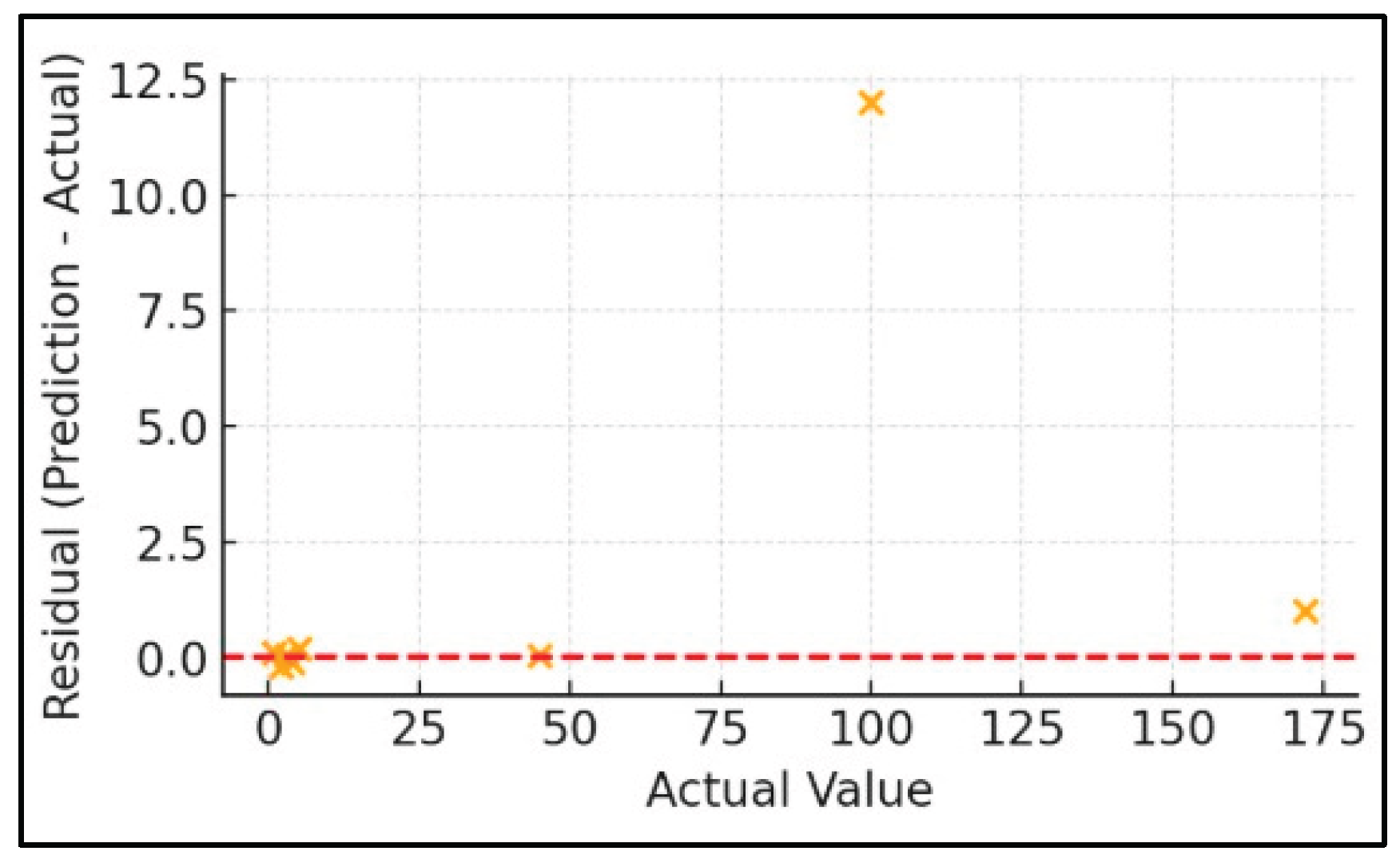

An error analysis was conducted using residual plots to identify potential biases or patterns not captured by the model. The results showed a random distribution of errors (

Figure 5), suggesting that the model does not exhibit systematic errors and is robust to variations in soil and climatic conditions.

The model’s accuracy was particularly high for genotypes such as CCN-51, which is widely cultivated in the region. This suggests that the algorithm successfully captured relevant growth and productivity patterns associated with specific edaphoclimatic conditions. This behavior is consistent with the findings of Nti [13], who reported strong performance of the XGBoost model in tropical crops.

3.2. Variable Importance Analysis

The evaluation of feature importance made it possible to identify which variables had the greatest influence on yield predictions. Among the most relevant variables were the number of fruits, plant height, soil pH, and relative humidity. These results are consistent and show a strong correlation with cacao productivity.

The number of fruits accounted for more than 25% of the variance in yield prediction, reinforcing its value as the primary predictor. This finding provides empirical evidence to guide specific agronomic practices, such as pest control and pruning, which directly influence fruit production [14].

3.3. Technical Evaluation of the Offline Mobile Application

The predictive model was successfully implemented in an offline mobile application, featuring an intuitive interface that allows users to input environmental and management variables and obtain yield predictions. Functional testing showed that the app maintains a response time of under five seconds, even on low-end devices an essential factor for its adoption in rural environments with limited technological resources.

The application’s flowchart (

Figure 6) reflects an efficient design, minimizing unnecessary interactions and optimizing the user experience. The serialization of the model using Joblib and its local deployment on users’ devices eliminated the need for an internet connection, fulfilling one of the project’s core objectives.

This offline capability positions the tool as an accessible solution for small and medium-scale producers, aligning with studies such as Hinojosa [15], who emphasize the importance of functional technological tools without connectivity to enhance agricultural resilience.

3.4. Participatory Field Validation

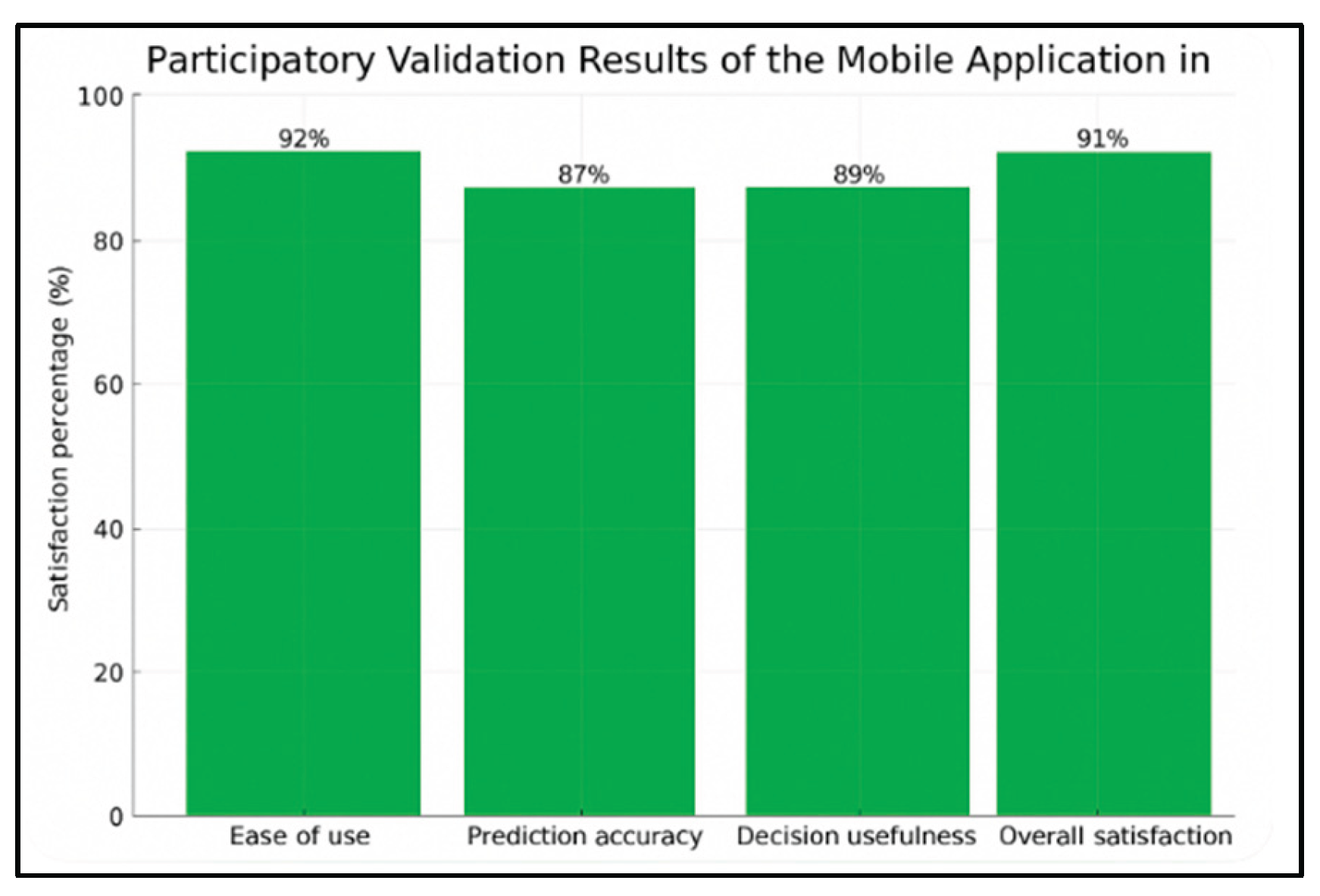

The application was validated in cacao-producing communities through functional testing, semi-structured interviews, and direct participatory observation. A sample of 60 farmers was selected based on their experience and willingness to adopt new technologies.

The results indicated a high level of satisfaction: 92% of users stated that the interface was easy to use, while 87% considered the predictions provided by the system to be accurate in relation to real field conditions. Additionally, 89% reported that the application was useful for making decisions regarding fertilization and harvesting, and finally, 91% expressed overall positive satisfaction with the system.

Additionally, users suggested improvements for future versions, such as the incorporation of weather alerts, automated recommendations based on expected yield, and post-harvest analysis features. These proposals reflect a progressive technological appropriation and the need to continue adapting the system to specific usage contexts, in accordance with user-centered design principles [16].

This qualitative and quantitative feedback confirms that digital technologies applied to the agricultural sector must not only be technically robust, but also culturally appropriate, sensitive to local context, and validated through participatory approaches to ensure effective adoption [17].

Figure 7 presents the aspects considered for the validation of the mobile application

3.5. Comparative Analysis with Previous Studies

To contextualize and validate the results obtained in the present study, a review of recent research applying machine learning techniques for agricultural yield prediction across various crops was conducted.

Table 2 summarizes the main characteristics of these studies, including the crop analyzed, the algorithm used, the reported performance metrics, and the applicability in offline environments.

The reviewed studies demonstrate the effectiveness of various machine learning techniques in predicting agricultural yield. For example, Fan and Zhan [18] applied the Random Forest algorithm to estimate rice yield in mountainous regions of China, achieving a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.85. In the context of maize cultivation, Baio [19] employed XGBoost and Random Forest algorithms, respectively, and obtained R² values of 0.94. In their study on cacao, they achieved similarly high predictive performance, further validating the applicability of these models to tropical crops.

Lamos [20] used Gradient Boosting and achieved an R² of 0.68 for cacao cultivation. Chaudhary [21] implemented a CNN-LSTM architecture for strawberry cultivation, achieving an R² of 0.89.

Comparatively, the XGBoost model developed in the present study achieved an R² of 0.996, surpassing the results reported in the aforementioned studies. Furthermore, unlike the reviewed research—which often requires advanced technological infrastructure and constant connectivity—our model was implemented in a fully functional offline mobile application, making it particularly suitable for use in rural areas with limited internet access.

The selection of XGBoost as the primary algorithm is justified not only by its high predictive performance but also by its interpretability and low computational cost. These characteristics facilitate its adoption by technicians and farmers without specialized training in data science, thereby promoting the effective transfer of technology to the agricultural sector. The comparison with previous studies (

Table 2) highlights the competitiveness and practical applicability of the proposed model, positioning it as a valuable tool for cacao yield prediction in similar contexts.

3.6. General Discussion

Araújo [22] highlights how machine learning, a crucial component of artificial intelligence, is revolutionizing agriculture by optimizing operations and improving resource management. In line with this, the results of this study demonstrate the transformative potential of artificial intelligence applied to agricultural forecasting in low-connectivity environments. The combination of sensors, machine learning, and mobile applications helps reduce uncertainty in agricultural planning, improve input use efficiency, and strengthen the resilience of production systems in the face of climate change.

According to Shamshiri [4], this study demonstrates that intelligent digitalization of agriculture is viable, effective, and scalable. The choice of an interpretable model such as the decision tree, combined with an offline mobile app, constitutes an appropriate solution for rural areas facing structural challenges related to connectivity and technological access.

4. Conclusions

The development of an offline mobile application based on artificial intelligence for cacao yield prediction represents a concrete step toward inclusive digitalization of agriculture in low-connectivity environments. Through the implementation of the CRISP-DM approach, this study successfully translated a process sensitive to environmental factors into a functional and accessible model for small scale producers. The integration of sensors, machine learning techniques, and low-resource computational tools enabled the construction of a robust, technically sound, and socially relevant solution.

The results demonstrate that it is possible to combine methodological rigor with technological usability criteria in rural communities without relying on advanced digital infrastructure. Beyond the technical performance of the predictive model, this work highlights the transformative potential of AI when it is designed from a logic of local appropriation rather than external imposition. The positive acceptance of the system in everyday agricultural decision making reflected in the fact that 91% of users expressed overall satisfaction underscores its practical impact and its potential for scalability in other rural contexts.

This study thus contributes to the development of precision agriculture adapted to the Latin American context and establishes a replicable foundation for future initiatives aimed at strengthening productive resilience through data science. It opens a line of research for the incorporation of multivariate models with phenological and climatic forecasting, as well as the scaling of the application to other regions and crops facing similar structural limitations.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to published version of the manuscript.

Founding

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to published version of the manuscript.

Founding

Fund for Agrobiodiversity, Seeds, and Sustainable Agriculture (FIASA)

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the Universidad Técnica de Cotopaxi, La Maná Extension, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, and to the Research Fund for Agrobiodiversity, Seeds, and Sustainable Agriculture (FIASA) for supporting this work through the project “Agro-productive systems of Fabaceae in association with cacao and coffee within a circular economy context for sustainable development”.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Charry, A., Perea, C., Ramírez, K., Zambrano, G., Yovera, F., Santos, A., ... & Pulleman, M., «La economía agridulce de los diferentes sistemas de producción de cacao en Colombia, Ecuador y Perú.,» Agricultural Systems, 2025.

- Mohan, R. J., Rayanoothala, P. S., & Sree, R. P., «Next-gen agriculture: integrating AI and XAI for precision crop yield predictions.,» Frontiers in Plant Science, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pineda, Medina, D., Miranda Cabrera, I., de la Cruz, R. A., Guerra Arzuaga, L., Cuello Portal, S., & Bianchini, M., «A mobile app for detecting potato crop diseases.,» Journal of Imaging, p. 10(2), 2024.

- Shamshiri, R. R., Sturm, B., Weltzien, C., Fulton, J., Khosla, R., Schirrmann, M., ... & Hameed, I. A., «Digitalization of agriculture for sustainable crop production: a use-case review.,» Frontiers in Environmental Science, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Schröer, C., Kruse, F., & Gómez, J. M., «A systematic literature review on applying CRISP-DM process model.,» Procedia Computer Science, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fan, C., Chen, M., Wang, X., Wang, J. y Huang, B., «A review on data preprocessing techniques toward efficient and reliable knowledge discovery from building operational data.,» Frontiers in energy research, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D., Warrens, MJ y Jurman, G., «The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation.,» Peerj computer science, 2021.

- Yu, K., Liu, Y., & Sharma, A., «Analyze the effectiveness of the algorithm for agricultural product delivery vehicle routing problem based on mathematical model.,» International Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Information Systems (IJAEIS),, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. C., Dewi, C., Huang, S. W., & Caraka, R. E., «Selecting critical features for data classification based on machine learning methods.,» Journal of Big Data., 2020. [CrossRef]

- Joshua, V., Priyadharson, S. M., & Kannadasan, R., «Exploration of machine learning approaches for paddy yield prediction in eastern part of Tamilnadu.,» Agronomy, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pechlivani, E. M., Gkogkos, G., Giakoumoglou, N., Hadjigeorgiou, I., & Tzovaras, D., «Towards sustainable farming: a robust decision support system’s architecture for agriculture 4.0.,» International Conference on Digital Signal Processing (DSP), 2023.

- Hacinas, E. A. S., Querol, L. S., Santos, K. L. T., Matira, E. B., Castillo, R. C., Arcelo, M., ... & Rustia, D. J. A., «Rapid Automatic Cacao Pod Borer Detection Using Edge Computing on Low-End Mobile Devices.,» Agronomy, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nti, IK, Zaman, A., Nyarko-Boateng, O., Adekoya, AF y Keyeremeh, F., «A predictive analytics model for crop suitability and productivity with tree-based ensemble learning.,» Decision Analytics Journal, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jo, J. S., Kim, D. S., Jo, W. J., Sim, H. S., Lee, H. J., Moon, Y. H., ... & Kim, S. K., «Prediction of strawberry fruit yield based on cultivar-specific growth models in the tunnel-type greenhouse,» Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology, 2022.

- Hinojosa, C., Sanchez, K., Camacho, A., & Arguello, H., «AgroTIC: Bridging the gap between farmers, agronomists, and merchants through smartphones and machine learning.,» arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12418., 2023.

- J. Lowenberg DeBoer, «Economics of adoption for digital automated technologies in agriculture.,» AgEcon SEARCH RESEARCH IN AGRICULTURAL & APPLIED ECONOMICS, 2022.

- T. Marinchenko, Digital transformations in agriculture. In Complex Systems: Innovation and Sustainability in the Digital, Cham: Springer International Publishing., 2021.

- Fan, L.; Fang, S.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, L, «Rice Yield Estimation Using Machine Learning and Feature Selection in Hilly and Mountainous Chongqing, China,» Agriculture, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Baio, F. H. R., Santana, D. C., Teodoro, L. P. R., Oliveira, I. C. D., Gava, R., de Oliveira, J. L. G., ... & Shiratsuchi, L. S., «Maize yield prediction with machine learning, spectral variables and irrigation management.,» Remote Sensing, 2022.

- Lamos, Díaz, H., Puentes Garzón, DE, & Zarate Caicedo, DA, «Comparación entre modelos de aprendizaje automático para pronóstico de rendimiento en cultivos de cacao en santander, Colombia.,» Revista Facultad de Ingeniería, 2020.

- Chaudhary, M., Gastli, MS, Nassar, L. y Karray, F., «Deep Learning Approaches for Forecasting Strawberry Yield and Prices Using Satellite Imagery and Station-Based Soil Parameters.,» Preimpresión de arXiv:2102.09024, 2021.

- Araújo, S. O., Peres, R. S., Ramalho, J. C., Lidon, F., & Barata, J., «Machine learning applications in agriculture: current trends, challenges, and future perspectives.,» Agronomy, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).