1. Introduction

Surfing is an aquatic sliding sport that demands muscular strength, balance, and flexibility, enabling the surfer to stay on the board and make the necessary adjustments according to the maneuvers being performed and the behaviour of the wave [

1].

As an outdoor sport, it not only benefits physical health but also mental health, promoting concentration, coordination, and stress reduction [

2]. Exercising outdoors is associated with improvements in mental health [

3], and the complex aquatic environment requires the development of postural control strategies involving visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems [

4].

These capacities are essential for adapting the body to the anterior-posterior and lateral demands generated when maneuvering on a surfboard in an unstable, slippery environment [

1,

4,

5]. The vestibular system, in particular, provides information on the body’s orientation relative to the environment, influencing athletic performance and safety during both training and competition. It plays a key role in both static and dynamic balance [

5,

6].

Sports requiring constant balance also improve postural control, which is a limiting factor in performance, since no technical sports movement whether at an amateur or professional level can be efficiently executed without effective postural balance control [

7]. Surfing additionally involves the dynamic nature of waves, requiring continuous adjustment, and demands prior experience and situational awareness for adequate balance strategies [

1,

4,

5].

Moreover, the psychological benefits of physical activity suggest that sports such as surfing can positively influence self-esteem and overall wellbeing in children and adolescents [

8,

9,

10]. In a rehabilitation context, including activities that simultaneously offer physical and psychological benefits could maximise treatment outcomes by providing an enjoyable environment for exercise in nature, reducing stress, and enhancing self-perception [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Surfing may also play a pivotal role in preventing musculoskeletal injuries due to the physical demands of the sport, including significant strengthening of the core and stabilising muscles. These adaptations, combined with the inherent balance challenge in surfing encompassing both static and dynamic balance may be beneficial for patients recovering from physical or psychological injuries [

12,

13].

The benefits of surfing are not limited to the physical realm; the marine environment in which it is practiced also contributes to improved mood and reduced anxiety levels, as confirmed by recent research into water sports [

14,

15,

16]. Aquatic-based rehabilitation techniques have also been shown to improve both static and dynamic balance in adults [

17].

This study aims to evaluate and compare levels of balance among individuals who practise surfing and people with varying levels of physical activity. It also seeks to determine whether there is a direct relationship between sports practice and self-esteem, thereby assessing the potential role of surfing as a therapeutic tool in clinical contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

In this cross-sectional study, 138 healthy Caucasian individuals aged 18 to 55 were recruited. Thirteen participants were excluded for not meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria, resulting in a final total of 124 participants. Exclusion criteria for the total sample included: having any balance disorder, not fitting the established age range (2 participants), experiencing lower-limb musculoskeletal injuries in the past two years (3 participants), suffering from any major visual or auditory impairment (such as blindness, vertigo, or deafness), having an oncological or neurological illness, or taking medication that could affect balance (3 participants). Pregnancy was also an exclusion criterion, along with failing to complete the requested questionnaires fully (5 participants).

All participants were instructed not to perform any physical exercise within 24 hours prior to the assessments to eliminate any potential influence on the results. They were informed of the study protocol and the associated risks/benefits, and they signed informed consent forms. They also retained the right to withdraw from the study at any time, although none chose to do so. All procedures were approved by an Institutional Ethics Review Committee. Ref. UCAGM 3/23 (University of Cádiz, Spain) in accordance with current national and international laws and regulations for human subjects (Declaration of Helsinki, Fortaleza, Brazil, 2013). All data were recorded anonymously and handled in strict compliance with Spanish data protection laws (Law 41/2002 of 14 November and Law 15/1999 of 13 December).

The participants were divided into three groups: Group 1 (G1): 42 surfers (31 men, 11 women; mean age = 29.7 ± 8.8 years; surfing experience = 11.05 ± 10.12 years). Inclusion/exclusion criteria for G1 required at least two years of surfing experience and at least 3 hours of physical activity included surfing; participants were permitted to practise other sports. Individuals with visual and/or auditory impairments (myopia or hypoacusis) were included as long as those conditions were well managed.

Group 2 (G2): 43 individuals performing more than 3 hours of weekly physical activity (28 men, 15 women; mean age = 25.0 ± 8.42 years). Inclusion criterion: Practising a minimum of 3 hours of physical activity per week, excluding surfing.

Group 3 (G3): 39 individuals performing fewer than 3 hours of weekly physical activity (18 men, 21 women; mean age = 23.3 ± 5.6 years). Inclusion/exclusion criteria for G3 required that participants practise 3 or fewer hours of physical activity per week and not engage in surfing.

2.2. Measures

All measurements were taken in April 2024. Each participant attended one assessment session. They were contacted through email sent to surf centres and schools, and via posters placed in universities, university schools, surf clubs, and various sports facilities. These emails provided detailed information about the tests and questionnaires. All instruments employed in this study have scientific validation.

Body Mass Index (BMI): Height and body mass were measured while participants were barefoot, wearing shorts and a t-shirt. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (Holtain, Crymmych, UK), and body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a Seca scale (SECA 861, Leicester, UK). Instruments were calibrated for accuracy. BMI was calculated as body mass (kg) divided by stature squared (m²).

Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT): This test is widely used to assess dynamic stability and proprioception, having been validated for various populations with high reliability [

18,

19,

20,

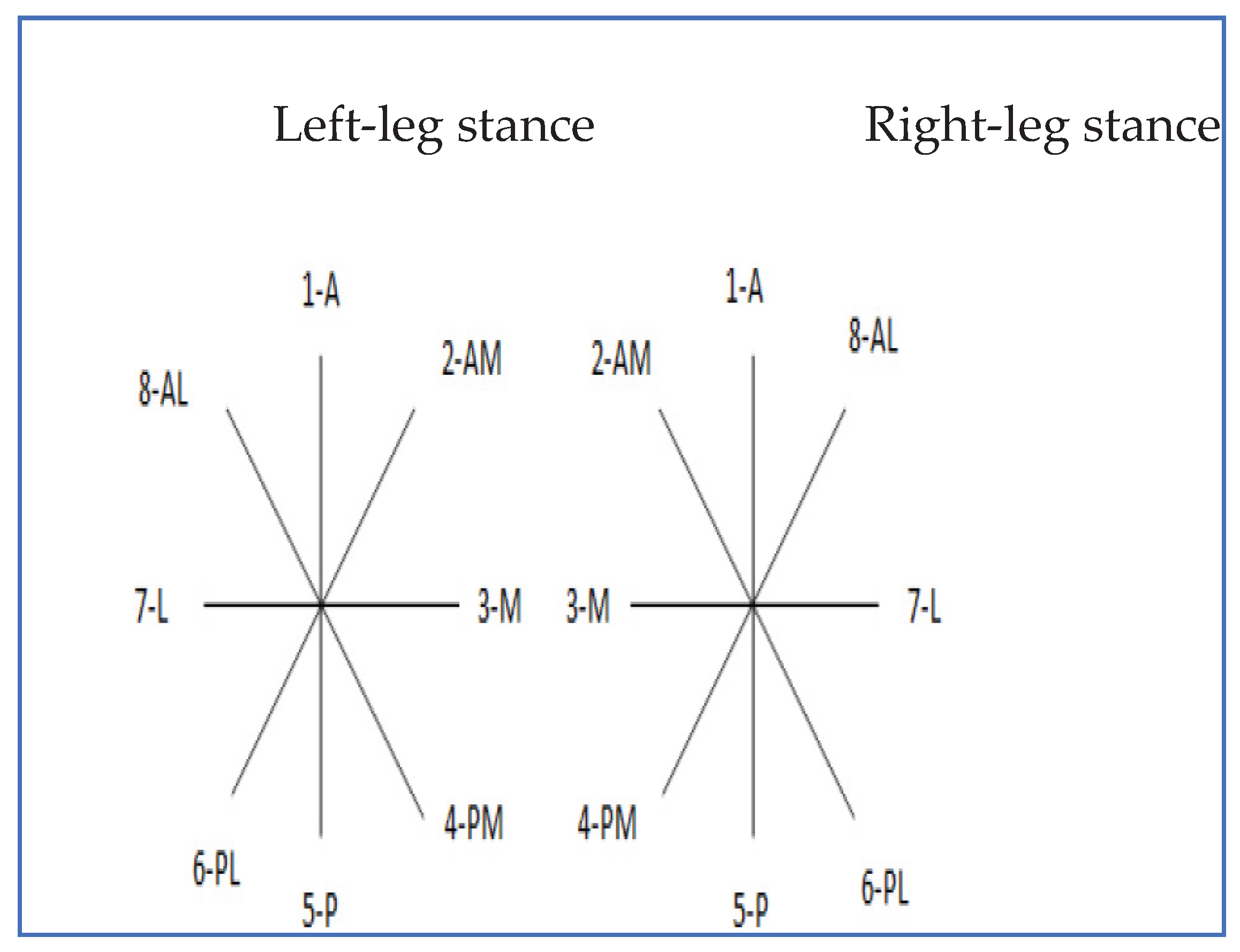

21]. Eight metric lines were placed on the floor, arranged like a star with 45° angles between them, each line ranging from 200 to 250 cm in length. Two calibrated lines were first placed in vertical and horizontal orientations (forming a symmetrical cross), followed by two diagonal lines in the shape of an “x”, all intersecting at the same central point. Each arm was labelled according to the direction in which the leg should move. Before starting the test, the length of both lower limbs was measured from the highest point of the anterior superior iliac spine to the centre of the fibular malleolus (

Figure 1).

During the test, participants stood at the intersection point of all lines on one leg (single-leg stance), keeping the supporting foot oriented towards the anterior direction of the star (1-A). The supporting foot remained in full contact with the floor without shifting or lifting the heel. With the other foot, participants reached as far as possible, touching the floor lightly with the tip of the big toe in each of the eight directions, returning to the starting point before moving on to the next direction. When the tested foot was the left foot, the sequence began in the anterior direction and proceeded clockwise; with the right foot, it progressed anticlockwise. The farthest point reached was recorded, and this test was performed twice per leg, with a 2-minute rest between trials.

To determine the final score, the mean of all measurement results was divided by eight times the total leg length and then multiplied by 100 to obtain a percentage. Two quantitative variables thus emerged: the result for the left leg (SEBT left) and the result for the right leg (SEBT right).

Flamenco Test: This simple, reliable test assesses static balance and is used in both clinical and sports contexts [

22]. The starting position involved placing one foot on the floor and the other on a 4 × 2 × 45 cm metallic board, secured at both ends by wooden supports, elevating it 8.5 cm above the floor. On a given signal, participants adopted a single-leg stance on the board, bending the free leg and holding it with the hand on the same side. The stopwatch began running when the participant was balanced on the board and was stopped whenever they lost balance (with either foot contacting the ground). Each time balance was lost, the participant resumed the starting position, and timing continued until a total of 1 minute on the board was reached. The number of falls from the board in that minute was recorded. If participants fell more than 15 times in the first 30 seconds, the test was terminated. The test was performed twice with a 1-minute rest between attempts.

Rosenberg Scale: Originally developed to assess self-esteem, this scale has shown utility in evaluating psychological factors and emotional wellbeing [

23,

24,

25]. Each participant completed a validated questionnaire (10 items) prior to the balance tests. Of these 10 items, 5 are worded positively and 5 negatively, measuring the individual’s feeling of satisfaction with themselves.

For items 1 to 5, the responses from A to D were scored 4 to 1, respectively, while for items 6 to 10, the responses from A to D were scored 1 to 4. The results were interpreted as follows: 30–40 points indicates high self-esteem, 26–29 average self-esteem, and below 25 low self-esteems.

Physical Activity and Sports History: The level of physical activity was measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ, 2011) [

26], which, among other items, queries the frequency and duration (at least 10 minutes per episode) of physical activity over the last seven days. Participants were also asked if they were members of any sports federation or had engaged in regular sports practice in the past two years. This questionnaire was supplemented with questions about surfing experience and weekly surfing frequency. Based on the information provided, each participant was classified as physically active or inactive.

Hamstring Flexibility: This component was evaluated using the Sit and Reach Test (SRT) following the established protocol [

27]. This test has high validity and reliability [

28,

29] and is one of the most commonly used linear methods [

30]. In the SRT, initially described by Wells & Dillon [

27], participants sat on the floor with legs together and extended, feet flexed at 90º against a measurement box marked with a ruler (PO Box 1500, Fabrication Enterprises Inc., White Plains, NY, USA). Participants wore sports clothing (top and shorts) without shoes. With palms facing downwards and fingers extended, they were instructed to reach forward as far as possible, sliding their hands along the ruler, holding the position for at least two seconds. The SRT score (in cm) was recorded as the final position reached by the fingertips on the ruler, with higher scores indicating better performance. The test was performed twice and the higher score was recorded [

29,

30,

31].

2.3. Procedure

Upon arriving at the assessment area and prior to the balance and flexibility tests, participants completed questionnaires on health habits, physical activity (IPAQ), and self-esteem (Rosenberg Scale). They also signed an informed consent form regarding their participation and permission to be recorded during the tests. All tests were conducted indoors under stable climatic conditions, with the ambient temperature between 22º and 24º. Each participant performed a short warm-up consisting of 5–10 minutes on a stationary bicycle or jogging.

Additionally, participants completed a questionnaire on their age, sex, occupation, sports activities (type and duration), surfing experience, history of trauma or pathologies, unhealthy habits, medications taken, and any relevant personal history.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive characteristics were reported as mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables and frequencies and percentage for qualitative variables. One-way ANOVA and chi-squared tests were conducted to examine differences in the descriptive characteristics between groups for quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively. ANCOVA was performed with age and sex as covariates to assess differences between groups in test results. RSES differences were modeled using a multinomial logistic regression with group category as main predictor and age and sex as covariates.

All model assumptions were verified prior to analysis. When significant main effects were found, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Bonferroni correction. A significance level of α = 0.05 was set for all hypothesis testing. All analyses were conducted using the R programming language for statistical computing (version 4.2.2).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 124 healthy male and female aged 18 to 55 took part in this study (77 male). Participant characteristics in each category were classified as G1 (29.7 ± 8.8 years), with a mean of 11.05 ± 10.12 years of surfing experience; G2 (25.0 ± 8.42 years); and G3 (23.3 ± 5.6 years). , G1 participants were significant older than G2 and G3 (p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively). Moreover, there was a higher proportion of females in G3 than in G1 and G2 (p < 0.05).

Table 1 summarises the characteristics for the overall group. The mean (±SD) BMI values recorded were 24.0 ± 4.5 for the whole group, 24.1 ± 3.4 for female, and 23.8 ± 3.2 for male.

3.2. Balance Tests

For the test variables, G1 obtained significantly higher results in SEBT-left leg than G2 and G3 (p < 0.001) and higher result in SEBT-right leg and FBT than G3 (p < 0.05).

Regarding the Star Excursion Balance Test, the greatest reach distances and highest averages for each leg were recorded in the surfer group compared to the other two groups. In the Flamenco Test, higher scores correspond to more falls, which implies poorer performance. G3 members exhibited the highest number of falls.

Table 2 displays the descriptive results for each group and the different balance tests.

The SEBT for the left leg, when comparing the three groups, no significant differences were found between G1 and G2, though differences did exist between G1 and G3. In comparing all three groups in the Flamenco Test, a significant difference emerged between surfers and both other groups (p < 0.05). The difference between G2 and G3 was not significant.

In addition, the relationship between the balance tests and age was examined to see if older or younger participants performed better or worse. The results showed no relationship between age and performance in both balance tests.

3.3. Hamstring Flexibility

G1 obtained the lowest performance in the flexibility test compared to the other groups, which may be attributed to the lower proportion of women in this group. When analyzed by sex, women significantly outperformed men in the flexibility test (p < 0.001), despite men reporting higher levels of physical activity (p < 0.05). In the sit-and-reach test (SRT), women achieved a mean score of 5.3 ± 5.1 cm, while men scored 2.1 ± 5.3 cm. These differences may be explained by biological or hormonal factors associated with sex. No significant positive correlations were found with other measured variables.

3.4. Self-Esteem

Concerning the Rosenberg Scale, 88.0% of G1 participants showed high self-esteem, 10.5% average self-esteem, and none low. In G2, 84.2% had high self-esteem, 15.7% average, and none low. In G3, 84.21% had high self-esteem, 10.5% average, and 5.2% low self-esteem. No differences were found across groups, nor was any association detected between sports practice and self-esteem.

4. Discussion

The present study links the practice of surfing to a significant improvement in both dynamic and static balance, compared to other populations and different sports disciplines. The findings indicate that sports requiring continuous adaptation to unstable environments strengthen postural control, as is the case in surfing, snowboarding, or ice hockey [

1,

4,

32,

33,

34]. These observations are supported by studies describing the physiological demands of surfing, emphasising not only the aerobic and anaerobic capacity required but also the importance of effective postural control to maintain balance on the board in constantly changing aquatic conditions [

35].

Constant exposure to unstable surfaces promotes proprioception and intermuscular coordination, encouraging more advanced postural strategies that could be harnessed in therapeutic contexts. The results demonstrate a significant difference in the SEBT (dynamic balance) between people who surf and those engaging in fewer than three hours of physical activity weekly. Notably, within the group performing under three hours of exercise per week, 12 participants did not perform any physical activity. Meanwhile, all participants in the surfer group also practised another sport, supporting the idea that better balance in this group is due to both surfing and regular physical activity. This aligns with a published study indicating that physical activity improves both static and dynamic balance compared to inactivity [

36].

No significant differences in dynamic balance were found between the group performing more than three hours of physical activity per week and the group performing fewer than three hours. This suggests that if practising any sport were the sole contributor to better balance, one would expect significant differences between these two groups. Hence, it is likely the practice of surfing that leads to improved dynamic balance.

Research has shown that proprioception, strength, and power are key components in aquatic sports like surfing, where ongoing exposure to unstable surfaces enhances intermuscular coordination and reflex responses [

1,

4,

5,

37]. Surfing also exerts a positive impact on specific populations, with its physical, psychological, and social benefits demonstrated by extensive intervention programmes [

8,

9,

38]. Additionally, aquatic physiotherapy research has documented similar improvements albeit in a less challenging setting for rehabilitation, achieving significant advances in postural control and general mobility of the treated area [

39,

40,

41].

With respect to balance, studies have compared dynamic balance, measured by the Star Excursion Balance Test, among hockey and football players. For instance, Bhat and Ali-Moiz [

42] found no significant differences between the two groups, suggesting that better balance may be linked to sports participation in general rather than the specific type of sport. This was also observed in our study, where the surfing group reported engaging in another sport as well.

However, focusing on the development of dynamic lower-limb strength, the SEBT appears to be a solid adjunct for detecting bilateral performance differences, possibly indicating the efficacy of surfing training in reducing lower-limb asymmetry and improving postural control [

43].

Furthermore, Reed et al. suggested that regular outdoor sports practice may help alleviate stress [

10,

44], a benefit that also appears in surfing through its combination of physical exercise and contact with nature. This highlights the potential of surfing not just as a recreational pursuit but also as a therapeutic tool. It aids not only balance and coordination but also provides a relaxing environment that may counteract chronic stress.

Regarding self-esteem, measured by the Rosenberg Scale, most participants scored in the high range, so this study did not find a relationship between sports practice and self-esteem. These findings are consistent with Molina-García et al. [

45], who likewise found no significant differences between physically active and inactive participants for both sexes. Compared to a study by Monteiro et al., no significant differences in self-esteem were observed between those who did and did not practise dance [

46]. Nevertheless, surfing could contribute to reducing depressive symptoms, which, in turn, may be related to improvements in self-esteem [

47].

As for hamstring extensibility, our study found that women surfers exhibited greater flexibility than their male counterparts. These data match other studies using the SRT [

28,

29,

30], and this difference could be due to biological or hormonal factors related to sex. However, we did not observe significant differences with other variables.

Our findings indicate that longitudinal studies are warranted to assess the long-term benefits of surfing across different populations. Future studies might explore how to combine surfing with other conventional aquatic therapies to maximise proven benefits [

40,

41]. Investigations should also delve into the psychological mechanisms that enhance balance and self-esteem and consider designing personalised interventions for specific clinical groups.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study confirms that practising surfing and physical activity improves both dynamic and static balance in healthy individuals. However, within the age ranges studied, no definitive relationship was found between age and balance performance. Regarding self-esteem, no differences were detected between surfers and other participants, though further research is needed to corroborate this finding. Moreover, the potential therapeutic applications of surfing for populations with balance disorders were highlighted.

A review of the literature suggests that this approach could offer a solid foundation for future research and for integrating surfing into innovative rehabilitation protocols. Surfing may serve as a complementary technique in rehabilitative treatments for patients with balance disorders, and further studies should explore these benefits in clinical settings.

6. Limitations

This study has several limitations worth noting. Firstly, its observational, cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between surfing practice and improved balance. Longitudinal or experimental designs would provide a clearer picture of how surfing influences balance and whether this effect persists over time. Secondly, participants were recruited from a single geographical region, which may affect the generalisability of the findings to broader or more diverse populations. Thirdly, self-reported data on physical activity (e.g., hours of exercise per week) could introduce recall bias or inaccuracies that affect the reliability of group classification.

Additionally, the environmental variability in surfing conditions (e.g., wave height, water temperature, or currents) was not standardised, potentially influencing the magnitude of balance adaptations. Finally, although the age range was fairly broad (18–55), the sample did not include individuals with clinically diagnosed balance disorders or other relevant comorbidities, limiting the application of these results to more specialised or clinical populations. Future research addressing these limitations such as conducting randomised controlled trials, recruiting more diverse cohorts, and systematically monitoring environmental factors would help confirm and extend the conclusions drawn here.

7. Practical Applications

Despite these limitations, the findings offer several practical applications. Firstly, surfing-based exercise programmes may be considered as an adjunct to traditional balance training for healthy adults, given the positive effect observed on dynamic and static balance. Health and fitness professionals could incorporate surf-specific drills or balance-related manoeuvres (e.g., simulation training on unstable surfaces) into broader exercise regimens to enhance postural control.

Secondly, sports coaches and athletic trainers can use surf-like training environments (e.g., surf simulators, balance boards) to diversify their athletes’ conditioning routine, potentially improving proprioception and postural stability.

Thirdly, the data suggest that long-term participation in an activity requiring dynamic postural adjustments (such as surfing) might confer benefits in daily tasks that involve balance and coordination, which could be particularly relevant for injury prevention in other sports.

Finally, although not tested directly in clinical populations, the results hint that surf-related activities may hold therapeutic potential for individuals undergoing rehabilitation for mild balance disorders. Engaging and enjoyable physical activities could facilitate greater adherence to rehabilitation protocols and potentially accelerate improvements in postural control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; GDC-M; MRR; MRV. Methodology, GDC-M; JRFS Writing GDC-M; JRFS. Original Draft Preparation, GDC-M; MRR, AT, Visualization and investigation, MRR; AT; GDC-M; MRV Data curation and supervision, JRF-S, Writing- reviewing and edition, GDC-M; AT; MRV; JRFS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants in this study, including university students and surf schools, as well as the technical coaches of surf clubs, for their generous time and effort.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Secomb, J. L., Farley, O. R. L., Lundgren, L., Tran, T. T., King, A., Nimphius, S., & Sheppard, J. M. Associations between the Performance of Scoring Manoeuvres and Lower-Body Strength and Power in Elite Surfers. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 2015. 10(5), 911-918. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C., Cooper, M.A. Mental health contribution to economic value of surfing ecosystem services. npj Ocean Sustain. 2023 2, 20. [CrossRef]

- Mahindru A, Patil P, Agrawal V. Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus. 2023 Jan 7;15(1):e33475. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chapman DW, Needham KJ, Allison GT, Lay B, Edwards DJ. Effects of experience in a dynamic environment on postural control. Br J Sports Med. 2008 Jan;42(1):16-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marigold DS, Patla AE. Strategies for dynamic stability during locomotion on a slippery surface: effects of prior experience and knowledge. J Neurophysiol. 2002 Jul;88(1):339-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrysomallis C. Balance ability and athletic performance. Sports Med. 2011 Mar 1;41(3):221-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcolin G, Supej M, Paillard T. Editorial: Postural Balance Control in Sport and Exercise. Front Physiol. 2022 Jul 12;13:961442. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Olive L, Dober M, Mazza C, Turner A, Mohebbi M, Berk M, Telford R. Surf therapy for improving child and adolescent mental health: A pilot randomised control trial. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2023 Mar;65:102349. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro L, Clemente FM, Claudino JG, Ferreira J, Ramirez-Campillo R, Afonso J. Surf therapy for people with mental health disorders: a systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2024 Oct 26;24(1):376. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reed K, Wood C, Barton J, Pretty JN, Cohen D, Sandercock GR. A repeated measures experiment of green exercise to improve self-esteem in UK school children. PLoS One. 2013 Jul 24;8(7):e69176. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moreira M, Peixoto C. Qualitative task analysis to enhance sports characterization: a surfing case study. J Hum Kinet. 2014 Oct 10;42:245-57. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Becker BE. Aquatic therapy: scientific foundations and clinical rehabilitation applications. PM R. 2009 Sep;1(9):859-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo RS, Cardeira CSF, Rezende DSA, Guimarães-do-Carmo VJ, Lemos A, de Moura-Filho AG. Effectiveness of the aquatic physical therapy exercises to improve balance, gait, quality of life and reduce fall-related outcomes in healthy community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023 Sep 8;18(9):e0291193. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- González-Devesa D, Vilanova-Pereira M, Araújo-Solou B, Ayán-Pérez C. Effectiveness of surfing on psychological health in military members: a systematic review. BMJ Mil Health. 2024 Oct 8 :military-2024-002856. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocher M, Silva B, Cruz G, Bentes R, Lloret J, Inglés E. Benefits of Outdoor Sports in Blue Spaces. The Case of School Nautical Activities in Viana do Castelo. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Nov 16;17(22):8470. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Godfrey C, Devine-Wright H, Taylor J. The positive impact of structured surfing courses on the wellbeing of vulnerable young people. Community Pract. 2015 Jan;88(1):26-9. [PubMed]

- Roth, A. E., Miller, M. G., Ricard, M., Ritenour, D., & Chapman, B. L. Comparisons of static and dynamic balance following training in aquatic and land environments. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 2006. 15(4), 299-311. [CrossRef]

- Powden CJ, Dodds TK, Gabriel EH. The reliability of the star excursion balance test and lower quarter y-balance test in healthy adults: a systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2019 Sep;14(5):683-694. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hyong IH, Kim JH. Test of intrarater and interrater reliability for the star excursion balance test. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014 Aug;26(8):1139-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gribble P, Hertel J. Considerations for normalizing measures of the Star Excursion Balance Test. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2003;7(2):89-100. [CrossRef]

- Gribble PA, Hertel J, Plisky P. Using the Star Excursion Balance Test to assess dynamic postural-control deficits and outcomes in lower extremity injury: a literature and systematic review. J Athl Train. 2012 May-Jun;47(3):339-57. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gergüz Ç, Aras Bayram G. Effects of Yoga Training Applied with Telerehabilitation on Core Stabilization and Physical Fitness in Junior Tennis Players: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Complement Med Res. 2023;30(5):431-439. English. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005 Oct;89(4):623-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieiro P, González-Rodríguez R, Domínguez-Alonso J. Self-esteem and socialisation in social networks as determinants in adolescents’ eating disorders. Health Soc Care Community. 2022 Nov;30(6):e4416-e4424. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zurita-Ortega F, Castro-Sánchez M, Rodríguez-Fernández S, Cofré-Boladós C, Chacón-Cuberos R, Martínez-Martínez A, Muros-Molina JJ. Actividad física, obesidad y autoestima en escolares chilenos: Análisis mediante ecuaciones estructurales [Physical activity, obesity and self-esteem in chilean schoolchildren]. Rev Med Chil. 2017 Mar;145(3):299-308. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallal PC, Victora CG. Reliability and validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004 Mar;36(3):556. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells K. F., & Dillon E. K. The sit and reach—A test of back and leg flexibility. Res Q. 1952 Mar;23(1):115–118. [CrossRef]

- Chillón P, Castro-Piñero J, Ruiz JR, Soto VM, Carbonell-Baeza A, Dafos J, Vicente-Rodríguez G, Castillo MJ, Ortega FB. Hip flexibility is the main determinant of the back-saver sit-and-reach test in adolescents. J Sports Sci. 2010 Apr;28(6):641-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponce-González JG, Gutiérrez-Manzanedo JV, De Castro-Maqueda G, Fernández-Torres VJ, Fernández-Santos JR. The federated practice of soccer influences hamstring flexibility in healthy adolescents: role of age and weight status. Sports. 2020 Apr 13;8(4):49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Manzanedo, J.V.; Fernández-Santos, J.R.; Ponce-González, J.G.; Lagares-Franco, C.; De Castro-Maqueda, G. Hamstring extensibility in female elite soccer players. Retos. Nuevas Tend. Educ. Fís. Deporte Recreac. 2018, 33, 175–178. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz J. R., Castro-Piñero J., Artero E. G., Ortega F. B., et al. Predictive validity of health-related fitness in youth: A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2009 Sep;43(12):909–923. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemková E, Kováčiková Z. Sport-specific training induced adaptations in postural control and their relationship with athletic performance. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023 Jan 12;16:1007804. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Behm DG, Wahl MJ, Button DC, Power KE, Anderson KG. Relationship between hockey skating speed and selected performance measures. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 May;19(2):326-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paillard T, Margnes E, Portet M, Breucq A. Postural ability reflects the athletic skill level of surfers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011 Aug;111(8):1619-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez-Villanueva A, Bishop D. Physiological aspects of surfboard riding performance. Sports Med. 2005;35(1):55-70. [CrossRef]

- Igual Camacho C, Serra Añó P, Alakdar Y, Cebriá MA, López Bueno L. Estudio comparativo del efecto de la actividad física en el equilibrio en personas mayores sanas. Fisioterapia. 2008; 30(3): 137-141. [CrossRef]

- Farley O, Harris NK, Kilding AE. Anaerobic and aerobic fitness profiling of competitive surfers. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 Aug;26(8):2243-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benninger, E., Curtis, C., Sarkisian, G. V., Rogers, C. M., Bender, K., & Comer, M. Surf Therapy: A Scoping Review of the Qualitative and Quantitative Research Evidence. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 2020, 11(2), 1–26.

- Veldema J, Jansen P. Aquatic therapy in stroke rehabilitation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021 Mar;143(3):221-241. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, Hagen KB, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Dagfinrud H, Lund H. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 23;3(3):CD005523. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peretro G, Ballico AL, Avelar NC, Haupenthal DPDS, Arcêncio L, Haupenthal A. Comparison of aquatic physiotherapy and therapeutic exercise in patients with chronic low back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2024 Apr; 38:399-405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat R, Moiz JA. Comparison of dynamic balance in collegiate field hockey and football players using star excursion balance test. Asian J Sports Med. 2013 Sep;4(3):221-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Silva B, Clemente FM. Physical performance characteristics between male and female youth surfing athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019 Feb;59(2):171-178. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton J, Pretty J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ Sci Technol. 2010 May 15;44(10):3947-55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina García J, Castillo Fernández I, Pablos C. Bienestar psicológico y práctica deportiva en universitarios. Eur J Hum Mov. 2007;18: 79-91.

- Monteiro LA, Novaes JS, Santos ML, Fernandes HM. Body dissatisfaction and self-esteem in female students aged 9-15: the effects of age, family income, body mass index levels and dance practice. J Hum Kinet. 2014 Nov 12;43:25-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hearn B, Biscaldi M, Rauh R, Fleischhaker C. Feasibility and effectiveness of a group therapy combining physical activity, surf therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy to treat adolescents with depressive disorders: a pilot study. Front Psychol. 2025 Feb 12;16:1426844. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).