Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

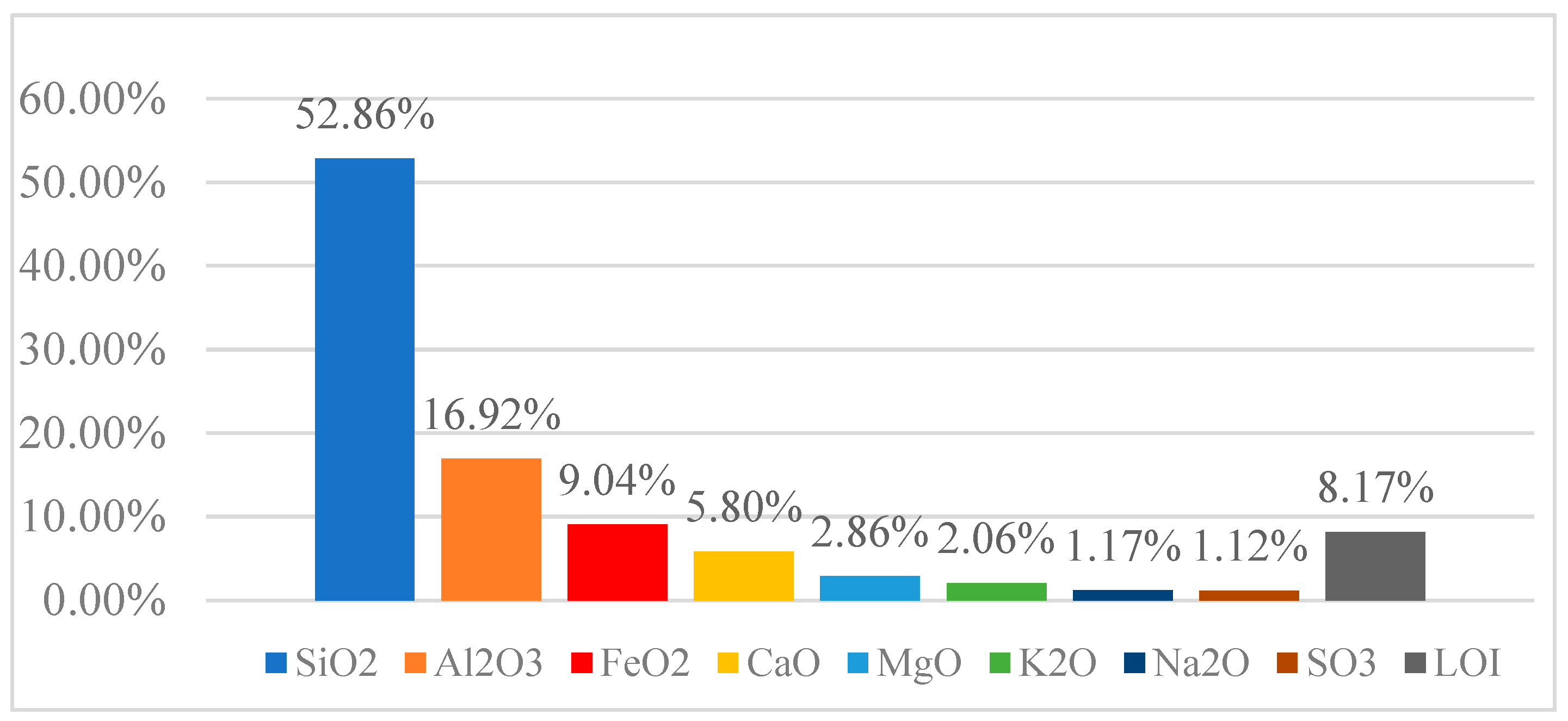

2.1. Mineralogical-Petrographic and Chemical Composition of the Raw Material

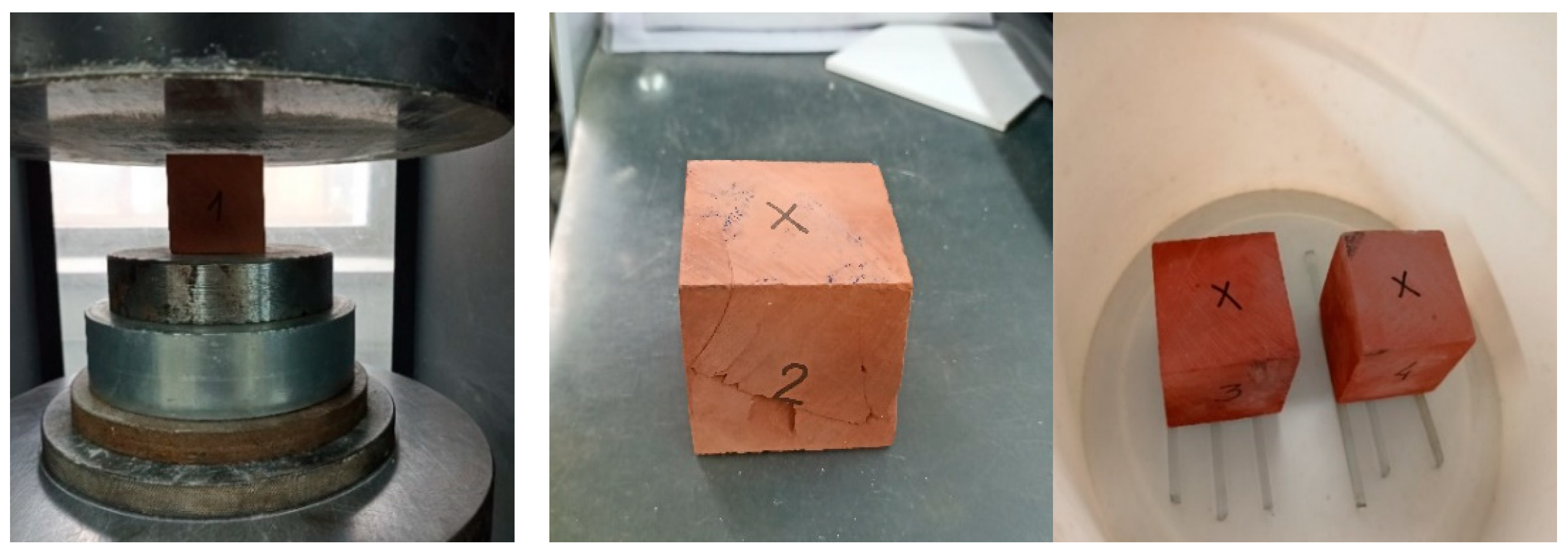

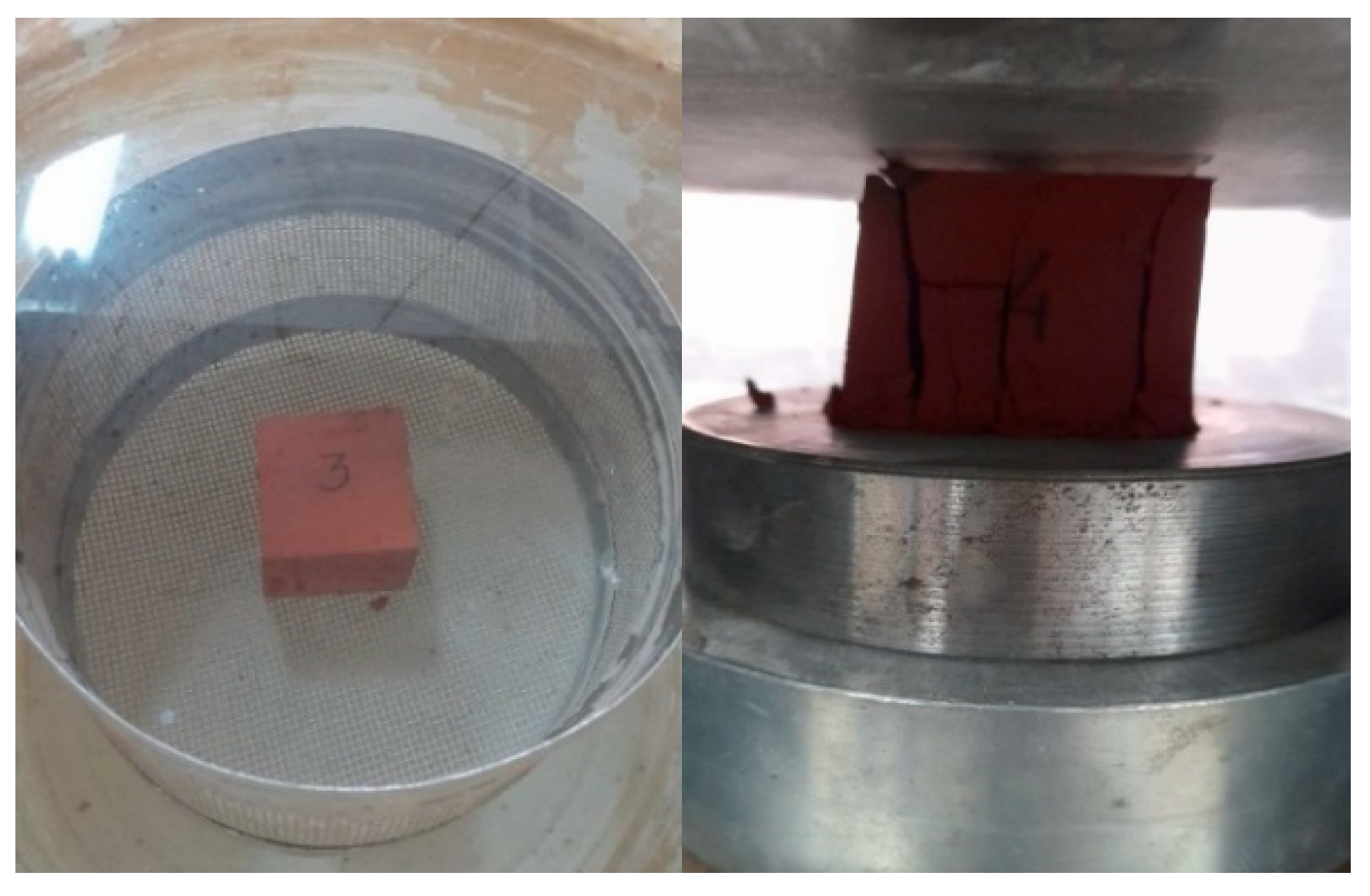

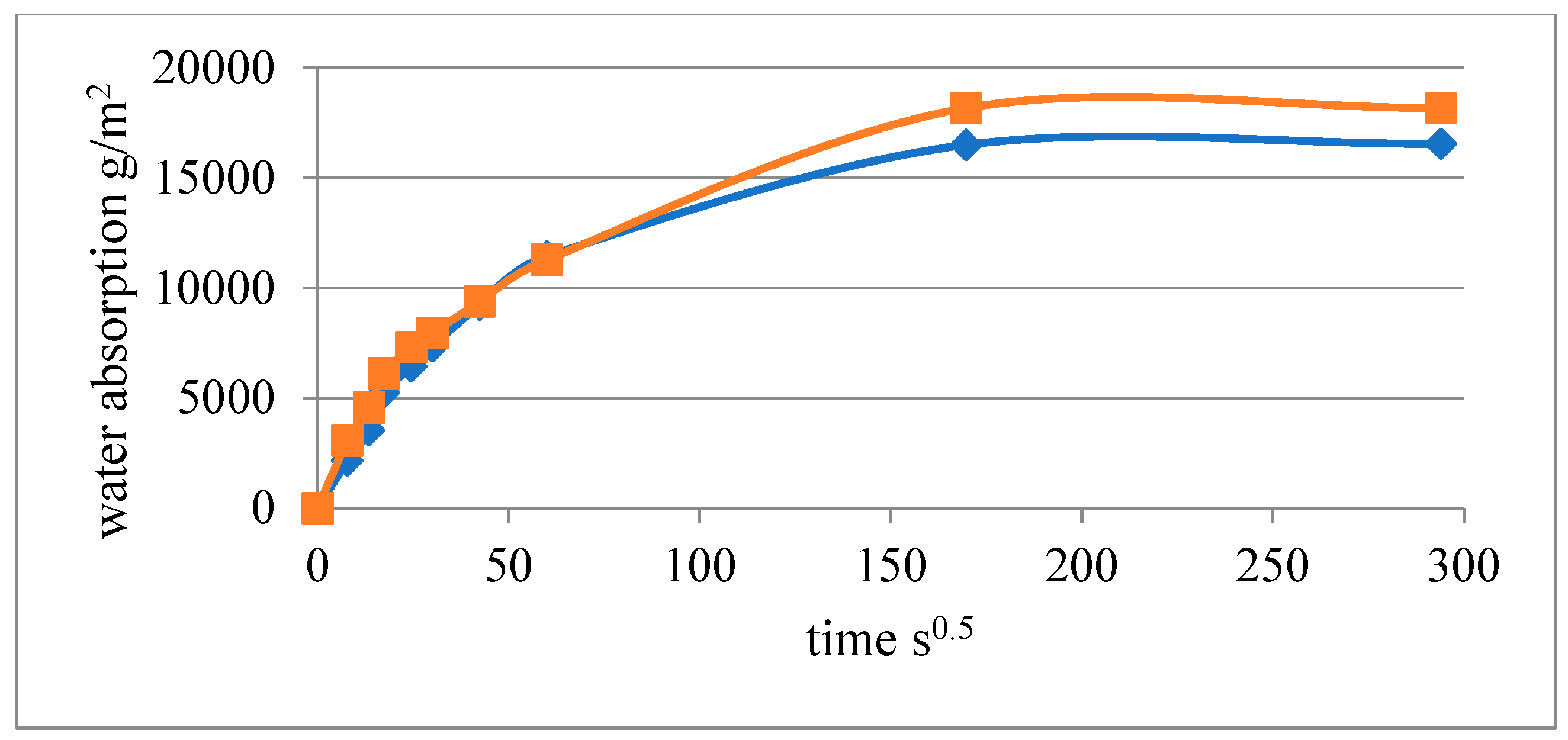

2.2. Physical – Mechanical Properties of Red Solid Clays

| Determination of water absorption coefficient by capillarity - MKS EN 1925 | Sample 3 | [g/m2 · s0.5] | 51,2 |

| Sample 4 | [g/m2 · s0.5] | 47,5 | |

| Average value | [g/m2 · s0.5] | 49,4 |

2.3. Composite Masonry Blocks

2.3.1. Materials for Blocks

2.3.2. Physical and Mechanical Properties of the Blocks

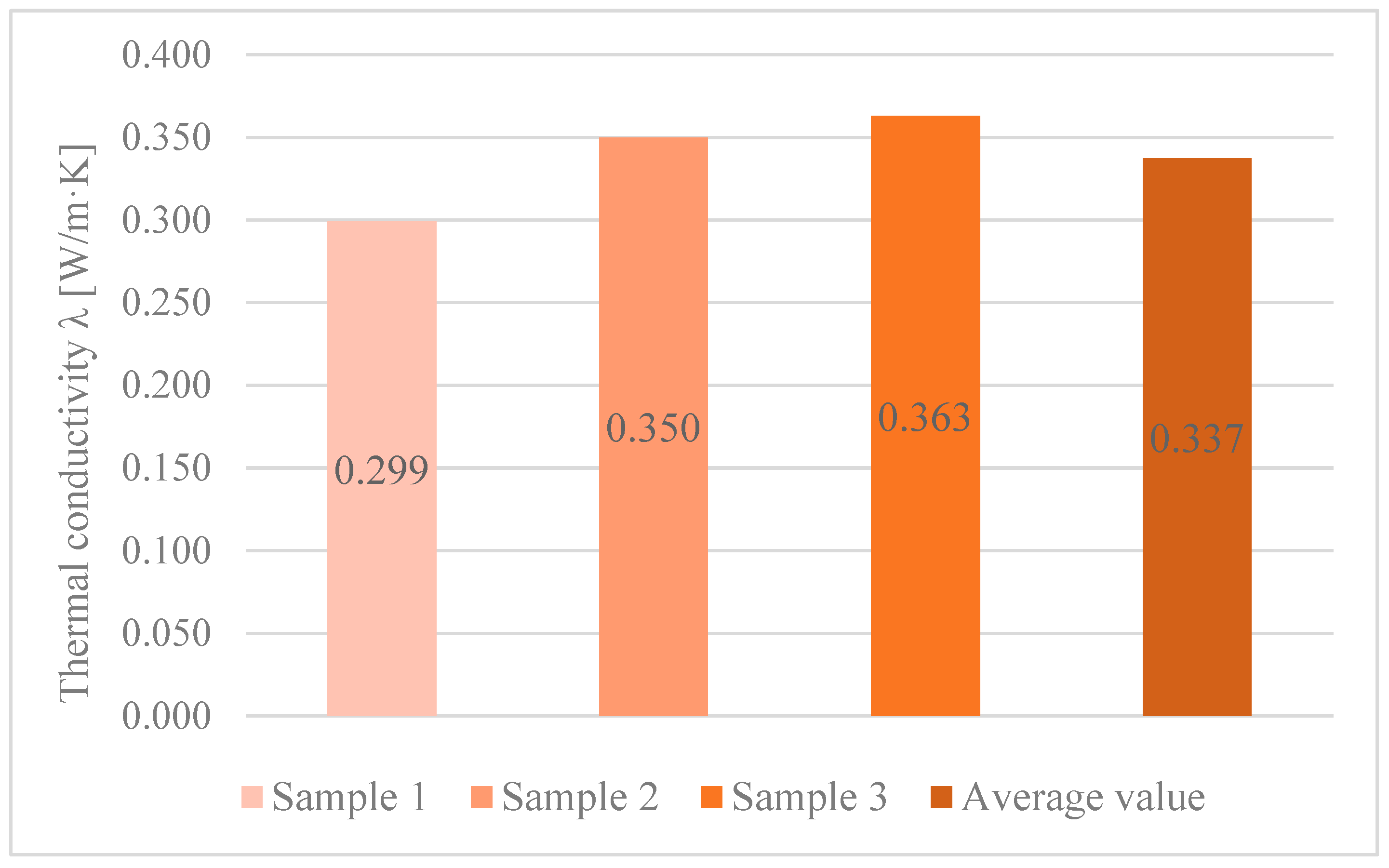

2.3.3. Thermal. Conductivity

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results for the Red Solid CLay

3.2. Results for the Composite Masonry Blocks

| Material | Average compressive strength [MPа] | Average net density [kg/m3] |

|---|---|---|

| Composite block with red solid clay (tested results) | 3,1 – 4,1 | 1600 – 1640 |

| Ordinary concrete block | 6,0 – 9,0 | 1800 – 2100 |

| Autoclaved lightweight concrete block | 2,5 – 7,0 | 400 – 700 |

4. Conclusions

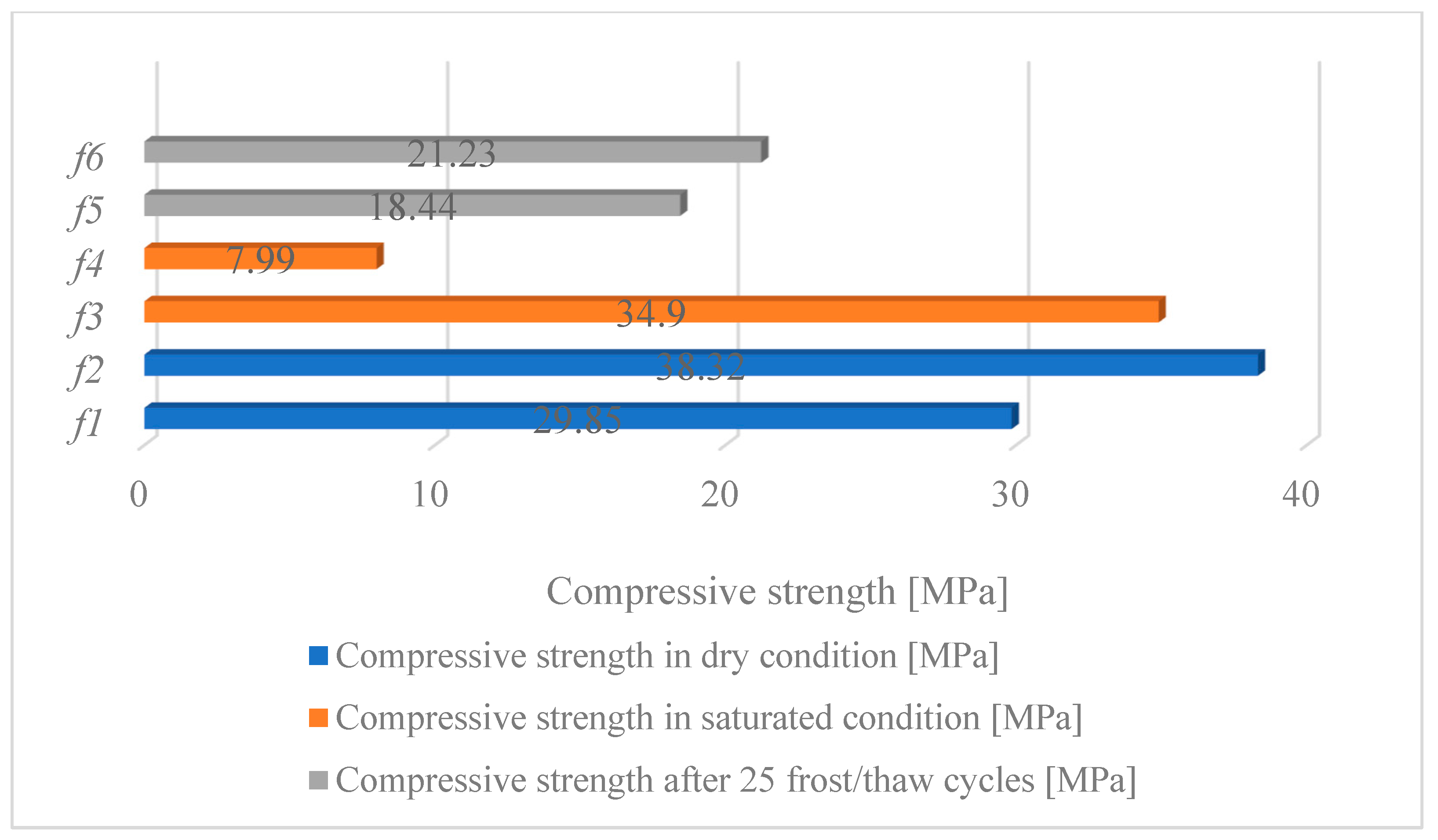

- − The cubes of the naturally baked red solid clay showed that this is a highly porous material, with a low density, a high percentage of water absorption and unexpectedly good strength properties.

- − Considering the high percentage of porosity of the red solid clay and the good results of compressive strength, it opens up the possibility of using the material as a building stone, especially in the production of composite masonry blocks.

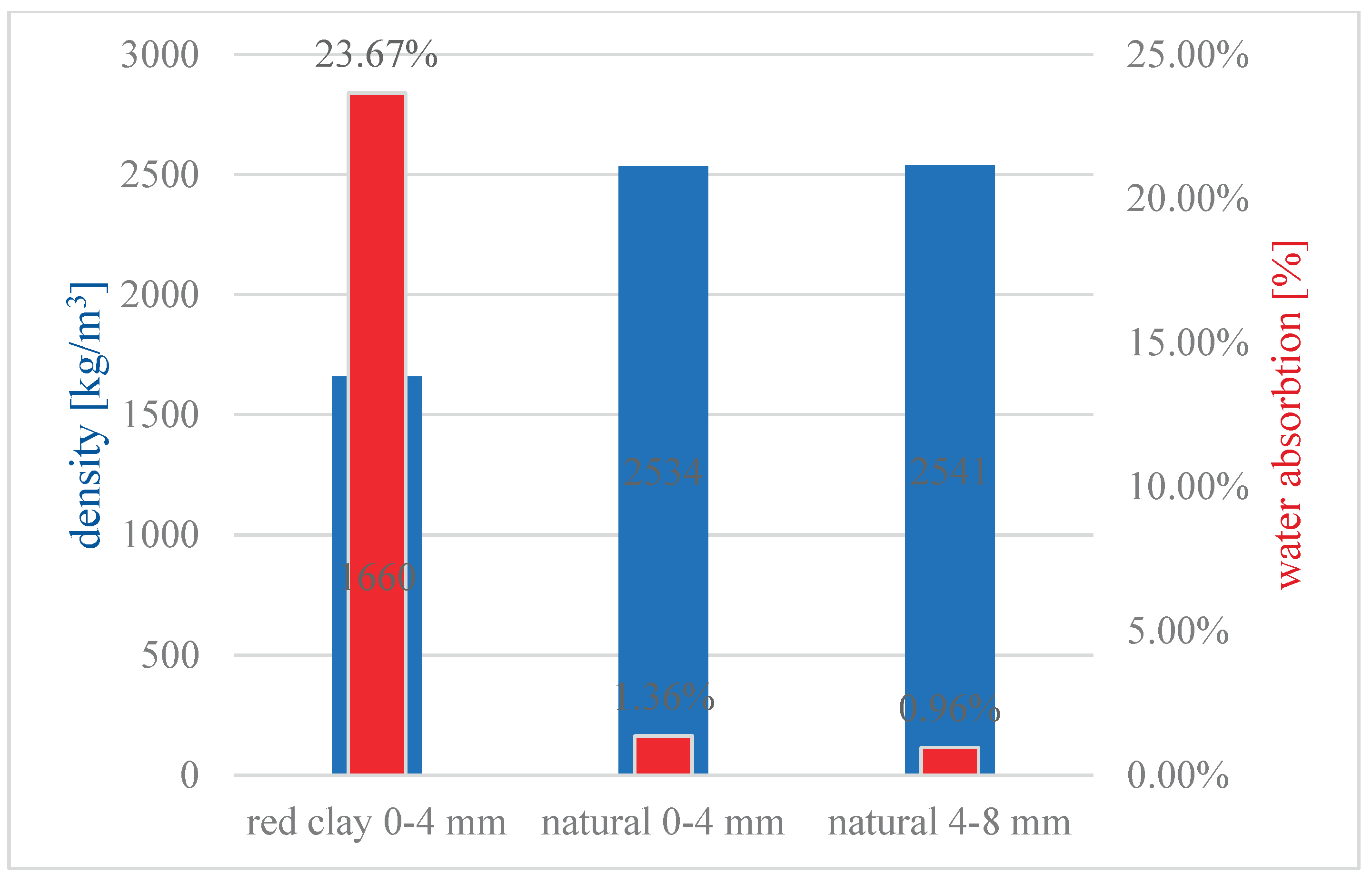

- − The density of red solid clay aggregate is significantly lower compared to the density of natural stone aggregate which is traditionally used for making traditional concrete blocks. Through the conducted tests, it has been proven that water absorption is also with a large percentage, i.e. a much higher percentage compared to the natural aggregate.

- − The compressive strength of tested types of composite blocks depends on the net density and the number of chambers (cavities). The 5-chamber block (type II) showed better compressive strength than the 6-chamber block, although a comparison of net densities showed that it had a lower net density. That means the Type II block is generally lighter than the Type I, yet has better compressive strength, due to the arrangement of the chambers.

- − Composite masonry blocks based on red solid clay have good strength-deformable properties, are lighter compared to traditional concrete blocks and have a high degree of porosity, which certainly brings improved thermal properties.

- − The negative side is the relatively high degree of water absorption, which makes the blocks unsuitable for use in wet environments, i.e. if they are used in conditions exposed to moisture, it is necessary to protect them with appropriate waterproofing.

- − Solid red clay composite blocks have a coefficient of thermal conductivity seven (7) times lower than traditional concrete blocks and about two (2) times lower coefficient than solid brick, which makes it a better insulator than these two traditionally used materials in the construction of buildings.

- − The composite masonry block with these properties can be used for building non-structural walls in smaller residential buildings, as well as larger industrial buildings, for building chimneys, fence walls, etc. The positive side is that the blocks are larger in size and make masonry faster and easier, while reducing the use of mortar.

Acknowledgments

References

- N. F. Arenas, M. N. F. Arenas, M. Shafique, “Reducing embodied carbon emissions of buildings – a key consideration to meet the net zero target”, Sustainable Futures, 7 (2024).

- N. N. Myint, M. N. N. Myint, M. Shafique, “Embodied carbon emissions of buildings: Taking a step towards net zero buildings”, Case Studies in Constr Materials, 20 (2024).

- F. Althoey, W. S. F. Althoey, W. S. Ansari, M. Sufian, A. F. Deifalla, “Advancements in low-carbon concrete as a construction material for the sustainable built environment”, Developments in the Built Environment, 16 (2023).

- T. Al-Ani, O. T. Al-Ani, O. Sarapää, Clay and clay mineralogy, Geological Survey of Finland 2008.

- S. Mukherjee, The Science of Clays, Springer, 2013.

- N. Lechner, Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects, John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- A.N. Adazabra, G. A.N. Adazabra, G. Viruthagiri, N. Shanmugam, “An assessment on the sustainable production of construction clay bricks with spent shea waste as renewable ecological material”, J Environ Waste Management and Recycling, 1 (2), (2018).

- M. Rasool, A. M. Rasool, A. Hameed, M. U. Qureshi, Y. E. Ibrahim, A. U. Qazi, A. Sumair “Experimental study on strength and endurance performance of burnt clay bricks incorporating marble waste”, J Asian Arch and Building Eng, 22(1), (2022) 240–255.

- T. Nuchnapa, M. T. Nuchnapa, M. Sopita, N. Atima, S. Watchara, S. Anuvat, “Enhancing physical-thermal-mechanical properties of fired clay bricks by eggshell as a bio-filler and flux”, Science of Sintering, 51(1), (2019), 1-13.

- A. Ansari, S. A. A. Ansari, S. A. Mangi, S. Khoso, K. L. Khatri, G. S. Solangi, “Latest Development in the Structural Material Consisting of Reinforced Baked Clay”, pp.35-43in Proceedings of 7th International Civil Engineering Congress (ICEC-2015) “Sustainable Development through Advancements in Civil Engineering”, ed. F. Arif, U. Gazder, S. H. Lodi, -13, Karachi, Pakistan, 2015. 12 June.

- Elaborate for ore reserves of deposit “Crvena Mogila”- Delcevo, GRO Granit – Skopje 1982.

- Main mining design for surface exploitation of hard clay from deposit “Crvena Mogila” – Delcevo, Mining design bureau “Rudproekt”, Skopje 1989.

- A. Shubbar et al. (2019): “Future of clay-based construction materials – A review”, Constr Build Mater, 210 (2019) 172–187.

- N. B. Singh, “Clays and Clay Minerals in the Construction Industry”, Minerals, 12, 2022.

- J. J. Kipsanai et al., “A Review on the Incorporation of Diatomaceous Earth as a Geopolymer-Based Concrete Building Resource”, Materials Science Forum 15 (2022) 645-650.

- M. Jovanovski, “Elaborate on detailed geological investigations on solid clay at the locality Crvena Mogila in Delchevo”, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Skopje, 2011.

- MKS EN 1926: Natural stone test methods - Determination of uniaxial compressive strength.

- MKS EN 12371: Natural stone test methods - Determination of frost resistance.

- MKS EN 1925: Natural stone test methods - Determination of water absorption coefficient by capillarity.

- MKS EN 13755: Natural stone test methods - Determination of water absorption at atmospheric pressure.

- MKS EN 1936: Natural stone test methods - Determination of real density and apparent density, and of total and open porosity.

- MKS EN 772-1: Methods of test for masonry units Part 1: Determination of compressive strength.

- MKS EN771-1: Specification for masonry units - Part 1: Clay masonry units.

- MKS EN 772-21: Methods of test for masonry units - Part 21: Determination of water absorption of clay and calcium silicate masonry units by cold water absorption.

- EN 772-3: Methods of test for masonry units - Part 3: Determination of net volume and percentage of voids of clay masonry units by hydrostatic weighing.

- MKS ISO 8301: Thermal insulation — Determination of steady-state thermal resistance and related properties — Heat flow meter apparatus.

- MKS EN 12667:2009: Thermal performance of building materials and products — Determination of thermal resistance by means of guarded hot plate and heat flow meter methods — Products of high and medium thermal resistance.

| Parameters | Results |

|---|---|

| Chloride content () | 0,17 % |

| Contents of sulfates () soluble in acid | 0,74 % |

| Organic substances | none |

| Sample | Dimensions [cm] |

mass [g] |

Volume [cm3] |

Density [kg/m3] |

Force [kN] |

Compressive strength [MPa] | Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | b | h | m | V | γ | F | |||

| 1 | 5,19 | 5,10 | 5,18 | 188,10 | 137,11 | 1371,90 | 79,00 | 29,85 | Dry |

| 2 | 5,10 | 5,25 | 5,21 | 197,80 | 139,50 | 1417,94 | 102,60 | 38,32 | |

| Average value | 5,15 | 5,18 | 5,20 | 192,95 | 138,30 | 1394,92 | 90,80 | 34,08 | |

| 3 | 5,11 | 5,26 | 5,23 | 209,60 | 140,58 | 1491,02 | 93,80 | 34,90 | Saturated |

| 4 | 4,98 | 5,05 | 5,05 | 146,60 | 127,00 | 1154,31 | 20,10 | 7,99 | |

| Average value | 5,05 | 5,16 | 5,14 | 178,10 | 133,79 | 1322,66 | 56,95 | 21,45 | |

| 5 | 5,05 | 4,96 | 5,02 | 149,90 | 125,74 | 1192,13 | 46,20 | 18,44 | Frost |

| 6 | 5,19 | 5,21 | 5,11 | 202,90 | 138,17 | 1468,44 | 57,40 | 21,23 | |

| Average value | 5,12 | 5,09 | 5,07 | 176,40 | 131,96 | 1330,29 | 51,80 | 19,84 | |

| 1. | Real density | MKS EN 1936 | 1390 | ||

| 2. | Apparent density | 2630 | |||

| 3. | Total porosity | % | 52,85 | ||

| 4. | Open porosity | % | 47,15 |

| Ingredient | Cement | Water | w/c | additive | Aggregate dmax = 8 mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fine red solid clay aggregate (fraction 0-4 mm) |

Fine aggregate (fraction 0-4 mm) |

Fine aggregate (fraction 4-8 mm) |

|||||

| Quantity | 300 kg | 100 kg | 0,33 | / | 900 kg (50%) | 400 kg (22%) | 500 kg (28%) |

| Specimen | Compressive strength | Dry mass mdry,u | Mass after soaking | Gross volume Vg,u | Net volume Vn,u | Gross dry density | Net dry density | Water absorption | Percentage of pores and voids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [MPa] | [g] | [g] | [104mm3] | [104mm3] | [kg/m3] | [kg/m3] | [%] | [%] | |

| I – 1 | 3,00 | 13178 | 15114 | 1397 | 812 | 943 | 1622 | 14,69 | 44,48 |

| I – 2 | 3,26 | 13389 | 15322 | 1381 | 808 | 970 | 1658 | 14,44 | 43,12 |

| Average block I | 3,1 | - | - | - | - | 956 | 1640 | 14,56 | 44 |

| II – 1 | 3,93 | 12466 | 15114 | 1390 | 603 | 897 | 1601 | 21,24 | 45,70 |

| II – 2 | 4,32 | 12796 | 15322 | 1393 | 623 | 919 | 1600 | 19,74 | 44,86 |

| Average block II | 4,1 | - | - | - | - | 908 | 1601 | 20,49 | 45,28 |

| Properties | Material | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite block with red solid clay (tested results) | Ordinary concrete block | Autoclaved lightweight concrete block | |

| Percentage of pores and voids [%] | 44,00% - 45,28% | 18,50% - 26,40% | 60,00% – 80,00% |

| Degree of water absorption [%] | 14,56% - 20,49% | 4,40% - 7,55% | 40,00% - 80,00% |

| Thermal conductivity λ [W/m∙K] | 0,337 | 2,3 | 0,14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).