1. Introduction

Worldwide, intertrochanteric fractures account for roughly half of the 6–7 million hip fractures projected annually by 2050. Most occur in adults aged ≥65 years and are associated with 30-day and 1-year mortality rates of 10% and 20%–30%, respectively [

1]. Recent Japanese epidemiological data demonstrate a persistent rise in proximal femoral fractures, with 2005–2014 surveillance documenting a steadily increasing incidence [

2]. A 35-year prefectural cohort study further reported 3,369 hip fractures in 2020 alongside a pronounced rebound in individuals aged ≥90 years [

3]. The resulting loss of independent mobility increases institutional care demand and generates direct medical costs exceeding USD 20 billion annually in high-income countries [

4]. A more recent European report presents that fragility fractures in the EU27+2 region incurred direct healthcare costs of €56.9 billion in 2019—an increase of approximately USD 2,000–5,000 per case compared with earlier estimates [

5].

Failed cephalomedullary fixation—particularly lag-screw or helical-blade cutout—remains the most devastating mechanical complication, requiring revision arthroplasty in up to 7% of cases [

6]. In a recent multicenter nested case–control study (n = 2,327), Inui et al. reported that anterior malreduction—defined as anterior displacement of the distal fragment on postoperative oblique-lateral radiographs—increased the risk of cutout independently of the tip–apex distance [

7]. Although the tip–apex distance has been a well-established predictor of cutout, their findings shed new light on the independent effect of anterior malreduction, emphasizing its clinical relevance.

Despite apparently acceptable intraoperative images, clinicians continue to observe anterior redisplacement on early follow-up radiographs [

8]. This phenomenon indicates that static malreduction explains only part of the failure mechanism; fracture segments may move secondarily through lag-screw telescoping or posterior sagging before the cortical buttress engages [

9,

10]. However, the incidence, predictors, and clinical consequences of this dynamic instability have not been quantified in a large cohort.

Therefore, a 12-year retrospective cohort study of 598 geriatric trochanteric fractures treated with cephalomedullary nails was undertaken to (i) determine the incidence of postoperative anterior redisplacement, (ii) identify preoperative and postoperative risk factors, and (iii) clarify its relationship to implant failure.

We hypothesized that fractures initially presenting with an anterior alignment—or reduced to a neutral (anatomical) rather than posterior-buttress position—would exhibit higher rates of anterior redisplacement and, consequently, greater mechanical instability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fukuyama City Hospital (Approval number 846 dated 29 November 2024). The requirement for informed consent was managed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board. Where applicable, patients were provided the opportunity to opt out, and all data were anonymized by removing personal identifiers prior to analysis to ensure patient confidentiality. Data were securely stored in an encrypted hospital database, accessible only to authorized researchers.

2.2. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

This single-center, retrospective cohort study enrolled consecutive patients aged ≥65 years who underwent intramedullary nail fixation for trochanteric femoral fractures at our institution between January 2012 and December 2023.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pathological fractures, (2) lack of postoperative oblique-lateral radiographs, and (3) loss to follow-up before the first postoperative radiograph was taken. After exclusion, 598 hips of 577 patients constituted the final study cohort. Twenty-one patients sustained metachronous contralateral fractures—i.e., the second hip fracture occurred at a different time and required a separate admission. Each patient contributed two hips, which were analyzed as independent observations because the study focused on hip-specific factors. To analyze anterior redisplacement, we stratified the data by postoperative reduction subtype. As anterior redisplacement was defined as a shift from a posterior or anatomical to an anterior position, hips that were already in an anterior position postoperatively were not eligible for this analysis.

2.3. Radiographic Classification

Standard anteroposterior and oblique-lateral radiographs of the hip were obtained before surgery, immediately after surgery, at 1 week after surgery, and at routine follow-up visits as determined by the treating physician.

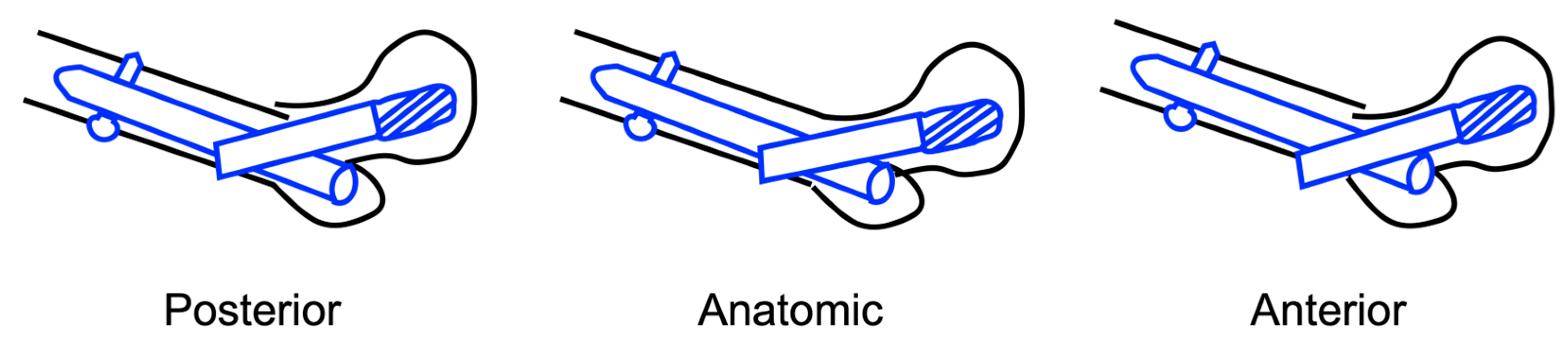

Sagittal reduction on the oblique-lateral radiographic view was classified into three subtypes (

Figure 1):

Posterior: the distal fragment lies posterior to the proximal fragment.

Anatomical: the cortices of the two fragments are co-linear.

Anterior: the anterior cortex of the distal fragment lies anterior to the anterior cortex of the proximal fragment.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was anterior redisplacement, defined as the postoperative migration of a distal fracture segment that had been reduced in an anatomical or posterior position to an anterior position on any follow-up radiograph. The secondary outcome was lag-screw cutout; however, no cutout events occurred during follow-up; therefore, this endpoint is described but not formally analyzed.

2.5. Covariates

The following potential confounders were extracted from the medical records and radiographs: age, sex, comorbidities, Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association (AO/OTA) classification (31A1/A2/A3) [

12], Jensen classification (I–V) [

13], nail length (short, <230 mm; middle, 230–260 mm; and long >260 mm), canal-filling ratio (defined as the ratio of the nail diameter to the canal diameter measured on both anteroposterior and oblique-lateral radiographs—at 1 cm proximal to the nail tip for short nails and at the narrowest point of the canal for middle and long nails), and the preoperative sagittal subtype described above.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and were compared through Student’s t-test or Welch’s t-test, depending on the equality of variances. Categorical variables, which were compared by Fisher’s exact test, are reported as counts with percentages. Variables associated with anterior redisplacement in the univariate analysis (p <0.05) were simultaneously entered into a multivariate logistic regression model. Results are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Model calibration was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using EZR (Easy R) version 2.73 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

During the study period, a total of 598 hips (mean age, 85.6 ± 7.6 years; 444 women and 154 men) underwent intramedullary nail fixation for trochanteric femoral fractures. Baseline comorbidities included cardiovascular disease in 197 hips, renal disease in 96, pulmonary disease in 65, cerebrovascular disease in 123, and dementia in 151 (

Table 1).

Various cephalomedullary nails were used, such as InterTAN® (n = 302; Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA), IPT® (n = 112; HOMS, Tokyo, Japan), PFNA® (n = 109; DePuy Synthes, Zuchwil, Switzerland), and others. Details of all implant types and manufacturers are provided in

Table S1.

The subtypes of the preoperative sagittal alignment were posterior in 109 hips (18.2%), anatomical in 151 (25.2%), and anterior in 338 (56.5%).

3.2. Incidence of Anterior Redisplacement

Among all 598 fractures, 204 (34.1%), 339 (56.7%), and 55 (9.1%) were reduced to a posterior, anatomical, and anterior positions, respectively on postoperative radiograph. Given that fractures that had already reduced anteriorly could not translate further anteriorly, these 55 hips were excluded, leaving 543 evaluable hips for the redisplacement analysis.

Among the 543 hips analyzed, posterior reduction was achieved significantly more often in female patients, in fractures classified as more complex by the AO and Jensen systems, and in cases treated with middle or long intramedullary nails (

Table 2).

Overall, anterior redisplacement occurred in 73 of 543 (13.4%) hips. No significant associations were found between anterior redisplacement and age, sex, AO/OTA, Jensen classification, nail length, and filling ratio (all p > 0.05;

Table 3).

Preoperative sagittal alignment influenced the risk of redisplacement (

Figure 2,

Table 4a). The incidence rates were 6.2% (6/97), 8.5% (12/141), and 18.0% (55/305) in patients with preoperative posterior, anatomical, and anterior subtypes, respectively (overall, p = 0.0005; pairwise p < 0.01 for posterior vs anterior and anatomical vs anterior).

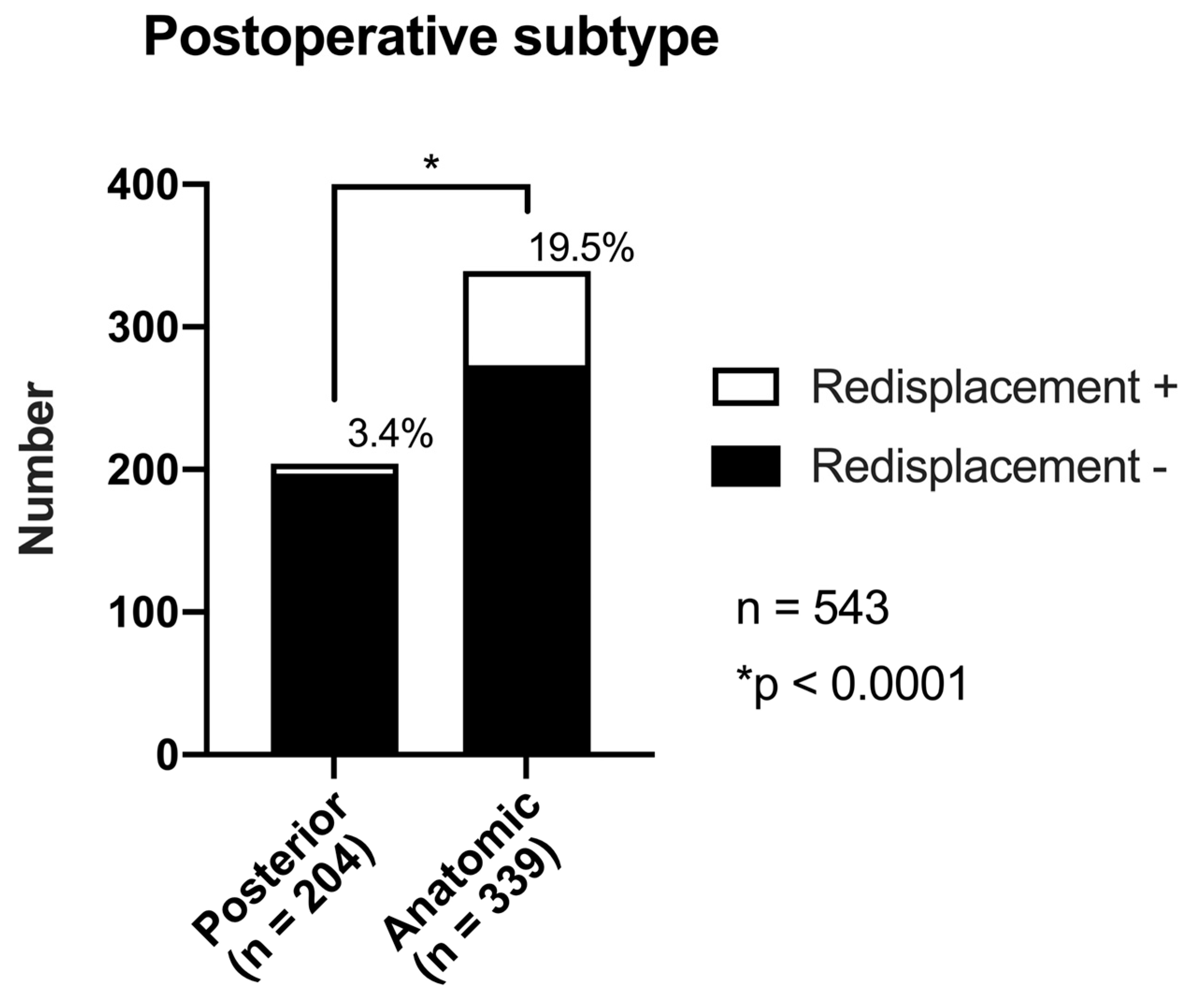

Postoperative sagittal reduction showed a strong association with anterior redisplacement (

Figure 3,

Table 4b). Anterior redisplacement was significantly more frequent in anatomical reduction than in posteriorly reduced hips (19.5% [66/339] vs 3.4% [7/204]; p <0.001).

The white portions of the bars represent cases with anterior redisplacement, whereas the black portions represent cases without redisplacement. The percentage above each bar indicates the incidence of redisplacement in that group: 6.2%, 8.5%, and 18.0% in the posteriorly, anatomically, and anteriorly aligned groups, respectively. The overall comparison across subtypes was significant (*p = 0.0016, Fisher’s exact test). Total number of cases, n = 543

Table 4.

a. Incidence of anterior redisplacement according to the preoperative alignment subtype.

Table 4.

a. Incidence of anterior redisplacement according to the preoperative alignment subtype.

| Preoperative subtype |

Anterior translation (+) |

Anterior translation (–) |

Total |

Incidence

(%) |

p-value |

| Posterior |

6 |

91 |

97 |

6.2% |

NA |

| Anatomical |

12 |

129 |

141 |

8.5% |

NA |

| Anterior |

55 |

250 |

305 |

18.0% |

<0.01 |

| Total |

73 |

470 |

543 |

13.4% |

|

Incidence of anterior redisplacement according to the postoperative reduction subtype. The anatomically reduced group exhibited a significantly higher incidence of redisplacement (19.5%) than the posteriorly reduced group (3.4%) (p < 0.0001).

Table 4.

b. Incidence of anterior redisplacement according to the postoperative reduction subtype.

Table 4.

b. Incidence of anterior redisplacement according to the postoperative reduction subtype.

| Postoperative subtype |

Anterior translation (+) |

Anterior translation (–) |

Total |

Incidence

(%) |

p-value |

| Posterior |

7 |

197 |

204 |

3.4% |

< 0.01 |

| Anatomical |

66 |

273 |

339 |

19.5% |

NA |

| Total |

73 |

470 |

543 |

13.4% |

|

The incidence was significantly higher in the anatomically reduced group (19.5%) than in the posteriorly reduced group (3.4%). Cases with the postoperative anterior subtype (n = 55) were excluded from this analysis.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate logistic regression identified two independent risk factors for anterior redisplacement (

Table 5): preoperative anterior position (vs non-anterior) with an OR of 1.87 (95% CI 1.24–2.81, p = 0.003) and postoperative anatomical reduction (vs posterior) with an OR 6.49 (95% CI 2.92–14.44, p <0.001). The model showed acceptable calibration (Hosmer–Lemeshow, χ² = 7.265, p = 0.123), with a Nagelkerke R² of 0.134, and correctly classified 86.5% of the cases.

Reference categories: preoperative position = non-anterior (anatomical/posterior); postoperative reduction = posterior reduction.

In the multivariate logistic regression (

Table 5), both preoperative anterior position and postoperative anatomical reduction were independent predictors of anterior redisplacement. Specifically, a preoperative anterior position was associated with a 1.87-fold increase in the odds of redisplacement (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.24–2.81; p = 0.003), and anatomical postoperative reduction conferred a 6.49-fold higher OR than posterior reduction (OR 6.49, 95% CI 2.92–14.44; p <0.001).

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

In this large, single-center cohort of 598 hips from older patients who underwent intramedullary nailing for the treatment of trochanteric femoral fractures, anterior redisplacement occurred in 13.4% of the 543 hips that had been reduced in either an anatomical or posterior position. Multivariate analysis identified two independent and clinically actionable risk factors: a preoperative anterior fracture alignment almost doubled the odds of redisplacement (OR 1.87), and a postoperative anatomical reduction increased the odds more than sixfold compared with posterior reduction (OR 6.49) (

Table 5). Neither fracture morphology (AO/OTA and Jensen classification) nor implant-related variables (nail length and filling ratio) were associated with redisplacement (

Table 3).

Taken together, these

findings indicate that sagittal alignment—particularly the surgeon-controlled achievement of a slight posterior reduction—outweighs implant choice and fracture complexity as the dominant, modifiable determinant of postoperative stability.

Compared with hips reduced to an anatomical position, posterior reduction on postoperative radiographs was more frequently observed in female patients, in those with more complex fracture patterns, and in those treated using middle or long nails (

Table 2). These patterns largely reflect the surgeon’s preference: posterior alignment was deliberately selected for female patients with osteoporosis and those with unstable fractures. This selection bias may have influenced the final outcomes because posterior reduction was more likely achieved in cases where postoperative redisplacement was already of concern.

4.2. Pathophysiological Interpretation

Postoperative anterior redisplacement occurs when the distal shaft fragment does not lie posterior to the head–neck fragment, leaving the anteromedial cortex unsupported. Under axial loading, this produces a sagittal-swing moment that drives the proximal fragment further into flexion. Once the lag-screw telescopes, secondary sliding amplifies the displacement and shortens the neck [8, 11, 14]. In contrast, placing the head–neck fragment slightly posterior (≤1 cortical thickness) to the shaft establishes an anteromedial buttress that converts shear into compression and allows sharing of loads between the bone and the nail. Biomechanical tests have shown that compared with an intramedullary (anterior) reduction, this “extramedullary” or “positive medial cortical support” configuration halves telescoping and reduces nail migration [15, 16]. In the present cohort, such posterior over-reduction lowered the odds of redisplacement sixfold (OR 6.49).

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the relationship between preoperative displacement and postoperative loss of reduction. Patients presenting with anterior shift of the distal segment preoperatively were more likely to experience postoperative redisplacement, even when anatomical or posterior reduction was achieved (

Table 4a,

Table S2). This finding may suggest an inherent instability in fracture patterns that initially present with anterior displacement.

4.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

Most studies have focused on coronal alignment and the tip–apex distance, with relatively few large-scale analyses of sagittal reduction and postoperative redisplacement [

7,

17]. Biomechanical and small clinical reports have shown that anterior malreduction increases the risk of lag-screw cutout and implant sliding, whereas positive medial cortical support limits impaction and pain [

8,

14,

15]. Although no cutout events occurred in the study cohort and functional outcomes were not assessed systematically, these data collectively suggest that avoiding anterior redisplacement remains a prudent surgical objective.

More recent series have identified dynamic risk factors for redisplacement—comminution at the greater trochanter and low lateral canal-filling ratio [

18]—however, in our cohort, the filling ratio was not predictive, and Jensen type Ⅲ–Ⅴ fractures did not exhibit greater instability (

Table 3). This highlights the primacy of anteromedial buttress over fracture morphology. However, posterior reduction was more often applied in cases with presumed greater instability, which may have influenced these results (

Table 2).

Several recent studies have employed three-dimensional computed tomography to characterize sagittal fragment alignment and cortical buttress formation more precisely [

9,

18,

19], an approach not employed in the present radiograph-based analysis.

By modeling both preoperative and postoperative sagittal alignment within a single logistic framework in the largest uniform radiograph-based cohort to date (n = 598), this study clarified their independent and additive contributions to postoperative stability (

Table 5). This study extends this literature in three ways by (i) evaluating dynamic redisplacement rather than static malreduction, capturing fractures that were acceptable intraoperatively but destabilized during early loading; (ii) modeling preoperative and postoperative alignment within the same logistic framework, clarifying their independent and additive contributions to instability; and (iii) analyzing the largest single-institution cohort to date (n = 598) with uniform imaging and follow-up, thereby narrowing the CIs around the effect estimates. Importantly, the fact that Jensen type Ⅲ–V fractures did not exhibit higher redisplacement rates (

Table 3) underscores the critical importance of support at the thick anteromedial cortex, irrespective of posterior comminution.

4.4. Clinical Implications: Why A Deliberate Posterior Reduction Deserves Routine Consideration

The present findings, together with converging biomechanical and clinical evidence [

7,

11,

14,

20], challenge the traditional goal of an anatomically flush sagittal cortex and support a controlled posterior offset. Leaving the head–neck fragment slightly posterior to the shaft (≤1 cortical thickness) (i) transforms shear into compressive loading across the buttress, (ii) limits telescoping to < 2 mm, thus preventing the 5–10 mm of uncontrolled shortening often seen after “anatomical” reductions, and (iii) mitigates varus drift and lag-screw cutout risk. Importantly, this target position is straightforward to visualize intraoperatively: a 30° oblique-lateral radiographic view should show the distal anteromedial cortex overlapping the proximal spike [

21]. When closed manipulation yields a flush or anterior cortex, surgeons should favor a deliberate posterior over-reduction—achievable with a small anteriorly directed elevator—rather than additional traction or nail exchange. Incorporating an item such as “anteromedial cortical buttress achieved (yes/no)” into intraoperative checklists, alongside the tip–apex distance and neck–shaft angle, may facilitate the consistent adoption of this technique.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

The strengths are related to the study being the largest single-center series to date, use of uniform surgical technique, blinded radiographic adjudication, and multivariable modeling that separates preoperative and postoperative alignment.

Limitations are intrinsic to the study design:

1. Single-institution, retrospective cohort: practice patterns may differ elsewhere; selection and information bias cannot be fully excluded.

2. Follow-up heterogeneity: although 92% of patients had ≥3 months of imaging data, late attrition may underestimate very delayed redisplacement.

3. Unmeasured confounders: bone density, surgeon experience, and rehabilitation protocols were not captured; each could influence stability.

These caveats tamper the generalizability of our numeric risk estimates, but not the biomechanical principle that the anteromedial buttress matters.

4. Clinical outcomes: the study could not evaluate functional or symptomatic outcomes. Although cutout was initially considered a secondary endpoint, no such cases were observed during follow-up. In addition, postoperative lag-screw telescoping and pain were not assessed.

4.6. Future Directions

Prospective, multicenter trials should examine deliberate posterior-biased reduction versus anatomical reduction with standardized implants, rehabilitation, and longer (>12 months) follow-up. Embedding intraoperative motion analysis—for example, optical tracking of fragment drift between reduction and wound closure—could identify micro-instability invisible on two-dimensional fluoroscopy. Finally, finite-element and cadaver models integrating patient-specific bone density may clarify how much posterior offset is optimal for different fracture patterns.

5. Conclusions

Preoperative anterior fracture alignment and postoperative anatomical reduction are independent, clinically significant risk factors for anterior redisplacement following intramedullary nailing of trochanteric femoral fractures in older patients. Achieving—or deliberately leaving—a slight posterior reduction offers a simple, readily modifiable strategy to mitigate this complication and may translate into better functional outcomes and fewer implant failures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Cephalomedullary nail implants used in the study population: device names, manufacturers, and number of cases and Table S2: Preoperative and postoperative subtypes with the number and percentage of anterior redisplacement cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K., S.Y. and C.T.; methodology, H.K., S.Y. and C.T.; software, H.K. and S.Y. ; validation, H.K; formal analysis, H.K. and S.Y.; investigation, H.K.; data curation, H.K. and S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K. and S.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.K., S.Y., Y.O., J.K., K.S., T.I., K.Y. and C.T.; visualization, H.K. and S.Y.; supervision, S.Y. ,Y.O., K.Y. and C.T.; project administration, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fukuyama City Hospital (Approval number 846 dated 29 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was managed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board. Where applicable, patients were provided the opportunity to opt out, and all data were anonymized by removing personal identifiers prior to analysis to ensure patient confidentiality.

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical considerations, we are unable to make the full dataset publicly available. However, we are open to discussing requests for anonymized data from qualified researchers under appropriate agreements.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge our institution for their contributions to the study, including support with patient data collection and surgical expertise.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, K.; Kang, H.; Ye, D.; Li, F. What was the Epidemiology and Global Burden of Disease of Hip Fractures From 1990 to 2019? Results From and Additional Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2023, 481, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, A.; Gao, Z.; Arai, K.; Yoshimura, N. 30-year trends of hip and vertebral fracture incidence in Japan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Metab 2022, 40, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozaki, A.; Imai, N.; Shobugawa, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Horigome, Y.; Endo, N.; Kawashima, H. Increased incidence among the very elderly in the 2020 Niigata Prefecture Osteoporotic Hip Fracture Study. J Bone Miner Metab 2023, 41, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernlund, E.; Svedbom, A.; Ivergard, M.; Compston, J.; Cooper, C.; Stenmark, J.; McCloskey, E.V.; Jonsson, B.; Kanis, J.A. Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. This report was prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 2013, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanis, J.A.; Norton, N.; Harvey, N.C.; Jacobson, T.; Johansson, H.; Lorentzon, M.; McCloskey, E.V.; Willers, C.; Borgstrom, F. SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos 2021, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chang, S.M.; Niu, W.X.; Ma, H. Comparison of tip apex distance and cut-out complications between helical blades and lag screws in intertrochanteric fractures among the elderly: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sci 2015, 20, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Inui, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Matsui, K.; Kurata, Y.; Ishii, K.; Kurozumi, T.; Kawano, H. Anterior Malreduction is Associated With Lag Screw Cutout after the Internal Fixation of Intertrochanteric Fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2024, 482, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukada, S.; Okumura, G.; Matsueda, M. Post-operative stability on lateral radiographs in the surgical treatment of pertrochanteric hip fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012, 132, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.M.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Du, S.C.; Ma, Z.; Hu, S.J.; Yao, X.Z.; Xiong, W.F. Anteromedial cortical support reduction in unstable pertrochanteric fractures: a comparison of intraoperative fluoroscopy and postoperative three-dimensional computerised tomography reconstruction. Int Orthop 2018, 42, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Kang, M.S.; Lim, E.J.; Park, M.L.; Kim, J.J. Posterior Sagging After Cephalomedullary Nailing for Intertrochanteric Femur Fracture is Associated with the Separation of the Greater Trochanter. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2020, 11, 2151459320946013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozono, N.; Ikemura, S.; Yamashita, A.; Harada, T.; Watanabe, T.; Shirasawa, K. Direct reduction may need to be considered to avoid postoperative subtype P in patients with an unstable trochanteric fracture: a retrospective study using a multivariate analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014, 134, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinberg EG, Agel J, Roberts CS, Karam MD, Kellam JF. Fracture and Dislocation Classification Compendium—2018. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(Suppl 1):S1-S170. [CrossRef]

- Jensen JS. Classification of Trochanteric Fractures. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51(5):803-810. [CrossRef]

- Momii, K.; Fujiwara, T.; Mae, T.; Tokunaga, M.; Iwasaki, T.; Shiomoto, K.; Kubota, K.; Onizuka, T.; Miura, T.; Hamada, T.; et al. Risk factors for excessive postoperative sliding of femoral trochanteric fracture in elderly patients: A retrospective multicenter study. Injury 2021, 52, 3369–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.M.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Ma, Z.; Li, Q.; Dargel, J.; Eysel, P. Fracture reduction with positive medial cortical support: a key element in stability reconstruction for unstable pertrochanteric hip fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015, 135, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, T.; Minehara, H.; Tazawa, R.; Matsuura, T.; Sakai, R.; Takaso, M. Biomechanical Evaluation of Extramedullary Versus Intramedullary Reduction in Unstable Femoral Trochanteric Fractures. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2021, 12, 2151459321998611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murena, L.; Moretti, A.; Meo, F.; Saggioro, E.; Barbati, G.; Ratti, C.; Canton, G. Predictors of cut-out after cephalomedullary nail fixation of pertrochanteric fractures: a retrospective study of 813 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018, 138, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furui, A.; Terada, N.; Mito, K. Mechanical simulation study of postoperative displacement of trochanteric fractures using the finite element method. J Orthop Surg Res 2018, 13, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Chang, S.M.; Hu, S.J.; Du, S.C. A low filling ratio of the distal nail segment to the medullary canal is a risk factor for the loss of anteromedial cortical support: a case control study. J Orthop Surg Res 2022, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Yokoo, S.; Demiya, K.; Inoue, M.; Noda, T.; Ozaki, T.; Yorifuji, T. Association between Immediate Postoperative Radiographic Findings and Failed Internal Fixation for Trochanteric Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.Y.; Chang, S.M.; Tuladhar, R.; Wei, Z.; Xiong, W.F.; Hu, S.J.; Du, S.C. A new fluoroscopic view for evaluation of anteromedial cortex reduction quality during cephalomedullary nailing for intertrochanteric femur fractures: the 30 degrees oblique tangential projection. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2020, 21, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).