1. Introduction

The incidence of liver disease is increasing globally [

1]. It is the second most common cause of premature deaths in the Europe, America, and Africa, and the third most in South-East Asia [

2]. Over time, chronic liver disease can lead to liver cirrhosis and liver failure. At present, the only cure for end-stage liver failure is liver transplantation, however, the patient demand far exceeds donor supply. In the United Kingdom alone, patients wait an average of 3 to 4 months for a liver transplant for chronic liver failure [

3]. Unfortunately, approximately 10% of these patients die on the waiting list due to complications of their liver disease, and even a greater number are turned down for transplantation [

4,

5]. Therefore, novel therapies for the treatment of liver failure are urgently needed.

Bioengineering liver tissue from human stem cells and organoids offers excellent potential as an alternative to conventional liver transplantation. Vast quantities of cells and/or tissue could be generated in vitro, relieving the strain on the limited donor pool. In addition, hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, or liver organoids derived from patient-specific stem cells enable the autologous transplantation of end-target cells or tissue, thereby negating the need for long-term immune suppression and its associated side effects, which are often encountered with non-autologous liver transplantation. For example, Japanese researchers have successfully transplanted hepatocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells into an infant with urea cycle disorder, temporarily reversing the disease so that a liver transplant could be performed safely five months later [

6]. Apart from cell therapy or tissue transplantation, regenerative approaches can also be used for disease modelling and predicting response to novel drug therapies more accurately [

7,

8,

9]. It is noteworthy that approximately half of the drugs that have caused drug-induced liver injury in humans did not have any significant liver-toxic effects in animal testing [

10]. In contrast, stem cell-derived liver models, such as bioengineered liver tissue or liver-on-a-chip devices, have demonstrated good concordance between in vitro and in vivo drug toxicity, making them of strong interest to the pharmaceutical industry [

11].

Despite the immense potential of stem cell-derived liver cells and tissue, it is widely recognised that current culture conditions are sub-optimal and yield immature end-target cells compared to primary cells [

12,

13]. A key factor attributed to this shortcoming is the lack of suitable biomaterials that accurately reproduce the stem cell niche during liver differentiation, both in terms of composition and dimensionality [

14,

15]. Three-dimensional (3D) systems and tissue-specific matrices yield better cellular phenotypes than two-dimensional (2D) culture systems and generic substrates, respectively [

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, substrates commonly used in 3D culture systems, like Matrigel, are usually xenogenic and associated with many problems. For example, growth factors such as epidermal growth factor, insulin growth factor-1 and fibroblast growth factor 2 concentrations are inconsistent between Matrigel batches [

20,

21]. In addition, growth-factor-reduced versions of Matrigel contain only 53% of the extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins found in Matrigel [

22]. These inconsistencies cause significant biochemical and mechanical variations [

23], leading to poorly reproducible in vitro results [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Furthermore, poor definability, immunogenicity [

25,

26] and pathogenicity [

27,

28] preclude its use and any downstream products from clinical therapy [

29].

Therefore, novel and better biomaterials are urgently needed for clinical translation. The primary objective of this focused systematic review was to study the biomaterials used in liver bioengineering between 2020 and 2025, thereby understanding the direction of future practices. The secondary objective is to appraise novel biomaterials for their potential for clinical translation, focusing on definability, versatility, degradability, and biosafety. It is essential to note that different types of stem cells exhibit distinct responses to the various biopolymers within culture substrates and scaffolds based on their degree of stemness and inherent propensity to hepatic differentiation. Therefore, in the context of this review, we have classified the various types of stem cells broadly into three categories: (i) Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs), (ii) Liver Stem Cells (LSCs), and (iii) Non-Liver Stem Cells (NLSCs). PSCs refer to human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and embryonic stem cells (ESCs). LSCs refer to native human hepatic or biliary human progenitor stem cells, such as LGR5+ hepatoblasts. NLSCs refer to all other human non-pluripotent and non-liver stem cells, e.g., mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs).

Herein, we present a comprehensive summary of biomaterials usage within liver bioengineering, demonstrating that xenogenic matrices are still widely used. However, we have found that chemically defined alternatives are being increasingly explored, with recombinant human proteins gaining popularity as routine practice. Finally, we discuss the advantages and disadvantages of these alternatives and provide insights on the future direction of biomaterials research.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Summative Results of the Systematic Searches

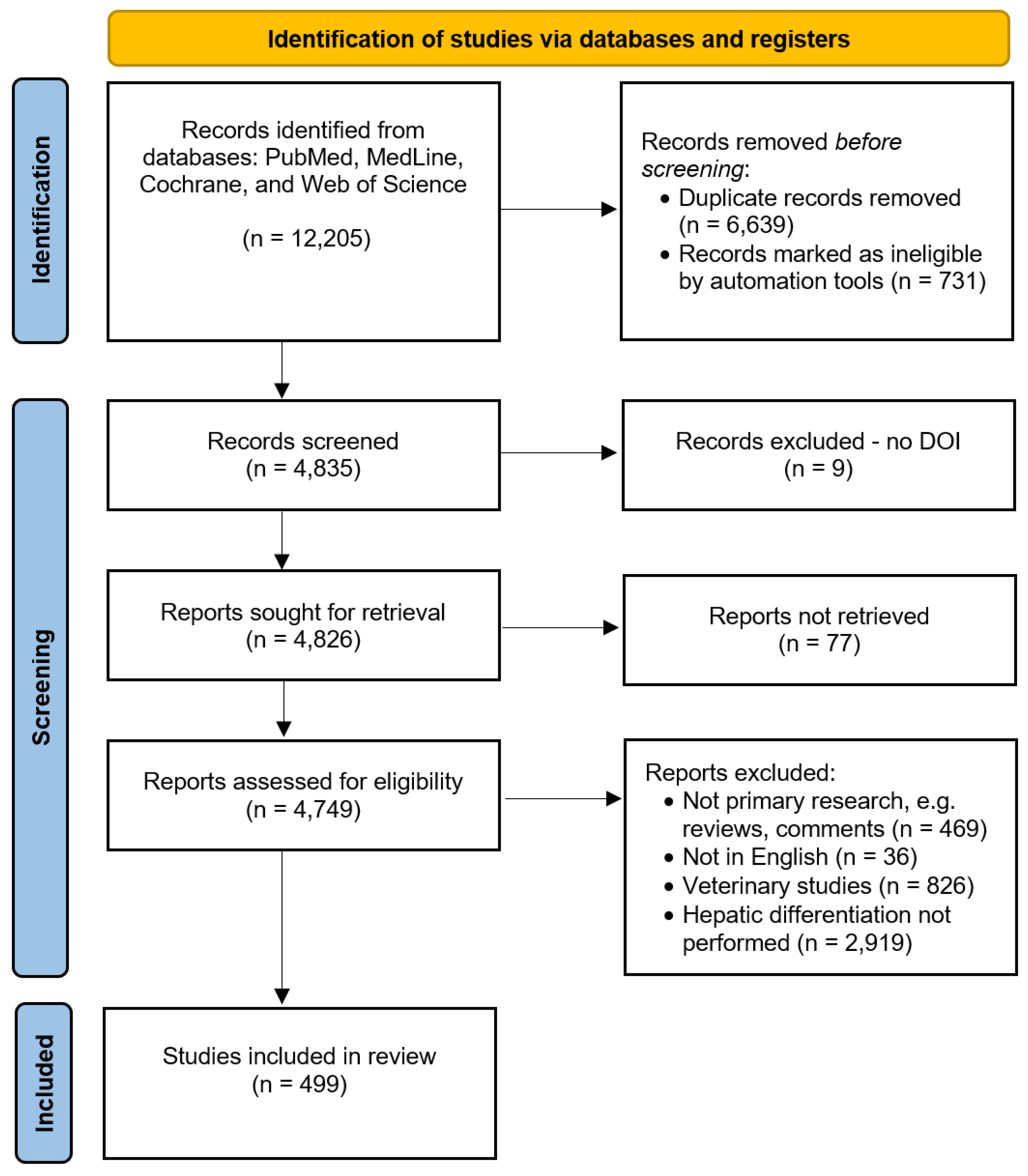

Four public databases were comprehensively searched for articles published between 1 April 2020 and 1 April 2025 that reported stem differentiation into liver cells, organoids, or tissue (the systematic search strategy is described in the Methods section). A total of 12,205 articles were identified. After removing duplicates and ineligible hits (n=7,370), 4,835 articles were screened for eligibility. During the screening process, 4,336 articles were excluded from further analyses, and 499 were included after meeting the inclusion criteria (see Methods section).

Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA systematic review flow diagram. Of these 499 articles, 282 used PSCs, 158 used LSCs, and 59 used NLSCs for liver bioengineering. The results of each stem cell group are reported separately below.

2.2. Biomaterials Used to Derive Liver Cells and Organoids from PSCs

Of the 282 studies that used PSCs (see Supplementary

Table 1), 8 reported cholangiocyte differentiation, 197 reported hepatocyte differentiation, 86 reported liver organoid culture, 1 reported differentiation of hepatic stellate cells, and 1 reported the differentiation of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC). 10 studies differentiated PSCs into hepatocytes AND cholangiocytes/liver organoids. 75.2% (212/282) of all these studies used Matrigel or its derivatives for maintenance or differentiation. The other types of biopolymers used are summarised in

Table 1.

100% (8/8) of PSC studies reporting cholangiocyte culture used Matrigel or its derivatives (growth factor-reduced Matrigel). 4 of 8 studies added Collagen-1 to Matrigel derivatives for cholangiocyte differentiation. Of the PSC studies reporting hepatocyte culture, 71.1% (140/197) used Matrigel or its derivatives, 13.7% (27/197) used Laminin 511 or its derivatives (Laminin 511-silk), and 10.7% (21/197) used Laminin 521 or its derivatives (Laminin 521-silk). The remaining studies used cellulose, Cellartis Definitive Endoderm Differentiation coating, Cellartis DEF-COAT 1, PEG-peptides, gelatin, fibronectin, liver scaffolds/ECM, HydroxTM coating (a peptide-functionalized hydrogel), Synthemax®® II coating (peptides covalently bonded to an acrylate polymer backbone), placental ECM, vitronectin, PAA, PLLA/PCL, PCL-Gel-HA, and suspension culture. For three-dimensional (3D) liver and/or organoid culture, 93.4% (71/86) used Matrigel or its derivatives. The remaining studies used Biomimesys®® (a hyaluronic acid-based scaffold that also contains collagen, laminin, and fibronectin), gelatin, GelMA, decellularised animal livers, Laminin 521, or PEG.

It is noteworthy that researchers have also used specific biopolymers that do not deliver chemical cues to PSCs. For example, agarose-based microfabricated hexagonal closely packed cavity arrays (mHCPCAs) have been explored as a suspension culture method [

31,

32]. The hypothesis is that the tightly controlled microenvironment created by mHCPCAs produces significantly less heterogeneity in organoid size, morphology, and maturation rate than standard Matrigel domes. Nonetheless, liver organoids produced by the mHCPCAs method are still noted to be immature [

31,

32]. Agarose is hydrophobic and lacks cell-binding motifs, which in turn promotes suspension culture, spheroid, or organoid formation [

33]. The lack of mechano- and chemical cues most likely explains these results and highlights the importance of bioactive biopolymers within scaffolds.

2.3. Biomaterials Used to Derive Liver Cells and Organoids from LSCs

Of the 158 studies that used LSCs (see Supplementary

Table 2), 3 reported cholangiocyte differentiation, 24 reported hepatocyte differentiation, 48 reported biliary organoid culture, and 89 reported liver organoid culture. 5 studies differentiated LSCs into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes/liver organoids. 76.4% (120/157) of all these studies used Matrigel or its derivatives for maintenance or differentiation. The other types of biopolymers used are summarised in

Table 2.

66.6% (2/3) of studies reporting cholangiocyte differentiation of LSCs used Matrigel or its derivatives (growth factor-reduced Matrigel); the remaining study used Collagen-1. Of the studies reporting hepatocyte differentiation from LSCs, 18.2% (4/22) used Matrigel or its derivatives. An identical proportion (4/22) used Collagen-1. 63.6% (14/22) of studies did not use any substrate, as LSC appear to be adherent cells in two-dimensional (2D) cell culture. In contrast, 93.9% (46/49) of studies used Matrigel or its derivatives for 3D biliary organoid culture; the remaining used collagen-1, hyaluronic acid or suspension culture. For 3D hepatic organoid culture, 85.4% (76/89) used Matrigel or its derivatives. The remaining studies used HydroxTM, Laminin 332, GelMA, PEG, PIC-Laminin 511, and suspension culture methods.

2.4. Biomaterials Used to Derive Liver Cells and Organoids from NLSCs

Of the 59 studies that used NLSCs (Supplementary

Table 3), 1 reported cholangiocyte differentiation, 52 reported hepatocyte differentiation, 1 reported liver sinusoidal endothelial cell culture, and 5 reported liver organoid culture. 3.4% (2/59) of all these studies used Matrigel or its derivatives for maintenance or differentiation. 18.6% (11/59) used Collagen-1 as a substrate. 55.9% (33/29) used no substrate. The other types of biopolymers used are summarised in

Table 3. Likewise,

The only study that reported cholangiocyte differentiation from NLSCs used collagen-1. Of the studies that reported hepatocyte differentiation, 63.5% (33/52) did not use any substrate, 23.1% (12/52) used collagen-1 or gelatin, and only one used Matrigel (growth factor reduced). Fibronectin was used for the only study that differentiated NLSCs into LSECs. For 3D liver organoid culture, Collagen-1 (2/5), Agarose (1/5), Lidipure coating (1/5) and Wharton’s Jelly (1/5) were used as substrates.

2.5. Discussion of Results

PSCs are the most attractive cell source for bioengineering liver tissue because of their potential to be differentiated into all other cell types in the human liver, e.g., HSCs, immune cells, LSECs, etc. However, the stemness of PSCs places greater importance on the biopolymers within the in vitro culture conditions because these become cues for directed differentiation and maturation towards the intended end-targets. In addition, the versatility of a substrate is crucial for its uptake in standard practice and clinical therapy. Ideal substrates should support the differentiation of stem cells into all cell types of the target organ, facilitate the different phases of differentiation without dissociation and replating cells for substrate changes. Substrates should also be easily transferable into humans, e.g., injectable or implantable. This study has identified several fully defined biomaterials used as an alternative to Matrigel-derived substrates in recent years. The properties of these biomaterials are briefly summarised in

Table 4.

Collagen-1 is frequently used in 2D hepatocyte and cholangiocyte differentiation. Nonetheless, it is widely recognised that on its own, it promotes undesired spontaneous differentiation of PSC and is sub-optimal for hepatic organoid culture. Thus, conjugation with other biomaterials is necessary; Matrigel can be added to Collagen-1 to support liver organoid culture (Supplementary

Table 1). The use of hyaluronic acid (HA) was featured in two studies: one study differentiated PSCs into hepatocytes using Biomimesys

®® - HA conjugated to Collagen-1 and Collagen-4 via RDG binding sites [

34]. The other study used HA conjugated with cholesterol and dexamethasone to maintain and differentiate LSCs into biliary organoids [

35]. Since HA is widely used in medicinal products, it is an interesting biomaterial for liver tissue engineering. However, further research is needed to determine if HA-based matrices can support the multi-cell type differentiation required in liver organogenesis, followed by validation with in vivo trials.

A total of four studies used fibronectin to maintain stem cells in culture [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Four studies used it for hepatocyte differentiation [

36,

38,

40,

41], and one study used it to derive LSECs [

39]. Indeed, fibronectin seems promising; however, in our experience, it is highly viscous, which makes it very challenging to use in cell culture. In addition, only two studies have reported results of short-term murine experiments. Therefore, more data, including animal studies, are needed. Fibroin is considered a bioactive material [

42]; however, it has only been used in one study with NLSCs [

43], so its potential is still undetermined.

Human recombinant laminins are a popular alternative to poorly defined xenogenic substrates, although Laminin types significantly affect stem cell biology. Laminin 511 and Laminin 521 are native to the developing embryo [

44], and are the only two Laminins that support the long-term clonal expansion of PSCs in vitro [

45]. Laminin 111 and Laminin 332 are associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [

46,

47], especially in ESCs [

46]. Therefore, on their own, they may not be suitable for long-term stem cell culture and/or differentiation, although the addition of either laminins to Laminin 511 or Laminin 521 may be a valuable strategy to achieve better end-target cells. Importantly, all available human recombinant laminins are only available in low-concentration aqueous solutions, which are unsuitable for 3D liver bioengineering. As a result, several groups have attempted to conjugate Laminins with various polymeric backbones to form hydrogels. Laminin 511-PIC [

48], PIC-LEC[

49], Laminin 511-Silk (Supplementary

Table 1 and

Table 2), and Laminin 521 (Biosilk) are recent attempts illustrated above. Nonetheless, robust in vivo data on these biomaterials are still outstanding. Notably, at the time of writing, only aqueous Laminin 511 (iMatrix) and Laminin 521 (Biolamina) are available in “good manufacturing grade”. Therefore, an essential strategy for 3D liver bioengineering would be to develop and refine clinical-grade hydrogels (or scaffolds) incorporating Laminin 511 or Laminin 521 with supportive ECMs to enhance end-target phenotypes. Notably, Laminin 411 has previously been reported to enhance liver differentiation [

50,

51,

52]. However, Laminin 411-containing scaffolds and substrates remain unexplored.

Our searches have also shown that synthetic alternatives such as PEG constructs have been increasingly explored. PEG is usually considered inert; thus, groups have conjugated PEG with bioactive polymers to deliver chemical cues to stem cells with some success. “HepMat” - PEG and RGD conjugates [

53], and other PEG-peptide constructs [

54] have been shown to support hepatocyte differentiation, but data on liver/biliary organoids culture and animal experimentation are still outstanding. Similarly, issues apply to most synthetic biomaterials listed in

Table 4. Synthetic polymers that have not been conjugated with other bioactive polymers were noted to be used as substrates to reduce cell adhesion and facilitate suspension culture, e.g., Lipidure, PLLA/PCL fibres, Hydrox fibres, etc. Nonetheless, undisclosed proprietary information and non-comprehensive methods significantly hinder the reproducibility and validation of novel synthetic materials.

In summary, approximately 75% of studies that bioengineer liver from PSCs and NLSCs continue to use Matrigel or its derivatives. NLSCs are self-adherent cells that do not require bioactive substrates for liver differentiation but are limited by their lack of pluripotency. Novel techniques to derive other liver cell types from NLSCs can significantly improve liver tissue engineering. Alternatively, hydrogels and scaffolds made from recombinant human proteins are attractive biomaterials to enhance liver derivation from PSCs and LSCS in future research.

3. Conclusions

Xenogenic substrates remain predominant biomaterials in liver bioengineering, although human recombinant proteins and synthetic alternatives are gaining popularity. Hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels are a promising alternative, but further research is needed. Laminin 511 and Laminin 521 are available as aqueous clinical-grade solutions only, and hydrogel development with in vivo validation is vital for future 3D liver bioengineering efforts and their clinical translation. Synthetic polymers are still underdeveloped and have more milestones to achieve than human recombinant matrices, which have been more extensively researched.

4. Materials and Methods

This review is reported in accordance with the recommendations from the PRISMA statement [

55].

4.1. Data Sources and Searches

Electronic searches: A search of PubMed, Medline, Cochrane and Web of Science databases was performed for articles in the last five years between 1 April 2020 to 1 April 2025 using the search terms “stem cells” and “hepatocytes”, “stem cells” and “cholangiocytes”, “liver” and “stem cells”, “liver organoids”, “hepatic organoids”, “biliary organoids”, and “cholangiocyte organoids”. The UK Access Management Federation provided access to journals via Cambridge University.

Searching in other resources: The Cambridge University Library was checked for articles that were listed in online search results but not accessible.

4.2. Study Selection

Inclusion criteria: Only (i) articles in English, (ii) articles with abstracts and full-text links for screening, and (iii) primary research articles were included.

Exclusion criteria: Articles (i) not reporting primary research (e.g., reviews, comments, etc.), (ii) not written in English, (iii) lacking a DOI, web-link, and not accessible by the UK Access Management Federation, were excluded. In addition, (iv) veterinary studies (e.g., animal cell lines and experimentation only) and (v) studies not reporting the differentiation of stem cells into liver cells, organoids, or tissue were also excluded.

4.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Selection of studies: Three authors (J.O., J.Z.Z. and C.S.) independently reviewed all titles and abstracts and then assessed articles against the inclusion criteria for analysis. A fourth reviewer (A.E.M.) resolved any differences.

Data extraction and management: Data were extracted independently by authors J.O., J.Z.Z. and C.S. using a standardised form. The data recorded included the biomaterials used, the stem cell type used, and the end-target cell or tissue type achieved.

Risk of bias and quality assessment. All primary research articles that fulfilled the above criteria were screened, minimising the risk of publication bias. The risk of language bias is present but low.

4.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

Statistical analysis: Articles that were successfully screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria had data extracted and tabulated in Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics were used to report data between the stem cell groups.

Dealing with missing data: Articles with missing data were omitted in the statistical analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity and publication bias: This was not applicable as meta-analyses were not performed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.O; methodology, J.O.; software, J.O.; validation, J.Z.Z, and C.S.; formal analysis, J.O., J.Z.Z, C.S.; investigation, J.O., J.Z.Z, C.S.; resources, J.O., J.Z.Z, C.S.; data curation, J.O., J.Z.Z, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.O.; writing—review and editing, J.O., J.Z.Z, C.S., A.E.M.; visualization, J.O.; supervision, A.E.M.; project administration, J.O.; funding acquisition, J.O. and A.E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the W.D. Armstrong Doctoral Fellowship, the School of Technology, University of Cambridge.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| 2D |

Two dimensional |

| 3D |

Three dimensional |

| DED |

Definitive Endoderm Differentiation |

| ESCs |

Embryonic Stem Cells |

| GelMA |

Gelatin Methacryloyl |

| GFR |

Growth Factor Reduced |

| HA |

Hyaluronic acid |

| iPSCs |

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| LIC-LEC |

PIC-Laminin 111-Entactin-Complex |

| LSCs |

Liver Stem Cells |

| LSECs |

Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells |

| MSCs |

Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| NLSCs |

Non-Liver Stem Cells |

| PSCs |

Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| PAA |

Polyacrylamide |

| PEG |

Polyethylene Glycol |

| PIC |

Polyisocyanopeptides |

| PLLA/PCL |

Poly-L-lactic acid/poly (ε-caprolactone) |

| PCL-Gel-HA |

Poly ɛ-caprolactone-gelatin-hyaluronic acid |

References

- Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. Journal of Hepatology. 2023 Aug 1;79(2):516–37. [CrossRef]

- Karlsen TH, Sheron N, Zelber-Sagi S, Carrieri P, Dusheiko G, Bugianesi E, et al. The EASL-Lancet Liver Commission: protecting the next generation of Europeans against liver disease complications and premature mortality. Lancet. 2022 Jan 1;399(10319):61–116. [CrossRef]

- Organ transplantation - NHS Blood and Transplant [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 4]. How long is the wait for a liver? Available from: https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/organ-transplantation/liver/receiving-a-liver/how-long-is-the-wait-for-a-liver/.

- Kim WR, Therneau TM, Benson JT, Kremers WK, Rosen CB, Gores GJ, et al. Deaths on the liver transplant waiting list: an analysis of competing risks. Hepatology. 2006 Feb;43(2):345–51. [CrossRef]

- Fink MA, Berry SR, Gow PJ, Angus PW, Wang BZ, Muralidharan V, et al. Risk factors for liver transplantation waiting list mortality. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Jan;22(1):119–24.

- The Government of Japan - JapanGov - [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 4]. ES Cells Give Small Lives a Chance for Tomorrow / The Government of Japan - JapanGov -. Available from: https://www.japan.go.jp/tomodachi/2020/summer2020/es_cells.html.

- Bengrine A, Brochot E, Louchet M, Herpe YE, Duverlie G. Modeling of HBV and HCV hepatitis with hepatocyte-like cells. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2016 Jan 1;8(1):97–105. [CrossRef]

- Holmgren G, Sjögren AK, Barragan I, Sabirsh A, Sartipy P, Synnergren J, et al. Long-term chronic toxicity testing using human pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2014 Sep;42(9):1401–6. [CrossRef]

- Takayama K, Morisaki Y, Kuno S, Nagamoto Y, Harada K, Furukawa N, et al. Prediction of interindividual differences in hepatic functions and drug sensitivity by using human iPS-derived hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Nov 25;111(47):16772–7. [CrossRef]

- Olson H, Betton G, Robinson D, Thomas K, Monro A, Kolaja G, et al. Concordance of the toxicity of pharmaceuticals in humans and in animals. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2000 Aug;32(1):56–67. [CrossRef]

- Underhill GH, Khetani SR. Bioengineered Liver Models for Drug Testing and Cell Differentiation Studies. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Dec 6;5(3):426-439.e1. [CrossRef]

- Messina A, Luce E, Benzoubir N, Pasqua M, Pereira U, Humbert L, et al. Evidence of Adult Features and Functions of Hepatocytes Differentiated from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Self-Organized as Organoids. Cells. 2022 Feb 4;11(3):537. [CrossRef]

- Harrison SP, Baumgarten SF, Verma R, Lunov O, Dejneka A, Sullivan GJ. Liver Organoids: Recent Developments, Limitations and Potential. Front Med [Internet]. 2021 May 5 [cited 2025 Mar 4];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.574047/full. [CrossRef]

- Orford KW, Scadden DT. Deconstructing stem cell self-renewal: genetic insights into cell-cycle regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008 Feb;9(2):115–28. [CrossRef]

- Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008 Feb 22;132(4):598–611. [CrossRef]

- Godoy P, Hewitt NJ, Albrecht U, Andersen ME, Ansari N, Bhattacharya S, et al. Recent advances in 2D and 3D in vitro systems using primary hepatocytes, alternative hepatocyte sources and non-parenchymal liver cells and their use in investigating mechanisms of hepatotoxicity, cell signaling and ADME. Arch Toxicol. 2013 Aug;87(8):1315–530. [CrossRef]

- Lu P, Ruan D, Huang M, Tian M, Zhu K, Gan Z, et al. Harnessing the potential of hydrogels for advanced therapeutic applications: current achievements and future directions. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Jul 1;9(1):1–66. [CrossRef]

- Barajaa MA, Otsuka T, Ghosh D, Kan HM, Laurencin CT. Development of porcine skeletal muscle extracellular matrix-derived hydrogels with improved properties and low immunogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 May 7;121(19):e2322822121. [CrossRef]

- Ong J, Gibbons G, Siang LY, Lei Z, Zhao J, Justin AW, et al. A clinically defined and xeno-free hydrogel system for regenerative medicine [Internet]. bioRxiv; 2025 [cited 2025 Mar 4]. p. 2024.05.28.596179. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.05.28.596179v2.

- Talbot NC, Caperna TJ. Proteome array identification of bioactive soluble proteins/peptides in Matrigel: relevance to stem cell responses. Cytotechnology. 2015 Oct;67(5):873–83. [CrossRef]

- Vukicevic S, Kleinman HK, Luyten FP, Roberts AB, Roche NS, Reddi AH. Identification of multiple active growth factors in basement membrane Matrigel suggests caution in interpretation of cellular activity related to extracellular matrix components. Exp Cell Res. 1992 Sep;202(1):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hughes CS, Postovit LM, Lajoie GA. Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics. 2010 May;10(9):1886–90. [CrossRef]

- Soofi SS, Last JA, Liliensiek SJ, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. The elastic modulus of Matrigel as determined by atomic force microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2009 Sep;167(3):216–9. [CrossRef]

- Kohen NT, Little LE, Healy KE. Characterization of Matrigel interfaces during defined human embryonic stem cell culture. Biointerphases. 2009 Dec;4(4):69–79. [CrossRef]

- Serban MA, Liu Y, Prestwich GD. Effects of extracellular matrix analogues on primary human fibroblast behavior. Acta Biomater. 2008 Jan;4(1):67–75. [CrossRef]

- Aisenbrey EA, Murphy WL. Synthetic alternatives to Matrigel. Nat Rev Mater. 2020 Jul;5(7):539–51. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Bockhorn J, Dalton R, Chang YF, Qian D, Zitzow LA, et al. Removal of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus from human-in-mouse breast tumor xenografts by cell-sorting. J Virol Methods. 2011 May;173(2):266–70. [CrossRef]

- Peterson NC. From bench to cageside: Risk assessment for rodent pathogen contamination of cells and biologics. ILAR J. 2008;49(3):310–5. [CrossRef]

- Segers VFM, Lee RT. Biomaterials to enhance stem cell function in the heart. Circ Res. 2011 Sep 30;109(8):910–22. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372:n71.

- Jiang S, Xu F, Jin M, Wang Z, Xu X, Zhou Y, et al. Development of a high-throughput micropatterned agarose scaffold for consistent and reproducible hPSC-derived liver organoids. Biofabrication. 2022 Oct;15(1):015006. [CrossRef]

- Fan H, Shang J, Li J, Yang B, Zhou D, Jiang S, et al. High-Throughput Formation of Pre-Vascularized hiPSC-Derived Hepatobiliary Organoids on a Chip via Nonparenchymal Cell Grafting. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025 Feb;12(8):e2407945. [CrossRef]

- Duarte Campos DF, Blaeser A, Korsten A, Neuss S, Jäkel J, Vogt M, et al. The stiffness and structure of three-dimensional printed hydrogels direct the differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells toward adipogenic and osteogenic lineages. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015 Feb;21(3–4):740–56. [CrossRef]

- Roudaut M, Caillaud A, Souguir Z, Bray L, Girardeau A, Rimbert A, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived liver organoids grown on a Biomimesys®® hyaluronic acid-based hydroscaffold as a new model for studying human lipoprotein metabolism. Bioeng Transl Med. 2024 Jul;9(4):e10659. [CrossRef]

- Di Matteo S, Di Meo C, Carpino G, Zoratto N, Cardinale V, Nevi L, et al. Therapeutic effects of dexamethasone-loaded hyaluronan nanogels in the experimental cholestasis. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022 Aug;12(8):1959–73. [CrossRef]

- Zhang CJ, Meyer SR, O’Meara MJ, Huang S, Capeling MM, Ferrer-Torres D, et al. A human liver organoid screening platform for DILI risk prediction. J Hepatol. 2023 May;78(5):998–1006.

- Gil-Recio C, Montori S, Al Demour S, Ababneh MA, Ferrés-Padró E, Marti C, et al. Chemically Defined Conditions Mediate an Efficient Induction of Dental Pulp Pluripotent-Like Stem Cells into Hepatocyte-Like Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021:5212852. [CrossRef]

- Yuniartha R, Yamaza T, Sonoda S, Yoshimaru K, Matsuura T, Yamaza H, et al. Cholangiogenic potential of human deciduous pulp stem cell-converted hepatocyte-like cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021 Jan 13;12(1):57. [CrossRef]

- Mitani S, Onodera Y, Hosoda C, Takabayashi Y, Sakata A, Shima M, et al. Generation of functional liver sinusoidal endothelial-like cells from human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Regen Ther. 2023 Dec;24:274–81. [CrossRef]

- Danoy M, Jellali R, Tauran Y, Bruce J, Leduc M, Gilard F, et al. Characterization of the proteome and metabolome of human liver sinusoidal endothelial-like cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. Differentiation. 2021;120:28–35. [CrossRef]

- Son JS, Park CY, Lee G, Park JY, Kim HJ, Kim G, et al. Therapeutic correction of hemophilia A using 2D endothelial cells and multicellular 3D organoids derived from CRISPR/Cas9-engineered patient iPSCs. Biomaterials. 2022 Apr;283:121429. [CrossRef]

- Wu R, Li H, Yang Y, Zheng Q, Li S, Chen Y. Bioactive Silk Fibroin-Based Hybrid Biomaterials for Musculoskeletal Engineering: Recent Progress and Perspectives. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2021 Sep 20;4(9):6630–46. [CrossRef]

- Huang TY, Wang GS, Ko CS, Chen XW, Su WT. A study of the differentiation of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth on 3D silk fibroin scaffolds using static and dynamic culture paradigms. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020 Apr;109:110563. [CrossRef]

- Pook M, Teino I, Kallas A, Maimets T, Ingerpuu S, Jaks V. Changes in Laminin Expression Pattern during Early Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138346. [CrossRef]

- Rodin S, Antonsson L, Niaudet C, Simonson OE, Salmela E, Hansson EM, et al. Clonal culturing of human embryonic stem cells on laminin-521/E-cadherin matrix in defined and xeno-free environment. Nat Commun. 2014 Jan 27;5(1):3195. [CrossRef]

- Horejs CM, Serio A, Purvis A, Gormley AJ, Bertazzo S, Poliniewicz A, et al. Biologically-active laminin-111 fragment that modulates the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Apr 22;111(16):5908–13. [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Clin Invest. 2009 Jun;119(6):1429–37.

- Wang Z, Ye S, van der Laan LJW, Schneeberger K, Masereeuw R, Spee B. Chemically Defined Organoid Culture System for Cholangiocyte Differentiation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024 Dec;13(30):e2401511.

- Carpentier N, Ye S, Delemarre MD, Van der Meeren L, Skirtach AG, van der Laan LJW, et al. Gelatin-Based Hybrid Hydrogels as Matrices for Organoid Culture. Biomacromolecules. 2024 Feb 12;25(2):590–604.

- Passaretta F, Bosco D, Centurione L, Centurione MA, Marongiu F, Di Pietro R. Differential response to hepatic differentiation stimuli of amniotic epithelial cells isolated from four regions of the amniotic membrane. J Cell Mol Med. 2020 Apr;24(7):4350–5. [CrossRef]

- Ong J, Serra MP, Segal J, Cujba AM, Ng SS, Butler R, et al. Imaging-Based Screen Identifies Laminin 411 as a Physiologically Relevant Niche Factor with Importance for i-Hep Applications. Stem Cell Reports. 2018 Mar 13;10(3):693–702. [CrossRef]

- Takayama K, Mitani S, Nagamoto Y, Sakurai F, Tachibana M, Taniguchi Y, et al. Laminin 411 and 511 promote the cholangiocyte differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2016 May 20;474(1):91–6. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Toprakhisar B, Van Haele M, Antoranz A, Boon R, Chesnais F, et al. A fully defined matrix to support a pluripotent stem cell derived multi-cell-liver steatohepatitis and fibrosis model. Biomaterials. 2021 Sep;276:121006. [CrossRef]

- Blackford SJI, Yu TTL, Norman MDA, Syanda AM, Manolakakis M, Lachowski D, et al. RGD density along with substrate stiffness regulate hPSC hepatocyte functionality through YAP signalling. Biomaterials. 2023 Feb;293:121982. [CrossRef]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000097.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).