Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collected Data

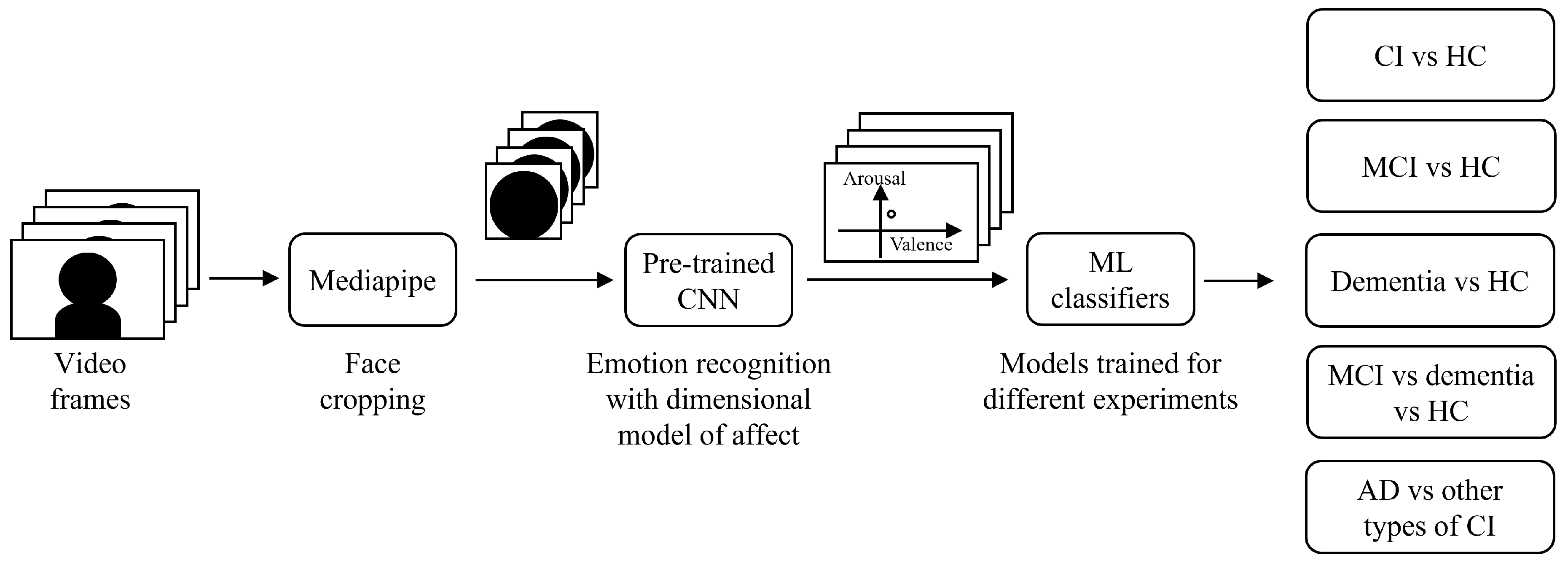

2.2. System Architecture and Data Processing

2.3. Experiments

- CI vs HC. In this experiment, all CI subjects were grouped together and compared with the HC group by performing a binary classification. This allowed to validate the generalization capability of the proposed algorithm when tested on this enlarged dataset against that in [18]. The considered dataset included 64 subjects: 36 CI (26 MCI + 10 overt dementia) and 28 HC.

- MCI vs HC. Among the CI subjects, in this experiment we selected only those clinically diagnosed as MCI. The objective was to investigate if differences with respect to HC could be spotted also in the earlier phase of the disease. The considered dataset included 54 subjects: 26 MCI and 28 HC. We performed binary classification to distinguish these two classes.

- Dementia vs HC. In contrast to the previous experiment, in this one we selected only overt dementia patients, to focus on the differences with respect to HC that could be spotted at a later phase of the disease. The considered dataset included 38 subjects: 10 overt dementia and 28 HC. We performed binary classification to distinguish these two classes.

- MCI vs dementia vs HC. In this experiment, we compared the three different classes of subjects, according to the level of severity of the disease. The considered dataset included 64 subjects: 26 MCI, 10 overt dementia, and 28 HC. We moved from a binary to a multiclass classification problem to distinguish these three classes. It must be noticed that the dataset was imbalanced across classes, as the overt dementia class included fewer subjects compared to the other two groups.

- AD vs other types of CI. In this last experiment, the aim was to investigate differences in facial emotion responses among individuals with different types of CI. Specifically, we grouped together patients diagnosed with AD, and compared them to the broader group of individuals with other forms of CI. This approach was motivated by the fact that AD is the most common cause of dementia, and a differential diagnosis distinguishing AD from other etiologies is of critical clinical importance. The considered dataset included 36 subjects: 26 MCI (13: due to AD; 13: other types), and 10 overt dementia (4: AD, 6: other types). We considered two classes: AD (17 subjects), and other types of CI (19 subjects). We performed binary classification to distinguish these two classes.

2.4. Model Selection and Evaluation

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global status report on the public health response to dementia, 2021.

- Scheltens, P.; Blennow, K.; Breteler, M.M.; De Strooper, B.; Frisoni, G.B.; Salloway, S.; Van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet 2016, 388, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T O’Brien, J.; Thomas, A. Vascular dementia. The Lancet 2015, 386, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, J.; Spina, S.; Miller, B.L. Frontotemporal dementia. The Lancet 2015, 386, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, Z.; Possin, K.L.; Boeve, B.F.; Aarsland, D. Lewy body dementias. The Lancet 2015, 386, 1683–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, A.; Okereke, O.I.; Yang, T.; Blacker, D.; Selkoe, D.J.; Grodstein, F. Plasma amyloid-β as a predictor of dementia and cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of neurology 2012, 69, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.C.; Emerson, S.; Kesselheim, A.S. Evaluation of aducanumab for Alzheimer disease: scientific evidence and regulatory review involving efficacy, safety, and futility. Jama 2021, 325, 1717–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.S.; DeKosky, S.T.; Dickson, D.; Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Fox, N.C.; Gamst, A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia 2011, 7, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.H.; Lwi, S.J.; Hua, A.Y.; Haase, C.M.; Miller, B.L.; Levenson, R.W. Increased subjective experience of non-target emotions in patients with frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2017, 15, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, P.S.; Chen, K.H.; Casey, J.; Sillau, S.; Chial, H.J.; Filley, C.M.; Miller, B.L.; Levenson, R.W. Incongruences between facial expression and self-reported emotional reactivity in frontotemporal dementia and related disorders. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences 2023, 35, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dodge, H.H.; Mahoor, M.H. MC-ViViT: Multi-branch Classifier-ViViT to detect Mild Cognitive Impairment in older adults using facial videos. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 238, 121929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, H.H.; Yu, K.; Wu, C.Y.; Pruitt, P.J.; Asgari, M.; Kaye, J.A.; Hampstead, B.M.; Struble, L.; Potempa, K.; Lichtenberg, P.; et al. Internet-Based Conversational Engagement Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial (I-CONECT) Among Socially Isolated Adults 75+ Years Old With Normal Cognition or Mild Cognitive Impairment: Topline Results. The Gerontologist 2023, 64, gnad147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeda-Kameyama, Y.; Kameyama, M.; Tanaka, T.; Son, B.K.; Kojima, T.; Fukasawa, M.; Iizuka, T.; Ogawa, S.; Iijima, K.; Akishita, M. Screening of Alzheimer’s disease by facial complexion using artificial intelligence. Aging (Albany NY) 2021, 13, 1765–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Bouazizi, M.; Ohtsuki, T.; Kitazawa, M.; Horigome, T.; Kishimoto, T. Detecting Dementia from Face-Related Features with Automated Computational Methods. Bioengineering 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, T.; Takamiya, A.; Liang, K.; Funaki, K.; Fujita, T.; Kitazawa, M.; Yoshimura, M.; Tazawa, Y.; Horigome, T.; Eguchi, Y.; et al. The project for objective measures using computational psychiatry technology (PROMPT): Rationale, design, and methodology. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 2020, 19, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Yang, E.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, W. A Novel deep neural network-based emotion analysis system for automatic detection of mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. Neurocomputing 2022, 468, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamasco, L.; Lorenzo, F.; Coletta, A.; Olmo, G.; Cermelli, A.; Rubino, E.; Rainero, I. Automatic Detection of Cognitive Impairment through Facial Emotion Analysis. SSRN preprint. [CrossRef]

- Okunishi, T.; Zheng, C.; Bouazizi, M.; Ohtsuki, T.; Kitazawa, M.; Horigome, T.; Kishimoto, T. Dementia and MCI Detection Based on Comprehensive Facial Expression Analysis From Videos During Conversation. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2025, 29, 3537–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.S.; Wang, D.Y.; Liang, C.K.; Chou, M.Y.; Hsu, Y.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Liao, M.C.; Chu, W.T.; Lin, Y.T. Automated Video Analysis of Audio-Visual Approaches to Predict and Detect Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Older Adults. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2023, 92, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Seyedi, S.; Haque, R.U.; Pongos, A.L.; Vickers, K.L.; Manzanares, C.M.; Lah, J.J.; Levey, A.I.; Clifford, G.D. Automated analysis of facial emotions in subjects with cognitive impairment. Plos one 2022, 17, e0262527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Cuthbert, B.N. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual. Technical Report Technical Report A-8, University of Florida, NIMH Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, 2008.

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. The International Affective Digitized Sounds (IADS-2): Affective Ratings of Sounds and Instruction Manual. Technical Report Technical Report B-3, University of Florida, NIMH Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, 2007.

- Peirce, J.; Gray, J.R.; Simpson, S.; MacAskill, M.; Höchenberger, R.; Sogo, H.; Kastman, E.; Lindeløv, J.K. PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behavior research methods 2019, 51, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack Jr, C.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack Jr, C.R.; Andrews, J.S.; Beach, T.G.; Buracchio, T.; Dunn, B.; Graf, A.; Hansson, O.; Ho, C.; Jagust, W.; McDade, E.; et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2024, 20, 5143–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Festari, C.; Massa, F.; Ramusino, M.C.; Orini, S.; Aarsland, D.; Agosta, F.; Babiloni, C.; Borroni, B.; Cappa, S.F.; et al. European intersocietal recommendations for the biomarker-based diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders. The Lancet Neurology 2024, 23, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rascovsky, K.; Hodges, J.R.; Knopman, D.; Mendez, M.F.; Kramer, J.H.; Neuhaus, J.; Van Swieten, J.C.; Seelaar, H.; Dopper, E.G.; Onyike, C.U.; et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011, 134, 2456–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Dickson, D.W.; Halliday, G.; Taylor, J.P.; Weintraub, D.; Aarsland, D.; Galvin, J.; Attems, J.; Ballard, C.G.; et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2017, 89, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, P.; Kalaria, R.; O’Brien, J.; Skoog, I.; Alladi, S.; Black, S.E.; Blacker, D.; Blazer, D.G.; Chen, C.; Chui, H.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders 2014, 28, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.M.; Galantucci, S.; Tartaglia, M.C.; Gorno-Tempini, M.L. The neural basis of syntactic deficits in primary progressive aphasia. Brain and Language 2012, 122, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugaresi, C.; Tang, J.; Nash, H.; McClanahan, C.; Uboweja, E.; Hays, M.; Zhang, F.; Chang, C.L.; Yong, M.G.; Lee, J.; et al. MediaPipe: A Framework for Building Perception Pipelines. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:cs.DC/1906.08172. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal of personality and social psychology 1971, 17, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollahosseini, A.; Hasani, B.; Mahoor, M.H. Affectnet: A database for facial expression, valence, and arousal computing in the wild. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2017, 10, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, E.; Ballerini, L.; del, C. Valdes Hernandez, M.; Chappell, F.M.; González-Castro, V.; Anblagan, D.; Danso, S.; Muñoz-Maniega, S.; Job, D.; Pernet, C.; et al. Machine learning of neuroimaging for assisted diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2018, 10, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jin, K.; Zhou, D.; Kubota, N.; Ju, Z. Attention mechanism-based CNN for facial expression recognition. Neurocomputing 2020, 411, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Huang, C.; Wang, X.; Jiang, F. Facial expression recognition with grid-wise attention and visual transformer. Information Sciences 2021, 580, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MCI | Overt dementia | Healthy controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 26 | 10 | 28 |

| Age (mean ±standard deviation) | 68.2 ±9.3 | 72.9 ±3.8 | 58.8 ±6.9 |

| Sex (number of females, %) | 10 (38.5%) | 6 (60.0%) | 14 (50.0%) |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | Caucasian | Caucasian |

| Years of education (mean ±standard deviation) | 13.7 ±4.6 | 10.4 ±5.4 | 15.6 ±4.8 |

| MMSE score (mean ±standard deviation) | 25.8 ±3.6 | 18.8 ±5.5 | 29.2 ±1.2 |

| MoCA score (mean ±standard deviation) | 20.0 ±4.4 | 14.0 ±3.6 | 25.4 ±2.2 |

| Differential CI diagnosis | 13: due to AD; 13: other types | 4: AD; 6: other types | No cognitive impairment |

| Experiment | Model | Parameters | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| CI vs HC | KNN | 3 neighbors, Manhattan distance | 0.736 ±0.102 |

| LR | L2 penalty, tolerance=0.0001, C=0.001 | 0.623 ±0.139 | |

| SVM | linear kernel, tolerance=0.001, C=0.01 | 0.624 ±0.092 | |

| MCI vs HC | KNN | 3 neighbors, Manhattan distance | 0.760 ±0.041 |

| LR | L2 penalty, tolerance=0.0001, C=0.001 | 0.684 ±0.114 | |

| SVM | linear kernel, tolerance=0.001, C=0.001 | 0.667 ±0.069 | |

| Dementia vs HC | KNN | 3 neighbors, Euclidean distance | 0.732 ±0.097 |

| LR | L2 penalty, tolerance=0.0001, C=0.1 | 0.654 ±0.145 | |

| SVM | linear kernel, tolerance=0.001, C=0.0001 | 0.736 ±0.018 | |

| MCI vs dementia vs HC | KNN | 5 neighbors, Manhattan distance | 0.641 ±0.103 |

| LR | L2 penalty, tolerance=0.0001, C=0.01 | 0.591 ±0.104 | |

| SVM | linear kernel, tolerance=0.001, C=0.1 | 0.578 ±0.077 |

| Experiment | Model | Parameters | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD vs other types of CI | KNN | 5 neighbors, Chebyshev distance | 0.754 ±0.128 |

| LR | L2 penalty, tolerance=0.0001, C=0.0001 | 0.586 ±0.171 | |

| SVM | linear kernel, tolerance=0.001, C=0.01 | 0.643 ±0.090 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).