1. Introduction

Emotion recognition, a key technology in human-computer interaction (HCI) and a core application of artificial intelligence (AI) [

1], allows computer systems to accurately perceive human emotional states in real-time. This capability enables adaptive HCI models, forming the foundation for natural user experiences. Significant progress in emotion recognition has led to its widespread use in diverse applications, including driver rage detection [

2], specialized patient care [

3], and adolescent mental health assessment [

4].

While unimodal recognition using facial expressions or physiological signals is well-established, emotion as a complex psychophysiological phenomenon often lacks robustness when analyzed through single modalities or even fused physiological signals alone [

5]. Current research primarily uses visual data (e.g., facial images, video) and physiological data (e.g., EEG, ECG, GSR) [

6]. Facial expressions, observable emotional cues, are easily captured via cameras, with features extractable by handcrafted or deep learning methods. Physiological signals, originating from nervous system activity, are less susceptible to conscious control and may better reflect genuine emotional states. However, physiological signal acquisition faces challenges like hardware heterogeneity and specialized preprocessing needs, limiting deep learning exploration for this modality. Fusing visual and physiological data is essential for more accurate emotion recognition. Yet, current models often use simple feature concatenation before classification, failing to capture deep inter-modal correlations and complementarity, thus limiting performance gains. Furthermore, both subtle facial changes and rhythmic physiological fluctuations are inherently temporal processes. Existing research, to our knowledge, lacks systematic modeling of this crucial temporal dynamic.

Therefore, this study focuses on improving feature extraction methods for visual (facial images) and physiological signals, while exploring more effective multimodal feature fusion strategies, aiming to improve the performance of affective computing systems in terms of both prediction reliability and generalization capability. Specifically, we design a computationally efficient, ConvNeXt V2-based feature extractor for facial expression analysis that better captures spatiotemporal features in long facial image sequences. For physiological signal processing, we innovatively propose a “Local-Medium-Global” hierarchical feature extraction framework. This framework synergistically captures transient local details, rhythmic mid-range patterns, and global temporal dynamics within physiological signals, significantly reducing computational complexity while maintaining performance. Crucially, at the feature fusion stage, we introduce a Gated Attention Mechanism. This mechanism dynamically learns complex nonlinear inter-modal interactions, enabling adaptive deep synergistic fusion of cross-modal features, thereby driving substantial improvements in recognition performance.

In summary, this paper makes three core contributions:

To address the inefficient modeling of coupled spatio-temporal features in continuous facial expression sequences, we introduce a computationally efficient synergistic architecture combining ConvNeXt V2 and lightweight Transformers for efficient spatio-temporal dynamic feature extraction.

To overcome the challenge of unified modeling for multi-scale temporal patterns in physiological signals (transient local, rhythmic mid-range, and global dependencies), we develop a novel three-level hybrid feature extraction framework (“Local-Medium-Global”). This framework ensures computational efficiency while comprehensively capturing cross-scale bio-features.

To mitigate the limitations of simple feature concatenation, such as modal redundancy and lack of complementarity, we propose a feature fusion module based on a Gated Attention Mechanism. This module adaptively learns and modulates the contribution weights of features from different modalities, enabling deep interaction and optimal collaboration at the feature level, effectively overcoming the drawbacks of naive concatenation.

The structure of the subsequent sections of this paper is as follows: Part II discusses the latest methods for extracting features from facial information and physiological signals (especially electroencephalograms) as a means of multimodal emotion recognition. Section III provides a detailed introduction to GBV-Net, a hierarchical fusion multimodal emotion recognition model based on facial expressions and physiological signals. Section IV systematically describes the experimental framework, the datasets utilized, and the evaluation metrics employed, presents the results, and provides comparative analyses against existing methods. Finally, Section V summarizes the work, accompanied by a discourse on prospective avenues for future research.

2. Related Work

Emotion recognition holds significant value for diverse applications, including human-computer interaction (HCI) and mental health assessment. This importance has motivated substantial research interest in recent years. Consequently, the field has established itself as a systematic research domain. From a technical implementation perspective, emotion recognition systems based on deep learning are categorised primarily into two types according to the modality of the input data: unimodal and multimodal.

2.1. Unimodal Emotion Recognition

Unimodal emotion recognition employs a solitary data modality, encompassing facial expressions, physiological signals, text, or speech data. However, due to the susceptibility of unimodal data to noise and the inherent complexity of emotion recognition, the dependability and authenticity of results derived from models based solely on unimodal data are frequently questioned.

2.1.1. Emotion Recognition from Facial Expressions

Facial expressions serve as a spontaneous and inherent manifestation of an individual’s psychological disposition, conveying a complex array of emotional information. Facial Expression Recognition (FER) aims to infer emotional states by analyzing facial expressions in multimedia data like images and videos. Driven by advances in multimedia technology, FER has become a prominent area of research focus in the fields of computer vision and artificial intelligence due to its broad application prospects. Meena et al. [

7] developed a CNN solution capable of handling large-scale signal data. Their optimization strategy employed larger batch sizes, increased convolutional layer depth, and extended training epochs to enhance model performance. Similarly, focusing on architectural innovation, Chowdary et al. [

8] systematically evaluated four transfer learning frameworks. By removing the fully connected layers of previously trained CNNs and reconstructing task-specific FC layers, they achieved an average recognition accuracy of 96% on 918 images from the Cohn-Kanade (CK+) database. Expanding application scenarios further, Minaee et al. [

9] addressed challenges in FER, notably high intra-class variance and the poor generalization of traditional handcrafted features, by proposing an attention-based convolutional network model. Their method, which focuses on key facial regions, significantly outperformed existing models on four benchmark datasets, including FER-2013. Innovatively, they combined visualization techniques to reveal facial regions sensitive to different emotions. This end-to-end framework effectively overcame challenges like partial occlusion and image variations, offering a new approach for expression recognition in complex scenarios.

2.1.2. Emotion Recognition from Physiological Signals

Compared to facial expressions, the core advantage of physiological signals lies in their authenticity and resistance to voluntary control, enabling a more objective assessment of emotional states. Recent research has primarily focused on EEG signals, alongside other physiological signals such as EMG, ECG, and GSR, yielding encouraging results. Zhu et al. [

10] extracted Differential Entropy (DE) features from EEG signals, employed a Linear Dynamic System (LDS) for feature smoothing, and ultimately used a Support Vector Machine (SVM) for classification. Bhatti et al. [

11] extracted time-domain and frequency-domain features from EEG signals and fed them directly into a classifier for emotion recognition. Algarni et al. [

12] proposed a system framework aimed at enhancing the reliability of emotion recognition results to support precise medical decision-making. The framework’s initial phase involved the extraction of wavelet features, the Hurst exponent, and statistical features from EEG signals. Subsequently, a Binary Grey Wolf Optimization (BGWO) algorithm is employed for feature selection to identify the most discriminative patterns. Finally, a stacked Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) network was utilized for emotion classification based on the selected features.

2.2. Multimodal Emotion Recognition

In recent years, multimodal emotion recognition has attracted significant research interest. The integration of physiological signals, particularly EEG, with facial expression features has become an increasingly explored subject in research. This fusion method utilizes complementary information from both modalities. Combining these features provides a more comprehensive characterization of emotional states. Consequently, recognition performance improves substantially. Salama et al [

13]. implemented this approach by converting brief EEG data into three-dimensional blocks. These blocks were then combined with synchronized sequences of facial images within corresponding temporal windows. Siddharth et al. [

14] extracted features from facial image sequences, EEG signals, and peripheral physiological signals (e.g., ECG, GSR), achieving feature-level fusion through vector concatenation. Huang et al. [

15] employed Adaptive Boosting (Adaboost) combined with a decision-level fusion strategy to integrate facial and EEG modality information, resulting in improved recognition accuracy. Xiang et al. [

16] elicited emotions in subjects, simultaneously collected facial expression videos and physiological signals, and designed a Spatiotemporal Convolutional Neural Network (Spatiotemporal CNN) to analyze the performance of different modalities in emotion recognition.

However, despite the potential of multimodal fusion to enhance accuracy, current mainstream methods exhibit significant limitations in their feature fusion strategies. Existing approaches predominantly rely on simplistic linear weighting or feature concatenation [

17], failing to deeply explore and model the potential complex nonlinear correlations and complementarities between features from different modalities. This shallow fusion mechanism struggles to fully exploit inter-modal synergies, limiting further improvements in model performance.

To address the challenge of feature fusion, this paper proposes an efficient method based on a gated attention mechanism. It aims to explicitly model and enhance the intrinsic relationships between multimodal information, thereby driving substantial improvements in multimodal emotion recognition performance. Specifically, we propose a model based on a modified ConvNeXt V2 architecture incorporating lightweight Transformers, designed to extract robust spatio-temporal dynamic features from facial image sequences. Concurrently, we design an innovative three-tier hybrid feature extraction framework (“Local-Medium-Global”) to efficiently capture fine-grained local patterns, mid-range rhythmic regularities, and global temporal dependencies within multimodal physiological signals. Finally, at the feature level, we introduce a Gated Attention Mechanism to perform adaptive deep fusion of the extracted facial and physiological features, fully mining their intrinsic relationships. The resulting fused features are then fed into a classifier to complete the emotion recognition task.

3. Methodology

3.1. GBV-Net Architecture Overview

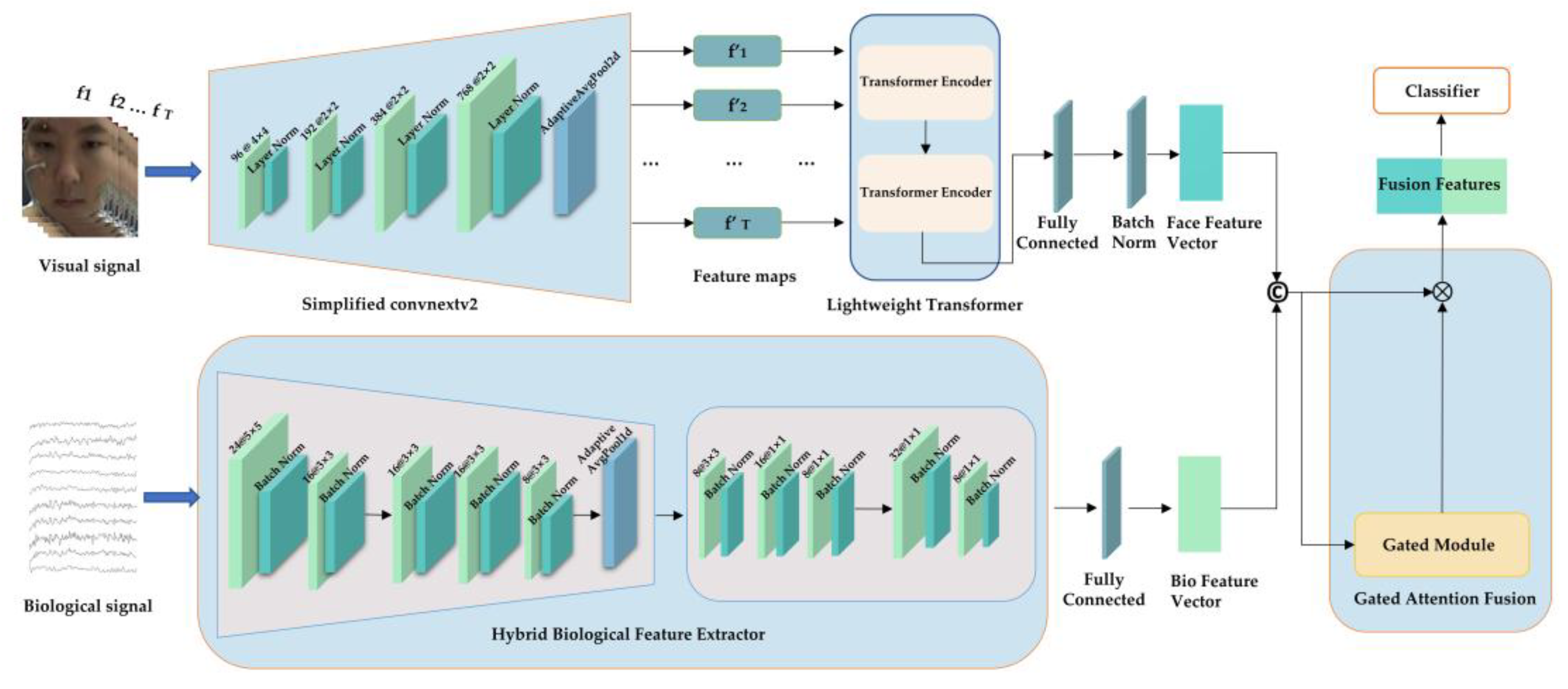

Figure 1 shows the Gated Biological Visual Network multimodal emotion recognition model proposed in this paper. Emotion recognition is achieved through the collaborative learning of visual and physiological signals. The model’s core includes a visual feature extractor based on an enhanced ConvNeXt V2, as well as a hybrid physiological feature extractor. The former uses a spatiotemporal encoder to capture the spatiotemporal evolution features of facial expressions, while the latter uses multi-scale convolutions and self-attention mechanisms to extract deep features from physiological signals. The innovative gated fusion module aligns cross-modal features through adaptive weight allocation, and the classifier outputs emotion prediction probabilities. This architecture optimises multimodal feature representations through end-to-end training, significantly improving cross-modal feature complementarity while ensuring computational efficiency.

3.2. Multimodal Feature Extraction

This section describes methods for extracting features from visual signals and physiological signals. For visual signals, an improved ConvNeXt V2 architecture is employed, extracting static features through four levels of spatial downsampling and capturing temporal dynamics using a two-layer Transformer. Physiological signal processing uses a hybrid architecture that combines multi-scale 1D convolution, temporal convolution, and convolutional self-attention mechanisms to extract feature sequences. These are ultimately output as deep representations through a feature integration layer.

3.2.1. Facial Feature Extraction

For facial features, the present study proposes a facial expression feature extraction architecture. By leveraging a modified ConvNeXt V2 architecture [

18] and a lightweight Transformer temporal modeling module [

19], it achieves joint modeling of spatial features and temporal dynamic features. This architecture divides facial feature extraction into two consecutive processing stages: spatial feature extraction and temporal dynamic modeling, significantly enhancing computational efficiency while ensuring feature discriminability.

In the spatial feature extraction stage, a modified ConvNeXt V2 architecture is employed for multi-level feature extraction. This module first employs a 4x4 convolutional layer with a stride of 4 on the input image to a low-resolution feature space. The convolutional operation is expressed as follows:

In which X stands for the input facial image feature map, W is the convolution kernel of size K x K, b indicates the bias, i and j denote the spatial coordinates of the feature map, and Y represents the output feature map.

Subsequently, we perform feature transformation and dimensionality enhancement through a series of modular components consisting of convolutional layers, Layer Normalization (LayerNorm), and the GELU activation function. Compared to the original ConvNeXt V2, we simplified the network’s depth and width while retaining its efficient feature extraction capability. This architecture employs a layer-wise, dimension-increasing design that enables the network to capture multi-scale facial features, from local details to global semantics, at different hierarchical levels. The introduction of a lightweight Transformer module was made for the purpose of modeling temporal dependencies within the expression sequence, given the dynamic evolution of facial expressions over time. This module consists of a 2-layer Transformer encoder, where each encoder layer incorporates a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feedforward neural network. The multi-head self-attention mechanism is shown below:

In this context, Q, K, and V in Represent the query, key, and value matrices, respectively. All of the learnable parameters are matrices, each of which has several attention heads denoted by h.

The Transformer’s input is the feature sequence processed by the spatial feature extractor. To satisfy the input requirements of the Transformer architecture, the feature sequence dimensionality is adjusted accordingly. The self-attention mechanism effectively models dependency relationships across different time steps. Compared to traditional recurrent neural networks, such as LSTMs, the Transformer can more effectively capture long-range temporal dependencies. Additionally, it supports parallel processing, which substantially enhances training efficiency.

3.2.2. Physiological Signal Feature Extraction

The bio-signals feature extraction module proposed in this study adopts a hierarchical architecture. This design integrates local feature extraction, temporal dependency modeling, and global correlation learning. It effectively captures multi-scale features and dynamic patterns inherent in bio-signals. The module consists of three core components: a local feature extractor, a temporal convolutional network (TCN), and an efficient convolutional self-attention mechanism. These components collaborate to extract deep features from bio-signals.

The Local Feature Extractor employs a CNN architecture tailored to capture transient local patterns and high-frequency features in bio-signals. This sub-module utilizes a dual-layer 1D convolutional architecture [

20]. The refinement of features is attained through a progressive reduction of feature channels and a decrease in convolutional kernel size across layers. Each layer incorporates batch normalization and ReLU activation functions. These functions accelerate training convergence and enhance the model’s nonlinear expressive capacity. The local features are as follows:

TCN [

21] captures medium-length temporal dependencies in biological signals. The module consists of three dilated convolutional layers with progressively increasing dilation rates. By introducing gaps within the convolutional kernel, the receptive field expands exponentially. This expansion enables the extraction of dynamic features across multiple time scales. Each dilated convolution is followed by batch normalization and a ReLU activation function. The final layer reduces the feature dimension to eight. Medium-length feature extraction is represented as follows:

In which d is the expansion rate and Wd is the weight. By adjusting the expansion rate, TCN can effectively model medium-range dependencies in signals without increasing parameters and computation.

For the global dependency modeling stage in bio-signals feature extraction, we employ an efficient convolutional self-attention mechanism. This module first extracts local feature patterns through depthwise convolution operations. Subsequently, pointwise convolution adjusts channel dimensionality to capture richer feature representations. Building upon these features, a self-attention mechanism is subsequently delineated as a means to model long-range dependencies among features, thereby enabling the model to adaptively focus on salient discriminative segments within the signal sequence. Finally, feature transformation is performed via a lightweight feedforward network, and residual connections are incorporated to further enhance feature flow and gradient propagation. This design ensures computational efficiency and representational capacity while capturing global dependencies. The architecture effectively strikes a balance between model complexity and performance, making it particularly well-suited for processing long-sequence bio-signals data. Long-distance global associations are as follows:

In this formulation, Convdepth and Convpoint represent depth-wise and point-wise convolution operations, respectively. Attention is indicative of the incorporated self-attention mechanism. FFN is an acronym for feedforward network, and Residual signifies the residual connection.

3.3. Feature Fusion

According to the latest findings in the neurosciences, the processing of emotions in humans is supported by a distributed network involving coordinated activity across multiple brain regions [

22]. This network comprises several key nodes, including the occipitotemporal neocortex, which facilitates visual integration; the amygdala, which processes affective evaluations; the orbitofrontal cortex, which governs value-based decision-making; and the right frontoparietal cortex, which regulates spatial attention [

23]. During the process of emotional regulation, the brain concurrently processes multisource heterogeneous physiological and visual signals [

24]. Consequently, computational models that can effectively integrate multimodal features provide a more biologically plausible approach, aligning with the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying emotion generation.

The fusion module proposed in this study employs a gated attention fusion strategy, with the objective of achieving adaptive integration of facial expression and bio-signals attributes. The core design of the fusion module aims to dynamically balance the contribution weights of features from different modalities, effectively addressing the issues of complementarity and redundancy inherent in multimodal data. Specifically, a simplified ConvNeXt V2 network is initially employed to derive high-level semantic features of facial expressions, while a hybrid bio-feature extractor captures dynamic features from bio-signals. To avoid information redundancy caused by simple feature concatenation, the model incorporates a gating mechanism for fine-grained regulation of the fusion process. The combined facial and bio-signals feature vectors pass through a gating mechanism, utilizing a stack of fully connected layers with Sigmoid-based activation for multimodal fusion. This unit generates a weight vector matching the dimensionality of the input features, enabling dynamic weighting of features from disparate analytical modalities.

The primary benefit of this gated attention mechanism is its capacity to adapt the contribution of each modality to the characteristics of the input samples. When a modality’s features are of high quality, the gating unit assigns them a higher weight. Conversely, the gating unit reduces the weight when the quality is low. Compared to traditional methods such as feature concatenation or weighted averaging, the proposed gated attention fusion strategy can more effectively capture complex relationships between multimodal data. This enhancement of the model’s capacity to integrate cross-modal information leads to an improvement in emotion recognition performance. The fusion part is shown below:

In this case, Fface and Fbio represent facial features and biometric features, respectively, while Ffused represents the fused features.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

Two publicly available benchmark datasets, DEAP [

25] and MAHNOB-HCI [

26], are employed for model validation in this study. Both datasets provide multimodal physiological signals and facial expression videos recorded simultaneously, offering standardized evaluation environments for multimodal emotion recognition research. Experiments integrate nearly complete multimodal data from all available participants (after invalid samples are removed) to ensure the statistical significance of the evaluation results. Model performance was assessed using a 10-fold cross-validation strategy. This method involves the random partitioning of the dataset into ten mutually exclusive subsets. In this particular instance, the training process involves the sequential utilization of nine distinct subsets. Concurrently, the residual subset functions as the designated test set, thereby ensuring the systematic exploration of all ten combinations. The final performance metrics represent the average values across all ten test iterations. The calculation formula is as follows:

Among them, Represents the accuracy rate of the k-fold validation. This design effectively reduces the impact of random data partitioning on the results, providing a more objective reflection of the model’s generalization ability.

4.1. Experimental Dataset and Preprocessing

The DEAP dataset is a multimodal database designed for studying human emotional states. It contains synchronized recordings from 32 participants exposed to 40 emotion-eliciting video clips (each 63 seconds), capturing central neural system signals as indicated by EEG, EMG, and GSR measures, as well as peripheral physiological signals, and facial expression video streams. For each stimulus presented, participants evaluated their responses along the dimensions of Valence, Arousal, Dominance, Liking, and Familiarity. EEG signals in DEAP were downsampled. Initially, the signals were sampled at a rate of 128 hertz. Then, they underwent a bandpass filtering procedure, during which the frequencies were limited to a range between 4.0 and 45 Hz and processed with blind source separation to remove ocular artifacts. Detailed specifications are provided in

Table 1.

The MAHNOB-HCI database is another multimodal emotional database comprising recordings of 30 participants across 20 experimental sessions. It synchronously captures facial videos and central nervous system signals, peripheral physiological signals, and eye movement data. Notably, stimulus durations vary across trials, requiring precise segmentation of valid time windows based on official annotation files. Emotional annotations utilize four dimensions: the following factors must be considered: valence, arousal, control, and predictability. However, the integrity of the data from three participants was compromised, resulting in their exclusion from the study. Consequently, the analysis was based on the data from 27 participants, thereby ensuring the reliability and validity of the study’s findings. Complete dataset characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

The data preprocessing methodology employed in this study is detailed below: For facial expression data, we performed temporal sampling at 10 fps for DEAP and 12 fps for MAHNOB-HCI to sufficiently capture facial dynamics, with extracted frames undergoing pose-normalized alignment using 68 facial landmarks detection [

27], followed by facial region cropping to preserve expression-critical features. For biosensor data, signals were downsampled to 128 Hz, bandpass-filtered, segmented using non-overlapping 1-second windows, and baseline-corrected by subtracting mean baseline values to mitigate signal drift. Regarding data augmentation, facial images employed domain-appropriate techniques including horizontal flipping, color jittering, and Gaussian blurring, distinct from augmentation methods in fields like remote sensing [

28], while bio-signals applied additive noise, temporal shifting, and amplitude scaling. Notably for EEG signals, both datasets share identical channel configurations and electrode placements (

Table 2), ensuring consistent neurophysiological feature extraction.

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

The model proposed in this paper uses a server equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4210R CPU and NVIDIA RTX A6000 graphics card implemented in the Pytorch framework. To optimize the hyperparameter settings, the batch size has been set to 256, and the learning rate has been set to 0.001. During training, the Adam algorithm is used in conjunction with an optimizer, and binary classification cross-entropy is used as the loss function.

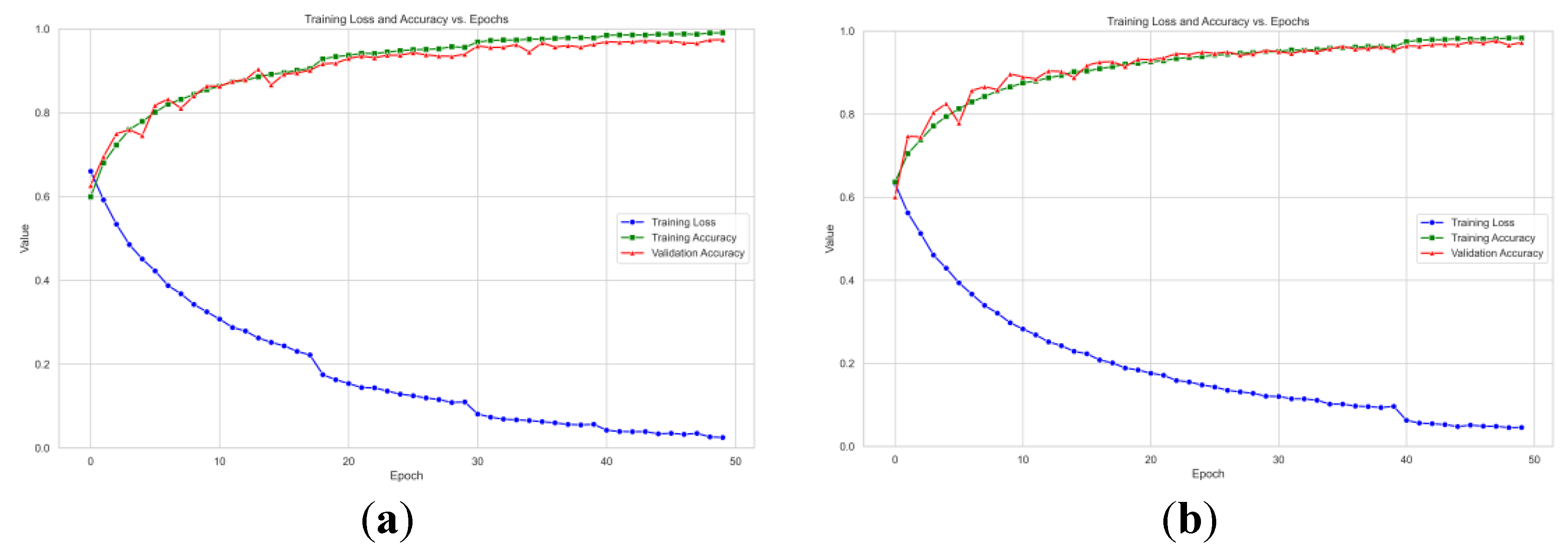

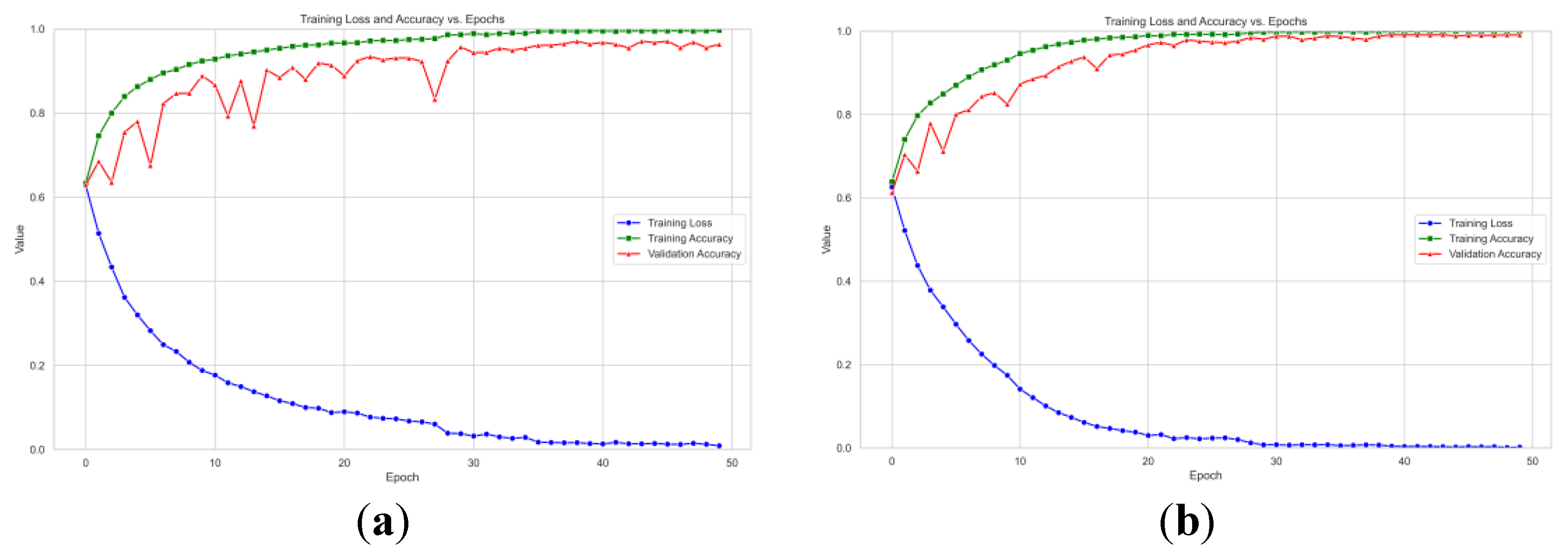

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the trends in training accuracy, validation accuracy, and training loss during the training process of the model proposed in this paper on the DEAP and MAHNOB-HCI datasets.

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, the training loss on the DEAP dataset consistently decreases with increasing iterations and eventually plateaus. This indicates that the model effectively learns data patterns and optimizes its parameters during training. Concurrently, the training accuracy exhibits a steady rise. The validation accuracy also demonstrates an overall upward trend, maintaining close alignment with the training accuracy curve. The model exhibits remarkable generalization on the DEAP dataset, as evidenced by the tight agreement between training and validation results. On the MAHNOB-HCI dataset, the training loss similarly exhibits a continuous decline, accompanied by a consistent improvement in training accuracy. Notably, despite some fluctuations in validation accuracy (

Figure 3(a)) attributed to the dataset’s more complex and heterogeneous sample distribution, the overall trend remains upward. Furthermore, the validation accuracy eventually converges towards the training accuracy. This observation demonstrates the model’s effectiveness in identifying salient emotional features and its adaptability to the challenging demands of complex datasets.

A comparative analysis of the learning curves from the DEAP and MAHNOB-HCI datasets reveals distinctive patterns. The smoother curves observed in the DEAP dataset suggest a more homogeneous data distribution, resulting in more stable model convergence. In contrast, fluctuations in the validation accuracy on the MAHNOB-HCI dataset reflect its higher inherent data complexity. Notably, these variations also demonstrate the strong robustness of GBV-Net in handling challenging and heterogeneous scenarios.

The classification accuracy of the proposed model is shown in

Table 3.

The model demonstrates notable efficacy in binary classification tasks when evaluated on the DEAP dataset. Specifically, the model achieves an accuracy of 94.68% for valence and 95.93% for arousal recognition. Notably, on the MAHNOB-HCI dataset, the model attains even higher accuracies of 97.48% for valence and 97.78% for arousal in the corresponding binary classification tasks. These results not only demonstrate a significant advantage over the accuracies reported for other existing methods listed in the table but also exhibit superior and consistent performance across both datasets and emotional dimensions. This provides robust evidence for the effectiveness and strong generalization capability of the proposed model.

To evaluate our model’s classification performance, we benchmarked it against leading multimodal emotion recognition approaches. All comparative results are provided in

Table 3. Yuvaraj et al. [

29] systematically evaluated various classical EEG features, including fractal dimension (FD) and Hjorth parameters, establishing the significance of feature engineering in identifying valence and arousal dimensions. Meanwhile, Huang [

15] proposed a multimodal emotion recognition framework integrating facial expressions and EEG, while Li et al. [

30] developed MindLink-Eumpy, an open-source toolkit for multimodal emotion recognition. These works, from the perspectives of framework design and tool implementation, respectively, validated the feasibility of significantly enhancing recognition performance through decision-level fusion strategies, offering promising approaches to overcome the limitations of unimodal methods. Furthermore, Zhang et al. [

31] introduced a hierarchical self-attention-based framework for spatiotemporal modeling, demonstrating its potential to effectively capture long-range dependencies and critical spatial information within EEG signals for improved recognition accuracy. Siddharth et al. [

14] explored the use of deep networks for processing transformed physiological signal features and multi-modal fusion, representing a trend towards deep learning advancements in this field.

Building upon the research and analysis of the aforementioned classical methods, the GBV-Net framework proposed in this paper significantly improves emotion recognition accuracy. In contrast to the hierarchical self-attention mechanism employed by Zhang et al. [

31], the proposed framework employs a spatiotemporal feature extraction architecture that synergistically integrates ConvNeXt V2 and Transformer. Specifically, in the spatial dimension, progressive downsampling enhances visual feature representation capabilities. In the temporal dimension, a lightweight Transformer encoder effectively models long-range dependencies. Unlike the static fusion strategies adopted by Huang [

15] and Li et al. [

30] for multimodal data, the present study introduces a dynamic gated attention mechanism. This mechanism facilitates the integration of facial expressions and physiological signals through a learnable feature weighting process. Departing from the classical feature engineering paradigm explored by Yuvaraj et al. [

29] and the PSD heatmap transformation method used by Siddharth et al. [

14] for physiological signal processing, GBV-Net constructs a three-stage processing pipeline: local convolution, temporal modeling, and convolutional self-attention. This pipeline implements true end-to-end deep feature learning. Additionally, the framework incorporates techniques such as adaptive pooling, residual connections, and depthwise separable convolutions. These components collectively enhance the model’s adaptability to long sequences and computational efficiency. Experimental results demonstrate that this framework surpasses the aforementioned related studies on classification tasks using both the DEAP and MAHNOB-HCI datasets, offering a superior solution for multimodal emotion recognition.

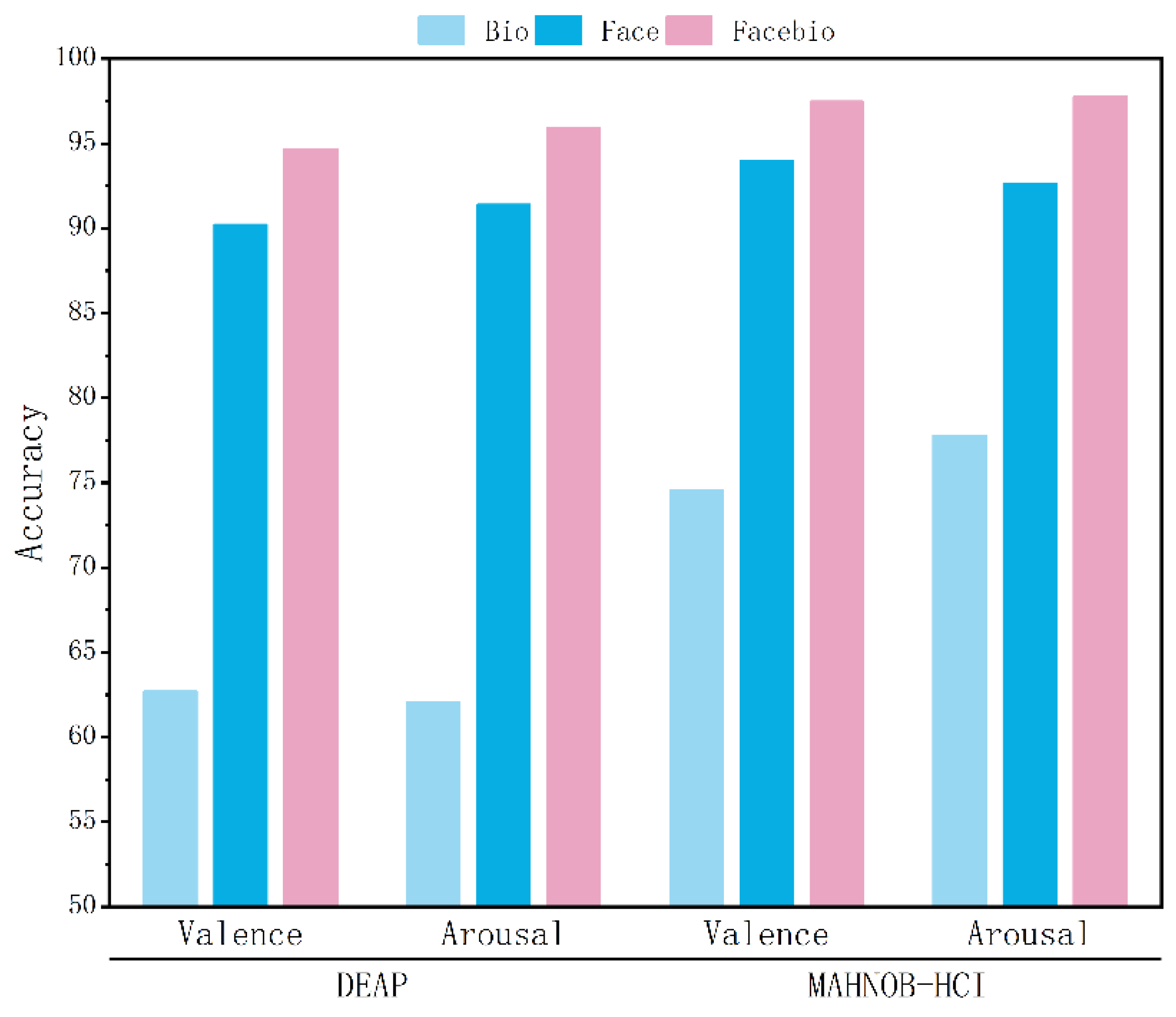

4.3. Ablation Experiment

To investigate the superiority of multimodal over unimodal emotion recognition, we conducted systematic validation across both datasets, with detailed accuracy presented in

Table 4 and ablation results visualized in

Figure 4. The facial modality demonstrated significant advantages on DEAP and MAHNOB-HCI, achieving stable accuracies exceeding 90%, while the physiological modality exhibited relatively limited performance. Multimodal fusion consistently enhanced performance: valence recognition improved by over 4 percentage points and arousal by nearly 5 percentage points on DEAP, whereas MAHNOB-HCI reached remarkable accuracies exceeding 97.5%. Notably, the performance gain for arousal consistently surpassed valence, indicating physiological signals’ unique value in capturing emotional intensity. The final fused model approached or surpassed 95% accuracy across all four tasks (valence and arousal on both datasets), peaking at 97.78%. This robust performance substantiates that facial features provide foundational discriminative power, physiological signals complement dynamic responses, and the gating fusion mechanism effectively coordinates their strengths. Cross-dataset consistency further validates GBV-Net’s generalization capability in dynamically coordinating multimodal information.

5. Conclusions

The proposed framework, termed GBV-Net, is a pioneering multimodal emotion recognition system that integrates physiological signals and facial expressions synergistically. The model extracts discriminative features directly from raw physiological data and facial video streams. It employs a gated attention fusion mechanism to dynamically weight cross-modal interactions. In terms of facial expression feature extraction, the combination of an improved ConvNeXt V2 Tiny structure and a lightweight Transformer temporal modeling module enables joint modeling of spatial features and temporal dynamic features, thereby improving feature extraction capabilities and training efficiency. Physiological signal processing adopts a three-tier hierarchical feature abstraction framework, where cascaded convolutional blocks progressively capture local motifs, mid-range dependencies, and global contextual patterns. The gated cross-attention fusion module adaptively recalibrates modality-specific contributions, significantly boosting recognition robustness. The findings of the present study demonstrate that this method achieves a high level of accuracy in identifying emotions. Combining facial expressions and physiological signals yields a superior recognition effect compared to using a single modality alone. Next, we will develop a neuron pruning strategy to optimize the computational efficiency of the model and integrate multimodal inputs, such as speech and limb behavior, to create a more comprehensive emotion recognition framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yu.jiling., Ru.yandong. and Chen.hongming.; methodology, Yu.jiling.; validation, Yu.jiling., Ru.yandong. and Lei.bangjun.; formal analysis, Yu.jiling.; writing—original draft preparation, Yu.jiling.; writing—review and editing, Yu.jiling.; funding acquisition, Ru.yandong. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study used fully public datasets (DEAP, MAHNOB-HCI) that comply with international research ethics standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EEG |

Electroencephalogram |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| GSR |

Galvanic skin response |

| Bio |

Biological |

References

- Lu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W. A Survey of Affective Brain-Computer Interface. Chin J Intell Sci Technol 2021, 3, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- De Nadai, S.; D’Inca, M.; Parodi, F.; Benza, M.; Trotta, A.; Zero, E.; Zero, L.; Sacile, R. Enhancing Safety of Transport by Road by On-Line Monitoring of Driver Emotions. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th System of Systems Engineering Conference (SoSE); IEEE: Kongsberg, Norway, June, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, U.A.; Huang, M.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Mehmood, A.; Han, H. Recommendation System Using Feature Extraction and Pattern Recognition in Clinical Care Systems. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2019, 13, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, S.; He, L.; Gao, W.; Qi, H.; Owens, G. Pervasive and Unobtrusive Emotion Sensing for Human Mental Health.

- Abdullah, S.M.S.A.; Ameen, S.Y.A.; M. Sadeeq, M.A.; Zeebaree, S. Multimodal Emotion Recognition Using Deep Learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2021, 2, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Tao, W.; Liotta, A.; Yang, D.; Li, X.; Gao, S.; Sun, Y.; Ge, W.; Zhang, W.; et al. A Systematic Review on Affective Computing: Emotion Models, Databases, and Recent Advances. Inf. Fusion 2022, 83–84, 19–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, G.; Mohbey, K.K.; Indian, A.; Khan, M.Z.; Kumar, S. Identifying Emotions from Facial Expressions Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network-Based Approach. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 83, 15711–15732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdary, M.K.; Nguyen, T.N.; Hemanth, D.J. Deep Learning-Based Facial Emotion Recognition for Human–Computer Interaction Applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 23311–23328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S.; Abdolrashidi, A. Deep-Emotion: Facial Expression Recognition Using Attentional Convolutional Network 2019.

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Zheng, W.-L.; Lu, B.-L. Cross-Subject and Cross-Gender Emotion Classification from EEG. In World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, June 7-12, 2015, Toronto, Canada; Jaffray, D.A., Ed.; IFMBE Proceedings; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; Vol. 51, pp. 1188–1191 ISBN 978-3-319-19386-1.

- Bhatti, A.M.; Majid, M.; Anwar, S.M.; Khan, B. Human Emotion Recognition and Analysis in Response to Audio Music Using Brain Signals. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, M.; Saeed, F.; Al-Hadhrami, T.; Ghabban, F.; Al-Sarem, M. Deep Learning-Based Approach for Emotion Recognition Using Electroencephalography (EEG) Signals Using Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM). Sensors 2022, 22, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, E.S.; El-Khoribi, R.A.; Shoman, M.E.; Wahby Shalaby, M.A. A 3D-Convolutional Neural Network Framework with Ensemble Learning Techniques for Multi-Modal Emotion Recognition. Egypt. Inform. J. 2021, 22, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddharth; Jung, T.-P.; Sejnowski, T.J. Utilizing Deep Learning Towards Multi-Modal Bio-Sensing and Vision-Based Affective Computing. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2022, 13, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Pan, J. Combining Facial Expressions and Electroencephalography to Enhance Emotion Recognition. Future Internet 2019, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G.; Yao, S.; Deng, H.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Yu, T.; Wang, K.; Peng, Y. A Multi-Modal Driver Emotion Dataset and Study: Including Facial Expressions and Synchronized Physiological Signals. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Chen, W.; Li, M. Emotion Recognition Using Cross-Modal Attention from EEG and Facial Expression. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 304, 112587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Debnath, S.; Hu, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Kweon, I.S.; Xie, S. ConvNeXt V2: Co-Designing and Scaling ConvNets with Masked Autoencoders. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023; pp. 16133–16142.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł. ukasz; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2017; Vol. 30.

- Ullah, I.; Hussain, M.; Qazi, E.-H.; Aboalsamh, H. An Automated System for Epilepsy Detection Using EEG Brain Signals Based on Deep Learning Approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 107, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhao, J. Temporal Convolutional Networks for Anomaly Detection in Time Series. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1213, 042050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripada, C.; Angstadt, M.; Kessler, D.; Phan, K.L.; Liberzon, I.; Evans, G.W.; Welsh, R.C.; Kim, P.; Swain, J.E. Volitional Regulation of Emotions Produces Distributed Alterations in Connectivity between Visual, Attention Control, and Default Networks. NeuroImage 2014, 89, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphs, R. Neural Systems for Recognizing Emotion. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002, 12, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Nashiro, K.; Yoo, H.J.; Cho, C.; Nasseri, P.; Bachman, S.L.; Porat, S.; Thayer, J.F.; Chang, C.; Lee, T.-H.; et al. Emotion Downregulation Targets Interoceptive Brain Regions While Emotion Upregulation Targets Other Affective Brain Regions. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 2973–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelstra, S.; Muhl, C.; Soleymani, M.; Jong-Seok Lee; Yazdani, A.; Ebrahimi, T.; Pun, T.; Nijholt, A.; Patras, I. DEAP: A Database for Emotion Analysis ;Using Physiological Signals. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 18–31. [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, M.; Lichtenauer, J.; Pun, T.; Pantic, M. A Multimodal Database for Affect Recognition and Implicit Tagging. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulat, A.; Tzimiropoulos, G. How Far Are We From Solving the 2D & 3D Face Alignment Problem? (And a Dataset of 230,000 3D Facial Landmarks).; 2017; pp. 1021–1030.

- Hu, X.; Chen, C.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z. Reliable, Large-Scale, and Automated Remote Sensing Mapping of Coastal Aquaculture Ponds Based on Sentinel-1/2 and Ensemble Learning Algorithms. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 293, 128740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, R.; Thagavel, P.; Thomas, J.; Fogarty, J.; Ali, F. Comprehensive Analysis of Feature Extraction Methods for Emotion Recognition from Multichannel EEG Recordings. Sensors 2023, 23, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Liang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Huang, W.; Cai, Z.; Ye, Y.; Qiu, L.; Pan, J. MindLink-Eumpy: An Open-Source Python Toolbox for Multimodal Emotion Recognition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 621493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Qin, T.; Zheng, Q. EEG-Based Emotion Recognition With Emotion Localization via Hierarchical Self-Attention. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2023, 14, 2458–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).