1. Introduction

Emotion is a complex state influenced by various feelings, behaviors, and thoughts when the human brain is stimulated[

1]. It plays a crucial role in shaping our mental states and guiding behavioral decisions. The advancement of emotion recognition systems has become a prominent focus across disciplines such as psychology, artificial intelligence, computer vision, consumer behavior analysis, and medical treatment[

2].

Understanding human emotions is a complex task that involves analyzing both non-physiological and physiological signals. Facial expressions, voice tone, and text messages are some of the non-physiological signals we use to decipher someone’s emotions[

3,

4]. On the other hand, physiological signals like brain activity, muscle movements, and skin responses provide a deeper insight into our emotional state[

5]. People can mask their true emotions, making it tricky to accurately predict how their emotions solely based on non-physiological signals they emit. In contrast, physiological signals like EEG offer a more reliable glimpse into someone’s emotions. EEG stands out as a star performer in capturing emotions in real-time with high precision and at a reasonable cost. It has become a go-to method for reading emotions without invading someone’s privacy[

6,

7,

8].

In the early stages of EEG emotion recognition research, scholars focused on traditional EEG features and used algorithms like Support Vector Machines(SVM) and K-nearest neighbors(KNN)[

9,

10]. However, manual feature selection in machine learning is time-consuming and laborious, and the accuracy is not ideal. With the advancement of technology, deep learning has become a new solution for EEG emotion recognition, demonstrating superior performance in identifying human emotions[

11,

12,

13]. Various models including convolutional neural networks(CNN)[

14], capsule networks(CapsNet)[

15], and long short-term memory networks(LSTM) [

16]have been developed by researchers to comprehend human emotions through EEG signals. For instance, Huang et al. [

17] devised an S-EEGNet model achieving an accuracy of 89.91% and 88.31% on the DEAP dataset. In a separate study, Zheng and colleagues[

18] introduced a CNNFF architecture with an average classification accuracy of 93.61% for valence and 94.04% for arousal respectively. Although the above studies have achieved good results, they do not provide further results. Zheng et al. [

19] trained a DBN to analyze differential entropy features across multiple EEG channels, comparing deep and shallow models using the SEED dataset with an average accuracy of 86.08%, 83.99%, 82.70%, and 72.60% in DBN, SVM, LR, and KNN, respectively. Cui and his team [

20] developed a new model called RACNN for classifying emotions in EEG data, achieving over 95% identification accuracy on both valence and arousal classification tasks using DEAP and DREAMER datasets. However, these methods only use a single network model, and the recognition accuracy needs to be improved. To further improve the accuracy of EEG emotion recognition, researchers have been experimenting with hybrid network models that combine techniques like CNN, RNN, LSTM, GCNN, and attention mechanisms in innovative ways. Zong et al. [

21]introduced the FCAN-XGBoost algorithm which blends FCAN and XGBoost algorithms for processing DEAP and dream data sets with accuracies of 95.26% and 94.05%, respectively. Chakravarthi et al. [

22] developed an automated system using a combination of CNN and LSTM based on the ResNet-152 algorithm achieving an impressive accuracy of 98%.

The aforementioned methods have yielded a series of satisfactory results. However, the sheer volume of irrelevant information present in EEG signals means that analyzing them requires a lot of computational power[

23]. Cutting through this noise to uncover the true emotional cues is a challenge that researchers are striving to overcome. Also, the current methods for extracting features often result in a significant loss of important information [

22], presenting a pressing issue that needs to be addressed promptly.

To address the aforementioned issues, a two-flow adaptive convolutional cyclic mixing network (CSA-SA-CRTNN) combined with an attention mechanism is proposed for emotion recognition in EEG. The model initially utilizes the CSAM module to assign weights to EEG channels and then inputs the EEG signals into the two-stream adaptive convolutional circulation network to extract local spatiotemporal features. Subsequently, the local features extracted from the two-stream network are spliced and inputted into the time-series Convolutional network combined with a multi-head self-attention mechanism (MHSA-TCN) to extract global information. Finally, the feature vectors are fed into the fully connected layer, and a softmax classifier is employed for emotion classification.

In summary, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

A novel approach has been developed for attending to various brain signals, referred to as the channel-wise attention module (CSAM). This module function selectively highlights the most pertinent aspects of the signal while disregarding extraneous information that is inconsequential about emotions. This facilitates more efficient cognitive processing, conserving time and energy resources while ensuring focused attention on critical informational components.

A multi-head self-attention mechanism (MHSA) has been developed and integrated with CRNN and TCN to effectively capture both local and global key features in emotional data. This innovative technique significantly enhances our model’s capacity for accurate emotion recognition, while also reducing computational complexity.

An adaptive convolutional recurrent network (SA-CRNN) is proposed for extracting local EEG information. This network can adaptively match appropriate convolutional stride and pooling parameters for the provided convolutional kernel size, effectively addressing the issue of information loss and improving the final recognition performance.

A dual-stream adaptive convolutional recurrent hybrid network with an attention mechanism (CSA-SA-CRTNN) is designed for emotion recognition.

2. Related Work

This section introduces the relevant knowledge and research in the field of EEG emotion recognition from three aspects: emotion model, feature fusion and mixing model, and attention mechanism.

2.1. Emotional Model

Researchers studying emotion recognition use two models to describe emotions: the Discrete Model[

24,

25] and the Dimensional Model[

26,

27]. The Discrete Model sees emotions as distinct points and believes that emotions are made up of basic emotions. Although the Discrete Model is straightforward to understand, it falls short in describing the complexity of human emotions. The Dimensional Model tries to understand human emotions by mapping them in a two- or three-dimensional space. The Valence-Arousal Model is the most classic dimensional model, which represents different emotions as points on a two-dimensional plane of Valence and Arousal. Other emotions are made up of different combinations of Valence and Arousal[

28]. The Dimensional Emotional Model is continuous and can express emotions across a wide range.

2.2. Feature Fusion and Hybrid Models

Recent studies[

29,

30] have revealed that combining multiple EEG features leads to superior results in detecting emotions compared to using just one feature. In the field of emotion recognition research using deep learning methods, feature fusion is often closely associated with the development of hybrid models[

31,

32,

33]. For example, Feng et al.[

34] proposed a new model called ST-GCLSTM, which combines SGCN and attention-enhanced bidirectional LSTM. This model can obtain the temporal patterns of brain signals and capture the different intensities of these signals at different times, achieving a recognition accuracy of 95.52%. Li et al.[

35] proposed a BLSTM network model based on multimodal attention, which can learn the optimal temporal features of EEG signals with a recognition accuracy of 81.3%. Overall, hybrid network models incorporating CNN, RNN, LSTM, GCNN, and attention mechanisms tend to yield good results in emotion recognition tasks.

2.3. Attention Mechanism

Humans have the remarkable ability to focus on specific elements of a scene while filtering out other distractions – a phenomenon known as the attention mechanism. In recent years, the integration of neural networks with attention mechanisms has revolutionized the field of emotion recognition, particularly in EEG-based applications[

34,

36]. By selectively filtering and enhancing crucial components of the input data, these attention mechanisms have significantly boosted the accuracy of emotion recognition systems. Researchers like Zhang et al. [

36]have developed innovative deep-learning models that leverage attention mechanisms to extract key features from EEG signals, yielding impressive classification results in emotion recognition tasks, and the classification accuracy reaches 92.47%. Similarly, Lew et al. [

37]have explored the use of attention mechanisms in conjunction with adversarial networks to capture complex spatiotemporal relationships within EEG data, ultimately mitigating domain shift issues, and the classification accuracy reaches 98.15%.

3. Methodology

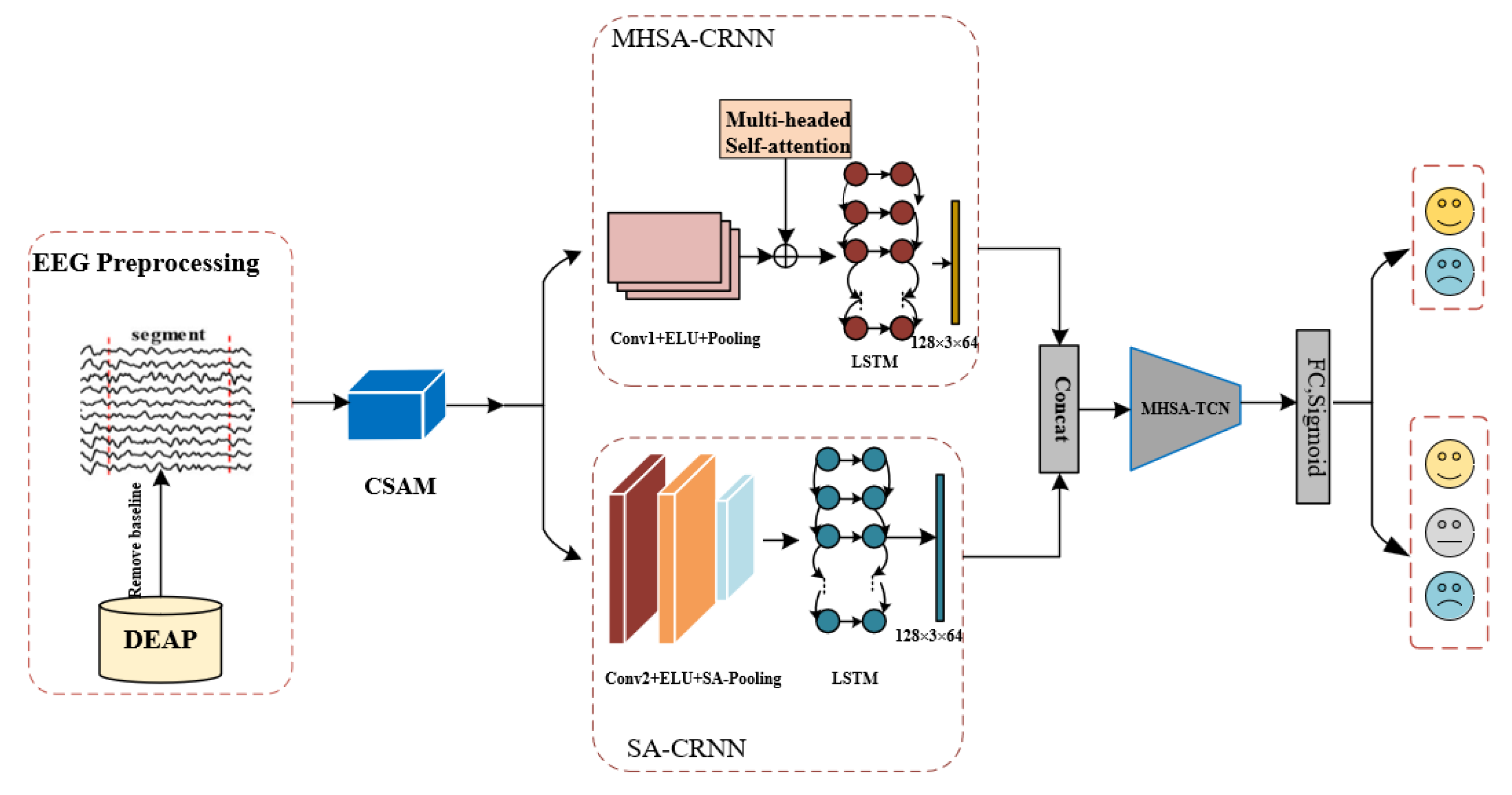

The proposed CSA-SA-CRTNN model’s framework and process are displayed in

Figure 1, which consists of four modules: CSAM, SA-CRNN, MHSA-CRNN, and MHSA-TCN. The CSAM assigns weights to EEG channels, while the dual-stream convolutional recurrent framework composed of SA-CRNN and MHSA-CRNN extracts local EEG features. The MHSA-TCN module extracts global EEG features, and the feature vectors are fed into the softmax classifier for emotion classification. In the following chapters, we will explain the model’s framework and process in detail.

3.1. CSAM

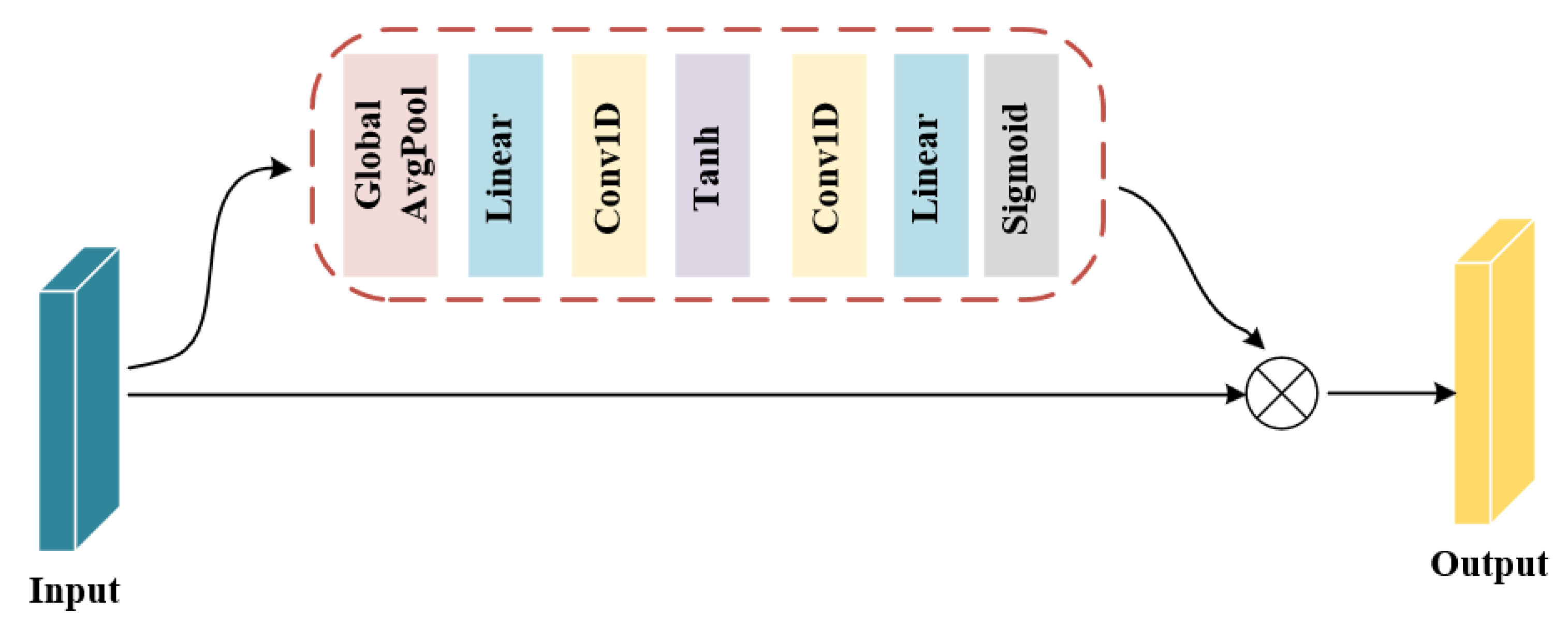

Inspired by[

38], a new channel attention mechanism (CSAM) has been introduced. It receives preprocessed EEG signals, allocates attention to channel dimensions, and enhances the effect of attention mechanisms on improving model performance. The proposed CSAM module can be found in

Figure 2.

The module comprises a global pooling layer, linear layer, convolution layer, and activation layer. It allocates weights to the channel dimension, enhancing important information and minimizing unimportant information, thereby improving the ability to recognize and classify emotions while reducing computing costs.

Table 1 shows the specific parameter settings for this module.

3.2. MHSA-CRNN

MHSA-CRNN comprises a Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network (CRNN) and a Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) mechanism. It is capable of effectively extracting critical spatio-temporal features at a local level.

3.2.1. CRNN

CRNN is the basic framework of the MHSA-CRNN module. To reduce the computational complexity of the model, a three-layer CNN and a two-layer LSTM are used here.

This module first uses CNN to extract spatial dimension information and then adopts LSTM to extract the temporal dependency of the signal, as shown in equation (1):

Here, is the input signal, andis the feature vector output through the CRNN network.

CNN consists of different layers, including a convolutional layer, an activation layer using exponential linear units (ELUs), and a maximum pooling layer. In the activation after convolution, the ELU function is preferred over the commonly used ReLU function. The kernel size and step size of the convolution operation are set to (32,40) and 1, respectively, using the same Settings as in the literature [

38]. The pooling layer uses a kernel size of (1,75) with a stride length of 10. Next comes the LSTM model, which consists of two stacked layers. Each layer of the LSTM receives hidden states as input from the previous layer to learn more advanced feature representations in the data. While adding more layers can improve a model’s performance, it also increases training time and computational requirements. The input dimension of the LSTM unit is set to 80 and the hidden layer dimension to 64.

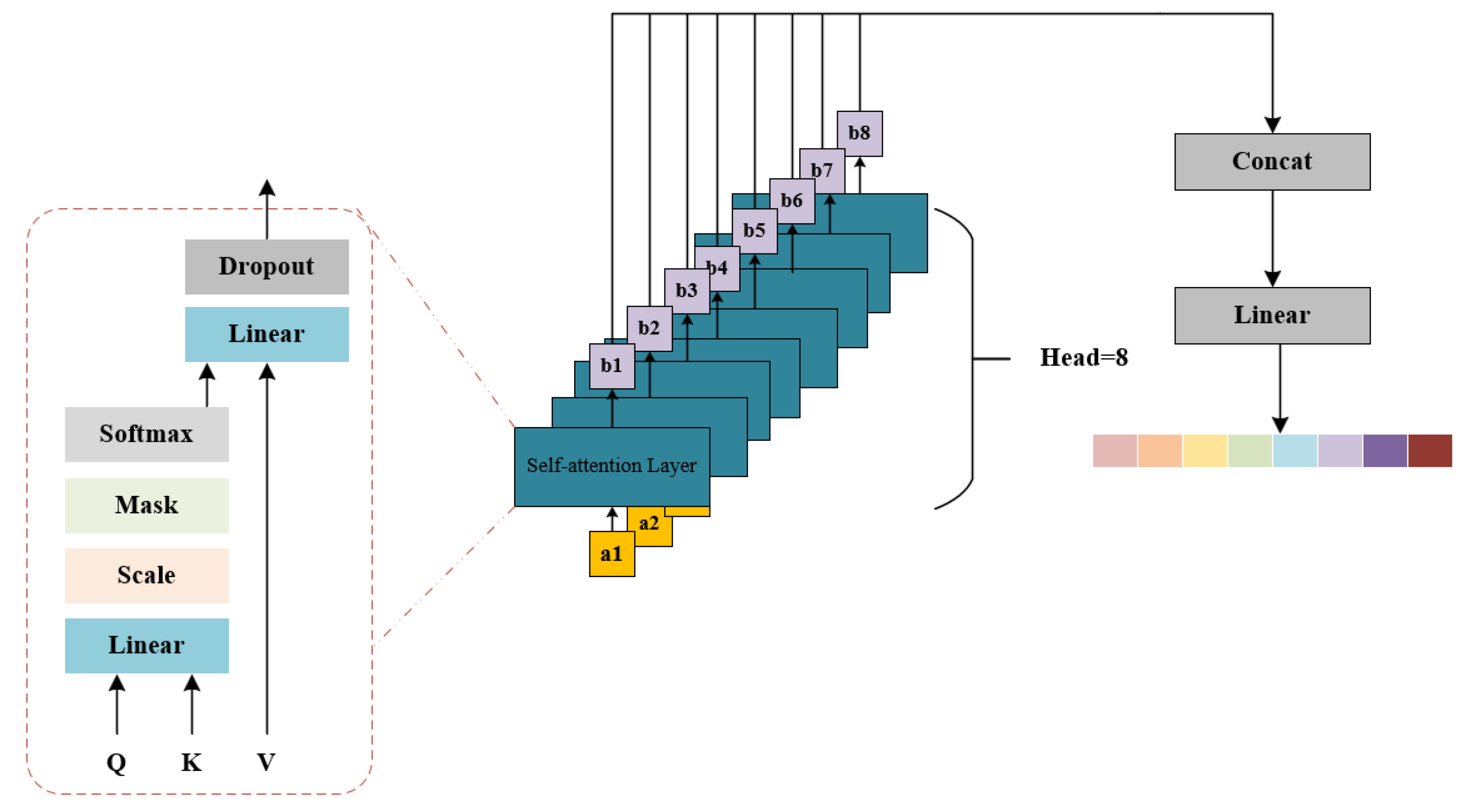

3.2.2. Multi-Headed Self-Attention (MHSA)

To better understand contextual information and further improve model performance, we developed a novel multi-head self-attention mechanism, MHSA, and integrated it into CRNN to automatically capture dependencies among sequences and enhance the representation ability of the network. The structure of MHSA is shown in

Figure 3.

The MHSA model utilizes multiple sets of query, key, and value mappings to concurrently compute several attention representations. These representations are then linearly stacked to produce the final multi-head attention representation. This approach allows the model to focus on different aspects of the input sequence, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to generalize.

In this paper, the Head of MHSA is equal to 8, and the overall calculation process is as follows:

Here, represents the self-attention output, is the scaling factor, are the query, key and value transformation matrix of the head respectively, represents the head attention output, is the final output of MHSA, and represents the transformation matrix of the output.

The self-attention mechanism acts as the central processing unit of the Multi-Head Attention (MHSA) algorithm, ensuring seamless operation. Initially, input features undergo linear transformations to yield query (Q), key (K), and value (V) features. These transformed features are then partitioned into three groups: Q, K, and V. The attention scores are computed by multiplying the query and key together and incorporating a scaling factor (Scale). Subsequently, these scores are adjusted based on an input mask to filter out irrelevant information. Following this, the attention scores undergo a Softmax function for normalization purposes. Ultimately, the output is generated by combining values with attention scores. This output then undergoes further transformation to revert to its original form, along with some Dropout processing for additional fine-tuning.

3.3. SA-CRNN

The structure of the Self-Adaptive Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network (SA-CRNN) is similar to the CRNN described in

Section 3.2.1, with the difference being that its corresponding convolutional stride, pooling kernel size, and pooling stride can be adaptively adjusted based on the given convolutional kernel. This structural design aims to fully extract EEG emotional information and avoid the loss of feature information due to fixed parameter settings. The calculation methods for the convolutional stride and pooling layer parameters of the convolution operation in this module are as follows:

Where is the convolutional stride, [-1] is the element of the last dimension of the convolutional kernel, is the size of the pooling kernel, and is the pooling stride. In this module, the input dimension of the LSTM unit is 720, and the hidden layer dimension is 64.

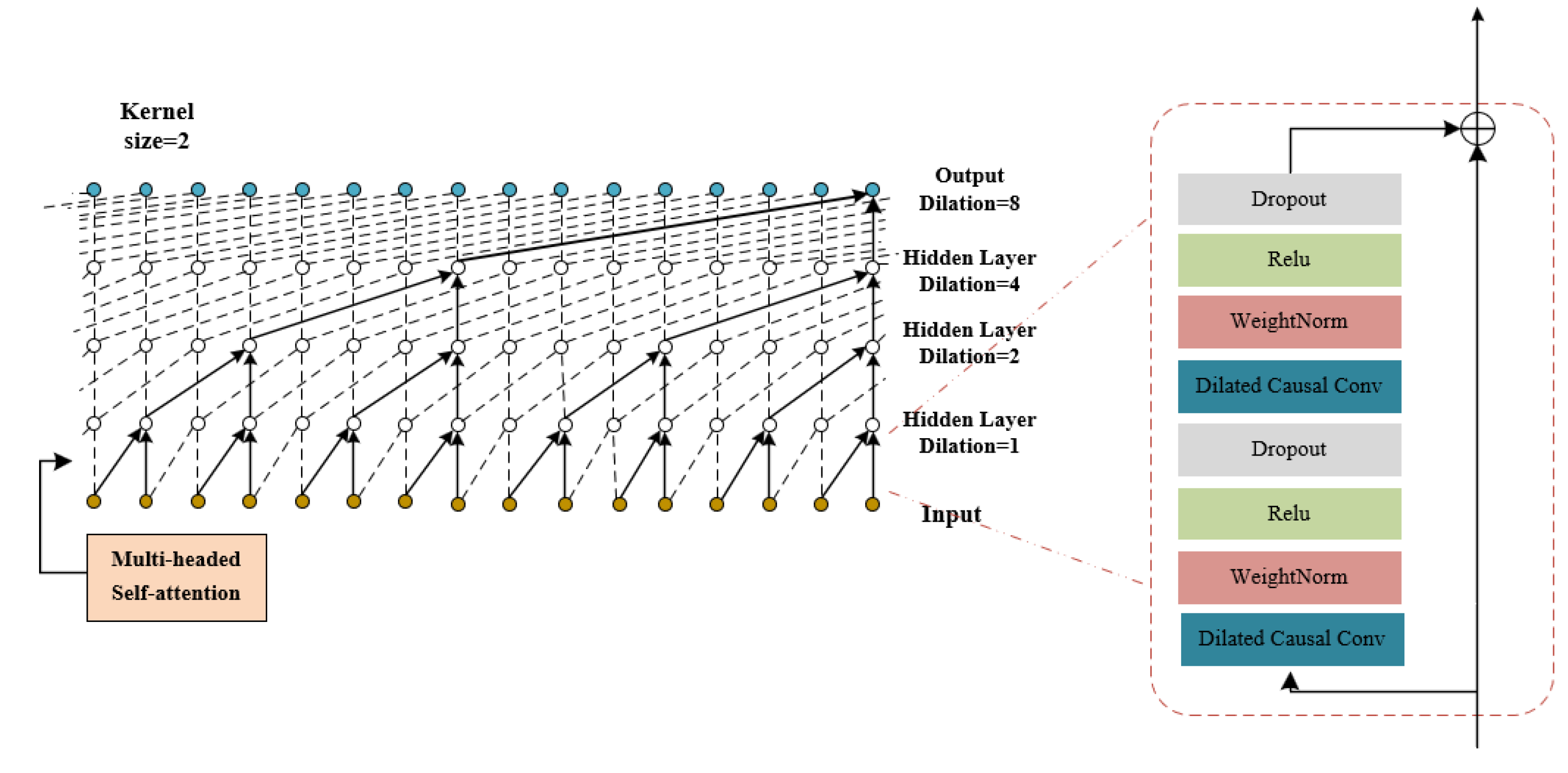

3.4. MHSA-TCN

A common way to understand time-dependent problems is to use recurrent neural networks (RNNS). However, RNNS also has its disadvantages, such as difficulty in parallelizing calculations, low processing efficiency, and the risk of gradient explosion and gradient disappearance. To address these challenges, Bai S and their team [

39] introduced temporal convolutional networks (TCN). TCN uses one-dimensional convolution, extended convolution, causal convolution, and residual convolution to maximize the ability of convolution to analyze time series. This approach is superior to LSTM (a type of RNN) in many different tasks.

TCN is a technology that enables efficient parallel computing and is well-suited for processing large amounts of data. Its benefits include the ability to extract features of different scales by stacking multiple convolutional layers, accurately capturing local dependencies in sequence data by increasing the receptive field of the convolutional kernel and avoiding issues with gradient vanishing and explosion, etc. The main reason why TCN is so useful is that it significantly increases the receptive field[

40]. The calculation method of the receptive field for the

layer is as follows:

Where is the receptive field of the layer, is the size of the convolutional kernel, is the number of convolutional layers in each residual block, and is the dilation factor of the layer.

To make the network work better, we’ve added a complex feature called multi-head self-attention mechanism (MHSA) that we talked about in

Section 3.2.2 to TCN. Look at

Figure 4 to see how MHSA-TCN is structured.

This network takes the local features it already got from MHSA-CRNN and SA-CRNN to find global EEG features. In this experiment, TCN consists of four hidden layers, with each hidden layer having 25 channels, the kernel size =2, and dilation factors of d= [

1,

2,

4,

8].

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

The DEAP dataset [

41], also known as the Database for Emotion Analysis using Physiological Signals, is a comprehensive collection of data utilized by researchers to gain a deeper understanding of emotions. This dataset was compiled by researchers at the Queen Mary University of London and encompasses various physiological signals from the body and brain of 32 individuals, consisting of an equal number of male and female participants with an average age of 26 years. Additionally, videos capturing the facial expressions of 22 participants were recorded to observe their reactions. The research involved having the participants watch short music videos and evaluate their emotional responses. Parameters such as arousal level, valence, liking or disliking, dominance, and familiarity were measured using the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) scale. Notably, each participant viewed 40 different videos in real-time to ensure the accuracy of data collection. The ratings were based on a two-dimensional arousal-valence model rated on a scale from 1 to 9. The DEAP dataset includes 32 channels of EEG signals and 8 channels of peripheral physiological signals, all recorded at a rate of 512 Hz.

For this experiment, we decided to focus solely on the EEG signals for emotion recognition, ditching the peripheral data. The experimental data within the DEAP dataset is split into 32 separate files, each representing an individual experimental subject. Within each participant’s file, you can find two arrays of data, which, after some basic preprocessing are shown in

Table 2.

4.2. Data Preprocessing and Emotional Label Processing

Data preprocessing is a necessary process for EEG-based emotion recognition. In this paper, we first downsampled the signals to 128Hz. Then, the 63-second data was segmented into 1-second windows, and the arithmetic mean of the first three 1-second baseline segments was calculated. Subsequently, the mean baseline was subtracted from each of the remaining 60 segments to remove the baseline. The calculation process is as follows:

Where represents the average baseline signal, is the original EEG signal, and represents the signal after baseline removal. Finally, the 60 1-second segments after baseline removal are rearranged in chronological order into 3-second segments as input for the model.

Similar to the literature [

42], this experiment adopts two schemes based on the valence dimension and arousal dimension for the processing of emotional labels. The first uses 5 as the threshold, arousal and valence SAM scores 1-5 are classified as low scores, 6-9 as high scores, low (LA) and high (HA) in the arousal dimension, and low (LV) and high (HV) in the valence dimension. In the second scheme, 4 and 6 were used as thresholds. Arousal and valence SAM scores of 1-4 were classified as low scores, 5-6 as medium scores, 7-9 as high scores, low (LA), medium arousal (MA), and high (HA) in arousal dimension, and low (LV), medium valence (MV), and high (HV) in valence dimension. The specific division of the two schemes is shown in

Table 3.

4.3. Experimental Setup

The DEAP public dataset was utilized to train and validate the model on a powerful GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPU using the Pytorch framework in the research. The model was optimized using Adam as the optimizer, with a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 128, and a cross-entropy loss function. The experiment ran for 30 epochs to fine-tune the model. The data was split into a training set and a test set in an 8:2 ratio to ensure robust evaluation. To further evaluate our model’s performance, a rigorous 10-fold cross-validation approach was employed.

5. Results and Discussion

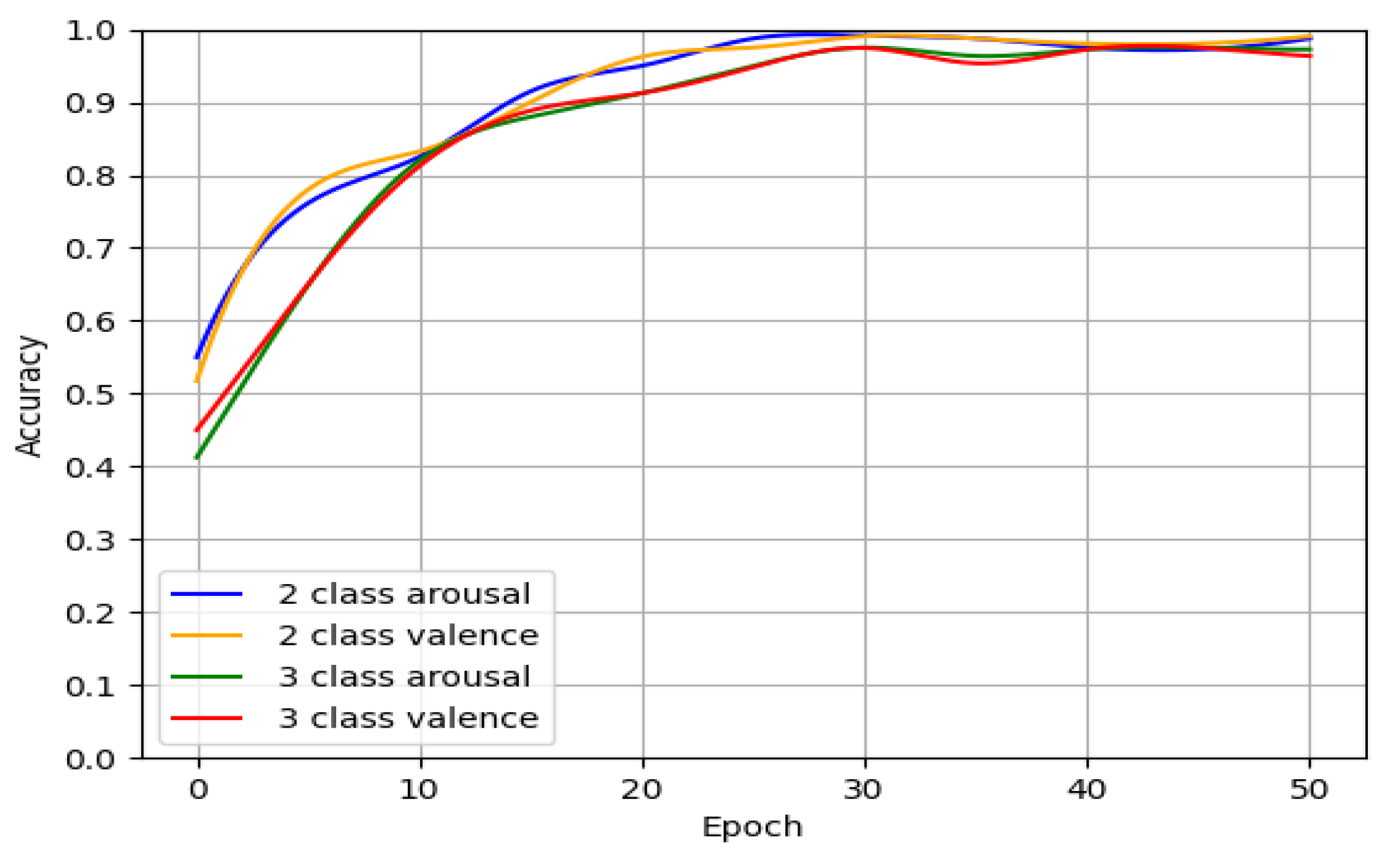

5.1. Convergence of the Model

Figure 5 illustrates the fluctuating pattern of accuracy in binary and triple classification across the DEAP dataset during training. As the process unfolds, the accuracy experiences a steady increase before eventually stabilizing at a consistent level, highlighting the model’s strong convergence after a certain number of iterations. Notably, the data suggests that the model reaches its peak performance at around 30 iterations, demonstrating remarkable accuracy while utilizing minimal resources. Consequently, for this experiment, an epoch of 30 is considered ideal for optimal results.

5.2. Overall Performance

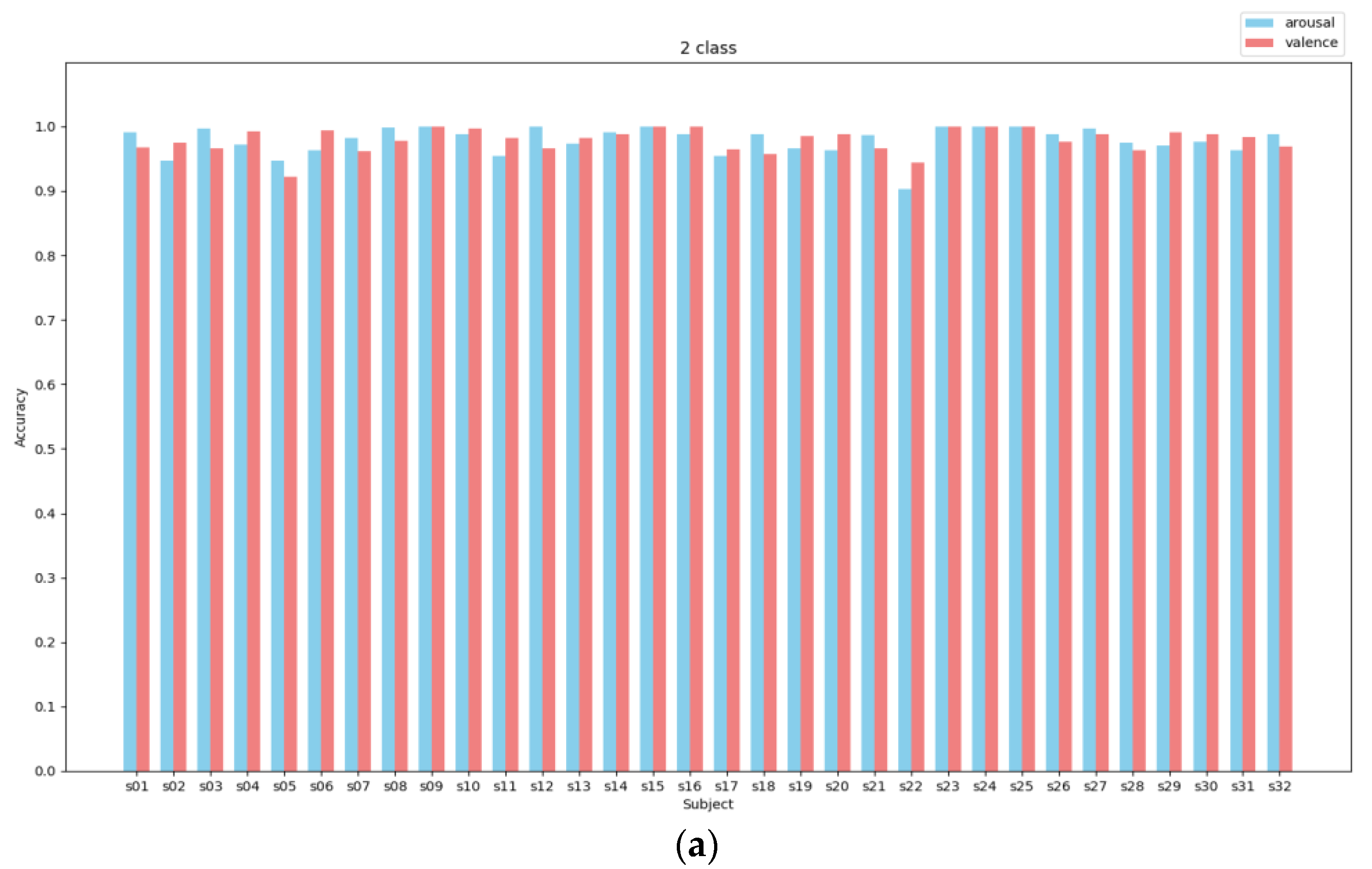

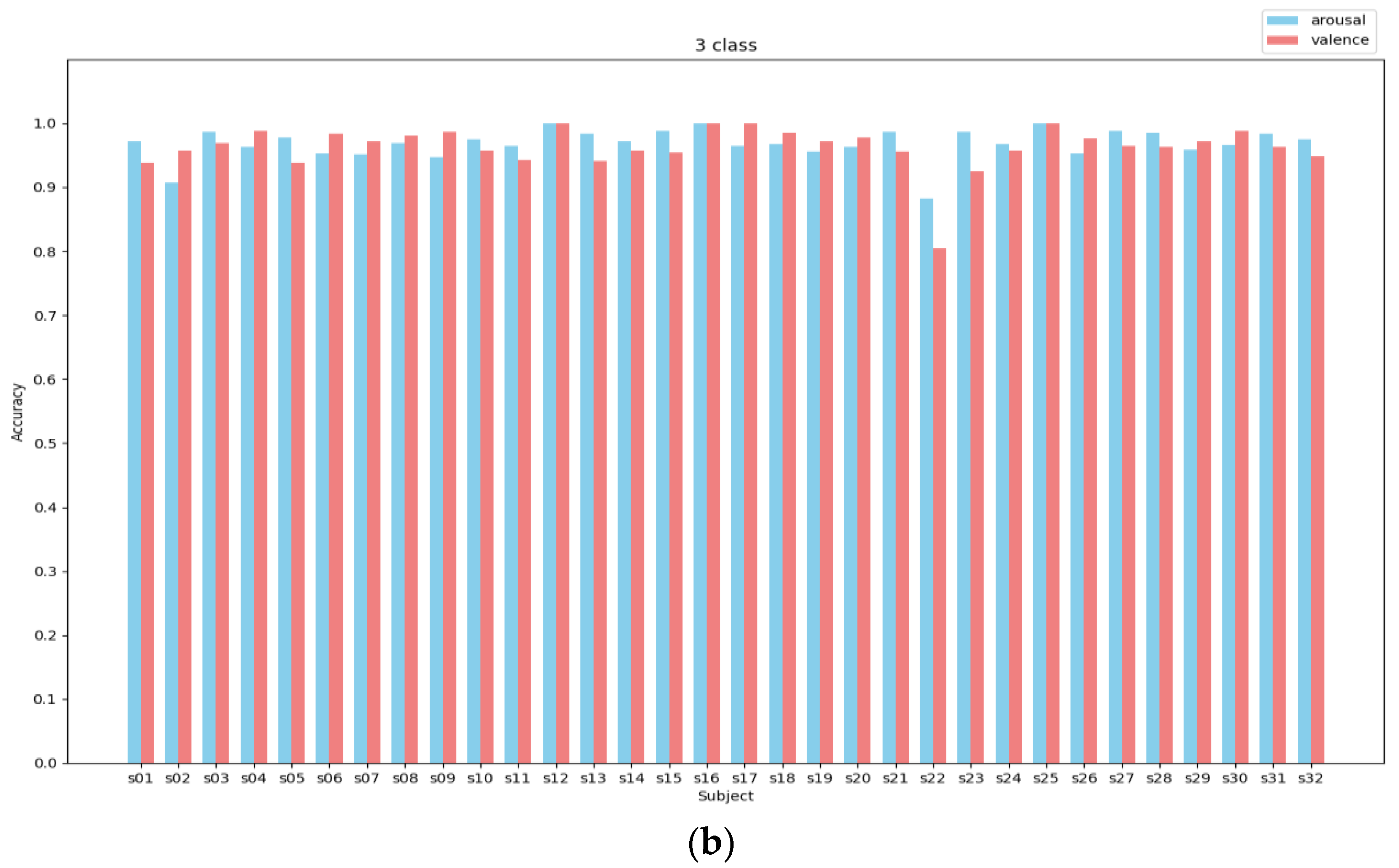

In

Figure 5, it is evident that the CSA-SA-CRTNN model is reliable and Effective when used on the DEAP dataset. Moving on to

Figure 6, we can observe the accuracy of the model on individual subjects within the DEAP dataset, especially when the epoch is finely tuned to the ideal 30.

In the binary experiment, the average accuracy for the valence dimension reached 99.15%, with the exceptions of s05 and s22, while for the arousal dimension, it reached 99.26%, except for s02 and s22. In the ternary classification experiment, the average accuracy of the valence dimension was 98.05% (except for s05 and s22), and in the arousal dimension, it was 97.69% (except for s02 and s22). It is noteworthy that subject No. 22 exhibited consistent characteristics in both two-category and three-category experiments, with significantly lower recognition accuracy compared to other subjects - achieving 90.27% and 93.75% in two-category valence and arousal, as well as 87.40% in three-category valence; whereas arousal achieved only 80.75% in three-category. This could be attributed to the possibility that the participants were distracted during the experiment or due to their subjective biases in scoring.

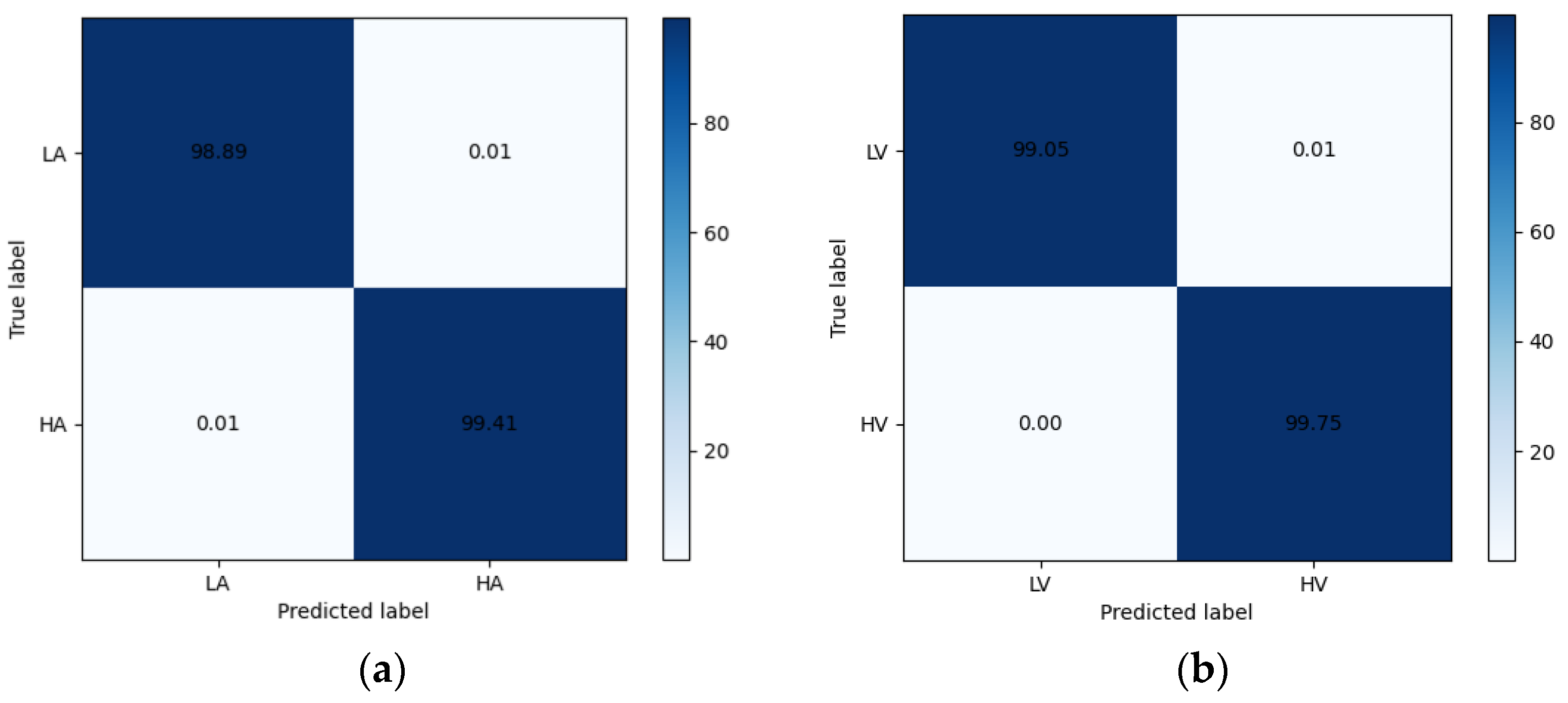

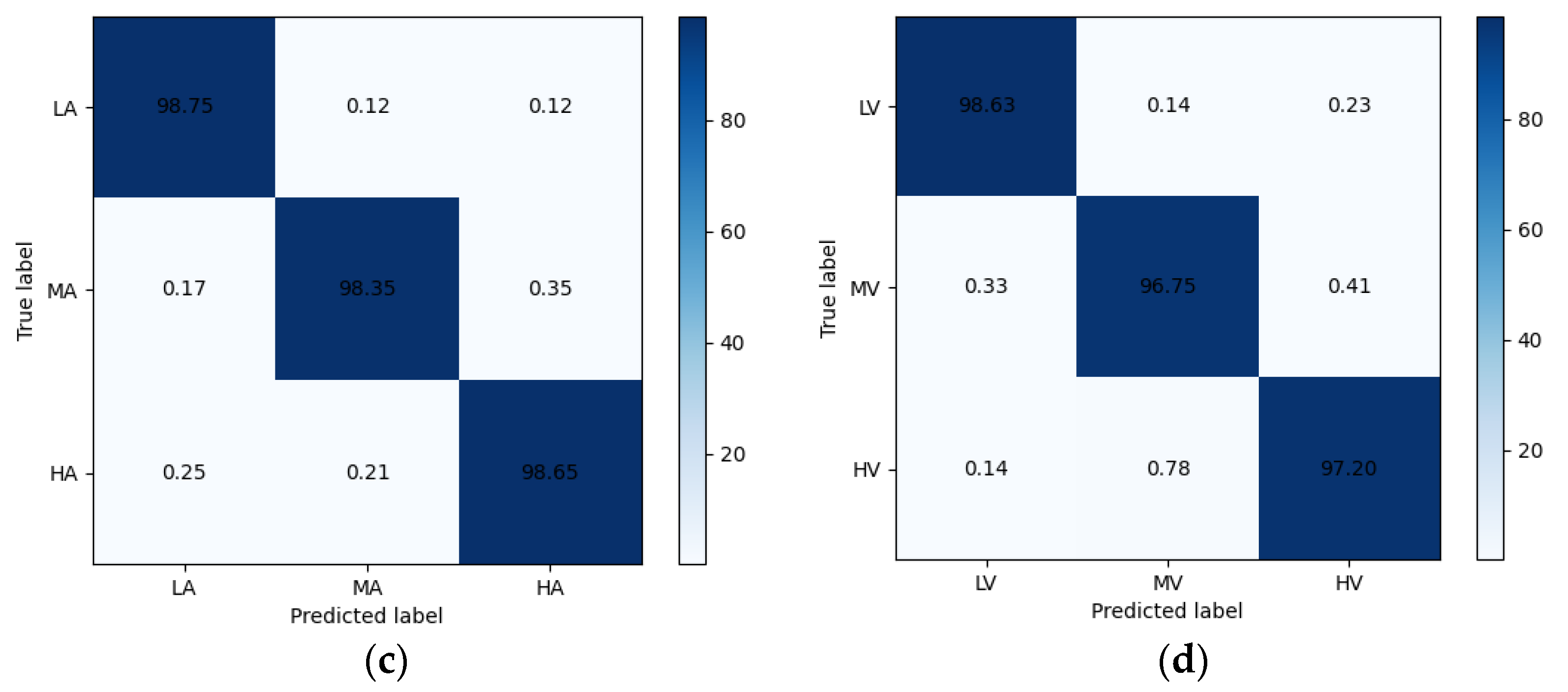

The confusion matrix is shown in

Figure 7. The confusion matrix shows the excellent classification ability of CSA-SA-CRTNN for each emotion category.

5.3. Comparison with Related Research

To further evaluate the effectiveness of the model, we compared CSA-SA-CRTNN with previous studies on EEG-based emotional recognition using the DEAP dataset. Our comparison methods are outlined below:

Tsception (Yi et al,2021)[

43]: Tsception is a cutting-edge Deep learning model that can analyze EEG signals in a way that mimics the complexities of the human brain. It uses a dynamic temporal layer that can adapt to different time scales and frequencies present in EEG signals. Additionally, Tsception has an asymmetric spatial layer that takes into account the asymmetrical neural activations associated with emotional responses. This layer can pick up on subtle differences in how the brain processes information, allowing it to create a more accurate representation of the data it receives. Finally, Tsception has a fusion layer that brings together all the information.

DCRNN (Li et al,2022)[

44]: DCRNN sifts through EEG signals, using a deep sparse autoencoder network (DSAE). Its mission is to cut through the noise and reconstruct the underlying features of EEG signals. By teaming up a convolutional neural network (CNN) with long short-term memory (LSTM), DCRNN digs deep into the connections between different parts of the brain and integrates contextual information from EEG signal frames.

4D-CRNN(Shen et al,2020) [

45]: The 4D-CRNN is a groundbreaking technique that takes complex features from various sources and transforms them into an intricate, four-dimensional framework. It operates by leveraging the powers of both the convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. The CNN delves into the frequencies and spatial intricacies of each slice within the 4D input, while the LSTM uncovers the temporal relationships hidden within the CNN’s findings. The fusion of these two powerful networks results in a model that can truly understand and make sense of the intricate connections within the data.

BiSMSM(Li et al,2023) [

46]: BiSMSM is a complex framework that delves into the intricacies of time and space. It consists of two streams, one focusing on spatial aspects and the other on temporal aspects. Designed to decipher information from various viewpoints including time, space, locality, and globality, this framework is made up of interconnected modules. The spatial and temporal streams mirror each other in structure, featuring a module centered around a multilayer perceptron (MLP). This module is key in unraveling both intra- and inter-channel insights from specific regions. Additionally, a self-attention mechanism module is in place to extract the global signal correlations.

AP-CapsNet(Liu et al,2023) [

47]: The AP-CapsNet method combines coordinated attention to help understand where things are about each other in the input data, and then transforms this information into a complex space to identify emotions. To achieve this, a pre-trained model is utilized to extract features, and a double-layer capsule network is built for in-depth analysis.

ATDD-LSTM(Du et al,2021)[

48]: The ATDD-LSTM model functions as a mechanism to focus on specific segments of information produced by the LSTM to gain a deeper understanding of emotions. Additionally, it incorporates a domain discriminator to ensure consistency of information across diverse contexts.

ICaps-ResLSTM(Fan et al,2024)[

49]: ICaps-ResLSTM can understand the different patterns and locations within EEG data using capsule networks. And get this - it also has a ResLSTM module that helps it learn even more detailed and complex features by connecting different modules in time and space. This means it can pick up on even the most subtle differences in EEG data, making it good at distinguishing between different brain activities.

CADD-DCCNN(Li et al,2024)[

50]: To gain a deeper understanding of the emotions captured in EEG signals, utilizing DE features obtained through STFT. Each DE feature channel provides a unique perspective and employs an attention mechanism to extract key emotional data across the EEG timeline. CADD-DCCNN explores intricate interconnections among diverse timeframes, enhancing the comprehension of nonlinear relationships. Additionally, CADD-DCCNN incorporates a domain discriminator to ensure consistency in data representation and bridge gaps among different sources.

Table 4 presents a comparison of the outcomes yielded by these approaches. As shown in the table, the accuracy of CSA-SA-CRTNN on the DEAP dataset is 99.26% and 99.15%, respectively. Compared with existing methods, our model has achieved more competitive results.

5.4. Ablation Study

The proposed model consists of four modules: the CSAM module, the SA-CRNN module, the MHSA-CRNN module, and the MHSA-TCN module. To evaluate the contribution of each module in the model, we conducted four types of ablation experiments on the DEAP dataset.

Specifically, four ablation models were constructed: SA-CRTNN, CSA-CRTNN, CA-SA-CRTNN, and CSA-SA-CRNN. Among them, SA-CRTNN is the model that abandons the CSAM module. CSA-CRTNN is the model without the SA-CRNN module. CA-SA-CRTNN is a model excluding the MHSA-CRNN module. CSA-SA-CRNN is a model that removes the MHSA-TCN module, and the detailed composition of each model is shown in

Table 5.

Each model was tested on the DEAP dataset for binary and ternary classification experiments, and the results are shown in

Table 6. Currently, our proposed model achieves the best accuracy, with 99.26% and 99.15% for binary classification and 97.69% and 98.05% for ternary classification, respectively. Compared to the proposed model, SA-CRTNN has the largest decrease in accuracy, with 13.01% and 14.15% for binary classification and 13.95% and 19.30% for ternary classification, respectively. This indicates that the proposed channel attention module CSAM plays a crucial role in the model. Without CSAM, the model may focus on some useless information, leading to a decrease in accuracy. CSA-CRTNN has the second largest gap in accuracy compared to the proposed model, with 6.76% and 4.16% for binary classification and 3.94% and 11.80% for ternary classification, respectively. This suggests that the proposed SA-CRNN module can effectively address the issue of information omission during feature extraction. CSA-SA-CRNN ranks third in terms of accuracy gap with the proposed model, with 4.47% and 6.24% for binary classification and larger gaps of 10.61% and 9.51% for ternary classification, respectively. This underscores the necessity of global feature extraction. CA-SA-CRTNN has the smallest decrease in accuracy, with 2.11% and 2.90% for binary classification and 1.15% and 3.06% for ternary classification, this indicates that MHSA-CRNN has a certain contribution in the model.

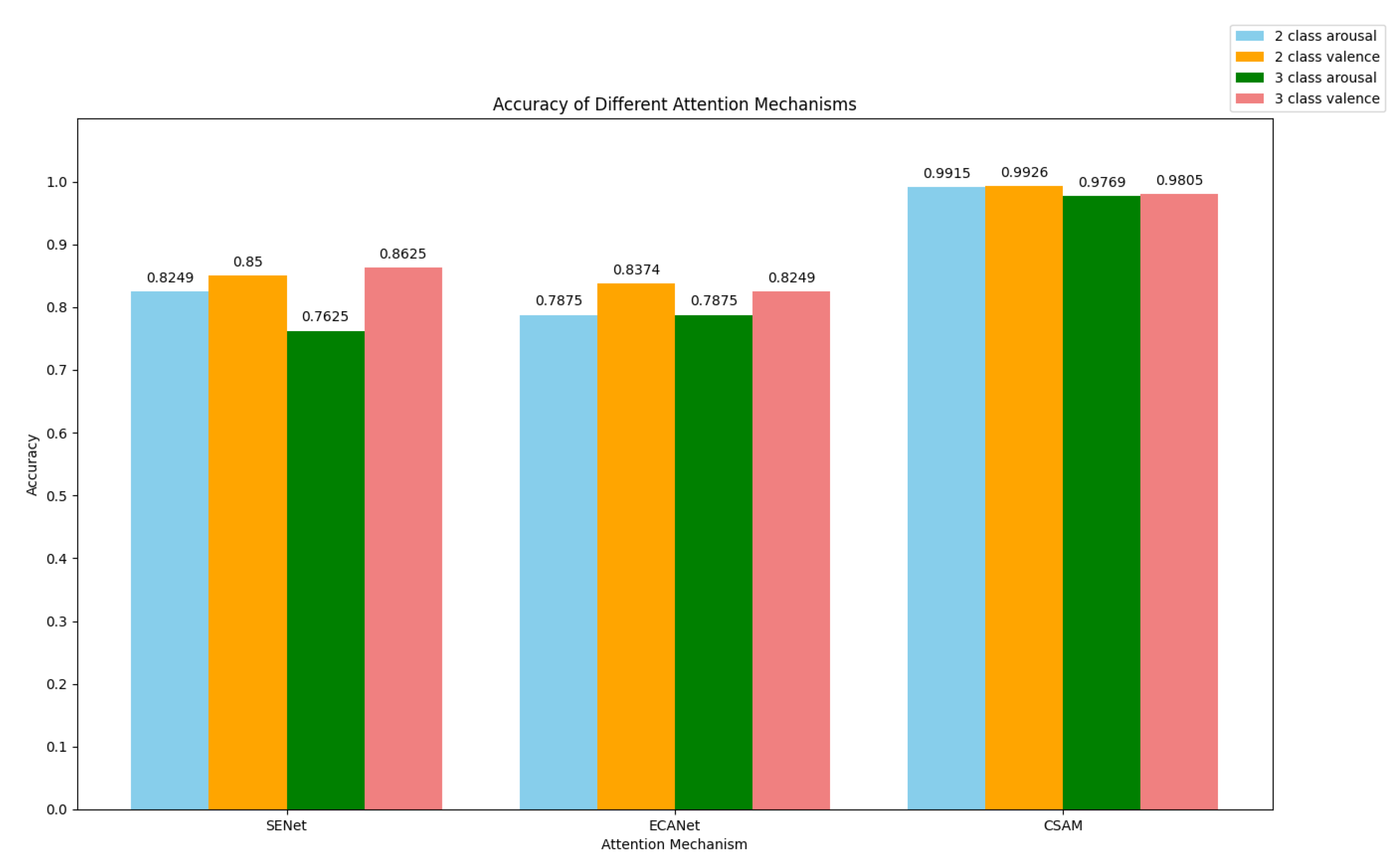

5.5. CSAM Compared with Other Channel Attention Mechanism

To validate the efficacy of the channel attention mechanism proposed in this paper, we conducted a comparative analysis with the commonly used mechanisms SENet and ECANet. The results are depicted in

Figure 8.

SENet [

51]gives each feature channel in a feature map a weight value. The network can concentrate on certain characteristics since the squeeze and excitation procedures automatically determine the significance of each channel. This method aids in enhancing the network’s performance across a range of jobs.

The ECANet neural network architecture[

52] eliminates the requirement for fully connected layers by using 1x1 convolutional layers after the global average pooling layer. This method helps to prevent size reduction. In addition, the design achieves cross channel information exchange by using dimensional convolution. The size of the convolutional kernel is adaptive, which means that layers with many channels can interact more across channels.

Based on the experimental results, it has been found that the channel attention mechanism, CSAM, proposed in this paper, outperforms SENet and ECANet. This suggests that in our model, CSAM can more accurately identify the important channels of EEG signals in comparison to other commonly used channel attention mechanisms. Consequently, this leads to an improvement in the recognition accuracy of the model.

5.6. Evaluation of Model Efficiency

The primary objective of this paper is to enhance model accuracy while simultaneously reducing computational costs. To illustrate the capability of CSA-SA-CRTNN in reducing the computational burden of the model, we have presented the parameters of the proposed model in

Table 7 and compared them with those of four other models in

Table 8. The findings indicate that our model exhibits higher efficiency, with model parameters totaling 2.90M. This outcome suggests that the model can achieve superior accuracy while consuming fewer resources.

6. Conclusion

In this work, we introduce CSA-SA-CRTNN, a novel model for emotion recognition. To increase accuracy, our model is made to extract pertinent data from several viewpoints, such as temporal, Spatial, local, and global. The CSAM channel attention module is introduced to improve the classification performance by assigning varying weights to distinct channels. Additionally, we introduce SA-CRNN, an adaptive convolutional recurrent module that tackles the problem of missing information during feature extraction. To extract local and global information, we also integrate CRNN and TCN with the multi-head self-attention mechanism, MHSA. We conducted binary and ternary classification experiments on the DEAP dataset, achieving 99.26% and 99.15% accuracy for arousal and valence in binary classification, and 97.69% and 98.05% in ternary classification, demonstrating the effectiveness of our model. Furthermore, our model is efficient, achieving the highest accuracy with lower computational costs than other models. In future work, we plan to explore the performance of our model on different datasets and subjects to evaluate its effectiveness and generalization further.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Q. and X.X.; methodology, R.Q.; software, R.Q.; validation, R.Q. and X.X.; formal analysis, R.Q.; investigation, H.Y. and K.S.; resources, X.X. and J.Z.; data curation, R.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Q.; writing—review and editing, R.Q. and J.Z.; visualization, R.Q.; supervision, X.X. and J.Z.; project administration, X.X. and J.Z.; funding acquisition, X.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060329) and the Key Research Project of Yunnan Province (202201AT070108).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sha, T.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Kong, W. Semi-supervised regression with adaptive graph learning for EEG-based emotion recognition. MATH BIOSCI ENG. 2023, 20, 11379–11402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Li, B.; Hu, W.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.D. 3DCANN: A Spatio-Temporal Convolution Attention Neural Network for EEG Emotion Recognition. IEEE J BIOMED HEALTH. 2022, 26, 5321–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shuai, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, F. Cooperative Sentiment Agents for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. 2024. Vol. Ithaca: Cornell University Library, arXiv.org.

- Praveen, R.G.; Alam, J. Recursive Joint Cross-Modal Attention for Multimodal Fusion in Dimensional Emotion Recognition. 2024. Vol. Ithaca: Cornell University Library, arXiv.org.

- Huang, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, W.; Wu, M. Multimodal Emotion Recognition Based on Ensemble Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE ACCESS. 2020, 8, 3265–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, X. A Transformer Convolutional Network With the Method of Image Segmentation for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition. IEEE SIGNAL PROC LET. 2024, 31, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Chen, L.; Song, Z.; Lou, X.; Li, D. EEG-based emotion recognition using simple recurrent units network and ensemble learning. BIOMED SIGNAL PROCES. 2020, 58, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fu, G. Emotion recognition by deeply learned multi-channel textual and EEG features. Future Generation Computer Systems. 2021, 119, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khateeb, M.; Anwar, S.M.; Alnowami, M. Multi-Domain Feature Fusion for Emotion Classification Using DEAP Dataset. IEEE ACCESS. 2021, 9, 12134–12142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, Z.; Frounchi, J.; Amiri, M. Wavelet-based emotion recognition system using EEG signal. Neural Computing and Applications. 2017, 28, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, K.; Chen, G. A Channel-Fused Dense Convolutional Network for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition. IEEE T COGN DEV SYST. 2021, 13, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, S.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Coleman, S. Emotion recognition with convolutional neural network and EEG-based EFDMs. NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA. 2020, 146, 107506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zheng, W.; Cui, Z.; Zong, Y.; Li, Y. Spatial-Temporal Recurrent Neural Network for Emotion Recognition. IEEE T CYBERNETICS. 2019, 49, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Han, J.; Min, K. A Multi-Column CNN Model for Emotion Recognition from EEG Signals. SENSORS-BASEL. 2019, 19.

- Chao, H.; Dong, L.; Liu, Y.; Lu, B. Emotion Recognition from Multiband EEG Signals Using CapsNet. SENSORS-BASEL. 2019, 19.

- Algarni, M.; Saeed, F.; Al-Hadhrami, T.; Ghabban, F.; Al-Sarem, M. Deep Learning-Based Approach for Emotion Recognition Using Electroencephalography (EEG) Signals Using Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM). SENSORS-BASEL. 2022, 22.

- Huang, W.; Xue, Y.; Hu, L.; Liuli, H. S-EEGNet: Electroencephalogram Signal Classification Based on a Separable Convolution Neural Network With Bilinear Interpolation. IEEE ACCESS. 2020, 8, 131636–131646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yu, X.; Yin, Y.; Li, T.; Yan, X. Three-dimensional feature maps and convolutional neural network-based emotion recognition. INT J INTELL SYST. 2021, 36, 6312–6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lu, B. Investigating Critical Frequency Bands and Channels for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition with Deep Neural Networks. IEEE transactions on autonomous mental development. 2015, 7, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Liu, A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Chen, X. EEG-based emotion recognition using an end-to-end regional-asymmetric convolutional neural network. KNOWL-BASED SYST. 2020, 205, 106243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Xiong, X.; Zhou, J.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Q. FCAN-XGBoost: A Novel Hybrid Model for EEG Emotion Recognition. SENSORS-BASEL. 2023, 23.

- Chakravarthi, B.; Ng, S.C.; Ezilarasan, M.R.; Leung, M.F. EEG-based emotion recognition using hybrid CNN and LSTM classification. FRONT COMPUT NEUROSC. 2022, 16, 1019776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Pachori, R.B.; Sircar, P. Automated emotion recognition based on higher order statistics and deep learning algorithm. BIOMED SIGNAL PROCES. 2020, 58, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Huang, G.; Dong, Y.; Li, F.; Yang, X.; Liang, Z. PR-PL: A Novel Transfer Learning Framework with Prototypical Representation based Pairwise Learning for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition. 2022. Vol. Ithaca: Cornell University Library, arXiv.org.

- R, P. The Nature of Emotions: Human emotions have deep evolutionary roots, a fact that may explain their complexity and provide tools for clinical practice. AM SCI. 2001, 89, 344–350. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Li, C.; Cheng, J.; Song, R.; Wan, F.; Chen, X. Multi-channel EEG-based emotion recognition via a multi-level features guided capsule network. COMPUT BIOL MED. 2020, 123, 103927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, Y. Multimodal emotion recognition based on manifold learning and convolution neural network. MULTIMED TOOLS APPL. 2022, 81, 33253–33268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimtay, Y.; Ekmekcioglu, E.; Caglar-Ozhan, S. Cross-Subject Multimodal Emotion Recognition Based on Hybrid Fusion. IEEE ACCESS. 2020, 8, 168865–168878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Huang, L.; Sun, Y. EEG emotion recognition based on cross-frequency granger causality feature extraction and fusion in the left and right hemispheres. FRONT NEUROSCI-SWITZ. 2022, 16, 974673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fa Zheng, B.H.S.Z. EEG Emotion Recognition based on Hierarchy Graph Convolution Network. IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine, BIBM. 2021, 2021, 1628–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, A.; Das, S.S.; Teotia, R.; Maheshwari, S.; Sharma, R.; R. CNN and LSTM based ensemble learning for human emotion recognition using EEG recordings. MULTIMED TOOLS APPL. 2023, 82, 4883–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, M.; Dawn, S. Fused CNN-LSTM deep learning emotion recognition model using electroencephalography signals. INT J NEUROSCI. 2023, 133, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du RZhu, S.; Ni, H.; Mao, T.; Li, J.; Wei, R. Valence-arousal classification of emotion evoked by Chinese ancient-style music using 1D-CNN-BiLSTM model on EEG signals for college students. MULTIMED TOOLS APPL. 2023, 82, 15439–15456. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Cheng, C.; Zhao, M.; Deng, H.; Zhang, Y. EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Using Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional LSTM With Attention Mechanism. IEEE J BIOMED HEALTH. 2022, 26, 5406–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Bao, Z.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z. Exploring temporal representations by leveraging attention-based bidirectional LSTM-RNNs for multi-modal emotion recognition. INFORM PROCESS MANAG. 2020, 57, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. An attention-based hybrid deep learning model for EEG emotion recognition. Signal, image and video processing. 2023, 17, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, W.L.; Wang, D.; Shylouskaya, K.; Zhang, Z.; Lim, J.H.; Ang, K.K.; Tan, A.H. EEG-based Emotion Recognition Using Spatial-Temporal Representation via Bi-GRU. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2020, 2020, 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, W.; Li, C.; Song, R.; Cheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Wan, F.; Chen, X. EEG-Based Emotion Recognition via Channel-Wise Attention and Self Attention. IEEE T AFFECT COMPUT. 2023, 14, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. 2018. Vol. Ithaca: Cornell University Library, arXiv.; org.

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tang, C.; Guan, C. MASA-TCN: Multi-Anchor Space-Aware Temporal Convolutional Neural Networks for Continuous and Discrete EEG Emotion Recognition. IEEE J BIOMED HEALTH. 2024, PP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelstra, S.; Muhl, C.; Soleymani, M.; Lee, J.; Yazdani, A.; Ebrahimi, T.; Pun, T.; Nijholt, A.; Patras, I. DEAP: A Database for Emotion Analysis ;Using Physiological Signals. IEEE T AFFECT COMPUT. 2012, 3, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Islam, M.; M. ; Rahman, M.; M.; Mondal, C.; Singha, S.K.; Ahmad, M.; Awal, A.; Islam, M.; S.; Moni, M.A. EEG Channel Correlation Based Model for Emotion Recognition. COMPUT BIOL MED. 2021, 136, 104757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi Ding, N.R.S.Z. TSception: Capturing Temporal Dynamics and Spatial Asymmetry from EEG for Emotion Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing. 2023, 14, 2238–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, F. Deep Sparse Autoencoder and Recursive Neural Network for EEG Emotion Recognition. Entropy (Basel, Switzerland). 2022, 24, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Dai, G.; Lin, G.; Zhang, J.; Kong, W.; Zeng, H. EEG-based emotion recognition using 4D convolutional recurrent neural network. COGN NEURODYNAMICS. 2020, 14, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Tian, Y.; Hou, B.; Dong, J.; Shao, S.; Song, A. A Bi-Stream hybrid model with MLPBlocks and self-attention mechanism for EEG-based emotion recognition. BIOMED SIGNAL PROCES. 2023, 86, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; An, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. EEG emotion recognition based on the attention mechanism and pre-trained convolution capsule network. KNOWL-BASED SYST. 2023, 265, 110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Lai, Y.; Zhao, G.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. An Efficient LSTM Network for Emotion Recognition From Multichannel EEG Signals. IEEE T AFFECT COMPUT. 2022, 13, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xie, H.; Tao, J.; Li, Y.; Pei, G.; Li, T.; Lv, Z. ICaps-ResLSTM: Improved capsule network and residual LSTM for EEG emotion recognition. BIOMED SIGNAL PROCES. 2024, 87, 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bian, N.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, H.; Schuller, B.W. Multi-view domain-adaptive representation learning for EEG-based emotion recognition. INFORM FUSION. 2024, 104, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. IEEE T PATTERN ANAL. 2020, 42, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qilong Wang, B.W.P.Z. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2020, 11531-11539.

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Yin, Z.; Song, Y. Transformers for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition: A Hierarchical Spatial Information Learning Model. IEEE SENS J. 2022, 22, 4359–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topic, A.; Russo, M. Emotion recognition based on EEG feature maps through deep learning network. Engineering science and technology, an international journal. 2021, 24, 1442–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Li, M.; Tian, W.; Hu, D. EEG-based emotion recognition using a temporal-difference minimizing neural network. COGN NEURODYNAMICS. 2024, 18, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, F.; Doss, R. EEG-based emotion recognition via capsule network with channel-wise attention and LSTM models. CCF transactions on pervasive computing and interaction (Online). 2021, 3, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).