1. Introduction

Grade Retention – the repetition of a school year - is a practice regularly in Schools. According to data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), 27% of students in Portugal had repeated a school year at least once during their compulsory education—placing the country above the OECD average in terms of retention rates (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2018, as cited in European Commission, 2020). Santana (2019) suggested that this trend may be attributed to the national perception of retention as beneficial and its entrenched role within the Portuguese school culture.

Understanding grade retention: Academic and psychosocial implications

Retention refers to the practice of requiring students who have not met the academic goals for a given school year (Pipa & Peixoto, 2022) to repeat the same instructional content the following year by staying in the same grade for another year (Klapproth et al., 2016; Martorell & Mariano, 2018; Pereira & Reis, 2014). The primary aim is to strengthen students’ understanding of foundational content before progressing to more advanced ones (Martorell & Mariano, 2018). Since the early 20th century, the academic and developmental consequences of retention have been widely studied, particularly in relation to learning outcomes, behavior, and emotional development (Rebelo, 2009). A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Goos et al.(2021) concluded that the effects of retention are mixed, showing both positive and negative developmental impacts for retained and non-retained students.

There is ongoing debate among researchers regarding the effectiveness of retention as a response to academic underperformance (Borghesan et al., 2022; Martorell & Mariano, 2018; Nunes et al., 2018; Pipa & Peixoto, 2022). Proponents argue that retention may help students overcome learning difficulties (Pereira & Reis, 2014) and achieve expected learning outcomes (Klapproth et al., 2016), as it provides additional time to consolidate foundational knowledge before advancing (Borghesan et al., 2022). Additionally, retention has been associated with higher homogeneity in terms of academic performance in the classroom (Klapproth et al., 2016).

In contrast, researchers have noted the financial costs of supporting an additional year of schooling and the delayed entry of students into the labor market (Borghesan et al., 2022; Pereira & Reis, 2014). Despite these more economical considerations, research has linked retention to adverse psychosocial outcomes for retained students, including reduced self-esteem, impaired peer relationships (Borghesan et al., 2022; Pereira & Reis, 2014), perceived distance from school, a higher likelihood of dropping out of school (Pereira & Reis, 2014), disruptive behavior in classroom (Pagani et al., 2001), and increased risk of stigmatization by peers (Borghesan et al., 2022).

The impact of retention on students' academic performance appears to vary over time. Initially, retained students may exhibit improved academic outcomes (Klapproth et al., 2016; Nunes et al., 2018; Pereira & Reis, 2014). However, these preliminary positive effects are not sustained in the long-term, becoming negligible (Klapproth et al., 2016; Nunes et al., 2018) or even adverse (García-Pérez et al., 2014; Hwang & Cappella, 2018; Pereira & Reis, 2014). Notably, Borghesan et al. (2022) identified some positive long-term effects in math and Portuguese for most of the studied students, although almost one third did experience a learning loss in the long-term. Given that retention is typically a response to prior difficulties in meeting academic goals (Martorell & Mariano, 2018), this practice needs to be overthought in light of these adverse results. It seems essential to evaluate the effects of grade retention not only in terms of academic performance but also in light of broader psychosocial factors such as students’ emotional well-being and self-perception (Nunes et al., 2018). Recent research has increasingly examined these psychosocial dimensions in the context of grade retention.

Notably, Santos et al. (2022) highlighted that retained students reported diminished perceptions of their value as students. Conversely, these students did not indicate lower levels of well-being or school belonging (Santos et al., 2022), which contrasts with findings from previous studies (Pipa & Peixoto, 2022; Van Canegem et al., 2021). In contrast, Hwang and Cappella (2018) and Klapproth et al. (2016) found no significant correlation between psychosocial variables and retention, except a negative association with self-concept levels among seventh-grade students (Klapproth et al., 2016). Pipa and Peixoto (2022) concluded that retained students exhibited reduced task orientation, sense of belonging, and perceived value of school. Moreover, retained students demonstrated less interest in pursuing higher education (Santos et al., 2022) and held lower expectations regarding their academic development (Flores et al., 2013).

The crucial role of student engagement with school for educational outcomes

While academic performance and psychosocial factors are critical in evaluating the impact of grade retention, they do not fully capture how students relate to school on a daily basis. In addition, indicators such as suspension and absenteeism rates offer only a partial view. For example, Martorell and Mariano (2018) found no statistically significant long-term effects of grade retention on these variables, while Gubbels et al. (2019) reported a small increase in absenteeism and a substantial increase in dropout rates associated with previous retention. Although important, such behavioral metrics are insufficient for fully understanding students' connection to school. In light of this, Martorell and Mariano (2018) recommend incorporating socio-emotional dimensions and the quality of students’ relationships with teachers and peers when assessing the consequences of grade retention. Within this broader perspective, student engagement with school emerges as a key indicator —distinct from grades or self-perception.

Although there is no consensus about conceptualization of student engagement with school, growing evidence confirm that it is a multidimensional phenomenon have conceptualized student engagement with school as a multidimensional construct, with some authors testing integrative frameworks of the constructs. For example, Moreira et al. tested the integration of the items and dimensions of two of the most disseminated assessment instruments validity (Inman et al., 2020; Moreira et al., 2009; 2013; 2019; Virtanen et al., 2018) and found that a multifactorial structure for the construct of student engagement registered good validity in several indicators. On the one hand they found support for the integration of individual and contextual dimensions in the same factorial structure; on the other hand, this factorial structure was sensitive to capture the associations between each of the dimensions and both student academic performance and subjective well-being (2020). Individual dimensions include emotional, cognitive, conduct and study behaviors, and the contextual dimensions included teachers, family and peers support for learning, being consistent and integrating the more consensual frameworks (e.g. Reschly & Christenson, 2022). The four individual characteristics of student engagement with school are distinctly characterized refer to different aspects of the students experience towards school. Emotional engagement encompasses affective reactions to school, including a sense of belonging and identification with the institution; cognitive engagement refers to representations and beliefs about school; and study behaviors refers to study strategies and involvement in school work (Fredricks et al., 2004 Moreira et al., 2020; Rechly & Christenson, 2020). The dimensions of family, teachers and peers support for learning refer to students’ perceptions about the support for learning they receive from each of these interpersonal structures (Appleton et al., 2006; Fredricks et al., 2004; Moreira et al., 2020). Student engagement with school emerges then throughout the dynamic interactions between the individual and the contextual characteristics.

Engaged students tend to demonstrate a sense of connection to the educational environment, experience positive emotions in the classroom, and perceive their schoolwork as relevant to achieving future goals. Consequently, they tend to employ adaptive cognitive strategies to facilitate their learning (Moreira & Lee, 2020). Furthermore, student engagement with school is a strong predictor of academic processes and outcomes (e.g., Caldeira et al., 2013; Moreira et al., 2013; 2018; Moreira & Lee, 2020) and serves as a facilitator of academic adaptation (Hirschfield & Gasper, 2011; Silva et al., 2016). Notably, the cognitive dimension of engagement, as opposed to the emotional dimension, seems to significantly influence academic performance (Szabó et al., 2024). However, other researchers have indicated that higher levels of behavioral engagement can predict improved academic grades (Chase et al., 2014) and lower dropout rates (Wang & Fredricks, 2014).

In contrast, low or inconsistent levels of student engagement with school may correlate with disruptive behaviors, low academic performance, and the teacher's perception of diminished behavioral engagement (Archambault & Dupéré, 2016). Additionally, such students often experience conflicting relationships with their teachers (Archambault & Dupéré, 2016). Furthermore, declining levels of behavioral and emotional engagement have been linked to substance use and delinquency in subsequent years (Wang & Fredricks, 2014).

A complex interplay between student engagement and grade retention

Researchers such as Mahatmya et al. (2012) have suggested that retention may negatively impact student engagement with school. This assumption is supported by research conducted in Portugal (Gandra & Cruz, 2020). However, it is crucial to recognize specific limitations inherent in research on student engagement with school, particularly regarding the diverse constructs and dimensions employed across previous studies. For instance, Demanet and Van Houtte (2013) identified increased rates of misconduct among students with a history of retention. However, their study did not account for other dimensions of student engagement, thereby providing an incomplete picture of the broader engagement context. These discrepancies can hinder the comparison of results across different studies and complicate an integrated understanding of the relationship between retention and student engagement with school across its various dimensions.

Additionally, most studies that explore the relationship between grade retention and student engagement with school have captured this interaction at a single point in time, thereby limiting the ability to understand causal relationships. Consequently, there is a pressing need for longitudinal studies that track students over time to better ascertain the effects of retention on both academic and psychosocial development (Santos et al., 2022). This need is particularly pertinent in Portugal, where few studies have been conducted on this topic despite high retention rates compared to other European Union countries (Pipa & Peixoto, 2022).

The main aim of this study is to explore the associations between grade retention and student engagement with school in a population of ninth to eleventh graders, utilizing an integrative conceptual framework that encompasses the various dimensions of school engagement essential for educational outcomes. Thus, the primary research question is: What is the relationship between grade retention and students’ engagement with school?

1.Cross-sectional examination: This part of the study examines the association between grade retention and the multiple dimensions of student engagement with school at a single time point. Based on Mahatmya et al. (2012) and Gandra & Cruz (2021), it is hypothesized that retention is negatively associated with student engagement with school across its various dimensions.

2.Longitudinal examination: In addition, this study investigates the impact of grade retention on student engagement with school over time. Drawing on findings such as those of Santos et al. (2022), it is hypothesized that grade retention will negatively affect engagement longitudinally, accentuating a trend of diminishing engagement with school as students advance academically.

Employing both cross-sectional and longitudinal methodologies provides a robust framework to comprehensively assess the short-term and long-term impacts of retention on students’ engagement with school.

2. Materials and Methods

The first two measurement points of the longitudinal data in this study have been previously detailed in earlier works on student engagement with school (Moreira et al., 2018; Moreira & Lee, 2020). Nevertheless, grade retention has never been linked within this data to student engagement with school so far.

Participants

To explore the aforementioned research question, four measurement points of a longitudinal study were analyzed. Data of the first measurement point was collected at the start of the academic year in 2013 (September-December 2013) in a cohort of students enrolled in their first year of middle school (seventh grade). Prior to data collection approval from the Ethics Committee of Universidade Lusiada Porto, Portugal was obtained. Data were collected in person following authorization from the schools and after obtaining signed informed consent from the students' guardians.

Participants of cross-sectionally examination

The cross-sectionally examination took use of the third measurement point where nearly all students were enrolled in secondary education. The total sample consisted of 727 students from the 9th grade (n = 23), 10th grade (n = 89), and 11th grade (n = 615), with 42.8% male and 57.2% female participants, aged between 14 and 19 years (M = 16.47; SD = 0.59). Regarding maternal education, 56.0% held a degree lower than secondary education (< twelfth grade), 25.2% finished secondary education, and 18.8% held a degree higher than secondary education.

Participants of the longitudinal study

Within the longitudinal data set, the same group of seventh graders was observed at four distinct time points over a period of five years. There was a one-year gap between the first (M0) and the second measurement point (M1), a two-year gap between the second and third measurement point (M1 and M2), and one year between the third and fourth measurement point (M2 and M3). The sample analyzed included only those students who completed the surveys at all four measurement points. In total, 238 students (61.3% female and 38.7% male) aged between 11 and 15 years (M = 13.29; SD = 0.54) at first assessment (M0) and between 16 and 20 years (M = 17.19; SD = 0.49) at the last assessment (M3) were incorporated. During the first data collection, all students were in the seventh grade, and by the final data collection, three were enrolled in the ninth grade, 34 in the eleventh grade, and 201 in the twelfth grade. Regarding maternal education, 56.4% held a degree lower than secondary education (< twelfth grade), 25,5% finished secondary education, and 18.1% held a degree higher than secondary education.

Instruments

To assess student’ engagement with school, the Multifactorial Measure of Student Engagement (MMSE, P. Moreira et al., 2020) was used. This measure assesses seven dimensions of student engagement with school through 27 items, incorporating both individual and contextual dimensions. Student responses were recorded using a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree) (Moreira et al., 2020). This measure demonstrates strong psychometric properties, particularly in terms of structural validity (CFI = .954, RMSEA = .035, SRMR = .037) and internal consistency, both for the overall scale (ω = .93) and for specific dimensions including student conduct (ω = .82), study behaviors (ω = .80), cognitive engagement (ω = .73), emotional engagement (ω = .77), teacher support (ω = .73), family support (ω = .73), and peer support (ω = .78) (Moreira et al., 2020). Furthermore, it also shows indicators of convergent validity between student engagement and academic performance (r = .21, p < .001) as well as emotional well-being (r = .56, p < .001) (Moreira et al., 2020).

Grade Retention was assessed using the academic records of students available at the schools.

Sociodemographic characteristics regarding information on the student (age, gender, school year) and the students’ parents (mother’s education) were assessed during the survey. Mother’s education was scored from “1” = fourth grade educational level to “9” = post doctorate educational level.

Data analysis

Cross-sectional examination.

To investigate the effect of grade retention on components of student engagement with school, a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Amos 26.0 (International Business Machine Corporation, 2019). This multivariate analysis technique enabled the exploration of pathways and measurement models, as well as the examination of external predictors that could explain variability (Marôco, 2010). In this study, gender (0 = male; 1 = female), age, grade level, and maternal education were incorporated into the model as control variables.

Longitudinal examination.

To explore the effect of grade retention on the overall scale of student engagement with school and its seven dimensions, both at the initial time point and over time, a series of latent growth model analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Amos 26.0 software (International Business Machine Corporation, 2019). These models are a specific application of structural equation modeling that allow for the consideration of both intraindividual changes in behavior over time and interindividual differences in these changes (Marôco, 2010). According to Marôco (2010), this statistical technique also facilitates the analysis of external predictors that may explain variability, both in terms of initial values (intercept) and change trajectories (slope). To address missing data, the maximum likelihood method was adopted, as it is considered a suitable approach for latent growth modeling (Marôco, 2010).

The latent growth models were initially conducted using all four observation points. However, due to results that did not yield admissible solutions or minimally acceptable model fit quality, the first measurement point (M0) was excluded from the analyses, leaving only three observation points for longitudinal examination with M1 referred to as the initial time point in all subsequent analyses.

The data analysis was conducted in two phases. To examine variation in both grouped terms (fixed effects) and individual terms (random effects) for the overall scale of student engagement with school and its seven dimensions across the three observation points, three unconditional latent growth models were initially used. For model identification, it was assumed that the slope was zero at the initial time point (M1) and that there was a linear growth tendency thereafter. The path weights between the slope and the manifest variables were set at 0, 0.66, and 1, respectively. The latent intercept variable was included in the models to examine the average value of the dependent variables at the three observation points, with all paths from the intercept to the dependent variables fixed at a weight of 1. The mean of the intercept and slope enabled the determination of the average starting values of the dependent variables and their average rate of change over time. The variances of the intercept and slope were used to assess individual differences in both baseline values and the rate of change in student engagement with school and its seven dimensions. In the second phase, conditioned models were estimated, in which retention variables at M2 and M3, as well as control variables (gender, age, school year, and mother’s education) assessed at all three measurement points, were included as predictors for the intercept and slope. Effects from independent variables at later observation points were not regressed onto earlier ones, as they could not have exerted any influence.

To address missing data, the maximum likelihood method was employed, deemed suitable for latent growth modeling (Marôco, 2010). To assess the fit quality of the model, the Chi-square test (Chi²/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were utilized (Marôco, 2010). Thresholds for good model fit were established as Chi2/df < 5, TLI and CFI > 0.90, and RMSEA < 0.08 (Arbuckle, 2008).

3. Results

Cross-Sectional Results

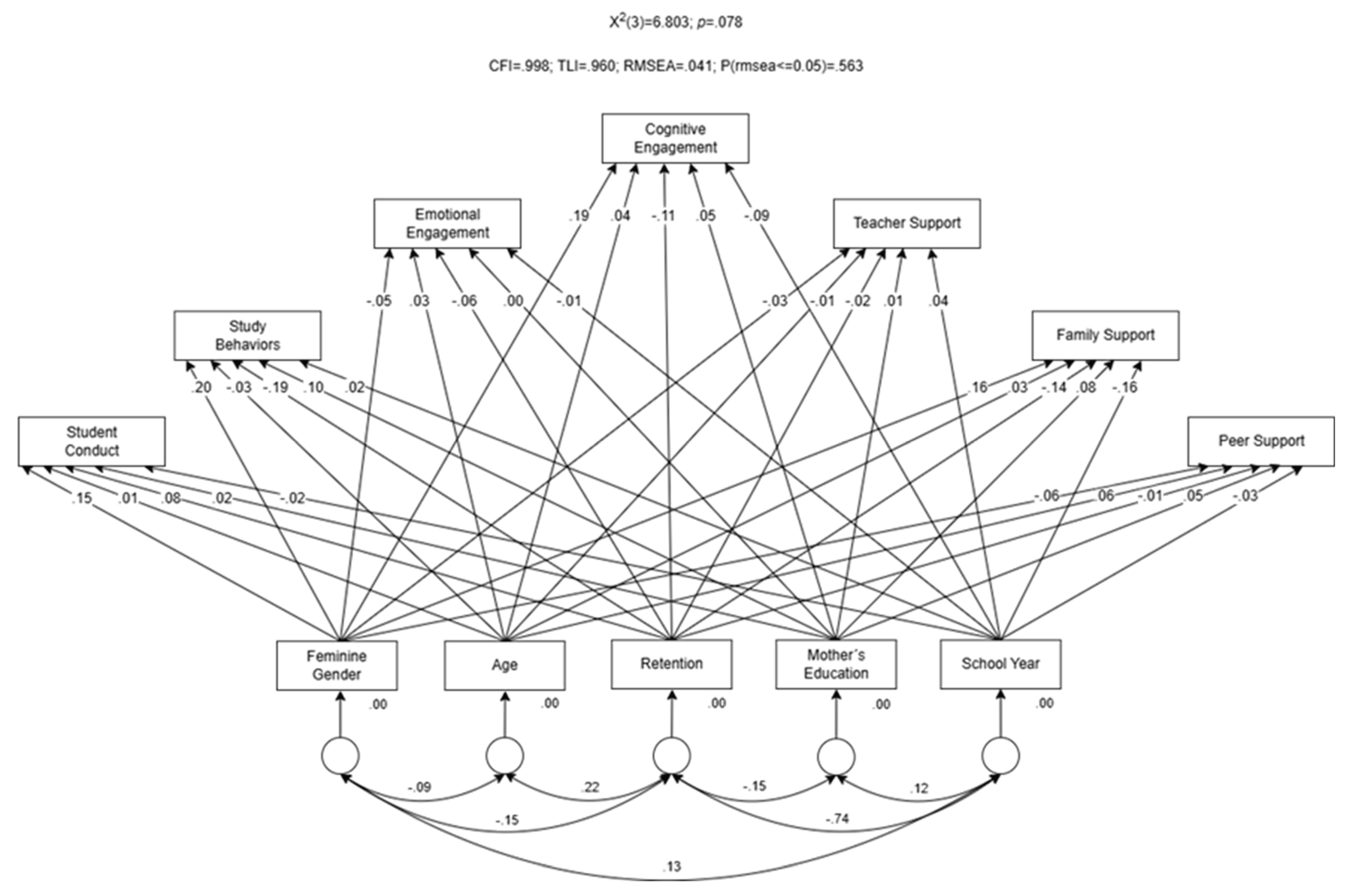

Figure 1 illustrates the analyzed model. Based on modification indices (MI) > 4 (p < .001), nonsignificant correlations between the error terms of dependent variables were removed, and some measurement errors in the dependent variables were correlated to enhance the model's fit to the data, as recommended by Marôco (2010).

Table 1 summarizes the standardized coefficients and corresponding p-values for the model testing the effect of retention on the seven dimensions of student engagement with school, while controlling for sociodemographic variables (gender, age, school year, and mother’s education). The results indicated that retention is negatively correlated with study behaviors (r = -.188; p < .001) and family support (r = -.139; p = .015). Regarding the control variables, it was found that female students tended to report a more positive perception of student conduct (r = .155; p < .001) and study behaviors (r = .197; p < .001), as well as higher levels of cognitive engagement (r = .189; p < .001) and family support (r = .164; p < .001), compared to male students.

Longitudinal Results

Results of descriptive analysis for student engagement variables across the three measurement points used for analysis are summarized in

Supplementary Table 1. Preliminary analyses indicated that the study variables exhibited absolute values of skewness and kurtosis below 3 and 10, respectively, which supports the assumption of multivariate normality (Kline, 2005). Based on modification indices (MI) > 4 (p < .001), some measurement errors in the dependent variables were correlated to achieve a better fit of the model to the data, following the recommendations of Marôco (2010).

Results of unconditional latent growth models

The unconditional latent growth models presented in

Supplementary Figures 1–8 demonstrated good model fit, with the exception of the models for student conduct and emotional engagement.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the unconditional models for the overall scale of student engagement with school and its seven dimensions, presenting the unstandardized estimates (and corresponding standard errors) for both the mean (fixed effect) and variance (random effect) of the intercept and slope.

As noted, the intercept mean reflects the initial average levels of the dependent variables, while its variance indicates whether individual differences exist in both the initial values and the rate of change in student engagement with school across its seven dimensions.

The results show that both the mean and the variance of the intercept were statistically significant. This suggests that there was interindividual heterogeneity in students’ initial levels of the dependent variables.

The mean and variance of the slope provided insight into the average rate of change of the dependent variables over time (fixed effects), as well as the existence of individual differences in these change trajectories (random effects). The results showed negative significant mean slopes for the overall scale of student engagement with school and the dimensions of cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, student conduct, and peer support, suggesting a slight decline in their average values throughout the study period. In contrast, the mean slopes for study behaviors, teacher support, and family support were not statistically significant, indicating no significant changes in these components over time.

With regard to the random effects, the variance of the slopes for the two dimensions student conduct and teacher support, was not statistically significant, indicating that participants did not differ in their individual change trajectories. For the remaining dependent variables, however, slope variances were statistically significant, revealing interindividual variability. Given this scenario, it was deemed relevant to include additional predictor variables in the models, specifically the predictor variable retention, along with control variables (age, gender, mother's education level, and school grade level), to help explain the observed heterogeneity in participants' baseline values and change patterns over time.

With the exception of student conduct and teacher support, all other dependent variables showed statistically significant and negative correlations between intercept and slope. This indicates that students with higher initial levels of student engagement with school (as a composite variable), or in the dimensions of cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, study behaviors, family support, and peer support, tended to exhibit steeper declines over time. Conversely, students with lower initial levels tended to show slower declines or less pronounced negative slopes over time.

Conditional Latent Growth Models

Following the estimation of the unconditional latent growth models, control variables (female gender, age, school year, and mother’s education) and the predictor variable (retention) at all three measurement points were introduced as predictors of the initial levels (intercepts) and growth trajectories (slopes) of the dependent variables.

When running the models with all control and predictor variables observed across the three measurement points, the results revealed a high correlation between variables at different moments—for example, between retention at M2 and M3. This constrained the analyses and leads to decision to only include one measurement point per variable. All results are illustrated in

Supplementary Figures 9–16. One severe outlier was removed, reducing the final sample to 238 participants. The proposed models demonstrated good fit, with the exception of those for student conduct, teacher support, and family support.

As shown in

Table 3, retention emerged as the only significant predictor of the slope of the overall scale of student engagement with school, indicating that retained students exhibited a statistically significant decrease in engagement over time compared to their non-retained peers. When examining the specific dimensions of student engagement with school, retention was the strongest predictor of change in study behaviors over time, with retained students showing a significant decline in this dimension of student engagement with school compared to non-retained students.

Gender was a significant predictor of the initial levels of student conduct—female students began with significantly higher levels than male students.

Regarding study behaviors, the control variables gender, age, and school year predicted the slope of this dimension: female students consistently demonstrated higher levels of study behavior over time than male students. Additionally, students with higher age and grade level at M2 exhibited significantly steeper declines in study behavior over time than younger students or those in lower grades.

Regarding cognitive engagement, gender was a significant predictor, with female students reporting higher levels of cognitive engagement over time compared to male students.

School year (observed at M2) predicted the slope of peer support: as students progressed to higher grades, their perception of support from peers increased. However, gender was also a significant predictor, with female students reporting lower levels of perceived peer support over time compared to their male peers.

For the dimensions of emotional engagement and teacher support, none of the independent variables included were statistically significant predictors of either the intercepts or slopes.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between grade retention and students’ engagement with school. To achieve this aim, two examinations of a longitudinal data set had been done: 1. A cross-sectional and 2. A longitudinal one. First, the cross-sectional study was used to examine the association between retention and students’ engagement with school in a huge sample of secondary students in Portugal. Subsequently, the longitudinal data set was used to analyze the effect of retention on the overall scale of student engagement with school and their seven dimensions over time. Gender, age, mother's educational level, and school year were included in the model as control variables.

The hypotheses initially proposed in this study, supported by previous research, appear to have been confirmed by the results. Notably, Gandra and Cruz (2021) identified grade retention as a direct contributor to decreased school engagement in Portugal. Similarly, Pagani et al. (2001) found in a longitudinal sample of 1,830 elementary school students in a Canadian province negative effects of retention on academic performance and behavior, both in the medium and long term. Retention was perceived as a marker of failure, frustration, humiliation, shame, and other negative emotions (Pagani et al., 2001). The results of the current study add valuable insights about the negative effect of retention on students’ engagement with school.

The role of grade retention for students’ engagement with school

Students who had repeated a grade reported lower levels of study behaviors and family support. Literature suggests that family support has a significant effect on school engagement. Specifically, Santana (2019) noted that students encouraged by their parents to make choices about school relationships were more engaged than those who did not receive such parental encouragement. Similarly, Lahaye et al. (2001, as cited in Santana, 2019) pointed out that how young people perceived parental involvement in their school life influenced their views on both school and family relationships.

The results of the longitudinal examination were consistent with previous research, indicating that retained students experienced a statistically significant decline in student engagement with school over time compared to non-retained students. Specifically, Gandra and Cruz (2021) conducted a study examining student engagement with school and retention in Portugal, concluding that retention in primary and middle school is associated with lower engagement. Similarly, Mahatmya et al. (2012) explored the relationship between retention and engagement, finding a negative correlation between these variables.

Retention emerged as a key predictor of changes in study behaviors over time. Retained students exhibited a significant decrease in this dimension of student engagement with school compared to non-retained peers. This finding aligns with those of Santos et al. (2022), who reported lower values in the behavioral engagement dimension among retained students. Furthermore, Wang and Fredricks (2014) found that students with higher academic success, as measured by grades, demonstrated elevated levels of behavioral engagement.

Given the results of previous studies which show that retention is associated with a small increase in absenteeism and a substantial increase in school dropout rates (Gubbels et al., 2019), the decreased engagement with school of retained students might be one plausible explanation which needs further investigation.

When analyzing control variables, female students tended to report more positive perceptions of their student conduct and study behaviors, as well as higher levels of cognitive engagement and family support, compared to male students. Additionally, gender emerged as a significant predictor in cognitive engagement, with female students reporting higher levels of cognitive engagement over time compared to male students. It is important to note that previous studies with Portuguese samples (Nunes et al., 2018; Pereira & Reis, 2014) showed higher retention rates among boys, highlighting the importance of examining the relationship between retention and other variables under control of students’ gender. Furthermore, gender showed statistical significance as a predictor of the slope of peer support, with female students reporting lower levels over time compared to male students.

Implications

Studies examining the intersection of inclusion with retention and student engagement with school are almost nonexistent. In particular students' opinions and experiences with retention are scarce, with most of the available perspectives in the literature coming from teachers or individuals associated with them. The current study gives an important insight into retention and students’ engagement with school. However, the Portuguese legislative framework concerning school inclusion (Decree-Law No. 54/2018 of July 6) is still new and still developing. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies, particularly in Portugal, continue to explore the effects of inclusive practices that promote academic success, as suggested by authors like Nunes et al. (2018).

The main aim of repeating a grade is to strengthen the understanding of academic content for those students failing in reaching the academic goals (Martorell & Mariano, 2018). Consistent with other researchers studying the effects of retention among Portuguese students (Borghesan et al., 2022; Nunes et al., 2018; Pereira & Reis, 2014), this study emphasizes the importance of modifying the application of retention practices in cases of academic failure. Nunes et al. (2018) and Borghesan et al. (2022), for instance, recommended adjusting the criteria for applying retention to target students with the lowest grades, thereby reducing the overall number of students retained. But reducing the overall number of students repeating a grade won’t help retained students overcome the psychosocial problems associated with retention shown in the literature (e.g., Borghesan et al., 2022; Goos et al., 2021). Pereira and Reis (2014) argued for the necessity of complementing the practice of retention with additional strategies and educational interventions to enhance student performance, especially for those retained in the early years of education. The results of this study suggest that these strategies might not only concern academic performance but different dimensions of student engagement with school. This could help reduce absenteeism and dropout rates in the long-term.

5. Conclusions

Challenges for Inclusive Education and for Person-Centered Schools

This study reveals that retained students showed significantly lower levels of student engagement with school compared to their non-retained peers. By showing the negative effects of retention on student engagement, our research underscores the critical need for reevaluating retention practices at Portuguese schools. This leads to the claim of shaping educational policies and designing interventions that actively promote student engagement with school and reduce the reliance on retention as a remedial strategy. Furthermore, our findings highlight the potential long-term consequences of retention, emphasizing the importance of proactive measures to prevent the need for retention and avoid school drop-out or placement in Special Education. Such insights contribute to the ongoing dialogue about effective strategies for fostering inclusive and supportive school environments that cater to the diverse needs of all students (Decree-Law No. 54/2018 of July 6).

Recent evidence coming from systematic review studies confirm that student engagement with school is one of the strongest predictors of student academic performance (Kampylis et al., 2024). Considering the research that we have being conducting on student engagement with school (and its role in student academic processes and outcomes e adolescents’ positive development), the results of the present study have implication for educational and societal in several ways.

First, student engagement with school is a process (Moreira, Moreira et al., 2018; Moreira, Faria et al., 2019) thar emerges from the interaction between individual dimensions and contextual influences. Individual dimensions relevant for the process of development of student engagement with school include emotions (Faria et al., 2023; Moreira, Cunha & Inman, 2019), satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Cruz et al., 2024; Inman et al., 2023), personality (Moreira, Cunha, Inman & Oliveira, 2019; Moreira, Pedras & Pombo, 2020; Moreira et al., 2021; 2023a; 2023b), approaches to learning (Moreira, Inamn, Rosa at al., 2020), identity (Moreira, Inman, Cunha & Cardoso, 2019), behavioral and emotional regulation (Moreira, Inman & Cloninger, 2021) and well-being (Moreira et al., 2023c; Moreira, Pedras, Silva et al., 2021).

Second, student engagement is also a result, as it emerges from the interaction from the individual characteristics and the contexts, including families (Robrigues et al., 2025) schools. By another works, the level of engagement with school of a student in a specific time at a specific school is also an indicator of the quality of the cumulative experiences of that student with school (Moreira, Cunha & Inman, 2020; Moreira Cunha, Inman & Oliveira, 2019; Moreira & Lee, 2020). In fact, the quality of such experiences is dependent on the interactions between the individual and contextual dimensions involved in students’ experiences with school (Moreira, Cunha & Inman, 2020; Moreira Cunha, Inman & Oliveira, 2019; Moreira & Lee, 2020). Engagement as an outcome reflects how well, or poorly, schools succeed in offering their students the necessary conditions for having school experiences that meet psychological needs and keep all their students involved with school (Moreira, Cunha & Inman, 2020; Moreira Cunha, Inman & Oliveira, 2019; Moreira & Lee, 2020). There is a growing body of evidence that school characteristics have significant effects on student’s functioning, including on engagement with school (Dias et al., 2015; Moreira, Cunha, Inman & Oliveira, 2019; Moreira, Dias, Matias et al., 2018; Moreira & Garcia, 2019; Moreira & Lee, 2020; Moreira, Oliveira, Dias et al., 2014).

Third, student engagement with school is especially relevant for students especially placed at risk, including students from ethnic minorities such as it is the case of gypsy [Roma] students (Moreira, Bilimória & Lopes, 2021; 2022) and students with special educational needs (Moreira, Bilimória, Alves et al., 2015; Moreira, Bilimória, Pedrosa, et al., 2015).

In sum, schools need to assume their responsibility in promoting positive academic trajectories for all their students, including shifting from a materialistic oriented paradigm to a person-centered school’s paradigm. Person-centered schools are contexts where all the dimensions of holistic functioning are considered and systematic promotion of the dimensions identified by robust evidence as crucial for student’s holistic positive development, such as social-emotional competences (Costa et al., 2025; Moreira et al., 2010; 2014) and positive personality development such as character strengths (Moreira, Inman & Cloninger).

This urgent need is well described in the following:

“Technological and material resources are available for humans at an unprecedented level, and yet a significant percentage of the population report some degree of subjective suffering, functioning impairment, or medical ill-being associated with patterns of maladaptive psychosocial functioning/lifestyles.

This suggests that there is a vital need for new approaches to promoting human development. School is one of the most powerful contexts for implementing such approaches. However, a new paradigm in education is required to help schools be more efficient at preparing their students to deal adaptively with the challenges facing humanity. Schools need to be able to promote the processes underlying human holistic development, rather than emphasizing the development of mainly logical-propositional dimensions, as is the case of materialistic-oriented conventional schools (…)

School is an ideal context for implementing a holistic approach to the promotion of human functioning. However, the effectiveness of any means aiming to promote positive adaptation in (person-centered) schools depends on intentionality, coordination, systematization, continuity, evaluation, and monitoring. We need to develop and test coherent frameworks that describe the common factors, and dynamics amongst them, involved in changing conventional schools to person- centered schools. This process is in its embryonic phase and is one of the current main challenges for research and practices of behavioral sciences. If done effectively, it will have substantial implications, not only for individuals’ well-being, but also for societal organization and development (Moreira & Garcia, 2019, pags. 183-184).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Descriptive Statistics of Variables Across the three Measurement Points of the Longitudinal Data.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Conceptualization, A.S. and P.A.S.M.; methodology, A.S. and P.A.S.M.; software, M.R., P.A.S.M; validation, A.S. and P.A.S.M; formal analysis, A.S., M.R. and P.A.S.M; investigation, A.S. and P.A.S.M.; resources, P.A.S.M.; data curation, A.S. and P.A.S.M.; writing—original draft preparation A. S., M. J.R., N.P, P.A.S.M; writing—review and editing, A. S., M.J.R., N.P, A.C.R., P.A.S.M; A.S., M. R., M.J.R. N.P. and P.A.S.M.; supervision, A.C.R. and P.A.S.M.; project administration, P.A.S.M.; funding acquisition, P.A.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) [grant numbers PTDC/CPE-CED/122257/2010 and PTDC/MHC-CED/2224/2014].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Lusíada Porto, Portugal.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables Across the three Measurement Points of the Longitudinal Data.

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables Across the three Measurement Points of the Longitudinal Data.

| Variable |

Range |

M |

SD |

Skew |

Kurt |

| M1 Student Engagement with school |

1-5 |

3.34 |

0.50 |

0.09 |

0.51 |

| M2 Student Engagement with school |

1-5 |

3.23 |

0.55 |

-0.17 |

0.04 |

| M3 Student Engagement with school |

1-5 |

3.32 |

0.55 |

-0.23 |

0.09 |

| M1 Student Conduct |

1-4 |

3.37 |

0.41 |

-0.37 |

2.20 |

| M2 Student Conduct |

1-4 |

3.19 |

0.49 |

-0.35 |

0.39 |

| M3 Student Conduct |

1-4 |

3.25 |

0.48 |

-0.50 |

0.96 |

| M1 Study Behaviors |

1-5 |

3.32 |

0.77 |

-0.01 |

0.04 |

| M2 Study Behaviors |

1-5 |

3.27 |

0.78 |

-0.23 |

0.00 |

| M3 Study Behaviors |

1-5 |

3.38 |

0.78 |

-0.32 |

0.19 |

| M1 Emotional Engagement |

1-4 |

3.27 |

0.40 |

-0.56 |

3.87 |

| M2 Emotional Engagement |

1-4 |

3.03 |

0.47 |

-0.04 |

0.55 |

| M3 Emotional Engagement |

1-4 |

3.01 |

0.45 |

-0.18 |

1.62 |

| M1 Cognitive Engagement |

1-4 |

3.18 |

0.43 |

-0.24 |

0.20 |

| M2 Cognitive Engagement |

1-4 |

3.12 |

0.47 |

-0.56 |

0.69 |

| M3 Cognitive Engagement |

1-4 |

3.10 |

0.43 |

-0.30 |

-0.04 |

| M1 Teacher Support |

1-4 |

2.95 |

0.50 |

-0.12 |

0.77 |

| M2 Teacher Support |

1-4 |

3.03 |

0.52 |

-0.48 |

1.27 |

| M3 Teacher Support |

1-4 |

3.06 |

0.48 |

-0.34 |

1.50 |

| M1 Family Support |

1-4 |

3.39 |

0.51 |

-0.63 |

0.50 |

| M2 Family Support |

1-4 |

3.60 |

0.47 |

-1.07 |

0.80 |

| M3 Family Support |

1-4 |

3.57 |

0.49 |

-0.99 |

0.84 |

| M1 Peer Support |

1-4 |

3.16 |

0.46 |

-0.48 |

1.55 |

| M2 Peer Support |

1-4 |

3.11 |

0.49 |

-0.32 |

0.95 |

| M3 Peer Support |

1-4 |

3.09 |

0.46 |

-0.23 |

0.70 |

References

- Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the Student Engagement Instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 427–445. [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2008). AMOS 17.0 User’s Guide. SPSS.

- Archambault, I., & Dupéré, V. (2016). Joint trajectories of behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in elementary school. The Journal of Educational Research, 110(2), 188–198.

- Borghesan, E., Reis, H., & Todd, P. E. (2022). Learning Through Repetition? A Dynamic Evaluation of Grade Retention in Portugal (22–030; PIER Working Paper, pp. 1–80). Penn Institute for Economic Research, University of Pennsylvania. https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/system/files/working-papers/22-030%20PIER%20Paper%20Submission.pdf.

- Caldeira, S. N., Fernandes, H. R., & Tiago, M. T. B. (2013). O envolvimento do aluno na escola e sua relação com a retenção e transição académica: Um estudo em escolas de S. Miguel. Atas do XII Congresso Internacional Galego-Português de Psicopedagogia, 7027–7049. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.3/3944.

- Chase, P. A., Hilliard, L. J., Geldhof, G. J., Warren, D. J. A., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Academic achievement in the high school years: The changing role of school engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 884–896. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. J., Inman, R. A. & Moreira, P. A. S. (2025). Social–emotional expertise and subjective wellbeing in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 113236. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S., Sousa, M., Peixoto, M., Meireles, A., Marques, S., Faria, S. & Moreira, P.A.S. (2024). The Interplay Between Emotional Well-being, Self-compassion, and Basic Psychological Needs in Adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2318340. [CrossRef]

- Demanet, J., & Van Houtte, M. (2013). Grade retention and its association with school misconduct in adolescence: A multilevel approach. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 24(4), 417–434. [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Oliveira, J.T., Moreira, P.A.S., & Rocha, L. (2015). Percepção dos alunos acerca das estratégias de promoção do sucesso educativo e envolvimento dos alunos com a escola [Relation between school success promotion strategies and students’ engagement with school]. Estudos de Psicologia, 32(2), 187-199.

- European Commission. (2020). Equity in school education in Europe. Structures, policies and student performance. Eurydice report. Publications Office of the European Union. [CrossRef]

- Faria, S., Pedras, S., Lopes, J., Inman, R.A., & Moreira, P.A.S. (2023). Subjective well-being and school engagement before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic: What good are positive emotions? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 33, 973–985. [CrossRef]

- Flores, I., Mendes, R., & Velosa, P. (2013). O que se passa que os alunos não passam? In Conselho Nacional de Educação (Ed.), Estado da Educação (pp. 374–391). Conselho Nacional de Educação. https://www.cnedu.pt/content/edicoes/estado_da_educacao/Estado-da-Educacao-2013-online-v4.pdf.

- Gandra, D., & Cruz, J. (2021). Engagement with school and retention. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 9(3), 225–235. [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, J., Hidalgo-Hidalgo, M., & Robles-Zurita, J. (2014). Does grade retention affect students’ achievement? Some evidence from Spain. Applied Economics, 46. [CrossRef]

- Goos, M., Pipa, J., & Peixoto, F. (2021). Effectiveness of grade retention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 34, 100401. [CrossRef]

- Gubbels, J., van der Put, C. E., & Assink, M. (2019). Risk Factors for School Absenteeism and Dropout: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1637–1667. [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, P. J., & Gasper, J. (2011). The relationship between school engagement and delinquency in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(1), 3–22. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. H. J., & Cappella, E. (2018). Rethinking Early Elementary Grade Retention: Examining Long-Term Academic and Psychosocial Outcomes. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 11(4), 559–587. [CrossRef]

- Inman, R.A., Costa, P., & Moreira, P.A.S. (2023). Psychometric Properties of the Portuguese Adolescent Students’ Basic Psychological Needs at School Scale (ASBPNSS) and evidence of differential associations with indicators of subjective wellbeing. Journal of PsychoEducational Assessment, 41(1), 100–119. [CrossRef]

- Inman, R. A., Moreira, P. A., Cunha, D., & Castro, J. (2020). Assessing the Dimensionality of Student School Engagement Survey: Support for a multidimensional bifactor model / Evaluación de la dimensionalidad del Student School Engagement Survey: apoyo para un modelo multidimensional bifactor. Revista de Psicodidactica, 25(2), 109-118, E66. [CrossRef]

- International Business Machine Corporation. (2019). SPSS AMOS (Versão 26.0) [Software de Computador]. International Business Machine Corporation. https://www.ibm.com/products/structural-equation-modeling-sem.

- Kampylis, P., Fragkiadaki Theodoroulea, M., Kandila, M., Cholezas, I., Mobilio, V., Sampson, D., Lievore, I., Mauro, V., Gunzelmann, S., Lanoë, M., Maurya, P., Moulin, L., Ortiz, L., Passaretta, G., & Moreira, P. (2024). Tracing educational inequalities in primary and secondary schools – Insights from a systematic review of longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional studies. LINEup Project – Deliverable 2.1. European Research Agency, European Comission.

- Klapproth, F., Schaltz, P., Brunner, M., Keller, U., Fischbach, A., Ugen, S., & Martin, R. (2016). Short-term and medium-term effects of grade retention in secondary school on academic achievement and psychosocial outcome variables. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 182–194. [CrossRef]

- Mahatmya, D., Lohman, B., Matjasko, J., & Farb, A. (2012). Engagement Across Developmental Periods. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (1st ed., pp. 45–63). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. (2010). Análise de equações estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, Software & Aplicações. ReportNumber. https://www.wook.pt/livro/analise-de-equacoes-estruturais-joao-maroco/24699200.

- Martorell, P., & Mariano, L. T. (2018). The Causal Effects of Grade Retention on Behavioral Outcomes. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 11(2), 192–216. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P. A. S., & Dias, M. A. (2019). Tests of factorial structure and measurement invariance for the Student Engagement Instrument: Evidence from middle and high school students. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 7(3), 174–186. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P. A. S., Cunha, D., & Inman, R. A. (2020). An Integration of Multiple Student Engagement Dimensions into a Single Measure and Validity-Based Studies. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 38(5), 564–580. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P. A. S., Dias, A., Matias, C., Castro, J., Gaspar, T., & Oliveira, J. (2018). School effects on students’ engagement with school: Academic performance moderates the effect of school support for learning on students’ engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 67–77. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P., Dias, P., Vaz, F. M., & Vaz, J. M. (2013). Predictors of academic performance and school engagement—Integrating persistence, motivation and study skills perspectives using person-centered and variable-centered approaches. Learning and Individual Differences, 24, 117–125. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S & Garcia, D. (2019). Person-centered schools. In D. Garcia, T. Archer & R.M. Kostrzewa (Eds.), Personality and Brain Disorders: Associations and Interventions (pp. 183-228). Contemporary Clinical Neuroscience Series Title. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S, Crusellas, L.; Sá, I.; Gomes, P. & Matias, C. (2010). Evaluation of a manual-based programme for the promotion of social and emotional skills in elementary school children: Results from a 4-year study in Portugal. Health Promotion International, 25(3), 309-317. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S. & Dias, M.A. (2019). Tests of factorial structure and measurement invariance for the Student Engagement Instrument: Evidence from middle and high school students. International Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 7(3), 174-186. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2017.1414004.

- Moreira, P.A.S. & Lee, V.E. (2020). School social organization influences adolescents' cognitive engagement with school: The role of school support for learning and of autonomy support. Learning and Individual Differences, 80, 101885. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Bilimória, H. & Lopes, S. (2021). Subjective wellbeing in gypsy [Roma] adolescents. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 21(1), 35-46.

- Moreira, P.A.S., Bilimória, H., & Lopes, S. (2022). Engagement with school in Gypsy students attending school in Portugal. Intercultural Education, 33(2), 173-192. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Bilimória, H.; Alvez, P.; Santos, M.A.; Macedo, A.C.; Maia, A.; Figueiredo, F.; & Miranda, M.J. (2015). Subjective wellbeing in students with Special Educational Needs (SEN). Cognition, Brain, Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 19(1), 75-97.

- Moreira, P.A.S., Bilimória, H.; Pedrosa, C.; Pires, M.F.; Cepa, M.J.; Mestre, M.D.; Ferreira, M.; & Serra, N. (2015). Engagement with school in students with Special Educational Needs. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy, 15(3), 361-375. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/560/56041784004.pdf.

- Moreira, P.A.S., Cunha, D. & Inman, R. (2019). Achievement Emotions Questionnaire-Mathematics (AEQ-M) in Adolescents: Factorial structure, measurement invariance and convergent validity with personality. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16(6), 750-762. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Cunha, D. & Inman, R.A. (2020). An integration of multiple student engagement dimensions into a single measure and validity-based studies. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 38(5) 564–580. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Cunha, D., Inman, R., & Oliveira, J. (2019). Integrating healthy personality development and educational practices: The case of student engagement with school. In D. Garcia, T. Archer & R.M. Kostrzewa (Eds.), Personality and Brain Disorders: Associations and Interventions (pp. 227-250). Contemporary Clinical Neuroscience Series Title. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Dias, A.; Matias, C., Castro, J., Gaspar, T., & Oliveira, J. (2018). School effects on students’ engagement with school: academic performance moderates the effect of school support for learning on students’ engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 67-77. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Faria, V., Cunha, D., Inman, R. & Rocha, M. (2020). Applying the transtheoretical model to adolescent academic performance using a person-centered approach: a latent cluster analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 78, 101818. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Inman, R., Cunha, D. & Cardoso, N. (2019). Functions of identity in the context of being a student: Development and validation of the Functions of Student Identity Scale. Identity- An International Journal of Theory and Research, 19(1) 29–43. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P. A.S., Inman, R. A., & Cloninger, C. R. (2023a). O Inventário de Temperamento e Carater Revisto (TCI-R): Normas para a população Portuguesa [The Revised Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-R): Normative data for the Portuguese population]. Psychologica, 66, e066001. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Inman, R.A & Cloninger, C.R. (2022). Virtues in action are related to the integration of both temperament and character: Comparing the VIA Classification of Virtues and Cloninger’s Biopsychosocial Model of Personality. Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(6), 858-875. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Inman, R.A. & Cloninger, C.R. (2023b). Three joint temperament-character configurations account for learning, personality and well-being: Normative demographic findings in a representative national population. Frontiers in Psychology, 14: 1193441. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Inman, R.A., & Cloninger, C.R. (2023c). Disentangling the personality pathways to well-being. Scientific Reports, 13, 3353. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Inman, R.A., Cloninger, K. & Cloninger, C.R. (2021). Personality and student engagement with school: a biopsychosocial and person-centered approach. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 691-713. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Inman. R.A., Cloninger, C.R. (2021). Personality networks and emotional and behavioral problems: Integrating temperament and character using Latent Profile and Latent Class Analyses. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52, 856-868. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Jacinto, S.; Pinheiro, P.; Patrício, A.; Crusellas, L.; Oliveira, J.T.; & Dias, A. (2014). Long-term impact of social and emotional skills promotion. Psychology/Reflexão e Crítica, 27(4), 634-641. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Machado Vaz, F.; Dias, P., & Petracchi, P. (2009). Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the School Engagement Instrument. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 24(4), 303-317. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Moreira, F.; Cunha, D., & Inman, R. (2018). The Academic Performance Stages of Change Inventory (APSCI): An application of the Transtheoretical Model to academic performance. International Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 8 (3), 199-212. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Oliveira, J.T.; Dias, P.; Vaz, F.M.; & Torres-Oliveira, I. (2014). The Students’ Perceptions of School Success Promoting Strategies Inventory (SPSI): Development and validity evidence-based studies. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17, E61. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S., Pedras, S. & Pombo, P. (2020). Students` personality contributes more to academic performance than well-being and learning approach – implications for sustainable development and education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10 (4), 1132-1149. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S.; Pedras, S., Silva, M., Moreira, M. & Oliveira, J. (2021). Personality, attachment, and wellbeing in adolescents: Effects of personality and attachment. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(4), 1855-1888. [CrossRef]

- Moreira. P.A.S., Inman, R.A., Rosa, I., Cloninger, K. Duarte, A. & Cloninger, C.R. (2020). The psychobiological model of personality and its association with student approaches to learning: Integrating temperament and character. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(4), 693-709. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L. C., Reis, A. B., & Seabra, C. (2018). Is retention beneficial to low-achieving students? Evidence from Portugal. Applied Economics, 50(40), 4306–4317.

- Pagani, L., Tremblay, R. E., Vitaro, F., Boulerice, B., & McDuff, P. (2001). Effects of grade retention on academic performance and behavioral development. Development and Psychopathology, 13(2), 297–315. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. C., & Reis, H. (2014). Grade retention during basic education in Portugal: Determinants and impact on student achievement. Economic Bulletin and Financial Stability Report Articles and Banco de Portugal Economic Studies, 1(1), 61–83.

- Pipa, J., & Peixoto, F. (2022). One Step Back or One Step Forward? Effects of Grade Retention and School Retention Composition on Portuguese Students’ Psychosocial Outcomes Using PISA 2018 Data. Sustainability, 14(24), Artigo 16573. [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, J. (2009). Efeitos da retenção escolar, segundo os estudos científicos, e orientações para uma intervenção eficaz: Uma revisão. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, 43(1), 27–52. [CrossRef]

- Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (Eds.). (2022). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer Nature.

- Robrigues, B., Costa, D., Rodrigues, M., Inman, R., Cid, X., Moreira, P. A. S. (2025). Mother’s Education and Student Engagement with School. Submitted, Under Review.

- Santana, M. R. R. (2019). Práticas e Representações acerca da Retenção Escolar (Repositório Universidade Nova) [Tese de Doutoramento, Universidade Nova de Lisboa]. Repositório Universidade Nova. https://run.unl.pt/handle/10362/89715.

- Santos, N., Monteiro, V., & Carvalho, C. (2022). Impact of grade retention and school engagement on student intentions to enrol in higher education in Portugal. European Journal of Education, 58(1), 130–150. [CrossRef]

- Silva, S. L. R., Ferreira, J. A. G., & Ferreira, A. G. (2016). Construção e estudo Exploratório do questionário do envolvimento em contexto de ensino superior. In Envolvimento dos Alunos na Escola: Perspetivas da Psicologia e Educação—Motivação para o Desempenho Académico (pp. 62–76). Instituto de Educação & Universidade de Lisboa.

- Szabó, L., Zsolnai, A., & Fehérvári, A. (2024). The relationship between student engagement and dropout risk in early adolescence. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 6, Artigo 100328. [CrossRef]

- Van Canegem, T., Van Houtte, M., & Demanet, J. (2021). Grade retention and academic self-concept: A multilevel analysis of the effects of schools’ retention composition. British Educational Research Journal, 47(5), 1340–1360. [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, T. E., Moreira, P., Ulvseth, H., Andersson, H., Tetler, S., & Kuorelahti, M. (2018). Analyzing measurement invariance of the students’ engagement instrument brief version: The cases of Denmark, Finland, and Portugal. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 33(4), 297-313.

- Wang, M.-T., & Fredricks, J. A. (2014). The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Development, 85(2), 722–737. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).