1. Background of BlackBerry and Its Market Dominance in Early 2000s

BlackBerry, founded as Research in Motion (RIM) in 1984 by Mike Lazaridis and Douglas Fregin, transformed mobile communication in the early 2000s with secure email, QWERTY keyboards, and enterprise solutions (Seth, 2025). By 2009, it held 50% of the U.S. smartphone market, bolstered by BlackBerry Messenger’s encrypted messaging (Statista, 2017). Yet, its stock plummeted from $147 at its peak to $4.39 as of February 2025 (MarketBeat, 2025), reflecting its failure to counter touchscreen rivals like the iPhone (2007). For emerging tech firms, BlackBerry’s downfall underscores the necessity of adaptability. Its enterprise focus and resistance to consumer trends (Bali, 2025) led to its decline. Agility and consumer insight are vital in today’s volatile tech landscape.

This analyses critically examines BlackBerry’s decline by analysing its strategic failures, notably its inability to adapt to technological change, evolving consumer preferences, and intensifying competition. By applying Porter’s Five Forces, the Product Life Cycle Model, and Christensen’s Disruptive Innovation Theory, the analysis explores how competitive dynamics, market maturity, and disruptive technologies eroded BlackBerry’s market position. The findings provide key lessons on innovation, market responsiveness, and adaptability, offering practical insights for emerging technology firms aiming for sustained success in volatile, innovation-driven industries (Eisner et al., 2018).

2. Theoretical Framework Prespective

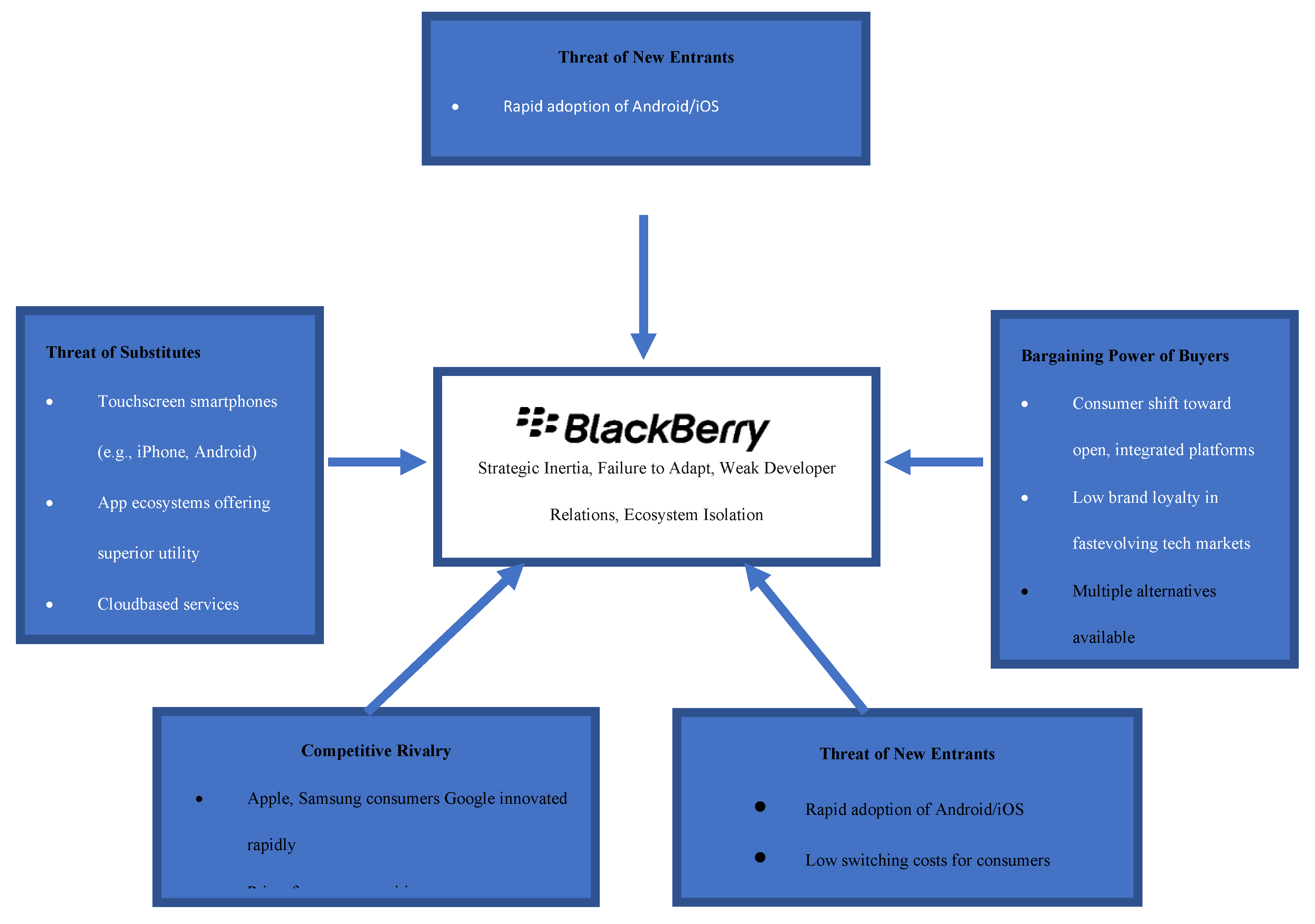

2.1. Porter’s Five Forces: Market Competitiveness and Threat Analysis

Michael Porter (1979) developed the Five Forces framework to assess industry competition, making it relevant for analyzing BlackBerry’s struggle against rising market pressures. The model helps explain how BlackBerry failed to respond to intense rivalry from Apple and Android, which capitalized on superior touchscreen technology and extensive app ecosystems (Schäfer, 2024). Additionally, Waworuntu et al. (2024) stresses that high consumer bargaining power, driven by increased smartphone alternatives, weakened BlackBerry’s market position. The model also highlights the threat posed by new entrants leveraging AI and cloud computing, which further marginalized BlackBerry. The failure to adapt to these forces ultimately contributed to its decline (Paksoy, Gunduz & Demir, 2023; Ndzabukelwako et al., 2024).

2.2. Product Life Cycle (PLC): Market Maturity and Decline

Raymond Vernon (1966) introduced the Product Life Cycle (PLC) theory, which is essential for understanding BlackBerry’s trajectory from dominance to decline. This model justifies how BlackBerry reached its maturity phase in the late 2000s but failed to innovate beyond its QWERTY keyboard and secure messaging services (George, & Baskar, 2024). As competitors advanced with touchscreen devices and app-based ecosystems, BlackBerry stagnated (De Streel & Larouche, 2024). The PLC model explains why failing to extend a product’s life cycle through continuous innovation leads to market exit, illustrating BlackBerry’s strategic misstep in not adapting to evolving consumer demands (Slater, 2023).

2.3. Christensen’s Disruptive Innovation Theory: Role of Innovation in Market Transformation

Clayton Christensen (1997) introduced the Disruptive Innovation Theory to explain how technological advancements can upend established industries. This model is crucial in understanding how BlackBerry was overtaken by disruptive innovations. While BlackBerry focused on incremental improvements for business users, Apple and Android redefined the market with user-friendly interfaces and vast app stores (Kolakaluri, 2022; Ge et al., 2023). BlackBerry’s inability to anticipate and respond to disruptive innovations highlights its failure to recognize shifting market trends. The theory underscores the importance of proactive innovation, a key lesson for emerging tech firms (Sarangdhar, Awate & Mudambi, 2024).

3. Market Position and Strategic Errors

BlackBerry’s failure to maintain market dominance is best understood as a result of compounded strategic errors rooted in misaligned positioning and an overconfidence in legacy strengths. Initially, BlackBerry built a defensible niche in the enterprise market by offering secure communication devices with robust email functionality (Seth, 2025). However, as the smartphone industry transitioned towards mass consumerism, BlackBerry’s inability or refusal to shift its strategic positioning became a fatal error (George & Baskar, 2024). From a Resource-Based View (RBV) perspective, BlackBerry possessed valuable internal capabilities—particularly its secure network infrastructure and proprietary OS. However, Cuthbertson and Furseth (2022), Rao and Brown (2024) and Hari, Subramaniam and Dileep (2014) argued that it failed to transform these into sustainable competitive advantages as consumer preferences evolved. Cheng (2024) notes that strategic misjudgement was evident in the overcommitment to physical keyboards and enterprise clients, despite clear market signals favouring touchscreen devices and app ecosystems. As Alzaydi (2024) notes, firms that cling to outdated design paradigms in high-velocity environments face rapid obsolescence.

This brings into question BlackBerry's strategic foresight. Porter (2008) warns that firms must continuously reconfigure their value propositions in response to evolving Five Forces dynamics. Paksoy et al. (2023) and Vassolo, Weisz and Laker (2024) highlight Blackberry did not heed these pressures, particularly the threat of substitutes and the rising bargaining power of consumers, who gravitated towards more user-friendly devices offered by Apple and Samsung. This was not merely a tactical lapse but a deeper strategic inertia, wherein organisational commitment to a past success formula hindered innovation (Sarkar & Osiyevskyy, 2018; George & Baskar, 2024). Contrary perspectives argue that BlackBerry’s decision to maintain a focus on enterprise security was not entirely misguided, particularly given the growing corporate concern over data breaches. However, Christensen’s disruptive innovation theory (1997) contests this view by asserting that market incumbents often fail because they neglect the broader shifts initiated by entrants targeting underserved or emerging market needs. This theory underscores that BlackBerry's tunnel vision on enterprise clients excluded the emerging mass consumer segment, allowing disruptors to gain dominance.

Furthermore, the strategic drift framework (Johnson et al., 2017) is instructive in understanding BlackBerry’s disconnect between internal strategy and external market shifts. Despite declining market share, BlackBerry persisted in strategies that no longer aligned with the realities of consumer demand, reflecting classic drift symptoms. It also ignored critical inflection points, such as the launch of Apple’s iPhone in 2007 and Android’s open-source rise, which industry peers such as Samsung swiftly embraced (Song et al., 2016).

4. Innovation Myopia and Technology Resistance

BlackBerry’s demise is often attributed not to a lack of innovation per se, but rather to innovation myopia; a form of strategic blindness where firms innovate within familiar paradigms while failing to anticipate or embrace transformative shifts. This aligns with Christensen’s (1997) claim that successful companies often lose market share by prioritising sustaining innovations over disruptive ones. Innovation myopia at BlackBerry manifested in several forms. The company continued to enhance its QWERTY keyboard and security features while competitors prioritised user experience, touchscreen design, and app-driven ecosystems (Cheng, 2024; Bharath and Damodhar, 2023). From the perspective of Exploration vs. Exploitation Theory (March, 1991), BlackBerry over-invested in exploiting known competencies rather than exploring new domains such as mobile applications, intuitive UX, or third-party integration. This strategic bias contributed to a culture of risk aversion, as also reflected in the rejection of Android OS integration and delayed transition to touchscreen models (Chen, 2023; George and Baskar, 2024).

A counterargument may posit that BlackBerry’s conservative approach was an attempt to avoid alienating its enterprise client base. However, this raises critical questions: Should loyalty to a legacy user group outweigh market trends? Can technological leadership be sustained without public adoption? Evidence suggests that failure to evolve technologically alienated not only consumers but also developers, as BlackBerry’s restrictive OS limited software integration, leaving it isolated in a networked market (Mundra and Bajj, 2025; Priyanka, 2023).

This isolation contradicts the principles of platform ecosystem theory, which posits that innovation today is less about individual products and more about ecosystems of interoperable services (Cennamo, 2021). In a market where Apple and Google were cultivating developer ecosystems, BlackBerry’s closed approach was interpreted as a refusal to democratise innovation, a position untenable in the era of open platforms and crowd-sourced creativity.

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) further illuminates BlackBerry’s oversight. Perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are core to adoption. BlackBerry’s devices, with complex interfaces and limited app stores, fell short on both dimensions. Meanwhile, competitors like Apple simplified smartphone interaction through capacitive touchscreens and intuitive design, making their devices more appealing to average consumers (Britton, Setchi, and Marsh, 2013; Nam et al., 2021; Caminade & Borck, 2023). A similar pattern of innovation resistance contributed to Nokia’s parallel decline, illustrating the broader relevance of these findings (Hari, Subramaniam and Dileep, 2014). Both firms underestimated the rate at which consumer behaviour and technological infrastructure were evolving. In contrast, Samsung’s success, driven by rapid adoption of Android and relentless R&D, exemplifies the importance of embracing not resisting technological change (Haizar et al., 2020; Boccarossa, 2018).

Arguably, innovation myopia at BlackBerry was compounded by a culture that privileged technological perfection over market responsiveness. As Day (2025) argues, innovation must be iterative and market-driven, not insulated within engineering departments. BlackBerry’s internal reluctance to question its legacy strengths further reveals a lack of intrafirm dissent and strategic flexibility, symptoms of what Mintzberg (1994) described as the perils of ‘planning paralysis’.

5. Competitive Landscape and Market Forces

BlackBerry’s decline can be analyzed using Porter’s Five Forces Model, which evaluates industry competitiveness. BlackBerry’s strategic rigidity prevented it from adapting to market changes, making it vulnerable to competitors (Georg & Baskar, 2024).

5.1. Application of Porter’s Five Forces

5.1.1. Threat of Substitutes: The Rise of Multifunctional Smartphones

BlackBerry’s initial success stemmed from secure messaging and enterprise tools, but it failed to adapt as smartphones evolved. Apple and Android devices integrated touchscreen keyboards, cloud security, and superior communication apps, rendering BlackBerry’s physical keyboard obsolete (Seth, 2025). Christensen, Raynor, and McDonald (2015) argue that disruptive innovation replaces outdated technologies when it offers better functionality and accessibility precisely what iOS and Android achieved. BlackBerry’s failure to transition from niche enterprise products to mainstream consumer-friendly smartphones accelerated its decline (Bresnahan, Davis & Yin, 2014).

5.1.2. Bargaining Power of Buyers: Consumer Shift to Open Ecosystems

Consumers preferred interoperability and digital integration, leading to demand for open ecosystems (Kerber & Schweitzer, 2017). BlackBerry’s closed system and proprietary software limited third-party app development, isolating users. Cennamo, (2021) highlight that firms thriving in digital markets prioritize platform-based business models. BlackBerry’s rigid approach alienated consumers, whereas Apple and Google fostered developer-friendly platforms, driving customer retention (Cheng, 2024).

5.1.3. Competitive Rivalry: Rapid Innovation from Apple, Samsung, and Google

The smartphone industry became highly competitive, requiring firms to innovate continuously or risk obsolescence (Alzaydi, 2024; Barros & Dimla, 2021). Apple and Samsung led the market with touchscreens, superior processing power, and app-driven ecosystems, while BlackBerry resisted change (Walling, 2014). Samsung, unlike BlackBerry, adapted quickly, diversifying its product line across premium and budget segments (Schäfer, 2024). This contrast underscores the risks of failing to align innovation with consumer preferences, reinforcing disruptive innovation theory (George & Baskar, 2024).

5.1.4. Failure to Build Developer Partnerships

BlackBerry’s restrictive policies deterred developers, leading to an app shortage. In contrast, Apple’s App Store (2008) and Google’s Play Store (2012) fostered thriving developer ecosystems, enhancing user experience (Anderson & Tushman, 2017). Samsung leveraged Android’s open-source model, securing thousands of app integrations, while BlackBerry’s refusal to fully integrate with Android weakened its market position (European Commission, 2018). Walton, (2021) emphasize that platform-based innovation is critical in modern technology markets, a factor BlackBerry underestimated.

5.1.5. Strategic Comparison: BlackBerry vs. Nokia and Samsung

BlackBerry’s decline parallels Nokia’s failure, as both companies prioritized hardware over software innovation, losing to ecosystem-driven competitors (Thompson, 2013). Porter’s (2008) theory underscores that market leaders who fail to recognize industry shifts face rapid decline.

Samsung, by contrast, embraced Android, diversified its products, and consistently innovated, ensuring its dominance (Song, Lee & Khanna, 2016). This comparison highlights that strategic flexibility and ecosystem-driven innovation are essential for long-term success (Ghezzi et al.,2015).

Figure 1.

Application of Porter’s Five Forces to the Strategic Decline of BlackBerry.

Figure 1.

Application of Porter’s Five Forces to the Strategic Decline of BlackBerry.

6. Leadership, Culture, and Organizational Inertia

BlackBerry’s decline can be examined through the lens of Strategic Drift Theory, which explains how organizations gradually lose alignment with their external environment due to internal inertia (Sarta, 2021; Krabbe & Grodal, 2023). This phenomenon was evident in BlackBerry’s decision-making structure, risk-averse culture, and misaligned leadership priorities, which collectively hindered the company's ability to compete in the evolving smartphone market.

6.1. Internal Decision-Making Structure and Executive Overconfidence

One of BlackBerry’s critical missteps was its rigid, top-down decision-making structure, which discouraged adaptability. The company’s executives, including co-CEOs Jim Balsillie and Mike Lazaridis, held a deep-seated belief in BlackBerry’s superiority, leading to overconfidence in its existing business model (Takahashi, 2012). This executive complacency is characteristic of organisational inertia, where leadership remains resistant to market shifts due to past success (Sarkar & Osiyevskyy, 2018; Rusetski & Lim, 2011). While Apple and Google rapidly innovated, BlackBerry’s leadership dismissed touchscreen smartphones as a passing trend, underestimating the impact of the iPhone’s introduction in 2007 (Christensen, Raynor, & McDonald, 2015).

6.2. Risk-Averse Culture and Rejection of Consumer Trends

BlackBerry’s internal culture prioritised security and reliability, which made it dominant in the enterprise sector. However, this conservative approach made the company resistant to consumer-driven changes, such as the demand for intuitive user interfaces and touchscreen devices (Fairfield, 2018). Unlike Apple and Samsung, which embraced user-friendly designs, BlackBerry clung to physical keyboards, assuming its business customers would remain loyal (Pitt, 2023). According to Kotler and Keller (2020), successful firms align with shifting consumer preferences rather than dictating market trends, a lesson BlackBerry failed to apply.

6.3. Misaligned Leadership Priorities: Protecting Enterprise Reputation Over Innovation

Another factor contributing to BlackBerry’s decline was its overemphasis on protecting its enterprise reputation rather than expanding into the broader consumer market. While competitors diversified their strategies to attract mass-market consumers, BlackBerry maintained its enterprise-first philosophy, limiting its market reach (BlackBerry, 2021). This approach reflects strategic drift, where firms fail to evolve with changing industry dynamics, ultimately leading to decline (Sammut-Bonnici, 2015).

6.4. Missed Acquisition Opportunities and Failure to Adopt Android

A pivotal miscalculation in BlackBerry’s strategy was its reluctance to adopt Android as an operating system. Unlike Samsung, which leveraged Android’s flexibility to drive market penetration, BlackBerry insisted on its proprietary software, limiting third-party application development (Chen, 2023). Additionally, BlackBerry missed key acquisition opportunities that could have bolstered its technological capabilities, further illustrating the dangers of strategic rigidity (George, & Baskar, 2024).

7. Implications for Emerging Tech Firms

Building on this critical analysis of BlackBerry’s strategic missteps, the following section outlines key lessons for emerging technology firms. By analysing BlackBerry’s missteps, startups and scaleups can adopt strategies that prioritise agility, ecosystem thinking, and proactive innovation to sustain competitive advantage.

7.1. Lesson 1: Agility and Consumer-Centric Design

A key factor in BlackBerry’s downfall was its reluctance to prioritise consumer demands over enterprise security. Emerging firms must recognise that consumer preferences evolve rapidly, and failing to adapt can lead to obsolescence (Alzaydi, 2024). Agility in product development, based on user feedback and market trends, is essential. As Christensen (1997) argued in The Innovator’s Dilemma, market incumbents often focus on existing customer needs at the expense of emerging demands, allowing disruptive innovators to gain a foothold. Furthermore, Companies such as Apple and Google have thrived by prioritising seamless user experiences, whereas BlackBerry’s commitment to physical keyboards and closed systems alienated potential consumers (Cheng, 2024).

7.2. Lesson 2: Ecosystem Thinking

Modern technology markets are increasingly platform-driven rather than product-driven. BlackBerry’s refusal to build a strong developer ecosystem significantly weakened its competitive standing. In contrast, Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store created extensive software ecosystems that enhanced user engagement and retention (Statista, 2024; Caminade & Borck, 2023). Emerging tech firms should invest in building robust platforms by providing APIs and SDKs that enable third-party innovation. As Porter (2008) highlights, competitive advantage is sustained when firms integrate into a broader network of complementary products and services. Samsung’s success, for example, stemmed from its strategic alignment with Android’s open-source ecosystem, ensuring widespread app compatibility (Haizar et al., 2020).

7.3. Lesson 3: Strategic Foresight and Innovation Culture

BlackBerry’s failure to anticipate the touchscreen revolution exemplifies the risks of reactive rather than proactive strategy. Emerging tech firms must adopt strategic foresight to identify disruptive technologies early. This involves monitoring weak signals in market behavior and investing in R&D to create adaptable business models (Schneckenberg et al., 2017). According to Shamsub, (2023) companies that fail to cultivate an innovation-driven culture struggle to compete in rapidly evolving industries. BlackBerry’s leadership resisted necessary changes, whereas firms like Tesla and Amazon continuously disrupt their own business models to maintain relevance.

7.4. Practical Recommendations for Startups and Scaleups

To avoid BlackBerry’s fate, emerging firms should:

Embrace flexible business models – Companies must iterate quickly based on user feedback and technological advancements.

Monitor weak signals in market behavior – Investing in data analytics and trend forecasting can help firms detect shifts before competitors.

Invest in ecosystem development – Providing APIs and fostering developer communities ensures long-term platform viability (Wang, 2024).

By integrating these lessons, emerging tech firms may navigate market disruptions and build sustainable competitive advantages.

8. Conclusion

BlackBerry’s decline highlights the dangers of strategic rigidity and resistance to innovation. The company's overreliance on enterprise customers, reluctance to embrace touchscreen technology, and failure to develop a strong app ecosystem significantly weakened its competitive position. As Porter’s Five Forces and the Product Life Cycle Model illustrate, firms that ignore market shifts risk obsolescence. The case of BlackBerry reveals the necessity of agility, ecosystem thinking, and continuous innovation. For emerging tech firms, success depends on strategic foresight, adaptability, and a consumer-centric approach, ensuring long-term market relevance in rapidly evolving industries.

References

- Alzaydi, A. Balancing creativity and longevity: The ambiguous role of obsolescence in product design. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, V. (2025, March 21). BlackBerry’s decline: A case study in the smartphone market’s rapid evolution. Cognitive Market Research. https://www.cognitivemarketresearch.com.

- Barros, M.; Dimla, E. FROM PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE TO THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY IN THE SMARTPHONE INDUSTRY: AN EVOLUTION OF STRATEGIES EMBODIED IN PRODUCT FEATURES. Proc. Des. Soc. 2021, 1, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, P.; Damodhar, D.B. From leader to laggard: An analysis of Blackberry's UI/UX missteps and the decline of a tech giant. Milestone Transactions on Futuristic Engineering 2023, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- BlackBerry. (2021). Code of business standards and principles. BlackBerry Limited. https://www.blackberry.com/content/dam/blackberry-com/Documents/pdf/corporate-responsibility/Code_of_Business_Standards_and_Principles.

- Boccarossa, L. (2018). Changes in leadership in the mobile phone industry: The case of Asian handset firms catching-up.

- Bresnahan, T. F. , Davis, J. P., & Yin, P. L. (2014). Economic value creation in mobile applications. In The changing frontier: Rethinking science and innovation policy (pp. 233–286). University of Chicago Press.

- Britton, A. , Setchi, R., & Marsh, A. (2013). Intuitive interaction with multifunctional mobile interfaces. Journal of King Saud University – Computer and Information Sciences, 25(2), 187–196.

- Caminade, J. , & Borck, J. (2023). The continued growth and resilience of Apple's App Store ecosystem. Analysis Group. https://www.apple.com/newsroom/pdfs/the-continued-growth-and-resilience-of-apples-app-store-ecosystem.

- Cennamo, C. Competing in Digital Markets: A Platform-Based Perspective. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 35, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Corporate innovation ecosystem based on core competence case study—International part. In Enterprise Innovation Ecosystem: Theory and Practice (pp. 183–261). Springer Nature Singapore, 2023.

- Cheng, Y. Transformation Journey of Blackberry: From Mobile Communications to Network Security Giant. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 35, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C. M.; Raynor, M. E.; McDonald, R. What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review 2015, 93, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson, R.W.; Furseth, P.I. Digital services and competitive advantage: Strengthening the links between RBV, KBV, and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. Diagnosing the Market-Driven Approach to Innovation: Learning from Practice. Strat. Manag. Rev. 2025, 6, 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Streel, A., & Larouche, P. (2024). Disruptive innovation and antitrust. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4906842.

- Eisner, A. , Nazir, S., Korn, H., & Baugher, D. (2018). BLACKBERRY LIMITED: IS THERE A PATH TO RECOVERY? Global Journal of Business Pedagogy, 2(1).

- European Commission. (2018). Commission decision of 18 July 2018 relating to a proceeding under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement (AT.40099 – Google Android).

- Fairfield, J. A. (2018). Mixed reality: How the laws of virtual worlds govern everyday life. In Research Handbook on the Law of Virtual and Augmented Reality (pp. 103–152). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ge, Y. , Ren, Y., Hua, W., Xu, S., Tan, J., & Zhang, Y. (2023). LLM as OS, agents as apps: Envisioning AIOS, agents and the AIOS-agent ecosystem. arXiv:2312.03815.

- George, A. S.; Baskar, T. Riding the wave: How incumbents can surf disruption caused by emerging technologies. Partners Universal International Research Journal 2024, 3, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi, A.; Cavallaro, A.; Rangone, A.; Balocco, R. On business models, resources and exogenous (dis)continuous innovation: evidences from the mobile applications industry. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2015, 68, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haizar, N.F.B.M.; Kee, D.M.H.; Chong, L.M.; Chong, J.H. The Impact of Innovation Strategy on Organizational Success: A Study of Samsung. Asia Pac. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 3, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, A.P.N.; Subramaniam, S.R.; Dileep, K.M. (2014). Impact of innovation capacity and anticipatory competence on organizational health: A resource-based study of Nokia, Motorola and Blackberry. International Journal of Economic Research, 11(2), 395–415.

- Johnson, G.; Scholes, K.; Whittington, R. (2017). Exploring strategy: Text and cases (11th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Kerber, W.; Schweitzer, H. (2017). Interoperability in the digital economy. J. Intell. Prop. Info. Tech. & Elec. Com. L., 8, 39.

- Kolakaluri, V. N. S. K. (2022). New modern marketing myopia: A clouded innovation and stigmatized marketing.

- Krabbe, A.D.; Grodal, S. The Aesthetic Evolution of Product Categories. Adm. Sci. Q. 2023, 68, 734–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87.

- MarketBeat. (2025). BlackBerry (BB) stock forecast and price target 2025. https://www.marketbeat.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning. Free Press.

- Mundra, R.; Bajj, A. (2025). Why BlackBerry failed: Lessons in technological evolution. StartupTalky. https://startuptalky.com/why-blackberry-failed/.

- Nam, H.; Seol, K.-H.; Lee, J.; Cho, H.; Jung, S.W. Review of Capacitive Touchscreen Technologies: Overview, Research Trends, and Machine Learning Approaches. Sensors 2021, 21, 4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndzabukelwako, Z.; Mereko, O.; Sambo, T.; Thango, B. (2024). The impact of Porter's five forces model on SMEs performance: A systematic review. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4999059.

- Paksoy, T.; Gunduz, M.A.; Demir, S. Overall competitiveness efficiency: A quantitative approach to the five forces model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, G. (2023). Be present: Why it's time to control your digital habits. FPG Publishing.

- Porter, M.E. How competitive forces shape strategy. Harvard Business Review 1979, 57, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Priyanka. (2023). Why BlackBerry failed? An introspective look at the rise and fall of the iconic smartphone brand. Tactyqal. https://tactyqal.com/blog/why-blackberry-failed/.

- Rao, A.; Brown, M. A review of the resource-based view (RBV) in strategic marketing: Leveraging firm resources for competitive advantage. Business, Marketing, and Finance Open 2024, 1, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rusetski, A.; Lim, L.K. Not complacent but scared: another look at the causes of strategic inertia among successful firms from a regulatory focus perspective. J. Strat. Mark. 2011, 19, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammut-Bonnici, T. (2015). Strategic drift. In Wiley encyclopedia of management (Vol. 12: Strategic Management). Wiley.

- Sarangdhar, V.; Awate, S.; Mudambi, R. Business model innovations in high-velocity environments. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Osiyevskyy, O. Organizational change and rigidity during crisis: A review of the paradox. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarta, A. (2021). Refining adaptation and its onset: Signals of financial innovation that trigger strategic attention in financial services. [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Western Ontario (Canada)].

- Schäfer, P. (2024). Conditions of the international smartphone market—Analysing the US market (Master's thesis, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa (Portugal)).

- Schneckenberg, D.; Velamuri, V.K.; Comberg, C.; Spieth, P. Business model innovation and decision making: uncovering mechanisms for coping with uncertainty. R&D Manag. 2016, 47, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, S. (2025). BlackBerry: A story of constant success and failure. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/062315/blackberry-story-constant-success-failure.

- Shamsub, H. (2023). Innovator’s advantage: Disruptive business model for the future. Arisia.

- Slater, J. (2023, ). What every company is dying to know about product life cycle. The Marketing Sage.

- Song, J.; Lee, K.; Khanna, T. Dynamic Capabilities at Samsung: Optimizing Internal Co-Opetition. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 118–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2017). The terminal decline of BlackBerry. https://www.statista.com/chart/8180/blackberrys-smartphone-market-share/.

- Statista. (2024). Apple App Store – statistics & facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/9757/apple-app-store/.

- Takahashi, D. (2012, January 22). BlackBerry’s leadership fail: The symbol of software’s triumph over hardware. VentureBeat.

- Thompson, B. (2013, August 12). BlackBerry – and Nokia's – fundamental failing. Stratechery.

- Vassolo, R.S.; Weisz, N.; Laker, B. (2024). Race against time: Staying agile in rapidly developing industries. In Advanced strategic management: A dynamic approach to competition (pp. 69–82). Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Vernon, R. International Investment and International Trade in the Product Cycle. Q. J. Econ. 1966, 80, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, D. R. (2014). Designing learning for tablet classrooms: Innovations in instruction. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Walton, N. (2021). Entrepreneurs, platforms, and international technology transformation. In Empirical international entrepreneurship: A handbook of methods, approaches, and applications (pp. 61–85).

- Wang, J.S. Exploring and evaluating the development of an open application programming interface (Open API) architecture for the fintech services ecosystem. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2024, 30, 1564–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Connecting the Parts with the Whole: Toward an Information Ecology Theory of Digital Innovation Ecosystems. MIS Q. 2021, 45, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waworuntu, E.C.; Yasuwito, M.; Sumanti, E. Analyzing global industry dynamics using Porter’s five forces and ratio analysis model. Jurnal Ekonomi 2024, 13, 745–760. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. S. , Tonsukchai, G., Chatpokponjaroon, P., Wu, C. Y., & Molina, M. F. D. Ahead of the curve: The strategic analysis of Samsung.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).