Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Study

2.1. Problem Statement

2.2. Justification of the Study

3. Literature Review

3.1. Theoretical Literature Review

3.2. Empirical Literature Review

4. Methodology

4.1. Variable Description

Renewable Energy Supply (RES)

Income Level

Remittances

Public Private Partnerships

ZESA Reliability

Education Level

Trade Openness

Foreign Direct Investment

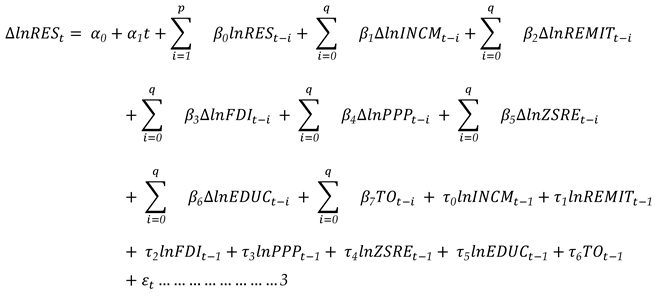

4.2. ADRL Model Specification

Error Correction Model

4.3. Pre- and Post-Diagnostic Tests

5. Presentation and Analysis of Findings

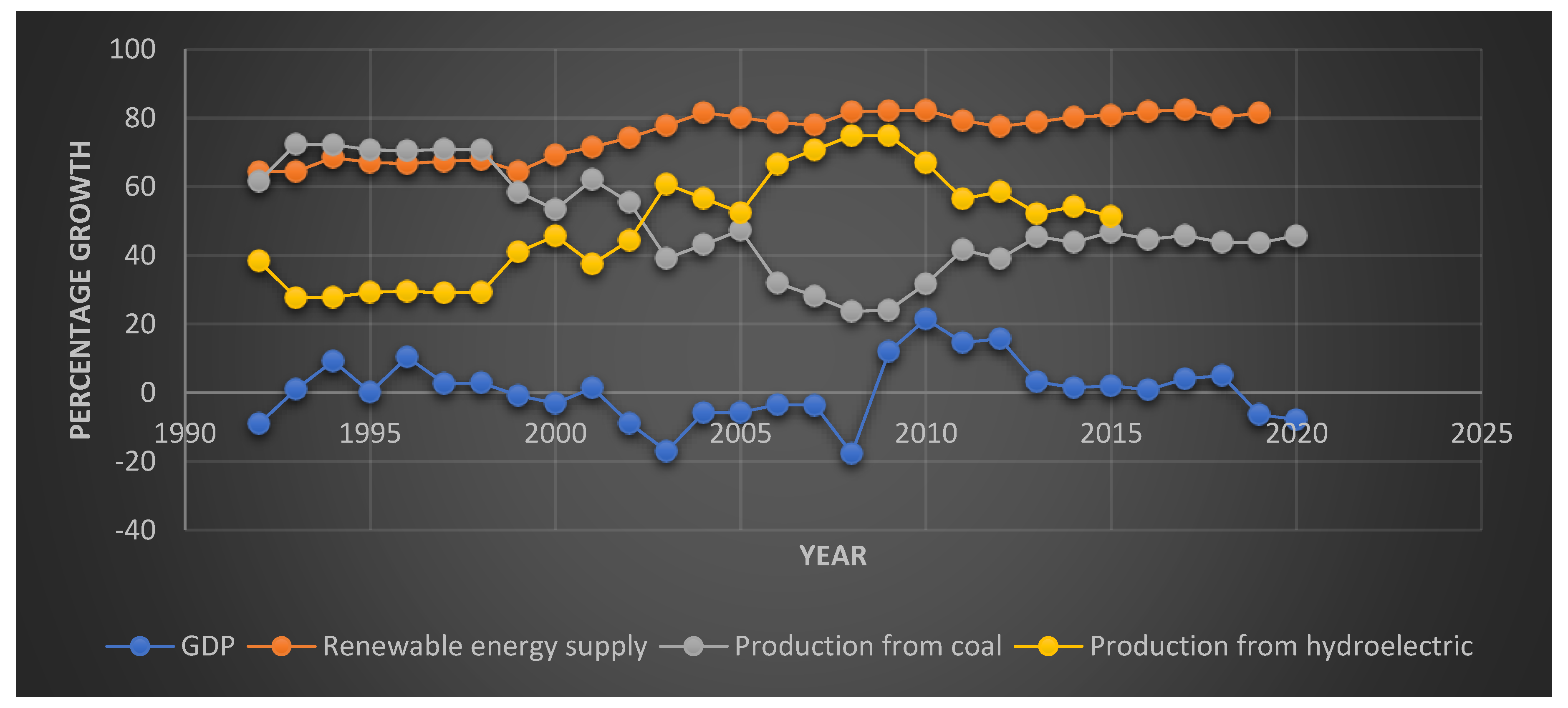

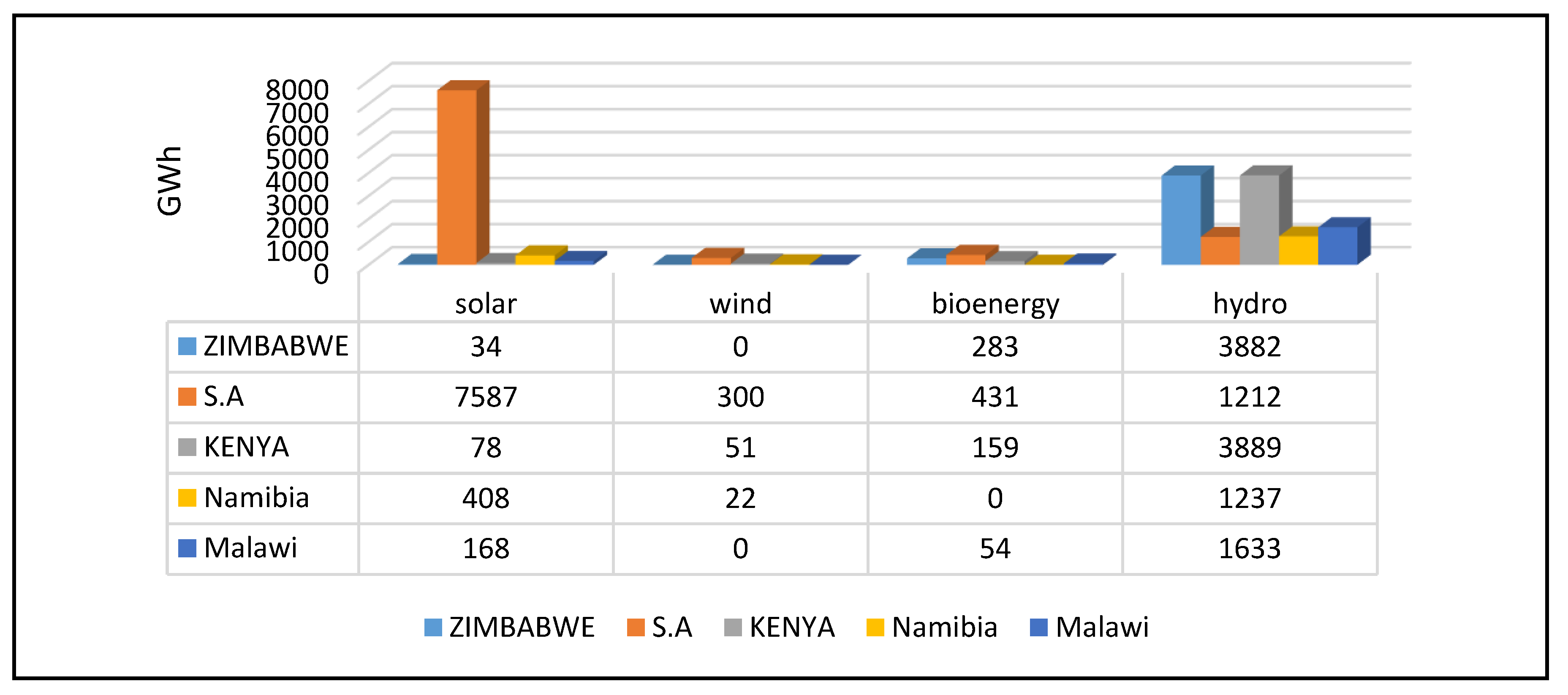

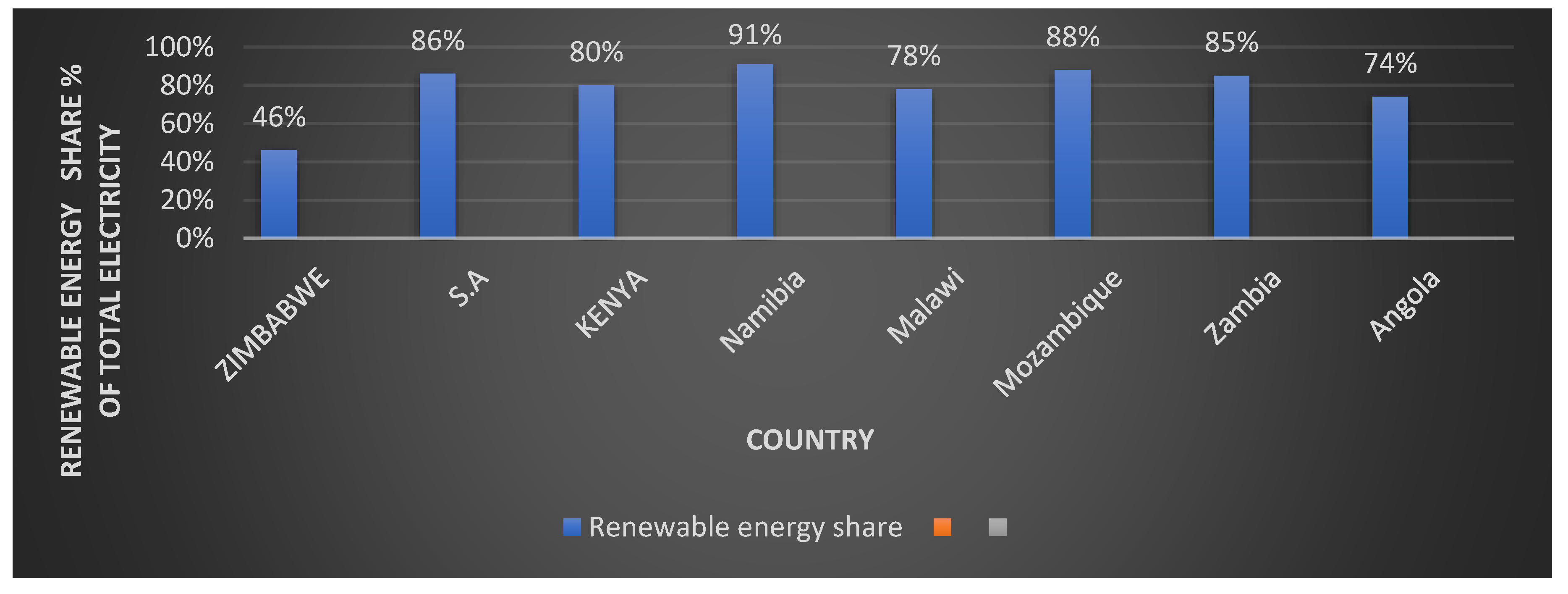

5.1. Determining Renewable Energy Potential in Zimbabwe

5.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.4. Multicollinearity Test

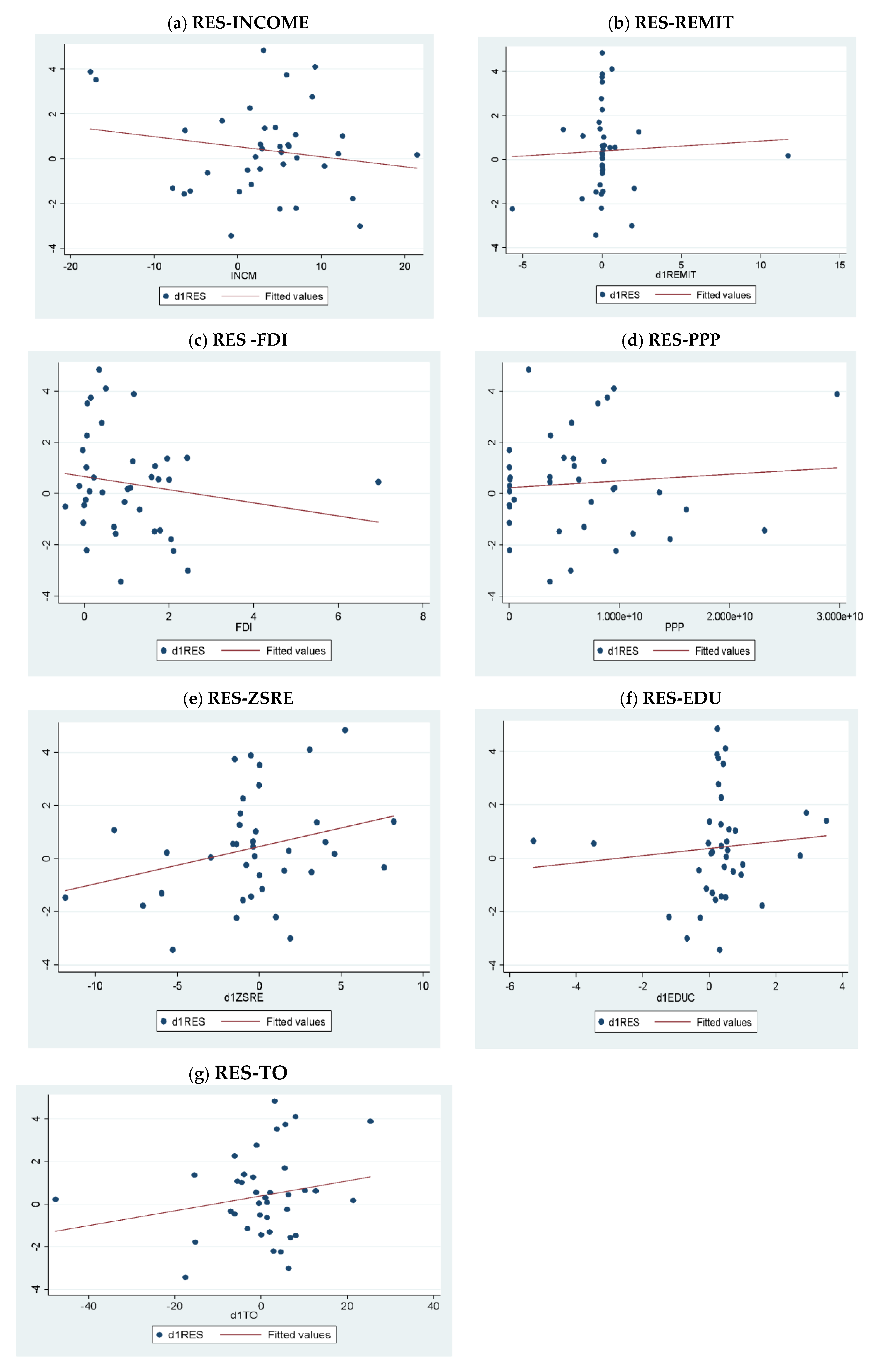

4.4. Graphical Relatiosnhip

- (a)

- There is a moderate negative linear relationship between renewable energy supply and income level.

- (b)

- There is a weak positive linear relationship between renewable energy supply and remittances.

- (c)

- There is a weak negative linear relationship between renewable energy supply and FDI.

- (d)

- There is a weak positive linear relationship between renewable energy supply and public private partnership investments.

- (e)

- There is a weak positive linear relationship between renewable energy supply and ZESA reliability.

- (f)

- There is a weak positive linear relationship between renewable energy supply and education level.

- (g)

- There is a moderate positive linear relationship between renewable energy supply and trade openness.

4.6. ARDL REGRESSION RESULTS

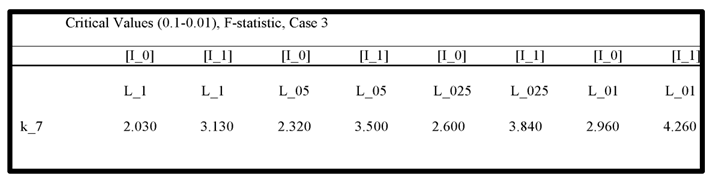

5.2.1. Testing for Cointergration

5.2.2. Error Correction Model

5.3. Interpretation of the Error Correction Model Findings

5.3.1. Long Run Impact of Variables

5.3.2. Short Run Impact of Variables

6. Summary, Conclusion and Policy Recommendation

6.1. Policy Implications

Improve Systems of Cross Border Migration

Embark on Awareness Programs

Facilitate the Production Renewable Energy in Short Run

Prioritize Renewable Energy Production in the Long Run

Attract Large Public Private Partnership Investments (PPP)

6.2. Areas for Further Study

References

- Akintande, A., (2020). Modeling the determinants of renewable energy consumption: Evidence from the five most populous nations in Africa. Energy Journal, Volume, 206, pp117992, issn: 0360-5442. [CrossRef]

- Au, Y. A, & Zafar, H. (2008). A Multi-Country Assessment of Mobile Payment Adoption. In Working Paper SERIES.

- Bourcet C. (2020). Empirical determinants of renewable energy deployment: A systematic literature review. Energy Economics. Vol 85, pp 104563.

- Chen, L. Da, & Tan, J. (2004). Technology adaptation in E-commerce: Key determinants of virtual stores acceptance. European Management Journal. [CrossRef]

- Caver,N., (2023). Climate change and its Impact: Energy Outlook and Energy Saving Potential in East Asia 2020, Jakarta.

- Chipango, E.F., (2021). Why renewable energy won’t end energy poverty in Zimbabwe. Academic rigour, journalistic flair.

- s, A.K., McFarlane, A., & Carels, L. (2021). Empirical exploration of remittances and renewable energy consumption in Bangladesh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 5, 65 - 89.

- Doytch, N., & Narayan, S.W. (2016). Does FDI influence renewable energy consumption? An analysis of sectoral FDI impact on renewable and non-renewable industrial energy consumption. Energy Economics, 54, 291-301.

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Chen, H., & Williams, M. D. (2011). A meta-analysis of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). IFIP Advances in Information and Communication. [CrossRef]

- Fatima N, Li Y, Ahmad M, Jabeen G, Li X. Factors influencing renewable energy generation development: a way to environmental sustainability. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021 Oct;28(37):51714-51732. . Epub 2021 May 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Zimbabwe (2022). Zimbabwe’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) Submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/Zimbabwe%20First%20NDC.pdf.

- Government of Zimbabwe (2019). National Adaptation Plan: Roadmap for Zimbabwe. https://napglobalnetwork.org/resource/national-adaptation-plan-nap-roadmap-for-zimbabwe/.

- International Renewable Energy Agency (2022). Energy Profile Zimbabwe: https://www.irena.org//media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Statistics/Statistical_Profiles/Africa/Zimbabwe_Africa_RE_SP.pdf.

- Jean, T. (2020). “Zimbabwe: Tatanga and Sable Chemicals agree on a 50 MWp solar power station”. Paris, France: Afrik21.africa.

- Jean, M.T. (2022). “Zimbabwe: Kibo Energy takes over 100 MWp solar project in Victoria Falls”. Afrik21.africa. Paris, France.

- Kamalad, S. (2021), ‘Thailand Country Report’, in Han, P. and S. Kimura (eds.), Energy Outlook and Energy Saving Potential in East Asia 2020, Jakarta: ERIA, pp.270-280.

- Makonese, T. (2016). Renewable energy in Zimbabwe. Research Gate. 1-9. 10.1109/DUE.2016.7466713.

- Mita, B., Sefa A.C., Sudharshan, R.P. (2017). The dynamic impact of renewable energy and institutions on economic output and CO2 emissions across regions, Renewable Energy,Volume 111, Pages 157-167, ISSN 0960-1481, . [CrossRef]

- Murshed M. (2020). An empirical analysis of the non-linear impacts of ICT-trade openness on renewable energy transition, energy efficiency, clean cooking fuel access and environmental sustainability in South Asia. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. Vol (29). [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Energy and Power Development (2019). National Renewable Energy Policy. Zimbabwe-RE-Policy-2019.pdf (acecdn.net).

- Ministry of Energy and Power Development (2019). Independent Power Producers: National Renewable Energy Policy. Zimbabwe-RE-Policy-2019.pdf (acecdn.net).

- Mbohwa, C (2023). Zimbabwe: An Assessment of the Electricity Industry and What Needs to Be Done. The Electricity Journal. Vol15,(7). Pg 82-91. ISSN 1040-6190. [CrossRef]

- Oshlyansky, L., Cairns, P., & Thimbleby, H. (2007). Validating the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) tool cross-culturally. People and Computers XXI HCI.But Not as We Know It - Proceedings of HCI 2007: The 21st British HCI Group Annual Conference, 2(September). [CrossRef]

- Omri A. and Nguyen D. K. (2014). On the determinants of renewable energy consumption: International evidence. Energy. Vol (72), 1, Pages 554-560.

- Omoju E. O., Okonkwo U. J. and Lin B. (2020). Factors influencing renewable electricity consumption in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. Vol 55, Pages 687-696.

- Robert, T. (2021). “Belarus Investors Win Tender For 100 Megawatt Solar Plant”. NewZimbabwe.com. Harare.

- Subramaniam, Y., Masron, T.A., & Loganathan, N. (2022). Remittances and renewable energy: an empirical analysis. International Journal of Energy Sector Management.

- Sisodia G.S, Soares I. (2015). Panel data analysis for renewable energy investment determinants in Europe. Applied Economics Letters, 22(5), 397-401.

- Sisodia et al.(2015). Does the use of Solar and Wind Energy Increase Retail Prices in Europe? Evidence from EU-27. Energy Procedia vol 79 pp506 – 51.

- Schillewaert, N., Ahearne, M. J., Frambach, R. T., & Moenaert, R. K. (2005). The adoption of information technology in the sales force. Industrial Marketing Management.

- World Bank. (2023). Indicators | Data (worldbank.org).

- United Nations (2023). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report | UNEP - UN Environment Programme.

- United Nations (2022). COP27: Delivering for people and the planet | United Nations: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop27.

- Venkatesh, V. (2016). The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A SYNTHESIS AND THE ROAD AHEAD. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 17(5), 328– 376. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Mingming & Zhang, Shichang & Lee, Chien-Chiang & Zhou, Dequn, 2021. Effects of trade openness on renewable energy consumption in OECD countries: New insights from panel smooth transition regression modelling. Energy Economics, Elsevier, vol. 104(C).

| Solar power station | Province | Owner of station | Capacity (Megawatts) | Electricity Generated (Megawatts)in 2018 | |

| Chiredzi solar power | Masvingo | Triangle solar system | 90 | 90 | |

| Collen Bawn Solar power station | Matebeleland south | Pretoria Portland Cement | 32 | 32 | 16MW to be sold to ZETDCL |

| Kwekwe solar power station | Midlands | Kwekwe Energy Power | 50 | 50 | |

| Norton solar power station | Mashonaland south | Norton solar company | 100 | 100 | Energy to be sold to ZETDCL. |

| Umguza solar power station | Matebeleland North | AF power private limited | 200 | 200 | |

| Victoria falls solar power station | Matebeleland North | Kibo energy Plc | 100 | 100 |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| RES | 40 | 72.302 | 7.733 | 62.378 | 82.46 |

| INCM | 40 | 3.557 | 7.879 | -17.669 | 21.452 |

| REMIT | 40 | 2.735 | 4.491 | .004 | 13.611 |

| FDI | 40 | .972 | 1.274 | -.453 | 6.94 |

| PPP | 40 | 6059000000 | 6585000000 | 7300000 | 29730000000 |

| ZSRE | 40 | 62.777 | 5.138 | 47.252 | 71.9 |

| EDUC | 40 | 81.846 | 4.218 | 72.326 | 88.693 |

| TO | 40 | 63.184 | 16.804 | 35.917 | 109.522 |

| Variable |

ADF p-value@ level |

ADF p-value @ first difference |

Order of integration |

| RES | 0.8354 | 0.0000 | I(1) |

| INCM | 0.0002 | - | I(0) |

| REMIT | 0.6114 | 0.0000 | I(1) |

| FDI | 0.0010 | - | I(0) |

| PPP | 0.0107 | - | I(0) |

| ZSRE | 0.4097 | 0.0000 | I(1) |

| EDUC | 0.3222 | 0.0000 | I(1) |

| TO | 0.1771 | 0.0000 | I(1) |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| (1) INCM | 1.000 | ||||||

| (2) d1REMIT | 0.264 | 1.000 | |||||

| (3) FDI | 0.033 | -0.066 | 1.000 | ||||

| (4) PPP | -0.364 | 0.025 | 0.240 | 1.000 | |||

| (5) d1ZSRE | 0.152 | 0.205 | -0.099 | -0.148 | 1.000 | ||

| (6) d1EDUC | -0.048 | -0.053 | -0.110 | -0.003 | 0.072 | 1.000 | |

| (7) d1TO | -0.226 | 0.314 | 0.010 | 0.136 | 0.243 | -0.120 | 1.000 |

| d1RES | Coef. | Std.Err. | t | P>t | [95%Conf. | Interval] |

| d1RES | ||||||

| L2. | -0.548 | 0.130 | -4.200 | 0.008 | -0.883 | -0.213 |

| d1REMIT | ||||||

| --. | 0.471 | 0.192 | 2.450 | 0.058 | -0.023 | 0.966 |

| L1. | 0.348 | 0.142 | 2.450 | 0.058 | -0.017 | 0.712 |

| d1ZSRE | ||||||

| --. | -0.285 | 0.106 | -2.680 | 0.044 | -0.558 | -0.012 |

| L2. | 0.556 | 0.101 | 5.500 | 0.003 | 0.296 | 0.816 |

| L4. | 0.964 | 0.145 | 6.660 | 0.001 | 0.591 | 1.336 |

| d1EDUC | ||||||

| --. | -2.361 | 0.382 | -6.190 | 0.002 | -3.343 | -1.380 |

| L1. | -3.311 | 0.445 | -7.450 | 0.001 | -4.454 | -2.168 |

| L2. | -0.988 | 0.239 | -4.130 | 0.009 | -1.603 | -0.374 |

| L3. | 0.417 | 0.181 | 2.300 | 0.070 | -0.049 | 0.884 |

| INCM | ||||||

| --. | -0.264 | 0.067 | -3.930 | 0.011 | -0.436 | -0.091 |

| FDI | -4.275 | 0.668 | -6.400 | 0.001 | -5.992 | -2.558 |

| PPP | 0.000 | 0.000 | 3.560 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| d1TO | -0.027 | 0.051 | -0.540 | 0.613 | -0.157 | 0.103 |

| _cons | 5.937 | 0.807 | 7.360 | 0.001 | 3.864 | 8.010 |

|

| D.d1RES | Coef. | Std.Err. | t | P>t | [95%Conf. Interval] | SIG | ADJ |

| d1RES | |||||||

| L1. | -1.926 | 0.303 | 6.350 | 0.001 | -2.705 | -1.146 | *** |

| LONGRUN RESULTS | |||||||

| d1REMIT | 1.584 | 0.342 | 4.630 | 0.006 | 0.704 | 2.463 | *** |

| d1ZSRE | 0.547 | 0.207 | 2.640 | 0.046 | 0.015 | 1.079 | ** |

| d1EDUC | -3.140 | 0.601 | -5.220 | 0.003 | -4.686 | -1.594 | *** |

| INCM | -0.073 | 0.030 | -2.430 | 0.059 | -0.151 | 0.004 | * |

| FDI | -2.220 | 0.507 | -4.380 | 0.007 | -3.523 | -0.917 | *** |

| PPP | 0.000 | 0.000 | 3.670 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ** |

| d1TO | -0.014 | 0.027 | -0.520 | 0.628 | -0.085 | 0.056 | |

| SHORTRUN RESULTS | |||||||

| d1RES | |||||||

| LD. | 1.105 | 0.289 | 3.820 | 0.012 | 0.361 | 1.849 | ** |

| d1REMIT | |||||||

| D1. | -2.578 | 0.502 | -5.130 | 0.004 | -3.870 | -1.287 | *** |

| LD. | -2.231 | 0.396 | -5.630 | 0.002 | -3.249 | -1.212 | *** |

| L2D. | -2.273 | 0.380 | -5.990 | 0.002 | -3.249 | -1.297 | *** |

| L3D. | -1.319 | 0.281 | -4.700 | 0.005 | -2.041 | -0.598 | *** |

| d1ZSRE | |||||||

| D1. | -1.338 | 0.299 | -4.470 | 0.007 | -2.108 | -0.568 | *** |

| LD. | -1.468 | 0.247 | -5.940 | 0.002 | -2.104 | -0.833 | *** |

| L2D. | -0.912 | 0.164 | -5.560 | 0.003 | -1.334 | -0.491 | *** |

| L3D. | -0.964 | 0.145 | -6.660 | 0.001 | -1.336 | -0.591 | *** |

| d1EDUC | |||||||

| D1. | 3.685 | 0.545 | 6.770 | 0.001 | 2.285 | 5.085 | *** |

| INCM | |||||||

| D1. | -0.123 | 0.080 | -1.540 | 0.183 | -0.327 | 0.082 | *** |

| _cons | 5.937 | 0.807 | 7.360 | 0.001 | 3.864 | 8.010 | *** |

| Test | Method used | p-value | Conclusion |

| Heteroscedasticity Test | White test | 0.4140 | No Heteroskedasticity |

| Autocorrelation Test | Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation Test | 0.4470 | No Autocorrelation |

| Normality Test | Jarque-Bera test | 0.9512 | Error term is Normally Distributed |

| Model Specification Test | Ramsey RESET Test | 0.0988 | Model Is Correctly Specified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).