1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) remains a significant public health concern, ranking as the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men in the United States. Alarmingly, the incidence rate has risen by 3% every year since 2014, underscoring the urgent need for improved understanding and management of the disease [

1]. PCa is a biologically heterogeneous disease influenced by a complex interplay of clinical and demographic risk factors, including genetic predisposition, race and ethnicity, obesity, and age. While localized PCa is often manageable with current therapeutic strategies, metastatic PCa presents a far more formidable clinical challenge, with significantly poorer prognosis and limited treatment options [

2]. Projections estimate that by 2030, nearly 192,500 men will be living with metastatic PCa, highlighting the critical need to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that drives disease progression and metastasis.

One protein of growing interest in cancer biology is the cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61), also known as CCN1 [

3]. CYR61 is a matricellular protein that plays multifaceted roles in regulating cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. As a secreted component of the extracellular matrix, CYR61 interacts with integrins and heparan sulfate proteoglycans, influencing various signaling pathways involved in tumorigenesis. Despite its established roles in other malignancies, the specific function of CYR61 in PCa remains poorly understood. Notably, CYR61 contains an insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP) domain, suggesting a potential regulatory relationship with insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1), a hormone known to promote mitogenic and anti-apoptotic effects in prostate epithelial cells [

10].

IGF1 has been implicated in the initiation and progression of PCa, with elevated circulating levels associated with resistance to various chemotherapies [

11]. Moreover, IGF1 signaling has been linked to the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), a lethal form of the disease characterized by continued androgen receptor (AR) activity despite androgen deprivation therapy [

12]. Reduced expression of the IGF1 receptor (IGF1-R) has also been proposed as a biomarker for metastatic potential, further emphasizing the clinical relevance of this pathway [

13]. However, the potential molecular interplay between CYR61 and IGF1 in PCa has not been systematically investigated. Therefore, elucidating whether CYR61 modulates or is modulated by IGF1 signaling could provide important insights into mechanisms driving metastasis and therapeutic resistance.

While not previously described in PCa, the relationship and potential targeting of the IGF1-CYR61 axis in metastatic osteosarcoma have been reported. Specifically, CYR61 triggers primary tumor vascularization via an IGF1-R-dependent epithelial to mesenchymal transition-like process [

13]. Given that approximately 70% of metastatic PCa patients harbor bone metastases [

2], these findings raise the possibility that similar molecular interactions may be at play in PCa metastasis. Thus, investigating the IGF1-CYR61 relationship in PCa is both timely and warranted.

In this study, we explore the role of CYR61 and its potential crosstalk with IGF1 in metastatic PCa using well-established cell line models, including PC3 and LNCaP, and the androgen receptor (AR)-positive 22rv1. We further examine the impact of CYR61 silencing on PCa aggressive properties of these cells. Our findings provide new insights into the molecular underpinnings of PCa progression and suggest that targeting the CYR61-IGF1 axis may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for combating metastatic disease.

3. Discussion

The connective tissue growth factor, cysteine-rich protein, and nephroblastoma overexpressed gene (CCN) family are extracellular matrix proteins with reported roles in tumor invasion [

15,

16,

17]. The CCN family of proteins is involved in different key molecular processes, including coordination in tumor microenvironments, tumorigenesis, and cancer metastasis [

18,

19,

20]. In this paper, we focused on CYR61, also known as CCN1, which has been shown to act as a tumor-promoting factor and is likely a key regulator of cancer progression [

21]. The IGF-binding protein domain of CYR61 is of particular interest because studies have reported that higher circulating levels of IGF1 are associated with metastatic disease and resistance to various chemotherapies [

11]. We focused on characterizing the effect of CYR61 and its interplay with IGF1 on metastatic PCa and potential signaling pathway mechanisms. We studied three different PCa cell lines: 1) LNCaP cells, which express prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and partially express AR during high proliferation, and whose biological behavior is most similar to the majority of newly diagnosed PCa cases [

22,

23]; 2) PC3 cells, which do not express AR or PSA, are androgen-independent [

23,

24], and exhibit highly aggressive behavior, which is consistent with the biological behavior of advanced or treatment-resistant PCa; and 3) AR-positive 22rv1. With the use of these three models—LNCaP, PC3, and 22rv1— we aimed to represent a spectrum of PCa, encompassing both androgen-dependent and castration-resistant tumors. LNCaP cells, derived from lymph node metastasis, are androgen-sensitive and represent early-stage, hormone-responsive PCa. PC3 cells, originating from bone metastasis, are androgen-independent and highly aggressive, modeling advanced, castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). 22Rv1 cells, derived from a relapsed xenograft, are androgen-independent but retain AR expression, making them a model for CRPC with active AR signaling. Our results demonstrated that CYR61 exerted pro-survival properties on PCa cells, and its expression was further induced with IGF1.

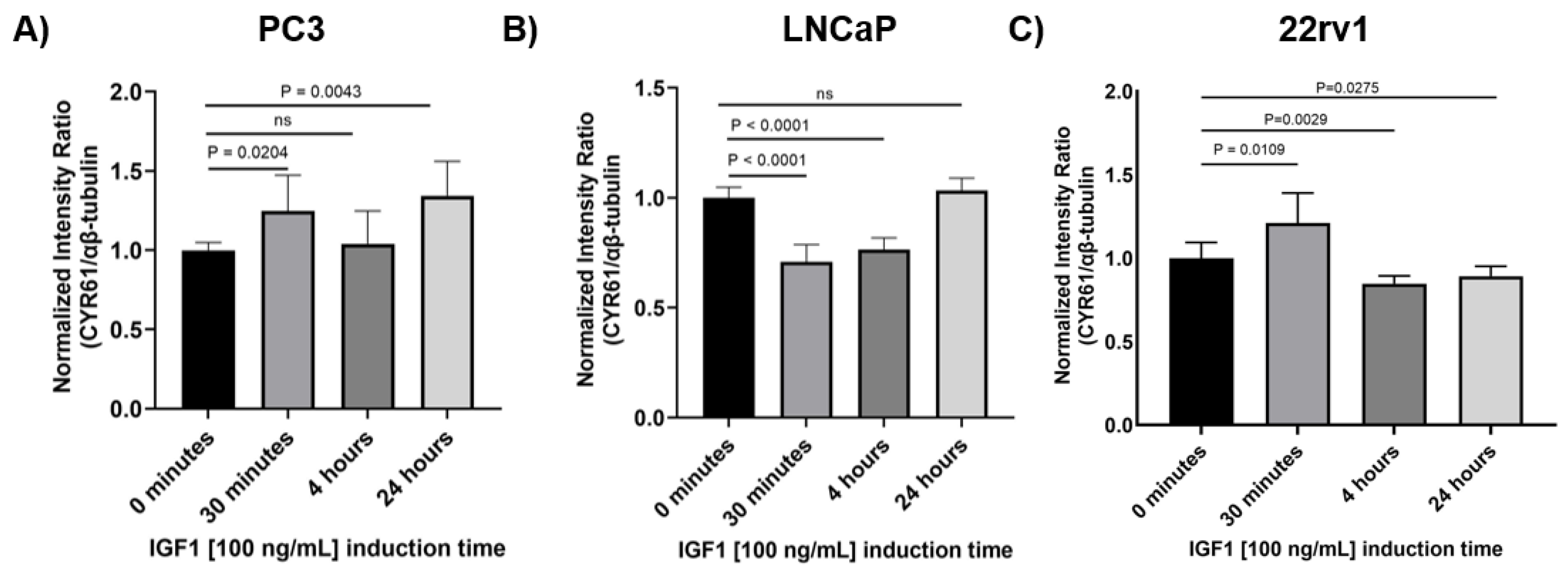

Previously, in cellular models of breast cancer, it was found that IGF1 promoted CYR61-induced cell growth and invasion [

25]. In PCa, we found that IGF1 induced a significant increase in CYR61 levels in PC3 and 22rv1 cells at the 30 min time point, and in PC3 cells again at the 24-h time point. Conversely, in LNCaP cells, IGF1 induced a significant decrease in CYR61 levels at 30 min and 4 h. Similar to what we observed in PC3 cells, Sarkissyan et al. [

25], showed that in MCF7 breast cancer cells, CYR61 is upregulated significantly after 20 min of induction, with IGF1 demonstrating increased proliferation and invasion. A possible explanation for the observed decrease in CYR61 expression in LNCaP cells is that IGF1 stimulation alters the surface expression of specific integrins, such as α5, αV, and β1, which are known to mediate CYR61 binding [

26]. In particular, a study investigating the effect of IGF1 stimulation on surface expression of the integrins α5, αV, and β1 in a panel of PCa cells [

27], found that the surface expression αV subtype is reduced in LNCaP cell lines after 24 h of IGF1 treatment. This is notable because CYR61 interacts with the cell surface primarily through the αV integrins subtype, and αV integrin’s expression is correlated with enhanced cancer cell migration in several cellular models of non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and oesophageal squamous carcinoma [

28]. In contrast, PC3 cells exhibited a marked increase in αV integrin expression following IGF1 stimulation at both 4 h and 24 h, which is consistent with our observations of increased CYR61 expression in these cells. These findings suggest that the differential regulation of αV integrin by IGF1 may underline the cell line-specific effects on CYR61 expression.

Consistently, high circulating levels of IGF1 have been positively associated with an increased risk of PCa [

11,

29]. In addition, AR has been shown to directly regulate transcription of the IGF1 receptor in PCa cells [

30]. A second possible explanation for the decrease of CYR61 in LNCaP cells is aberrant AR activation during high proliferation. Induction of these cells with recombinant human IGF1 and an increase in CYR61 expression can implicate a regulatory mechanism underlying AR expression through IGF1-mediated signaling pathways in PCa progression. Our findings suggest a potential novel interaction between AR and IGF1 signaling pathways that can contribute to PCa.

Together, our observations indicate for the first time that CYR61 expression can be induced by IGF1 in the context of PCa, showing that this protein is highly sensitive to growth factor induction. The upregulation of CYR61, which mediates cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, may result in increased metastasis. These findings are particularly significant for patients with elevated levels of circulating IGF1, who may face a higher risk of developing PCa and experiencing poorer survival outcomes. Interestingly, our results also demonstrate that CYR61 expression is rapidly upregulated in 22Rv1 PCa cells within 30 min of IGF1 stimulation, followed by a marked reduction at 4 h and 24 h post-treatment. This transient induction pattern suggests that CYR61 functions as an immediate early gene (IEG) in response to IGF1 signaling, a phenomenon commonly observed with growth factor-inducible genes that are rapidly but transiently activated to initiate downstream transcriptional programs [

31]. The early spike in CYR61 may reflect activation of the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways, both of which are downstream of the IGF1 receptor and known to modulate CYR61 transcription [

32,

33]. The subsequent decline in CYR61 expression could be attributed to negative feedback regulation, receptor desensitization, or transcriptional repression mediated by downstream effectors, including FOXO transcription factors or other inhibitory regulators that restore homeostasis [

34]. Additionally, CYR61 is known to be tightly regulated by temporal and context-specific cues, consistent with its dual role in promoting both proliferation and apoptosis depending on cellular context [

4]. This dynamic expression profile underscores the complexity of CYR61 regulation and highlights its potential role as a key mediator of IGF1-driven cellular responses in PCa.

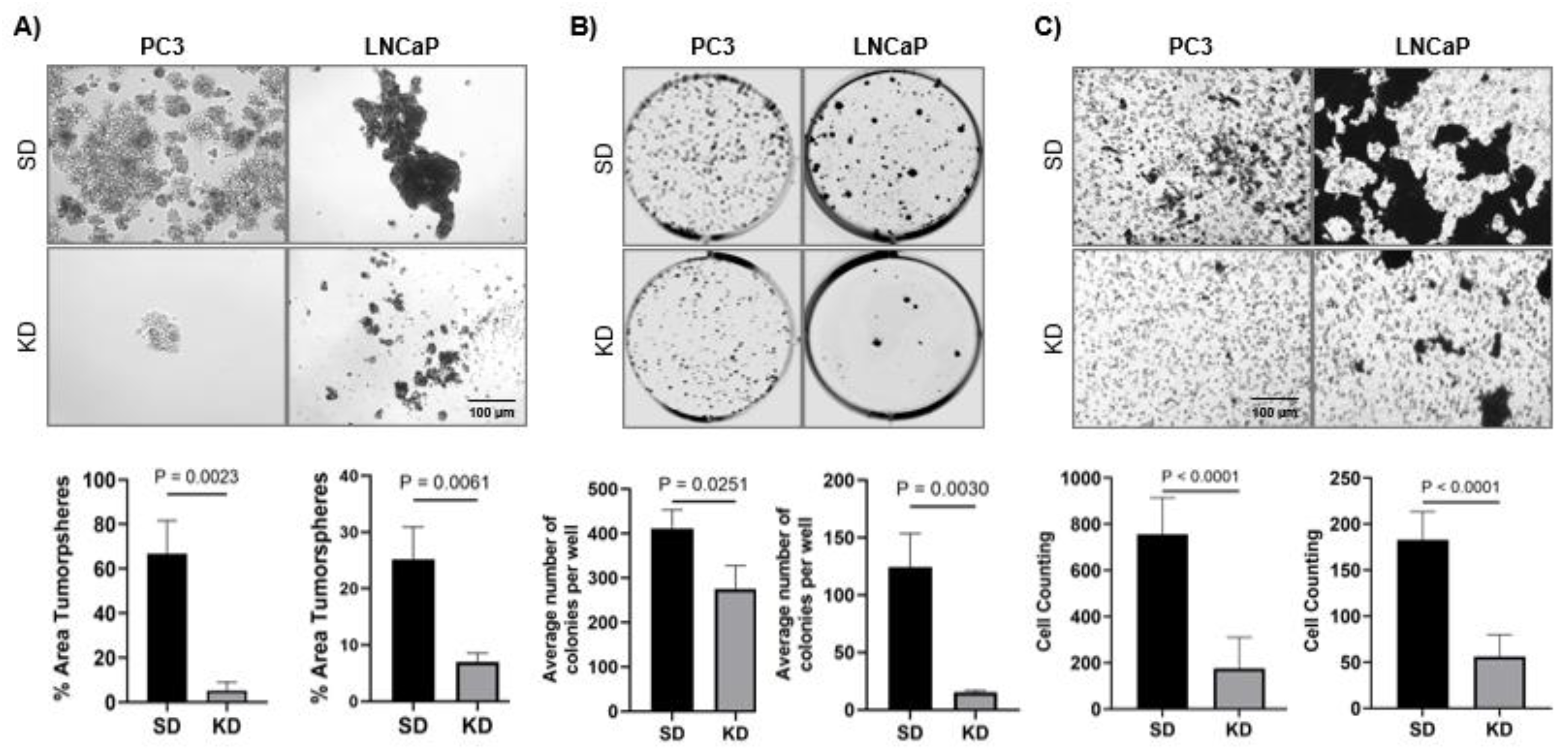

A novel aspect of our study was the investigation of the ability of CYR61 to induce stemness. For that purpose, we optimized a prostasphere assay on CYR61 KD cells. This assay serves as the standard method for assessing the self-renewal capacity of cancer-stem-like cells (CSC) in cell cultures [

35]. In addition, this assay relies on the premise that only CSCs can thrive and proliferate without anchorage in the absence of serum. Aggressive cell lines, such as PC3, in which expression of mesenchymal/stem cell molecular markers is exacerbated, CYR61 expression is elevated in comparison to other less-aggressive cell lines (

Supplementary Figure S2). In cellular models of breast cancer, it has been suggested that mesenchymal-transformed non-invasive cells, such as MCF-7, show increased invasiveness and elevated CYR61 expression [

36]. In our prostaspheres models, we show for the first time that CYR61 KD impaired the formation of these spheres in PC3 and LNCaP cells. Similarly, in models of pancreatic carcinogenesis, CYR61 silencing reversed the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, blocks the expression of stem-cell-like traits, and inhibits migration [

37].

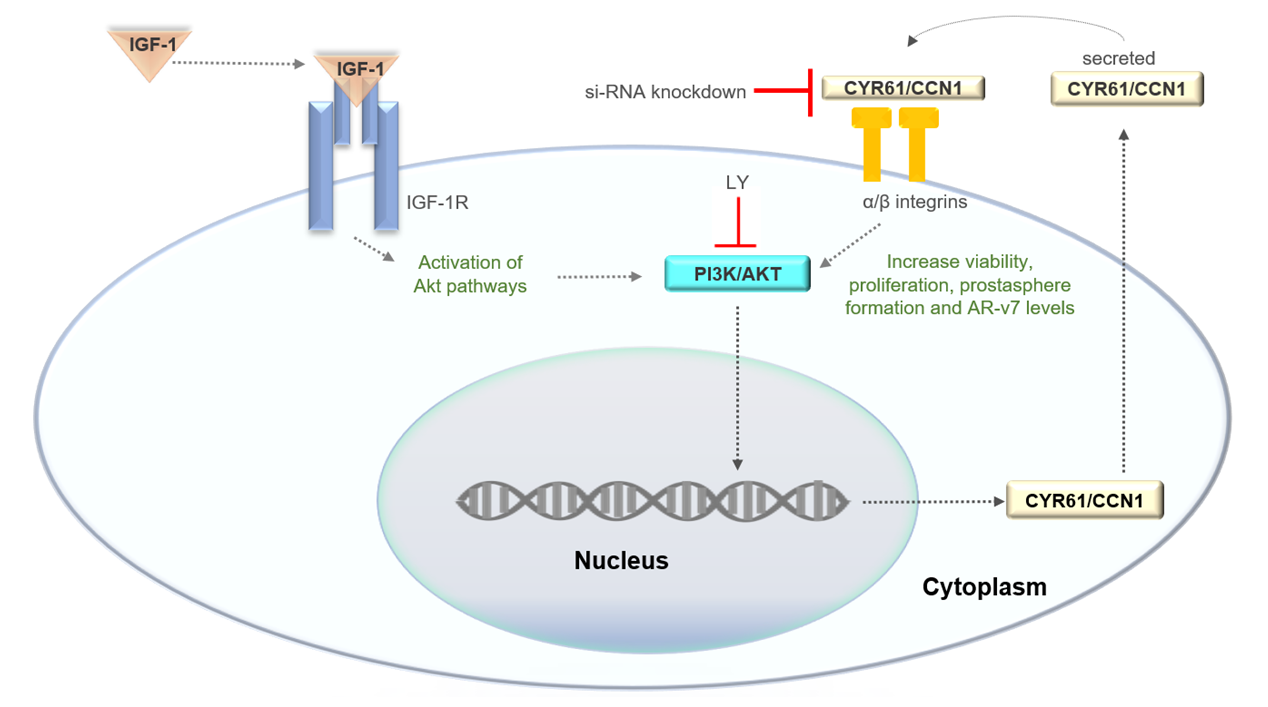

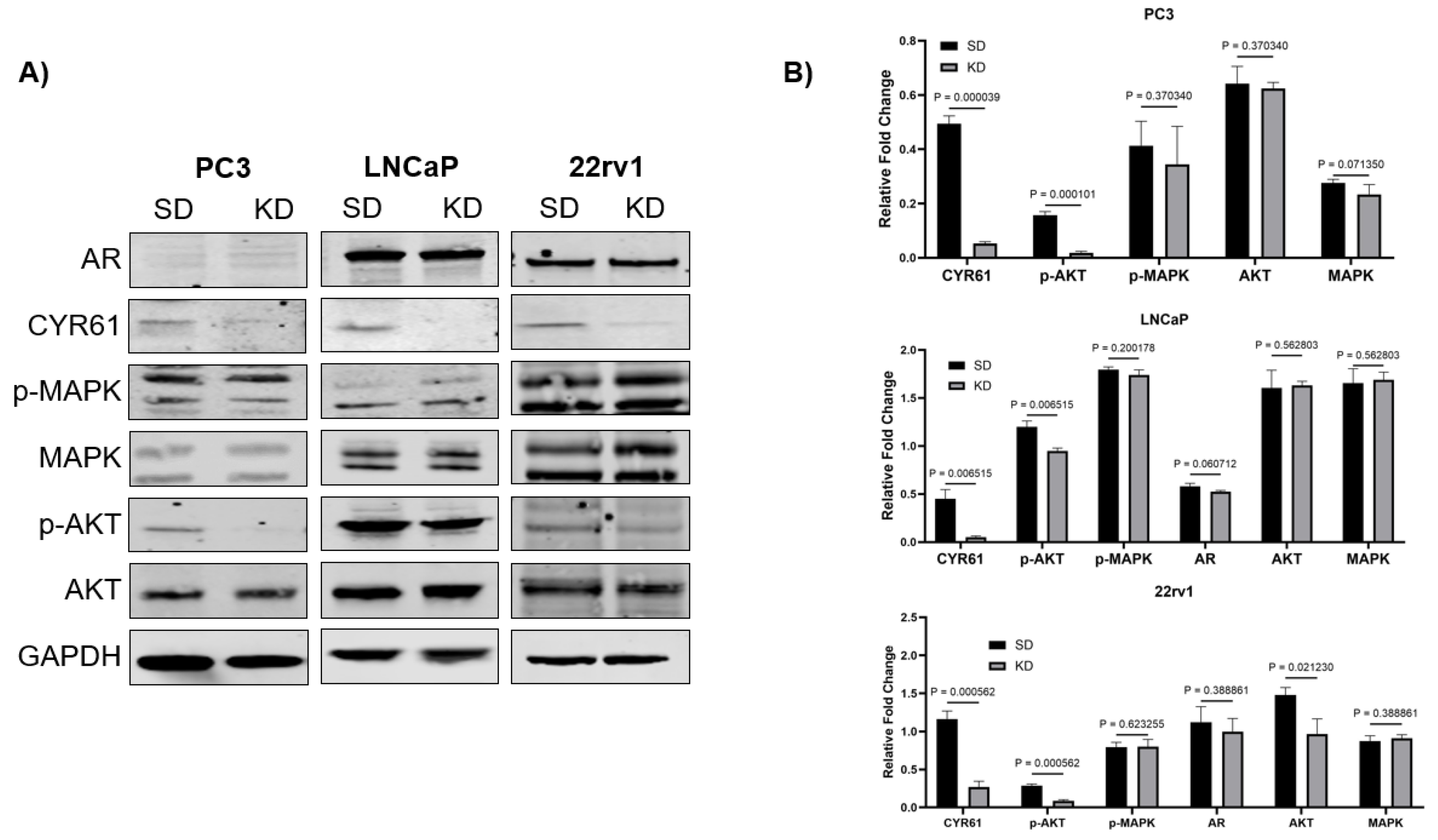

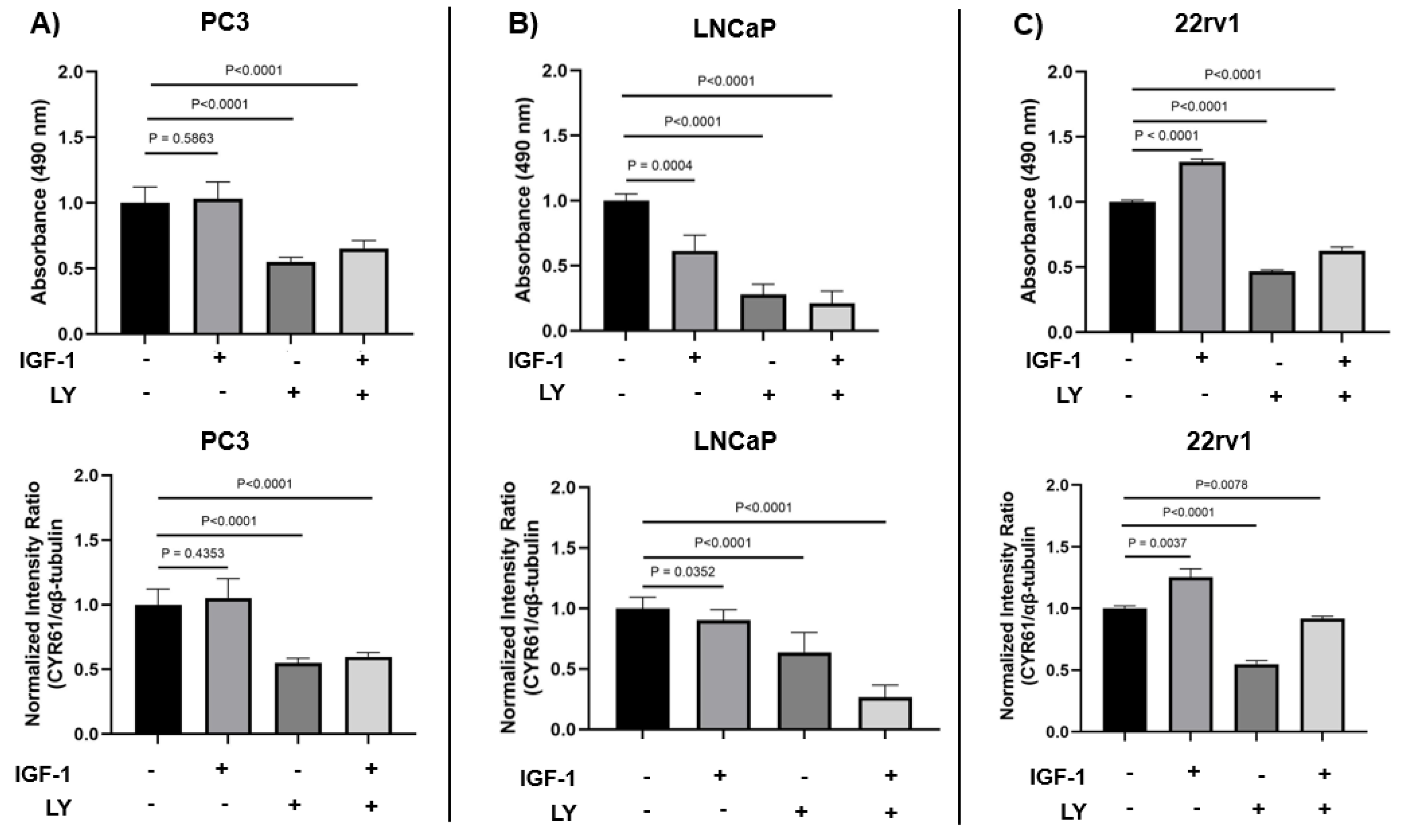

We investigated whether the CYR61 upregulation due to IGF1 induction was mediated through the PI3K/AKT pathway, which is one of the central pathways in IGF1-induced PCa growth [

38]. CYR61-KD PC3, LNCaP, and 22rv1 cells showed significant decreases in p-AKT levels, but not AKT, compared to CYR61-SD control cells. The MAPK pathway, which is the other key downstream pathway from IGF1, was also assessed [

39]. CYR61-KD PC3, LNCaP, and 22rv1 cells did not show significant changes in levels of p-MAPK or MAPK. Together, these data suggest that IGF1-mediated CYR61 expression is intrinsically mediated through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and not the MAPK signaling pathway.

The AR signaling pathway regulates PCa cell proliferation and apoptosis [

40]. An important mechanism through which PCa adapts to treatments targeting AR signaling is the constitutively active AR splice variants, especially AR-V7. The AR-V7 splice variant has been studied extensively, but its role in regulating metastatic progression of castration-resistant PCa (CRPC) remains unclear [

41]. We found that KD of CYR61 in the high proliferative LNCaP cells led to a significant reduction in AR-V7 expression, whereas in 22Rv1 cells, this effect was absent. This differential response likely reflects cell line-specific regulatory mechanisms and differences in AR signaling dynamics. LNCaP cells usually express only the full-length AR (AR-FL) and depend on ligand-activated AR signaling, making them highly sensitive to upstream regulators that affect AR gene transcription or mRNA splicing [

42,

43]. CYR61, a matricellular protein with known roles in cell signaling and gene transcription, may influence AR or AR splice variant expression through modulation of integrin signaling or downstream effectors such as PI3K/AKT or MAPK pathways, which are known to intersect with AR signaling [

4,

44]. Conversely, 22Rv1 cells inherently express high levels of AR-V7 due to intragenic rearrangements and aberrant splicing, often independently of upstream signals [

45]. This may render AR-V7 expression in 22Rv1 cells less susceptible to modulation by CYR61 KD, indicating that in this context, AR-V7 is constitutively expressed and uncoupled from extracellular matrix–mediated regulatory pathways. These results suggest that CYR61 may contribute to AR variant regulation in a context-dependent manner, potentially through effects on splicing machinery or transcriptional co-regulators in LNCaP cells, and highlight the importance of tumor heterogeneity in therapeutic targeting of AR signaling in PCa.

We found that IGF1 stimulated PCa cell proliferation and induced CYR61 expression through a PI3K/AKT-dependent mechanism, although the degree of response varied by cell line. The intermediate androgen-responsive 22Rv1 cells exhibited clear IGF1-dependent increases in proliferation and CYR61 expression, both of which were effectively blocked by PI3K inhibition. This suggests that IGF1 signaling through PI3K/AKT is critical in these contexts. Interestingly, in androgen-independent PC3 cells, IGF1 alone did not significantly impact proliferation or CYR61 expression, but LY treatment markedly reduced both, suggesting that constitutive PI3K/AKT activity may be maintaining basal levels of proliferation and CYR61 in the absence of exogenous IGF1. These findings highlight CYR61 as a downstream effector of PI3K/AKT signaling in PCa and suggest its potential as a biomarker or therapeutic target, particularly in tumors responsive to IGF1 signaling.

Our findings implicating IGF1 induction in CYR61 upregulation suggest important translational applications, particularly for understanding PCa risk across different populations [

46]. Pooled analyses examining the associations of anthropometric, behavioral, and sociodemographic factors with circulating concentrations of IGF1 in 16,024 men from 22 studies report that Hispanic/Latino (H/L) men with PCa tend to have lower circulating levels of IGF1 and its binding proteins, which may reduce the amount of bioavailable IGF1. Despite this, high serum levels of IGF1 in some H/L men are still associated with increased PCa risk. In addition, low IGF1-R expression in this group was linked to a higher likelihood of metastatic disease [

11]. Among African-American men, specific genetic variants in IGF1 are associated with increased PCa risk [

47]. Furthermore, circulating levels of IGF1 are known to be heritable, influenced by factors such as vitamin D, and have been linked to resistance to various chemotherapies [

48,

49]. These findings highlight how racial and ethnic differences in IGF signaling may contribute to disparities in PCa disease and progression. Consequently, increased IGF1-induced CYR61 activity, potentially acting through the classical PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, may represent a mechanism by which tumors evolve into more aggressive and invasive phenotypes. Further studies are needed to validate these observations and to explore whether targeting CYR61 could serve as a therapeutic strategy for advanced PCa.

A limitation in our study is the use of three PCa cell lines. Although representative of androgen-dependent and castration-resistant tumors, the use of PC3, LNCaP and 22rv1 cell lines may not reflect the full heterogeneity of PCa seen in patients and may not fully capture the complexity of PCa progression in vivo. Cell lines have inherent limitations, such as differences in genetic background and cellular behavior that may not accurately mimic the tumor microenvironment or the molecular interactions within a living organism. Therefore, while the findings provide valuable mechanistic insights, further research is needed to explore these additional pathways and validate the results in more complex and clinically relevant models.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines

PCa cell lines, PC3, LNCaP and 22rv1, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA, Cat# CRL-1435, CRL-1740, and CRL-2505, respectively) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Corning, Corning, NY, USA Cat# 10-040-CM), supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning, Corning, Cat# MT35010CV), penicillin/streptomycin (Corning, Cat# 30-002-CI), and normocin 1G (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA, Cat# NC9390718). Cells grew under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Short tandem repeat service provided by ATCC (Cat# ATCC-135-XV) was used to authenticate the cell lines. Mycoplasma testing was conducted at least twice a year using the Lonza MycoAlertTM Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland, Cat# LT07-218).

PC3 cells are androgen-independent and lack endogenous AR expression, representing an advanced, castration-resistant phenotype. In contrast, LNCaP cells are androgen-sensitive and express functional AR, making them a model for hormone-responsive PCa. 22Rv1 cells express both full-length AR and constitutively active AR splice variants, such as AR-V7, and are used to model castration-resistant PCa with partial AR signaling activity.

4.2. Antibodies

Rabbit antibodies targeting the following proteins were acquired from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA): CYR61 (D4H5D) (Cat# 14479S), α/β-tubulin (Cat# 2148S), β-actin (13E5) (Cat# 4970), Phospho-AKT (Thr308) (Cat# 2965), Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Cat# 9101S), Androgen Receptor (D6F11) (Cat #5153). Mouse monoclonal antibodies included CYR61 (A-10) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA, Cat# sc-374129).

4.3. Immunoblotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared by lysing the cell pellet in 100 µL Invitrogen™ Cell Lysis Buffer II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA Cat # FNN0021) on ice for 30 min, vortexing at 10 min intervals. The cell lysis buffer was supplemented with 1 mM Thermo Scientific™ PMSF Protease Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# PI36978) and Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# P178440). The cell extract was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentration of the lysates was determined using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 23225) to ensure equal loading of proteins separated on individual lanes by SDS-PAGE (NuPAGE 4–12%, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples for immunoblot analysis were diluted in ultrapure water, Invitrogen™ 1× Bolt™ Sample Reducing Agent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# B0004), and Invitrogen™ NuPAGE™ Lithium Dodecyl Sulfate Sample Buffer (1×) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# NP0007) to a concentration of 50 µg of protein per 20 µL, then heated at 70 °C for 10 min. Electrophoresis was followed by protein transfer to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Millipore Sigma, Burlington MA, USA, Cat# IPFL00010). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with Intercept® Blocking Buffer (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA Cat# 927-60001) and probed overnight with appropriate primary antibodies. Membranes were then washed with TBS-Tween buffer (20 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.6, 140 mM NaCl, and 0.2% Tween 20) three times for 5 min each. After washing, membranes were incubated with IRDye® 680RD Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Secondary Antibody (Licor, Cat# 926-68071) or IRDye® 680RD Goat anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody (Licor, Cat# 926-68070). Washes were repeated after secondary antibody incubation. Membranes were imaged using a Li-Cor Odyssey scanner. Protein bands from at least 3 independent blots were scanned for each protein of interest, quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, Fiji Version 1.44a), and normalized to α/β-tubulin or β-actin loading control protein bands to determine fold upregulation.

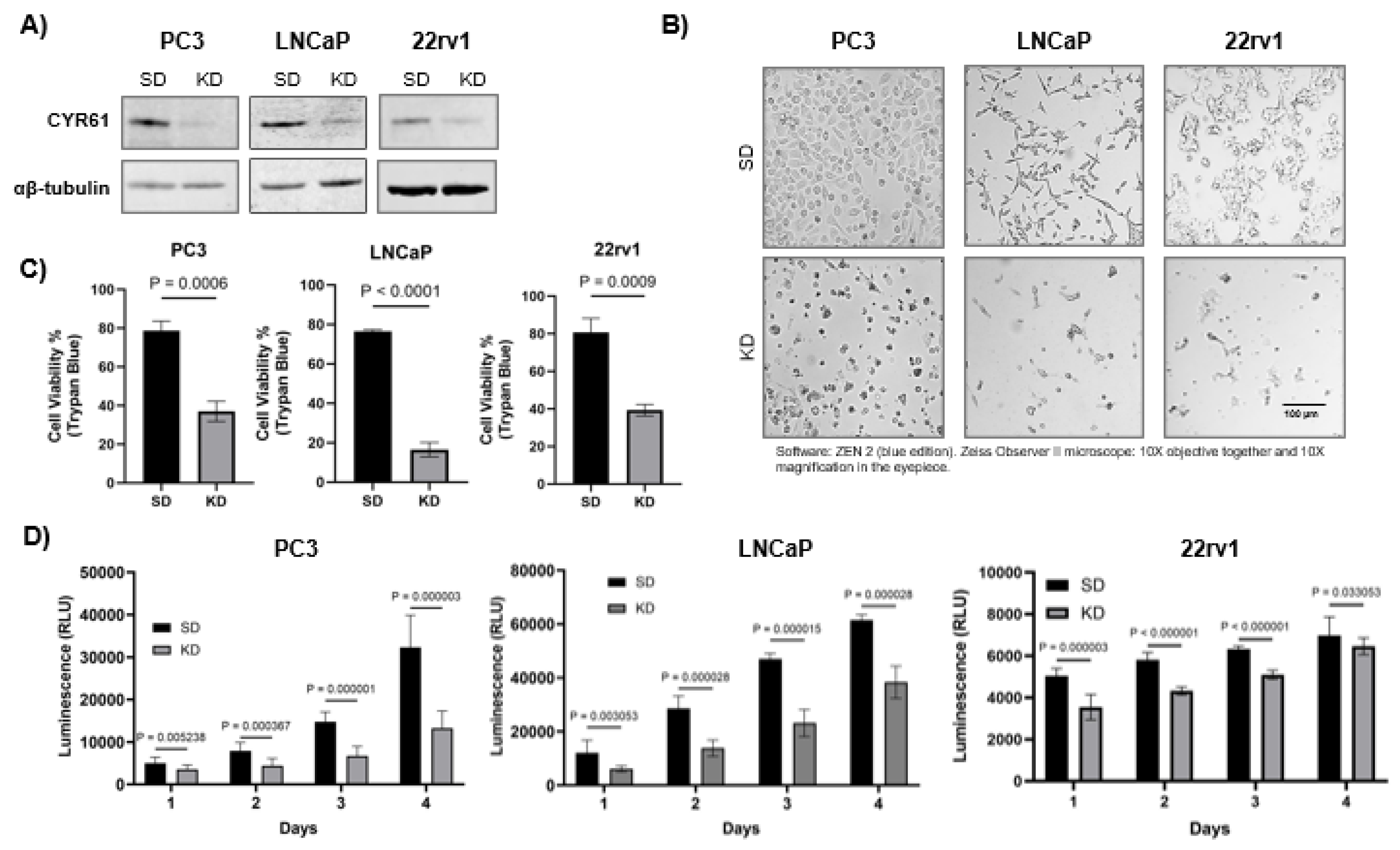

4.4. Cell Viability Assay

Trypan blue dye exclusion assay was employed to assess the effects of CYR61 small interference (siRNA) on the viability of PC3, LNCaP, and 22rv1 cells. Following siRNA transfection, cells (both floating and adherent) were collected, pelleted by centrifuging at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and resuspended in 1 mL 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After pellet resuspension, 10 µL of cell suspension was combined with 10 µL trypan blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# MT25900CI), and live cells were counted using a Cellometer Vision CBA Image Cytometer (Nexcelom, San Diego, CA, USA). Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the viability of the scrambled siRNA duplex (SD) control.

The CellTiter-Glo® assay was used to assess cellular proliferation and viability. Following CYR61 siRNA transfection, PC3, LNCaP and 22rv1 cells were seeded (5000 cells/well) in opaque-walled 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 12-566-620) and 100 µL complete media. Control wells containing medium without cells were used to determine background luminescence. Cells were assessed for 1 to 4 days post-transfection. After each time point, a volume of CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 Reagent equal to the volume of cell culture medium present in each well (100µl) was mixed for 2 min on an orbital shaker to induce cell lysis. Following this, the plate was incubated at room temperature for 10 min to stabilize the luminescent signal. The luminescence was recorded using an integration time of 0.25–1 sec per well per manufacturer’s instructions.

4.5. RNA Interference

PC3, LNCaP and 22rv1 cells (50,000 cells per well) were cultured on 6-well plates and transfected after 24 h with either 50 nM or 100 nM siRNA for up to 96 h. The siRNA sequences used were as follows: si-CYR61 knockdown (KD, pool of three different siRNA duplexes from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-39331). Cells were transfected using Interferin® siRNA transfection reagent (Polyplus-transfection®, Illkirch, France, Cat# 409-01). Scrambled siRNA duplex (SD, Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA, Cat# D-001210-0105) was used as a non-targeting negative control. Protein depletion was assessed by immunoblotting.

4.6. Clonogenic Assay

PC3, LNCaP and 22rv1 cells were transfected with CYR61 siRNA and grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS for 72 h. Next, an equal number of viable transfected cells was transferred to 6-well culture plates (500 cells/well for PC3 and 1000 cells/well for LNCaP and 22rv1). Colony formation plates were incubated for 10 d at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. Adherent colonies were washed with 1× PBS, fixed with 3:1 (v/v) methanol:acetic acid solution for 5 min, washed again with 1× PBS, stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 20 min, and then washed gently with tap water. Images of the stained colonies were acquired using a Li-Cor Odyssey scanner, and quantification was performed using the automated colony counting capability of Image J software following identical parameters for each well.

4.7. Prostasphere Formation Assay

Spheroid cultures from siRNA transfected cells were maintained using complete MammoCult™ medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada, Cat# 05620) supplemented with hydrocortisone (0.48 g/mL, Millipore Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# H0135), heparin (4 g/mL Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat# H3149), and 1% penicillin/ streptomycin. PC3 and LNCaP cells were seeded at 50,000 cells per well and transfected with the various siRNAs. After 48 h, an equal number of viable cells (1000 cells/well) were harvested and resuspended 50 times in MammoCult™ medium to ensure a single-cell suspension. Cells then were seeded in untreated 24-well plates (Genesee Scientific, Morrisville, NC, Cat# 25–102) with 0.5 mL MammoCult™ medium. Prostaspheres were grown for 10 d at 37 °C/5% CO2 and visualized in a Zeiss Observer II microscope. The prostasphere area was quantified from three independent images per individual treatment using Image J software.

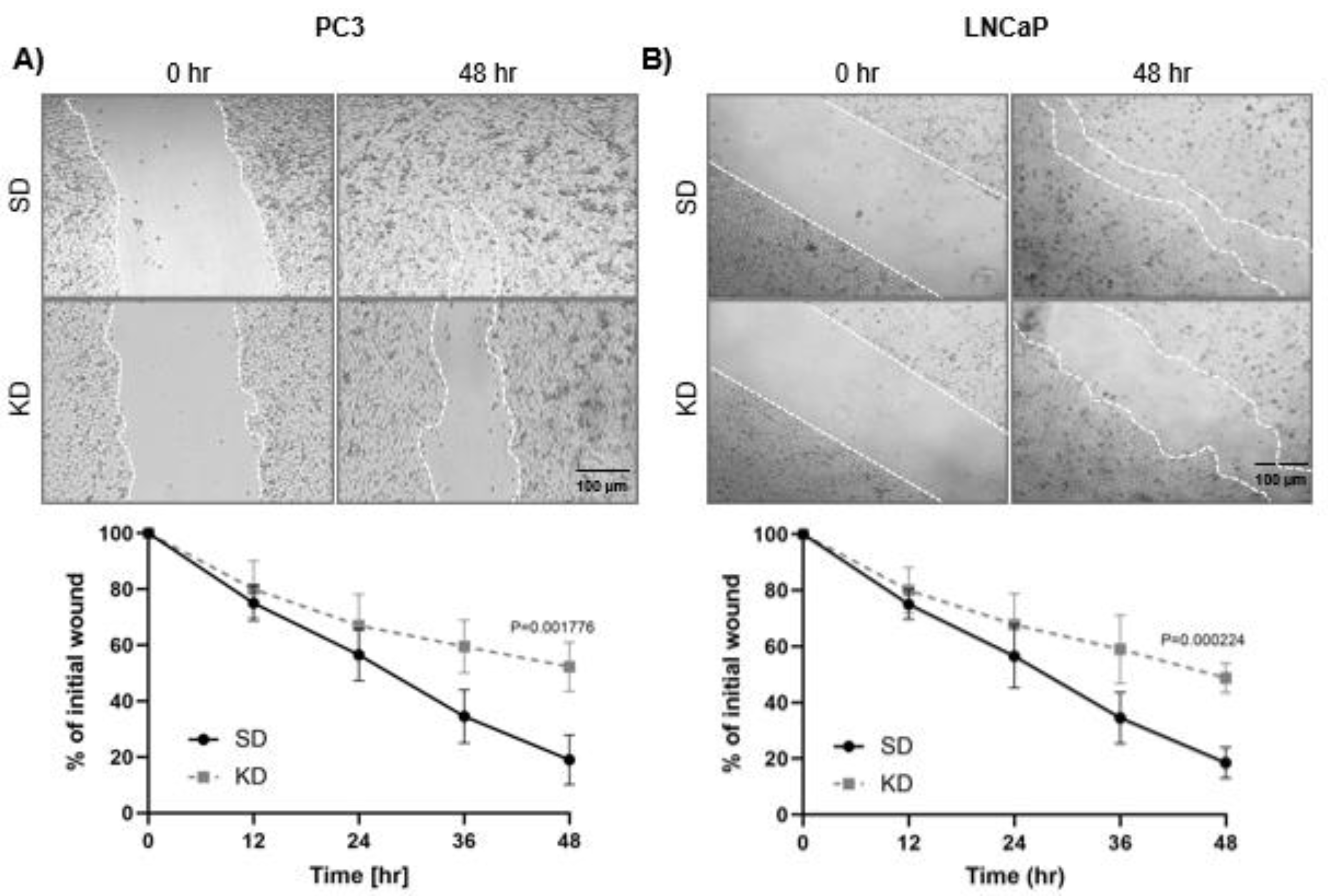

4.8. Wound Healing Assay

PC3 and LNCaP cells were examined for their mobility using a wound-healing assay. Following CYR61 siRNA transfection for 72 h, cells were collected and seeded into a 24-well plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 09-761-146) to reach semi-confluency. Confluent transfected cells were “scratch wounded” with a P200 pipette tip. Wound closure was monitored by a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope. Over a 48 h time period, images were taken every 12 h and analyzed with ImageJ software. The average wound area relative to the initial wounding (0 h) was determined in three independent triplicate assays and compared to control cells transfected with SD negative control.

4.9. IGF1 Induction Treatment

To determine if IGF1 increased the expression of CYR61, PC3, LNCaP and 22rv1 cells were induced with 100 ng/ml recombinant human IGF1 (Peprotech, Cranbury, NJ USA Cat# 100-11) for 30 min, 4 h, and 24 h. CYR61 protein expression levels were measured at different time points. Experimental cells were plated, and once 70% confluent, they were switched to serum-free media with 0.1% BSA for overnight starvation. Immediately after exposure to IGF1 for the designated time, the cells were collected for protein extraction or evaluated for expression.

4.10. In-Cell Western (ICW) Assay

The ICW assay was performed using the Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PC3, LNCaP and 22rv1 cells were grown in 96-well plates until they reached 60–70% confluency and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at selected time intervals post-transfection or IGF1 induction for the ICW assay. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature and blocked with LI-COR Odyssey Blocking Solution (LI-COR Biosciences) for 30 min. The cells were incubated at 4 °C overnight with appropriate primary antibodies. After three washes with 1× PBS, cells were stained with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h and washed twice again with 1x PBS. The plates were scanned with the Odyssey CLx Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences), and the integrated fluorescence intensities representing the protein expression levels were acquired using the software provided with the imager station (Empiria Studio 2.3, LI-COR Biosciences). The relative amount of protein was obtained by normalizing to endogenous β-actin or α/β-tubulin in all experiments.

4.11. Transwell Migration Assay

Cell migration was assessed using 24-well ThinCert™ (Greiner Bio One, Frickenhausen, Germany, Cat# 662638) permeable inserts containing PET capillary pore membranes with 8.36 mm inner diameter, 10.34 mm outer diameter, 16.22 mm height, and 8 μm pore size. The assay was carried out once the transfection time ended. PC3 and LNCaP cells were trypsinized, and 1 × 105 live cells/ml were resuspended in serum-free RPMI medium. While the cell suspensions were prepared, 500 μl of the chemoattractant (RPMI supplemented with 10 % FBS) was dispensed into each well of the 24-well ThinCert™ plates and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The ThinCert™ inserts were placed in the wells containing pre-warmed chemoattractant, and 1 × 105 live cells/ml (200 μl from the cell suspension) were added to the insert. Subsequently, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The medium in the inserts was then removed, and the membranes were washed twice in PBS. The PC3 and LNCaP cells that remained in the upper part of the insert were removed carefully with a PBS-soaked cotton swab. The cells that migrated or invaded towards the lower part of the chamber were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. The fixed cells were visualized on a Zeiss Observer II microscope and photographed. The total number of cells that migrated or invaded was counted manually using ImageJ software.

4.12. PI3K/AKT Inhibitor Induction Treatments

LY294002 (LY), 50 mM (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; Cat# 9901), which is a PI3/AKT inhibitor, was used to determine its specific role in response to IGF1-mediated CYR61 upregulation. All conditions that had a combination of IGF1 and LY were pretreated with the inhibitor 1 h before the addition of IGF1 for 24 h. The IGF1/LY-induced changes in CYR61 expression levels were assessed using the ICW assay. Cell proliferation was assessed using the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from a minimum of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Two-sample comparisons were determined using the two-tailed Student t-test. For multiple groups, we used two-way ANOVA. The p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.